Abstract

Mothers of autistic children encounter numerous daily challenges that can affect their adaptation. While many studies have documented the impact on mothers of having an autistic child and factors contributing to their adaptation and their experiences of motherhood, few have examined how mothers of autistic children perceive their overall adaptation. We investigated with a qualitative design how mothers of autistic children perceive stressors, facilitators (resources, coping strategies, and contexts), and outcomes of adaptation in various life domains. Participants included 17 mothers of autistic children ranging from 2 to 8 years old. Mothers participated in a phone interview about their perception of their successes, challenges, and adaptation as mothers of their children. A thematic analysis was conducted on interview transcripts using inductive and deductive coding. A cross-case analysis was subsequently used to identify themes and subthemes. Results highlight the complexity of the maternal adaptation process in the context of autism, which starts before the child’s diagnosis. Stressors, facilitators, and outcomes were described as overlapping in the psychological, social, professional, marital, and parental life domains. The accumulation of stressors was identified as mothers of autistic children’s main source of stress and almost impossible to reduce. Participants explained having difficulties accessing effective facilitators. While outcomes of adaptation vary across mothers and life domains, indicators of distress were identified for all participants. Implications are discussed regarding how service providers and society could better support mothers of autistic children by considering their complex reality and by providing more resources and information.

Highlights

-

Mothers of young autistic children participated in semi-structured interviews about their adaptation process.

-

The adaptation process starts before the child’s diagnosis. Stressors, facilitators, and outcomes overlap between life domains.

-

The accumulation of stressors is identified as the main source of mothers’ stress and is almost impossible to reduce.

-

Outcomes of adaptation vary across mothers and life domains, yet all mothers mention at least one indicator of distress.

-

Service providers should focus on offering more resources to mothers to promote better access to effective facilitators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that is diagnosed in approximately 2% of children in Canada and the United States. Autistic children exhibit in early childhood deficits in the areas of communication and social interactions, as well as patterns of behaviors including rigidities, sensory peculiarities, stereotypical behaviors, and/or strong and sometimes unusual interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). These children include four times more boys than girls and display varied clinical profiles. Furthermore, the majority of autistic children have one or more co-occurring difficulties (e.g., attention deficit, anxiety, learning disabilities, epilepsy, etc.) (Maenner et al., 2021; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021).

Being the parent of a young child leads to several personal, professional, marital, and social changes that can be both challenging (Saxbe et al., 2018) and rewarding (Nelson et al., 2014; Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020), which might be especially true for mothers of autistic children. Indeed, mothers of autistic children often face changes in their perspective toward life, daily routines, career paths, and relationships with their spouse, family members, and friends (Corcoran et al., 2015; Dieleman et al., 2018; Ooi et al., 2016). On the one hand, mothers of autistic children can develop a new vision in life, experience self-growth, and empowerment, and become more in the moment (De Clercq et al., 2022; Dieleman et al., 2018) and appreciative of the little things (Corcoran et al., 2015; Ooi et al., 2016; Smith & Elder, 2010). On the other hand, they also often encounter additional challenges in exercising their parental role, in part due to their child’s characteristics. Indeed, they report having to fulfill not only the role of the mother, but also that of therapist (e.g., implementing therapeutic exercises and interventions at home) and advocate (e.g., educating others on autism, finding services, and pursuing a non-evident search for a diagnosis), which generates a colossal workload (des Rivières-Pigeon & Courcy, 2014; Safe et al., 2012). This workload is an integral part of basic parental responsibilities involving many cognitive (e.g., thinking about difficulties that could arise at the park or daycare and planning how to prevent them), domestic (e.g., cooking meals and cleaning), educational (e.g., teaching social and communicational skills), and care tasks (e.g., giving the bath, putting the child to bed and soothing the child), on a daily and continuous basis. Nevertheless, this workload is often complex and invisible to others (des Rivières-Pigeon & Courcy, 2017; Dieleman et al., 2018). Furthermore, mothers are particularly exposed to the challenges of parenthood and those associated with autism, since they assume a higher proportion of care for the child and domestic work than their spouse (Davy et al., 2022; McAuliffe et al., 2019). They also tend to live in a context of constant uncertainty as the development of young autistic children and their social integration are difficult to predict. In addition, parents of an autistic child describe experiencing a lot of isolation and stigma from members of the community who do not fully understand their reality (Dieleman et al., 2018; Nicholas et al., 2016; Woodgate et al., 2008). Mothers of autistic children therefore seem to face significant challenges adapting to their life context.

The Concept of Adaptation

The concept of adaptation refers to the idea that when faced with stressors, the individual tries to maintain a balance between the satisfaction of personal needs and taking into account the demands of the environment to which the individual must respond. The individual then sets up regulatory processes, such as the use of resources and coping strategies (Tarquinio & Spitz, 2012) that act as facilitators in “preserving, improving and adjusting” (Ordre des psychoéducateurs et psychoéducatrices du Québec, 2014, p. 12, as translated by Périard-Larivée, 2023) his/her level of functioning (outcomes). For example, when a woman becomes the mother of an autistic child, she is faced with the challenge of trying to balance her own needs, such as sleep and maintaining significant relationships, with several daily stressors, such as managing the child’s difficulties and complex needs, advocating for services and facing stigma. Facilitators, such as resources (e.g., social support and services) and coping strategies (e.g., “letting go” and reframing the vision of the situation), may then help the mother adjust to the situation (Corcoran et al., 2015; Dieleman et al., 2018). Several qualitative and quantitative studies have documented outcomes for mothers of autistic children that result from the process of adapting to the challenges they face. For instance, mothers of autistic children report higher levels of parental stress, psychological distress (Estes et al., 2013; Hayes & Watson, 2013; Miranda et al., 2019) and burnout than mothers in the general population (Kütük et al., 2021). According to a scoping review by Davy and her colleagues (2022), they also have lower participation in the labor market and take less part in leisure or social activities than mothers of neurotypical children, due to changes made to accommodate their parental responsibilities. They may also experience strain in their relationship with their spouse (Corcoran et al., 2015; Ooi et al., 2016). Thus, the adaptation process of mothers of autistic children spans several life domains, namely psychological (e.g., their psychological well-being), social (e.g., relationships with friends and extended family), professional (e.g., participation in the labor market and occupation), marital (e.g., spouses’ relationship) and parental (e.g., family life and parental role).

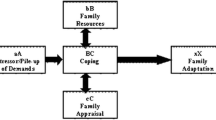

Furthermore, according to Dalle Mese and Tarquinio (2012), the concept of adaptation, which refers both to a state and a process, should be studied using a global and integrative approach rather than narrower concepts. Therefore, studies should look not only at stressors, coping strategies, resources, and outcomes of adaptation of mothers of autistic children, but also at how the combination of all these factors informs the maternal adaptation process. The most widely used model of parental adaptation in autism, which tends towards such a global approach, is the double ABCX Model of Family Stress and Adaptation (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983). This multivariate model suggest that families’ process of adaptation can be described by the interrelations of several factors that play a role in the short and long term : the initials stressors faced by the family (A), the additional demands that accumulate over time (aA), the family’s existing (B) and expanded internal and external resources (bB), the perception of stressors (C) and the reappraisal of the situation (cC), the coping strategies used (BC) as well as the outcomes of individual and family adaptation (xX) (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983). The child’s diagnosis and his/her difficulties are generally identified as the initials stressors (A) and the pileup of demands and stressors (aA) faced by mothers are often only documented with a global score, without specifying their individual contribution (Manning et al., 2011; McStay et al., 2014; Meleady et al., 2020; Pakenham et al., 2005; Paynter et al., 2013), or are not documented (Pozo et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2015). These studies also tend to look at the family’s resource through the lens of social (Meleady et al., 2020; Pakenham et al., 2005; Pozo et al., 2014) and formal support (e.g., professional and school services, Manning et al., 2011; Meleady et al., 2020). Thus, this model mainly focuses on the context of autism rather than on the overall experience of mothers’ adaptation in their various spheres of life. Furthermore, little attention is also paid in this model to the mothers’ perspective of their adaptation process as a whole.

Although this model identifies contributing elements to the adaptation of mothers of autistic children and illustrates the complexity of this process (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983), there is still an important gap in knowledge about the overall adaptation process of mothers of autistic children and how they perceive it. In fact, the broader context of motherhood is often overlooked in favor of a single focus on mothers’ experience of autism. Additionally, while many quantitative studies on the adaptation process of mothers of autistic children are available (Manning et al., 2011; McStay et al., 2014; Meleady et al., 2020; Pakenham et al., 2005; Paynter et al., 2013; Pozo et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2015), few qualitative studies have documented their perception of this process using a theoretical adaptation framework (Lutz et al., 2012). Yet, it is essential to consider the overall experience and perception of mothers of autistic children to fully understand the depth of their reality and to provide services that are genuinely suitable (des Rivières-Pigeon & Courcy, 2014; McCauley et al., 2019). Moreover, during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, mothers of autistic children faced several changes that increased their stressors and limited their access to resources (e.g., loss of childcare and specialized services, reduced access to support networks, increased child behavior problems, changes in routine, remote working, etc.). While these changes were associated with negatives impacts for some mothers of autistic children (Asbury et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021), they were associated with both positive and negative outcomes for others (Asbury et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al. 2021). Tokatly Latzer and colleagues (2021) suggest in their qualitative study that parents of autistic children’s appraisal of their situation during the COVID-19 lockdown closely influenced their outcome during this period. As such, it is crucial to document mothers of autistic children’s perception of their adaptation to better understand how their maternal adaptation process unfolds.

Therefore, this study aims to document the perception of mothers of young autistic children of their overall process of maternal adaptation. By doing so, the study will extend previous research by providing a broader and deeper perspective on what is already known about maternal adaptation in the context of autism. Thus, the present study aims to answer the following questions: (1) From the point of view of mothers of young autistic children, how do stressors and facilitators (resources, coping strategies and facilitating contexts) present in their environment influence their adaptation across the psychological, social, professional, marital, and parental life domains? (2) How do mothers of young autistic children perceive the outcomes of their process of maternal adaptation? The study uses a qualitative research design and an interpretative descriptive approach, which aims to describe and understand a phenomenon linked to the human experience, its components as well as their interrelations while considering the experiences and perception of the individuals involved (Gallagher & Marceau, 2020).

Method

Participants

The sample includes 17 French-speaking mothers of autistic children recruited in the province of Quebec (Canada) through social media and childcare services in the spring of 2020, using a purposeful sampling method. Participants took part in a larger research project led by Bussières and colleagues on the adaptation, parental stress, and sensitivity of mothers of autistic children (CER-18-252-07.27). The present study examines the point of view of mothers of young autistic children on their adaptation and it was part of a larger research using standardized instruments validated for preschoolers. Consequently, to participate, all mothers had to have at least one child between the ages of two and five years old diagnosed with autism or with a high probability of receiving such a diagnosis (i.e., family history of autism and children currently being evaluated or awaiting evaluation). However, due to challenges faced in recruitment, inclusion criteria were later extended to autistic children up to eight years old. Upon completing data collection, participants received a $25 gift card from a bookstore chain. We conducted recruitment for the present study until qualitative interviews with new participants provided little new information (saturation criteria, Guest et al., 2016; Pires, 1997). Diverse profiles were obtained within the sample with regards to family composition, severity of autistic features, place of residence, annual income, and mother’s employment status (see Table 1). The mothers were on average 36.7 years old (SD = 4.2) and their autistic children targeted by the study were 5.2 years old (SD = 1.1). Seventy-two percent (n = 13) of autistic children were boys and 89% had an official diagnosis of autism (n = 16). Seventy-seven percent of mothers were still with the father of the child (n = 13) and 88% had more than one child (n = 15). Regarding ethnicity, 94% of mothers were white Canadian (n = 16) and one was white French (5.9%). Eighty-nine percent of children were also white Canadian (n = 16) and eleven percent were of mix ethnicity (n = 2).

Procedure

The first author, a 3rd year Ph.D. candidate in psychology with clinical experience with autistic adults and children and their families, presented the study over the phone to the mothers who had responded to the call for participants. Their consent was electronically collected. Participants then completed a socio-demographic questionnaire and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale, 2nd edition (CARS2) (Schopler et al., 2010). An interview on mothers’ perceptions of their adaptation was then conducted by the first author. At another moment chosen by the participant, an interview on the characteristics of the child’s autism was conducted by a 2nd-year professional doctorate candidate in psychology with clinical experience with autistic children, supervised by a researcher and psychologist working in autism. Both interviews were recorded and conducted on the phone within a maximum interval of two weeks. All the data were collected between April and June 2020, during the first COVID-19 lockdown and in the month following its end.

Instruments

Autism Spectrum Characteristics

The CARS2 is a standardized instrument comprising a questionnaire for parents (CARS2-QPC) and a clinical evaluation grid (standard version, CARS2-ST) that makes it possible to document the presence, intensity, and duration of behaviors associated with autism in children two years of age and older (Schopler et al., 2010). We conducted a phone interview, developed by the research team, to gather more information on the child’s autism characteristics. The CARS2-ST was completed by the main author and a research assistant using the CARS2-QPC and the interviews. A two-way mixed, consistency, average-measures intra-class correlations (ICC = 0.86) conducted for ten CARS2-ST (58.8%, n = 17) suggests excellent inter-rater agreement (Cicchetti, 1994).

Mothers’ Adaptation

We developed a semi-structured interview canvas, based on extant research, consisting of seven questions and prompts on the mothers’ perception of their adaptation and the successes and challenges encountered as mothers of their autistic child (Interview canvas available as supplementary material). A question on their adaptation to the pandemic was also included to account for this unique period and how it might influence participant’s vision of their general maternal adaptation. An iterative approach (Miles et al., 2020) was used, meaning that small adjustments were made to the canvas as more data were collected and analyzed. To enable the participants to discuss their experiences with both autism and motherhood in general, we chose not to mention the autism diagnosis in the questions. The use of interviews is particularly relevant to understand and describe the experience of parents of an autistic child, since it allows researchers to be in more direct contact with the participants, while allowing them to express themselves more freely on the topics that are central to their experience (Cridland et al., 2015). The interviews were conducted over the phone (40 to 125 min, average of 67 min) and recorded.

Method of Analysis

Two undergraduates transcribed the interviews on maternal adaptation. The first author then verified for accuracy using the audio recording and field notes taken during and after each interview and performed repeated readings of the transcript, allowing familiarization with the data. She conducted a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) using a mixed inductive and deductive coding tree (Miles et al., 2020) based on the theoretical adaptation framework. Thus, an initial list of codes based on stressors, facilitators, and outcomes described in the literature was created, to which data-driven codes were then added during the codification process. A cross-case analysis was then performed on the entire data corpus to identify and describe the themes and subthemes linked to the experience of maternal adaptation and their interrelations (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Deslauriers, 1991). For example, the theme Colossal workload was derived from the subthemes: (1) Mental load, (2) “Trying to understand” the child, (3) “I must always be present”, (4) Planning interventions and preventing difficulties and (5) Implementing interventions with the child. Nvivo 13 software was used to facilitate coding and analysis.

To ensure trustworthiness meetings between three of the authors were conducted regularly to identify the central elements of the participants’ experience and to counter-validate and deepen the analysis as well as to discuss the interpretation and contextualization of the findings. This was done to reduce the risk of bias. In a process inspired by member checking (Hays & McKibben, 2021), a co-author with no involvement in data collection or analysis then reviewed and discussed the results based on her experience as a mother of two autistic adolescents. Results were then presented to and discussed with parents of autistic children during a poster presentation at a conference (Authors, 2022). Feedback received was used to reflect more deeply on our positionality and possible biases as clinicians and researchers. This reflection was then considered while interpreting the findings and identifying clinical implications, to ensure that they accurately represented the participants’ points of view. Meetings with a peer debriefer were conducted to review the final themes and findings, a technique that, according to many authors, contributes to enhancing the trustworthiness and credibility of studies (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Spall, 1998).

Positionality

As authors, we shared various experiences with autism and parenting, which allowed us to bring together multiple perspectives on the data and findings throughout the research process. Indeed, the team included researchers with and without clinical, personal, and research experience in autism. Regarding parenting, five of the seven authors are parents themselves (four mothers and one father), and all the authors have previous research and clinical experience in child development and/or parenting. Furthermore, one author is a mother of two autistic adolescents, one has clinical experience with autistic adults and families with young autistic children, and three authors had previous research experience with this population. All authors lean toward the social model of autism, which recognizes autism as both a difference and disability and emphasizes the distinction between social barriers and impairments (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021). Throughout the study, three co-authors regularly discussed their reactions to the material during meetings and the first author wrote about her feelings, thoughts, and biases in reflexive research journals to help us explore and reflect on our individual and shared positionality (Rodwell, 1998).

Results

The analyses revealed the complexity of the adaptation process experienced by mothers of a young autistic child. Indeed, mothers of autistic children identify many stressors, coping strategies, resources, facilitating contexts, and outcomes of this process in the psychological, social, professional, marital, and parental life domains. These stressors, facilitators, and outcomes, described by participants as overlapping and sharing intricate links, are presented in the next paragraphs following a chronological structure from the past to the present day

Becoming a mother: “Taming” the gap between expectations, reference models and reality

For many first-time mothers among the participants, becoming a parent (stressor, parental domain) turned out to be a major challenge, and for some, regardless of the neurodevelopmental condition of the child: “So, I would say that it was worse for me to just adapt to his arrival [as] a baby than to adapt to the fact that he functions differently” (Alex’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). Mothers explained this in part by the intensity of this period full of changes, novelty, and unknowns. Although they described varied experiences of motherhood, many agreed that there was a significant gap between their actual experience and their expectations on how it would be. Indeed, being a mother turned out to be much more difficult than they had thought. One stay-at-home mother of two autistic children explained: “That’s not how I saw […] motherhood. I love my children, I spend beautiful moments with them, but uh, it’s very demanding” (Jane’s mother, girl, moderate autistic traits).

However, many mothers also perceived that their child’s differences brought about additional challenges for their motherhood. For example, some reported that these characteristics had widened the gap between their reality and the normative reference models (stressor, parental domain) leading to feelings of invalidation and insecurity. One separated mother explained:

[As a baby, when Arlo slept,] he always put a blanket in his face, y’know for a new mother with the “Tiny Tot to Toddler”, y’know, that book [given by the hospital at the birth of the child], there must be nothing in his face. Well, if you took the blanket away from him, he would start screaming, y’know […]. (Arlo’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits)

For some, the difficulty arose from the fact that it took them several years to recognize their child’s differences (stressor, parental domain) and, consequently, to understand the challenges they faced. This proved challenging, as they tended to blame their parenting skills. One single mother explained: “Before knowing […] that Anna was autistic, I would say to myself: come on, I am such a bad mother […]” (Anna’s mother, girl, moderate autistic traits). Some shared that they believe their adaptation would have been easier if they had recognized their child’s differences earlier (facilitator, parental domain). One single mother explained: “[…] if I had known when he was 9-10 months, a year old, y’know, maybe that would have made things a lot easier […]” (Liam’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits). Mothers who identified these differences early reported that they were able to swiftly free themselves from the pressure of developmental norms, employ appropriate interventions, and, above all, undergo a single, smoother transition to motherhood, facilitating their adaptation. One separated mother explained: “I didn’t have time to adapt to my life as a mother before the diagnosis, that’s why, maybe, I’m less disturbed. […] I didn’t have time to be the mother of a child, and then realize he was autistic.” (Arlo’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). These women, however, often had difficulty getting others to recognize their child’s differences, including their spouse, which created conflicts and forced them to bear a large part of the evaluation process.

Diagnosis and Services: Stressors and Facilitators of Adaptation

In this regard, most mothers described the period of child evaluation (stressor, parental domain) as being very stressful (outcome, parental domain) and demanding because of the steps to be taken to obtain an evaluation, the numerous appointments, the emphasis placed on the difficulties of the child, and the uncertainty surrounding this long process. One stay-at-home mother explained:

[…] it was difficult to ask for services, to fight for services. Finally, having to go to the private sector. Then […] well going through a process of questions, of stress also of: ‘What are they going to tell me? Am I putting out all this money to be told: Well, there’s nothing wrong with him?’ (Thomas’ mother, boy, moderate autistic traits)

Obtaining the diagnosis (Stressor and facilitator parental domain) was met with ambivalence by most mothers. Indeed, many expressed experiencing shock, sadness (outcomes, parental domain), and worries about their child’s future. However, these women also reported regaining their self-confidence and feeling relieved at the prospect of receiving support and of being able to better understand their child and the challenges they faced (feeling competent, outcome, parental domain):

[Before it was] as if we were climbing blindly […], to have arrived at the diagnosis [of Leo and his father] it means that now we see a little better, y’know, we look at the wall to climb, and we see the grips a little better, and we can better analyze and then plan our way. […] it’s more peaceful, now I would say. (Leo’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits)

Establishing services (Stressor and facilitator parental domain) for the child was then a period that called upon the mothers’ adaptation skills just as much. They explained that access to services was difficult (e.g., long waiting lists and hard-to-find services) and that they had met practitioners with little knowledge of autism or who made harsh judgments about them. Many reported they had to “fight” (Carl’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits) or go to the private sector to obtain quality services. Because of the large investment of time, energy, and money required, mothers sometimes felt limited in their ability to offer their child all the services she/he needed, which generated feelings of guilt and helplessness (outcome, parental domain). These services also imposed a heavy workload (e.g., communicating with professionals and implementing recommendations) that fell largely on the shoulders of already exhausted and overburdened mothers:

[…] I realized with the lockdown […] the weight of the appointments […] I didn’t want to see it because I would say to myself: ‘Well these appointments, they’re helping him.’ But since we no longer have appointments, I can see that it has really relieved our stress, our family organization. (Luca’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits)

In short, on the one hand, mothers perceived services as being a facilitator of their adaptation, since they promote the development of their child and help them to feel supported and better equipped. On the other hand, the vast majority of mothers described services as a major source of stress that fueled their parenting stress, fatigue and feelings of disappointment, guilt, helplessness, frustration (outcome, parental domain), and incompetence (outcome, parental domain).

We went to see the occupational therapist, then saw her again two weeks later and: ‘Have you practiced this exercise?’ ‘We put the list on our fridge, but we didn’t do anything ‘. In addition to feeling overwhelmed, well, we feel inadequate because we should have done better, we should have done more. (Luca’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits)

On a daily basis, stressors accumulate and impact various life domains

Parental responsibilities

Regarding daily life, the child’s difficulties (stressor, parental domains) occupied a prominent place in the current lives of mothers and represented a major stressor. Indeed, all the autistic children in the study faced adaptive challenges throughout their development, including internalized, externalized, or developmental problems. Many also experienced frequent meltdowns and issues on the following levels: social, sensory, communication, sleep, learning, eating, and/or integration in daycare or school, which could be aggravated during periods of transition.

For all the participants, the child’s difficulties caused constant worry and a colossal workload (stressor, parental domain). In fact, the caregiving and educational tasks became more complex since energy-consuming, invasive, and stressful reflective work was required to understand the child’s needs, plan interventions, and identify the contexts that likely contributed to the occurrence of difficulties. Some mothers mentioned having to maintain a state of hypervigilance at all times in order to ensure the physical safety of their child or to prevent problems. Many also reported living in constant anticipation of potential difficulties arising: “Every day […] the school would call me: ‘Thomas is in meltdown. You have to come.’ […] The night goes on, and you have trouble sleeping because you know that the next day it will be the same thing.” (Thomas’ mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). Moreover, some mothers explained that their child’s difficulties increased some pre-existing difficulties related to personal conditions (e.g., autism or anxiety) or traits (e.g., perfectionism; stressor, psychological domain), which in turn could make them more reactive to their child’s behaviors: “[my children] are quite something on a noise level. And I have issues on a sensory level, and I find it difficult to handle shouting and sudden noise, so my main challenge is managing my sensory overload.” (Loic and Charles’ mother, boys, moderate autistic traits, and NA).

To prevent and manage their child’s difficulties as well as support his development, mothers mentioned implementing a variety of intervention strategies. However, many reported experiencing little success with them. They added that the interventions that worked often went against the usual standards or required rigor and great self -control on their part. For these reasons, mothers could not succeed in constantly applying these interventions and sometimes had the impression that they could not play their maternal role as they would have liked. One stay-at- home mother of two autistic children explained: “[…] I sometimes have the impression that I have to be more of a therapist than a mother, y’know. […] this is not the role I wanted.” (Jane’s mother, girl, moderate autistic traits). In addition, certain interventions, such as the use of physical force, were described as demanding, presenting risks and serious issues: “[…] it goes against our values too. Y’know I, I would not be surprised one day, to be reported to Child Protection Services. Because sometimes I have to restrain her […]” (Zoey’s mother, girl, moderate autistic traits). Intervening with the child is therefore demanding, stressful, and not very rewarding for mothers.

For many mothers, in addition to these challenges, there was significant pressure (stressor, parental domain) to be the one ensuring the proper development of the child. This pressure stemmed from their personal expectations, those of professionals, and the message they conveyed regarding the importance of early intervention. Mothers reported that it was difficult, if not impossible, to meet these expectations. One mother receiving public services for her son and working part time stated: “It’s the constant impression of having to do more, and not being able to deliver. Y’know, the energy. The time. Or just the motivation.” (Luca’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits). Many added that due to the unique behaviors or needs of the child, it was nearly impossible for someone else to occasionally take over.

Thus, the majority of mothers reported that their parental responsibilities with the autistic child and the challenges encountered had the effect of reducing their feeling of competence and generating a high level of parental stress and fatigue. They reported that these challenges made them experience feelings of guilt, frustration, helplessness, and failure. Their parental responsibilities thus took up all the space in their lives, leaving them very little to invest in other life domains. In this sense, we have observed in the context of the interviews that many mothers tended to talk more about the adaptation of their child or the way in which they learned to meet their child’s needs rather than about their own adaptation process. One single mother made the observation several times: “Ah, I’m still talking about Liam, I no longer talk about myself” (Liam’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits). Similarly, many mothers pointed out that they lack the time to use the support services offered to them (e.g., therapy and parents’ groups; facilitator, psychological domain), despite recognizing their benefits.

Concerns About the Future

The parental stress of most mothers was exacerbated by the uncertainty surrounding the future (stressor, parental domain) of their child, which served as a major source of daily worries: “Is he going to be violent later? Are we going to be able to handle him all the time? […] And we’re going to grow old too. […] What will happen if we die?” (Max’s mother, boy, severe autistic traits). The daily anguish stemming from these worries prompted some mothers of children presenting severe traits of autism to plan for their child’s future (e.g., investing money, planning to retire early, or raising awareness; facilitator, parental domain), which was reassuring, yet demanding.

The Quality of the Relationship with the Child

Furthermore, some participants added that their child’s communication difficulties or their lack of demonstrations of affection towards them could also prevent them from interacting with their child as they would have liked (stressor, parental domain), which was a source of disappointment and sadness: “I would like to be able to talk to him, for him to tell me about his day […] If only how he feels. […] I find it super hard.” (Carl’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). Conversely, many mothers underlined that exchange of affection with their child and their good relationship (facilitator, parental domain) with him/her were important facilitators since this brought them happiness, soothed them, and gave them strength.

Juggling with the Child, Work and Family Demands

In addition to caring for the autistic child, most mothers underlined that having to take care of other members of their family, to assume a major part of the domestic and family organization tasks, and to maintain their performance at work represented major stressors in their daily lives. They described balancing these different responsibilities as difficult (work-family balance, stressor, professional domain) and having a significant impact on their work commitments (outcome, professional domain). One mother working full time and whose partner is a stay-at-home dad explained: “I have trouble getting through my job, that’s another stress.” (Max’s mother, boy, severe autistic traits). Some chose or were forced to make changes to facilitate this balance (Stressor and facilitator professional domain). Nevertheless, they explained that these changes could also: (1) be a source of stress: “[…] it is an economic stress. […]” (Max’s mother, boy, severe autistic traits); (2) represent certain sacrifices: “[…] I could perhaps have advanced in my career, and then it was like put on ‘hold’ for a few years.” (Zack’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits, blended family); or (3) create an imbalance in the division of tasks in the couple: “[…] it falls on my shoulders for the medical or psychological side, and so forth. […] I am a stay-at-home mom, so it’s obvious that it’s much more my job. So, often it’s a lot.” (Thomas’ mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). Nevertheless, some mothers underlined that what they had learned in their role as a mother allowed professional development (outcome, professional domain). A single mother explained: “Because all the expertise that I acquire with my son […] I find that as a social practitioner it gives me that experience.” (Liam’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits).

Marital Life: The Importance of Support and the Impacts on the Couple

Many mothers explained that the support of their current spouse or the father of the autistic child (facilitator, marital domain) was an important facilitator. In fact, many explained that maintaining good communication made it possible to defuse conflicts, while the sense of being part of a team allowed them to feel supported and to take a breather when they needed it: “[…] [the children’s father] is very, very present and it’s helpful both as a parent and as a mother to have support too.” (Zoey’s mother, girl, moderate autistic traits). Moreover, some mothers reported having succeeded in maintaining a stable couple (outcome, marital domain) despite the challenges encountered, and that sometimes even, these had allowed them to strengthen their bond (outcome, marital domain). One autistic mother whose partner is also autistic explained: “It made us bond, it really united us […] the ordeals […]” (Loic and Charles’ mother, boys, moderate autistic traits and NA). However, this reality was not shared by the majority and many said they had the impression of taking on alone a large part of the domestic and educational tasks, which could contribute to their weariness. In fact, most women reported that the arrival of the autistic child, through the associated stressors, had negative impacts on their marital life (outcome, marital domain). Many said they experienced more conflicts because of the differences in their vision (stressor, marital domain) of autism and felt they had little availability for their spouse because of their lack of personal space (outcome, psychological domain): “Everything, everything, everything revolves around the children’s needs, so that we get no time alone or together. So, it really has a negative impact. […] it’s a crisis situation right now.” (Juliet’s mother, girl, severe autistic traits).

Social Life: Stressors and Outcomes

On the social level, many mothers said they encountered social barriers (stressor, social domain) that led them to feel isolated and have a less satisfying social life (outcome, social domain) than in the past. For example, many shared that they lost friends and that it was now more difficult for them to participate in social events due to the autistic child’s behaviors, lack of understanding of others (stressor, social domain), and fatigue: “[…] it’s complicated to go out with the two children. We’re already exhausted. It’s as if social outings have become like a burden.” (Luca’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits). Conversely, some mothers underlined that social support (facilitator, social domain) and interacting with others living similar situations helped to break their isolation and facilitate their adaptation. Many mentioned that the efforts invested in adapting moments spent with others (e.g., spending less time at events) and maintaining their friendships (facilitator, social domain) had enabled them to maintain a satisfying social life (outcome, social domain) despite the challenges faced. The same applied to the openness and kindness of their friends and family and the accessibility to respite opportunities (facilitator, parental domain). One single mother explained: “[…] my mother also looked after my son a lot, so my mother allowed me a lot to […] be able to continue to have a social life.” (Liam’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits). Moreover, the involvement of grandparents with the child, for appointments, financial support or domestic assistance, represented an important facilitator for mothers’ adaptation.

The Relationship with Society: A Major Stressor

In addition, many mothers expressed concerns about how their peers perceived their child and their parenting skills, and they also shared the distress caused by the judgments (stressor, social domain) they felt directed towards them. Several mothers of children with minimal to moderate autism traits shared having already received derogatory comments or invalidating advice from relatives and strangers: “Y’know, there was once a lady who said to me: My God, they’re not able to raise their child.” (Carl’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). Some participants mentioned that the population’s lack of knowledge about autism and their reality seemed to exacerbate the judgments mothers faced, leading them to feel misunderstood: “It’s a reality that’s difficult to grasp for people who don’t live it. And I, I suffered a lot from that. Because people thought we were exaggerating and that we were too stressed.” (Loic and Charles’ mother, boys, moderate autistic traits and NA).

In short, the analyses showed that that not all mothers had support from their spouse, family, and friends; many had support from only one of these sources. It is also important to underline that almost all the reported stressors were found, to varying degrees, in the narratives of each of the participants, indicating that they faced an significant accumulation of stressors daily in all life domains. Faced with this accumulation, mothers explained that they used various adaptation strategies in an attempt to maintain a certain balance in life.

Adaptation Strategies Used by Mothers

To avoid certain disappointments, to alleviate the pressure on their shoulders, and to enhance self-protection, many mothers explained that they worked on reducing their expectations, respecting their personal limits, and letting go of certain responsibilities (facilitator, parental domain). However, they pointed out that they might feel guilty for doing so:

[…] sometimes, I don’t find myself to be the perfect mom because I don’t do [all the exercises] but […] I’m a single mom, I say to myself: Look, let’s calm down, we do what we can, we only have 24 h. (Liam’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits)

In addition, many mothers used reframing strategies (facilitator, parental domain), aimed at qualifying their experience or changing their perception of stressors. For example, they reported using humor, focusing on the positive, looking at the facts or comparing themselves to peers: “[…] I have a friend who has a severely disabled child. And, y’know, there’s no attachment bond, the child is no longer progressing […] I say to myself: I still have more […]” (Rose’s mother, girl, severe autistic traits).

Similarly, many mothers indicated redirecting their attention to the present (facilitator, parental domain), the progress of the child, and the little moments of daily happiness in order to avoid dwelling on the future. They mentioned that the progress of the child and the shared quality moments were sources of happiness and pride (outcome, parental domain), reassuring them about the future and their parenting skills, and giving meaning to their efforts: “[…] having little moments of happiness that are always accessible: like reading a book close together […] It’s a way for me to re-energize.” (Thomas’ mother, boy, moderate autistic traits).

Finally, most mothers explained that to preserve their balance and their ability to take care of their family, it was essential to take time for themselves (facilitator, psychological domain) to meet their needs, ranging from basic necessities to personal fulfillment. They did so by going to bed earlier, exercising, pursuing meaningful personal projects (e.g., going to school or having a business), or taking time to eat. Many mothers, however, mentioned that they had difficulty taking this time for themselves as they had to attend to several other responsibilities. One autistic mother whose partner is also autistic explained: “[…] it’s not easy to do because it also brings its share of guilt. But it’s necessary for the family to remain steadfast.” (Loic and Charles’ mother, boys, moderate autistic traits and NA).

In summary, it was observed that mothers had access to different numbers and types of facilitators (i.e., adaptation strategies and resources). In fact, mothers viewed several of the resources that favored their adaptation as not very accessible, and found several adaptation strategies to be difficult to set up.

Various Outcomes of the Adaptation Process

The adaptation process of these women, marked by multiple stressors and hard-to-access facilitators, gave rise to a variety of outcomes, as presented in the previous pages for the social, professional, marital, and parental life domains (see Table 2 for a summary).

Mothers’ perceptions of their adaptation can be placed on a continuum ranging from severe difficulties of adaptation to positive adaptation, where each mother evolved at her own pace and differently from one domain to another. Nevertheless, it was observed that all the mothers reported experiencing distress or adaptation difficulties in one or more life domains at the time of the interview. On a psychological level, almost all mothers reported experiencing daily a high level of physical and mental fatigue (outcome, psychological domain). In addition, more than half of the participants had experienced at least one episode during which they faced mental health difficulties (e.g., depression, anxiety, adaptation disorder, burnout or postpartum depression; outcome, psychological domain) impacting their functioning, necessitating a sick leave and/or medication. One full time working mother explained:

[…] I had to get medical help, uh, because, uh, I was, I had become very, very irritable, I had become overwhelmed with everything. […] I was a good 50% less functional. […] I had become too anxious whereas y’know, uh, that’s not me, I’m not anxious in life. (Rose’s mother, girl, severe autistic traits)

Nevertheless, many participants also underlined that their experience of motherhood led them to develop on a personal level (outcome, psychological domain). A separated mother explained: “And it may have made me evolve as a human being. […] I would say that I learn to know myself better, respect myself better, better define my limits to myself.” (Arlo’s mother, boy, moderate autistic traits). They added that motherhood brought them happiness, despite the challenges encountered. One single mother explained: “I am happier now in my life than I was when I had, at other times, when I had all my freedom […]” (Liam’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits).

Regarding the overall perception of their adaptation, the collected narratives of the mothers were nuanced and varied. On the one hand, nearly half of the mothers described having a difficult adaptation, that is, struggling to meet their daily needs and “[…] trying to survive […]” (Max’s mother, boy, severe autistic traits). However, many explained that the passage of time and the efforts invested in learning to set their limits and take care of themselves had recently started to help them to regain the upper hand over the stressors: “[…] I’m currently adapting, but on the right track […] before, everything used to come before me […] I’m not saying that my balance is perfect, I’m learning” (Hugo’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits). On the other hand, the second half of the mothers rather described their adaptation as quite good the extent of the challenges encountered. They explained, among other things, having managed to find a certain balance between their personal well-being and answering the child’s needs. Nevertheless, they emphasized that their adaptation remained variable with new challenges encountered:

But no, I think my well-being is still good. But y’know it’s sure that it’s normal life, we live under stress, we live some more fragile periods, huh, because sometimes behaviors relapse and all that, but roughly speaking I think we succeed in having a good balance. (Noah’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits)

Finally, it is relevant to underline that the narratives of several mothers suggest that there was a close relationship between their personal adaptation and that of their child. Indeed, many shared that their condition directly affected their child’s adaptation and vice versa: “Well, it’s sure that […] I’m fine when he’s fine and doing well” (Luca’s mother, boy, minimal autistic traits); “You know when I’m fine, when I’m rested, everyone is more available” (Juliet’s mother, girl, severe autistic traits).

Discussion

This study aimed to better understand the perceptions that mothers of young autistic children have of their overall process of adaptation across the psychological, social, professional, marital, and parental life domains. Many stressors, facilitators, and outcomes of this process identified in the study closely align with those documented in the literature. This is particularly the case for stressors such as mental and daily workload, uncertainty surrounding the future, and lack of understanding from others (Cardon & Marshall, 2021; Nicholas et al., 2016; Woodgate et al., 2008). The same is true for many of the facilitators identified, such as social and marital support, letting go or reframing strategies (Corcoran et al., 2015; Woodgate et al., 2008). Finally, several outcomes found in the literature were also reported by participants, such as psychological distress, fatigue, social isolation or stronger bond in the couple (Nealy et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2022).

How Stressors and Facilitators Present in the Environment Influence Maternal Adaptation

Before the Child is Diagnosed with Autism

This study also identified new findings regarding how stressors and facilitators present in the environment influence maternal adaptation in the context of autism. First, this study highlighted that the adaptation process begins well before the child receives his/her diagnosis, since stressors and facilitators are already at work at this time. Indeed, contrary to the double ABCX Model (Manning et al., 2011; McStay et al., 2014; Meleady et al., 2020; Paynter et al., 2013; Pozo et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2015)—which often identify the child’s diagnostic of autism as the initial stressors–, the participants’ narratives illustrate that it is rather the fact of “taming” the maternal role and welcoming a new child that triggers the process of maternal adaptation, even before most of the characteristics of autism are manifest in the child. While this period of transition to parenthood is widely documented as both a normal and stressful developmental phase in the general population (Nelson, 2003), there has been comparatively less attention to it in autism research to date.

In the same vein, the participants’ narratives also revealed that certain stressors and facilitators, acknowledged as influential in adaptation once the diagnosis of the child has been obtained, were already present beforehand. This is particularly the case of the stressor represented by the gap created by the child’s differences, the mother’s daily reality, her expectations, and the normative reference models (Cardon & Marshall, 2021; Corcoran et al., 2015; Dieleman et al., 2018; Nicholas et al., 2016). In fact, this gap seems to be perceived even more distressing by mothers before the child’s diagnosis is known since, as in its absence, they may tend to blame themselves for it. Several studies have emphasized the benefits of diagnosing autism at a young age to assist mothers in better understanding and supporting their child, thereby facilitating their personal adaptation (Cardon & Marshall, 2021; Dieleman et al., 2018). However, the results of the present study go beyond this observation by suggesting that recognition of the child’s differences can begin from the first months of the child’s life, without a formal diagnostic hypothesis necessarily being established. From this moment, it can play a role of facilitator of maternal adaptation.

The Main Source of Daily Stress for Mothers

To this day, adaptation models found in the autism literature, such as the double ABCX Model (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983) have identified as main stressors the severity of the child’s autism features and their co-occurring difficulties (Lutz et al., 2012; Manning et al., 2011; McStay et al., 2014; Meleady et al., 2020; Paynter et al., 2013; Pozo et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2015). This study highlights that autism features and the child’s difficulties are indeed a major source of stress as they exacerbate the stressors mothers of autistic children encounter in various life domains (e.g., mental and parental workload or conflicts in the couple). However, the participants’ narratives suggest that the relation between the severity of the child’s difficulties and the extent of the stressors encountered is complex and variable. For example, even though we can not say much about group differences, we notice that amongst our participants, mainly mothers of an autistic child with subtle autism characteristics described stigma and lack of understanding from others as a major stressor. Participants with a child with more important limitations on the functional level rather seems to emphasize as stressors the uncertainty regarding the future and the extent of their daily workload to meet the child’s needs. Thus, the most stressful aspect appears to be not necessarily the severity of the child’s difficulties per se, but rather how these difficulties integrate into the mothers’ lives.

Furthermore, our study emphasize that the main source of stress for mothers of young autistic children arises from the cumulative accumulation of stressors across various life domains. Indeed, it is difficult to isolate one or some specific stressors as being central to the process of maternal adaptation since the stressors are described as intertwined, such that stressors encountered in one sphere exacerbate those in other life domains, and that reducing one of the stressors has the potential to bring about a new one or exacerbate another. One example concerns the work-family balance: stress, fatigue, and the demands resulting respectively from professional and family responsibilities, mutually make it more difficult to fulfill the responsibilities of the other sphere. In addition, if mothers stop working to reduce or eliminate one of these stressors, financial stress is added (Nicholas et al., 2016). Thus, to fully understand the process of maternal adaptation, this study highlights the importance of taking into account all the stressors encountered by mothers in the different life domains as well as their accumulation, rather than emphasizing the child’s characteristics as the main stressor (Lutz et al., 2012; Manning et al., 2011; McStay et al., 2014; Meleady et al., 2020; Pakenham et al., 2005; Paynter et al., 2013; Pozo et al., 2014).

Imbalance between Stressors and Facilitators

This study also underlines that there is an imbalance between the stressors and the facilitators of the process of maternal adaptation, which could explain why the participants’ narratives all refer to at least one of the difficulties of adaptation found in the literature (Corcoran et al., 2015; des Rivières-Pigeon & Courcy, 2014; Nealy et al., 2012). We observed that mothers of autistic children encountered multiple stressors in each sphere of their lives, but in contrast had access to relatively few resources and adaptation strategies that would allow them to effectively reduce these stressors or counteract their impacts. Indeed, the results illustrate that certain facilitators are also a major source of stress. This is particularly the case of services for the child, which facilitate the adaptation of mothers of autistic children in the long term by providing them with tools and promoting the development of their child, but which are very demanding and stressful for them in the short term. Our findings regarding this ambivalence towards services corroborate prior suggestions in this regard (Cardon & Marshall, 2021; Jackson et al., 2020; Nicholas et al., 2016; Safe et al., 2012).

In addition, participants’ narratives also suggest that it is difficult to reduce the stressors encountered by mothers of autistic children. In fact, from their perspective, it is almost impossible to reduce their mental and parental workload since it is necessary to ensure the well-being of their child and reduce the occurrence of difficulties. This observation is in line with des Rivières-Pigeon and Courcy’s (2017) perspective, highlighting that mothers cannot avoid this workload since it is closely linked to the “basic dimensions of parental responsibilities, such as ensuring that the child is clean, fed and safe” (p.16). Thus, evading it could expose mothers and their autistic children to important negative consequences, potentially extending to legal repercussions (des Rivières-Pigeon & Courcy, 2017). Yet, participants reported receiving little help with this workload, which is more demanding than that of parents in the general population. Indeed, although several studies document the importance of social and marital support as well as respite for maternal adaptation (Safe et al., 2012; Woodgate et al., 2008), participants reported having very little access to these resources. In addition, participants underlined that because of the extent of the stressors encountered, it was very difficult for them to take time for themselves or consult professional resources for themselves, which is in line with other studies (Dieleman et al., 2018; McAuliffe et al., 2022; Woodgate et al., 2008). Accordingly, this leads to difficulties in meeting their own needs or the demands of other life domains.

Mothers’ Perception of the Outcomes of Their Adaptation Process

This study also underlines the complexity of the maternal adaptation process by highlighting the variability of the outcomes reported by the participants. Their narratives illustrate outcomes that are multilayers and vary from one mother to another and from one sphere to another. Indeed, whereas some mothers only reported outcomes of adaptation difficulties, others described outcomes of good adaptation for certain life domains (e.g., she is adapting fairly well in the social, parental, and professional life domains) and outcomes of difficulties of adaptation for other life domains (e.g., She at the same time present marked adaptation difficulties in the marital and psychological life domains). In addition, the results also suggest that in the mothers’ perspective, their adaptation is closely linked to their child’s adaptation and that it is constantly evolving, and therefore, subject to many changes over time. This finding is in line with what was put forward by Lutz and his colleagues (2012).

Implications for Research

As the present study suggests that maternal adaptation in the context of autism is multi-determined by stressors and facilitators from various life domains, similarly to how parenting behaviors are explained by Belsky’s classic parenting model (Belsky, 1984; Taraban & Shaw, 2018), future research should investigate further how various stressors interact and how a combination of facilitators could counteract the impacts of such accumulation of stressors. Thus, more variables beyond the child’s characteristics and autism traits should be included in research designs as predictors of maternal adaptation. Additionally, considering the complexity of the adaptation process of mothers of a young autistic child and the variability of the resulting outcomes, future studies should attempt to identify the different adaptation trajectories taken by mothers of autistic children in order to target specific strategies to support them according to how their adaptation fluctuates over time.

Clinical Implications

On a clinical level, this study yields four important observations. First, it seems essential to raise awareness on the challenges as well as the potential strengths of raising a child with autism, so that mothers of autistic children feel better understood and supported, and that they are the target of less judgment. It seems crucial that awareness-raising efforts cover the entire spectrum of autism, since the mothers whose child presents less visible characteristics of autism report suffering a lot from other people’s judgments and lack of understanding. Second, supporting mothers of autistic children in the early recognition of their child’s differences as well as offering them reference models of child development and motherhood in the context of autism may facilitate their adaptation. To do this, books, websites, and mobile applications on motherhood and child developmental milestones could for example include more information and examples on neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g., autism) within the sections intended for the general population. This would make such information more accessible to mothers who do not yet suspect that their child is autistic and could thereby facilitate early recognition of certain differences in the child and normalize their experience. Moreover, this could indirectly inform the general population about autism and certain aspects of the reality of mothers (and fathers) of young autistic children, thus breaking their isolation and raising awareness of the challenges they face (Anthony et al., 2020; Zaki & Moawad, 2016). Third, it seems important to revise the structure of intervention services to better take into account the reality of mothers of autistic children (Galpin et al., 2018). Indeed, it is clear that current services are centered on the needs of the autistic child and take little account of the accumulation of stressors and mothers’ needs. Considering that maternal adaptation influences mothers’ ability to take care of their child and implement the recommended interventions (Estes et al., 2019), and that offering parents services that promote their well-being and mental health also contributes to supporting their child’s adaptation and development (Cachia et al., 2016), it seems relevant that service providers should promote a better balance between the child’s adaptation and that of the mother, such as by adopting a family-centered care approach. This implies adjusting the involvement asked of mothers in the intervention program of their child according to their reality (e.g., simplifying exercises to be done at home and reducing their frequency or offering services to autistic children in their home or childcare environment to limit travel) as a way of reducing their feelings of guilt and their burden (Galpin et al., 2018). Similarly, services intended for mothers would benefit from being offered at the same time and in the same location as services intended for the child or even offering drop-in daycare to facilitate their access and allow mothers to take time to tend to their personal needs. Fourth, it seems essential to provide parents with practical help and resources that may help to actually buffer stress (e.g., respite care, help in cooking and cleaning, child transportation to appointments, etc.) rather than working on reducing stressors since, in the mothers’ perspective, reducing stressors turns out to be almost impossible and sometimes even more stressful. It takes a village - not only interventions’ programs - to raise an autistic child.

Limitations

This study nevertheless has certain limitations. First, as the notion of adaptation is broad and frequently used in popular discourse for different purposes, several participants had difficulty understanding the meaning of one of the questions (“In general, how would you describe your adaptation as the mother of (child’s name)?”). Some mothers focused on describing how they managed to meet their child’s needs, rather than describing their personal adaptation as defined in the article, which might have been addressed by piloting the interview protocol prior to data collection and adding a brief description of the notion of adaptation. However, this could also be explained by the “mask of motherhood” (Maushart, 1997), that is, a tendency for mothers to speak little about their experiences and their negative emotions in order to project an image more in keeping with the commonly accepted image of motherhood (Gill & Liamputtong, 2011). A few participants also pointed out that they were not used to talking about themselves and that it was much easier to talk about their child. Second, due to logistical and time constraints, member checking could not be conducted. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, phone interviews were used instead of face-to-face, limiting access to non-verbal information, which may have impacted how interviews were conducted and data was coded. However, it also offers greater flexibility to the participants to accommodate their reality (e.g., being outside during the interview to avoid being distracted by their children). Finally, although efforts were made to obtain a diversified sample of mothers, the sample has a high level of education (88.2% of participants had completed at least an undergraduate education compared to 36.7% in the general population in Quebec; Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2020). It is therefore possible that the women who participated in the study had access to more resources that could promote their adaptation than their peers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study illuminated the overall adaptation process of mothers of a young autistic child by delving into their perceptions of the stressors, facilitators, and outcomes associated with this journey. It has provided a nuanced understanding of the complexity of this process, which commences from the birth of the child and is marked by intersecting stressors, facilitators, and outcomes across the different domains of mothers’ lives. Furthermore, the study revealed complex interrelations between maternal adaptation and adaptation of the child. Consequently, this study highlights the significance of examining the entire life context of mothers with a young autistic child to better comprehend the complex dynamics shaping their maternal adaptation process. This more ‘holistic’ understanding can enhance the tailoring of services for both the mothers and their children.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available since they contain information that could compromise research participants’ privacy and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and obtention of ethical approval.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Anthony, B. J., Robertson, H. A., Verbalis, A., Myrick, Y., Troxel, M., Seese, S., & Anthony, L. G. (2020). Increasing autism acceptance: The impact of the Sesame Street “See amazing in all children” initiative. Autism, 24(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319847927.

Asbury, K., Fox, L., Deniz, E., Code, A., & Toseeb, U. (2021). How is COVID-19 affecting the mental health of children with special educational needs and disabilities and their families? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(5), 1772–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04577-2.

Authors. (2022). Mothers’ perspective on their adaptation in the context of child’s autism : The added layer of autism to their experience of motherhood [Poster presentation]. Montréal, Canada: SCERT’s 3rd annual Conference on Neurodevelopmental Conditions. October.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836.

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., & Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Cachia, R. L., Anderson, A., & Moore, D. W. (2016). Mindfulness, stress and well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0193-8.

Cardon, A., & Marshall, T. (2021). To raise a child with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative, comparative study of parental experiences in the United States and Senegal. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(3), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461520953342.

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290.

Corcoran, J., Berry, A., & Hill, S. (2015). The lived experience of US parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629515577876.

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Caputi, P., & Magee, C. A. (2015). Qualitative research with families living with autism spectrum disorder: Recommendations for conducting semistructured interviews. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.964191.

Dalle Mese, D., & Tarquinio, C. (2012). Questions d’adaptation: Réflexions et ouvertures. L’adaptation entre psychologie, philosophie et neurosciences. In C. Tarquinio & E. Spitz (Eds.), Psychologie de l’adaptation (pp. 31–51). De Boeck.

Davy, G., Unwin, K. L., Barbaro, J., & Dissanayake, C. (2022). Leisure, employment, community participation and quality of life in caregivers of autistic children: A scoping review. Autism, 26(8), 1916–1930. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221105836.

De Clercq, L. E., Prinzie, P., Swerts, C., Ortibus, E., & De Pauw, S. S. (2022). “Tell me about your child, the relationship with your child and your parental experiences”: A qualitative study of spontaneous speech samples among parents raising a child with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder, Cerebral Palsy or Down Syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 34(2), 295–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-021-09800-1.

des Rivières-Pigeon, C., & Courcy, I. (2014). Autisme et TSA: Quelles réalités pour les parents au Québec?: Santé et bien-être des parents d’enfant ayant un trouble dans le spectre de l’autisme au Québec. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

des Rivières-Pigeon, C., & Courcy, I. (2017). « Il faut toujours être là. » Analyse du travail parental en contexte d’autisme. Enfances Familles Générations [Online], 28. http://journals.openedition.org/efg/1592.

Deslauriers, J.-P. (1991). Recherche qualitative : Guide pratique. McGraw-Hill. https://bac-lac.on.worldcat.org/oclc/977239910

Dieleman, L. M., Moyson, T., De Pauw, S. S., Prinzie, P., & Soenens, B. (2018). Parents’ need-related experiences and behaviors when raising a child with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 42, e26–e37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.06.005.

Estes, A., Olson, E., Sullivan, K., Greenson, J., Winter, J., Dawson, G., & Munson, J. (2013). Parenting-related stress and psychological distress in mothers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain and Development, 35(2), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2012.10.004.

Estes, A., Swain, D. M., & MacDuffie, K. E. (2019). The effects of early autism intervention on parents and family adaptive functioning. Pediatric Medicine, 2, 21 https://doi.org/10.21037/pm.2019.05.05.

Gallagher, F., & Marceau, M. (2020). La rechercher descriptive interprétative : Exploration du concept de la validité en tant qu’impératif social dans le contexte de l’évaluation des apprentissages en pédagogie des sciences de la santé. In M. Corbière & N. Larivière (Eds.), Méthodes qualitatives, quantitatives et mixtes : Dans la recherche en sciences humaines, sociales et de la santé (2e ed., pp. 5–32). Presses de l’Université du Québec. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1c29qz7.6

Galpin, J., Barratt, P., Ashcroft, E., Greathead, S., Kenny, L., & Pellicano, E. (2018). ‘The dots just don’t join up’: Understanding the support needs of families of children on the autism spectrum. Autism, 22(5), 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316687989.

Gill, J., & Liamputtong, P. (2011). Walk a mile in my shoes: Life as a mother of a child with Asperger’s Syndrome. Qualitative Social Work, 12(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325011415565.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2016). How many interviews are enough? Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05279903.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99, 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12365.

Institut de la statistique du Québec. (2020). Panorama des regions du Québec: Édition 2020. Gouvernement du Québec, Québec. https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/fichier/panorama-des-regions-du-quebec-edition-2020.pdf.

Jackson, L., Keville, S., & Ludlow, A. K. (2020). Mothers’ experiences of accessing mental health care for their child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 534–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01662-8.

Kütük, M. Ö., Tufan, A. E., Kılıçaslan, F., Güler, G., Çelik, F., Altıntaş, E., Gökçen, C., Karadağ, M., Yektaş, Ç., & Mutluer, T. (2021). High depression symptoms and burnout levels among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A multi-center, cross-sectional, case–control study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(11), 4086–4099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04874-4.

Lee, V., Albaum, C., Tablon Modica, P., Ahmad, F., Gorter, J. W., Khanlou, N., McMorris, C., Lai, J., Harrison, C., Hedley, T., Johnston, P., Putterman, C., Spoelstra, M., & Weiss, J. A. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on the mental health and wellbeing of caregivers of autistic children and youth: A scoping review. Autism Research, 14(12), 2477–2494. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2616.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturlalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lutz, H. R., Patterson, B. J., & Klein, J. (2012). Coping with autism: A journey toward adaptation. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27(3), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2011.03.013.

Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K. A., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Esler, A., Furnier, S. M., Hallas, L., Hall-Lande, J., & Hudson, A. (2021). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 70(11). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/ss7011a1.htm

Manning, M. M., Wainwright, L., & Bennett, J. (2011). The double ABCX model of adaptation in racially diverse families with a school-age child with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(3), 320–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1056-1.

Maushart, S. (1997). The mask of motherhood. How becoming a mother changes everything and why we pretend it doesn’t. Australia: Random House.

McAuliffe, T., Cordier, R., Chen, Y. W., Vaz, S., Thomas, Y., & Falkmer, T. (2022). In-the-moment experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder: a comparison by household status and region of residence. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(4), 558–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1772890.

McAuliffe, T., Thomas, Y., Vaz, S., Falkmer, T., & Cordier, R. (2019). The experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder: Managing family routines and mothers’ health and wellbeing. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(1), 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12524.