Abstract

While childhood bereavement is common, children’s bereavement needs are not well understood. It is recognized that children’s understandings of death fundamentally differ from those of adults, however, limited research has explored this from a child’s perspective. Insight about children’s understandings and needs can be drawn from the questions they ask about it. Bereaved children aged 5–12 years were invited to submit questions about death and grief during a camp for grieving children. Children’s questions (N = 213) from 10 camps were analyzed using conventional content analysis. Five themes were identified: Causes and Processes of Death; Human Intervention; Managing Grief; The Meaning of Life and Death; and After Death. Children’s questions revealed that they are curious about various biological, emotional, and existential experiences and concepts, demonstrating complex and multi-faceted considerations of death and its subsequent impact on their lives. Findings suggest that bereaved children may benefit from opportunities to freely discuss their thoughts about death, which may facilitate appropriate education and emotional support.

Highlights

-

Content analysis of 213 questions asked by bereaved children aged between 5 and 12 years resulted in five themes: Causes and Processes of Death, Human Intervention, Managing Grief, The Meaning of Life and Death, and After Death.

-

Bereaved children ask meaningful questions about death and grief and are curious about biological, emotional, and existential experiences and concepts.

-

Bereaved children may benefit from support that offers opportunities to ask questions alongside basic death and grief education, and strategies for emotion regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bereavement in childhood is common, with 5–7% of children in Western countries experiencing the death of a parent and/or sibling before age 18 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010; Burns et al., 2020; Parsons, 2011). When including the loss of other close family members and friends, over 50% of children have been bereaved (Harrison & Harrington, 2001; Paul & Vaswani, 2020). Of emerging concern is the effect of COVID-19, with an estimated 1.1 million children globally experiencing the death of a parent in the first 14 months of the pandemic (Hillis et al., 2021). The prevalence of childhood bereavement highlights the need for effective and appropriate support, particularly considering the potential for adverse outcomes following the loss of a close person. While grief reactions such as sadness are understandably common, childhood bereavement is associated with anxiety and depression, poor academic performance, suicidality, and the development of affective, psychotic, and substance use disorders (Burrell et al., 2018; Elsner et al., 2022; McKay et al., 2021; Simbi et al., 2020; Syer et al., 2021; Weinstock et al., 2021). Mitigating these impacts requires bereavement support for children that considers their unique understandings of death and experiences of grief.

Children’s understandings of death and dying are typically conceptualized within the biologically rooted death concepts of inevitability, universality, irreversibility, cessation, and causality (Hoffman & Strauss, 1985; Panagiotaki et al., 2018). Generally, children demonstrate formative understandings of death by age three, develop comprehension of some death concepts by age six, and reach a more complete understanding of death by age 10 (D’Antonio, 2011; Harris, 2018; Kentor & Kaplow, 2020; Panagiotaki et al., 2018). This evolving understanding is largely viewed as a function of cognitive and emotional development (McCoyd et al., 2021, p. 5); however, limited research explores death concepts from the child’s perspective (Ahmadi et al., 2019).

Insight about children’s understandings of death can be drawn from the questions they ask about it. The process of asking questions and receiving answers is key to making sense of death (Menendez et al., 2020). As reported by caregivers, children commonly ask, “Why do people die?”, “Will I die?”, and “Will you die?” demonstrating a developing understanding of the inevitability and universality of death (Gutiérrez et al., 2014; Renaud et al., 2015). Questions children ask about death may also offer insight into their bereavement needs. Martinčeková et al. (2020) asked adults who were bereaved as children to describe how they could have been better supported to cope with their loss. A key theme was the need for more information about death and grief, suggesting that children desire conversations about death and grief when they are bereaved. However, retrospective accounts of childhood bereavement are inevitably colored by adult cognitions and emotions, limiting the utility of these accounts to provide genuine insight into children’s bereavement needs.

Children largely rely on their caregivers to offer bereavement support and provide information about death (Menendez et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2019), and evidence suggests that children who receive this support and information cope better than those who are shielded from discussions about death and grief (Martinčeková et al., 2020). Yet adults are often reluctant to discuss death and dying with children (Fearnley, 2010; Hunter & Smith, 2008) and tend to underestimate children’s ability to comprehend death concepts (Gaab et al., 2013). By understanding the questions bereaved children have about death and grief, and centering their unique needs and experiences, caregivers may be better equipped to support bereaved children effectively and appropriately.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to better understand children’s bereavement needs by examining questions posed by bereaved children participating in a bereavement service. While previous research has investigated this retrospectively, few studies have sought to hear from bereaved children directly, meaning their needs may not be wholly understood or met. To address this gap, we invited bereaved children to ask questions about death and grief and used the resulting data to answer our research question: What do bereaved children want to know about death and dying?

Method

Lionheart Camp for Kids

Lionheart Camp for Kids (LCK) is a free day-camp that offers bereavement support to grieving children aged 5–17 years and their families (Griffiths et al., 2022). Based in Western Australia, LCK runs several times per year across two consecutive days where trained professionals and volunteers deliver grief psychoeducation to children and their caregivers through a series of developmentally appropriate activities. Caregivers can learn about the service through various avenues, including hospitals, schools, social media, and the LCK website (https://lionheartcampforkids.com.au/). As the service is designed to support grieving children and their families, only bereaved children are eligible to participate, however, there are no eligibility requirements related to grief symptoms. Children must be accompanied by their caregiver for the duration of the camp, and caregivers are expected to actively participate in camp activities.

On the first day of camp, facilitators normalize participants’ experiences by inviting them to share about their deceased family member before working through a series of structured activities (e.g., creating memory rocks) interspersed with breaks and free play. Children are also introduced to a centrally located question box on the first day and invited to anonymously submit questions about death and grief that are answered by a guest medical doctor the next day. Facilitators reassure the children that all questions are valid and will be answered. Children are encouraged to use the question box any time they have a question. If children have writing difficulty, facilitators write the child’s question verbatim, clarifying the meaning of a word only when necessary. On the second day, participants learn different coping strategies (e.g., grounding, breathing), caregivers are provided psychoeducation about child development and grief, and collaborative activities between children and adults are facilitated to encourage processing and meaning making.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by Curtin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HRE2020-0560). There was no formal assent process for children; however, families provided written informed consent to have any photos, videos, or activity data collected during the camp used for program promotion or evaluation research. Children’s questions from 10 camps run between July 2017 and April 2021 were collated and comprise the data for this study.

Participants

Participants were approximately 220 bereaved children who attended one of the 10 LCK camps included in the study. Children were aged between 5 and 12 years, with the mean age ranging from 7.4 years in 2017 to 8.7 years in 2021. There was an approximately even split of boys and girls. Most children were developmental typical, with several identified by their caregiver as having ADHD, Autism, or a sensory processing disorder. Most participants resided in Perth, Australia, with one camp for residents of Western Australia’s Southwest region. All children had experienced the death of a parent, sibling, or other family member (e.g., uncle, grandmother). Time since death ranged from four months to five years, with most losses occurring within the 12 months prior to attending the camp. Causes of death included cancer, road traffic crash, heart attack, suicide, workplace accident, substance use, and childhood illness. To maintain children’s anonymity, no demographic data were collected alongside the questions submitted by participants.

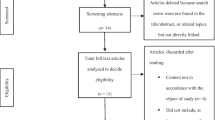

Data Analysis

Due to the limited literature available about children’s questions about death and grief, a conventional content analysis was used to analyze the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This approach is suitable for describing a phenomenon (i.e., children’s questions about death and grief) and allows data to be coded inductively, with categories formed from the data itself, rather than from predetermined coding structures or theories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The steps outlined by Hsieh and Shannon (2005) were followed. First, data were read for familiarity and immersion before being condensed into units of meaning. Codes were then iteratively derived by identifying words that captured discrete concepts. These codes were then sorted into categories. Relationships between categories were used to cluster codes into themes. See Table 1 for an example of the coding process.

Quality Criteria

The trustworthiness of the present study was supported through several quality criteria. First, the research was conducted by a multi-disciplinary team spanning psychology, social work, and medicine, with members bringing expertise in children’s development, parenting, grief and loss, and qualitative research. Second, dependability of the analysis and subsequent findings were supported through blind coding of all data by a second coder indicating satisfactory coding agreement, Cohen’s κ = 0.78 (Kyngäs et al., 2020). Reporting data quotes in their original state, including spelling and grammatical errors, supported confirmability, and credibility was supported through a detailed audit trail documenting analytic processes and decisions.

Findings

A total of 213 questions were submitted by children across the 10 camps. Twenty-three questions unrelated to the present study (e.g., questions about camp staff) were excluded. Five themes were determined from the remaining 190 questions: Causes and Processes of Death, Human Intervention, Managing Grief, The Meaning of Life and Death, and After Death (Table 2).

Causes and Processes of Death

Causes and Processes of Death was the most prominent category within the data and captured children’s curiosities and concerns regarding why and how people die. Children asked, “What tipe of sicknesses can pepol die from?” (Fig. 1) and “Have doctors found out how babys die?”, demonstrating a desire to understand what causes death. Regarding processes of death, children asked, “How does the body actually die?” and “Why do people die so fast?”. Children also asked about animal death, “How can animals die?”, suggesting children want to understand death processes in other living beings.

Children queried if certain conditions were contagious, “Is cancer contagious?” or hereditary, “If my dad died of cancer, does that mean I will die of that too?” and whether causes of death could come from animals, “Can humans get diseases from animals?”. These questions suggest children want to better understand various manners of death. Children also sought to understand the experience of death and dying, “How does it feel to die?” and “Does it hurt when you die?” Such questions demonstrate children’s consideration of how others might die. This was further exemplified in questions such as, “When will I die?”, and “How do I know when I’m dying?”, suggesting that children consider their own death and want to better understand how and when this might occur.

Children’s questions appeared to draw on their existing understandings and experiences. For example, one child asked, “Do people’s hearts shut down?”, reflecting some understanding of the heart’s function in keeping the body alive. Another child asked, “If someone is on life support and are all of their organs still working?”, which may reflect the child’s attempt to understand the death of someone they knew. Suicide and substance use were also referenced in some children’s questions, likely reflecting their loved one’s cause of death. Regarding suicide, children asked, “Why do people kill themselves?” and “What is depression? Why do people kill themselves because of it?”. In relation to substance use, questions asked were “Why do people get addiction? Why do they choose to do their addiction?”, “How do you get drunk?” and “Why would someone want to do drugs?”. Such questions demonstrate that children recognize and want to understand the factors that may contribute to suicide and substance use.

Human Intervention

Human Intervention captures questions related to preventing death and helping people who are dying. Children asked about specific technologies, such as pacemakers, “How does a paste maker work? Can a paste maker make a heart beet fast if it show down?” (Fig. 2) and treatments, “Is there a medicine that can stop cancer?”, “How can you cure heart cancer?” and, “If you have brain cancer, how many medicines will you have?”. A desire to understand contexts of death was also demonstrated, “Does everyone who goes to hospital die?”. Children’s questions suggest they want to know how death can be prevented or delayed.

Preventing future deaths was a concern for children who asked, “How can I protect my family from other people dying?” and “How can I cope without medication?”. These considerations may reflect children’s internalization of responsibility for their own and others’ death. Indeed, questions reflected children’s desire to help those who are dying, “Who can you we save people live or know to call 000 [the emergency number in Australia]?” and, “How to be a doctor or nurse?”. Children demonstrated varying levels of understanding of medical interventions, with some questions reflecting a desire to understand the purpose of such interventions, “Why do you help people when they’re dying?”, while others reflected concern with why help is not always offered, “Why don’t they always try to resuscitate people?”. Children wanted to better understand how people who are dying are medically supported, “How do doctors help?”, “Why do doctors give people tablets that can cause trouble?” and, “When people are close to dying, do they give them a needle/medicine?”. These questions suggest that knowledge of medical interventions is important to children’s understanding of death.

Managing Grief

Becoming Bereaved reflects children’s efforts to make sense of death and their subsequent social and emotional experiences. Questions such as “Why did he leve me?” (Fig. 3) and “Is it my fault?” suggest that children seek to understand death in relation to themselves and may perceive the death of a loved one as their responsibility. This was evidenced in one child’s question, “Did me having a cold when my dad had cancer and his immune system was low cause him to die?”. While this question suggests egocentric thinking (Hunter & Smith, 2008), it may also reflect a desire to understand death in a way that feels controllable. Similarly, another child asked, “People say it’s my fault dad killed himself, what do I do to make sure no one else kills themselves because of me?” Clearly, communication with children about death, and the reasons for it, is critical to avoid unnecessary pain caused by internalizing responsibility. Indeed, this was reflected in the questions, “I don’t think it’s fair people don’t tell kids the truth?” and “Why didn’t the doctors tell me dad was going to die?”

Children asked many questions about their experiences following bereavement, seeking to understand confusing emotional and physical responses. They sought to understand their emotions, with questions such as, “Why do I feel sometimes happy and sad at the same time?” and “Why am I more sad than my brother? Did he love mum less than me?”. Children also sought to understand physical responses such as changes to their sleep, “Why do I sleep all the time?” and “Why can’t I sleep at night?”, and physical sensations, “Body feels constant pains. Chest pains etc. What is this?” and “Why do people cry?”. These questions may reflect children’s limited understanding of how emotions manifest physically. Children’s questions also reflected a desire to understand the purpose of their emotions, “Why do we have to deal with grief?”, and how to manage them, “How can I deal with someone dying?”, “How do you not miss them?”, and “How can you handle your big feelings”. Children’s difficulty coping with grief was evidenced in questions such as, “How do I hurt myself without people knowing instead of overheating and burning myself?”. Emotion regulation skills are evidently an important aspect of bereavement support for children.

Questions relating to children’s social world were evident. Some children reflected concerns about their security, “What will happen to me if my mum dies too?”, and others sought assistance with gaining support, “Can someone help my teacher, she doesn’t understand?”. These questions demonstrate children’s future-oriented thinking and considerations of how their life has and may be impacted by bereavement. Social comparisons also appeared relevant to children’s understanding of their own grief as they sought to understand changes in their social world, “Why do kids bully me at school now?”, and how they relate to others, “Why do you sometimes feel jealous of other people who have not had other people in their family die?” and “How do I come across normal to other people?”. Children are evidently alert to how they are perceived, which may represent an additional source of stress accompanying the existing pain of loss.

The Meaning of Death

The meaning of death captures children’s questions about life’s purpose and why people die. Questions such as, “What is the meaning of life?” (Fig. 4) and “What is the point of living if you just have to die?” demonstrate children’s existential considerations.

Such considerations were further evidenced in complex questions such as, “If kids don’t have a dad, why would god let their mum die?”, “Why do people have to die at 50 and under?” and, “How did my nana and granddad live for that much years? But mum died young?”. These questions reflect pre-existing understandings of life and death that have been called into question as a result of bereavement.

A desire to understand who dies and who lives was apparent in questions such as, “Why do some sick people get better and some don’t?” and “Why do doctors make some people better but not others?”, as was a desire to understand the meaning of death, “Why do people diy?”, “Why do baby’s die?” and, “Why do people have disseses?”. Children’s questions reflect complex thoughts that suggest their understandings of death and dying are multi-faceted and potentially philosophical.

After Death

The final category, After Death, comprises questions relating to what happens to a person once they have died. Many questions related to continued existence after death, with questions related to how an individual who has died continues to live, “What do you do when you die?”, “Where do we go when we die?”, “Can you see people when you’re dead?” and, “Will my uncle see my pet dog in the afterlife?” Heaven featured prominently as an after-death destination, with children asking, “What is heaven?”, “Is heaven real?”, “Do you go to heaven after you die?”, “Can you still love people from heaven?”, and “What does it feel like to be in heaven?” (Fig. 5). This likely reflects a dominant cultural narrative surrounding death.

Children also asked about reincarnation, “Will my uncle be born again as a human or as an animal?”, and future interactions with the person who died, “If daddy comes back…” and “Can I still talk to my important person?”. Such questions demonstrate children’s developmental inability to understand the permanency of death and reflect a desire to maintain contact and connection with their lost loved one.

Discussion

The present research sought to understand what bereaved children want to know about death and grief. Using conventional content analysis, questions about death and grief were collated and analyzed, offering insight into bereaved children’s thoughts and feelings. Questions revealed that children are curious about various biological, emotional, and existential experiences and concepts, demonstrating complex and multi-faceted considerations of their loved one’s death and its subsequent impact on their lives.

Broadly, children’s questions appeared to serve a confirmatory function, with their questions relating to death concepts known to be developing in childhood, such as universality, irreversibility, and inevitability (Hunter & Smith, 2008). Such questions suggest that children actively construct their understanding of death through learning processes proposed by Piaget and Vygotsky. Children’s questions are attempts at discovery; the death of their loved one causes disequilibrium in their mental model, and they seek to correct this through discovery of new information (Piaget, 1954, pp. 350–379). Further, children rely on others (in this case a doctor) to provide the answers, thereby developing their mental model in a social context (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 24). Children’s questions are formed based on existing knowledge, but they seek to explain inconsistencies or newly discovered gaps as a result of bereavement by posing questions to others in their social world.

Children’s questions demonstrated varying degrees of understanding and knowledge, likely reflecting differences in age-based cognition. This supports age-based approaches to bereavement supports, though individual differences should be considered. While we are not able to account for the role of age in children’s questions due to the anonymous nature of our data collection, the questions children ask about death reflect knowledge within their zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 84). Regardless of age, individuals work through three stages when learning: (1) what cannot be understood or achieved, even with guidance, (2) what can be understood or achieved with guidance (the zone of proximal development), and (3) what can be understood and achieved independently. This model underpins scaffolding, an approach to education recognizing that individuals require a lot of guidance and support when they are first learning a skill/concept, which is tapered as the individual progresses to mastery. Therefore, the answers given to children’s questions about death and grief must be within their scope of understanding, which is informed not just by their biological age, but also their life experiences. A child who has previously been exposed to death is likely to have different questions than a child who is experiencing their first exposure to death, even if they are of the same biological age. Likewise, a child who has not been bereaved is likely to ask different questions compared to a child who has been bereaved. Therefore, children’s questions are informed by their experience and reflect their zone of proximal development, informing the question recipient of what may or may not be within the child’s scope of understanding.

A preponderance of questions related to biological concepts, with a focus on the causes, processes, and states of death and dying. This is consistent with the literature demonstrating that children’s understandings and conceptualizations of death are largely biological (Harris, 2018; Vázquez-Sánchez et al., 2019; Yang & Park, 2017) and supports the recommendation for death education to be integrated into formal curricula across all education levels (McAfee et al., 2022). Children are likely to benefit from death education that incorporates comprehensive information about the causes and processes of death and dying, with increasingly complex death concepts introduced as their education progresses (McAfee et al., 2022).

Children’s questions demonstrated their need to make sense of death. For some children, this learning was grounded in egocentric thinking, as seen in questions like, “Why did he leve me?” and “Is it my fault?”. Perceptions of personal responsibility are common among grieving children (Kentor & Kaplow, 2020) and this finding reflects the importance of discussing death with children. While egocentric thinking tends to dissipate with age, there is potential for such thinking to lead to thoughts of abandonment or responsibility, which can perpetuate distress and foment guilt (Cohen et al., 1977; Raveis et al., 1999). Dispelling such thoughts is important; however, children are aware of adults’ tendency to censor death-related information (Paul, 2019) and may be reluctant to ask questions as a result. Due to the anonymous nature of the data collected in the present study, children may have asked questions otherwise kept hidden. Therefore, these findings provide support for open discussions with bereaved children about death.

Metaphysical conceptualizations of death, such as those involving considerations of the afterlife, were common in children’s questions, as they sought to make sense of what happens after someone dies. Consistent with other research (Vázquez-Sánchez et al., 2019), heaven was a frequent afterlife concept. This likely reflects dominant Western cultural narratives present in Australia, whereby heaven is often referred to in discussions with children about death (Arruda-Colli et al., 2017; Renaud et al., 2015). While we did not record participants’ religious affiliation, Australian Census data shows Christianity to be the most endorsed religion (52.1% of respondents in 2016 and 43.9% of respondents in 2021; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022). As such, this offers a potential explanation for the commonality of Christian death concepts such as heaven. Cultural and religious differences among children in the present sample could not be accounted for but are important avenues for further inquiry. Culture and religion have important implications for how adults understand and experience bereavement (e.g., Rosenblatt, 2008, pp. 207–222), which could be the case for children, too.

Consistent with the literature (see Dalton et al., 2019 for a review), children’s questions demonstrated a desire to be told their loved one was dying. Children wish to be informed of their loved one’s possible/inevitable death and shielding children from such knowledge may be detrimental, leading to tension, distress, and anxiety (Dalton et al., 2019). It is likely that children would benefit from discussions about a loved one’s inevitable death, allowing for psychological preparation; however, children are aware of adults’ reluctance to discuss death with them, and this serves as a barrier to such discussions (Paul, 2019). Equipping caregivers with tools and strategies to effectively engage in discussions about death with their children is key to preparing children for the death of a loved one and supporting them after bereavement. Research with adults caring for a close person near death shows that many are not prepared (Breen et al., 2018). Thus, preparing children for bereavement likely means preparing the adults around them, too.

Children’s needs after bereavement were evident in the questions they asked about how to cope with and manage difficult emotional experiences, demonstrating their need for emotional support, including co-regulation, validation, and reassurance. Emotion regulation skills are an established need for grieving children (Ahmadi et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2019; Youngblut & Brooten, 2021) but caregivers often struggle to find the best approach. Given the importance of the caregiving environment to children’s processing of grief (Alvis et al., 2022), it is critical that caregivers are offered ample support and knowledge to effectively provide safe and supportive environments. Interventions such as Lionheart Camp for Kids (Griffiths et al., 2022) offer a structured and active environment to offer children and their caregivers such supports. Children tend to be exposed to death through media (e.g., books, television, films) or non-human loss (e.g., death of an insect) prior to losing a close person (Renaud et al., 2015; Zedníková & Pechová, 2015), there is opportunity for caregivers to capitalize on the early questions children ask to provide them with a comprehensive understanding and set of coping skills.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the present study offers important insights into the types of questions bereaved children ask about death and grief, there are several factors that we could not account for. Due to the anonymous nature of the data collection, we were unable to compare questions based on demographic details such as age, sex, race, religion, or culture, which are likely crucial to our understanding of what bereaved children need. Likewise, we were unable to compare questions based on children’s relationship with the deceased (e.g., parent compared to sibling), the manner of death (e.g., terminal illness compared to suicide), and time since loss (e.g., one month compared to one year ago). Such information could offer insight into children’s needs at varying stages of their bereavement experience and depending on who died and how. Future research on bereaved children’s questions should account for these details to strengthen our understanding of what children want to know about death and grief, and improve the bereavement supports designed for them.

The data collection method allowed for children to ask questions anonymously in their own time, a naturalistic approach that may have captured questions from children that could be missed in time-bound and identifiable settings such as an interview or focus group. Despite the potential benefits of this approach, there are several drawbacks to note. First, children with limited writing abilities or verbal expression may not be well-represented in our data. While children who had difficulty writing were assisted by a camp facilitator, this process may have impeded the methodological benefit of anonymity. Second, handwritten notes were decontextualized, meaning ambiguity could not be resolved. Lastly, all notes were interpreted through an adult lens. Children’s meanings may be interpreted inaccurately or incompletely due to cognitive and experiential differences.

The lack of identifying information also meant we could not determine with certainty how many questions each child asked. It is possible a small subgroup of children asked lots of questions, rather than the questions representing the broader sample of children. Similarly, while the age range of camp participants was 5–12 years, we cannot know whether the full age range was captured in our data set, which limits the conclusions we can draw about the relevance of the questions to any given age. In future research, data collection could be adapted to include a space for children to record their age alongside their question. This would retain anonymity while giving additional detail to contextualize questions. Generalizability is further limited by the sample. Participants comprised children participating in a single bereavement program located in Western Australia; a more complete understanding of the questions children have about death and grief necessitates multiple-site recruitment and data collection from diverse samples of children.

While the aim of this study was to categorize the questions bereaved children ask about death and grief, the nature of the data means that only a conceptual understanding of children’s questions can be gained. In absence of data related to children’s lived experiences and the context of their questions, the present research cannot offer a nuanced picture of what children want to know about death and grief. For example, we are unable to determine whether children only asked questions related to the death of their own loved one, or if their questions advanced beyond their direct experience and reflected things they had been exposed to at camp. Given that children hear about each other’s bereavement experiences during the camp, their questions may capture not just their own experiences but those of other children as well. Future research might catalog children’s questions over time to examine temporal changes in their questions.

Finally, while children’s questions reflected current understanding of children’s death concepts, it is possible that the focus on medical and biological aspects emerged because children knew their questions would be answered by a medical doctor. If questions were answered by a different expert (e.g., psychologist, teacher, individual with lived experience), different questions may have been posed. Future research might investigate the effect of different types of experts on children’s questions, which may be useful for directing more specific preparation to those involved in the care of bereaved children.

Practical Implications

The questions bereaved children ask about death and grief can be seen as windows into their cognitive-emotional processing. As such, they may serve as indications of a child’s current understandings and be used to direct appropriate and suitable bereavement supports. For example, questions such as “How can I protect my family and other people from dying?” and “Is it my fault?” indicate a child may be internalizing responsibility for the death of their loved one. This type of question requires a response that reassures the child they are not to blame for the death and that they cannot prevent the death of others, without causing undue fear of death. The information provided to children about death and grief should consider not just what is deemed age-appropriate, but also what is relevant for a child’s own level of understanding.

In the present study, children’s questions indicated an overarching need for pre-emptive psychosocial education. With many questions related to making sense of physiological, emotional, and social experiences, bereaved children may benefit from explanations of what to expect. For example, children asked about body pains and sleep difficulties, suggesting they need to be taught how grief (and other emotions) can manifest in the body and ways to manage these physiological experiences. Likewise, questions like “How do you not miss them?” and “Why am I more sad than my brother?” suggests a need for education about emotions, including their purpose and how to cope with them. This kind of education could serve to normalize grief experiences and prepare children for emotions they may otherwise find confusing and distressing.

Additionally, helping children navigate social relationships and school contexts after bereavement may assist with questions such as, “Why do kids bully me at school now?” and “Can someone help my teacher, she doesn’t understand?”. Children may not expect to be treated differently following bereavement; education about how others may act could be beneficial by preparing them for difficult interactions and equipping them with ways to manage such experiences. Being able to answer children’s questions requires adults understanding that avoiding the topics of death and grief is not helpful when children are naturally curious. Adults involved in the care of children need appropriate death literacy (Noonan et al., 2016) and grief literacy (Breen et al., 2022) to feel more comfortable taking about these issues with children.

Integrating death education into school curricula can be an effective approach to pre-emptively supporting children to cope with bereavement. Doing so provides preparatory guidance, which equips children with knowledge, language, and coping strategies that can be drawn upon when a child faces loss (McGuire et al., 2013). Although not currently standard practice in Australian schools (Kennedy et al., 2017), international death education curricula typically incorporate information that facilitates recognition and understanding of grief, language to identify and explain grief, and strategies to cope with grief and related experiences (Dawson et al., 2023; Friesen et al., 2020). In combination with professional development for educators, death education can prepare children and adults to better manage bereavement. For example, when asked, “Why am I more sad than my brother?”, an educator can explain that everyone’s experiences of grief are different, with reference to concepts discussed during death education lessons. With widespread integration of death education, social issues may also be addressed, reducing the likelihood of bullying and isolation (Stylianou & Zembylas, 2018).

Conclusion

This study contributes to a growing body of literature focusing on the experiences and perspectives of bereaved children. Through an anonymous method of data collection, we were able to collate and analyze children’s questions about death and grief, finding that children are curious about practical, social/relational, and emotional/experiential aspects of death and grief. While children’s questions were grouped into five themes, these were underpinned by two core findings. First, children’s understanding of death begins with biology, which provides an anchor point from which other death and grief concepts can be built. Second, children require psychosocial education to prepare them for bereavement and equip them with tools and knowledge to understand and manage physiological, emotional, and social bereavement experiences. These findings provide valuable insight into bereaved children’s thoughts and curiosities about death and grief and illustrate the importance of adults around them being sufficiently equipped to elicit and answer such questions. Children’s bereavement supports may benefit from considering not just what children need to know, but also what children want to know about death and grief.

Change history

07 December 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02724-8

References

Ahmadi, F., Ristiniemi, J., Linblad, I., & Schiller, L. (2019). Perceptions of death among children in Sweden. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 24, 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364436X.2019.1672627.

Alvis, L., Zhang, N., Sandler, I. N., & Kaplow, J. B. (2022). Developmental manifestations of grief in children and adolescents: Caregivers as key grief facilitators. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 16(2), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00435-0.

Arruda-Colli, M. N. F., Weaver, M. S., & Wiener, L. (2017). Communication about dying, death, and bereavement: a systematic review of children’s literature. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20, 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0494.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Australian social trends September 2010: parental divorce or death during childhood (catalogue no. 4102.0). https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/LookupAttach/4102.0Publication29.09.105/$File/41020_DeathDivorce.pdf.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Religious affiliation in Australia: exploration of the changes in reported religion in the 2021 Census. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/religious-affiliation-australia#change-in-religious-affiliation-over-time.

Breen, L. J., Aoun, S. M., O’Connor, M., Howting, D., & Halkett, G. K. B. (2018). Family caregivers’ preparations for death: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55, 1473–1479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.018.

Breen, L. J., Kawashima, D., Joy, K., Cadell, S., Roth, D., Chow, A., & Macdonald, M. E. (2022). Grief literacy: a call to action for compassionate communities. Death Studies, 46, 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1739780.

Burns, M., Griese, B., King, S., & Talmi, A. (2020). Childhood bereavement: understanding prevalence and related adversity in the United States. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90, 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000442.

Burrell, L. V., Mehlum, L., & Qin, P. (2018). Sudden parental death from external causes and risk of suicide in the bereaved offspring: a national study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.023.

Cohen, P., Dizenhuz, I. M., & Winget, C. (1977). Family adaptation to terminal illness and death of a parent. Social Caeswork, 58(4), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/104438947705800404.

Dalton, L., Rapa, E., Ziebland, S., Rochat, T., Kelly, B., Hanington, L., Bland, R., Yousafzai, A., & Stein, A. (2019). Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition in their parent. Lancet, 393(10176), 164–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33202-1.

Dawson, L., Hare, R., Selman, L. E., Boseley, T., & Penny, A. (2023). The one thing guaranteed in life and yet they won’t teach you about it’: the case for mandatory grief education in UK schools. Bereavement, 2. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.54210/bj.2023.1082.

D’Antonio, J. (2011). Grief and loss of a caregiver in children: a developmental perspective. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 49, 17–20. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20110802-03.

Elsner, T. L., Krysinska, K., & Andriessen, K. (2022). Bereavement and educational outcomes in children and young people: a systematic review. School Psychology International, 43, 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343211057228.

Fearnley, R. (2010). Death of a parent and the children’s experience: don’t ignore the elephant in the room. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24, 450–459. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903274871.

Friesen, H., Harrison, J., Peters, M., Epp, D., & McPherson, N. (2020). Death education for children and young people in public schools. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 26(7). https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2020.26.7.332.

Gaab, E. M., Owens, G. R., & MacLeod, R. D. (2013). Caregivers’ estimations of their children’s perceptions of death as a biological concept. Death Studies, 37, 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2012.692454.

Griffiths, N., Mazzucchelli, T. G., Skinner, S., Kane, R. T., & Breen, L. J. (2022). A pilot study of a new bereavement program for children: Lionheart Camp for Kids. Death Studies, 46, 780–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1702121.

Gutiérrez, I. T., Miller, P. J., Rosengren, K. S., & Schein, S. S. (2014). Affective dimensions of death: children’s books, questions, and understandings. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 79, 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12078.

Harrison, L., & Harrington, R. (2001). Adolescents’ bereavement experiences: prevalence, association with depressive symptoms, and use of services. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0379.

Harris, P. L. (2018). Children’s understanding of death: from biology to religion. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170266. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0266.

Hillis, S. D., Unwin, H. J., Chen, Y., Cluver, L., Sherr, L., Goldman, P. S., Ratmann, O., Donnelly, C. A., Bhatt, S., Villaveces, A., Butchart, A., Bachman, G., Rawlings, L., Green, P., Newson, C. A., & Flaxman, S. (2021). Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: a modelling study. The Lancet, 398, 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01253-8.

Hoffman, S. I., & Strauss, S. (1985). The development of children’s concepts of death. Death Studies, 9, 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481188508252538.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Hunter, S. B., & Smith, D. E. (2008). Predictors of children’s understandings of death: age, cognitive ability, death experiences and maternal communicative competence. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 57(2), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.57.2.b.

Kennedy, C. J., Keefe, M., Gardner, F., & Farrelly, C. (2017). Making death, compassion and partnership ‘part of life’ in school communities. Pastoral Care in Education, 35(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2017.1306873.

Kentor, R. A., & Kaplow, J. (2020). Supporting children and adolescents following parental bereavement: guidance for health-care professionals. Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 4, 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30184-X.

Kyngäs, H., Kääriäinen, M., Elo, S. (2020). The trustworthiness of content analysis. In H. Kyngäs, K. Mikkonen, & M. Kääriäinen (Eds.), The application of content analysis in nursing science research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6_5.

McCoyd, J.L., Koller, J., & Walter, C.A. (2021). Grief and loss: theories and context. In Grief and loss across the lifespan: A biopsychosocial perspective (pp. 29–58). Springer Publishing Company. https://portal.igpublish.com/iglibrary/search/SPCB0002265.html.

Martinčeková, L., Jiang, M. J., Adams, J. D., Menendez, D., Hernandez, I. G., Barber, G., & Rosengren, K. S. (2020). Do you remember being told what happened to grandma? The role of early socialization on later coping with death. Death Studies, 44, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1522386.

McAfee, C. A., Jordan, T. R., Cegelka, D., Polavarapu, M., Wotring, A., Wagner-Greene, V. R., & Hamdan, Z. (2022). COVID-19 brings a new urgency for advance care planning: implications of death education. Death Studies, 46, 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1821262.

McGuire, S. L., McCarthy, L. S., & Modrcin, M. A. (2013). An ongoing concern: helping children comprehend death. Open Journal of Nursing, 3, 307–313. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2013.33042.

McKay, M., Cannon, M., Healy, C., Syer, S., O’Donnell, L., & Clarke, M. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relationship between parental death in childhood and subsequent psychiatric disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143, 472–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13289.

Menendez, D., Hernandez, I. G., & Rosengren, K. S. (2020). Children’s emerging understanding of death. Child Development Perspectives, 14, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12357.

Noonan, K., Horsfall, D., Leonard, R., & Rosenberg, J. (2016). Developing death literacy. Progress in Palliative Care, 24, 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699260.2015.1103498.

Panagiotaki, G., Hopkins, M., Nobes, G., Ward, E., & Griffiths, D. (2018). Children’s and adults’ understanding of death: cognitive, parental, and experiential influences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.014.

Parsons, S. (2011). Long-term impact of childhood bereavement. Preliminary analysis of the 1970 British Cohort Study. Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre. https://www.basw.co.uk/system/files/resources/basw_31420-6_0.pdf

Paul, S. (2019). Is death taboo for children? Developing death ambivalence as a theoretical framework to understand children’s relationship with death, dying and bereavement. Children & Society, 33, 556–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12352.

Paul, S., & Vaswani, N. (2020). The prevalence of childhood bereavement in Scotland and its relationship with disadvantage: the significance of a public health approach to death, dying and bereavement. Palliative Care and Social Practice, 14, 263235242097504. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632352420975043.

Piaget, J. (1954). The elaboration of the universe. In The construction of reality in the child (pp. 350–379). Routledge.

Raveis, V. H., Siegel, K., & Karus, D. (1999). Children’s psychological distress following the death of a parent. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021697230387.

Renaud, S.-J., Engarhos, P., Schleifer, M., & Talwar, V. (2015). Children’s earliest experiences with death: Circumstances, conversations, explanations, and parental satisfaction. Infant and Child Development, 24, 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1889.

Rosenblatt, P.C. (2008). Grief across cultures: a review and research agenda. In M.S. Stroebe, R.O. Hansson, H. Schut, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (pp. 207–222). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14498-010.

Simbi, C. M. C., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Z. (2020). Early parental loss in childhood and depression in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-controlled studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.087.

Scott, R., Wallace, R., Audsley, A., & Chary, S. (2019). Young people and their understanding of loss and bereavement. Bereavement Care, 38, 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682621.2019.1588560.

Stylianou, P., & Zembylas, M. (2018). Dealing with the concepts of “grief” and “grieving” in the classroom: children’s perceptions, emotions, and behavior. OMEGA, 77(3), 240–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815626717.

Syer, S., Clarke, M., Healy, C., O’Donnell, L., Cole, J., Cannon, M., & McKay, M. (2021). The association between familial death in childhood or adolescence and subsequent substance use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 120, 106936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106936.

Vázquez-Sánchez, M. J., Fernández-Alcántara, M., García-Caro, M. P., Cabañero-Martínez, M. J., Martí-García, C., & Montoya-Juárez, R. (2019). The concept of death in children aged from 9 to 11 years: evidence through inductive and deductive analysis of drawings. Death Studies, 43, 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1480545.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Weinstock, L., Dunda, D., Harrington, H., & Nelson, H. (2021). It’s complicated: adolescent grief in the time of Covid-19. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 638940. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638940.

Yang, S., & Park, S. (2017). A sociocultural approach to children’s perceptions of death and loss. OMEGA, 76, 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817693138.

Youngblut, J. M., & Brooten, D. (2021). What children wished they had/had not done and their coping in the first thirteen months after their sibling’s neonatal/pediatric intensive care unit/emergency department death. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 24, 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0538.

Zedníková, K., & Pechov, O. (2015). Communication about death in the family. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 6(2), 253–259. https://doi.org/10.15452/CEJNM.2015.06.0012.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Lionheart Camp for Kids had no role in the design of the study or in the analysis and interpretation of data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joy, C., Staniland, L., Mazzucchelli, T.G. et al. What Bereaved Children Want to Know About Death and Grief. J Child Fam Stud 33, 327–337 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02694-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02694-x