Abstract

Do new digital consumption channels of music depress sales in old physical ones, or are they complementary? To answer this question, we exploit product-level variation in sales and prices of over 4 million products, observed weekly between 2014 and 2017 for the entire French market. A unique feature of our data is that we observe sales for both physical and digital products, as well as streaming consumption. At the track-level, we find that streaming displaces digital sales. At the more aggregate artist-level, digital sales displace physical sales, but streaming implies a promotional effect on physical sales. This complementarity is driven by popular genres, i.e., Pop and Variety. Most of our findings are robust to whether we consider the hits or include the products that belong to the long tail. Our findings bridge two streams of literature as we show that displacement between consumption channels at the product level can coexist with complementarity at a more aggregate level.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

After more than a decade of falling revenue, the music industry is returning to growth. Since 2015, its global revenues are increasing again, and, since 2017, the biggest part of its revenues originate from streaming services, which timidly started in 2005.Footnote 1 This industry has gone through significant transformations since the early 2000s. Digitization drastically accelerated these transformations, by simultaneously affecting the nature of products, their distribution, and the way they are consumed. These transformations are shared by many media industries (films and video games) and attract strong and sustained attention from researchers in various fields. In economics, the main questions revolve around prices, revenue sharing, and in particular competition between consumption channels. Even though there is now a flourishing literature aiming to shed light on substitution between specific channels, this paper aims to study all relevant channels (i.e., physical, digital and streaming) in a well-founded and unified way.

It is a contribution to economic policy as it touches upon questions related to the aggregate demand and producers’ revenue, the market structure, and the revenue sharing of this industry. Indeed, the replacement of some products by other products—and some distribution channels by others—can yield significant changes in the aggregate demand and producers’ revenue.Footnote 2 In terms of market structure, both the distributors of music and the artists are affected by these changes. While the majors and the large retailers were the heart of the recorded music industry before the digitization, now a few dominant platforms like Youtube, Spotify and Apple are occupying the economic space and concentrate a large part of the revenue generated.Footnote 3 When considering the artists, digitization is often described as having favored the “stars,” even though it enables a large number of “niche” artists to have a chance to share their works to a large audience. In terms of revenue sharing, digitization has increased the number of artists who are tied to a record company (especially a major) with a license contract, in which the producer (i.e., the record company) is in charge of the recording but not the promotion of the music. This is opposed to a more traditional form of contract, in which the record company takes in charge of the promotion of the music that it produces (See BearingPoint, 2017). More and more artists use streaming platforms as the principal promotion channels of their work nowadays. It remains unclear, however, whether this change in the promotion method of music benefits the artists or not. Highlighting how digitization impacts the popularity of artists (as measured by the consumption of their music) across the various channels should help to shed light on this question. Also, emphasizing the role of the heterogeneity across genres is key to understand how the variety of consumption of cultural products is affected by digitization. Finally, evaluating whether there is a displacement or an enhancement effect between consumption channels is of importance to predict which distributors of recorded music will see their power and influence reinforced by the digitization, and which will see them decline, with a potential impact on the current and future market structure.

To address these issues, we use a rich dataset that covers virtually the whole French market for recorded music between 2014 and 2017. A unique feature of our data is that we observe sales and prices for both physical and digital products, as well as streaming consumption. These data enable us to ask whether there is displacement or complementarity between old and new ways of listening to recorded music—what we name consumption channels hereafter. The old consumption channels correspond to physical sales (CDs and Vinyls), while the new ones to digital sales (downloads) or streaming.

We exploit variation in tracks and albums prices to estimate the impact of streaming on the digital sales channel, and the impact of each of the two new consumption channels (download and streaming) on the old physical sales one. At the product level, i.e., for tracks, we show that there exists a substitution effect between the new and old channels, which has already been documented by other researchers. At the artist-level, we find a substitution effect between digital downloads and physical sales. At the same time, however, there is a complementarity effect between streaming and physical sales that is mostly driven by the genres Pop and Variety. This suggests that artists who are positioned in specific “segments” benefited from the introduction of the streaming channel (at least in terms of units consumed). That finding complements some recent evidence in the literature. Finally, at the market-level, our results remain inconclusive. Our findings bridge two streams of literature as we show that displacement between consumption channels at the product level can coexist with enhancement at a more aggregate level. Following other articles from the literature, we use the terms “substitution” and “displacement” as well as “complementarity,” “promotion” and “enhancement” interchangeably in the paper. From a policy perspective, this indicates that distributors on the physical channel can remain a counterbalance against increasingly powerful streaming platforms.

Our paper relates to the literature studying the impact of digitization. On the supply side, prior work suggests that digitization led to increased quality (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2016; 2018a; Waldfogel, 2012) and an increased variety of offered content (Aguiar & Waldfogel, 2018a; Luca & McFadden, 2016). On the demand side, some papers highlight how the digitization of content and new consumption channels led to an increase in the quantity consumed (Aguiar, 2017; Datta et al., 2018), although some other papers argue that the market is not expanding. Some empirical evidence suggests there has been an increase in consumed variety (Datta et al., 2018; Luca & McFadden, 2016), while another work is ambiguous on this point (Kretschmer & Peukert, 2020).

Our paper contributes more specifically to the growing body of literature that focuses on the substitution between music consumption channels: substitution between traditional and new channels (e.g., physical and digital sales) or substitution between digital channels (e.g., per-purchase vs. on-demand). First, several papers document the impact of piracy and unlicensed content in the recorded music market. A large literature documents a significant displacement effect of unlicensed content (e.g., Aguiar and Martens (2016; Liebowitz, 2016); Aguiar and Waldfogel (2016) do not find evidence of such displacement in their study relying on clickstream data. They even find a small complementarity between unlicensed and licensed downloads, in some countries. Finally, Aguiar (2017) shows how piracy can be stimulated by free streaming using individual-level data from France. His results suggest that streaming increases product discovery and music consumption (including consumption of unlicensed content).

Second, a more recent strand of literature analyzes the impact of streaming services on non-digital sales. Wlömert and Papies (2016) highlight the existence of cannibalization between streaming (free and paid services) and revenue from hard copies. Hiller (2016) finds a strong substitution effect of YouTube on physical sales (with YouTube views replacing about a quarter of album sales). In contrast, Kretschmer and Peukert (2020) find that YouTube has generated positive externalities on physical sales (with 20 percent extra revenues from songs available on the platform).Footnote 4 Results from Aguiar (2017) also go in that direction as he finds that free streaming also stimulates the consumption of licensed content, i.e., digital sales.

Our work relates most closely to the analysis of streaming by Aguiar and Waldfogel (2018b). They estimate displacement based on weekly data on digital track sales and streams in over 21 countries, between April and December 2013. However, their streaming data covers the top 50 only. They also exploit aggregate sales of tracks and albums, both in digital and physical format, for the period 2012–2013 for the USA which is prior to the true boom of streaming consumption. In France, this boom took place in 2015, which is covered by our own data set.

In sum, this overview indicates that there is a large but somewhat fragmented literature studying the question of displacement in the music industry. The conclusions from this literature are sometimes contradictory, which may in part be due to the consideration of different time periods or different adopted methodologies. Thanks to our data, we can analyze the market, encompassing physical and digital sales, as well as streaming, which has been rarely possible in the literature. Furthermore, our analysis does not need to focus only on the hits; we can also include the products belonging to the long tail. Finally, we can also comment on the heterogeneity of the effect across genres.

In terms of empirical strategies, prior works can be classified into three categories: (i) papers based on individual data from music consumers, (ii) papers exploiting exogenous shocks, and (iii) papers using data aggregated at the product and artist levels. First, a strand of literature exploits the availability of individual-level data. Waldfogel (2010) uses survey data to assess consumers’ willingness to pay for illegal and legal products and finds that the rate of the sales displacement ranges between \(-\) 0.15 and 0.3 which means that an additional stolen song reduces purchase between a third and a sixth of a song. Wlömert et Papies (2016) use a quasi-experimental design and periodic survey for a large population of music consumers, enabling them to incorporate individual fixed effects in their empirical analysis. Aguiar and Martens (2016); Aguiar and Waldfogel (2016) exploit individual clickstream data and estimate a panel OLS model with individual and country fixed effects.

Second, several papers have used aggregate sales data and exploit exogenous shocks to estimate difference-in-differences models. To assess the substitution between illegal and legal consumptions, Hong (2013) uses the introduction of Napster in 1999 that was a pioneering peer-to-peer file sharing internet software that remained dominant until being shut down in 2001 after running into legal difficulties over copyright infringement. In the same spirit, but to assess the substitution between streaming consumption and sales (physical and digital combined), Hiller (2016) uses a natural shock that occurred in 2009 during which all the content produced by the company Warner was suddenly withdrawn from Youtube for a period of nine months. Kretschmer and Peukert (2020) use a similar shock the (“GEMA shock”) in 2009. That year, a legal dispute occurred between the royalty collection society that represents artists in Germany and Youtube. It resulted in almost all music videos being unavailable in this country for several months.

Finally, some papers have relied on aggregated sales data at the product and artist levels. In particular, Aguiar and Waldfogel (2018b) have data at the song and artist level for multiple countries. This enables them to estimate the impact of streaming on other music channels using song, artists and country-fixed effects, therefore accounting for common shocks in the popularity of songs across countries. Our paper belongs to this third category. We also have detailed data at the song or album level, which allows us to include product-fixed effects. However, in contrast to Aguiar and Waldfogel (2018b), we only observe data for a single country, France, so we cannot exploit variation across countries. We, therefore, suggest an alternative empirical strategy that relies on variation in prices to identify the impact of new music channels on existing ones.

Even though the question of substitutability and complementarity in the media industries has attracted important attention from researchers over the last decade, this paper reconciles two strands of empirical evidence in highlighting how they can co-exist—with substitution at the product level, but complementarity at the artist level. It also provides an analysis of the effects in the long tail and across genres, which to our knowledge has not received much attention before.Footnote 5

Compared to the existing work, our contribution is substantive in two ways. First, we use a unique dataset that covers the entire market, with product-level sales and streams. This includes observations for the less popular products which are virtually never observed in other studies. Second, we do not limit attention to physical goods versus digital goods, or digital goods versus streams. Our analysis encompasses all the existing consumption channels in a unified framework which allows to provide more robust grounds for the economic policy questions previously mentioned. From a methodological perspective, we suggest an empirical approach that relies on the variation of prices. This makes the approach applicable in circumstances where quasi-experiments are not available. Our analysis confirms previous empirical findings and, in addition, provides valuable insights on the coexistence of substitutability and complementarity in this market, highlighting the presence of heterogeneity across artists and genres.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the data used in the estimation. Section 3 introduces the econometric framework. Section 4 presents the estimation results. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes.

2 The recorded music industry

2.1 Background

Recorded music products are typically sold in three forms: (i) as physical goods (CD and vinyl) sold by brick-and-mortar or online retailers; (ii) as digital goods, i.e., downloaded music from platforms and websites; (iii) as streams, sold as large bundles of songs through subscription. The market for physical products is relatively fragmented, with many retailers varying widely in terms of size. For example, supermarkets, specialized independent shops, and marketplaces such as eBay and Amazon all serve the physical market. The market for digital products (i.e., downloads) is much more concentrated with only a few platforms serving consumers, such as iTunes, Amazon Music, and Soundcloud.Footnote 6 The streaming market is even more concentrated: a limited number of companies offer either audio services (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music, Amazon Music), video services (Youtube), or radio services (Pandora and Napster). Also, it is much more common to see price variation for physical products across retailers and over time. For digital products, we often observe focal prices, such as 1.29€ for a track and 9.99€ for an album in France. Subscription prices for streaming services are also homogeneous over time and across platforms, with a focal price of 9.99€ per month in France.Footnote 7

Digitization in this industry did not only come hand-in-hand with the emergence of streaming platforms: it also opened an illegal consumption channel with the possibility for a large number of people to exchange and consume unlicensed content, i.e., piracy, via Peer to Peer (P2P) networks for example. While a large body of literature focuses on the impact of piracy on sales and documents the existence of substitution between illegal content consumption and sales (Liebowitz, 2016; Savelkoul, 2020), a more recent strand of the literature discusses the impact of streaming on piracy. For example, Aguiar (2017) finds that free streaming can positively influence piracy at the individual level. Aguiar and Waldfogel (2018b) find that free and premium streaming combined displaces piracy at the aggregate level. Various industry reports and press articles also suggest that streaming consumption substitutes piracy.Footnote 8 Thus, streaming might indirectly stimulate sales through its effect on piracy. Unfortunately, it is hard to measure it and therefore our study focuses on legal channels for which good and fine-grained data exist.Footnote 9

Figure 1 shows the evolution of global recorded music revenues per consumption channel. Physical sales (excluding performance rights and synchronizationFootnote 10) represented virtually 100 percent of the industry revenues in 2001 and dropped to less than a quarter of revenues in 2020. Digital sales began around 2004 and gradually grew to up to 35 percent of industry revenues in 2013; since then, the share of digital sales has continuously decreased to about 6 percent in 2020. Streaming timidly started in 2005 to reach a share of 8 percent in 2012; it truly took off in 2016 with a market share of 35 percent and its share subsequently increased by at least 10 percentage points per year, to reach 71 percent of the market in 2020.

More specifically in France, the share of digital sales (downloads and streaming) grew from roughly 30 percent in 2014, to reach almost 50 percent in 2017, based on data published by the SNEP (see Fig. 2, in Appendix A). Therefore, the time period of our study covers the “switch” from a market where the main part of revenue originated from physical sales to a market where digital revenue is predominant. The most recent figures from the SNEP indicate that the share of digital sales almost reached 72 percent in 2020.

2.2 Data

Our main source of data originates from the market research firm GfK. It contains weekly product level information for the entire French market on physical and digital sales of recorded music, as well as the number of streams generated on audio, video, and radio platforms. The data cover virtually the entire digital music market (about 99 percent for the digital sales and all streaming according to informal discussions with GfK) and also almost completely the physical market (about 95 percent). In addition to sales, the data also include product characteristics such as names of artists, publishers, labels, main genre, subgenre, and release year.

Physical sales products refer to physical albums and singles, as sold in supermarkets, specialized shops, and online websites. Digital sales are downloads of albums or tracks (i.e., individual songs) that took place on legal platforms such as iTunes and Qobuz. Streams are always at the track-level and originate from audio platforms such as Spotify, Deezer, or Qobuz, and video platforms such as Youtube and Dailymotion.Footnote 11 Typically, consumers have the option to purchase non-durable music products, i.e., streams (as highlighted in Donnat (2018), and described in Walter and Hiller (2019) or purchase a durable good, which can be physical or digital.Footnote 12

For physical and digital sales, we observe both quantities and revenues, and hence the average price per track or album. Streaming refers to the quantity consumed (at zero price), both from users with a subscription plan and from users with free access interrupted by ads. Even though we observe quantities for each type of streaming (premium audio, free audio, and free video streaming), we pool them together as quantities observed are highly correlated with each other.Footnote 13

For physical and digital sales, the original data set covers the period 2006–2018. The streaming data starts during the last week of 2014 and ends in 2018. However, GfK does not collect the video streaming numbers since January 2018, so we restrict our analysis to the period 2014–2017. The original data consist of a large number of weekly cross-sections, which we combine based on the artist and title names. We remove 56 of the 208 weeks for which the data provided by Gfk was incomplete (because data for a given channel are missing, the basket item appears several times, etc.), leaving a final sample of 152 weeks.

For the physical sales, GfK explicitly codes whether a product is an album or a single. For the digital sales, this information is only partly coded. When missing, we define a product as a track if the price is at most 3€ and as an album if the price is above 4.9€.Footnote 14 We remove the products priced in between, which represent a negligible number of observations (less than 0.5 percent).Footnote 15 Regarding streams, this always refers to tracks in our dataset. We remove a small number of price outliers: products with a price lower than 0.9€ or greater than 60€ on the physical channel (which removes very high-end special editions); and products with a price greater than 30€ for the digital albums and greater than 5€ for digital tracks (where this was coded by GfK). These cut-offs are arbitrary but do not affect the results as they remove only a very small number of observations, i.e., 36,251 observations, what represents 0.12 percent of observations. Finally, we remove observations with an outlier price variation (beyond +100 percent of the price of a given product).

The creation of the panel data set highlights that some products are not sold or consumed every month since the launch date. GfK confirmed to us that it registers virtually every physical and digital sale. Hence, the absence of sales of a product in a given week indicates a true zero value for the week at which we observe the first sale. For such products with zero sales in some weeks, we do not observe the average price, so we use a simple linear interpolation to impute the missing price information.Footnote 16 Regarding streaming, the interpretation of a missing quantity takes another meaning. Indeed, to appear in GfK’s panel, a title must be streamed at least 100 times on audio-streaming platforms and at least 1000 times on video-streaming platforms on a given week. All the consumptions below this threshold enter a basket which is provided by GfK. Even though this basket allows us to compute the total number of units consumed on the market, the data are partially censored at the track-level.Footnote 17 To deal with that issue, we use a linear interpolation for tracks with missing values and for which we can reasonably assume that the track was available on the market during the week in question and that the observation was possibly censored by the 100/1000 streams threshold rule adopted by GfK. We interpolate at the track-level.Footnote 18

Finally, we complement this data with an extensive dataset published by the National Agency of Radio Frequencies (ANFR) that contains information on the number of 2G, 3G, and 4G antennas on the French territory between 1997 and 2019.Footnote 19 We use this data to compute the weekly number of active 4G antennas between 2014 and 2017 and use it as an instrument in the market-level analysis.

2.3 Descriptive statistics

2.3.1 Number of observations

As shown in Table 1, the final dataset is a panel of 29,672,540 observations, covering 4,330,868 unique products from 894,134 unique artists observed during 152 weeks. Albums make up to 25 percent of all products and relate to either physical or digital sales (i.e., not streaming). Tracks make up the remaining 75 percent of the products. They mainly refer to digital sales and streaming. For physical sales, there are also singles, i.e., two tracks on CDs or Vinyls, but these make up a very small number of the observations during our sample, so we exclude them from our analysis.

2.3.2 Volumes and market shares by consumption channel

Since our dataset covers virtually the entire French market between 2014 and 2017, we can provide a comprehensive description of changes in the market shares of each channel: physical sales, digital sales, and streams. Because we do not have an unambiguous measure for the average price per stream, we focus on market shares in volume rather than in value terms. To aggregate sales over tracks and albums, we express album sales in track-equivalent units, assuming there are ten tracks per album, which is a common assumption in the literature (see for instance Aguiar & Waldfogel, 2018b). Figure 3 in Appendix A shows the evolution of market shares over time.

Table 2 provides information on the absolute numbers behind these market shares. The total volume of digital sales is on average 827,196 track-equivalent units per week. This is indeed considerably lower than the total volume of physical sales of on average 3.9 million per week, and the total volume of streams of on average 535 million units per week. Compared to the global figures presented earlier, the French market appears to be roughly similar, except with respect to the number of digital sales that represent a small share of volumes every week.

This overview seems to suggest that the economically most relevant phenomenon to study is the impact of streaming on physical sales. However, digital sales still generate some significant industry revenue compared to streaming, so studying the impact of streaming on digital sales is also of economic interest (See Fig. 1). Note that it is not possible to directly assess the impact of streaming on physical sales at the track level (because physical sales for tracks are virtually non-existent). We, therefore, conduct this part of the analysis at the artist level.

2.3.3 Sales volumes

Table 3 presents summary statistics of our main variables. The top panel shows the summary statistics for sales volumes, broken down by channel (physical, digital, and streaming) and format (track and album). These figures confirm that digital sales volume is on average very small, including many zero values. Streaming volumes are much higher than sales, on average.

Figure 4 shows the change over time in the number of sales on the three channels. The total volume of physical sales stays relatively stable, except for the traditional end-of-the-year shocks around Christmas. Total digital sales volume is steadily declining to reach, in 2017, half of what it was at the end of 2014. The total number of streams, as presented in the lower right corner of the figure, is on the rise, starting from about 600 million in 2014 to reach about 1.4 billion in 2017. The shock in the middle of 2016 is due to a change in GfK’s data construction method. However, it only impacts very marginally the volume of streams used in our data (presented in the lower-left corner of the figure). To account for this event, we include week-year fixed effects in the regressions hereafter. We also conducted robustness analyses which suggest that it does not affect our results qualitatively or quantitatively.

The top panel of Table 3 presents statistics on the volumes. On average, a physical album is sold about 9 times a week, while a digital album is sold twice a week. Songs available on the streaming platforms are streamed about 11 thousand times a week, on average.

2.3.4 Price and price variation

The bottom panel of Table 3 shows the summary statistics for prices, which are key factors of sales volumes. The price of a digital track is on average 1.3€, with a standard deviation of 0.2€. The price of a digital album is on average 10€, with a standard deviation of 2.1€. Finally, the price of a physical album is on average 13.5€, with a standard deviation of 7€. The histograms shown in Fig. 5 provide additional insights into the price variation. The prices of digital tracks and albums appear as “standard” and do not vary much over products, or time. Indeed, the vast majority of digital tracks and albums are sold at respectively 1.29€ and 9.99€. Nevertheless, there is residual variation around these price values, especially for albums. The prices of physical products show considerably more variation. While there are focal prices for physical albums at 6.99€, 10€ and 14€, as indicated by the spikes, there remains a considerable variation around these focal values.

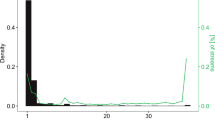

We now provide some further detail on general and within-product price variation, since this is relevant to our empirical approach. Figure 7 shows the distribution of the percentage change in prices within a given product. This shows that prices often stay relatively stable, but also that there exists variation for both digital and physical products. This price variation tends to be infrequent and discrete (lumpy) and is also common across different “Top” categories and genres. This will motivate our empirical approach outlined in the next section. Table 8 provides further details on the frequency and magnitude of these price changes. On the digital channel, a price change is observed for 20 percent of the product-week observations. On average, this price change is 0.4 percent, which indicates an upward trend. On the physical channel, price changes occur in 95 percent of cases, with an average magnitude of \(-\) 0.85 percent, which is the sign of a downward trend. At the product level, we observe similar phenomena, with much more variation observed on the physical channel, more significant price changes, and a downward price trend. On average, at the digital product level, we observe a price change for 5 percent of time periods. This means that over 152 weeks of observation, we would observe 8 weeks during which a change in price took place, with a price being stable for the remaining weeks. At the physical-product level, these price changes are more frequent. Indeed, on average, at the product-level, we observe a price change for about half of the periods of observation.

In sum, although we observe important price variation across products and over time, there is also meaningful within-product price variation.

2.3.5 Tops and genres

Figure 8 and Table 9 highlight the significant concentration of sales and streams over a few top tracks and albums. This concentration of consumption on a few very popular products (the Hits) and the existence of a long tail of products with a limited number of sales is typical of various entertainment industries in the Digital Age as discussed in Anderson (2006). The availability of sales information for the products falling in this long tail is rare, what could moderate the conclusions from the prior literature which very often focuses on the most popular products. We will therefore exploit this information to see how our results vary whether we consider the top 50, 200, 1000, 5000, or all products, at each level of data aggregation (product level and artist-level). Table 10 shows how genres vary across formats (albums or tracks), and Table 11 across consumption channels.

As shown in Table 10, about 27 percent of available products belong to the genre ‘Pop’. Five additional genres represent between 3 and 7 percent of available products: Rock, Urban Music, Variety, Electro/Dance, and Classical Music. For each level of data aggregation (product-level and artist-level), we will carry out an analysis for each of these genres to comment on their heterogeneity.

3 Empirical framework

Based on our product-level data by week, we aim to identify the extent to which different music channels imply sales displacement because of substitution, or rather sales enhancement from complementarities (e.g., from the possibility to discover new music, known as the sampling effect (see for example Peitz & Waelbroeck, 2006). More specifically, we are primarily interested in measuring the impact of streaming on the older channels, i.e., (i) the impact of the streaming channel on the digital channel, and (ii) the impact of the digital and streaming channels on the physical channel. In practical terms, we consider that the two main music formats, i.e., tracks and albums, have a different presence in the three channels, as documented in Sect. 2. Tracks are only available in the digital and streaming channels, whereas albums are available only in the physical and digital channels.

We incorporate this feature of the music market in several ways. First, we consider a product-level analysis at the track-level. Here, we focus exclusively on the impact of streaming on digital sales. Hence, our product-level analysis does not study the impact of the digital sales and streaming channels on physical sales. This would not be possible for physical tracks (singles), because these are virtually non-existent in our dataset. Moreover, it cannot be done for physical albums, because we do not observe streams for albums (as GfK counts streams from full albums as individual track consumptions).Footnote 20 Second, we implement our analysis at the more aggregate artist-level, by considering track-equivalent units for album sales (based on our conversion of one album into ten tracks). Our artist-level approach enables us to measure the impact of both the digital and streaming channels on the physical channel in an integrated way. Finally, we repeat this analysis at the level of the entire French market.

A typical approach to measure the impact of a new music channel on an existing one consists of regressing sales of the existing channel on the sales of the new channel. This entails a typical endogeneity issue: sales of a track (or album or artist) are generally subject to the same common shocks (an unexpected change in popularity for instance), so that any positive relationship between the sales on the existing and new channels may simply capture this common shock rather than a complementarity effect between both sales channels. To address this issue, several papers exploited natural field experiments, such as the temporary withdrawal of part of the content from streaming platforms (Hiller, 2016; Hong, 2013; Kretschmer & Peukert, 2020). Other papers used panel data from different countries and include fixed effects per track and time period to control for the current common international popularity of a track or artist (e.g., Aguiar & Waldfogel, 2018b), Aguiar and Martens (2016). However, these approaches are not always feasible in terms of data requirements as in our case, since our data do not cover a comparable temporary shut-down or a change in the regulation, and are available only for France. Furthermore, previous work is still based on certain assumptions (e.g., the assumption that the withdrawal of part of a channel is not correlated with its popularity in the first approach, and the assumption that local sales shocks are not correlated across countries, conditional on the included track-period fixed effects). Here, thanks to the fact that we observe the price of each product every week, we can implement an instrumental variable approach to identify the impact of newer music channels on existing ones.

More formally, let \(q_{it}^c\) denote the quantity of product i sold or streamed on channel c at time t. A product i refers to an individual track or to a more aggregate artist (where quantities are then the total of track-equivalent units across tracks and albums of the same artist). The channel c is either the physical, digital or streaming channel. In the spirit of other works such as Aguiar and Waldfogel (2018b) and Kretschmer and Peukert (2020), we consider linear regression models for sales in the older channel on sales in the newer channel(s). In our first model, we regress digital sales on streams, at the track-level, that is:

where \(\mu _i\) is a time-invariant fixed effect for product i, \(\theta _t\) is a week-year fixed effect, and \(\varepsilon _{it}^{\text {dig. tracks}}\) is the error term. Our main interest is in the coefficient \(\alpha _1\). If \(\alpha _{1}<0\), this means that the streaming channel displaces the digital channel. If instead \(\alpha _{1}>0\), the streaming channel enhances the digital channel.

Our second model considers aggregate artist sales. Here we study how the track-equivalent total quantity sold by an artist on the physical channel is affected by track-equivalent sales observed in the digital channel and by the number of streams:

The subscripts i now refer to the artist. This model allows us to estimate the impact of two newer channels on physical (track-equivalent) sales through the coefficients \(\alpha _1\) and \(\alpha _2\).

Finally, a third model considers aggregate sales at the market level. Here we study how the track-equivalent total quantity sold on the physical channel in a given week is affected by the sales and streams on newer channels. We regress physical sales on the total track-equivalent sales observed on the digital channel and the total number of streams. The model is then:

This model also allows us to estimate the impact of two newer channels on physical (track-equivalent) sales. However, the level of aggregation does not allow to include product or artist fixed effects, only time fixed effects.

To estimate these models, the simplest approach would ignore both the product and time fixed effects (so \(\mu _i = \theta _t =0\)) and use the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator. This would, however, involve an endogeneity problem because demand shocks for the product on the older channel (\(\varepsilon _{it}^c\)) are likely strongly correlated with the included demand variables for the same product on the newer channel(s), e.g., \(q_{it}^{\text {streams}}\) in Eq. (1). Including the product and time fixed effects may mitigate this concern, but it is likely that there is a strong remaining conditional correlation, e.g., a positive coverage of a particular song in French media may induce both more streaming and higher digital sales.Footnote 21 With panel data on multiple countries, a full set of multiplicative product-time fixed effects (\(\mu _{it}\)) could be included, as done by Aguiar and Waldfogel (2018b), although it would not capture possible within-country sources of correlation.

To cope with the endogeneity issue of the included demand variables, we adopt an instrumental variable approach. Good instruments would be product- and time-varying variables that have explanatory power for included demand variables, but do not directly enter the sales displacement/enhancement regression. Natural candidates are the product prices at the various sales channels (or the determinants of these prices).Footnote 22

To see this, we show, in Appendix B, how the track-level regression model presented in Eq. (1) can be derived from the following system of linear demand functions for channel \(c=\{\text {dig. tracks, streams}\}\):

where \(p_{it}^{\text {dig. tracks}}\) denotes the price of product i at time t on the digital channel, and the usage price for streaming \(p_{it}^{\text {streams}}\) does not enter as it is zero.Footnote 23 In Appendix B, we also derive these demand functions from a standard consumer utility maximization problem, and show how it results in the displacement/enhancement regression (1). We finally extend this approach to the artist-level regression (2) model with three channels and two non-zero prices, \(p_{it}^{\text {phy. tr. equ.}}\) and \(p_{it}^{\text {dig. tr. equ.}}\). Under the assumption that the prices are uncorrelated with the demand errors \(\xi _{it}^c\), the demand equations can be estimated consistently. As such, they serve as the first-stage regressions to estimate Eqs. (1) and (2) using two-stage least squares

In principle, one could modify this approach and use price instruments instead of prices themselves, as in Berry (1994) and Berry et al. (1995).Footnote 24 However, in our setup, considering that prices are uncorrelated with the demand error does not appear to be unreasonable. In many other industries which mainly entail variable costs, the correlation between the prices and demand shocks is conveyed through the costs. Indeed, by definition, variable costs can be impacted by unexpected changes in the level of production because of demand shocks; since prices are driven by costs, these shocks affect the present prices. In the music industry, however, costs are mainly fixed (i.e., there is almost no cost variation) and so are not impinged by demand shocks.

Prices can therefore not be correlated with demand shocks through the cost channel. Prices in the music industry are not the result of a standard supply and demand model. They are set to fuel network effects and/or are the result of the objective of firms (artists, music labels, platforms) to achieve some (large) share of the market, i.e., they are not the result of short-run profit maximization. Empirically, this translates into the price patterns documented in Sect. 3.

Prices are focal around a limited number of values—as is generally the case for digital goods. Remaining within-product price variation tends to be infrequent and discrete across all top categories and genres, as discussed in Sect. 3, and is clearly not driven by sudden unobserved product-level demand shocks.

Hence, we consider that prices are good instruments in our case. Note finally that we include a rich set of product and time fixed effects (i.e., at the week-year level). This is in line with other papers that directly estimates displacement/enhancement regressions, and also helps to filter out any remaining time-invariant product shocks and market-level shocks.

4 Estimation results

As discussed in the previous section, we are interested in estimating the impact of the newer music channels on the older ones by means of the commonly used regression model presented in Eq. (1). As a benchmark, we first consider the results from OLS and fixed effects estimations. However, we focus the empirical analysis on the 2SLS estimations, where prices are used as instruments for the included quantity variables.

In the first subsection, we present the results from estimating Eq. (1) at the most disaggregate level, i.e., where product i refers to tracks. Because tracks are available only on the digital and streaming channels, this level of disaggregation does not allow us to consider the impact of both digital and streaming on the physical channel. We, therefore, address it in the second subsection at a more aggregate level of analysis, the artist level, where we sum over tracks and albums by using track-equivalent units, and at the level of the entire French market.

4.1 Track-level analysis

Our first analysis is at the level of individual tracks. In this case, we consider the impact of streaming on digital sales.

Table 4 shows the empirical results at the track level, where we regress the number of digital sales (i.e., downloads) on the number of streams. As a benchmark for comparison, the first two columns show the results from estimating Eq. (1) using the OLS and fixed effects (Within) estimators. Both regressions would suggest a positive impact of streaming on digital sales. Including the track and time fixed effects does not reduce the estimated positive association. The results from both regressions cannot be interpreted as a finding complementarity between both channels. Instead, the positive relationship may be due to the presence of demand shocks for tracks at certain points in time, which influence both the demand on the digital sales and streaming channels.

The third column shows the results after we use a price instrument for the number of streams. As expected, the first-stage demand specifications show that the volume of streams depends positively on the price of the digital track. Note that the first stage thus includes only the cross-price effect. We cannot include an own-price effect because the marginal price per stream is zero (i.e., consumers pay only a monthly subscription). See Appendix B on this point.

Thus, we only use the price of digital tracks as an instrument for the number of streams. The first-stage regression shows that the price of a digital track has a positive and significant impact on streaming consumption, which is intuitive and indicates the two channels are substitutes. Consistent with this, the 2SLS estimation of our Eq. (1) shows that streaming has a negative impact on digital track sales. An additional one thousand streams leads to 1.21 less digital track sales. This confirms the existence of some form of displacement between digital sales and streams, an effect commonly discussed in the literature.

In the spirit of Kretschmer and Peukert (2020), a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation allows us to illustrate the magnitude of the effects in terms of revenue for the music industry. To do so, we use our estimation results, the average price per track, and the average revenue per stream recently reported in various articles.Footnote 25 An increase by 1,000 streams would generate an additional streaming revenue of about 3.45€. At the same time, it displaces 1.21 digital sales, which represents 1.57€ of revenue (at an average price of 1.3€ for a digital track). Thus, an increase by 1,000 streams implies a net revenue increase of 1.88€ per track. Given that the sample consists of 6,352,178 track observations, this amounts to a total net revenue increase of about 12 million€ over the sample period (152 weeks), or approximately 4.1 million€ per year. For comparison, according to the SNEP the total revenue of the industry in France was 723 millions €in 2017.

To obtain further insights we repeat our 2SLS analysis for different subsamples, i.e., for different definitions of top tracks and different genres. Table 5 shows the results when we consider different definitions of top-selling tracks over the sample period: Top 5000, Top 1000, Top 200 and Top 50. This is of interest to assess whether streaming has somehow affected the distribution of sales (toward a longer or shorter tail). Considering the narrower top lists also serves as a methodological robustness analysis, as we have considerably fewer cases of zero sales for these lists. Table 5 shows that we obtain comparable findings across the different subsamples, i.e., streaming tends to displace digital sales. As we consider narrower top lists, the displacement seems to be stronger. For example, for the Top 200 we estimate that one thousand more streams lead to a reduction in digital sales by 2.6 units. However, because the sample size becomes much smaller the estimated standard error also increases. For the Top 50, we obtain no significant effect. These results echo a study by Savelkoul (2020) on how music piracy affects the digital sales of superstars compared to the artists from the long tail. Interestingly, the author finds a negative effect of piracy on music sales, and the effect is greater for top-selling songs compared to lower-ranked songs.

Using similar back-of-the-envelope calculations as before, we can obtain the net revenue effects for different sub-samples of tracks.Footnote 26 For a product belonging to the Top 5000, 1000 streams (3.45€ of revenue) displace 1.07 digital sales, which translates into a loss of 1.4€ of revenue per track. The net revenue increase is then 1.88€ per product. For the Top 1000, this net revenue increase is 2.06€. For the Top 200, where the estimated displacement is particularly strong, the net revenue increase is negligible, about 0.01€.

Table 6 shows the results for different genres. Displacement is estimated to be slightly lower for Pop and especially Urban Music, while it appears to be stronger for Electro. The IFPI’s (IFPI, 2020) Music Listening 2019 report highlights that “over a quarter of 16-24 years old say that the French language Urban music is their favorite genre.” Given that streaming is a type of consumption that is particularly favored by consumers in this age group, this result does not appear surprising (83 percent compared to 64 percent on average, according to the world-level statistics provided in the same report). However, because of the reduced sample sizes, the estimates are also less precise, so caution is warranted before concluding there are strong differences between genres. Overall, the findings by genres indicate that displacement is a common phenomenon, and not limited to certain specific genres.

An analysis per streaming channel highlights some interesting additional findings, as shown in Table 12 of Appendix C. All types of streaming (free audio, premium audio, and free video) displace the digital sales, but with different magnitudes: each additional thousands of free audio streams decrease the number of digital sales by 10.3 units, while an additional thousand premium audio streams decreases them by 3.8 units. Free video streaming is the channel that appears to be the least “substitutable” to digital sales.

We can conclude from these analyses that the displacement observed between digital sales and streams is not solely fuelled by one specific type of streaming, but by all of them, even though the displacement appears to be stronger with the free audio streaming.

Finally, we estimated our main model after excluding the 22 weeks which followed GfK’s change in streaming dataset construction. The coefficient of interest we obtained is \(-\) 1.30 (standard error of 0.22), which is very close to the coefficient obtained with all weeks, i.e., \(-\) 1.21 (standard error of 0.19). This suggests that our results are robust to this change.

4.2 Aggregate analysis

The track-level analyses reveal interesting findings on the extent to which the newer channel streaming displaces the older channel digital sales. However, they do not allow for a direct comparison of how digital sales and streaming differently affect the physical sales, because the physical sales of tracks are virtually non-existent, and the streaming of albums is not observed. To allow for such a comparison, we therefore consider an analysis at more aggregate levels of data. We first consider the artist-level, where we convert album sales into track-equivalent sales using the earlier discussed conversion factor of 10 tracks per album (as in Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b). Such an aggregate analysis is not only informative because it enables us to compare the relative impact of the digital and streaming channel on physical sales. It can also incorporate the impact of any possible spillover effects between different tracks and albums of the same artist.

Using a similar approach, we also consider an analysis at the French market level at the end of this section. For our aggregate analyses, we follow (Aguiar & Waldfogel, 2018b) and aggregate sales at the artist and market level. Even though we include a large set of fixed effects, we cannot exclude that our results are influenced by an aggregation bias. Therefore, the following results have to be interpreted with some caution, even though they enable us to consider consumption channels all together, and offer a convenient way to look at aggregate effects.

4.2.1 Artist-level analysis

Table 7 shows the results from the analysis at the artist-level. As in our earlier analysis at the track-level, the OLS and fixed effects regressions suggest a positive impact of both the digital channel and streaming on sales in the physical channel.

The third column of Table 7 shows the results based on our price instruments.Footnote 27 We now have two first-stage demand regressions: one for digital (track-equivalent) sales, and one for streams. Both demands may depend on the prices of digital products and physical products (and again not on the price of streams, because the marginal price of a stream is zero under the platforms’ subscription models). The estimated price effects in both first-stage regressions have the expected sign and are statistically significant. The artists’ demand in the digital channel depends negatively on the price in the digital channel, and positively on the price in the physical channel. Furthermore, the artists’ streams depend positively on both the prices in the digital and physical channels.

Based on these first-stage results, the 2SLS estimates reveal the following regarding our artist-level analysis. The digital sales channel has a negative and significant impact on the physical sales channel. Hence, after accounting for spillover effects between different tracks and albums of the same artist, the digital sales appear to crowd out physical sales. In contrast, the streaming channel shows a positive impact on sales in the physical channel at the artist level. Each additional digital track-equivalent sale reduces the number of physical track-equivalent sales by 3.4 units, at the artist level. Furthermore, each additional thousand streams increases by 14.8 units the track-equivalent physical sales, which amounts to more or less one album and a half. This points to a complementarity or demand enhancement effect. One interpretation is that streaming of certain songs provides users new information and encourages them to purchase physical products of the same artist (including other tracks or albums than the ones they streamed).

As in the track-level analysis, we also conduct our analysis for different subsamples: different definitions of top artists and different genres. A general message from these extensions is that the effects are estimated less precisely and may be statistically insignificant.

Table 13 shows the estimated effects of the digital and streaming channel for different definitions of top artists. The estimated price effects in the first-stage regressions have the expected sign and are usually significant. This translates into results that are comparable to our main specification, with a negative impact of the digital channel and a positive impact of streaming. While the coefficient on digital sales loses its significance in the subsamples, the positive impact of streaming on physical sales is significant and positive in all of them, except for the top 50.

Table 14 shows the estimated effects of the digital and streaming channels for different genres. The estimated price effects in the first-stage regressions again have the expected sign and are usually significant, suggesting that our IV approach also works properly with aggregate data at the artist level. Nonetheless, the estimated impact of the new channels on the physical channels is sometimes imprecisely estimated. In those cases where we do obtain significant estimates, they are in line with the pooled regression across genres: for Pop, streaming enhances physical sales; and for Variety, digital sales displaces physical sales, while streams enhance physical sales. Note that the positive coefficient on streaming that we obtain for these genres is in line with the findings from Aguiar (2017) and Kretschmer and Peukert (2020), who also identified a promotional effect of streaming on music sales based natural experiments.

Interestingly, an analysis per streaming channel (see Table 15) highlights that all types of streaming (free audio, paid audio and free video) promote the physical track-equivalent sales, with different magnitude: each additional thousand of free audio streams increases the number of physical sales by 143.3 units, while an additional thousand of premium audio streams increases them by 36.4 digital units. Free video streaming appears to have a positive effect of a magnitude which is close to the one observed for premium audio streams. We can conclude from these analyses that the complementary effect observed between physical sales and streams is not driven by one specific type of streaming, but all of them, with different magnitude, as observed at the track-level.

Finally, we show in Appendix D.1 (Tables 21 and 22) results obtained with alternative computation rules for track-equivalent sales.Footnote 28 Coefficients remain stable, suggesting the robustness of our initial results where each album is converted into ten track-equivalent sales.

4.2.2 Market-level analysis

For completeness, we also conducted our analysis at the most aggregate level of data: the French market level. Table 16 shows the results, based on OLS and 2SLS for the 152 weeks in our sample.Footnote 29 Both the OLS and 2SLS approaches give insignificant results, and the first-stage instruments appear to be weak at this aggregation level, except for our 4G antennas instrument which gives significant and intuitive signs.Footnote 30 We obtain similar results under different ways for computing the average prices, as shown in Table 17. One possible explanation may be the aggregation bias, as we pool together heterogeneous products (in terms of genre, formats) from heterogeneous artists (from less known to superstars). Our analysis above would then suggest that displacement and enhancement effects would co-exist, but would vary across genres and artists’ size, making it impossible at the aggregate level to find a significant effect.

5 Conclusions

The digitization of the economy impacted virtually all industries - in particular the media. The ability for consumers to consume both physical goods and digital goods raised questions about the revenues that could be generated in the long run, the business models, and the power of the various players involved. One of the central questions is related to the substitution and complementarity of the consumption of the various forms of these products, physical or digital, purchased or streamed. Even though several empirical analyses have been conducted to shed light on this question, the results are somewhat fragmented and rarely give insights on the heterogeneity of the effect across products types. Using a unique dataset that covers virtually the entire French market for recorded music, we measure the displacement between old and new distribution channels. We exploit variation in prices of tracks and albums to estimate the impact of streaming on the digital sales channel, and the impact of streaming and digital sales on the physical sales channel.

At the product level, i.e., for tracks, we show that there exists a substitution effect between the new channel (streaming) and the older channel (digital sales), consistent with previous literature. At the artist-level, we also find a substitution effect between the new (digital) and the older (physical) channel. At the same time, however, there is a general promotional effect between streaming and physical sales, that is mostly driven by the genres Pop and Variety. This suggests that artists who are positioned in specific “segments” benefited from the introduction of the streaming channel.Footnote 31 That finding complements some recent evidence in the literature (e.g., Aguiar, 2017; Kretschmer & Peukert, 2020). Finally, at the market-level, our results are inconclusive.

Our results confirm and extend previous findings from the literature by showing the robustness of the substitution effect for the products belonging to the long tail. Furthermore, they highlight the co-existence of this effect with a promotional one, at the artist level. Even though both effects (displacement and enhancement of demand) have been documented in the previous literature, our setting and unique data allow to capture them in a simultaneous way—which has not been studied before, to our knowledge. Finally, our analysis uncovers that not all genres are equal in the Digital Era—some clearly benefited much more from the introduction of the streaming channel in terms of global consumption levels. This opens an avenue for future research that could aim at identifying the “winners” and “losers” of this new state of the recorded music industry, in particular in exploring the difference between the artists associated with majors and those with indie labels. Also, diving into the role of consumer heterogeneity (age, gender) and tastes (genres, mainstream vs. indie music) can provide additional insights about the future development of the industry. For example, the return in trend of vinyls, mostly driven by the consumption of young adults, is a recent interesting phenomenon which testifies that the physical channel might survive the digitization, in forms that were not necessarily expected.Footnote 32

To conclude, this paper sheds additional evidence on the complex question of displacement and enhancement effects in the recorded music market. Yet, it calls for further investigation.

Notes

Source: International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI).

This is discussed, for example, in Datta et al. (2018).

See for example (SNEP, 2019).

Our analysis on the long tail and across genres also complements (Savelkoul, 2020) who studies the effect of piracy on music sales. He finds that the introduction of an anti-piracy law in France (HADOPI) had a positive effect on sales for all artists, superstars as well as artists who are placed lower in the sales distribution. On the same topic, in a different even though close industry, Peukert et al. (2017) exploit the shutdown of Megaupload to assess the complementarity between piracy and revenue from the box-office of various movies, highlighting the heterogeneity of effects between “star” versus “niche products.”

Some smaller players offer differentiated products such as high-quality downloads (e.g., Qobuz in France).

Data collected from various sources, including press articles and the streaming platforms’ websites, highlighted that, in France, between 2014 and 2018, all ’Standard’ subscription plans were priced 9.99€, all ’Family’ plans were priced 14.99€, ’Students’ plans 4.99 € and Hi-Fi plans 19.99€ (Quobuz HiFi and Tidal Hi-Fi).

See, for example, YouGov Music Report (2018): https://yougov.co.uk/topics/entertainment/articles-reports/2018/08/02/number-britons-illegally-downloading-music-falls; Wall Street Journal (2018): https://www.wsj.com/articles/music-piracy-remains-a-problem-in-the-spotify-era-1539118332.

In the absence of any solid metric of piracy (which can be found for the most popular products but less surely for the products belonging to the long tail), we could not identify separately the “direct” effect of streaming, and its “indirect” effect via piracy. We do, however, identify the combined, “direct” and “indirect” effects of streaming on sales.

Performance rights generate payments for the copyright owner when the song is performed (live or by a sound recording) in a public space such as nightclubs, supermarkets, or restaurants. Synchronization rights generate payments when a song is used in films, videos, commercials, etc.

We exclude the data for radio streaming because it represents a very small volume and a lot of periods are missing.

To give an idea of how they can be compared, we can mention the rule used by the National Syndicate of Phonographic Publishing (SNEP) to award certifications to singles and albums. To compute the sales, they use the rule “1 digital sale is equivalent to 150 streams” since 2016, and the rule “1 physical sale is equivalent to 1500 streams” since 2019. See https://snepmusique.com/les-certifications/a-propos-des-certifications.

Defining a reasonable threshold was a challenge as it does not exist, to the extent of our knowledge, any rule previously used in the literature or reports. Therefore, we based our final choice on our own observations from the digital stores and informal discussion with GfK. One may note that this choice of threshold does not impact significantly our final results as more than 99 percent of our observations clearly belong to one category or the other.

We also verified that our definition based on the price bounds almost always coincides with that of GfK where this was coded.

About 17 percent of digital prices and 6 percent of physical prices are imputed. We provide additional descriptive analysis in Appendix D.1 and Table 18.

Nevertheless, the censoring thresholds of 100 and 1000 streams are very mild, and only the least popular products are affected by this censoring issue.

About 18 percent of streams observations have an imputed value. We provide additional descriptive in Appendix D.1. and in Table 18. We do not extrapolate any values in order not to assume the availability of a given product on a given channel before or after its period of availability.

Since streams are correlated with digital album sales, this would involve issues of omitted variable bias. We nevertheless briefly report and discuss the product-level analysis for albums in Appendix D.4.

Finding a proxy for media exposure of a given title, album, or artist is theoretically possible. However, given the nature of our dataset which includes the hits and the long tail, and its granularity (observations are at the week-level), such proxy would be very challenging to find.

Additionally, one may use other demand determinants at the consumption channel level, such as the number of active 4G antennas which is likely to influence the consumption of streaming services, but not the number of downloads. We will use this instrument in the first-stage regression of our most aggregate model. Indeed, one can expect the 4G coverage to impact positively the consumption of streaming services, in particular in mobility. See (Aguiar, 2017) for a discussion on how streaming can bring added value to consumers through mobile consumption.

The revenue from streaming comes from the subscription fee and advertising.

We explore in Appendix D.2. such price instruments and show they do not yield conclusive results.

Revenue per stream have been documented to vary between 0.003 and 0.005 dollars. Source: https://routenote.com/blog/how-much-money-is-1000-streams. For the sake of simplicity, we take 4 dollars per thousand streams (0.004 dollar per stream), which converts to 3.45€. The average change rate observed between 2014 and 2017 is 0.8618 euro per dollar. Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/euro_reference_exchange_rates/html/eurofxref-graph-usd.en.html.

As the average price per track is homogeneous across the different samples, we use a price of 1.3€per track as previously. We also use an average revenue of 3.45€ per thousand streams.

To aggregate our price instruments, we use weighted and unweighted average prices for a given artist or week.

Based on data collected from Discogs, we computed an average number of tracks for albums belonging to different genres. We observe some heterogeneity as the average number of tracks ranges from 5.8 for the genre Electro to 10.8 tracks from Classical Music. We proceed to the aggregation after converting albums sales using the new rule—which, this time corresponds to the average number of tracks within each genre.

Note that a fixed-effects approach is no longer feasible at this aggregation level.

The first-stage regressions give no significant results, even though we obtain an intuitive negative coefficient for the price index of physical albums on track-equivalent physical sales.

At least, these benefits are in terms of units consumed. We do not claim that the artists ultimately benefited from it as the revenue sharing may be different across channels, as suggested by several reports.

See, for example, SNEP (2022) which shows that 51% of vinyls buyers are under 35 years old.

This demand system can again be derived from a quasi-linear utility function \(\sum _{i=1}^{N}U_{i}\left( q_{i}^{1},q_{i}^{2},q_{i}^{3}\right) +z\), with quadratic subutility functions \(U_{i}\left( q_{i}^{1},q_{i}^{2}\right)\).

A further analysis for different subsamples suggests this effect applies to most definitions of Top (except Top 50), and appears significant only for the genre Pop Music.

References

Aguiar, L. (2017). Let the music play? Free streaming and its effects on digital music consumption. Information Economics and Policy, 41, 1–14.

Aguiar, L., & Martens, B. (2016). Digital music consumption on the internet: Evidence from clickstream data. Information Economics and Policy, 34, 27–43.

Aguiar, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2016). Even the losers get lucky sometimes: New products and the evolution of music quality since Napster. Information Economics and Policy, 34, 1–15.

Aguiar, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2018a). Quality predictability and the welfare benefits from new products: Evidence from the digitization of recorded music. Journal of Political Economy, 126(2), 492–524.

Aguiar, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2018b). As streaming reaches flood stage, does it stimulate or depress music sales? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 57, 278–307.

Anderson, C. (2006). The long tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more. Hyperion.

Bearing Point. (2017). Evaluation de la répartition des rémunérations entre producteurs phonographiques et artistes-interprètes. Report for Direction Générale des Médias et des Industries Culturelles.

Berry, S. T. (1994). Estimating discrete-choice models of product differentiation. The RAND Journal of Economics, 242–262.

Berry, S., Levinsohn, J., & Pakes, A. (1995). Automobile prices in market equilibrium. Econometrica, 841–890.

Datta, H., Knox, G., & Bronnenberg, B. J. (2018). Changing their tune: How consumers’ adoption of online streaming affects music consumption and discovery. Marketing Science, 37(1), 5–21.

Donnat, O. (2018). Evolution de la diversité consommée sur le marché de la musique enregistrée 2007–2016. Culture Etudes, 4. Ministère de la Culture, Département des Etudes, de la Prospective et des Statistiques.

Hiller, R. S. (2016). Sales displacement and streaming music: Evidence from YouTube. Information Economics and Policy, 34, 16–26.

Hong, S. H. (2013). Measuring the effect of Napster on recorded music sales: difference-in-differences estimates under compositional changes. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 28(2), 297–324.

IFPI. (2020). Music Listening 2019: A look at how recorded music is enjoyed around the world.

Kretschmer, T., & Peukert, C. (2020). Video killed the radio star? Online music videos and recorded music sales. Information Systems Research, 31(3), 776–800.

Liebowitz, S. J. (2016). How much of the decline in sound recording sales is due to file-sharing? Journal of Cultural Economics, 40(1), 13–28.

Luca, M., & McFadden, C. (2016). How streaming is changing music (Again). Harvard Business Review.

Peitz, M., & Waelbroeck, P. (2006). Why the music industry may gain from free downloading-the role of sampling. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(5), 907–913.

Peukert, C., Claussen, J., & Kretschmer, T. (2017). Piracy and box office movie revenues: Evidence from Megaupload. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 52, 188–215.

Savelkoul, R. (2020). Superstars vs the long tail: How does music piracy affect digital song sales for different segments of the industry? Information Economics and Policy, 50, 100847.

SNEP. (2018). Bilan 2017 du marché de la musique enregistrée.

SNEP. (2019). Bilan 2018 du marché de la musique enregistrée.

SNEP. (2020a). Décryptage et performance du marché 2019 de la musique enregistrée.

SNEP. (2020b). Musique enregistrée: les performances du 1er semestre 2020.

SNEP. (2021). La production musicale française en 2020.

Waldfogel, J. (2010). Music file sharing and sales displacement in the iTunes era. Information economics and policy, 22(4), 306–314.

Waldfogel, J. (2012). Copyright protection, technological change, and the quality of new products: Evidence from recorded music since Napster. The Journal of Law and Economics, 55(4), 715–740.

Walter, J. M., & Hiller, R. S. (2019). Music consumption decisions with non-durable streaming options. Working paper.

Wlömert, N., & Papies, D. (2016). On-demand streaming services and music industry revenues: Insights from Spotify’s market entry. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 33(2), 314–327.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful for the financial and intellectual support we received from Département des Etudes, de la Prospective et des Statistiques (DEPS) from the French Ministry of Culture (Under Convention DEPS/FJJL-TSE, 2018). This project has also been funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Under Grant ANR-17-EURE-0010, Future Investment program). We thank Luis Aguiar, Tobias Kretschmer, Johannes Loh, and Yann Nicolas, as well as seminar participants at ISTO’s Research Days in Munich (2019), AFREN’s Digital Summer School in La Rochelle (2019), and AFREN’s Digital Summer School in Palaiseau (2021) for their useful comments and suggestions.

Appendices

Appendix A: Descriptive statistics

1.1 A.1 Market share

Market share of recorded music in France in Value (Data source: own computation based on GfK’s data). Note: These market shares include basket items. For the revenue of streaming, we follow Gfk’s assumption (0.01€per stream). Therefore, these market shares might not represent perfectly revenue—this is an approximation

1.2 A.2 Volumes and prices

See Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, and Table 8.

Total number of units sold and streamed over time. Note: The decline in the number of streams observed in the middle of the year 2016 is caused by a change in the dataset construction rule by GfK. We show, on the left, the number of streams used in the dataset (i.e., streams associated with a particular track). The number of streams presented on the right includes the “basket items” provided by Gfk (not associated with any specific track) which allow the compute the aggregate number of streams at the market level

1.3 A.3 Tops and genres

See Fig. 8 and Tables 9, 10 and 11.

Appendix B: Details on displacement/enhancement equations

This Appendix provides formal details on how to obtain the typical displacement/enhancement equations used in the literature (e.g., Aguiar & Waldfogel, 2018b), and Kretschmer and Peukert (2020) from an underlying demand model. We first consider the case of two channels, and then the case of three channels.

1.1 B.1 Two channels

To simplify the notation, we redefine the channels c with numbers, i.e., \(c=1\) is the (older) digital channel, and \(c=2\) is the (newer) streaming channel. Removing the time subscript t, we can rewrite the displacement/enhancement Eq. (1) for product i as:

so \(\alpha _{1}\) measures the extent to which one unit of sales from (newer) channel 2, \(q_{i}^{2}\), displaces or enhances sales from (older) channel 1, \(q_{i}^{1}\).

The main text formulated the two structural demand functions given by Eq. (4), underlying the displacement/enhancement Eq. (1). In our adapted notation, these demand functions are:

The product demands on channel 1 (digital) and channel 2 (streaming) may in principle depend on both the price on channel 1, \(p_{i}^{1}\), and channel 2, \(p_{i}^{2}\). However, in our setting, the price in channel 2 is a usage price, which is equal to zero, i.e., \(p_{i}^{2}=0\). The subscription price for channel 2, \(A^2\), does not affect the product-level demands, as we motivate further in the Remark below. This leads to the second equality in Eqs. (6) and (7), where only the price on the digital channel \(p_{i}^{1}\) enters. This price is assumed to be uncorrelated with the demand errors \(\xi _{i}^{1}\) and \(\xi _{i}^{2}\), so that it can be used as an instrument to estimate Eq. (5). Note that \(\xi _{i}^{1}\) and \(\xi _{i}^{2}\) may be correlated since other determinants can influence consumption for certain tracks on both channels. For example, radio exposure or marketing efforts such as advertising on social media could affect both digital sales (6) and streams (7).

1.1.1 Remark

To obtain this demand system, suppose a consumer maximizes a quasi-linear utility function \(\sum _{i=1}^{N}U_{i}\left( q_{i}^{1},q_{i}^{2}\right) +z\) with respect to the consumption of each product i at channel 1 and 2, \(q_{i}^{1}\) and \(q_{i}^{2}\), and the consumption of other goods z. This utility function assumes that the demands for products (tracks) are independent. Given variable prices at channel 1, \(p_{i}^{1}\), zero usage prices at channel 2, \(p_{i}^{2}=0\), a fixed subscription price for access to streaming channel 2, \(A^{2}\), a normalized price for other goods, \(p^{z}=1\), and income y, a consumer’s budget constraint is \(\sum _{i=1}^{N}p_{i}^{1}q_{i}^{1}+A^{2}+z\le y\). Utility maximization subject to this budget constraint gives the following first-order conditions for consumption of channel 1 and 2 and each product \(i=1,\ldots ,N\):

This system can be inverted to obtain demand functions \(q_{i}^{1}=f_{i}^{1} \left( p_{i}^{1}\right)\) and \(q_{i}^{2}=f_{i}^{2}\left( p_{i}^{1}\right)\). With quadratic subutility functions \(U_{i}\left( q_{i}^{1},q_{i}^{2}\right)\) and including demand error terms, this results in the linear demands (6)–(7).

To obtain the displacement/enhancement Eq. (5) from the demand system, solve the second demand Eq. (7) for \(p_{i}^{1}\) and substitute this in the first demand Eq. (6). This gives:

This reveals that \(q_{i}^{2}\) is correlated with \(\varepsilon _{i}\). Under the above assumption that \(p_{i}^{1}\) is uncorrelated with the (possibly correlated) demand errors \(\xi _{i}^{1}\) and \(\xi _{i}^{2}\), \(p_{i}^{1}\) can be used as an instrument to estimate the displacement/enhancement equation, including the parameter \(\alpha _{1}=\beta _{11}/\beta _{21}\).

1.2 B.2 Three channels

With three channels, consider the sales displacement/enhancement equation

where channel 1 now refers to physical tracks, channel 2 to digital tracks and channel 3 to streaming. The underlying (linear) demand functions depend on the price of physical tracks, \(p_{i}^{1}\), and digital tracks, \(p_{i}^{2}\) , while the (usage) price of streaming is again constant at zero, \(p_{i}^{3}=0\):Footnote 33

To obtain the displacement/enhancement Eq. (9), we solve the second and third demand equation for the two prices