Abstract

Objectives

Worldwide, depression is one of the most common medical disorders in adolescence. Adolescent depressive symptoms generally increase over time, but many experience decreases after an initial peak. The purpose of this paper was to examine ecological predictors of baseline and change in adolescent depressive symptoms using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a framework.

Methods

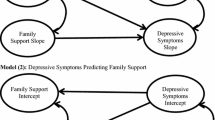

Adolescents (n = 500; 52% female; baseline age 10–13 years) and their parents living in the northwestern United States completed annual questionnaires over six years. A structural equation model growth curve analysis was conducted to examine how family stressors, neighborhood safety, parent-child connectedness, and youth locus of control predicted adolescent depressive symptoms (baseline and growth).

Results

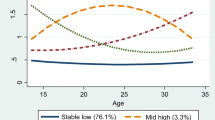

Results demonstrated that adolescent locus of control was associated with lower baseline depressive symptoms (β = −0.27, p < 0.001). Parent-child connectedness (youth-report) was indirectly predictive of baseline depressive symptoms through locus of control (β = −0.06, p < 0.05). Family economic stress was predictive of less growth in depressive symptoms over time (β = −0.20, p < 0.05). General family stressors, neighborhood safety, and parent report of parent-child connectedness were not predictive of adolescent depressive symptoms. In a sensitivity analysis using an autoregressive model, adolescent-report of parent-child connectedness was the most consistently predictive measure of adolescent depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Overall, the results suggest that feelings of family connectedness and control are more important to understanding baseline depressive symptoms than physical, contextual factors. However, some adversity may be healthy and provide adolescents with experiences that slow the growth of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Auerback, R. (2015). Depression in adolescents: causes, correlates and consequences. Psychological Science Agenda. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2015/11/depression-adolescents.

Berndt, D. J., Kaiser, C. F., & Van Aalst, F. (1982). Depression and self‐actualization in gifted adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 142–150.

Blau, G. J. (1984). Brief note comparing the Rotter and Levenson measures of locus of control. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 58, 173–174.

Butler, A. M., Kowalkowski, M., Jones, H. A., & Raphael, J. L. (2012). The relationship of reported neighborhood conditions with child mental health. Academic Pediatrics, 12, 523–531.

Carr, D., & Springer, K. W. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 743–761.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). National survey of children’s health (OMB Control No. 0920–0406). Atlanta, GA: Author.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255.

Constantine, M. G. (2006). Perceived family conflict, parental attachment, and depression in African American female adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12, 697–709.

Corcoran, J., & Franklin, C. (2002). Multi-systemic risk factors predicting depression, self-esteem, and stress in low SES and culturally diverse adolescents. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 5, 61–76.

Crandall, A., Magnusson, B. M., Novilla, M. L. B., Novilla, L. K. B., & Dyer, W. J. (2017). Family financial stress and adolescent sexual risk-taking: the role of self-regulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 45–62.

Culpin, I., Stapinski, L., Miles, Ö. B., Araya, R., & Joinson, C. (2015). Exposure to socioeconomic adversity in early life and risk of depression at 18 years: the mediating role of locus of control. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 269–278.

Decker, P. J., & Cangemi, J. P. (2018). Emotionally intelligent leaders and self-actualizing behaviors: any relationship? IFE PsychologIA: an International Journal, 26, 27–30.

Duncan, T. E., Duncan, S. C., & Strycker, L. A. (2006). An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: concepts, issues, and application. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Dupéré, V., Leventhal, T., & Vitaro, F. (2012). Neighborhood processes, self-efficacy, and adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 183–198.

Ellis, R. E., Seal, M. L., Simmons, J. G., Whittle, S., Schwartz, O. S., Byrne, M. L., & Allen, N. B. (2017). Longitudinal trajectories of depression symptoms in adolescence: psychosocial risk factors and outcomes. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48, 554–571.

Ford, J. L., & Rechel, M. (2012). Parental perceptions of the neighborhood context and adolescent depression. Public Health Nursing, 29, 390–402.

Furnham, A., & Steele, H. (1993). Measuring locus of control: A critique of general, children’s health- and work-related locus of control questionnaires. British Journal of Psychology, 84, 443–479.

Gordon, M. S., Tonge, B., & Melvin, G. A. (2012). The self-efficacy questionnaire for depressed adolescents: a measure to predict the course of depression in depressed youth. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46, 47–54.

Guerra, C., Farkas, C., & Moncada, L. (2018). Depression, anxiety and PTSD in sexually abused adolescents: association with self-efficacy, coping and family support. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 310–320.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627.

Kouros, C. D., & Garber, J. (2014). Trajectories of individual depressive symptoms in adolescents: gender and family relationships as predictors. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2633.

Lambert, M., Fleming, T., Ameratunga, S., Robinson, E., Crengle, S., Sheridan, J., & Merry, S. (2014). Looking on the bright side: an assessment of factors associated with adolescents’ happiness. Advances in Mental Health, 12, 101–109.

Lee, R. M., Draper, M., & Lee, S. (2001). Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: testing a mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48, 310–318.

Lee, T. K., Wickrama, K. A. S., & Simons, L. G. (2013). Chronic family economic hardship, family processes and progression of mental and physical health symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 821–836.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford press.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). The instinctoid nature of basic needs. Journal of Personality, 22, 326–347.

Maslow, A. H., Frager, R., Fadiman, J., McReynolds, C., & Cox, R. (1970). Motivation and personality (Vol. 2). https://doi.org/10.1037/h0038815.

McLaughlin, K. A., Costello, E. J., Leblanc, W., Sampson, N. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2012). Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1742–1750.

Mezulis, A., Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., Priess-Groben, H. A., & Simonson, J. L. (2014). Affective, biological, and cognitive predictors of depressive symptom trajectories in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42, 539–550.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide (8th Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Major depression: Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml.

O’Donnell, J., & Saker, A. (2018, March 19). Teen suicide is soaring. Do spotty mental health and addiction treatment share blame? USA Today. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2018/03/19/teen-suicide-soaring-do-spotty-mental-health-and-addiction-treatment-share-blame/428148002/.

Oldfield, J., Stevenson, A., Ortiz, E., & Haley, B. (2018). Promoting or suppressing resilience to mental health outcomes in at risk young people: the role of parental and peer attachment and school connectedness. Journal of Adolescence, 64, 13–22.

Olsson, G., & Von Knotting, A. L. (1997). Depression among Swedish adolescents measured by the self rating scale Center for Epidemiology Studies-Depression Child (CES-DC). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 6, 81–87.

Powell, J. W., Denton, R., & Mattsson, Å. (1995). Adolescent depression: Effects of mutuality in the mother-adolescent dyad and locus of control. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 263.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57, 316–331.

Saluja, G., Iachan, R., Scheidt, P. C., Overpeck, M. D., Sun, W., & Giedd, J. N. (2004). Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 158, 760–765.

Scott, S., Wallander, J., Cameron, L., Scott, S. M., & Wallander, J. L. (2015). Protective mechanisms for depression among racial/ethnic minority youth: empirical findings, issues, and recommendations. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 18, 346–369.

Starnes, D. M., & Zinser, O. (1983). The effect of problem difficulty, locus of control, and sex on task persistence. The Journal of general psychology, 108, 249–255.

StataCorporation. (2015). Stata statistical software. Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Sullivan, S. A., Thompson, A., Kounali, D., Lewis, G., & Zammit, S. (2017). The longitudinal association between external locus of control, social cognition and adolescent psychopathology. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52, 643–655.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D. A., Liu, H., & Needham, B. (2005). Stress in childhood and adulthood: effects on marital quality over time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1332–1347.

Utter, J., Denny, S., Peiris-John, R., Moselen, E., Dyson, B., & Clark, T. (2017). Family meals and adolescent emotional well-being: findings from a national study. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 49, 67–72.e61.

Utter, J., Denny, S., Robinson, E., Fleming, T., Ameratunga, S., & Grant, S. (2013). Family meals and the well‐being of adolescents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 49, 906–911.

Wadsworth, M. E., Rindlaub, L., Hurwich-Reiss, E., Rienks, S., Bianco, H., & Markman, H. J. (2013). A longitudinal examination of the adaptation to poverty-related stress model: predicting child and adolescent adjustment over time. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42, 713–725.

Weissman, M. M., Orvaschel, H., & Padian, N. (1980). Children’s symptom and social functioning self-report scales: Comparison of mothers’ and children’s reports. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders, 168, 736–740.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2013). Resiliency theory: a strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Author Contributions

AC conceived of the study and the analytical design, performed statistical analyses and interpretation, drafted the methods and results sections, and edited the manuscript. EAP and GCB wrote sections of the introduction and discussion. BMM drafted sections of the introduction and helped edit the entire manuscript. CLG, MDB, and MLBN reviewed and edited the manuscript. RAB was a principal investigator for the Flourishing Families Project and helped edit the manuscript. All authors helped with the interpretation of results and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crandall, A., Powell, E.A., Bradford, G.C. et al. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a Framework for Understanding Adolescent Depressive Symptoms Over Time. J Child Fam Stud 29, 273–281 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01577-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01577-4