Abstract

As college costs rise in the United States, many parents are forced to make difficult decisions about how to pay for their children’s higher education. Stress and conflict accompany financial issues and play a role in the financial picture for many families. Using Hill’s (Hill, Social casework 39:139–150, 1958) ABC-X model of family stress as a framework, this study describes results of a national survey of parents contributing to student loan payments for their child’s education and explores how this experience may play a role in familial conflict. Findings suggest marked gender differences in the relationship between contribution reason and the experience of conflict. Results also carry implications for financial professionals, suggesting a need for family-focused and gender-conscious financial education both before and during the student loan repayment process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Student loan borrowers in the United States owe over $1.5 trillion in outstanding student loan debt (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2019). With students unable to meet rising college costs, a growing portion of this debt is owed by parents who are repaying loans for a loved one’s higher education (Houle, 2014; Walsemann & Ailshire, 2016). Paying for children’s college education has traditionally been viewed as a transformative asset from parent to child (Gicheva & Thompson, 2015), although the specific reasons parents choose to contribute vary, ranging from a sense of obligation, to a strategic exchange for power or services, to an altruistic desire to help their children (MacDonald & Koh, 2003; Steelman & Powell, 1991). While for some parents, preparing for adult children’s college costs may take the form of regular saving towards a college fund, many cannot afford to do so, or intend to utilize scholarships or loans from the start (Price, 2015). Further, federal loan options such as PLUS loans provide the temptation of easy to acquire financial assistance geared toward parents (Wang et al., 2012). Research shows, however, that repaying student loans for children can affect parents’ personal, professional, and financial goals (Cha et al., 2005; Danziger & Ratner, 2010; Miller, 2019).

Prior research has identified a link between financial stress and conflict within family relationships, suggesting that the experience of carrying and managing different types of debt can lead to conflict and strained relationships (Masarik & Conger, 2017). Thus, it is important to identify the predictors and protective factors of financial conflict within families to mitigate negative outcomes within family relationships. To date, the effects of student loan debt on the experience of family conflict remain unknown. Moreover, no research has specifically explored mothers’ and fathers’ experiences accruing and repaying student loans for children. Building on previous research and gaps in the literature, this study uses Hill’s (1958) ABC-X model of family stress to explore how mothers and fathers experience loan repayment for their children’s education, with a focus on protective resources and perceptions related to the loans that contribute to the experience of family conflict. Following quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis further explores the themes of reported family conflict, deconstructing the nature of marital conflict between parents, as well as parent–child conflict. Finally, implications for financial professionals are discussed.

Literature Review

Gender and Financial Issues

Prior research about gender and finances more generally suggests that men and women in the same household may perceive and experience financial matters differently (Atwood, 2012; Zagorsky, 2003). Notably, the negative impacts of financial strain may be augmented for women in particular (Dunn & Mirzaie, 2012; Thorne, 2010). In a study of individuals experiencing bankruptcy, Thorne (2010) found that, for women, bankruptcy was associated with psychological harm, though men in the study did also express negative sentiments to some extent. Similarly, in Dunn and Mirzaie’s (2012) investigation of debt and psychological effects, women reported higher levels of stress. However, Almeida and Kessler (1998), found in their study of daily stressors among married couples that husbands in their sample experienced more distress regarding financial issues, although wives experienced more distress overall. As one of the few studies exploring gender differences in experiences with student loan debt specifically, findings from an investigation of Canadian borrowers with bachelor’s degrees revealed that, when controlling for other factors such as field of study, female students perceived repayment to be more difficult than male students (Schwartz & Finnie, 2002).

In addition to differing perceptions of financial stressors, another possible explanation for women experiencing greater psychological strain with financial issues may stem from gender differences in education regarding financial matters. Previous research points to gender-based disparities in financial literacy and knowledge (De Clercq & Venter, 2009; Gerrans et al., 2014). Specifically, women have demonstrated lower levels of financial literacy compared to men across multiple studies (Chen & Volpe, 2002; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2008; Taft et al., 2013). However, several researchers propose that this gender gap reflects socialized gender stereotypes, or a lack of formal financial education or financial decision-making opportunities, rather than inherent differences in capabilities (Driva et al. 2016; Fonseca et al. 2012; Goldsmith & Goldsmith, 2006).

The disparity in financial knowledge may translate to greater conflict for women, as prior research has identified financial knowledge to be a protective factor of crisis in the case of financial issues (Goff & Smith, 2005; Steen & MacKenzie, 2013). In addition to unequal levels of financial knowledge, research suggests that the impact of acquiring financial knowledge may be distinct for men and women. In a study of 5329 high school students, the positive outcomes of a financial education program differed for men and women. While men in the sample “reported achieving their financial goals to a statistically greater level than did female students” (p. 56), women demonstrated greater improvements in several areas including financial communication within their families (Danes & Haberman, 2007, p. 56).

Family Financial Conflict

Spousal Conflict

A good deal of research has established the link between financial issues and conflict among spouses. Findings from a study of married couples between ages 18–45 revealed that consumer debt was positively associated with spousal financial conflict (Dew & Stewart, 2012). Gudmunson et al. (2007) also investigated this link between money issues and spousal conflict among a sample of 4997 married couples, for whom significant correlations were demonstrated between levels of financial strain and disagreements among couples. In addition to financial difficulties, other factors have been shown to play a role in the occurrence of spousal financial conflict as well. Using a sample of 1371 married women, Britt et al. (2010) also found that while a lack of financial resources was certainly a predictor of marital financial conflict, general arguments were the strongest predictor.

Financial conflict tends to present negative outcomes for spouses. Through an assessment of diary reports by husbands and wives, Papp et al. (2009) found that while finances were not the most common topic of spousal conflict, “conflicts dealing with money were longer, especially recurrent, and held higher present and long‐term significance to partners’ relationships than other conflicts” (p. 99). Further, in a national longitudinal survey, Dew (2011) found a positive relationship between consumer debt and divorce, such that husbands and wives with debt may experience more financial conflict, and in turn, may be more likely to experience divorce. In alignment with this study, Grable et al. (2007) found that among a sample of 361 Midwestern participants, those with greater financial satisfaction were significantly less likely to have recently thought about divorce.

Parent–Child Conflict

Prior research suggests that such spousal conflict may not remain isolated within the mother-father relationship, but rather, this tension may lead to issues within parent–child relationships as well. Findings from a diary study of mothers and fathers revealed a relationship between marital conflict and parent–child conflict, such that tension between mothers and fathers was associated with subsequent tension between parent and child, a concept known as “spillover.” Gender differences arose as well, with mothers experiencing more frequent parent–child conflict than fathers (Almeida et al., 1999).

While minimal research has focused on parent–child financial conflict specifically, several studies have identified money as a source of conflict within parent–child relationships. Data from the Longitudinal Study of Generations revealed several distinct types of conflict between parents and their adult children. Among parents’ reports, parent–child conflict most often related to “differences over personal habits and lifestyle choices,” which consisted of issues such as how children spend money, “followed by concerns about communication and interaction” (Clarke et al., 1999, p. 263). Barber and Delfabbro (2000), in a telephone study of parents and adolescent children, found that parents reported money issues as the second most common source of parent–child conflict, after household chores. While focusing on younger children, a survey including 1000 parents and 881 children between ages eight and 14 revealed money as source of parent–child conflict as well. When asked how often they argue with their children about money, 22% of parents said they do so “occasionally” or “frequently” (Price, 2015).

Family Stress Theory

Family Stress Theory posits that economic stress can negatively impact family relationships, as well as the psyche and wellbeing of both parents and children (Masarik & Conger, 2017; Newland et al., 2013; Yoder & Hoyt, 2005). A critical component of Family Stress Theory is the ABC-X model (Hill, 1958), which highlights four primary components contributing to a family’s experience of crisis. The A component represents the stressor itself, B represents the family’s protective resources or supports, C represents the family’s interpretation of the situation, and finally, X represents the crisis or family outcome, resulting from interactions of all previously stated components of the model (Britt et al., 2016; Steen & MacKenzie, 2013). Thus, the ABC-X model suggests that families are not merely victim to direct effects of a stressor, but rather, the combination of families’ protective resources and interpretations of the stressor also play a critical role in influencing their experiences and family outcomes. In the presence of a stressor, strong protective resources or positive perceptions of the stressor have the potential to decrease the likelihood of crisis, while negative perceptions of the stressor or a lack of protective resources have the potential to increase the likelihood of crisis. Although outcomes of accruing and repaying student loans may be complex in this way, prior literature suggests that the impact for mothers and fathers may be distinct.

Theoretical Application

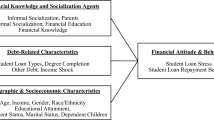

A significant body of research has demonstrated the applicability of the ABC-X model to issues of financial stress (Asebedo & Wilmarth, 2017; Britt et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2017; Steen & MacKenzie, 2013). The ABC-X model was deployed in the current study to organize and explore various factors influencing the experience of family conflict with respect to student loans, specifically spousal conflict and parent–child conflict. To account for and explore gender differences in the predictors and experiences of student loan debt, gender interaction terms were tested. In assessing the model through both quantitative and qualitative analysis, the following components were explored:

A: Repayment of student of loans for a child’s education was identified as the stressor.

B: Family resources explored in the quantitative portion of this study included income, prior student loan literacy and clarity about loan repayment. Additional protective resources are identified and assessed for spousal conflict and parent–child conflict through the qualitative section of the paper.

C: Mothers’ and fathers’ interpretations of the stressor were captured through inclusion of parents’ reasoning for taking out the loans. Further insights into mothers’ and fathers’ interpretations are explored through the qualitative section of the paper.

X: Mothers’ and fathers’ reported occurrence of family conflict was the outcome variable, representing family crisis. Qualitative analysis deconstructs this variable further, identifying two distinct types of conflict: parent–child conflict, and spousal conflict.

Based on prior research and structured around the ABC-X model, we hypothesized that (1) protective resources and interpretations of the stressor would moderate the relationship between total principal loan amount and the experience of family conflict about the loans; (2) gender would interact with protective resources and interpretations of the stressor in predicting family conflict about the loans; (3) higher levels of component B’s protective resources—income, prior student loan literacy, and loan repayment clarity—would each be negatively associated with family conflict; and (4) parents who took on loans for children out of obligation—a negative interpretation—would report more family conflict, while those who contributed out of a desire to help—a positive interpretation—would report less family conflict, as captured in component C.

Methodology

Study Design

The MIT AgeLab conducted a study of student loan borrowing in the context of family dynamics and longevity planning. The study utilized a sequential exploratory mixed-methods design with a series of focus groups followed by a national survey. The current study utilizes data solely from the national survey, consisting of both multiple-choice, and open-ended responses. Participants were recruited by Qualtrics, and the survey (N = 1874) was administered via the Qualtrics online survey platform between February 27, 2019 and April 16, 2019. The study was reviewed by The Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Protocol 674923).

Variables

Sociodemographic and Control Variables

Gender, age, race/ethnicity, current marital status, and number of children were included as sociodemographic and control variables. Age was included as a continuous variable, calculated from participant birth date and the date of survey completion. Gender (male = 0, female = 1), race/ethnicity (non-White = 0, White = 1), current marital status (not married = 0, married = 1), and number of children (one child = 0, more than one child = 1) were recoded and included as binary variables.

A: Total Principal Loan Amount

In order to account for differences in conflict due to variability in debt burden, total principal loan amount was measured using the survey question “Thinking about all the student loans for which you make payments, what was the approximate total principal student loan debt balance?” Total principal loan amount was treated as a continuous variable, and response options were recoded onto a 0–1 scale (0 = less than $50,000; 0.25 = $50,000–$99,999; 0.5 = $100,000–$149,999; 0.75 = $150,000–$199,999; and 1 = $200,000 or more).

B: Income, Prior Student Loan Literacy, and Clarity

Household income level was included as a key measure of family resources. Participants were asked, “What is your total annual household income before taxes?” Income was treated as continuous variable, and response options were recoded on a 0–1 scale (0 = $50,000–$99,999; 0.33 = $100,000–$149,999; 0.66 = $150,000–$199,999; and 1 = $200,000 or more).

Prior student loan literacy—participants’ perceived knowledge about the loans prior to their accrual—was included in place of a measure of general financial literacy. Anderson et al. (2018) suggest that discrepancies may exist between borrowers’ general financial literacy and loan literacy, as the “Big Three” financial literacy scale developed by Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) does not specifically capture an understanding for the mechanisms of student loans. Further, respondents were asked to recall their student loan literacy prior to accrual to capture how knowledge may play into the decision-making process. Prior student loan literacy was measured using the survey question “Before you took out student loans or started to make any student loan payments, how knowledgeable were you about the student loans in general (e.g., how to take out student loans, student loan interest rates, types of student loans, repayment plans, etc.)?” A 5-point Likert scale (with options ranging from not at all knowledgeable to extremely knowledgeable) was used. Prior student loan literacy was treated as a continuous variable, and answers were re-coded on a 0–1 scale (0 = not at all knowledgeable, 0.25 = slightly knowledgeable, 0.50 = moderately knowledgeable, 0.75 = very knowledgeable, and 1 = extremely knowledgeable).

As an additional dimension of knowledge about the student loans at the time of accrual, participants were asked about clarity regarding the loan repayment plan with the question, “Was it clear from the beginning that you would ultimately be contributing what you are now to the loans for your child/grandchild’s education?” Answers were coded as 0 representing no and 1 representing yes.

C: Initial Loan Contribution Reason

As a measure of mothers’ and fathers’ initial perceptions of the student loans, initial loan contribution reasons were included in analysis. Participants were asked, “Initially, why did you decide to contribute to student loan payments for your child/grandchild’s education? Select all that apply.” Among the nine total response options, the top positive and negative responses were included in analysis as dummy variables: “Desire to help” (0 = did not contribute out of a desire to help, 1 = did contribute out of a desire to help) and “I felt obligated to do so” (0 = did not contribute out of obligation, 1 = did contribute out of obligation). “Desire to help” represented a positive interpretation of the stressor and “I felt obligated to do so” represented a negative interpretation of the stressor. All additional response options were excluded due to a low number of participants selecting the remaining options.

X: Family Conflict

The dependent variable, family conflict, was measured using the binary survey question “Has there been any conflict or friction in your family related to student loans?” Answers were coded as 0 representing no and 1 representing yes. In a follow-up question for those who answered “Yes,” participants were also asked to “Please briefly explain the nature of conflict or friction in your family related to student loans.” While this open-ended follow-up question was not incorporated into the primary quantitative analysis, it was used to preliminarily investigate general themes and explanations for the experiences of spousal and parent–child conflict related to student loans. Qualitative findings from this open-ended question will be discussed following quantitative analysis.

Sample

Inclusion criteria for the national survey required participants to be between ages 25–75 and currently contributing to student loan payments for their own or a family member’s undergraduate or graduate education. To be eligible for the study, the participants’ loans were required to be for a non-profit college or university located in the United States. Individuals with loans for for-profit institutions were excluded due to the disproportionately lower degree completion rates, higher loan amounts, and higher default rates compared with non-profit institutions (Deming et al., 2013; Steele & Baum, 2009). Additionally, those with loans for associate degrees rather than bachelor’s and graduate degrees were excluded to achieve consistent outcomes; typically, associate degrees correspond with less student loan debt and lower degree completion rates (Baum et al., 2011). Quotas were also used for income to ensure varied representation from higher income brackets was achieved, given that college graduates have historically demonstrated higher earnings (Emmons et al., 2019).

This paper draws on a subset of the national survey sample (n = 700) consisting of parents who were currently contributing to student loan payments for an adult child’s higher education, with only one parent sampled per family. The total sample consisted of slightly more women (58%) than men (42%). Sample characteristics for the total sample, mothers and fathers are reported in Table 1.

In the total sample, the mean age was 59 years old and the majority identified as White (84%). Most participants were married (79%) and had more than one child (85%). Total principal loan amounts varied, with an average of 0.2 on a scale of 0–1. In general, participants were above the national median income level of $61,937 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Average household income was 0.3 on a scale of 0–1, with a majority of the sample (60%) reporting an income of at least $100,000, and 12% reporting an income of $200,000 or more. The sample was moderately knowledgeable about the loans on average (0.4 on a scale of 0–1), and most (86%) said their contribution amount was clear from the beginning. Seventy-four percent of the sample initially decided to contribute to loan payments out of a “desire to help,” and 34% “felt obligated to do so.” Just under a quarter of the sample (24%) reported experiencing conflict or friction in their family related to the loans.

Notably, the samples for mothers and fathers differed from each other in several regards. Men were older and had higher incomes than women on average, and were more likely than women to be White, married, have higher prior loan literacy, and contribute to student loans out of obligation. Additionally, women in the sample were more likely than men to experience family conflict about the loans.

Data Analysis

IBM SPSS version 25 was used for the download, cleaning, and analysis of data. Because the dependent variable, family conflict, is dichotomous, binary logistic regressions were used for quantitative analysis. To test for moderation as described in hypothesis 1, an initial regression analysis was performed with the inclusion of two-way interaction terms for total principal loan amount and all variables included in components B and C of the ABC-X model. Then, to explore the interacting role of gender as described in hypothesis 2, a second regression analysis was performed with the inclusion of two-way interaction terms for gender and all variables included in components A, B and C of the ABC-X model. Finally, to ease interpretation of any main effects for variables in the ABC-X model (hypotheses 3 and 4), non-significant interaction terms were removed from both models, and a final model was constructed. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test revealed a X2 (8) of 13.87 and was not significant (p > 0.05), suggesting that the final model is a good fit for the data used.

In addition, preliminary qualitative analysis assessed the nature of conflict about student loans for mothers and fathers. Responses were coded by respondent gender, family member dyad involved in conflict (parent–child, spousal, both, or other), and by variable of the ABC-X model. General themes described do not intend to capture the full nature of conflict for all participants, but rather to provide preliminary insight into common themes of parent–child conflict and spousal conflict related to student loans. Themes were highlighted to both strengthen confidence in factors used in the regression analysis and to illustrate the ways in which family conflict and its predictors may manifest within families, as well as to identify important factors of conflict for future work.

Results

Regression Results

Regression results testing for the moderating effects of resources and interpretations of the stressor (hypothesis 1) are reported in Table 2, regression results testing for possible gender interactions (hypothesis 2) are reported in Table 3, and results for the final regression model incorporating the significant interaction term identified in the prior two models, and testing direct effects of resources and interpretations of the stressor on family conflict (hypotheses 3 and 4), are reported in Table 4.

A: The Stressor

Total principal loan amount was a significant predictor of conflict in the final regression model (B = 0.998, p < 0.01).

B: Family Supports and Resources

Income did not moderate the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict about the loans, and was not significantly associated with family conflict. Prior loan literacy did not moderate the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict about the loans, but was a significant predictor of family conflict about the loans such that higher prior loan literacy was associated with less family conflict about the loans (B = − 0.723, p < 0.05). Clarity did not moderate the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict about the loans, but was a significant predictor of family conflict. Participants who said their contribution to the loans was clear from the beginning reported significantly less family conflict than those who said it was not clear (B = − 1.444, p < 0.01).

C: Interpretations of the Stressor

Neither contribution reason moderated the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict about the loans; however, individuals who contributed out of obligation were significantly more likely to experience family conflict about the loans than those who did not contribute out of obligation (B = 0.574, p < 0.01). Additionally, the interaction between contributing out of a desire to help and gender was significant (B = 1.153, p < 0.05). Following up on this finding, chi-square tests revealed that fathers who contributed out of a desire to help (15.0%) were significantly less likely to report family conflict than fathers who did not contribute out of a desire to help (30.4%), X2 (1, N = 295) = 8.26, p < 0.01) but there was no significant difference for mothers.

Sociodemographic and Control Variables

Age, number of children, and marital status were not significantly associated with family conflict. Race was a significant predictor of family conflict, with White participants reporting significantly more family conflict than non-White participants (B = 0.967, p < 0.01).

Gender did not interact significantly with total principal loan amount, income, clarity, prior loan literacy, or contributing out of obligation. Although the conditional effect of gender on family conflict in the final regression model was not significant, chi-square tests following up on the significant interaction between gender and desire to help revealed that although gender does not predict family conflict among individuals who did not contribute out of a desire to help, mothers who did contribute out of a desire to help (26.7%) were significantly more likely than fathers who contributed out of a desire to help (15.0%) to report family conflict about the loans, X2 (1, N = 511) = 10.08, p < 0.01).

Qualitative Results—Nature of Conflict

Participants who reported experiencing family conflict about student loans were also asked to “Please briefly explain the nature of conflict or friction in your family related to student loans” in an open-answer format. In total, 54 male responses and 104 female responses to this question were collected. Forty-seven responses noted parent–child conflict, 30 noted spousal conflict, and three noted both spousal and parent–child conflict. The remaining 78 responses either did not explicitly state the family members involved, or cited conflict with a family member other than a spouse or child. The following results focus on general themes extracted from responses relating to parent–child conflict and spousal conflict. While the nature of both types of family conflict referred to factors in the ABC-X model of family stress, the specific resources and interpretations of the stressor differed between the two types of conflict. In alignment with hypotheses 3 and 4 of the current study, these results illustrate the ways in which various protective resources (or a lack thereof) and interpretations of the stressor may contribute to parents’ experiences of spousal and parent–child conflict about the loans.

Parent–Child Conflict

When mothers and fathers explained the nature of parent–child conflict related to the loans, they most often referred to component B of the ABC-X model: the family’s protective resources.

Financial Resources

The lack of financial resources was a major cause of parent–child conflict for parents. In some cases, parent–child conflict relating to a lack of resources stemmed from children's difficulty in the job market, with several parents citing a child’s inability to enter a satisfactory career as the nature of conflict. One father explained that “my kid graduated and hasn’t found a job.” According to one mother, “not having found a job in my daughter’s field after graduation and having to pay a huge loan off is frustrating to say the least.” Another woman stated that conflict stemmed from “pressure for my son to get a high paying job with his degree. Instead, he got a minimum wage job that did not even require a degree. I am angry and disappointed.”

Others explained more generally how their child struggled financially, unable to pay their expected share of the loans. One mother shared that “we have to repay because son can’t afford it,” while another stated that her “daughter is suppose help pay and instead has to support her three children.”

For some parents, conflict arose from an inability to stretch financial resources across multiple children. One father shared that he was “unable to give equal support to 2nd student,” while another explained how his “child that got student loan did not get job worthy of the investment and sibling was jealous he was not able to receive same level of parental support due to parents debt load.”

Loan Literacy and Clarity Resources

In addition to a lack of financial resources, several parents cited a lack of knowledge about the loans or understanding of the repayment plan from the time of accrual. One mother explained that her “children were aghast at how much they owed upon graduation. They did not grasp what they had taken for loans themselves. At first, they held my husband and I responsible and felt we should pay their portion, until we showed them the huge amount we owed in comparison.” Similarly, a father shared that his “daughter feels we were not honest with her about the debt in her name with us as co-signors.” In other cases, parents attributed the lack of understanding to institutions outside of the family. One shared that “children are as angry as I am about the misinformation I was given and the underhanded way the loans were handled,” while another mother explained that “we were misled at the college financial aid sessions.”

Spousal Conflict

When mothers and fathers described spousal conflict related to the loans, some responses gave insight into the family’s protective resources, while others noted component C of the ABC-X model: the family’s interpretation or definition of the stressor.

Perceptions of Loan Repayment

The most common nature of spousal conflict related to parents’ reasoning for repaying the loans, often taking the form of mothers’ and fathers’ differing perceptions of the student loans. Several mothers demonstrated a desire to financially help their children pay for school, while fathers did not perceive repayment the same way. One father explained that “I did not want to co-sign any student loans. I wanted my son to work this out on his own. My wife felt we owed it to him and had to…It has created extreme tension between my wife and I.” Several mothers cited a similar disagreement regarding perceptions of the loans—one stated that “my husband didn't want to take out loans for school, but I felt we should provide some help,” while another woman said “I want to pay for children’s education because my parents paid for mine. Husband does not agree.”

Clarity Resources

In several cases, parents referred to the absence of clear agreement or discussion about repayment responsibility specifically. Mothers described challenges such as “arguing with spouse about who should pay them,” and “spouse not in full agreement for paying the loans,” while one father explained that his “wife upset at monthly payments thinks we should have done it differently.” Conflict for some stemmed from the feeling of student loans unexpectedly falling into one parent’s lap, rather than being anticipated from the beginning. One woman explained that “My husband was not happy when we had to take over payments of my daughter’s student loan and it caused problems in our marriage.” Another mother shared that “My husband left me 2 months after I consolidated our students loans to save money. He stopped paying, now I am legally obligated.” This report of an ex-husband reneging on repayment responsibility was mirrored by other mothers as well, in some cases leading to strain in other domains of life as well. According to one mother, it “requires me to work more causing stress and my ex-husband refuses to help.”

Relationship Quality and Communication Resources

Several parents—most of whom were women—cited broader relationship problems such as those noted above in describing the nature of conflict about the loans. For some, the issues related to trust, while for others, a lack of communication was the root issue. One mother explained that an “untrustworthy husband makes life more difficult.” The theme of broader relationship issues was particularly pertinent among divorcees. One mother shared that “her father/ my ex is the one who researched and provided the info for the loan. We trusted him and he ended up creating a huge financial mess for my daughter.” Regarding a lack of communication, one father mentioned his “ex-wife that has alienated my children making any kind of reasonable financial discussion impossible.”

Discussion

This study aimed to discover the factors influencing mothers’ and fathers’ experiences with student loan repayment for children, particularly in relation to their experiences of parent–child conflict and spousal conflict related to the student loans. Family Stress Theory highlights that the experience of family crisis, in this case family conflict, is influenced not only by the primary stressor, but also by the presence of a family’s protective resources or supports, as well as their interpretation of the situation. In alignment with this theory, the current study uncovered critical resources for families experiencing student loan debt, and ways in which mothers and fathers interpret financial stress and conflict differently in the context of student loan accrual and repayment.

A: The Stressor

While all participants shared the same key stressor—loan repayment for a child’s education—the stressor’s magnitude did play a role in the experience of family conflict. This finding is not surprising, as higher debt amounts tend to be associated with greater impacts to borrowers (Bozick & Estacion, 2014; Schwartz & Finnie, 2002).

B: Family Supports and Resources

In contrast to prior literature suggesting than higher earnings may buffer negative impacts of debt (Schwartz & Finnie, 2002; Tay et al. 2017), income was not a significant predictor of family conflict for the current sample, nor did it moderate the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict about the loans. This may be explained by the disproportionately high income levels of participants in the current study.

Prior student loan literacy arose as an important factor in parents’ experiences of family conflict such that those with higher levels of knowledge about the loans prior to accrual experienced less family conflict than those with lower levels of knowledge. Additionally, clarity about loan contributions from the beginning was associated with less family conflict, suggesting that in addition to baseline understanding of loan mechanisms, knowledge of one’s specific repayment plan is critical. Importantly, prior loan literacy and clarity about the loans had a direct effect on the experience of family conflict about the loans and did not moderate the effect of total principal loan amount, suggesting that having a robust understanding of student loans may be beneficial regardless of the quantity of loans being borrowed. These findings are consistent with Allgood and Walstad’s (2011) work, which revealed that in the context of credit card management, perceived financial knowledge—rather than actual financial knowledge—may more accurately predict financial outcomes.

Open-answer responses regarding parent–child conflict were consistent with this finding as well, as several mothers and fathers described a lack of clear information about the loans prior to their accrual. For these parents, parent–child conflict could be directly attributed to the lack of accurate or substantial information about the loan mechanisms or repayment prior to their accrual.

C: Interpretations of the Stressor

The current study suggests that mothers and fathers may differ not only in their reasons for contributing to loans, but also in the degree to which contribution reason prevents family conflict about the loans. Gender moderated the effect of contributing out of a desire to help; fathers who contributed out of a desire to help were significantly less likely to report family conflict than fathers who did not contribute out of a desire to help, but such a difference did not exist for mothers. Further, contributing to the loans out of obligation was significantly associated with greater family conflict, regardless of parent gender. These findings are consistent with prior Family Stress Theory literature, suggesting that negative perceptions of the stressor—in this case viewing loan contributions as an obligation rather than something desirable to do—may increase the likelihood of family crisis (Rosino, 2016). It should also be noted that—as was the case with family supports and resources—interpretations of the stressor did not moderate the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict, suggesting that viewing the student loans positively or negatively, regardless of the true quantity of the loans, may directly relate to parents’ experiences of family conflict about the loans.

Similar findings arose among open-answer responses as well, particularly in relation to spousal conflict. Several parents referenced the idea of being forced or obligated to contribute to repayment when they did not want to. A further layer of complexity that arose in these cases was inconsistency within couples regarding a desire to help. Sometimes, spousal conflict arose when the mother felt a desire to help, but the father did not. While this is the first study to investigate gender differences in family conflict related to student loans, these findings are consistent with prior literature suggesting that men and women tend to perceive and experience financial issues differently (Atwood, 2012; Zagorsky, 2003).

Further, themes that arose in open-ended responses about the nature of conflict suggest that mothers’ and fathers’ interpretations of student loan contributions may differ as well. This was particularly true for spousal conflict, where women often viewed the loans as a vehicle to assist their children, while men viewed them as something to be avoided. This finding aligns with descriptive statistics for the sample, in which fathers were significantly more likely than mothers to contribute to loans because they felt obligated to do so. While minimal literature has explored gender differences in reasons for contributing to children’s education costs, one explanation may be that in the context of large expenses, women tend to be more altruistic than men (Andreoni & Vesterlund, 2001), and due to social norms related to caring for family, mothers may more often expect to assist children with education costs (Goldscheider et al. 2001; Lye, 1996).

Demographic and Control Variables

Race was a significant predictor of family conflict, such that White respondents reported significantly more family conflict than non-White respondents. This finding should be interpreted with caution, given the lack of racial minority representation in the current sample. Despite prior research demonstrating that African Americans tend to have higher student debt burdens and lower financial resources, (Houle, 2014; Jackson & Reynolds, 2013) other work suggest that cultural differences may exist regarding expectations and goals of paying for children’s education—with racial minority groups placing a greater importance on saving for children’s education (Ouyang, 2019; Steelman & Powell, 1993).

Although marital status was not a significant predictor of family conflict in the regression model, qualitative analysis suggests that strength of the relationship may be an important factor, particularly for mothers, to explore for future research on spousal financial conflict. In alignment with prior literature identifying positive family relationships as a protective factor (Hill, 1958; Rosino, 2016), mothers in the sample who did experience spousal conflict mentioned relationship issues or divorce as a contributing factor. In several cases, divorce precipitated fathers reneging on repayment responsibility, causing increased financial or emotional strain for mothers. Several studies have supported this notion that parents—particularly fathers—tend to financially contribute less following divorce (Teachman, 1991; White, 1992). Further, past research suggests that divorce is associated with more severe financial impacts for women than men (Gadalla, 2008).

Number of children was not a significant predictor of family conflict related to the loans in the regression model. This contradicts prior literature that suggests that number of children may influence families’ experiences paying for children’s higher education (Grundy & Henretta, 2006; Sandefur, 2006). Despite this, a number of parents who experienced parent–child conflict did allude to the idea of thinned or unequal financial resources between their children in their open-ended responses, and in some cases, how this caused resentment from a child who received less support. While in some cases, it could be expected that more children would result in a thinning of financial resources and in turn, greater effects of loans on the family (Fingerman et al., 2015), the current study’s sample consisted of generally higher-income parents, which may have buffered this effect for families.

As discussed above in relation to interpretations of the stressor, gender significantly moderated the effect of contributing out of a desire to help in the regression model, a finding consistent with prior literature suggesting men and women perceived financial issues differently (Atwood, 2012; Zagorsky, 2003). Further, although gender did not predict family conflict among individuals who did not contribute out of a desire to help, mothers who did contribute out of a desire to help were significantly more likely than fathers who contributed out of a desire to help to report family conflict about the loans. This finding for parents who contributed out of a desire to help aligns with prior literature describing how women may experience greater financial stress and more difficulty with loan repayment than men (Dunn & Mirzaie’s, 2012; Schwartz & Finnie, 2002).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Given that this study utilizes primarily self-report measures, an inherent risk to the validity of responses may exist (Chan, 2009). Further, several survey questions required participants to answer questions regarding an earlier time in their lives. The items for prior student loan literacy, for example, asks participants to remember their knowledge about the loans in the past. For some participants, this could have required thinking back several years in the past. Given that memory fades with time, these measures may result in less accurate responses for some respondents. Further, people tend to recall memories from the past in a more positive light than they may have occurred, a phenomenon called positivity bias (Skowronski, 2011); consequently, it is possible that a larger portion of the sample did, in fact, experience family conflict earlier in the loan accrual or repayment process.

In addition, the binary measure of family conflict used for regression analysis captured the experience of family conflict generally, and thus parent–child conflict and spousal conflict could not be distinguished. A more nuanced measure asking parents if they had experienced conflict with a child, or with a spouse, about the loans would be necessary to achieve this.

Findings from this study cannot be generalized due to the lack of a nationally representative sample in several ways. Although intentionally focused to develop a picture of this specific, previously unstudied subset of individuals contributing to student loan payments, a wider and more diverse national sample would be necessary to achieve generalizability.

Implications for Future Research

Findings from the current study suggest the need for future research in related areas. While the importance of early financial training will be critical for parents accruing and repaying student loans for children, a review of these programs will be equally important to assess their effectiveness, as well as to determine which modules and topics specifically provide the best outcomes. Additionally, while this study highlights the commonality of conflict related to loans among parents and families, more research is needed to deconstruct the experiences of parent–child conflict and spousal conflict specifically, and to explore the content and themes of these unique types of conflict, as well as the areas of comfort and discomfort in related discussions. Future studies should test for the role of marital relationship quality, and should investigate further how married and divorced couples navigate these issues differently. In exploring these additional variables, utilization of path analysis would also be beneficial to further explore potential interactions and relationships among components of the model. Further, future work should consider inclusion of additional demographic information on the child loans are for, such as child age and gender. The inclusion of child gender would allow for a more nuanced exploration of gender differences, particularly related to how the loan repayment experience may vary for different parent–child dyads. Finally, considering the current study’s lack of a representative sample, it would be critical to explore how experiences of conflict vary across racial groups, as well as broader income and asset levels.

Implications for Practice

The significance of loan knowledge prior to accrual and clarity about the loans suggests the need for earlier financial education about student loans. Equipping people of all ages with the knowledge and tools to understand the mechanisms of funding a higher education may help mitigate the negative effects of debt later on, such as harmful conflict within families. Both prospective students as well as parents should fully understand the options that they have for paying for their own or their child’s education. While resources and priorities may be unique to each family, it is crucial that full understanding and clarity is achieved well before making any decisions about funding a higher education in any case.

Findings from this study suggest that there is a strong need for financial education and support in order to help mothers and fathers fully understand their options prior to taking out loans for children. The gender differences revealed by this study also reinforce the importance of making these tools available to and geared towards women, who have historically possessed lower levels of financial knowledge and have been shown to suffer greater psychological effects from the loans (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2008). Particularly for divorced mothers who may be experiencing greater financial strain and shifting financial responsibilities, financial education and support is paramount. It is critical that mothers and fathers receive financial training both prior to and throughout the loan repayment process to ensure they are well-equipped to plan for and manage higher education costs. Ensuring equal access to these resources across genders will be critical to mitigating historically prevalent inequities in outcomes.

This study also highlights the importance of family-centered support when deciding how to finance an education. The primary finding of this study regarded the occurrence of conflict within families, thus it is clear that not only the individual repaying loans experiences its effects, but the entire family. Further, gender differences in contribution reasons as well as parents’ disclosures about the nature of parent–child and spousal conflict suggest that while some themes are consistent for parents contributing to loans in general, mothers and fathers may not see eye to eye with their spouses. In turn, financial professionals or other institutions providing information and support for student loan borrowers should include family members in the discussion to promote improved knowledge and clarity from the start.

Conclusion

Results from this study forge new insights about mothers’ and fathers’ experiences repaying loans for children’s higher education. Though the sentiment of financial strain and family conflict were expressed by many participants, parents’ individual experiences with loan accrual and repayment are nuanced, differing across domains such as gender, reason for initially contributing, and knowledge and clarity about the mechanisms of and plans for loan repayment. Notably, findings from the current study suggest that rather than moderating the relationship between total principal loan amount and family conflict about the loans as the ABC-X model might suggest, families’ protective resources and interpretations of the stressor may be directly associated with the experience of family conflict—highlighting their importance regardless of the quantity of student loans one might have. As college costs continue to rise nationally, families will likely continue to grapple with the challenges and tensions associated with funding a child’s higher education. Insights from this study provide actionable implications for financial professionals and highlight the need for future research in this area, to ultimately improve outcomes for the multitude of parents repaying student loans for children.

References

Allgood, S., & Walstad, W. (2011). The effects of perceived and actual financial knowledge on credit card behavior. Networks Financial Institute Working Paper. http://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1896365

Almeida, D. M., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Everyday stressors and gender differences in daily distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 670. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.670

Almeida, D., Wethington, E., & Chandler, A. (1999). Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent-child dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/353882

Anderson, D. M., Conzelmann, J. G., & Lacy, T. A. (2018). The state of financial knowledge in college: New evidence from a national survey. Rand Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/WR1256

Andreoni, J., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355301556419

Asebedo, S. D., & Wilmarth, M. J. (2017). Does how we feel about financial strain matter for mental health? Journal of Financial Therapy. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1130

Atwood, J. D. (2012). Couples and money: The last taboo. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 40(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2011.600674

Barber, J. G., & Delfabbro, P. (2000). Predictors of adolescent adjustment: Parent-peer relationships and parent-child conflict. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17(4), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007546023135

Baum, S., Little, K., & Payea, K. (2011). Trends in community college education: Enrollment, prices, student aid, and debt levels. Trends in higher education series. https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-community-colleges-research-brief.pdf

Bozick, R., & Estacion, A. (2014). Do student loans delay marriage? Debt repayment and family formation in young adulthood. Demographic Research, 30, 1865–1891. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.69

Britt, S. L., Huston, S., & Durband, D. B. (2010). The determinants of money arguments between spouses. Journal of Financial Therapy, 1(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.4148/jft.v1i1.253

Britt, S. L., Mendiola, M. R., Schink, G. H., Tibbetts, R. H., & Jones, S. H. (2016). Financial stress, coping strategy, and academic achievement of college students. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 27(2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.27.2.172

U.S. Census Bureau (2019, October 29). U.S. median household income up in 2018 from 2017. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/09/us-median-household-income-up-in-2018-from-2017.html

Cha, K., Weagley, R. O., & Reynolds, L. (2005). Parental borrowing for dependent children’s higher education. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 26(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-005-5900-y

Chan, D. (2009). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences. (pp. 309–336). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Chen, H., & Volpe, R. P. (2002). Gender differences in personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review, 11(3), 289–307

Clarke, E. J., Preston, M., Raksin, J., & Bengtson, V. L. (1999). Types of conflicts and tensions between older parents and adult children. The Gerontologist, 39(3), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.3.261

Danes, S. M., & Haberman, H. (2007). Teen financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior: A gendered view. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 18(2). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2228406

Danziger, S., & Ratner, D. (2010). Labor market outcomes and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0041

De Clercq, B., & Venter, J. M. P. (2009). Factors influencing a prospective chartered accountant’s level of financial literacy: an exploratory study. Meditari: Research Journal of the School of Accounting Sciences, 17(2), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/10222529200900011

Deming, D., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. (2013). For-profit colleges. The Future of Children, 23(1), 137–163. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2013.0005

Dew, J. (2011). The association between consumer debt and the likelihood of divorce. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9274-z

Dew, J. P., & Stewart, R. (2012). A financial issue, a relationship issue, or both? Examining the predictors of marital financial conflict. Journal of Financial Therapy, 3(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/jft.v3i1.1605

Driva, A., Lührmann, M., & Winter, J. (2016). Gender differences and stereotypes in financial literacy: Off to an early start. Economics Letters, 146, 143–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.07.029

Dunn, L. F., & Mirzaie, I. A. (2012). Determinants of consumer debt stress: Differences by debt type and gender. Columbus: Ohio State University. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2331477

Emmons, W. R., Kent, A. H., & Ricketts, L. (2019). Is college still worth it? The new calculus of falling returns. The New Calculus of Falling Returns. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.101.297-329

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. (2019). Quarterly report on household debt and credit, February 2019. New York, NY: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/hhdc_2019q4.pdf

Fingerman, K. L., Kim, K., Davis, E. M., Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., Birditt, K. S., & Zarit, S. H. (2015). “I’ll give you the world”: Socioeconomic differences in parental support of adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(4), 844–865. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12204

Fonseca, R., Mullen, K. J., Zamarro, G., & Zissimopoulos, J. (2012). What explains the gender gap in financial literacy? The role of household decision making. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 46(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2011.01221.x

Gadalla, T. M. (2008). Impact of marital dissolution on men’s and women’s incomes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 50(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502550802365714

Gerrans, P., Speelman, C., & Campitelli, G. (2014). The relationship between personal financial wellness and financial wellbeing: A structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9358-z

Gicheva, D., & Thompson, J. (2015). The effects of student loans on long-term household financial stability. Student Loans and the Dynamics of Debt. https://doi.org/10.17848/9780880994873.ch9

Goff, B. S. N., & Smith, D. B. (2005). Systemic traumatic stress: The couple adaptation to traumatic stress model. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01552.x

Goldscheider, F. K., Thornton, A., & Yang, L. S. (2001). Helping out the kids: Expectations about parental support in young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(3), 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00727.x

Goldsmith, R. E., & Goldsmith, E. B. (2006). The effects of investment education on gender differences in financial knowledge. Journal of Personal Finance, 5(2), 55–69

Grable, J. E., Britt, S., & Cantrell, J. (2007). An exploratory study of the role financial satisfaction has on the thought of subsequent divorce. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 36(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X07309284

Grundy, E., & Henretta, J. C. (2006). Between elderly parents and adult children: A new look at the intergenerational care provided by the ‘sandwich generation.’ Ageing & Society, 26(5), 707–722. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X06004934

Gudmunson, C. G., Beutler, I. F., Israelsen, C. L., McCoy, J. K., & Hill, E. J. (2007). Linking financial strain to marital instability: Examining the roles of emotional distress and marital interaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(3), 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-007-9074-7

Hill, E. J., Allsop, D. B., LeBaron, A. B., & Bean, R. A. (2017). How do money, sex, and stress influence marital instability? Journal of Financial Therapy, 8(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1135

Hill, R. (1958). 1. Generic Features of Families under Stress. Social casework, 39(2–3), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389458039002-318

Houle, J. (2014). Disparities in debt: Parents’ socioeconomic resources and young adult student loan debt. Sociology of Education, 87(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040713512213

Jackson, B. A., & Reynolds, J. R. (2013). The price of opportunity: Race, student loan debt, and college achievement. Sociological Inquiry, 83(3), 335–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12012

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: How do women fare? American Economic Review, 98(2), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1094097

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial literacy around the world: An overview. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series (w17107). https://doi.org/10.3386/w17107

Lye, D. N. (1996). Adult child–parent relationships. Annual review of sociology, 22(1), 79–102. http://www.jstor.com/stable/2083425

MacDonald, M., & Koh, S. (2003). Consistent motives for inter-family transfers: Simple altruism. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 24, 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022435104422

Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008

Miller, J.B. (2019) Exploring the interaction of student loan debt and longevity planning within the context of the family (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA

Newland, R. P., Crnic, K. A., Cox, M. J., & Mills-Koonce, W. R. (2013). The family model stress and maternal psychological symptoms: Mediated pathways from economic hardship to parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031112

Ouyang, C., Hanna, S. D., & Kim, K. T. (2019). Are Asian households in the US more likely than other households to help children with college costs? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(3), 540–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09614-6

Papp, L. M., Cummings, E. M., & Goeke-Morey, M. C. (2009). For richer, for poorer: Money as a topic of marital conflict in the home. Family Relations, 58(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00537.x

Price, T. Rowe. (2015). 7th Annual parents, kids & money survey. http://www.multivu.com/players/English/7455231-t-rowe-price-financial-education/links/7455231-Please-Release-Parents-Kids-Money-Survey-PKM-Report-2015-FINAL.pdf

Rosino, M. (2016). ABC-X model of family stress and coping. Encyclopedia of Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119085621.wbefs313

Sandefur, G. D., Meier, A. M., & Campbell, M. E. (2006). Family resources, social capital, and college attendance. Social Science Research, 35(2), 525–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.11.003

Schwartz, S., & Finnie, R. (2002). Student loans in Canada: An analysis of borrowing and repayment. Economics of Education Review, 21(5), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00041-3

Skowronski, J. J. (2011). The positivity bias and the fading affect bias in autobiographical memory: A self-motives perspective. In M. D. Alicke & C. Sedikides (Eds.), Handbook of self-enhancement and self-protection (p. 211–231). The Guilford Press.

Steele, P., & Baum, S. (2009). How much are college students borrowing. https://www.cgsnet.org/ckfinder/userfiles/files/policy-brief-how-much-students-borrowing.pdf

Steelman, L. C., & Powell, B. (1991). Sponsoring the next generation: Parental willingness to pay for higher education. American journal of Sociology, 96(6), 1505–1529. http://www.jstor.com/stable/2781909

Steelman, L. C., & Powell, B. (1993). Doing the right thing: Race and parental locus of responsibility for funding college. Sociology of Education. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112754

Steen, A., & MacKenzie, D. (2013). Financial stress, financial literacy, counselling and the risk of homelessness. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 7(3), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v7i3.3

Taft, M. K., Hosein, Z. Z., Mehrizi, S. M. T., & Roshan, A. (2013). The relation between financial literacy, financial wellbeing and financial concerns. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(11), 63. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n11p63

Tay, L., Batz, C., Parrigon, S., & Kuykendall, L. (2017). Debt and subjective well-being: The other side of the income-happiness coin. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(3), 903–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9758-5

Teachman, J. D. (1991). Contributions to children by divorced fathers. Social Problems, 38(3), 358–371. http://www.jstor.org/stable/800604

Thorne, D. (2010). Extreme financial strain: Emergent chores, gender inequality and emotional distress. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9189-0

Walsemann, K. M., & Ailshire, J. A. (2016). Student debt spans generations: Characteristics of parents who borrow to pay for their children’s college education. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(6), 1084–1089. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw150

Wang, M., Supiano, B., & Fuller, A. (2012). The parent loan trap. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-parent-loan-trap/

White, L. (1992). The effect of parental divorce and remarriage on parental support for adult children. Journal of Family Issues, 13(2), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251392013002007

Yoder, K. A., & Hoyt, D. R. (2005). Family economic pressure and adolescent suicidal ideation: Application of the family stress model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.251

Zagorsky, J. L. (2003). Husbands’ and wives’ view of the family finances. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 32(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(03)00012-X

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge TIAA for contributing to this research.

Funding

This study was funded by TIAA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects, Protocol 674923) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is one of several papers published together in Journal of Family and Economic Issues on the “Special Issue on Couples, Families, and Finances”.

Appendix

Appendix

.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balmuth, A., Miller, J., Brady, S. et al. Mothers, Fathers, and Student Loans: Contributing Factors of Familial Conflict Among Parents Repaying Student Loan Debt for Children. J Fam Econ Iss 42, 335–350 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09761-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09761-9