Abstract

Using a vignette approach, two studies examined the impact of three factors on judgments of parental competence: target parents’ sexual orientation, gender, and parenting behavior. According to the aversive prejudice framework, people should express their subtle prejudice against lesbian and gay parents when the latter show detrimental parenting behavior––that is, when devaluation is easy to rationalize. Samples of 170 and 290 German heterosexual participants each were presented with a parent-child conflict situation. In Study 1, the child threw a public tantrum during a restaurant visit; in Study 2, the children wanted to play outside instead of doing their homework. Irrespective of target gender, lesbian and gay parents were judged as equally or even somewhat more competent than heterosexual parents. In both studies, parents who responded in an authoritative way received the most positive evaluation of parental competence, whereas parents who responded in an authoritarian way received the most negative evaluation. In neither study, however, there was a significant interaction between parents’ sexual orientation and parenting behavior. That is, contrary to hypothesis, lesbian and gay parents did not receive more negative evaluation than heterosexual parents when responding in a comparatively negative, authoritarian or permissive way. Such interaction could also not be found when additionally considering participants’ levels of homonegativity or social desirability. The discussion centers on the increasing acceptance of same-sex parenthood as well as the high appreciation of authoritative parenting in contemporary Germany.

Highlights

-

How do parents’ sexual orientation, gender, and parenting style influence judgments of parental competence?

-

Study participants did not express overt or subtle prejudice against lesbian or gay parents.

-

Irrespective of sexual orientation or gender, authoritative parents were judged most positively.

-

Permissive parents ranked middle, authoritarian parents were judged most negatively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In Western societies, the acceptance of homosexuality has greatly increased during the last decades (Adamczyk & Liao, 2019; Gerhards, 2010; Smith et al., 2014). This change is intricately interwoven with the amelioration of the legal situation of lesbian and gay (LG) people that has taken place in many countries (Abou-Chadi & Finnigan, 2019; Aksoy et al., 2018; Flores & Barclay, 2016). In Germany, where the present study was conducted, homosexuality was not formally decriminalized until 1994, when the West and East German legal codes had to be aligned due to the reunification process. The most important milestones toward equal rights for LG people were the legalization of same-sex partnerships in 2001 and, 16 years later, the “marriage for all” act. Only the latter included full adoption rights for LG couples. Nevertheless, LG parenthood remains an issue of debate, at least among political and religious conservatives, as population-based surveys show (Decker & Brähler, 2020; Dotti Sani & Quaranta, 2020; Takács et al., 2016). Opponents often claim that LG people are unfit for parenthood and that children growing up in rainbow families develop worse (e.g., due to lacking role models or more peer discrimination; Clarke, 2001; Kleinert et al., 2015; Pratesi, 2012). A wealth of research shows, however, that LG parents are fully capable of providing stable and warm family environments, and that they raise as healthy and happy children as their heterosexual counterparts (Farr et al., 2019; Fedewa et al., 2015; Patterson, 2016). The present research aims to provide deeper insight into the social judgment of LG parenthood. Specifically, we investigate whether the attribution of parental competence depends on the interplay between target parents’ sexual orientation, gender, and parenting style.

Over the last years, numerous social psychological studies have been conducted on the judgment of LG parenthood. Many of them, as the present one, used a vignette approach. Study participants are presented with a couple who want to become parents (Camilleri & Ryan, 2006; Crawford & Solliday, 1996; Gato & Fontaine, 2013, 2016a, 2016b, 2017; Kranz, 2020, 2022; McCutcheon & Morrison, 2015; Rye & Meaney, 2010; Sohr-Preston et al., 2017; Steffens et al., 2015; Webb et al., 2020) or with parents who are challenged by their child’s behavior (Baiocco et al., 2013; Carnaghi et al., 2018; Di Battista et al., 2021; Kranz, 2022; Massey, 2008; Massey et al., 2013; McLeod et al. 1999; Morse et al. 2007; O’Flynn & White 2020; Štrbić et al. 2019; Tušl et al. 2020). In these vignettes, everything is kept constant, except for the sexual orientation of the (future) parents (and, possibly, further factors of interest). After reading the vignette, participants are asked to rate the vignette target’s parental competence (or other child- or family-related variables). As hypothesized based on persisting anti-LG prejudice, most studies found that LG targets were judged more negatively than their heterosexual counterparts; a considerable number of studies, however, did not find the expected LG target disadvantage (Camilleri & Ryan, 2006; Di Battista et al., 2021; Kranz, 2020, 2022; Massey, 2008; McCutcheon & Morrison, 2015; Štrbić et al., 2019; Tušl et al., 2020).

We will now take a closer look at some vignette studies that are of specific relevance to the present research. In Study 1, we applied a vignette that had been introduced by Massey (2008). The author presented an almost exclusively heterosexual US sample with a restaurant situation in which the parents had to deal with their child’s public tantrum. Target parents had an LG or heterosexual orientation, the latter with either the mother or the father intervening in the child’s behavior. Contrary to Massey’s first hypothesis, gay fathers’ parental competence was rated most positively and heterosexual parents’ competence most negatively, especially when the mother was the active parent. Massey’s second hypothesis referred to the differentiation between traditional and modern homonegativity1, adopted from racism research (McConahay, 1986). Traditional homonegativity refers to the judgment of same-sex orientation as unnatural, pathologic, immoral, or sinful, whereas modern homonegativity is indicated by the view that anti-LG discrimination is no longer a problem in modern society (Massey, 2009), insinuating that LG people want to make exaggerated demands and take unjustified advantages when pretending ongoing discrimination against them (see also Morrison & Morrison, 2002). As expected, Massey found that both traditional and modern homonegativity contributed to predict the attribution of (low) parental competence to LG parents. That is, neither form of homonegativity was redundant.

One factor that might explain inconsistent findings on the (non-) prejudicial perception of LG parenthood is aversive prejudice. The differentiation between blatant and aversive prejudice also traces back to racism research (for an overview, see Dovidio et al., 2017). Given the growing pressures toward egalitarianism in Western societies, it is suggested that blatant prejudice would threaten people’s tolerant self-view and/or evoke negative social responses. Therefore, discrimination today mainly occurs in situations when one can justify a negative response toward a member of a prejudiced group on the basis of some factor other than the prejudice itself. Dovidio and Gaertner’s (2000) vignette study illustrates very well how aversive prejudice works. Participants were White students from the US, recruited independently in 1989 and 1999. They were provided with the credentials of either a Black or a White applicant for a specific campus position. When the credentials clearly qualified or disqualified the candidate, the Black applicant was as likely to be recommended as the White one. When the candidate’s qualification was ambiguous, however, participants recommended the White applicant significantly more often than the Black one––with exactly the same credentials. This pattern was stable across time, whereas blatant expressions of prejudice, as measured with a traditional racism scale, declined over the 10-year period.

Of course, Dovidio et al.’s (2017) aversive prejudice framework is not restricted to racism research but can be applied to any prejudiced group including sexual minorities (see, e.g., Hoffarth & Hodson, 2014; Moreno & Bodenhausen, 2001). Using again the restaurant vignette, Massey et al. (2013) applied the aversive prejudice framework to the social judgment of LG parenthood. In addition to target parents’ sexual orientation, the authors varied parents’ response to the child’s tantrum: it was either positive or negative (or, in Baumrind’s, 1966, terminology, authoritative versus authoritarian; we will come back to this). A small but significant three-way interaction between target parents’ sexual orientation, parenting behavior, and participants’ level of modern homonegativity emerged. The means were in the expected direction. Only in the negative parenting condition, participants scoring above the mean of the modern homonegativity scale rated LG parents as less competent than heterosexual parents. A-posteriori testing of this interaction, however, failed to reach statistical significance. From a methodological perspective, Massey et al.’s analysis is concerned with two major issues: the mean-dichotomization of the homonegativity scale (loss of measurement reliability and statistical power; MacCallum et al., 2002) and testing the three-way interaction without including the two-way interaction into the analysis of variance (violation of the hierarchical principle of the general linear model; Rosnow & Rosenthal 1989).

Recently, two European studies replicated Massey et al.’s (2013) study (or, more precisely, its experimental part). Štrbić et al. (2019) conducted their study in the Croatian context, using a heterosexual student sample. Target parents’ sexual orientation had no significant impact on participants’ evaluation of parental competence, neither as a main effect nor in interaction with parenting behavior and/or parents’ gender. The same pattern emerged in the Czech context, where Tušl et al. (2020) also used a predominantly heterosexual student sample. Taken together, both studies contradicted the blatant as well as aversive prejudice hypothesis stating cross-situational versus situation-specific devaluation of LG parenthood. Unfortunately, neither study considered participants’ levels of traditional versus modern homonegativity.

The present research also replicates, but also extends Massey et al.’s (2013) study in Germany. To the best of our knowledge, so far, three vignette studies examined the social judgment of LG parenthood in the German context. Using a predominantly heterosexual sample, Steffens et al. (2015) found that target gender, age, and socioeconomic status explained as much, or even more, variance in the attribution of adoption suitability to adoption seeking couples than target sexual orientation. Participants attributed more adoption suitability to female, younger, and socioeconomically advantaged adoption applicants. Gay, but not lesbian, couples were perceived as somewhat less suitable for adoption than heterosexual couples, but this effect was comparably small. Using an exclusively heterosexual sample, Kranz (2022) found that LG adoption-seeking couples as well as LG parent couples were perceived as equally competent in parenting as their heterosexual counterparts, irrespective of whether the latter were (future) adoptive or biological parents. In another study, Kranz (2020) found that target gender role (in terms of the “big two,” feminine communion and masculine agency; Bakan, 1966), but not target sexual orientation or gender, explained variance in the attribution of parental competence and adoption suitability. Irrespective of whether adoption-seeking couples were LG or heterosexual, or of whether they were female or male, communion-oriented targets were perceived as more competent in parenting and, correspondingly, more suitable for adoption, than agency-oriented targets.

Apparently, there is no clear evidence for general LG parenthood disadvantage in the German context either. Therefore, we continue to examine whether such disadvantage only occurs in negative situations, as predicted by the aversive prejudice framework (Dovidio et al., 2017). Specifically, we refer to Baumrind’s (1966) typology of three parenting styles: authoritarian, permissive, and authoritative. Two core dimensions, demandingness and responsiveness, are suggested to underlay the three parenting styles. Demandingness refers to the degree to which the parent places rules for their child and directs the child to follow these rules. Responsiveness refers to the degree to which the parent responds to the child’s needs in a sensitive and supportive way. Authoritarian parenting is characterized by high demandingness and low responsiveness, whereas permissive parenting is characterized by low demandingness and high responsiveness. High levels of demandingness as well as responsiveness characterize authoritative parenting. There is clear evidence that authoritative parenting is most conducive to children’s welfare. It is associated with children’s mental health as well as cognitive and social development (for meta-analyses, see Pinquart, 2016, 2017a, 2017b), and there is more cross-cultural similarity than difference regarding the benevolent role of authoritative parenting (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Authoritarian and permissive parenting are comparatively detrimental, as they each lack one of the two positive parenting factors (demandingness or responsiveness, respectively).

Aims and Hypotheses

Using a vignette methodology and based on the idea of subtle homonegativity, the present research aims to investigate the impact of target parents‘ sexual orientation on heterosexuals’ judgment of parental competence in the German context. Since Germany is among the countries, in which the public opinion about LG people has improved most dramatically in recent decades (Pew Research Center 2013, 2020), it might provide an appropriate context to investigate whether persisting anti-LG attitudes today manifest in a covert form, as aversive or modern prejudice (Dovidio et al., 2017; McConahay, 1986).

Study 1 replicates Massey et al.’s (2013) restaurant vignette study and considers authoritarian versus authoritative parenting as a putative moderating factor. Study 2 examines the generalizability of the Study 1 results by applying a vignette taken from Barnhard et al. (2012), a study that was originally conducted without reference to LG parenthood, but investigated cross-cultural variation in the evaluation of different parenting styles. This vignette describes an everyday family conflict: the children want to play outside instead of doing their homework. It considers permissive parenting as a further detrimental parenting style and thus includes all three parenting styles, as postulated by Baumrind (1966).

Both Studies 1 and 2 also considered, in addition to the experimental variables, participants’ levels of traditional and modern homonegativity, and, for control purpose, participants’ tendencies toward socially desirable responding. Social desirability is always a concern when investigating anti-LG prejudice (Brown & Groscup, 2009; Hudson & Ricketts, 1980); however, it was not controlled for in the studies by Massey et al. (2013), Štrbić et al. (2019), and Tušl et al. (2020).

Hypothesis 1

Referring to the aversive prejudice framework (Dovidio et al., 2017), LG parents will be judged as least competent in parenting when showing negative parenting behavior, that is, authoritarian or permissive behavior compared to authoritative behavior.

Hypothesis 2

Referring to the conceptual proximity to aversive prejudice, modern homonegativity (McConahay, 1986) will be most negatively associated with parental competence attribution when LG parents show negative parenting behavior.

Hypothesis 3

Although the pattern as suggested in Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 may be attenuated by socially desirable responding, it will not disappear when including this variable for purpose of control.

Note that, in line with relevant previous vignette studies (see above), we expected the same pattern of results for lesbian and gay parents.

Pilot Studies

Although the vignettes we applied had already been used in previous research (Study 1 vignette: Massey et al., 2013; Study 2 vignette: Barnhard et al., 2012), they were both pretested in the German language versions. Participants of the pilot studies were students of advanced developmental psychology courses (Ns = 31 and 29) who were familiar with Baumrind’s (1966) typology of parenting styles; it was part of their course curriculum. The students were provided with the two (Pretest 1) or three vignettes (Pretest 2), and asked which of the three parenting styles was represented in which vignette. They were then asked to indicate the extent to which the description in the vignette captured the parenting style they had selected. Ratings were done on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 = very poorly to 4 = very well. This two-step pretesting approach was adopted from Barnhard et al. (2012). The Study 1 and 2 vignettes each were equal in word count (in German language). The parent couples described in the pretest vignettes were consistently heterosexual, and the acting parent was either the mother (Study 1 vignette) or the father (Study 2 vignette). The choice of names for the vignette protagonists were based on a norming study of 60 German first names (Rudolph et al., 2007). Parents’ names were chosen from the “classical” category, children’s names from the “modern” category; they each showed the same positive valence.

In agreement with the Ethical Principles of the German Psychological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie, 2016), neither the pilot studies nor the main studies required approval of an ethics committee. Each study was voluntary and anonymous. Participants were adults only. Participation was without compensation and could be terminated at any time without any reason or consequence. Participants were informed about the overall study purpose (evaluation of parental competence) before providing their informed consent. Upon request, by sending a separate e-mail message (to preserve anonymity), they were informed about the study results.

Pretest of the Study 1 Vignette

The students were asked to imagine the following family conflict situation: “You are sitting in a restaurant eating dinner. Across the room are a woman and a man sitting together with what looks to be a four-year-old child. (The child’s gender remained unknown; child in the German language, with its three genders, is a neutral noun). You notice that the two adults are holding hands. The woman, Kathrin, places her arm around the man, Thomas, and leans over and kisses him on the cheek. Then both parents take turns talking to the child. When their dinner arrives, Kathrin puts some food in a small colorful bowl and places it in front of the child. The child looks at it and frowns. All of a sudden, he/she picks up the bowl of food, throws it on the floor and starts screaming. Other people in the restaurant turn to look at them.” Then, the students were presented with two continuations of the situation, which were intended to reflect the target parent’s authoritarian versus authoritative parenting style.

Authoritarian

“Kathrin grabs the bowl off the floor and, in an angry raised voice, tells the child to be quiet and eat the dinner. The child picks up the bowl and starts throwing it again. Kathrin slaps the child’s hand and yells at her/him to put the bowl down on the table again. The child starts crying. Kathrin takes the child in her arms. It takes her several minutes to calm the child down. Kathrin is getting more and more frustrated by the child’s behavior. But eventually she gets him/her to sit back down at the table. Thomas places a new bowl of food in front of the child. Eventually the child begins eating on her/his own.”

Authoritative

“Kathrin lovingly takes the child in her arms and tries to calm him/her down. The child resists and screams: No! No! No! Kathrin is able to remain calm. She explains to the child in a sensitive but decisive tone that it is not okay to just throw your food on the floor, even if you don’t like it. She says you should always try it first to see if it might taste good. It takes her several minutes to calm the child down and get him/her to sit back down at the table. Thomas places a new bowl of food in front of the child. Eventually the child begins eating on her/his own.”

The findings indicated that all students but one selected the intended parenting style in both vignettes. The one deviating case concerned authoritative parenting, misclassified as permissive. Moreover, the students considered both vignettes representing the intended parenting style as well to very well (the deviating case was excluded from this analysis). Both representativeness scores were, on average, substantially above the scale midpoint of 2, indicating moderate representativeness. Effect sizes were very large. Table 1 (upper part) provides an overview of the piloting of the Study 1 vignette.

Pretest of the Study 2 Vignette

The students of the second pretest study (different from those of the first study) were asked to read three versions of a specific family conflict situation, involving Thomas and Kathrin (i.e., as in Study 1, the heterosexual parents), and their two children, seven-year-old Lea and eleven-year-old Felix. The three versions, this time given in the active father version, were intended to reflect the target parent’s authoritarian versus permissive versus authoritative parenting style.

Authoritarian

“Thomas and Kathrin believe that they know exactly what is best for their children. In Thomas and Kathrin’s opinion, children should always do what their parents expect of them. Neither questioning nor disobedience are allowed. One afternoon, Lea and Felix come home from school and want to go outside to play. When Thomas tells them that they have to finish all of their homework before they can go outside to play with their friends, Lea and Felix become upset. Thomas responds that there will be no further discussion on the matter, and the children have to listen to him and respect his authority.”

Permissive

“Thomas and Kathrin believe that parents should not put restrictions on their children and their development, and that while growing up, children should be free to do or not to do whatever they want. One afternoon, Lea and Felix come home from school and want to go outside to play. Thomas asks them if they have any homework to do, and Lea and Felix say that indeed they have homework but that they do not want to do it right now. They rather prefer playing outside. Thomas immediately agrees to his children’s plan and lets them go outside to play for as long as they want.”

Authoritative

“Thomas and Kathrin believe that parents should establish rules in the family, explain the reasoning, and encourage children to discuss their questions and concerns about those rules. One afternoon, Lea and Felix come home from school and want to go outside to play. When Thomas reminds them that they first need to do their homework before they can go outside to play with their friends, Lea and Felix become upset. Thomas listens to the children as they explain why they wanted to go outside first, and, ultimately, explains to the children the rules they had originally established which were clear that homework must be completed before going outside to play.”

All students selected the intended parenting style in each of the three vignettes. The students considered each vignette as an accurate representation of the intended parenting style. Again, average representativeness scores were well above the scale midpoint of 2, and, again, effect sizes were very large. Table 1 (lower part) provides an overview of the piloting of the Study 2 vignette. Taken together, both pilot studies justify labeling the vignettes used in terms of Baumrind’s parenting style typology.

Study 1

The first study used the restaurant vignette (Massey et al., 2013) to examine the interplay between target parents’ sexual orientation, gender, and parenting style (authoritarian vs. authoritative parenting) on heterosexual participants’ attribution of parental competence.

Method

Participants

Originally, the Study 1 sample consisted of 178 self-reported heterosexual individuals from Germany. Due to manipulation check failure, the sample size was slightly reduced to 170 participants (n = 108 women, n = 62 men). Their age ranged from 18 to 83 years (M = 35.02, SD = 17. 73). Almost all participants were born and raised in Germany; only 2 participants reported migration experience. About two third were in a stable partnership (64%) and one third were parents (36%). Educational level was above average; about two third of participants were seeking or holding a university degree (68%). Most participants were students (46%) or employed (38%). One third of participants claimed no religious affiliation (35%); all others belonged to a Christian denomination. In terms of political orientation (measured with a 7-point left-right scale, ranging from 0 = very left to 6 = very right), the majority placed themselves on the left side (scale points 0–2; 52%) or in the center (3; 41%) of the political spectrum, and only a minority placed themselves on the right side (4-5; 7%). Table 2 (left side) provides an overview of demographics.

Design

Study 1 used a three-factorial between-participants design. The first factor reflected target parent’s sexual orientation (LG vs. heterosexual), the second factor target parent’s gender (female vs. male), and the third factor target’s parenting style (authoritarian vs. authoritative).

With a total sample size of N = 170 participants, the statistical power of all F tests of the 2 × 2 × 2 design was 0.90, given a significance level of α = 0.05, and an assumed interaction effect of medium size, f = 0.25 (Cohen, 1988; power analyses according to Faul et al., 2007).

Procedure

To arrive at a diverse and large sample and thus to increase generalizability of findings and statistical power, respectively, participants were recruited using snowball sampling in social networks. Non-heterosexual orientation was an exclusion criterion, since this research focused on heterosexuals’ judgment of LG parenthood. After providing informed consent, participants were presented with one of the 8 possible restaurant vignettes and were asked to rate the target’s parental competence. Parents’ sexual orientation was indicated by the partners’ genders and names (lesbian condition: Kathrin and Anna; gay condition: Thomas and Alexander; heterosexual condition: Kathrin und Thomas) and their very intimate interaction (e.g., the partners were holding hands and kissed each other when sitting at the restaurant table). Participants then provided measures of homonegativity, social desirability, and demographics. As a manipulation check, participants were finally asked about the sexual orientation of the target parents presented in the vignette. Only participants who correctly recognized the parents as LG or heterosexual were included in the sample.

Measures

Parental competence

Participants evaluated the target’s parental competence using an 8-item measure developed by McLeod et al. (1999); German version by Kranz (2020). Specifically, participants were asked whether the target was a competent parent, responsible parent, nurturing parent, loving parent, and emotionally stable parent, whether she/he was sensitive to their child’s needs, spent quality time with their child, and was a suitable role model for their child. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = very much. Higher scores indicated a more positive evaluation of parental competence. Scale reliability was excellent (α = 0.96).

Homonegativity

Traditional homonegativity was measured with the 10-item Attitudes Toward LG People Short Scale (Herek, 1988; German version by Steffens, 2005). Items (e.g., “Lesbians are sick”, reversed: “Male homosexuality is a natural expression of sexuality”) were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = very much. Modern homonegativity was measured with the 9-item Denial of LG Discrimination Scale (Massey, 2009; modeled after McConahay’s, 1986, measure of modern racism). Items (e.g., “Most lesbians and gay men are no longer discriminated against”, reversed: “Lesbians and gay men often miss out on good jobs due to discrimination”) were rated on the same 5-point scale as traditional homonegativity. Reliabilities of both scales were good (αs = 0.80 and 0.86). Higher scores indicated greater homonegativity. Since the distribution of traditional homonegativity was heavily right-skewed, a log10 transformation was applied (Kline, 2009; Tabachnik & Fidell, 2013). The two homonegativity scales were moderately interrelated (r = 0.45, p < 0.001).

Social desirability

The Social Desirability Short Scale (Kemper et al., 2014; English version by Nießen et al., 2019) consisted of two 3-item subscales, tapping tendencies toward overstating positive qualities (PQ+ ; e.g., “Even if I am feeling stressed, I am always friendly and polite to others”) and minimizing negative qualities (NQ–; e.g., reversed: “I have occasionally thrown litter away in the countryside or on to the road”). Items were rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = very much. Reliabilities of both scales, with higher scores indicating greater social desirability, were low (αs = 0.54 and 0.60), but comparable to other studies (e.g., Götz et al., 2017; Roth & Altmann, 2019). Noteworthy, internal consistency is often limited for ultra-short measures as this one, in which items were selected to reflect the bandwidth of the underlying constructs. Adjusting for PQ+ and NQ– scale lengths by tripling the number of items (i.e., 9 items instead of 3, comparable to the length of the other scales used) would yield sufficient internal consistencies (αs = 0.78 and 0.82; Spearman-Brown formula). More importantly, Kemper et al. provided convincing evidence for the factorial and convergent/discriminant validity of their instrument. As expected, PQ+ and NQ– were moderately interrelated in the present study (r = 0.30, p < 0.001).

Results

Analysis of Variance

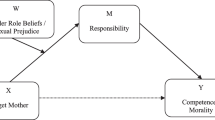

Parental competence attribution was submitted to a 2 (parent’s sexual orientation) × 2 (parent’s gender) × 2 (parenting style) between-participants analysis of variance (ANOVA). Figure 1 displays the means and standard errors for the different experimental conditions. The ANOVA explained two thirds of variance (\(R_{{{\mathrm{c}}}}^2\) = 0.67, p < 0.001). Specifically, two effects turned out to be significant. Not surprisingly, parenting style had a large impact on parental competence attribution (F1, 162 = 337.95, p < 0.001, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.68). Parents who interacted with their child in an authoritative way were perceived as more competent than parents who interacted with their child in an authoritarian way (Ms = 3.35 vs. 1.31, SEs = 0.08). Furthermore, the three-way interaction turned out to be statistically significant (F1, 162 = 7.86, p = 0.006, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.05). To understand this interaction, separate 2 (parent’s sexual orientation) × 2 (parent’s gender) ANOVAS were conducted for each parenting style. Only with regard to authoritarian parenting, the two-way interaction was statistically significant. As pairwise comparisons showed, heterosexual authoritarian fathers were attributed less parental competence than heterosexual authoritarian mothers (Ms = 0.99 vs. 1.55, SEs = 0.14 and 0.15, p = 0.027). Regarding authoritative parenting, neither main effect nor interaction effects achieved statistical significance.

We repeated the ANOVA and included participants’ gender and social desirability as covariates (which did not achieve statistical significance): The large impact of parenting style on parental competence attribution remained unchanged (F1, 159 = 325.10, p < 0.001, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.67), and the significant three-way interaction remained weak (F1, 159 = 7.29, p = 0.008, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.04).

Correlation Analysis

We then analyzed whether traditional and/or modern homonegativity were associated with the attribution of parental competence to LG parents. We first inspected bivariate correlation coefficients separately for the two parenting conditions. To avoid spurious effects due to experimentally induced level differences in parental competence attributions, we used mean-centered instead of raw values (i.e., experimental condition means of parental competence attribution were subtracted from participants’ individual scores). Only one of the four possible correlations turned out to be statistically significant. The higher participants’ traditional homonegativity, the less competence they attributed to authoritative LG parents (r = −0.42, p = 0.004).

We finally regressed the attribution of LG parental competence on traditional and modern homonegativity, while controlling for participants’ gender and social desirability. Again, analyses were conducted separately for authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Reflecting the bivariate correlations, only the regression analysis for the authoritative parenting condition was statistically significant (\(R_{{{\mathrm{c}}}}^2\) = 0.16, p = 0.032). Only traditional homonegativity contributed to explaining variance in parental competence attribution (β = −0.49, p = 0.010).

Summary

Results of Study 1 contradicted both hypotheses. LG parents were not perceived as less competent in parenting when showing authoritarian behavior toward their child. In this condition, neither participants’ traditional nor, as expected, modern homonegativity predicted the devaluation of LG parents’ competence.

Study 2

The second study used the homework vignette (Barnhard et al., 2012) to examine the interplay between target parents’ sexual orientation, gender, and parenting style on heterosexual participants’ attribution of parental competence. Study 2 intended to generalize Study 1 findings in some aspects. Compared to the Study 1 vignette, the Study 2 vignette depicted parents’ interaction with two older children (school children instead of a preschooler; siblings instead of a single child) and considered all three parenting styles proposed by Baumrind (1966; authoritarian vs. permissive vs. authoritative parenting).

Method

Participants

The original Study 2 sample consisted of 300 self-reported heterosexual individuals from Germany. Due to manipulation check failure, the sample size was slightly reduced to 290 participants (n = 192 women, n = 98 men). They were 18 to 83 years old (M = 36.68, SD = 16. 84). About two third of participants were in a stable partnership (68%) and almost one half had children (42%). Educational level was above average; about two third of participants were seeking or holding a university degree (64%). Most participants were employed (51%) or students (32%). The majority were born and raised in Germany; 13 participants reported migration experience. A considerable proportion of participants claimed no religious affiliation (41%); all others, except of two Buddhists, identified as Christian. In terms of political orientation (the same measure as in Study 1), the majority placed themselves on the left side (62%) or in the center (31%) of the political spectrum, and only a minority placed themselves on the right side (7%). Table 2 (right side) provides an overview of demographics.

Design

As Study 1, Study 2 used a three-factorial between-participants design. The first factor reflected target parent’s sexual orientation (LG vs. heterosexual), the second factor target parent’s gender (female vs. male), and the third factor target’s parenting style, this time with three conditions (authoritarian vs. permissive vs. authoritative). Given the total sample size of N = 290 participants, the statistical power of all F tests of the 2 × 2 × 3 design was 0.97 (α = 0.05, f = 0.25).

Procedure

The Study 2 procedure corresponded to the Study 1 procedure, except that there were three instead of two vignette versions describing a family conflict. After providing informed consent, participants were presented with the vignette. Again, parents’ names (same names as in Study 1) and gender pronouns indicated their sexual orientation. And again, participants were asked to rate the target’s parental competence. Then, participants provided measures of homonegativity, social desirability, and demographics. Finally, a manipulation check of target parents’ sexual orientation was conducted.

Measures

The measures used in Study 2 were the same as in Study 1. Scale reliabilities and interrelations were very comparable. Reliabilities were excellent for parental competence (α = 0.91), good for traditional and modern homonegativity (with the former scale again log10 transformed; αs = 0.85 and 0.87; r = 0.39, p < 0.001), and relatively poor for the social desirability tendencies to overstate positive and minimize negative qualities (PQ+ and NQ−; αs = 0.60 and 0.56; r = 0.28, p < 0.001).

Results

Analysis of variance

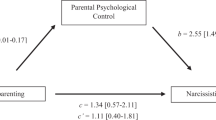

Parental competence attribution was submitted to a 2 (parent’s sexual orientation) × 2 (parent’s gender) × 3 (parenting style) between-participants analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means and standard errors for the different experimental conditions are illustrated in Fig. 2. The ANOVA explained about one third of variance in parental competence (\(R_{{{\mathrm{c}}}}^2\) = 0.35, p < 0.001). Specifically, two effects turned out to be significant. First, there was a small but statistically significant main effect of parent’s sexual orientation (F1, 278 = 4.62, p = 0.033, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.02). Surprisingly, LG parents were perceived as somewhat more competent than heterosexual parents (Ms = 2.48 vs. 2.29; SEs = 0.06). Second, parenting style had a large impact on parental competence attribution (F2, 278 = 70.72, p < 0.001, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.34). All pairwise comparisons were statistically significant (ps < 0.001). Parents who interacted with their child in an authoritative way were perceived as more competent than parents who interacted in a permissive way, and parents showing authoritarian behavior were perceived as least competent (Ms = 3.12 vs. 2.23 vs. 1.81; SEs = 0.08).

As in Study 1, we repeated the ANOVA controlling for participants’ gender and social desirability. Again, the covariates did not turn out as statistically significant. The large effect of parenting style (F1, 275 = 68.61, p < 0.001, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.67) remained unchanged, as did the weak main effect of sexual orientation (F1, 275 = 4.52, p = 0.034, \({\upeta}_{{{\mathrm{p}}}}^2\) = 0.02).

Correlation analysis

We finally analyzed associations between traditional and modern homonegativity and the attribution of parental competence to LG parents. Again, we first inspected correlation coefficients separately for the three parenting conditions. Only one of the six possible correlations turned out to be statistically significant. The higher participants’ modern homonegativity, the less competence they attributed to authoritative LG parents (r = −0.35, p = 0.019).

We then regressed the attribution of LG parental competence on traditional and modern homonegativity, while controlling for participants’ gender and social desirability. Again, analyses were conducted separately for the parenting conditions. Reflecting the bivariate correlations, only the regression analysis for the authoritative parenting condition was statistically significant (\(R_{{{\mathrm{c}}}}^2\) = 0.25, p = 0.006). Apart from gender (lower attribution values for male participants; β = −0.30, p = 0.036) and social desirability (namely, the tendency of overstating positive qualities; β = 0.38, p = 0.030), only modern homonegativity contributed to explaining variance in the attribution of parental competence to LG parents (β = −0.36, p = 0.034).

Summary

Replicating Study 1, results of Study 2 contradicted both hypotheses. LG parents showing authoritarian or permissive behavior toward their child were not perceived as less competent than heterosexual parents showing such detrimental parenting behavior. In the authoritarian or permissive parenting conditions, neither participants’ traditional nor, as expected, modern homonegativity predicted the devaluation of LG parents’ competence.

Discussion

Neither Study 1 nor Study 2 revealed a general disadvantage for LG compared to heterosexual parents in the social judgment of parental competence. Admittedly, we did not expect such a main effect of target sexual orientation in Germany––a context of some societal consensus about, or, put more skeptically, pressures toward the acceptance of LG people. Referring to the aversive prejudice framework (Dovidio et al., 2017), a member of a specific (here, non-heterosexual) outgroup should only be discriminated against when showing some weakness. Under such condition, one can rationalize one’s discrimination and thus maintain a non-prejudiced self-view and/or public image. Correspondingly, we hypothesized less parental competence attribution to LG compared to heterosexual parents if showing authoritarian or permissive parenting, lacking either responsiveness or demandingness––one of the two core dimensions of positive parenting. In contrast, if showing authoritative parenting, characterized by high responsiveness and high demandingness, LG and heterosexual targets should be equally attributed with high parental competence. Contrary to this hypothesis, however, we did not find the expected interaction of target sexual orientation and parenting behavior. Thus far, our results are similar to those found in the Croatian (Štrbić et al., 2019) and Czech context (Tušl et al., 2020). Since the US study (Massey et al., 2013) did not test the two-way interaction, respective findings cannot be compared.

For the sake of completeness, it should be said that we also did not find the devaluation of LG parents in specific constellations of target gender and parenting style. We had no specific hypothesis about such three-way interaction, but it would have not been entirely implausible, since both sexual orientation and parenting style are gendered. LG people are stereotypically perceived, and derogated, as gender inverted. As many anti-LG slurs attest, lesbians are often perceived as more masculine and gay men as more feminine than their heterosexual counterparts (Blashill & Powlishta, 2009; Carnaghi et al., 2011). Regarding parenting style, mothers are stereotypically perceived as more authoritative than fathers, whereas fathers are perceived as more authoritarian than mothers (McKinney & Renk, 2008; Russel et al., 1998; for a review, see Yaffe 2020). This fits general gender norms of femininity and masculinity; women are expected to be warm and caring, whereas men are expected to be dominant and strict (Eckes, 2002; Fiske, 2017). Previous research has shown that LG people displaying gender inverted behavior are discriminated more against than LG people displaying gender congruent behavior (Allen & Smith, 2011; Lehavot & Lambert, 2007). Therefore, lesbian mothers could have been attributed with lower parental competence if showing masculine-authoritarian parenting and, likewise, gay fathers if showing feminine-authoritative parenting. This, however, was not the case.

The three-way interaction we found in Study 1, but not in Study 2, concerned gender differences in the heterosexual target by authoritarian parenting constellation. Heterosexual fathers who responded in an authoritarian way to their little child’s misbehavior were attributed less parental competence than heterosexual authoritarian mothers. We interpret this finding as consistent with the ideal of new fatherhood, according to which today’s (heterosexual) fathers are expected to take on a greater role in meeting the emotional and relational needs of their children––a traditionally maternal task (Lamb, 2000; Marsiglio & Roy, 2012). In other words, the ideal of the authoritarian father––as, in the German context, personified by the Prussian “Soldier King” Frederick William I (1688–1740), the father of Frederick II (“the Great, 1712–1786; MacDonogh 2000)––has had its day. Nowadays, the vast majority of Germans, like most people from other Western countries, refuse the stern father figure and rather esteem caring masculinities (Elliott, 2016; see also Knight & Brinton, 2017)

Close to the concept of aversive prejudice is that of modern prejudice (McConahay, 1986). Both concepts have in common that prejudice today often comes in a subtle or hidden way. It is either expressed through rationalization or through denial that societal discrimination against a specific outgroup still goes on, which, in turn, immunizes oneself, as part of the putatively tolerant society, against appearing prejudiced. Following the latter line of theorizing, we assessed both, participants’ level of modern and traditional homonegativity. Consistent with previous research (Adolfsen et al., 2010; Konopka et al., 2020; Massey, 2008), both aspects of homonegativity were moderately positively interrelated. Contrary to our second hypothesis, however, neither in Study 1 nor in Study 2, modern homonegativity was (negatively) associated with the evaluation of LG parental competence in situations, when LG target parents interacted with their children in an authoritarian or permissive way––that is, when prejudice could easily have been rationalized. Interestingly, traditional homonegativity (Study 1) and modern homonegativity (Study 2) were significantly negatively related to the social judgment of LG parents showing authoritative behavior, that is, the most positive parenting style. We find this pattern difficult to explain. That said, results involving traditional homonegativity should be interpreted with some caution; the respective measure was heavily right-skewed, indicating a floor effect.

According to our third hypothesis, socially desirable responding was expected to reduce but not eliminate the pattern of subtle or hidden homonegativity in the social perception of LG parenthood, as predicted by Hypothesis 1 and 2. Since the predicted pattern did not occur, it could not be attenuated by social desirability. Neither the social desirability tendency to overstate one’s positive qualities nor the tendency to minimize one’s negative qualities (PQ+ or NQ−) had any impact on the (insignificant) interaction effect of parents’ sexual orientation and parenting style on parental competence attribution. Furthermore, neither of the social desirability tendencies had any impact on the (again, insignificant) correlation between modern homonegativity and attribution of parental competence to LG parents showing detrimental interaction with their children. Apparently, social desirability was no great issue in the present research. This conclusion is reinforced when inspecting the overall correlations between social desirability (PQ+ vs. NQ−) and either traditional or modern homonegativity. Only one of the four correlations turned out to be statistically significant: the correlation between NQ− and modern homonegativity. Participants who tended to minimize their negative qualities were more likely to deny the existence of anti-LG discrimination. The overall negligible role of social desirability in the present research might be due to two factors: the indirect vignette approach (Walzenbach, 2019) combined with anonymous online research (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007).

In sum, the consistent Study 1 and Study 2 results fit into previous research that did not find any evidence for a social perception disadvantage of LG parenthood (Camilleri & Ryan, 2006; Di Battista et al., 2021; Kranz, 2020, 2022; Massey, 2008; McCutcheon & Morrison, 2015; Štrbić et al., 2019; Tušl et al., 2020). Importantly, the statistical power of our studies met the typically recommended level (0.80, according to Cohen, 1988); that is, the chance of finding the hypothesized interaction effect, if it existed, was sufficient. How can we explain the equality in parental competence attributions, irrespective of parenting behavior? We propose four lines of arguments that do not exclude each other. The first deals with sample characteristics, the second with LG attitudes in today’s Germany, the third with homonormativity, and the forth with the predominant impact of parenting style.

First, the representativity of findings might be questioned because our sample deviated from the general population in important aspects. It was more female, younger, better educated2, and politically more left-wing oriented3––factors that are typically negatively associated with homonegativity (Herek & McLemore, 2013; Walch et al., 2010; for the German context, see Küpper et al., 2017). Regarding religious affiliation, a factor that is also (positively) associated with homonegativity (Finlay & Walther, 2003; Whitley, 2009), the present sample was not exceptional4.

Second, Germany has become a very LG friendly country over the last decades, especially when considering the persecution of LG people during the Nazi regime (Grau, 2012; Plant, 2011), but also until the 1960s (at least in West Germany; Moeller, 1994; for the situation of LG people in East Germany, see Sweet, 1995). Today, a vast majority of the German population says that society should accept homosexuality (86%; Pew Research Center, 2020) and that LG people should have the same rights as heterosexuals (88%; European Commission, 2019). Among 34 countries worldwide and the 28 countries of the European Union, respectively, these percentages are at the top and higher than in all other countries where the previous vignette studies on LG parenthood were conducted (i.e., Australia, Canada, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Italy, Portugal, and the United States). Most Germans support the “marriage for all” (84%; European Commission, 2019) and equal opportunities for adoption (73%; Decker & Brähler, 2020). A majority of Germans says that LG people have the same (61%) or even more (3%) parental competence than heterosexuals (YouGov Deutschland, 2017). Against this background, the equal judgement of LG and heterosexual parental competence is less surprising––especially, when considering the specific sample characteristics discussed above.

A third possible explanation for the equal attribution of parental competence to LG and heterosexual parents involves homonormativity (Duggan, 2002), that is, the increasing assimilation of straight norms into queer culture. The legalization of LG partnerships including full adoption rights might have both benefitted from and reinforced this trend. From a critical point of view, LG life has become privatized and domesticated. Possibly, the vignettes we used in the present research reflected such homonormativity. We depicted nuclear families, LG parent couples with their children, who enjoyed, and could afford, a family restaurant visit and valued school education. Hence, it might be less surprising that LG targets conforming to conventional middle-class standards were judged as parentally competent as their heterosexual counterparts. Homonormativity, however, might produce new forms of exclusion, both outside and within the queer community (Halberstam, 2011). What about the social perception of queer parents who do not want to or cannot conform to homonormativity (e.g., separated, poor, or nonbinary queer parents; see also Fish & Russell, 2018)?

A fourth possible reason for the equal attribution of parental competence to LG and heterosexual parents is the very large effect of parenting behavior––an effect that might predominate any effect of sexual orientation, if existing at all. The variation of parenting behavior explained two third (Study 1) and one third (Study 2) of variance in parental competence attribution. Although not the focus of the present study, this result deserves some attention. It can be interpreted in the sense of manipulation check. We intended – and succeeded – to vary the valence of parenting style. Authoritative parenting should indicate positive parenting, whereas authoritarian and permissive parenting should indicate comparatively negative parenting. The judgment of parental competence, as an indicator of positive parenting perception, affirmed this intention. Authoritative parenting was associated with highest parental competence attribution. Interestingly, there was a striking difference in the social judgment of authoritarian versus permissive parenting; the latter was judged more positively than the former. In other words, authoritarian and permissive parenting are not equally detrimental.

Again, the German context should be taken into account to understand this rank order of parenting styles. After World War II, the world wondered how the Nazi regime and its unprecedented atrocities could have been possible. The Frankfurt School answered the question by proposing the concept of authoritarian personality, a personality style characterized by submission to authority, conventionalism, rigidity, and oppression of subordinate people (Adorno et al., 1950; Fromm, 1941). This concept was highly influential in Western postwar societies. It was not until the 1968 Revolution in West Germany that the younger people rebelled against the authoritarianism of their parent generation and propagated a liberal lifestyle. At that time, the idea of anti-authoritarian parenting became very popular, both in academia and wider society (Baader, 2010; Brown, 2013). In East Germany, another authoritarian regime came to power after World War II. The East Germans then won their freedom in 1989 in the collapse of the German Democratic Republic. Whether in the western or eastern part of reunified Germany, anti-authoritarian parenting is an ideal of only a minority today, but certainly authoritarian parenting has fallen largely out of favor (although, there still exist differences between former East and West Germany; Döge & Keller, 2014; Uhlendorff, 2001). This historical sketch might explain the rank order of parenting styles we found. Importantly, the preference of permissive over authoritarian parenting is not culturally invariant. Societies of Western, South, and East Asia, for example, estimate authoritarian parenting more than permissive parenting (Albert et al., 2007; Rindermann et al., 2013; cf. Bornstein, 2012).

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

The present research contributes to the literature in several ways. (1) It refers to processes of subtle or hidden prejudice when investigating the social judgment of LG parenthood. (2) It considers the interplay of sexual orientation and parenting style; regarding the latter, it includes one vignette condition with a clearly positive parenting style and two conditions with comparatively negative parenting styles. (3) Whether the vignettes indicated the different parenting styles as intended, was thoroughly tested and proven in a pilot study. (4) Study 1 replicated previous studies conducted in the United States, Croatia, and the Czech Republic; the findings were very similar to those found in the two other European countries. (5) The present research used two vignettes to assess the generalizability of results; both vignettes described a family conflict situation, each with a different topic, and a different sex/age of the children. The findings were consistent across both studies. (6) Finally, the present research considered and controlled for participants’ individual homonegativity and social desirability.

The present research also has some limitations that can inform future research. (1) The main limitation concerns sampling. The majority of the study participants were female, young, highly educated, and politically center-left oriented. Whether similar results would emerge in a more masculine, older, less educated, and more right-oriented sample, needs further investigation. Future research should therefore pay more attention to recruit heterogeneous samples in terms of the demographics listed above. (2) Moreover, it would be of some interest to investigate the impact of sexual orientation and parenting style on the social perception of LG parenthood in a cross-cultural setting. Future research might compare cultural contexts that differ on the liberalism-conservatism continuum and related attitudes toward homosexuality, such as Western- and Eastern-European countries (Pew Research Center, 2020; Stankov et al., 2014). (3) Due to its factorial design, the vignette approach allows for causal inferences, which is certainly a strength (Alexander & Becker, 1978). Nevertheless, social judgments in real life situations can diverge from those in imagined situations. Future research should therefore examine the interaction of sexual orientation and parenting style on the evaluation of real instead of fictive couples. Note however, that this approach requires careful controlling for social distance between participants and target couples.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our research has some theoretical and practical implications. It shows remarkable convergence between the social evaluation of different parenting styles and their adaptive value as found in previous parenting research (for a meta-analysis, see Pinquart & Kauser, 2018). Our research thus suggests that people know what is good for kids: an authoritative parenting style that combines parents’ high levels of both responsiveness and demandingness. Importantly, such estimation of authoritative parenting was independent from parents’ sexual orientation, which converges with previous research as well (for a meta-analysis, see Fedewa et al., 2015). Our research underlines the importance of disseminating empirical evidence from the scientific community to the public. Furthermore, it reinforces policymakers to advocate for the best interests of the child (e.g., in foster care and adoption proceedings) while avoiding any sexual discrimination against the parents. Such policy seems to have remarkable public approval––and tremendously helps LG people in the transition to parenthood (Leal et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Two vignette studies conducted in the German context displayed that LG parents were judged as competent in parenting as heterosexual parents, irrespective of whether the parents showed a beneficial, authoritative parenting style (with high levels of both demandingness and responsiveness) or a detrimental parenting style, either authoritarian (high demandingness, low responsiveness) or permissive (high responsiveness, low demandingness). Contrary to the aversive prejudice framework, LG parents were not discriminated against when showing ambivalent parenting behavior. The data thus confirm broad acceptance of rainbow families in contemporary Germany and also show an impressive consensus to estimate authoritative parenting and to devaluate permissive and especially authoritarian parenting.

Endnotes

1. A note on terms: While homophobia (Weinberg, 1972) is a well-known and widely used term in both common and scientific language, there are many reasons for scrapping it (Herek, 2004). Most importantly, the literal meaning is fear of homosexuality or LG people, which seems inadequate to describe anti-LG attitudes and/or behavior. Therefore we use the term homonegativity (Hudson & Ricketts, 1980) throughout the paper.

2. According to the German Federal Statistical Office (Deutsches Statistisches Bundesamt, 2021), the proportion of females in Germany is 51% (65% in the present research; averaged across Studies 1 and 2); the mean age is 44.25 years (36.07 years in the present research), the proportion of highly educated is 32% (65% in the present research).

3. Taking the representative German data set from the European Social Survey (2018), the proportion of participants placing themselves on the left side (1–4)/in the center (5–7)/on the right side (8–11) of the 11-point left-right scale was 30/59/11%. That is, participants in the present research (Studies 1 and 2) were more left-wing oriented (58%), but less center-oriented (35%) and less right-wing orientated (7%).

4. According to the Research Group World Views Germany (Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauungen in Deutschland, 2019), 39% of Germans are without religious affiliation (exactly the same percentage in the present research).

Change history

22 July 2022

The endnotes were placed after Conclusion section.

References

Abou-Chadi, T., & Finnigan, R. (2019). Rights for same-sex couples and public attitudes toward gays and lesbians in Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 52(6), 868–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018797947.

Adamczyk, A., & Liao, Y. C. (2019). Examining public opinion about LGBTQ-related issues in the United States and across multiple nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022332.

Adolfsen, A., Iedema, J., & Keuzenkamp, S. (2010). Multiple dimensions of attitudes about homosexuality: Development of a multifaceted scale measuring attitudes toward homosexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(10), 1237–1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2010.517069.

Adorno, T., Frenkel-Brunswick, E., Levinson, D., Sanford, N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. Harper.

Aksoy, C. G., Carpenter, C. S., De Haas, R., & Tran, K. (2018). Do laws shape attitudes? Evidence from same-sex relationship recognition policies in Europe. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id_3229801.

Albert, I., Trommsdorff, G., & Mishra, R. (2007). Parenting and adolescent attachment in India and Germany. In G. Zheng, K. Leung, & J. Adair (Eds.), Perspectives and progress in contemporary cross-cultural psychology (Selected papers from the 17th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology) (pp. 97–108). China Light Industry Press.

Alexander, C. S., & Becker, H. J. (1978). The use of vignettes in survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 42(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1086/268432.

Allen, J., & Smith, J. L. (2011). The influence of sexuality stereotypes on men’s experience of gender-role incongruence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 12(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019678.

Baader, M. S. (2010). Historische Bildungsforschung als Erinnerungsarbeit: 68 und die Pädagogik [Historical educational research as memory work: 68 and pedagogics]. In C. Dietrich, & H.-R. Müller (Eds.). Die Aufgabe der Erinnerung in der Pädagogik [The task of memory work in pedagogics] (pp. 209−225). Klinkhardt.

Baiocco, R., Nardelli, N., Pezzuti, L., & Lingiardi, V. (2013). Attitudes of Italian heterosexual older adults towards lesbian and gay parenting. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10(4), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-013-0129-2.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence. Beacon.

Barnhart, C. M., Raval, V. V., Jansari, A., & Raval, P. H. (2013). Perceptions of parenting style among college students in India and the United States. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 684–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9621-1.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611.

Blashill, A. J., & Powlishta, K. K. (2009). Gay stereotypes: the use of sexual orientation as a cue for gender-related attributes. Sex Roles, 61(11), 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9684-7.

Bornstein, M. H. (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting, 12(2-3), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.683359.

Brown, G. (2012). Homonormativity: a metropolitan concept that denigrates “ordinary” gay lives. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(7), 1065–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.699851.

Brown, M. J., & Groscup, J. L. (2009). Homophobia and acceptance of stereotypes about gays and lesbians. Individual Differences Research, 7(3), 159–167.

Brown, T. S. (2013). West Germany and the global sixties: The anti-authoritarian revolt 1962-1978. Cambridge University Press.

Camilleri, P., & Ryan, M. (2006). Social work students’ attitudes toward homosexuality and their knowledge and attitudes toward homosexual parenting as an alternative family unit: An Australian study. Social Work Education, 25(3), 288–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470600565244.

Carnaghi, A., Anderson, J., & Bianchi, M. (2018). On the origin of beliefs about the sexual orientation and gender-role development of children raised by gay-male and heterosexual parents: An Italian Study. Men and Masculinities. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X18775462

Carnaghi, A., Maass, A., & Fasoli, F. (2011). Enhancing masculinity by slandering homosexuals: the role of homophobic epithets in heterosexual gender identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(12), 1655–1665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211424167.

Clarke, V. (2001). What about the children? Arguments against lesbian and gay parenting. Women’s Studies International Forum, 24(5), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5395(01)00193-5.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum.

Crawford, I., & Solliday, E. (1996). The attitudes of undergraduate college students toward gay parenting. Journal of Homosexuality, 30(4), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v30n04_04.

Decker, O., & Brähler, E. (Eds.) (2020). Leipziger Autoritarismus-Studie 2020. Autoritäre Dynamiken: Alte Ressentiments - neue Radikalität [Leipzig Authoritarianism Study 2020. Authoritarian dynamics: Old resentments - new radicalism]. https://www.boell.de/de/leipziger-autoritarismus-studie

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie (2016). Berufsethische Richtlinien [Ethical principles]. http://www.dgps.de/fileadmin/documents/Empfehlungen/berufsethische_richtlinien_dgps.pdf.

Deutsches Statistisches Bundesamt (2021). Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht [Population split by nationality and sex]. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/zensus-geschlecht-staatsangehoerigkeit-2020.html.

Di Battista, S., Paolini, D., & Pivetti, M. (2021). Attitudes toward same-sex parents: Examining the antecedents of parenting ability evaluation. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 17(3), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2020.1835596.

Döge, P., & Keller, H. (2014). Child-rearing goals and conceptions of early childcare from young adults’ perspective in East and West Germany. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 19(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2012.692657.

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Quaranta, M. (2020). Let them be, not adopt: General attitudes towards gays and lesbians and specific attitudes towards adoption by same-sex couples in 22 European countries. Social Indicators Research, 150, 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02291-1.

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2000). Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science, 11(4), 319–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00262.

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Pearson, A. R. (2017). Aversive racism and contemporary bias. In F. K. Barlow & C. G. Sibley (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the psychology of prejudice (pp. 267–294). Cambridge University Press.

Duggan, L. (2002). The new homonormativity: The sexual politics of neoliberalism. In R. Castronovo & D. D. Nelson (Eds.), Materialising democracy: Towards a revitalized cultural politics (pp. 175–194). Duke University Press.

Eckes, T. (2002). Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: testing predictions from the stereotype content model. Sex Roles, 47(3), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021020920715.

Elliott, K. (2016). Caring masculinities: Theorizing an emerging concept. Men and Masculinities, 19(3), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X15576203.

European Commission (2019). Eurobarometer on discrimination 2019: The social acceptance of LGBTI people in the EU. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/ebs_493_data_fact_lgbti_eu_en-1.pdf

European Social Survey (2018). ESS9-2018-1.1. European Social Survey Data Archive at the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. http://nesstar.ess.nsd.uib.no/webview

Farr, R. H., Bruun, S. T., & Patterson, C. J. (2019). Longitudinal associations between coparenting and child adjustment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parent families. Developmental Psychology, 55(12), 2547–2560. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000828.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Fedewa, A. L., Black, W. W., & Ahn, S. (2015). Children and adolescents with same-gender parents: a meta-analytic approach in assessing outcomes. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 11, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.869486.

Finlay, B., & Walther, C. S. (2003). The relation of religious affiliation, service attendance, and other factors to homophobic attitudes among university students. Review of Religious Research, 44(4), 370–393. https://doi.org/10.2307/3512216.

Fish, J. N., & Russell, S. T. (2018). Queering methodologies to understand queer families. Family Relations, 67(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12297.

Fiske, S. T. (2017). Prejudices in cultural contexts: Shared stereotypes (gender, age) versus variable stereotypes (race, ethnicity, religion). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 791–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617708204.

Flores, A. R., & Barclay, S. (2016). Backlash, consensus, legitimacy, or polarization: the effect of same-sex marriage policy on mass attitudes. Political Research Quarterly, 69(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912915621175.

Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauungen in Deutschland (2020). Religionszugehörigkeiten 2019 [Religious affiliations 2019]. https://fowid.de/meldung/religionszugehoerigkeiten-2019

Fromm, E. (1941). Escape from freedom. Rinehart.

Gato, J., & Fontaine, A. M. (2013). Anticipation of the sexual and gender development of children adopted by same-sex couples. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.645484.

Gato, J., & Fontaine, A. M. (2016a). Attitudes toward adoption by same-sex couples: Effects of gender of the participant, sexual orientation of the couple, and gender of the child. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2015.1049771.

Gato, J., & Fontaine, A. M. (2016b). Predicting Portuguese psychology students’ attitudes toward the psychological development of children adopted by lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(11), 1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1223316.

Gato, J., & Fontaine, A. M. (2017). Predicting attitudes toward lesbian and gay parent families among Portuguese students from helping professions. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2016.1268232.

Gerhards, J. (2010). Non-discrimination towards homosexuality: The European Union’s policy and citizens’ attitudes towards homosexuality in 27 European countries. International Sociology, 25(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580909346704.

Götz, F. M., Stieger, S., & Reips, U. D. (2017). Users of the main smartphone operating systems (iOS, Android) differ only little in personality. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0176921 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176921.

Grau, G. (2012). Hidden Holocaust? Gay and lesbian persecution in Germany 1933−1945. Routledge.

Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. Duke University Press.

Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25(4), 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498809551476.

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: thinking about sexual stigma and prejudice in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1(2), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6.

Herek, G. M., & McLemore, K. A. (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826.

Hoffarth, M. R., & Hodson, G. (2014). Is subjective ambivalence toward gays a modern form of bias? Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.014.

Hudson, W., & Ricketts, W. A. (1980). A strategy for measurement of homophobia. Journal of Homosexuality, 5(4), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v05n04_02.

Kemper, C. J., Beierlein, C., Bensch, D., Kovaleva, A., & Rammstedt, B. (2014). Soziale Erwünschtheit-Gamma (KSE-G) [Social Desirability-Gamma Short Scale (KSE-G)]. GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.6102/zis186

Kleinert, E., Martin, O., Brähler, E., & Stöbel-Richter, Y. (2015). Motives and decisions for and against having children among nonheterosexuals and the impact of experiences of discrimination, internalized stigma, and social acceptance. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.838745.

Kline, R. B. (2009). Becoming a behavioral science researcher: A guide to producing research that matters. Guilford.

Konopka, K., Prusik, M., & Szulawski, M. (2020). Two sexes, two genders only: Measuring attitudes toward transgender individuals in Poland. Sex Roles, 82(9), 600–621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01071-7.

Kranz, D. (2020). The impact of sexual and gender role orientation on heterosexuals’ judgments of parental competence and adoption suitability. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(3), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000382.

Kranz, D. (2022). The attribution of parental competence to lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples: Experimental and correlational results. Journal of Homosexuality, 69(7), 1252–1274. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1909395.

Knight, C. R., & Brinton, M. C. (2017). One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. American Journal of Sociology, 122(5), 1485–1532. https://doi.org/10.1086/689814.

Küpper, B., Klocke, U., & Hoffmann, L. C. (2017): Einstellungen gegenüber lesbischen, schwulen und bisexuellen Menschen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Umfrage [Attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in Germany. Results of a representative survey]. Nomos.

Lamb, M. E. (2000). The history of research on father involvement: An overview. Marriage & Family Review, 29(2-3), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v29n02_03.

Leal, D., Gato, J., Coimbra, S., Freitas, D., & Tasker, F. (2021). Social support in the transition to parenthood among lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons: A systematic review. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00517-y

Lehavot, K., & Lambert, A. J. (2007). Toward a greater understanding of antigay prejudice: On the role of sexual orientation and gender role violation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701503390.

MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.19.

MacDonogh, G. (2000). Frederick the Great: A life in deed and letters. St. Martin’s.

Marsiglio, W., & Roy, K. (2012). Nurturing dads: Social initiatives for contemporary fatherhood. SAGE.

Massey, S. G. (2008). Sexism, heterosexism, and attributions about undesirable behavior in children of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual parents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 3(4), 457–483. https://doi.org/10.1300/J461v03n04_05.

Massey, S. G. (2009). Polymorphous prejudice: liberating the measurement of heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 56(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360802623131.

Massey, S. G., Merriwether, A. M., & Garcia, J. R. (2013). Modern prejudice and same-sex parenting: shifting judgments in positive and negative parenting situations. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.765257.

McConahay, J. B. (1986). Modern racism, ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale. In J. F. Dovidio & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 91–125). Academic Press.

McCutcheon, J., & Morrison, M. A. (2015). The effect of parental gender roles on students’ attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive couples. Adoption Quarterly, 18(2), 138–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926755.2014.945702.

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008). Differential parenting between mothers and fathers: Implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6), 806–827. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07311222.

McLeod, A., Crawford, I., & Zechmeister, J. (1999). Heterosexual undergraduates’ attitudes toward gay fathers and their children. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 11(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v11n01_03.

Moeller, R. G. (1994). The homosexual man is a “man,” the homosexual woman is a “woman”: Sex, Society, and the law in postwar West Germany. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 4(3), 395–429.

Moreno, K. N., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2001). Intergroup affect and social judgment: feelings as inadmissible information. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 4(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430201041002.

Morrison, M. A., & Morrison, T. G. (2002). Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. Journal of Homosexuality, 43(2), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v43n02_02.

Morse, C. N., McLaren, S., & McLachlan, A. J. (2007). The attitudes of Australian heterosexuals toward same-sex parents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 3(4), 425–455. https://doi.org/10.1300/J461v03n04_04.