Abstract

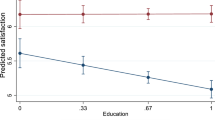

The value of the performing arts to the population can be elicited from referendum outcomes. The analyses typically rely on the (strong) assumption of full voter turnout. I show theoretically that when turnout is ignored, coefficients of variables related positively (negatively) to turnout yield upward (downward)-biased coefficients. For an empirical application, I use the example of a 2009 referendum in the Swiss canton of St.Gallen regarding the public financing of the local theater. Taking into account the turnout decision yields statistically but not economically different estimates. Bayesian model averaging suggests that income, old age, political orientation, and travel time to the theater are most closely related to the vote outcome. The analysis is complemented by comparing voter characteristics from post-ballot surveys with municipal characteristics. Voters tend to exhibit characteristics which are positive drivers of support for the referendum. This suggests that support for cultural spending among voters might be larger than among the overall population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Visitor numbers were kindly provided by the Theater St.Gallen. They are based on a visitor survey conducted in 2009.

At the time of the referendum, the SVP held 41 of the 120 seats in the cantonal parliament and was thus the party with the largest share of seats.

Personal interview with managing director Walter Signer on 20 October, 2015.

For simplicity, I refer to voters and citizens in the male form.

Subscript \(j\) reflects that utility and threshold can vary across individuals. For notational convenience I drop the individual subscript from hereon.

Even in places with compulsory voting turnout typically lies below 100%. For example, Bechtel et al. (2015) show for the canton Vaud that average turnout never exceeded 90% even when voting was compulsory.

Variables increasing the probability of turnout by definition decrease the turnout threshold T.

Travel time was collected using Google Maps. It is measured applying the “no traffic” option. Since performance typically takes place in the evenings, the assumption of little traffic is reasonable.

In Results section, I also check whether vote shares of the other three major parties have explanatory power for robustness.

This observation stands in contrast to evidence from the USA, suggesting lower turnout for less salient ballot measures. A potential explanation is the form of the voting documents: while ballot lists are the norm in the USA, each ballot measure appears on a separate piece of paper in Switzerland. Thus, there exists no predetermined ranking of measures according to, for example, importance.

The canton of St.Gallen surrounds the two cantons Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Appenzell Innerrhoden which have not voted on the theater referendum. This corresponds to the white area.

In the spirit of Hansford and Gomez (2010), I used rainfall to instrument for turnout which would vary the opportunity costs of voting. Potentially due to little variation in weather the instrument, however, turns out to be weak (F-statistics 6.70). The resulting second stage result would indicate a positive but insignificant effect on acceptance.

To conduct the Wald test, analytical weights in the regressions are required to be the same. Therefore, for the exercise of comparing the models in (9) and (10), the analytical weights from the regression in column (10) are used in both regressions. Alternatively, I used the weights from column (9) in both regressions and arrive at the same conclusions as presented here.

The respective categories for monthly income in Swiss Francs are: 1 (\(\le 3000\)), 2 (\(>3000\)), 3 (\(>5000\)), 4 (\(>7000\)), and 5(\(>9000\)).

References

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bechtel, M. M., Hangartner, D., & Schmid, L. (2015). Does compulsory voting increase support for left policy? Evidence from Swiss referendums. American Journal of Political Science, 60, 752–767.

Benito, B., Bastida, F., & Vicente, C. (2013). Municipal elections and cultural expenditure. Journal of Cultural Economics, 37(1), 3–32.

Citrin, J., Schickler, E., & Sides, J. (2003). What if everyone voted? Simulating the impact of increased turnout in senate elections. American Journal of Political Science, 47(1), 75–90.

Dalle Nogare, C., & Galizzi, M. M. (2011). The political economy of cultural spending: Evidence from Italian cities. Journal of Cultural Economics, 35(3), 203–231.

Frey, B. S. (2013). Arts & economics: Analysis & cultural policy. Berlin: Springer.

Frey, B. S., & Pommerehne, W. W. (1995). Public expenditure on the arts and direct democracy: The use of referenda in Switzerland. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 2(1), 55–65.

Getzner, M. (2002). Determinants of public cultural expenditures: An exploratory time series analysis for Austria. Journal of Cultural Economics, 26(4), 287–306.

Getzner, M. (2004). Voter preferences and public support for the performing arts: A case study for Austria. Empirica, 31(1), 27–42.

Hand, C. (2018). Do the arts make you happy? A quantile regression approach. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42(2), 271–286.

Hansen, T. B. (1997). The willingness-to-pay for the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen as a public good. Journal of Cultural Economics, 21(1), 1–28.

Hansford, T. G., & Gomez, B. T. (2010). Estimating the electoral effects of voter turnout. American Political Science Review, 104(2), 268–288.

Leininger, A., & Heyne, L. (2017). How representative are referendums? Evidence from 20 years of Swiss referendums. Electoral Studies, 48, 84–97.

Lijphart, A. (1997). Unequal participation: Democracy’s unresolved dilemma. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 1–14.

McFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In P. Zerembka (Ed.), Frontiers in econometrics (pp. 105–142). New York: Academic Press.

Mellander, C., Florida, R., Rentfrow, P. J., & Potter, J. (2018). The geography of music preferences. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42(4), 593–618.

Navrud, S., & Ready, R. C. (2002). Valuing cultural heritage: Applying environmental valuation techniques to historic buildings, monuments and artifacts. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Potrafke, N. (2013). Evidence on the political principal-agent problem from voting on public finance for concert halls. Constitutional Political Economy, 24(3), 215–238.

Rushton, M. (2005). Support for earmarked public spending on culture: Evidence from a referendum in metropolitan Detroit. Public Budgeting & Finance, 25(4), 72–85.

Sanders, M. S. (1998). Unified models of turnout and vote choice for two-candidate and three-candidate elections. Political Analysis, 7(1), 89–115.

Schneider, F., & Pommerehne, W. W. (1983). Private demand for public subsidies to the arts: A study in voting and expenditure theory. In W. S. Hendon & J. L. Shanahan (Eds.), Economics of cultural decisions (pp. 192–206). Cambridge: Abt Books.

Schulze, G. G., & Ursprung, H. W. (2000). La donna e mobile—or is she? Voter preferences and public support for the performing arts. Public Choice, 102(1–2), 129–147.

Staatskanzlei St.Gallen (2009). Volksabstimmung vom, 27. September 2009. Kanton St.Gallen.

Throsby, C. D. (1984). The measurement of willingness-to-pay for mixed goods. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 46(4), 279–289.

Throsby, C. D., & Withers, G. A. (1986). Strategic bias and demand for public goods: Theory and an application to the arts. Journal of Public Economics, 31(3), 307–327.

Trechsel, A. H., & Sciarini, P. (1998). Direct democracy in Switzerland: Do elites matter? European Journal of Political Research, 33(1), 99–124.

Wheatley, D., & Bickerton, C. (2017). Subjective well-being and engagement in arts, culture and sport. Journal of Cultural Economics, 41(1), 23–45.

Wolfinger, R. E., & Rosenstone, S. J. (1980). Who votes?. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for comments received from Niklas Potrafke and Lukas Schmid, as well as participants at the International Conference on Cultural Economics 2016 in Valladolid.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof

The probability of voting for referendum \(r\) is:

Normalizing \(\beta _q=1\), dividing everything by \(e^{\beta _r X}\) and rearranging yields:

I define \(Z=\beta _r X - \gamma W\) and write the voting probability as \({P={\mathrm{Prob}}({\mathrm{vote}}=r)}\). Solving Eq. (6) for \(e^Z\) results in:

Taking the natural logarithm on both sides and substituting back for \(Z\) yields:

To account for the fact that individual voting probabilities are unknown to the researcher and only aggregate voting data at municipal level are available, sample means are used for the estimation. Denote the number of citizens in municipality \(m\) by \(c_m\) and the number of yes votes by \(y_m\). The probability of voting yes in a given municipality is then defined as \(\hat{P}_m =y_m/c_m\). Substituting into Eq. (8) yields the following estimation equation:

\(X_m\) and \(W_m\) are explanatory variables at municipal level related to vote choice and turnout. \(\epsilon _m\) denotes the error term.

1.2 Data sources

1.3 Turnout evidence from federal post-ballot surveys

This section complements the main analysis and compares voter characteristics with municipal averages of socioeconomic variables. After all federal voting days in Switzerland post-ballot surveys, the VOX surveys are conducted. Randomly selected citizens are contacted by telephone and asked about their voting decisions as well as a wealth of personal information. The questions only concern federal referenda, so the survey cannot be used to analyze preferences for the cantonal vote. However, the turnout decision on a given voting day is highly correlated between the various measures taking place on the same day. The survey can therefore be utilized to explore the characteristics of the voting population and compare it to the total population.

Income, education, and age are variables collected during the survey which coincide with variables used in the above regressions. I therefore compare the descriptive statistics from municipal data with the ones from survey respondents. I use only respondents who reported to have voted. Income is reported in five categories in the survey. I translate the average municipal monthly income into the five categories to make it comparable to the survey.Footnote 15

The numbers are presented in Table 7. The first three columns refer to respondents from German-speaking cantons. While these voters need not be representative of the canton of St.Gallen, this sample selection ensures a sufficient number of observations. The following three columns are based on respondents from the canton of St.Gallen. The last three repeat municipal used in the aggregate analysis for comparability. T-statistics for the hypothesis that sample averages are equal to the cantonal averages are in parentheses. Comparing the German-speaking sample with the cantonal descriptives shows a clear trend: voters on the September 27, 2009, were significantly richer, better educated, and older than the average population. The comparison for the sample from the canton St.Gallen should be interpreted carefully because the number of observations drops from more than 300 to only 30. While the values of all three variables are larger in the St.Gallen sample than among average citizens, the difference is significant for income and marginally insignificant for the share of older people.

The exercise provides suggestive evidence specifically for the voting day the St.Gallen Theater referendum took place that voters differed from average citizens in terms of variables that are positively related to preferences for cultural spending. Therefore, voters could be expected to be more supportive of cultural spending than average citizens.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hofer, K.E. Estimating preferences for the performing arts from referendum votes. J Cult Econ 43, 397–419 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09341-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09341-8