Abstract

This paper examines definiteness marking in American Norwegian (AmNo), a heritage variety of Norwegian spoken in the US. The description adds another language to the much-studied variation within Scandinavian nominal phrases. It builds on established syntactic analysis of Scandinavian and investigates aspects that are (un)like Norwegian spoken in the homeland. A central finding is that the core syntax of Norwegian noun phrases is retained in AmNo, while the morphophonological spell-out is sometimes different. Indefinite determiners, for example, are obligatory in AmNo, but some speakers produce them with non-homeland-like gender agreement. One systematic change is observed: double definiteness has been partially lost. The typical AmNo modified definite phrase lacks the prenominal determiner that is obligatory for varieties in Norway. I argue that this is a syntactic change which allows the realization of D to be optional. This is a pattern not found in the other Scandinavian languages. At the same time, this innovative structure in AmNo is not like English, the dominant language of the AmNo speakers. This demonstrates heritage language change that is distinct from both the homeland language and the dominant language.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Scandinavian languages are closely related, but nevertheless vary in their nominal syntax. For instance, the way definiteness is marked, and in particular the presence or absence of so-called ‘double definiteness’, is subject to variation and has been described extensively (Taraldsen 1990; Delsing 1993; Santelmann 1993; Kester 1993, 1996; Vangsnes 1999; Julien 2002, 2005; Anderssen 2006, 2012; among others). These descriptions and syntactic analyses are based on the standard Scandinavian languages as well as their dialects.

In this paper, the picture of variation within Scandinavian is expanded by including heritage languages, in particular American heritage Norwegian (AmNo). As the result of migration in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, especially to North America, the Scandinavian languages are also spoken outside of their homelands (see Johannessen and Salmons 2015 for an overview). Following Rothman (2009), these languages are heritage languages because they were acquired at home, in a naturalistic environment, by children who also acquired the language of the national society.

Many studies on the language of bilingual heritage speakers find differences between the heritage language and the homeland variety, as well as variation among heritage speakers (see Montrul 2016; Polinsky 2018; Montrul and Polinsky 2021 for overviews). At the same time, heritage speakers have coherent and full-fledged grammars (Polinsky 2018, 350), and their language is better described in terms of innovation than in terms of loss or incompleteness (Yager et al. 2015).

The goal of the present paper is to examine the syntax of nominal phrases in AmNo, and to compare this with baseline Norwegian and the other Scandinavian varieties (see Sect. 3.4 for a discussion of the baseline). All speakers of AmNo are bilingual in Norwegian and English, with English being the language they use most on a daily basis. Therefore, the nominal phrases are also compared to English to explore whether changes in AmNo converge toward the contacting language.

A central finding of this study is that definiteness marking in AmNo is identical to the baseline to a very high degree. Despite its specific sociolinguistic situation, where bilingual speakers received limited and heterogeneous Norwegian input, there are only few differences with the baseline. Notably, differences are found in phrases that require double definiteness. While there is co-occurrence of a determiner and suffixed article in the baseline (1a), AmNo modified definite phrases typically only contain the suffix (1b).Footnote 1 In this respect, AmNo diverges from Norwegian as well as the other Scandinavian varieties, while it is not like English either. This innovation thus forms a unique pattern within the Scandinavian languages. In addition, the innovation shows that language change in heritage languages is not necessarily caused by transfer from the dominant language.

(1) | a. | den | hvit-e | hest-en |

DEF.SG | white-DEF | horse-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the white horse’ (baseline double definiteness) | ||||

b. | hvit-e | hest-en | ||

white-DEF | horse-DEF.M.SG | |||

‘the white horse’ (American Norwegian) | ||||

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the syntax of nominal phrases in the homeland Scandinavian varieties, building on the analysis by Julien (2005). Section 3 provides a background on heritage language syntax and introduces American Norwegian as well as the empirical foundation of the paper. In Sect. 4, the similarities between AmNo and baseline Norwegian are discussed, followed by a discussion of aspects where AmNo differs from baseline Scandinavian in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, the role of English is discussed. Section 7 concludes.

2 Scandinavian nominal syntax

The basic facts of the homeland Scandinavian nominal phrases are as follows. Indefinite phrases with a singular count noun contain a prenominal indefinite determiner.Footnote 2 This is illustrated for Norwegian in (2); the same pattern is found in the other Scandinavian varieties, except Icelandic, which does not have indefinite determiners. The indefinite determiner is used in the same way in indefinite phrases modified by an adjective (cf. (2a) with (2b)).

(2) | a. | et | hus | Norwegian | |

INDF.N.SG | house | ||||

‘a house’ | |||||

b. | et | stor-t | hus | ||

INDF.N.SG | large-N | house | |||

‘a large house’ | |||||

Definite phrases contain a definite article that is a suffix on the noun, as in the Norwegian example in (3). All Scandinavian languages use this definite suffix, except the Western Jutlandic dialects of Danish, which use a definite determiner instead (Julien 2005, 65–66).

(3) | hus-et | Norwegian |

house-DEF.N.SG | ||

‘the house’ | ||

Much more variation is found in definite phrases modified by an adjective or a numeral. In Norwegian, Swedish, and Faroese, the suffixed article co-occurs with a prenominal determiner in modified phrases (4a). This is known as double or compositional definiteness. Icelandic and the Northern Swedish dialects do not use the prenominal determiner (4b, c), while Danish modified definite phrases contain the prenominal determiner but not the suffixed article (4d).

(4) | a. | det | ny-e | hus-et | Norwegian |

DEF.N.SG | new-DEF | house-DEF.N.SG | |||

‘the new house’ | |||||

b. | nýja | hús-ið | Icelandic (Julien 2002, 264) | ||

new | house-DEF.N.SG | ||||

‘the new house’ | |||||

c. | ny-hus-et | Northern Swedish (Julien 2002, 264) | |||

new-house-DEF.N.SG | |||||

‘the new house’ | |||||

d. | det | nye | hus | Danish (Julien 2002, 264) | |

DEF.N.SG | new | house | |||

‘the new house’ | |||||

This variation in definiteness marking between the different varieties has received much attention in the field of Scandinavian syntax (see references in Sect. 1). In the languages with double definiteness, the prenominal determiner and the suffix co-occur and appear on different sides of the adjective. Therefore, Taraldsen (1990) argues for two projections above the noun, such that the determiner and suffix each have their own position in the syntactic structure. Since Taraldsen (1990), it is quite common in Scandinavian syntax to assume two determiner-like projections: a ‘low’ projection below the adjective, associated with the suffixed article, and a ‘high’ projection above the adjective, associated with the prenominal determiner.Footnote 3 While some studies analyze the determiner as an expletive element (e.g., Delsing 1993; Kester 1993), it has later been argued that both elements contribute to the definite semantics of the phrase (Julien 2002, 2005; Anderssen 2006, 2012). I adopt the latter analysis.

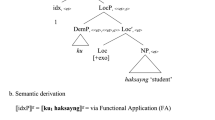

Adopting a generative, non-lexicalist approach to syntax (see also Sect. 3.1), I draw on Julien’s (2002, 2005) analysis of Scandinavian nominal phrases, provided in (5). From right to left, we find the following projections on top of NP: NumP, where features for number (singular or plural) are merged; ArtP, where the definite suffixed article is generated;Footnote 4αP which hosts adjectives (AP) in its specifier;Footnote 5 CardP which hosts numerals and other weak quantifiers in its specifier; and DP where the prenominal determiner is located. Julien (2002, 2005) assumes two positions on top of DP: one for demonstratives and one for strong quantifiers. These do not play a role in the analysis presented here and are therefore not included in (5).

(5) | Syntactic structure of the Scandinavian nominal structure |

[DP [CardP [αP [AP] [ArtP [NumP [NP [N]]]]]]] |

The projections CardP and αP are assumed to be merged only when they contain lexical material, while the other projections are merged in all referential nominal phrases. D is merged with unvalued features for gender, number, and definiteness (and case in the relevant varieties); these features are valued through agreement with a lower element.

A crucial assumption for Julien (2002, 2005) is that the DP-layer must be overtly realized or “identified” in referential phrases. In indefinite phrases, this identification happens by the insertion of the indefinite determiner in D, which likely originates as a weak quantifier in Card (Julien 2002, 273). In simple definite phrases that have no adjectival modification (and hence no αP or CardP), DP is identified through movement of ArtP (i.e., the noun with the suffixed article) to Spec-DP, illustrated in (6) with a Norwegian example.

(6) | Unmodified definite phrase in Norwegian |

[DP [ArtP [Art hus-et] [NumP [Num |

In modified phrases, however, this movement is blocked by the presence of αP (or CardP). The different Scandinavian languages have different strategies to identify D in these phrases. In the languages with double definiteness, D is identified by insertion of the prenominal determiner in D. This determiner expresses definiteness and phi-features through agreement with lower heads, enabling the phrase to be referential (Julien 2002, 278; 2005, 29–30). An example of the structure of double definiteness in Norwegian is given in (7). Swedish and Faroese modified definite phrases have the same syntax.

(7) | Modified definite phrase with double definiteness (Norwegian) |

[DP [D det] [αP [AP nye] [ArtP [Art hus-et] [NumP [Num |

Icelandic and the Northern Swedish dialects do not have double definiteness (see (4b, c)). Inspired by Vangsnes (1999), Julien (2002, 2005) analyses modified definite phrases in these languages as a case of αP-movement to Spec-DP. In other words, the whole αP—which contains both the adjective (in AP) and the definite noun (in ArtP)—moves to Spec-DP, as in (8). Since Spec-DP contains overt phonological material, D does not need to be lexicalized by a determiner. In Icelandic, the movement of αP occurs across CardP. However, Northern Swedish inserts a demonstrative in D when cardinal numbers are present (see Julien 2002, 283–291; 2005, 54–64 for details).

(8) | Modified definite phrase with sps upαsps downP-movement (Icelandic) |

[DP [αP [AP nýja] [ArtP [Art hus-ið] [NumP [Num |

Finally, Danish does not have double definiteness either; only the prenominal determiner is present in modified definite phrases (see (4d)). According to Julien (2002, 291; 2005, 65–67), the suffixed article and prenominal determiner are both realizations of D in Danish. As a result, they cannot co-occur. That is, unlike the other Scandinavian varieties, the Danish suffixed article is not hosted in Art, but in D. In simple phrases, ArtP moves to D and D is spelled out as the suffixed article; see (9a). In modified phrases, however, this movement is blocked, and D is realized as the prenominal determiner, illustrated in (9b).

(9) | a. | Simple definite phrase (Danish) |

[DP [D hus-et] [ArtP [Art | ||

b. | Modified definite phrase with single definiteness (Danish) | |

[DP [D det] [αP [AP nye] [ArtP [Art hus] [NumP [Num |

For reasons of space, the discussion above of nominal phrases in the different Scandinavian varieties is brief. I refer to Julien (2002, 2005) and references therein for more details. In this paper, I investigate the nominal syntax of American Norwegian, with a focus on its definiteness marking. Although AmNo is identical to the baseline in many ways, it is also unique among the Scandinavian varieties in some respects. Before turning to AmNo, however, I briefly discuss the syntax of nominal phrases in English, the dominant language of the AmNo heritage speakers.

Although a full analysis of the English nominal phrase lies beyond the scope of this paper, two important differences with Scandinavian should be kept in mind. First, English does not have grammatical gender and no gender features are present in the syntax or the agreement relations. Second, English does not have double definiteness but only prenominal (in)definite determiners. There is thus no need to postulate a low definiteness-projection, and I therefore assume that English lacks ArtP. Rather, the definiteness features are merged in D. The structure of English that is assumed here is given in (10) (see also Riksem 2018, 61 for a similar analysis).

(10) | Syntactic structure of the English nominal structure |

[DP [CardP [αP [AP] [NumP [NP [N]]]]]] |

In general, the English nominal phrase appears to be less complex than the Scandinavian ones. English noun phrases contain fewer features (no gender) and have fewer functional projections related to definiteness marking (no ArtP). However, as I discuss in Sect. 6, the AmNo nominal phrase is different from the English structure in (10), even in respects where it is unlike the other Scandinavian varieties.

3 Heritage language syntax and American Norwegian

3.1 Heritage language syntax

American Norwegian is a heritage language: it is a minority language acquired in a naturalistic context (i.e., as input to young children) by people who also speak—and are often dominant in—the societal language (cf. Rothman 2009, 156). Before AmNo and its speakers are introduced in the next section, some background on heritage language (HL) syntax is discussed here.

As argued by, among others, Lohndal et al. (2019) and Benmamoun (2021), data from heritage languages provide important insights for formal linguistics and syntactic theory. Heritage speakers acquire their language despite constrained input and pressure from the societal language. Investigating their syntax sheds light on which aspects of grammar can be acquired under these conditions (and are perhaps universal, cf. Benmamoun 2021) and which aspects require more extensive input or are vulnerable to change. In addition, systematic differences between heritage speakers and monolingual homeland speakers have been well documented (see the overviews in Montrul (2016); Polinsky (2018); Montrul and Polinsky (2021)). Therefore, heritage languages provide excellent opportunities to study linguistic variation, and this paper contributes to that line of work.

I assume that the syntax of heritage speakers follows the same principles and constraints as the syntax of monolingual speakers (Lohndal 2021, 644). Specifically, I adopt an exoskeletal (non-lexical) approach to syntax (Borer 2005a, b; Lohndal 2014), compatible with Julien’s (2002, 2005) analysis presented in Sect. 2. In this architecture, syntactic structures are independent from their morphological exponents, and morphological processes apply after syntactic structures have been generated. As pointed out by Benmamoun (2021), Lohndal (2021), and Putnam et al. (2021), data from heritage languages support this approach to syntax, since syntax has been found to be resilient to restructuring in heritage languages while morphology tends to be more vulnerable.

It is important to distinguish between core syntax and the morphophonological realization of syntactic structures. Core syntax includes syntactic features as well as the syntactic operations Merge, Move, and Agree (cf. Benmamoun 2021; Lohndal 2021);Footnote 6 it could be seen as the “machinery” that generates structures. After being generated in syntax, these structures are mapped onto morphophonological forms that realize (or spell out) the structure. I assume that this mapping is not part of core syntax, but rather a process following syntax. In other words, I maintain a distinction between the generation of structure (core syntax) and how those structures are realized (morphophonological realization). Benmamoun (2021) presents several examples where the difference between heritage speakers and monolingual speakers lies not in core syntax, but rather in the morphological realization, supporting the idea that these two elements are to be distinguished.

The mapping between syntactic structure and morphophonological form is often considered processing or performance related (Benmamoun 2021, 394; Lohndal 2021, 647; Putnam and Sánchez 2013). In this way, issues with morphophonological realization in heritage languages tend to be less systematic, and lead to inter- and intra-speaker variation. This contrasts with changes in core syntax, which are systematic and not related to performance issues (see Lohndal and Westergaard 2016; Kinn 2020, 19–21, Perez-Cortes et al. 2019, and Putnam and Sánchez 2013 for similar ideas).Footnote 7

For the present study, I did not measure processing or production difficulty systematically.Footnote 8 However, speech rate has been measured for some AmNo speakers, and it has been shown that speakers with a lower speech rate are more likely to omit the definite suffix (Van Baal 2019; see also Sect. 4.2 below). I use two main criteria to distinguish between changes in core syntax and issues of morphophonological spell-out. The first is systematicity: if something is subject to a high rate of inter- and intra-speaker variation, it is more likely related to spell-out of certain structures than to the syntax of these structures. Second, we will see that certain patterns generally occur in longer, more complex nominal phrases. This is likely also a factor in performance, and I therefore do not view these as the result of a change in the underlying grammar.

3.2 American Norwegian and its speakers

American Norwegian (AmNo) is a heritage language spoken in North America by descendants of Norwegian immigrants who arrived in the midwestern states of the US and in Canada during a period of large-scale migration between 1850 and the 1920s. In this period, around 850,000 Norwegians moved to North America, which gave Norway the second highest emigration rate in Europe at the time (Haugen 1953, 29). Although this migration came to an end a century ago, there are still some bilingual American-Norwegian speakers in areas where the migrants settled.

AmNo has a long history, and also a long research history. Historical data from the 1940s (Haugen 1953) have recently been digitized and made available online, which allows for studies of historical AmNo (see, e.g., Kinn and Larsson 2022). Here, I focus on AmNo as it is spoken today. All current speakers are descendants of Norwegians who immigrated to the United States prior to 1920. They are of advanced age and third- to fifth-generation immigrants, which is typical for the moribund Germanic heritage languages in the US (cf. Putnam et al. 2018).

These speakers grew up speaking Norwegian at home, and they typically acquired English when they started school, although some already received English input at home (especially when they had older siblings, Larsson and Johannessen 2015, 158). They grew up during a time where the Norwegian-American communities were undergoing a language shift and English was used more and more in the communities, including the local churches (see Haugen 1953; Natvig 2022). Most of the present-day speakers do not read Norwegian; they have received schooling in English only. This contrasts with previous generations, who often received some schooling in Norwegian churches and Sunday schools and read Norwegian-American newspapers. Today’s AmNo speakers typically only understand the dialects they have been exposed to during their childhood, which are mainly (but not exclusively) Eastern Norwegian valley dialects (Johannessen and Salmons 2012, 142). At present, all speakers are dominant in English and no longer use Norwegian for daily communication. Whether they have people around them to speak Norwegian with, and how frequently they speak Norwegian at present, is subject to considerable individual variation.

3.3 Empirical foundation

Much research on present-day AmNo is based on investigations of the Corpus of American Nordic Speech (CANS) (Johannessen 2015). In addition, some studies include elicited production data (e.g., Rødvand 2017; Lykke 2018; van Baal 2018). The analysis of definiteness marking presented here is based on the speech elicited for my dissertation (van Baal 2020). I used two elicited production tasks to elicit nominal phrases from 20 AmNo speakers. These tasks are briefly described below (see van Baal 2020, 71–84 for details).

In the translation task, a story was read sentence-by-sentence to the participants. The sentences were read aloud in English and the participants replied by giving a Norwegian translation of that sentence. The story consisted of 71 sentences in total and it contained 62 nominal phrases that were analyzed for this study. Four types of nominal phrases were elicited: simple (i.e., unmodified) indefinite phrases (n = 10), simple definite phrases (n = 35), modified indefinite phrases (n = 5), and modified definite phrases (n = 12).

The picture-aided elicitation task was based on the one developed by Rodina and Westergaard (2015a). Participants were presented pictures on a computer screen and asked to tell what they saw; this elicits indefinite phrases. Then, one picture would disappear, and participants would use a definite phrase to tell which item disappeared. Again, the task elicited simple indefinite phrases (n = 32), simple definite phrases (n = 32), modified indefinite phrases (n = 64), and modified definite phrases (n = 32). Both tasks elicited nouns in singular and plural form, and nouns from all three genders (m, f, n). All elicited production data was transcribed and analyzed manually.

In total, 20 speakers of AmNo participated in the picture-aided elicitation task, and 19 of them also participated in the translation task. The present analysis of definiteness marking in AmNo nominal phrases is based on the elicited speech data from these 20 speakers. All of them are elderly and third or fourth generation heritage speakers of Norwegian. The speakers come from three different states, North-Dakota, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, all of which are located in the American Upper Midwest.

3.4 Establishing a point of comparison

In this study, AmNo is compared to Norwegian spoken in Norway, the other Scandinavian languages, and English. It has often been argued that homeland speakers should not be the baseline in heritage language studies, and that the baseline should instead consist of the language that was the input to the heritage speakers (e.g., Benmamoun et al. 2013; Pascual y Cabo and Rothman 2012; Polinsky 2018, 11–16). For AmNo, a baseline is difficult to establish. Because of the long migration history, the present-day speakers are several generations away from the homeland,Footnote 9 and there are not always data or studies on previous generations of AmNo speakers. Most studies on AmNo therefore take spoken homeland Norwegian as a point of comparison. They expand this baseline by including the dialects from the Norwegian immigrants and, if available, data from older AmNo speakers. This approach to the baseline is for example adopted in Johannessen and Larsson (2015) and van Baal (2020). I adopt the same strategy here.

For definiteness marking, differences between standard Norwegian and the baseline dialects are related to the morphophonological shape of definiteness morphemes, rather than to their presence or absence. In other words, the facts about the indefinite article, definite suffix, and double definiteness in Norwegian presented in Sect. 2 also apply to the baseline dialects. With respect to double definiteness (the aspect where, as we will see below, present-day AmNo is different from homeland Norwegian), previous generations of heritage speakers behaved the same as homeland speakers (Van Baal 2022). It is therefore fair to assume that double definiteness was part of the input, and hence of the baseline.

In the next two sections, the data from AmNo will be compared to the baseline. It is important to stress that this comparison is made on purely descriptive grounds, and not in a deficit-oriented way (see Lohndal 2021, 647). In the same way that the Scandinavian languages differ from each other (see Sect. 2) without one language being a “wrong” version of the others, AmNo is described here as a viable variety of Scandinavian, with the goal of adding yet another variety to the picture of Scandinavian definiteness marking. Similarities between AmNo and baseline Norwegian are presented next in Sect. 4, followed by a discussion of differences between AmNo and the baseline in Sect. 5.

4 Similarities between AmNo and the baseline

This section discusses the similarities between AmNo and the baseline, which was established in the previous section. Utterances that are in some respect unlike the baseline might at first attract much attention from both researchers and naïve monolingual speakers alike. However, the similarities between monolingual and heritage varieties are equally important from a theoretical point of view, as they can shed light on the elements that can be acquired under the reduced (and different) input that most heritage speakers receive, as well as demonstrate which elements tend to be unaffected by the lack of use across the speakers’ lives (see also Sect. 3.1 and Benmamoun 2021). For example, it has previously been found that the word order in main clauses is rather stable in AmNo, while the word order in subordinate clauses is more frequently non-baseline-like (Larsson and Johannessen 2015). Even the infrequent and pragmatically marked pronominal demonstrative is used in AmNo in a stable manner (Kinn and Larsson 2022).

In the present study on nominal phrases in AmNo, the first important observation is that indefinite and definite morphemes are used in a way that suggests they have the same semantics as in baseline Norwegian. Although we will see some examples of the omission of definiteness morphemes below, it is important to note that the morphemes are not used in a pragmatically strange context. In other words, the speakers do not use indefinite determiners in definite phrases or vice versa. They do not combine indefinite and definite determiners either. Secondly, it can be observed that the phrase-internal word order in AmNo is the same as in baseline Norwegian. Some examples to illustrate this are given in (11).Footnote 10

(11) | a. | to | svart-e | hest-er | |

two | black-PL | horse-PL | |||

‘two black horses’ (sunburg_MN_11gk) | |||||

b. | noen | blå | blom-er | ||

some | blue | flower-PL | |||

‘some blue flowers’ (sunburg_MN_06gm) | |||||

c. | de | tre | rød-e | bøk-ene | |

DEF.PL | three | red-DEF | book-DEF.PL | ||

‘the three red books’ (iola_WI_05gm) | |||||

In the examples above, cardinal numbers and other weak quantifiers (e.g., noen ‘some’ in (11b)) appear before adjectives, which in turn precede the nouns. In the definite phrase in (11c), the determiner appears on the left edge of the phrase. This is the exact same word order in as in homeland Norwegian, viz. determiner – cardinal – adjective – noun (also the word order in English). The data do not contain any examples of post-nominal adjectives or numerals, nor an adjective-numeral order. Furthermore, demonstratives are only found before the noun (and adjective if present). No post-nominal determiners or demonstratives have been observed in AmNo, and these word orders are also absent from CANS.Footnote 11 In other words, AmNo does not diverge from the baseline when it comes to phrase internal word order.

In the remainder of this section, I present cases where definiteness marking in AmNo is identical to the baseline. Indefinite phrases are discussed first (Sect. 4.1), followed by unmodified definite phrases with singular nouns (Sect. 4.2).

4.1 Indefinite phrases

Indefinite singular DPs with count nouns are obligatorily preceded by an indefinite determiner in all Scandinavian languages except for Icelandic (see Sect. 2 above).Footnote 12 AmNo is the same in this respect and uses indefinite determiners in indefinite singular phrases, as in the examples in (12)–(13). Like in the other Scandinavian varieties, both unmodified and modified indefinite phrases in AmNo contain the indefinite determiner; cf. (12) with (13).

(12) | a. | en | konvolutt | |

INDF.M.SG | envelope | |||

‘an envelope’ (fargo_ND_01gm) | ||||

b. | et | glass | ||

INDF.N.SG | glass | |||

‘a glass’ (westby_WI_01gm) | ||||

(13) | a. | en | hvit | hest |

INDF.M.SG | white | horse | ||

‘a white horse’ (coon_valley_WI_10gm) | ||||

b. | ei | lita | jente | |

INDF.F.SG | little.F | girl | ||

‘a little girl’ (coon_valley_WI_06gm) | ||||

The indefinite determiner is analyzed as the realization of D in indefinite singular phrases (see Sect. 2). In AmNo, the indefinite determiner takes the same position; i.e., it occurs in D as in the other Scandinavian varieties. Among all singular indefinite phrases elicited for this study, 69.38% contain the indefinite determiner. This may seem rather low for a language with obligatory determiners. However, the rate is very high in the translation task (96.67%), where context in the form of a sentence is present, while it is lower in the picture-aided elicitation task (67.47%), where nouns were often named in isolation. In the picture-aided elicitation task, the vast majority of the phrases without an indefinite determiner were not part of a sentence (80.6%). This suggests that AmNo speakers’ use of the indefinite determiner (partially) depends on the presence of the sentence around it. It is possible that there is no full DP-projection present when nouns are only named in isolation. When the indefinite determiner is omitted from a sentence, there are often pauses or hesitations while the speaker is searching for the word. Issues with lexical retrieval may be another reason for the occasional omission of the indefinite determiner. Putting these cases aside, the indefinite determiner is used in a stable and baseline-like manner in AmNo.

Elements in D inflect for definiteness, number, and gender and the indefinite determiner agrees with the features present on the noun (Julien 2005, 12). In (12)–(13), we see examples of indefinite determiners in all three genders. Masculine, feminine, and neuter determiners are found across the population of AmNo speakers, and all speakers in Rødvand (2017, 83) showed at least traces of a three-gender system. However, it is well-documented that individual AmNo speakers produce indefinite determiners that do not agree with the gender of the noun (Johannessen and Larsson 2015; Lohndal and Westergaard 2016; Rødvand 2017). Typically, the masculine gender is overused on nouns that are feminine or neuter, as in the phrases in (14).Footnote 13

(14) | a. | en | hus |

INDF.M.SG | house(N) | ||

‘a house’ (fargo_ND_01gm, baseline: et hus) | |||

b. | en | hand | |

INDF.M.SG | hand(F) | ||

‘a hand’ (sunburg_MN_18gk, baseline: ei hand) | |||

These examples illustrate some of the observed non-baseline-like inflection of indefinite determiners. Of the indefinite determiners in unmodified phrases, 81.35% are inflected in a baseline-like manner (individual scores: between 42.86% and 100%). In phrases modified by an adjective, 66.77% of the indefinite determiners are inflected similarly to baseline Norwegian (individual scores: 29.41–95.56%). Although the gender inflection of indefinite determiners is somewhat unstable in AmNo, there are no speakers with a completely restructured gender system.

In my analysis, phrases such as those in (14) are not the result of syntactic differences between AmNo and homeland Norwegian. Both varieties place an indefinite determiner in D in singular indefinite phases, and in both varieties, there is syntactic agreement between the noun and D. Instead, the difference lies in the morphophonological spell-out of the feature bundles in D, leading to the production of non-baseline-like forms of indefinite determiners. Given the lack of systematicity in these phrases, this should be seen as a performance issue. The fact that non-baseline-like indefinite determiners are more frequently observed in complex nominal phrases than in simplex ones (also observed by Johannessen and Larsson 2015) furthermore indicates that performance factors are at play, rather than there being a change in core syntax.

The description above focuses on singular indefinite phrases. Plural indefinite phrases differ from singular ones, in that they do not obligatorily combine with a determiner. Plural indefinite phrases have an empty D, although they may combine with the indefinite plural determiner noen ‘some’ (Julien 2005, 20). Plural number is expressed in these phrases with a plural suffix, but some nouns (mainly neuter ones) occur in their bare form in the indefinite plural.

American Norwegian plural indefinite phrases do not differ from baseline ones. They are inflected for number, as in (15a–b), or occur in their bare form as in (15c) in the same way as in baseline Norwegian. In addition, the data contain examples with the indefinite plural determiner, as in (11b) above.

(15) | a. | to | høne-r |

two | chicken-PL | ||

‘two chickens’ (sunburg_MN_07gm) | |||

b. | stor-e | hend-er | |

large-PL | hand.PL-PL | ||

‘large hands’ (iola_MN_05gm) | |||

c. | to | bord | |

two | table(N) | ||

‘two tables’ (ulen_MN_01gm) | |||

In the data in the present study, plural indefinite phrases in AmNo behave exactly like those in the baseline, and there is no evidence that they would have different syntactic structures. This means they have an empty D (unless the determiner noen ‘some’ is present) and a plural suffix as the realization of the Num-head with a plural feature.

4.2 Unmodified, definite singular phrases

As noted in Sect. 2, the Scandinavian languages use definite suffixes in unmodified definite phrases. This definite suffix is generally retained in AmNo. However, the data show a difference between singular phrases and plural phrases: while definite singular phrases behave very much like the baseline, definite plural phrases are often different. The latter are therefore discussed in Sect. 5.1, and this section discusses singular definite phrases which are unmodified by adjectives or numerals.

The definite suffix is used in a stable way in AmNo, occurring with a high degree of consistency on nouns that are definite: 90.9% of the unmodified singular definite phrases have the definite suffixed article. The suffix is only occasionally left out, and omission is only observed in a small subgroup of the speakers. Some examples of the baseline-like definite singular suffix are given in (16).

(16) | a. | fisk-en |

fish-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the fish’ (sunburg_MN_12gk) | ||

b. | hånd-a | |

hand-DEF.F.SG | ||

‘the hand’ (westby_WI_01gm) | ||

c. | kjøkken-et | |

kitchen-DEF.N.SG | ||

‘the kitchen’ (fargo_ND_09gm) |

The definite suffix is productive in AmNo. Speakers use it in contexts where it is obligatory, and only in these contexts. The definite singular article is not used in indefinite contexts or combined with indefinite determiners. Another sign of its productivity is that the definite suffix is used on nouns that are originally English. This is illustrated in (17) for one speaker, but this is a pattern found for all of them. For more on Norwegian-English language mixing, see Grimstad et al. (2014), Grimstad et al. (2018), Riksem (2017), and Riksem et al. (2019), who analyze the patterns in an exoskeletal framework consistent with the approach I use here (see Sect. 3.1).

(17) | a. | farm-en |

farm(ENG)-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the farm’ (sunburg_MN_15gm) | ||

b. | road-en | |

road(ENG)-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the road’ (sunburg_MN_15gm) |

The facts that the suffix is used consistently, that it is restricted to definite phrases, and that it occurs on English borrowings indicate that the suffix is added productively in definite contexts, rather than that the noun and suffix form an unanalyzed ‘chunk’ in the speakers’ grammar. Lohndal and Westergaard (2016, 11) suggest that chunking may explain the relatively stable use of gender marking on the definite suffix. However, if the noun and suffix would form a chunk, it could be expected that the chunk would occur in non-definite contexts; this does not happen. Instead, it seems clear that the suffix is a realization of Art in AmNo, as in the baseline (see Sect. 2). The definite suffix is used consistently even though English, the dominant language of the speakers, does not have definite suffixes. The role of English on AmNo is discussed in Sect. 6 in more detail.

As with indefinite determiners, the presence of the definite article is baseline-like, while the form of the suffix is sometimes divergent. The morphophonological form of the suffix is occasionally unlike baseline Norwegian, as in (18) below, but this happens much less frequently than with indefinite determiners (Johannessen and Larsson 2015; Lohndal and Westergaard 2016). In my data, 95.52% of the definite suffixes in unmodified phrases have a baseline-like form (in accordance with the gender of the noun), whereas the rate is 81.35% for indefinite determiners (cf. Sect. 4.1 above). Again, I do not analyze this as a syntactic difference from the baseline, but rather as a difference in morphophonological realization of the feature bundles, caused by performance factors.

(18) | a. | flagg-en |

flag(N)-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the flag’ (westby_WI_06gm, baseline: flagg-et) | ||

b. | bok-en | |

book(F)-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the book’ (sunburg_MN_06gm, baseline: bok-a)Footnote 14 |

For both indefinite determiners (Sect. 4.1) and definite suffixed articles on singular nouns (Sect. 4.2), the data indicate that AmNo is identical to baseline Norwegian when it comes to the underlying syntax. However, in both cases, the morphemes are occasionally realized in a different morphophonological form. In other words, while the core syntax of AmNo is unchanged, the spell-out of feature bundles is vulnerable in some speakers.

5 Differences between AmNo and the other Scandinavian languages

The previous section discussed the syntactic similarities between American Norwegian and the baseline. In this section, I present three cases where AmNo is unlike baseline Norwegian, and in fact, unlike all the other homeland Scandinavian languages as well. First, Sect. 5.1 discusses the difficulty with definite plural suffixes and analyzes this as a difference in spell-out rather than in underlying syntax. In Sect. 5.2, modified definite phrases which require double definiteness are discussed. I argue that AmNo has a syntax unlike the other Scandinavian varieties, although it at first glance seems similar to Icelandic and Northern Swedish. Finally, Sect. 5.3 considers demonstrative phrases that are syntactically like the baseline but seem to have a pragmatically different use.

5.1 Definite plural phrases

In AmNo, the definite suffixed article occurs with singular nouns with high consistency (see Sect. 4.2). On plural nouns, on the other hand, the definite suffix is less stable. The elicited production data contain phrases that have the indefinite plural suffix while the phrase has a definite meaning. In total, 73% of the definite plural phrases occur with the definite plural suffix; the remainder contains an indefinite plural suffix (or no suffix at all). This is observed in both simple and modified phrases, but it is more frequent in the latter (76.9% of the simple phrases have the plural suffix, 67.1% of the modified phrases).

The phenomenon of indefinite plural marking in definite phrases is illustrated below for unmodified (19a–b) and modified (20a–b) phrases.Footnote 15 In these examples, (a) illustrates the (baseline-like) use of the indefinite plural suffix, and (b) the use of the same suffix in a definite phrase. Both examples come from the picture-aided elicitation task; the indefinite phrases were elicited as responses to the question “What do you see here?” and the definite phrases were responses to the question “What disappeared?” In other words, the semantic and pragmatic contexts for these phrases were clearly indefinite in (a) and definite in (b).

(19) | context: indefinite | context: definite | ||

a. | blom-er | b. | blom-er | |

flower-PL | flower-PL | |||

‘flowers’ | ‘the flowers’ (intended) | |||

(sunburg_MN_04gk) | ||||

(20) | context: indefinite | context: definite | ||||||

a. | to | hvit-e | høne-r | b. | to | brun-e | høne-r | |

two | white-PL | chicken-PL | two | brown-DEF | chicken-PL | |||

‘two white chickens’ | ‘the two brown chickens' (intended) | |||||||

(sunburg_MN_11gk) | ||||||||

These examples show cases where indefinite plural and definite plural suffixes are no longer distinguished from each other. A unified plural is used in indefinite as well as definite contexts. Unified plurals can be found in non-heritage Germanic languages, viz. in the languages around the North Sea (English, Dutch, West Frisian). Unlike in these languages, the unified plural is not used consistently in AmNo. It is important to note that the majority of the plural definite phrases in AmNo still contains the baseline-like definite suffix, as in (21).Footnote 16

(21) | a. | blom-ene | |

flower-DEF.PL | |||

‘the flowers’ (coon_valley_WI_06gm) | |||

b. | brun-e | høne-ne | |

brown-DEF | chicken-DEF.PL | ||

‘the brown chickens’ (sunburg_MN_09gm) | |||

There is considerable inter-speaker variation with respect to the use of the definite plural suffix. Two speakers use it consistently, others occasionally use the indefinite plural in definite contexts, and still others rarely use the definite plural. The percentage of definite plural phrases with a baseline-like definite plural suffix ranges from 100% to as low as 17.7% (the average across participants is 71.3%).

The AmNo unified plural suffix that is used regardless of the definiteness feature may be explained as change in the syntax or in morphophonological spell-out. First, it may be the case that the two functional projections for number (Num) and definiteness (Art) have merged into one single projection where the two features are bundled. For heritage Spanish in the US, Scontras et al. (2018) argue that the projections for number and gender (which are separated in monolingual Spanish) have merged to a single projection, leading to instability in the inflection as the two features are no longer recognized individually. Riksem (2017) proposes a merged functional projection for number, definiteness, and gender features in AmNo (and for homeland Norwegian as well, Riksem 2017, 95–96). However, while Scontras et al. (2018) is based on comprehension data, similar data are lacking for AmNo. In order to confirm a bundled feature representation, such comprehension data would be necessary.Footnote 17 Moreover, we have seen in Sect. 4 that the indefinite plural suffix (the spell-out of Num) and the singular definite suffix (the spell-out of Art) are both highly stable in AmNo. Given that AmNo and the baseline are similar in this respect, there is little independent evidence to assume different underlying structures.

An alternative is that the vulnerability of plural definite suffixes occurs at the level of spell out, when the syntactic structure is matched onto morphophonological forms. Inflectional plural morphology has been found to be vulnerable to change in several other heritage languages, including heritage Arabic (Albirini et al. 2011; Benmamoun et al. 2014) and heritage Hungarian (Bolonyai 2007). Håkansson (1995) finds an overuse of indefinite plurals in definite contexts in heritage Swedish, as in (22).Footnote 18

(22) | de | sydlig-a | städ-er | (heritage Swedish, Håkansson 1995, 170) | |

DEF.PL | southern-DEF | state-PL | |||

‘the southern states’ | |||||

baseline Swedish: de sydlige städ-er-na | |||||

The vulnerability of the definite plural suffix in AmNo seems to fit into this often-observed vulnerability of plural morphology. As noted above, the definite plural suffix is more vulnerable in modified (complex) than unmodified (simple) phrases. This suggests that performance factors play a role. The feature bundle [def, pl] is less stable in AmNo than the number and definiteness features in isolation.

The fact that the feature bundle [def, pl] is often realized (or spelled out) as only a plural feature can be captured in terms of an impoverishment rule. Impoverishment involves the “deletion of morphosyntactic features from morphemes in certain contexts” (Harley and Noyer 1999, 6; see also Bonet 1991). It is a process that applies after the syntactic structure is generated, and before it is spelled out. Potentially, an impoverishment rule is active in AmNo which deletes the definiteness feature from feature bundles that contain a plural feature.Footnote 19 In other words: after syntax has generated a structure containing this feature bundle, Impoverishment changes this feature bundle (to [pl] only), with the result that another morphophonological form (-erpl instead of -enedef.pl) is matched to it. This rule, however, is not applied consistently,Footnote 20 as there are no speakers in the data set of the present study who never use the definite plural suffix.

It is difficult (if not impossible) to determine on empirical grounds whether performance issues influence the spell out of the feature bundle, or whether there is an active Impoverishment rule. In either case, I analyze the use of indefinite plural suffixes in definite contexts as a difference in morphophonological realization compared to the baseline, and not as a change in syntax. The underlying syntax that creates the feature bundle [def, pl] is identical to that of baseline Norwegian and the other Scandinavian languages, with separate projections for number and definiteness (Num and Art, see Sect. 2). When these features need to be realized in isolation (as a plural indefinite or a definite singular suffix), the AmNo speakers behave consistently, as discussed in Sect. 4.

5.2 Modified definite phrases

Modified definite phrases are the place where most variation among the Scandinavian varieties is found (see Sect. 2). Norwegian is one of the languages with double (or compositional) definiteness, where a prenominal determiner co-occurs with the definite suffix when the phrase is modified by an adjective or numeral. Double definiteness is observed in AmNo as well, as in the examples in (23). In addition, cases of adjective incorporation are found, where the adjective is compounded to the definite noun and no definite determiner is present, as in (24). Adjective incorporation is common in some of the baseline dialects and should therefore also be considered baseline-like.

(23) | a. | den | hvit-e | hest-en |

DEF.SG | white-DEF | horse-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the white horse’ (sunburg_MN_09gm) | ||||

b. | den | blå-e | bok-a | |

DEF.SG | blue-DEF | book-DEF.F.SG | ||

‘the blue book’ (iola_WI_05gm) | ||||

c. | det | stor-e | skip-et | |

DEF.N.SG | large-DEF | ship-DEF.N.SG | ||

‘the large ship’ (sunburg_MN_12gk) | ||||

(24) | a. | rød-blomster-n |

red-flower-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the red flower’ (flom_MN_01gm) | ||

b. | brun-dør-a | |

brown-door-DEF.F.SG | ||

‘the brown door’ (westby_WI_06gm) | ||

c. | gul-hus-an | |

yellow-house-DEF.PL | ||

‘the yellow houses’ (coon_valley_WI_10gm) |

In addition to these baseline-like modified definite phrases, my data contain a large proportion of non-baseline-like phrases that lack double definiteness. In fact, only 25.92% of the modified definite phrases by the AmNo speakers are baseline-like (190 out of 722 phrases).Footnote 21 In both elicitation tasks, the speakers score significantly lower on modified definite phrases than on the other types of phrases.Footnote 22

Four types of non-baseline-like modified definite phrases can be observed in AmNo. Most often, the prenominal determiner is omitted, as in (25). Almost half of the elicited phrases lacked the prenominal determiner (n = 339, 46.25%) and all speakers use such phrases very frequently. In the semi-spontaneous interviews and conversations in CANS, a high proportion of the modified definite phrases occurs without the prenominal determiner (Anderssen et al. 2018).

(25) | a. | hvit-e | hest-en |

white-DEF | horse-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the white horse’ (sunburg_MN_07gm, baseline: den hvite hesten) | |||

b. | grønn-e | fugl-en | |

green-DEF | bird-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the green bird’ (westby_WI_11gm, baseline: den grønne fugl-en) | |||

Modified definite phrases without the suffixed article (n = 35, 4.77%) and phrases that lack both determiner and suffix (n = 123, 16.78%) are less frequent. The former type is illustrated in (26a), the latter in (26b).

(26) | a. | den | stor-e | jordbær |

DEF.SG | large-DEF | strawberry | ||

‘the large strawberry’ (sunburg_MN_11gk, baseline: den store jordbæra)Footnote 23 | ||||

b. | stor-e | skip | ||

large-DEF | ship | |||

‘the large ship’ (fargo_ND_09gm, baseline: det store skipet) | ||||

Both these types are often observed in plural phrases. Recall from Sect. 5.1 that the definite plural suffix is vulnerable for some speakers. This vulnerability was found in non-modified and modified phrases alike, and therefore does not reflect a specific issue with double definiteness. When only singular phrases are considered, suffix omission is found in 4.72% of the modified definite phrases, and bare phrases in 12.08% of them. This is much less frequent than determiner omission, for the group and for individual speakers as well. While all speakers frequently omit the determiner and produce phrases like (25), suffix omission or bare phrases are only produced by a subgroup of the speakers. These speakers typically produce only a few instances of phrases like (26).Footnote 24

The fourth type of non-baseline-like modified definite phrases contains a demonstrative rather than a prenominal determiner, but this is not very frequent (n = 46, 6.28%). It is discussed further in Sect. 5.3.

Compared to determiner omission, suffix omission in modified definite phrases is much less frequent and less systematic. In Sect. 4.2, it was discussed that the suffixed article was used in a very stable way in unmodified definite phrases. Its omission is somewhat more common in modified (i.e., longer and more complex) definite phrases, but it is still not frequent. In addition, suffix omission is found in speakers who are less fluent or proficient in AmNo, measured in terms of speech rate and vocabulary knowledge (Van Baal 2019). Together, this suggests that suffix omission is related to performance factors rather than the result of a change in underlying grammar.

Omission of the prenominal determiner in modified definite phrases, however, appears to be different. It is very frequent and consistent, both for the group and for individual speakers. All but two AmNo speakers have a higher rate of suffix inclusion than determiner inclusion in singular modified definite phrases, meaning that they (much) more frequently omit the determiner than the suffix.Footnote 25 Therefore, the typical modified definite phrase in AmNo lacks the prenominal determiner and only contains the suffixed article. This is then a systematic difference from baseline Norwegian, where double definiteness is obligatory.Footnote 26,Footnote 27

The AmNo modified definite phrases without the determiner are, at least superficially, similar to Icelandic and Northern Swedish, the Scandinavian languages that do not use prenominal determiners. Modified definite phrases in Icelandic and Northern Swedish have been analyzed as the result of movement of αP (which includes the adjective and the definite noun in Art) to Spec-CP (see Sect. 2). In Icelandic, αP moves across CardP, such that cardinal numbers appear at the end of the linear string. In Northern Swedish, a demonstrative is inserted in D when cardinal numbers are present (Julien 2002, 283–291; 2005, 54–64). In both languages, αP-movement is only possible when an overt noun is present. In cases of ellipsis, a demonstrative or determiner occurs obligatorily in D (ibid).

The restrictions on αP-movement in Icelandic and Northern Swedish make it possible to test whether this movement also takes place in AmNo. If AmNo exhibits αP-movement, the syntax of modified definite phrases without a determiner could be accounted for. The elicited production data for this study contain 77 phrases with a cardinal number and 15 phrases with ellipsis of the definite noun. In total, there are 92 contexts to test whether αP-movement can account for determiner-less modified definite phrases. If AmNo demonstrates αP-movement, we would expect this to be prohibited in phrases with cardinal numbers or ellipsis. In those phrases, we then expect the determiner to be present.

However, this is not the pattern found in the AmNo elicitation data. More than half of the phrases with a cardinal or ellipsis (n = 55, 59.78%) do not contain a determiner. Out of the phrases with a cardinal number, about two-thirds lack the determiner (53 out of 77 phrases, 68.83%), which is even more frequent than for phrases modified by an adjective. An example is given in (27a), and earlier in (20b).Footnote 28 For the cases with ellipsis, the determiner is frequently present, but not in all cases: 13.33% lack the determiner, as in (27b).

(27) | a. | to | brun-e | hund-ene |

two | brown-DEF | dog-DEF.PL | ||

‘the two brown dogs’ (westby_WI_06gm, baseline: de to brune hundene) | ||||

b. | hvit-e | |||

white-DEF | ||||

‘the white one’ (fargo_ND_09gm, baseline: den hvite) | ||||

The phrases in (27) would require a determiner-like element (or demonstrative) in Northern Swedish, and the same is true for (27b) in Icelandic. In other words, AmNo seems to behave differently regarding contexts where movement of αP to Spec-DP is impossible. While Icelandic and Northern Swedish lack a determiner only in phrases where αP can move, AmNo modified definite phrases lack determiners in all contexts. In the AmNo data, no restrictions or patterns can be distinguished, and the prenominal determiner is omitted frequently by all speakers. Therefore, it is unlikely that AmNo exhibits αP-to-Spec-DP movement.Footnote 29 A much more plausible analysis is that the definite determiner—i.e., the spell-out of D—is optional in AmNo, such that D can be empty in modified definite phrases. This then results in the typical AmNo modified definite phrase without a determiner, as in (28). For this phrase, I assume the syntactic structure in (29), where D can be spelled out as a determiner (den) or remain empty (Ø). The latter happens frequently in AmNo, leading to phrases like (28) and those in (25).

(28) | vesle | hand-a | |

small.DEF | hand-DEF.F.SG | ||

‘the small hand’ (ulen_MN_01gm) | |||

(29) | Modified definite phrase in American Norwegian |

[DP [D den / Ø] [αP [AP vesle] [ArtP [Art hand-a] [NumP [Num |

For phrases like (28), without a prenominal determiner, it may not be clear whether the D-layer is present at all. Potentially, AmNo could lack DP (a so-called NP-language), or modified definite phrases could be small nominals. Neither analysis for AmNo is compelling. Börjars et al. (2016) and Lander and Haegeman (2014) (among others) argue that the Scandinavian languages have developed from NP-languages to DP-languages. However, the characteristics of NP-languages do not match with the data from AmNo that we have seen in this paper. Determiners in AmNo are obligatory—not in modified definite phrases, but the indefinite determiner is obligatory (Sect. 4.1)—and take a fixed position in the phrase. Furthermore, determiners and determiner-like elements (such as demonstratives) are in complementary distribution, and AmNo has a stable phrase-internal word order. All this is at odds with the characteristics of NP-languages (Börjars et al. 2016),Footnote 30 and it is therefore clear that AmNo has a grammaticalized DP-layer.

Pereltsvaig (2006) discusses that even languages with a DP-layer can exhibit nominal phrases without this layer, so-called small nominals. She argues that small nominals are not referential and, as a result, cannot have specific reference (see Pereltsvaig 2006, 494–495 for the other characteristics). However, the modified definite phrases in the present study are all definite in meaning and are by definition specific. Their definiteness and specificity are expressed by the definite suffixed article which is, as we have seen, very stable in AmNo. The phrases are furthermore referential, referring either to the protagonists in the story of the translation task or to the pictures on the screen in the picture-aided elicitation task.

In other words, the modified definite phrases without a determiner do not conform to the characteristics of NP-languages or small nominals. Rather, they are exactly this: a phrase without an overt prenominal determiner. None of the syntactic analyses proposed for other (Scandinavian) languages is easily extended to AmNo, as clear counterevidence for all of them exist. AmNo is better understood as a language where D can be empty in modified definite phrases, as in (29), resulting in phrases like (25) and (28). This captures the fact that the prenominal determiner can be omitted in AmNo, even in contexts where it cannot in Icelandic and Northern Swedish, and at the same time acknowledges that D is present in these definite, referential phrases. Note that although D can be empty, it does not have to be—sometimes, double definiteness is still present in AmNo (see the examples in (23) at the start of this section). The overt realization of D is optional in AmNo.

Three of the speakers in the present study never use double definiteness in modified definite phrases. Two of them occasionally produce the determiner in a phrase without the suffix, and the third speaker never produces the determiner. This speaker may have lost the determiner completely, and D is therefore never realized in modified definite phrases. At the same time, the optionality of the determiner allows for inter- and intra-speaker variation. In this respect, it is not surprising that we observe variation with respect to how frequently the determiner is used by individual AmNo speakers.

The analysis presented here may seem at odds with the general observation that heritage speakers avoid null elements or empty heads, referred to as the “Silent Problem” (Laleko and Polinsky 2017). This conclusion is based on heritage language speakers’ disfavor of discourse-licensed silent elements (viz. anaphoric dependencies in topic marking and subject pro-drop). In these cases, both overt and silent heads occur in the baseline and discourse pragmatics determines which option to use. In my view, double definiteness is a different type of phenomenon, because there are no pragmatic conditions on omission of the determiner, and there are no different interpretations for phrases with or without the determiner. In addition, the determiner is not necessary for referent-tracking in the same way as pronouns and topic markers are. The avoidance of null-elements when these have a discourse function is clear in heritage speakers (Laleko and Polinsky 2017), but it seems to me that omission of other elements—like the determiner in modified definite phrases—is not automatically at odds with this. In addition, other phenomena have been documented where heritage languages show an increase in null elements (or traces) compared to the baseline: parasitic gaps in heritage German (Bousquette et al. 2016) and preposition stranding in heritage German (Bousquette 2018) and heritage Spanish (Pascual y Cabo and Gómez Soler 2015).

5.3 The ‘overuse’ of demonstratives

Although demonstrative phrases were not intentionally elicited, my data contain a certain number of them. As noted in the previous section, a few speakers used the demonstrative in the place of the prenominal determiner in modified definite phrases. Some examples are given in (30). Phrases like these, with an unexpected demonstrative, are not very frequent. They constitute 6.28% of the elicited modified definite phrases (n = 46). Ten speakers produce at least one demonstrative phrase, but only two of them frequently exchange the determiner for a demonstrative (≥ 10 phrases).

(30) | a. | denne | hvit-e | hest-en |

DEM.SG | white-DEF | horse-DEF.M.SG | ||

‘the/this white horse’ (fargo_ND_01gm) | ||||

b. | disse | gul-e | hus-a | |

DEM.PL | yellow-DEF | house-DEF.PL | ||

‘the/these yellow houses’ (sunburg_MN_15gm) | ||||

c. | denne | blå-e | bok-a | |

DEM.SG | blue-DEF | book-DEF.F.SG | ||

‘the/this blue book’ (ulen_MN_01gm) | ||||

All phrases in (30) are baseline-like in syntactic terms, as the demonstrative is combined with a noun that carries the definite suffixed article. The speakers may intend a demonstrative meaning or use the demonstrative anaphorically, to refer to a just-mentioned item.Footnote 31 Although anaphoric demonstratives are possible in the baseline, there is nothing in the translation task or picture-aided elicitation task that specifically calls for a demonstrative. These phrases are thus somewhat surprising on semantic-pragmatic grounds, and could be seen as overuse of demonstratives.Footnote 32 The demonstratives in (30) are therefore translated as ‘the/this’ to reflect the unclear semantics.

Baseline Norwegian has two sets of demonstratives: proximal (denne ‘this.sg’, dette ‘this.n.sg’, disse ‘this.pl’) and distal (den ‘that.sg’, det ‘that.n.sg’, de ‘that.pl’). The latter group is morphologically identical to prenominal determiners, but the two are distinguished based on prosody and stress (Faarlund et al. 1997, 327), and they are considered different lexemes (Anderssen 2006, 118). Since determiners and demonstratives are different lexical items, and because the few speakers who produce phrases like (30) also produce determiners, it is unlikely that there has been a change in AmNo grammar. It is more likely that these speakers, occasionally, overuse the demonstrative form in contexts where this is semantically or pragmatically not necessary.

Interestingly, the overuse of demonstratives has been observed in Argentine Danish as well, where some speakers produce demonstratives in phrases that would have the prenominal determiner in homeland speakers (Jan Heegård Petersen, p.c.). Possibly, a similar process is underway in the two languages, where some speakers use pragmatically unnecessary demonstratives. Unfortunately, pragmatics is a relatively under-researched topic for heritage languages (cf. Polinsky 2018, 291), and future research would be necessary for a description and analysis of the (over-) use of demonstratives.

6 The role of English

A recurrent topic in heritage language linguistics is whether heritage speakers are influenced by the majority language when they speak their heritage language. First, it is important to distinguish between direct transfer and contact-induced change. In contact varieties like AmNo, where all speakers are bilingual, there can be changes which are not the result of copying a certain structure or aspect from the dominant language. For example, Yager et al. (2015) find a case of differential object marking (DOM) in several varieties of heritage German. This pattern is not present in the baseline and does not come from the dominant language of these speakers either (Yager et al. 2015, 8). Instead, it is an example of contact-induced change.

In addition, some scholars make a distinction between transfer and other types of cross-linguistic effects, relating transfer to changes in the linguistic representations, and cross-linguistic effects to performance factors (e.g., Rothman et al. 2019, 23–26). Others use the terms interchangeably or do not make a distinction between different forms of cross-linguistic influence (CLI). Westergaard (2021), for example, argues that all forms of CLI are related to parsing and processing. The ways in which CLI potentially shapes heritage languages would deserve its own article. In this section, I only briefly touch upon the topic of whether AmNo is—in any respectFootnote 33—more similar to English than to the baseline. In other words, I discuss whether transfer from English can be observed in the potential places for it.

An important observation is that there are aspects where AmNo is identical to Norwegian, despite the fact that English is different. The gender agreement of the indefinite determiner is such a case: one could have imagined that gender in AmNo was lost under the influence from English, a language without grammatical gender. However, we saw in Sect. 4.1 that the majority of indefinite determiners inflects in a baseline-like way, and that no speakers have completely lost or restructured their gender system (Johannessen and Larsson 2015; Lohndal and Westergaard 2016; Rødvand 2017). There is thus no systematic influence from English on the inflection of indefinite determiners, although there are some cases of non-baseline-like forms. I argued that these occur at the level of spell out, where some speakers occasionally seem to fall back on the default and most frequent masculine gender.

A similar observation can be made about the definite suffixed article. This is a morpheme that does not exist in English, and it is the realization of a syntactic projection absent from English (see Sect. 2). Potentially, influence from English could have led to loss or vulnerability of the definite suffix in AmNo. In Sect. 4.2, we have seen that the contrary is the case: the use of the definite singular suffix in unmodified definite phrases is highly stable in AmNo. Occasionally, the definite suffix has a non-baseline-like form. However, it is hard to explain this by influence from English, as there are no definite suffixes in English at all. In these two cases—gender agreement and the definite suffix—there are no systematic differences between AmNo and the baseline, and English has not had an effect on the heritage language. In similar vein, Bousquette and Putnam (2020) and Nützel and Salmons (2011) find that complementizer agreement in American German is retained despite the absence of an analogous construction in English.

Now, we move to cases where AmNo is different from baseline Norwegian, to see if these can be explained by transfer from English. We saw in Sect. 5.1 that the definite plural suffix is often realized as the indefinite plural and that many speakers seem to use a unified plural suffix. This may be a case of influence from English, which has a unified plural suffix as well (-s on both indefinite and definite plural nouns). At the same time, it has to be noted that a unified plural also occurs in other Germanic (non-heritage) languages, so they do not need to be the result of contact with English. The unified plural may furthermore reflect a general tendency towards simplification found in many heritage languages, and more research on heritage languages in contact with other languages than English—a language with generally very little inflectional morphology—is necessary to tease the two options apart (cf. Scontras et al. 2015, 3, for a similar argument).

Finally, the instance where a systematic change between AmNo and the baseline is observed is in modified definite phrases. In AmNo, double definiteness is no longer obligatory in phrases modified by an adjective. However, the morpheme that is retained in AmNo is the suffixed article and not the prenominal determiner, while English only has the latter. In other words, the typical AmNo modified definite phrase is not like English and its difference from the baseline cannot be explained by direct transfer from English. Modified phrases with only the definite suffix are not present in either the baseline or English; they are an innovation that could be considered the result of contact-induced change.

Based on corpus data in CANS, Anderssen et al. (2018) also note that modified definite phrases in AmNo are typically different from English.Footnote 34 They also investigate possessive phrases. Norwegian exhibits both prenominal and postnominal possessives, while English only uses the former. Anderssen et al. (2018) find that the postnominal possessive—the one not found in English—is most frequent in AmNo. Many speakers use this more frequently than monolingual speakers, while only a small subset of the speakers produces many prenominal possessives. Interestingly, Anderssen et al. (2018) find a correlation between the type of possessive a speaker uses and their behavior in modified definite phrases. Speakers who frequently use postnominal possessives tend to leave out the prenominal determiner, while speakers who often use prenominal possessives are more likely to omit the definite suffix. There are only few speakers in this latter group, but these speakers typically use structures where Norwegian and English are similar (i.e., the prenominal possessive and prenominal determiner). Anderssen et al. (2018) argue that these speakers are influenced by transfer from English, and they furthermore suggest that these speakers are less proficient in Norwegian than the other speakers.

In summary, there is hardly any transfer from English in AmNo. First, there are phenomena that have not changed in AmNo despite its contact with English (gender agreement, the definite suffix). In addition, in the case that we do find change in AmNo (modified definite phrases without the determiner), this is a contact-induced change with an innovative pattern rather than transfer from English.

7 Concluding remarks

This paper describes definiteness marking in American Norwegian (AmNo), a heritage variety of Norwegian spoken in North America by descendants of Norwegian immigrants. The aim of the present study was to compare the nominal syntax of AmNo with baseline Norwegian, other Scandinavian varieties, and English, the dominant language of the speakers. In this description, a distinction is made between core syntax and the morphophonological spell-out of the syntactic structure. Based on elicited production data, similarities and differences between AmNo and the baseline were identified.

In most respects, the syntax of AmNo nominal phrases is identical to that of homeland Norwegian as described by Julien (2002, 2005). The same functional projections are found, including two distinct projections for the definite suffixed article and the prenominal determiner. In Sect. 4, indefinite phrases and definite singular unmodified phrases were described as identical to the baseline, apart from some surface variation in the morphophonological spell-out of the indefinite determiner and definite suffix. This leads to some non-baseline-like forms, but it does not represent a change in the underlying syntax. Rather, it is another example of how the morphophonological realization of syntax may be vulnerable, while the syntactic structure itself is stable in heritage languages, as observed in other heritage languages (cf. Benmamoun 2021; see Sect. 3.1 above).

Sect. 5 presented cases where AmNo is different from the baseline. The definite plural suffix is often realized through a unified plural suffix (Sect. 5.1), but no speaker seems to have restructured their system completely. I therefore propose that a change in the spell-out rules of the feature bundle [def.pl] may have occurred. Although this is a somewhat systematic change, it is related to morphophonological realization rather than to core syntax. Section 5.3 discusses how a few individuals use demonstratives rather than prenominal determiners. This may reflect a tendency in heritage speakers to be explicit, and relates to pragmatics-semantics, an area for which more research on AmNo is needed.

The only clear case of a change in AmNo compared to baseline Norwegian is double definiteness in modified definite phrases (Sect. 5.2). In AmNo, the prenominal determiner is typically omitted, while the suffixed article is present in a stable way. Because this is observed systematically across speakers and types of data, I argue that this represents a change in AmNo. Although the AmNo modified definite phrase is superficially similar to both Icelandic and Northern Swedish, I show that the underlying syntax is distinct. Rather than moving αP to Spec-DP, as in these varieties, AmNo speakers simply leave the D-projection unrealized.

It is not unsurprising that it is double definiteness that has changed in AmNo, while other types of definiteness marking have not. Double definiteness is an infrequent phenomenon (cf. Dahl 2015, 121; Anderssen et al. 2018), which is acquired late even by monolingual children (Anderssen 2006, 2012). It also poses challenges in bilingual acquisition (Anderssen and Bentzen 2013) and for second language learners of Norwegian (Nordanger 2017; see also Axelsson 1994 for L2 Swedish). As Kupisch and Polinsky (2022) point out, change can happen faster (“on fast forward”) in heritage languages compared to the homeland language, especially when pressure from the standardized written language is absent, as is the case for American Norwegian.

As heritage language speakers, AmNo speakers get less input and fewer opportunities to use their language than monolingually raised speakers in the homeland. Yet, despite these different circumstances and the speakers’ dominance in English, the syntax of AmNo nominal phrases is remarkably similar to that of homeland Norwegian. With respect to double definiteness, AmNo differs from homeland Norwegian as well as other Scandinavian varieties by omitting the prenominal determiner and not realizing D. It furthermore differs from previous generations AmNo speakers (Van Baal 2022). This difference shows a new pattern in the Scandinavian languages that is not attested in Julien (2005). At the same time, this pattern is not like English either. In this respect, the heritage language data show the creative aspect of language acquisition which leads to language change. Rather than a copy of the input or of the dominant language, the heritage language exhibits a new pattern.

Moreover, the data presented here show that innovative patterns can arise even in the final generation of speakers, in a heritage language in a moribund state. The emergence of innovations has been observed in other moribund heritage languages. Yager et al. (2015), for example, discuss the restructuring of case marking to DOM marking in different heritage varieties of German. This indicates that speakers of a moribund language do not have a reduced or decayed grammar; on the contrary, they have full-fledged grammars in which new patterns can emerge, just like they do in other, non-moribund languages (see also Bousquette & Putnam 2020).

The AmNo pattern in modified definite phrases is, as far as I am aware, unique for the Scandinavian languages. This case illustrates the benefit of including heritage languages into comparative and theoretical work. They enhance our understanding of possible variation in human language and the factors that influence it, precisely because heritage languages often differ from the homeland variety or baseline. Future work on definiteness marking in other Scandinavian heritage languages can complete the picture of the Scandinavian nominal phrase. It would be especially interesting to investigate whether American Swedish and Latin American Norwegian show the same loss of the prenominal determiner in modified definite phrases that we have seen in (North) American Norwegian.

Notes

Examples in (American) Norwegian are rendered in Bokmål, one of the written standards of Norwegian. The following abbreviations are used in the glosses: def=definite, dem=demonstrative, f=feminine, indf=indefinite, m=masculine, n=neuter, pl=plural, sg=singular.

The data for this paper only contain count nouns, and I will therefore not discuss mass nouns. Other exceptions where the indefinite determiner can be omitted are not discussed either.

See Börjars et al. (2016) for an alternative analysis that assumes only one functional projection (DP).

See Julien (2002, 267–268) for arguments that adjectives occur in the specifier of αP and not as heads in the syntactic structure.

Benmamoun (2021, 378) uses the terms External Merge and Internal Merge rather than Merge and Move.

When working with the AmNo speakers, one can observe that it is sometimes difficult for them to speak Norwegian, their heritage language. Illustrative are the number of pauses, and difficulties with lexical retrieval (‘looking for words’). That this is a performance issue is clear from the fact that it tends to improve after having spoken Norwegian for a while (i.e., they need to ‘warm up’, see also Polinsky 2018, 82).

All AmNo utterances are rendered in standard Bokmål Norwegian orthography. Each example is presented together with a code referring to the individual AmNo speaker who uttered the phrase. The code consists of the speaker’s hometown, a unique number, and a combination of letters indicating the speaker’s age and gender (u = speaker under fifty, g = speaker over fifty, m = male speaker, k = female speaker). The speaker cited in example (11a) is thus living in Sunburg, Minnesota, has the index number 11, and is a woman older than 50.