Abstract

To reach the goal of large-scale seaweed cultivation in Norway and the rest of Europe, new knowledge about the commercially important kelp species Saccharina latissima is needed. Efforts to maximise biomass by outplanting the seaweed in different seasons can affect seaweed quality. Here, we investigate the effects of outplanting time (February, April, and May) when cultivating S. latissima in the northern range of the species’ distribution. We studied the quantity and quality of the seaweed biomass produced in the autumn following outplanting. Effects on quantity were evaluated as seaweed frond area, relative daily growth rate (DGR) and relative daily shedding rate (DSR). Quality was evaluated by tissue content of carbon and nitrogen compounds and number of fouling epizoans. Cultivation was successful when seedlings were outplanted in both February and April, but not in May. An earlier outplanting, in February, gave a prolonged time for grow-out at sea prior to the main recruitment event of epizoans that occurred in September, thereby earlier outplanting resulted in larger frond areas. The frond area reached in September was doubled when seedlings were outplanted in February compared to April, whereas a later outplanting in April gave a higher DGR and DSR, higher carbon content, and lower amount of fouling epizoans. The outplanting season did not affect tissue nitrate concentration or internally stored nitrate. These results show that outplanting time is an important factor to consider especially for biomass yield, but also for seaweed quality, including epibiosis of the seaweed biomass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to a steadily increasing food and energy demand, the UN have declared 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) for 2030. Seaweed aquaculture can contribute to several of these (SDG 2 – zero hunger; SDG 3 – good health and well-being, SDG 12 – Responsible consumption and production; SDG 13 – climate action; SDG 14 - life below water) (Custódio et al. 2020; FAO 2020), by producing nutritional and healthy biomass (García-Poza et al. 2020) and supporting ecosystem services such as removal of dissolved inorganic nutrients and carbon dioxide, decreasing eutrophication and acidification of coastal waters (Jiang et al. 2020), and habitat provision (Visch et al. 2020a, 2020b). In 2018, seaweed aquaculture (red, green and brown algae) accounted for 32.4 million of 114.5 million tonnes of biomass from aquaculture and 13.3 billion of 263.6 billion US$ (FAO 2018, 2020). Presently the bulk of this seaweed production occurs in six Asian countries (Chopin 2014) but is also one of the fastest growing industries in countries with developed economies (Buck et al. 2017).

In the northwest Atlantic Ocean, sugar kelp, Saccharina latissima (L.) C.E. Lane, C. Mayes, Druehl, and G.W. Saunders, is the preferred cultivated seaweed because of its high growth rate (Handå et al. 2013; Bak et al. 2018; Sharma et al. 2018), valuable tissue content (Marinho et al. 2015; Stévant et al. 2017; Sharma et al. 2018), and a life cycle that can be regulated (Forbord et al. 2012). In China, sporelings are outplanted in autumn when the seawater drops below 20 °C (Tseng 2001, 2004). In Europe, different cultivation procedures were launched in the 1980s and 1990s (Druehl et al. 1987; Kain and Dawes 1987; Druehl et al. 1988; Kain et al. 1990). However, the industry itself is still in its infancy in Europe, and the conditions under which quantity and quality of the yield can be maximised are not well known. Yet, optimisation for these conditions is essential for establishment and further development of seaweed aquaculture. Depending on location and latitude, the cultivation period for this species is determined by seasonal changes of environmental parameters (i.e., light, temperature, and nutrients) that affect growth and build-up of desirable chemical compounds (Broch et al. 2019; Forbord et al. 2020). At the same time, variations in growth and quality have been recognised to vary spatially on metre to kilometre scales (Visch et al. 2020b) and with latitude (Forbord et al. 2020). Saccharina latissima grows optimally within 10–15 °C and at light levels above 70 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Fortes and Lüning 1980). In winter at 69 °N, above the Arctic circle, the sea water temperatures are below 4 °C (Matsson et al. 2019) and the sun do not rise above the horizon until late February. Therefore, the effect of outplanting of S. latitissima in its northern range of the species’ distribution in Norway can vary from other more southern locations.

The quantity and quality of produced biomass is affected by the chemical composition, growth and shedding rates of S. latissima. Both quality and quantity are regulated by a combination of abiotic factors and their seasonal interactions, along with biotic factors such as life stage and age of the seaweed sporophyte (Bartsch et al. 2008; Roleda and Hurd 2019; Forbord et al. 2020). Nitrogen (N) most commonly limits seaweed growth (Roleda and Hurd 2019) and variations in seaweed growth rates correspond to variations in ambient nitrogen supply and internally stored nitrate (Bartsch et al. 2008). Seasonal N fluctuations are high in the Arctic and N is usually limited in summer (Hurd et al. 2014). The C:N ratio can vary from 5 to 40 for different macroalgae, where values above 10–15 indicate possible nitrate-limited growth, and values below that ratio indicate storage of nitrogen (Hanisak 1983). When environmental nutrient concentrations are high (i.e., in winter in temperate regions) Laminariales, including S. latissima, can store nutrients that can be used for growth later when ambient nutrient levels decrease. Additionally, sporophytes with higher tissue N can exhibit higher protein content (Mortensen 2017; Forbord et al. 2020), in turn an indicator of seaweed quality. Later in summer when water temperature increases, light availability is high, and nutrients are depleted in surface layers, the seaweeds store energy in carbohydrates (Black 1950). Consequently, seaweed yield and quality vary with ambient environmental conditions particularly in the highly seasonal Arctic (Bartsch et al. 2008). Following seasonal environmental changes, epizoans (i.e., sessile epibiotic animals (Wahl 1989)) begin to attach to the seaweed surface, altering seaweed biomass quantity and quality (Matsson et al. 2019; Forbord et al. 2020), and these epizoans limit the cultivation period. The end-product will therefore be affected by the timing of outplanting and harvest (Peteiro and Freire 2012; Bruhn et al. 2016; Forbord et al. 2020). In Europe, much research is focused on maximising seaweed biomass yields by optimising the timing for growth and quality for the intended end-products. It is, therefore, of high interest for seaweed farmers to be given guidelines on outplanting and harvest times that maximise quality and minimise biomass loss.

Epizoan species composition and peak abundance may vary with season and location (Wahl 1989; Hepburn et al. 2006; Forbord et al. 2020). The bryozoan Membranipora membranacea (L.) is one of the most common epizoans fouling seaweed fronds (Saunders and Metaxas 2009; Marinho et al. 2015; Forbord et al. 2020). Its hard calcium carbonate skeleton deteriorates the seaweed quality and compromises the structural integrity of the frond, causing up to 100% loss of biomass (Krumhansl et al. 2011; Skjermo et al. 2014). Seaweed frond elongation occurs at the base/meristem while the tips are shed continuously, and fronds of Laminariales can turnover 1 to 5 times a year (Mann 1973). Fouling organisms are thereby removed with the shed seaweed tissue, and growth and shedding rates can reduce amount of epizoans.

Here we examined the effect of outplanting time (winter to spring) of S. latissima in the northern range of the species’ distribution by measuring the quantity (frond area, growth and shedding rates) and quality (tissue content of carbon and nitrogen compounds and density of epizoans) of seaweed biomass produced the following autumn. We hypothesised that earlier outplanting would (1) result in higher content of nitrogen components in kelp tissue due to higher ambient nitrate concentrations at the time of outplanting and (2) produce larger frond areas, prolong the seaweed growth season, and increase rate of shedding, and thereby also (3) affect the occurrence of epizoans and bryozoan settlers. Considering the commercial importance of S. latissima, this trial has an industrial application in that it will provide important information on the cultivation of this species in its northern distribution range in the Norwegian Sea.

Methods

Material collection and site

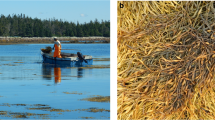

Seedlings of Saccharina latissima were prepared for three outplanting dates (February, April and May 2018). Parent plants with sori were collected for the February outplanting on 5 January 2018 at the harbour in Tromsø (69° 39′ 07′′ N/18° 57′ 48′′ E). Parent plants without sori were collected for the April and May outplantings from a seaweed cultivation site nearby Kvaløya (69° 45′ 21′′ N 19° 02′ 17′′ E) on 31 October 2017 and 21 February 2018, respectively. Fertile sorus tissue was induced, when not occurring naturally, by removal of the basal blade meristem, and kept in tanks indoors with running seawater from 30-m depth and a 16:8 h day:night regime as in Forbord et al. (2012). To ensure contaminant-free spore release, sori were disinfected with 5% NaHCl (Rød 2012), blot-dried with paper towels and transferred to zip-lock bags for 24 h. The disinfected and dehydrated sori were sent to SINTEF Sealab in Trondheim for spore release (number of fertile sporophytes: N = 14, N = 9 and N = 13 for the first, second and third outplantings, respectively). A solution containing ~250.000 spores mL−1 (February and May outplantings) or ~ 150.000 spores mL−1 (April outplanting) was sprayed onto a 1.2-mm diametre twine coiled around six PVC spools per outplanting. Although the spore density of the solution differed between outplantings, spraying to full saturation in all cases provided a high likelihood of similar density and high density, though sporeling density was not determined. From more than a decade of experience, the producing lab’s staff observed similar size of sporelings when sprayed on ropes (Forbord pers. com.); actual size was not measured. The twines were then incubated and grown under identical conditions for 6 weeks in nutrient-rich seawater (148 μg NO3− L−1, 20.6 μg PO4 L−1) in a flow-through (120 L h−1), light- and temperature-controlled system at the seaweed hatchery (70 μmol photons m-2 s−1 at the surface and 10 °C) as in Forbord et al. (2018). The spools with best seedling growth were packed in polystyrene boxes and express-shipped to Tromsø, where they were spun around 14-mm diametre ropes tightly to ensure high density of sporelings in all treatments. They were outplanted (Fig. 1) on the day of arrival (21 February, 4 April and 15 May).

Each outplanting consisted of seven vertical ropes attached to a horizontal carrying rope (Fig. 2) with seaweed seedlings spread at 1–2 m depth, for a total of 21 ropes. Each rope had a 1-kg weight at 2-m depth. The farm was situated at ~100 m from the shore.

Experimental set-up with 7 vertical ropes per outplanting date, seeded with S. latissima at 1–2 m depth (not at scale). Each rope was attached to a buoy (yellow circles), placed approximately 6 m apart on a horizontal carrying rope. Marker buoys (orange dots), weights and mooring ropes (grey squares and grey lines) formed the cultivation rig

After 3 weeks, most sporelings from the May outplanting had disappeared, possibly because the spring bloom covered the ropes with other algae competing for light and nutrients. However, there were some surviving sporophytes for the last census of the experiment in September.

In June, there was an observed difference in density between the two earliest outplantings, with a higher sporophyte density in the February outplanting compared to the April outplanting. This was most likely an effect of self-thinning. To achieve an even distribution of seaweed along the ropes, density was thinned to 100 individuals per metre rope on 8 June by removing individuals, including the very smallest ones (≤10 cm in length).

Data collection and analyses

Environmental variables

Temperature (°C) and light intensity (Lux) were recorded at 2 m depth from 9 March to 5 September 2018 every 15 min using Onset HOBO pendant loggers (USA; temperature accuracy ±0.53 °C, resolution 0.14 °C) fixed to the rig (Fig. 2). The Lux measurements were converted to PAR using the relationship PAR = 0.0291 Lux1.0049 (Long et al. 2012; Broch et al. 2013). Loggers were cleaned at every sampling date to minimise the effect of fouling.

Samples for ambient (extracellular) nitrate (E-DIN) concentration were collected using a Ruttner water sampler (N = 3, per sampling period).

Tissue composition

Samples for total tissue nitrogen (QN), intracellular nitrate concentration (I-DIN), and carbon (C) analyses were collected once to twice per month. Six seaweed fronds (without the stipes) were haphazardly collected from each of the seven replicate ropes on every sampling date from 2 May for the February outplanting, from 16 May for the April outplanting and until 5 September for both outplanting. The May outplanting only had enough biomass for one sampling date at the end of the experiment. The samples were shaken for 30 s to remove excess water and placed in pre-marked plastic zip-lock bags and plastic bottles. On shore, the samples were put into a −18 °C freezer and stored until analysis.

Fouling organisms were removed and the middle of the seaweed fronds was selected for all nutrient analyses modified from Forbord et al. (2020). Briefly, for analysis of intracellular nitrate content (I-DIN), 0.06 g semi-frozen S. latissima material from each sample was placed in test tubes with 6 mL of distilled water, boiled for 30 min (with marbles at the surface to prevent evaporation), cooled, filtered into 15-mL plastic tubes using a 0.45-μm polysylfone syringe filter and diluted by mixing 0.3 mL of the solution with 9.7 mL distilled water. The tubes with the diluted solution were placed in a −20 °C freezer until further analysis. Prior to analysis, the tubes were defrosted and shaken. E-DIN and I-DIN were analysed by standard seawater methods (Randelhoff et al. 2018) using a Flow Solution IV analyser from O.I. Analytical, USA. The nutrient analyser was calibrated using reference seawater from Ocean Scientific International Ltd. UK.

Total tissue C and N were analysed by drying samples at 60 °C for 24 h. The dried samples were homogenised and pulverised, and 0.55–0.75 mg weighed into 6 × 2.9 mm tin capsules using a Mettler Toledo MX5 ultra-microbalance and analysed with a CHN elemental analyser (Leeman Lab CEC 440 CHN analyser) with acetanilide as standard.

The dry weight (DW) of the sporophytes used for I-DIN calculations was calculated by measuring the wet weight (WW) and DW of three individuals per rope from each outplanting harvested the 17 July (DW = 0.14 g g−1 WW, SE 0.0047).

Seaweed growth (frond area, DGR and DSR)

The area of the frond was estimated from length and width measurements, corrected for frills. The correction factor was estimated based on the relationship of frond length and width to actual area as in Yorke and Metaxas (2012). The seaweed frond was cut into small pieces and laid flat on a white background, and each section was photographed with an Olympus Tough F2.0 digital camera. The pictures were analysed in ImageJ (Schneider et al. 2012) and total area and frond areas were calculated as follows:

where L is the total frond length and W is the width of the widest part of the frond.

The hole-punching method (Parke 1948) was used to measure gross growth in frond length and loss through shedding of the seaweed frond. A hole was punched 5 cm from the transition between the stipe and the frond on 6–10 haphazardly chosen individuals from each of the seven replicate ropes in each treatment. A new hole was punched once to twice every month and the distance between the new and the old holes and between the old holes was measured. To minimise the impact from handling on the fragile fronds, hole punching was initiated when the sporophytes were considered robust enough (2 May and 8 June for the February and April outplantings respectively).

From the distance measurements between holes, the relative daily growth rate (DGR), and relative daily shedding rate (DSR) were calculated as follows:

where L0 is the total frond length on the previous sampling date, Lt is the total frond length on the following sampling date, G is gross frond growth since previous sampling, calculated by adding the length increase between the punched holes, and t is days since last sampling date.

Epibiosis (total, species and M. membranacea settlers)

At each sampling date, three sporophytes per rope were collected haphazardly and kept moist and cool until analysis. The seaweed frond was divided into three equally long sections representing meristematic, middle, and distal (tip) regions to test for effects of frond age on epizoans, and the number of epizoan individuals/colonies was identified and counted. Colonies of the abundant bryozoan M. membranacea were subdivided into two size classes: < 2 zooid rows were categorised as (early) settlers and ≥ 2 zooid rows as colonies as in Saunders and Metaxas (2007), using magnifying eyewear (Watch Repair Magnifyer) (× 25). When a colony covered two frond areas, it was included in the frond area nearest the stipe.

Statistics/data analysis

The effects of timing of outplanting (fixed factor, three levels) and date (random factor, seven levels) on QN, I-DIN, C:N and C were examined with a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Outliers for QN and C were removed because the very low values were assumed to be the result of an analysis error. The data were normally distributed for most variables (except for I-DIN on 7 June, 17 July, 1 August and 13 August for the February outplanting and 7 June for April outplanting, C:N on 16 May for February outplanting and 7 July for April outplanting), as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > 0.05). Variances were homogeneous (p > 0.05) for most variables (except for carbon p = 0.047, and C:N p = 0.003), as assessed by Levene’s test. Significant differences between means were examined using post hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections. Relationships between E-DIN, I-DIN and QN were examined using linear regression, including a potential time-lag effect of external nitrogen tested using E-DIN data from succeeding sampling date (‘delayed E-DIN’). ANOVA was used to examine the effects of the effects sampling date (repeated measures, random factor, five levels) and outplanting time (fixed factor, two levels) on the DGR and DSR. The data were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk’s test (p > 0.05) and variances were homogeneous (p > 0.05) for most data, as assessed by Levene’s test. For the repeated measures ANOVA, Mauchly’s test was used to test the assumption of sphericity, which was met for DSR but not for DGR; therefore, p values for tests were adjusted using the Greenhouse-Geisser corrections (Queen et al. 2002).

Two-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of outplanting time (fixed factor, three levels) and date (random factor, 5 levels) on the amount of epizoans. Most data were normally distributed as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk’s test (p > 0.05), except data from the initial colonisation in the April outplanting (28 June; p = 0.012, 17 July; p < 0.001, 1 August; p = < 0.001) and February (28 June; p = 0.006). The data were log-transformed without much improvement. Three-way ANOVA was used to examine the effects of outplanting time (fixed factor, two-three levels), sampling date (random factor, five levels) and frond section (fixed factor, three levels) on the dependent variable M. membranacea settlers. In cases where the variances were heterogeneous or deviated from normality, data were log-transformed which yielded little improvement. Since ANOVA is relatively robust to heterogeneity of variance when group sizes are approximately equal (Jaccard and Jaccard 1998) and to deviations from normality (see Maxwell et al. (2017)), the two-way ANOVA was done on the untransformed data. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistical software (Version 25) and graphs produced by using R, version 3.5.1 (R Core Team 2018) through RStudio version 1.1.456 (RStudio Team 2016).

Results

Environmental data

Water temperature gradually increased from 2.9 °C on 9 March to 3.7 °C by 4 April (April outplanting) and 5.2 °C by 15 May (May outplanting) (Fig. 3, left y-axis). By the end of July, seawater temperatures were rather stable at ~10 °C. The average daily irradiance in PAR increased rapidly from February onwards with increasing day length with an average of 32, 81 and 116 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at the February, April and May outplantings, respectively (Fig. 3, right y-axis). From mid-May until the end of June, measured irradiance decreased, most likely because of shading caused by phytoplankton bloom and fouling on the loggers. E-DIN was highest in April (Fig. 4) and steadily decreased to less than 0.1 μM in August, when it started to increase again.

Extracellular nitrate (E-DIN) (μM) measured in the water column at 69° N at 1 m depth (black line), intracellular nitrate (I-DIN) (mg NO3− g−1 DW) (dotted line), and total nitrogen content (QN) (mg N g−1 DW) (stippled line) of S. latissima fronds. The arrow shows when the ropes were thinned. Mean ± SE, n = 3

Tissue composition

QN ranged from maximum mean values of 2.4 mg N g−1 DW in May to a minimum of 0.78 mg N g−1 DW in the beginning of August, and was significantly affected by date (Fig. 4, Table 1). I-DIN peaked in June with maximum mean values of 0.96 mg NO3− g−1 DW for the February outplanting and 0.51 mg NO3− g−1 DW for the April outplanting, and minimum values for both outplantings in August. There was a significant interaction of outplanting time and sampling date on I-DIN (Fig. 4, Table 1) and a significant effect of sampling date on I-DIN, and I-DIN storage was greater for the February than the April outplanting. After June, these elevated levels of I-DIN were reduced to similar levels between outplantings. Both I-DIN and QN were affected by the fluctuations of E-DIN (Table 2), where the variance of QN was better explained by E-DIN than by I-DIN. Both I-DIN and QN had a delayed response (2–3 weeks, i.e. subsequent sampling date) to changes in E-DIN (Table 2).

C:N ratios increased from low values around 10 in May to peak values of 30–40 in August (Fig. 5a). There was a significant interaction between outplanting time and date on C:N ratio (Table 1). C:N ratio increased over sampling time, until the last sampling, where the E-DIN levels started to rise (Figs. 4 and 5a). C:N ratio was higher for the April than the February outplanting from mid-July to mid-August (Table 1) and both were higher than the May outplanting in September (Table 1).

Tissue carbon content was significantly affected by both outplanting time and date (Fig. 5b, Table 1), increasing with time and being higher for the seaweed outplanted in April compared to February.

Seaweed growth (frond area, DGR and DSR)

Frond area increased with time (Fig. 6a). The initial absolute growth was higher for the April than the February outplanting from outplanting date until the first sampling (at day 70 for the February outplanting and day 65 for the April outplanting), but the opposite was the case over the entire study period (196 and 154 days, respectively). Fronds were longest on the last sampling date (5 September) for both the February (147.8 ± 7.65 cm) and the April outplantings (87.5 ± 4.70 cm) (n = 7), compared to 26.8 ± 5.43 cm (n = 6) for the May outplanting. The length to width ratio (L:W) was consistently higher for the February than the April and May outplantings throughout the study period, with 6.1 ± 0.08 compared to 4.5 ± 0.07 and 4.5 ± 0.21 (mean ± SE, n = 455; 288; 24) (Electronic Supplementary Material 1).

a Area of the seaweed frond in m2 as an effect of days in the sea, mean ± SE, n = 7. b Relative daily growth rate (DGR) in length for Saccharina latissima outplanted in February and in April at 69° N (positive values) and relative daily shedding rate (negative values) as lost algae material in length. Mean ± SE, n = 7

Relative DGR was significantly greater for seaweed outplanted in April than February and was significantly affected by date (Fig. 6b and Table 3), with higher rates in early than late summer. Relative DSR was also significantly higher for the seaweed outplanted in April than February and decreased from June to early August for both outplantings (Fig. 6b, Table 3), though there was no significant relationship between DSR and DGR (See Electronic Supplementary Material 2).

Epibiosis (total, species and M. membranacea settlers)

Epizoans were first observed in late June, then their abundance increased slowly until a main fouling event occurred before the last sampling in September (Fig. 7a). Epizoan density peaked 6.5 and 5 months after outplanting for the February and April outplantings, respectively (Fig. 7a). There was a significant interaction between outplanting time and sampling date for the number of epizoans per area kelp frond (Fig. 7a and b, and Table 4). Abundance of epizoans was significantly different among outplanting treatments in September only (Table 4). The number of fouling organisms per area at the last sampling in September was not affected by the total area of the seaweed (Fig. 7b).

Five species were attached to the S. latissima fronds: the hydroid Obelia geniculata, the bivalve Mytilus edulis, the barnacle Balanus sp. and the bryozoans Membranipora membranacea and Electra pilosa (Fig. 8b) but M. membranacea was the most abundant epizoan for all outplantings and dates. The relative contributions in total epibiosis abundance by E. pilosa were highest in early summer but only for the February outplanting, and were succeeded first by M. edulis and then O. geniculata which contributed substantially in August–September. Filamentous algae (not quantified) first occurred on kelp tips of the February outplanting in June and to a lesser extent on the April outplanting; by the last sampling in September, they were similar for all three outplanting times. There were significant interactions between frond section and outplanting time, and between frond section and sampling date for the number of M. membranacea settlers (Table 5). More settlers were present on the young meristematic region than on the middle region and the tips for the February treatment. More settlers were present on the meristematic region than the tips for the April treatment, and more settlers were present on the mid-section than the meristem for the May outplanting (Fig. 8c). Also, the number of settlers at each section was highest for the February outplanting and lowest for the May outplanting. Only in September was the number of M. membranacea settlers highest on the meristem and lowest on the tips for all outplantings.

Organisms fouling Saccharina latissima outplanted at three different times (F:February, A:April and M:May) from 28 June until 5 September. a Density (number of epizoans m-2 kelp) over time for the three outplanting dates. Mean ± SE, n = 7. b Relative composition of epizoans for each sampling date: Balanus, Balanus sp.; Mytilus, Mytilus edulis; Electra, Electra pilosa; Hydroids, Obelia geniculata; Membranipora, Membranipora membranacea. c Settlers of M. membranacea relative abundance on three frond sections for the three different outplanting times. Kelp outplanted in May was only sampled 5 September

Discussion

In this study, cultivation of S. latissima at 69° N was successful when outplanted in both February and April, but not in May. Our results generally supported our hypothesis that quantity and quality of harvestable seaweed are affected by outplanting time, but this effect was not consistent across all examined variables or across the entire sampling period.

Tissue composition

There was no difference in total tissue nitrogen, QN, among outplanting times, and the initially elevated levels of intracellular nitrate, I-DIN, for the February outplanting were utilised fast when extracellular nitrate, E-DIN, dropped. These results were contrary to our hypothesis that earlier outplanting with accompanying elevated E-DIN would result in a higher content of intracellular nitrogen components (QN and I-DIN) in S. latissima. This result is also in contrast to a previous laboratory study with the same kelp species where nutrient depletion in the tissue did not occur until 9 weeks in nutrient replete water (Lubsch and Timmermans 2019). Similarly, depletion of the intracellular nitrate storage in Laminaria longicruris in Nova Scotia, Canada, followed the disappearance of the external nitrate with a lag period up to 2 months (Chapman and Craigie 1977). The reason for the fast depletion of I-DIN in the present study may be that initial E-DIN concentrations were comparatively low, resulting in the internal-tissue nutrient pools and other N-compounds not being filled up before the external nutrient levels dropped to a minimum. The storage of I-DIN in S. latissima is a slow process (Forbord et al. 2021), and this species tends to store nitrate when the ambient nitrate concentrations are higher than 10 μM (Chapman et al. 1978), levels never recorded in our study (Fig. 1).

I-DIN and QN concentrations followed a seasonal pattern, as also found by Forbord et al. (2020) across Norway, being highest in the beginning of the sampling period, when extracellular nitrate levels were also highest before summer stratification, and before the phytoplankton spring bloom reduces the E-DIN (Ibrahim et al. 2014). Both QN and I-DIN were, as hypothesised, significantly affected by the availability of extracellular nitrate (E-DIN) throughout the sampling period and as a result were also correlated with each other. I-DIN dropped to near zero in July, when QN dropped below 10 mg N g−1 DW, which is likely because QN values exceeding 1% of DW (or 10 mg N g−1 DW) allow internal storage of nitrate in S. latissima (Asare and Harlin 1983). Both the incorporation of nitrogen in the seaweed tissue (QN) and the intracellular storage of nitrate (I-DIN) responded with a 2–3 week delay relative to the altered levels of nitrate available in the water column. QN in members of the Laminariales order follow ambient nitrate level at various time lags (Chapman and Craigie 1977; Wheeler and North 1980, 1981). Protein content is another indicator of kelp quality and based on an average nitrogen-to-protein conversation factor (Kp) for the present location of 3.9 ± 0.3 (mean ± SE) (Forbord et al. 2020), protein concentration was estimated at 99 mg g−1 DW proteins in June and declined to less than one third (30 mg g−1 DW) 2 months later for all outplanting treatments. Thereby, supplying a higher protein yield if the seaweed biomass is harvested earlier in the season.

While outplanting time did not affect nitrogen components, it did affect carbon content. Sporophytes outplanted in April had a higher carbon content and a higher C:N ratio than those outplanted in February, suggesting a higher accumulation of carbohydrates for the former. Photosynthetic rates are affected by biotic factors such as morphology, ontogeny, age, and circadian rhythms (Hurd et al. 2014), and the assumed higher surface area:volume ratio of the smaller April sporophytes may contribute to a higher photosynthetic rate, resulting in higher carbon content and also higher growth rates (Littler and Arnold 1982). In contrast, older individuals of a related species, Laminaria hyperborea, can have a higher C:N ratio than first-year sporophytes (Sjøtun et al. 1996). The critical nitrogen concentration (QN) to sustain maximum growth rate in S. latissima is ~1.9 % of DW (Chapman et al. 1978). When nitrogen content is above that value, carbon content is positively correlated to the nitrogen content for Saccharina japonica (Mizuta et al. 1997). This is consistent with the stable C:N ratio of ~10 in our study which persisted until the beginning of July for both outplantings in the present study. Carbon content increased over time for all outplanting dates when irradiances was higher and seaweed growth rates slower. This pattern suggests an accumulation of carbohydrates in summer when reserve carbon storage compounds increase (Sjøtun 1993; Azevedo et al. 2019).

It is possible that the higher initial density of sporelings in February than other outplanting dates may have introduced some confounding effects on the results. An increased competition for resources with an accompanied reduction in carbon and nitrogen tissue (QN) content can occur in dense seaweed stands (Creed et al. 1998; Svensson et al. 2007). However, this did not appear to be the case in the present study. In fact, the seaweed of the February ouplanting before the thinning event demonstrated a higher I-DIN, similar QN and carbon content than the lower-density April outplanting. Post-thinning, when both outplantings had similar densities, the initially thinner April outplanting treatment was more nitrogen limited (as evidenced by significantly higher C:N on two dates) than the February one. Post-thinning, the April outplanting also had a higher relative growth rate than the February one, consistent with previous studies showing that smaller individuals have a faster growth rate (Creed et al. 1998). Additionally, variations in biomass have been shown to not influence epibiotic species richness and composition (Walls et al. 2017). We conclude that the initially unequal density of spore solution, while not ideal, was unlikely a cause of different sporeling density in June, but rather an effect of self-thinning and further that the thinning 8 June did not affect the results as the trends in relative DGR and DSR and chemical content were consistent throughout the remainder of the study period.

Seaweed growth (frond area, DGR and DSR)

In support of our hypothesis, frond area was larger throughout the experiment in seaweed outplanted in February than April and May. In Asia that has a longer seaweed cultivation tradition than Europe, similar studies investigating the effect of earlier outplanting showed that outplanting young sporophytes earlier in the season at lower temperatures can both inhibit competition with other seaweeds and more than double the seaweed yields due to the extended grow-out phase in sea (Tseng et al., 1955).

Earlier studies of the cultivated Laminariales, S. latissima, L. digitata and Undaria pinnatifida, at 43° N to 70° N show a similar trend with increased production in yield when outplanted earlier in the season (e.g. Peteiro and Freire 2009, 2012; Edwards and Watson 2011; Handå et al. 2013). In contrast, one study in the UK reported a lower biomass production in S. latissima when outplanted in November compared to December and February (Kain et al. 1990).

Contrary to our hypothesis, however, earlier outplanting did not result in an increased relative DGR through the summer. In fact, DGR was significantly higher when kelp was outplanted later (April) than earlier (February). Given that the younger and smaller individuals from the April outplanting had a higher carbon content and, in summer (July to August), a higher C:N, indicating nitrogen limited growth; thus, the higher DGR in the April outplanting may be due to processes not restricted by nitrogen. One possible explanation is that younger individuals of several Laminariales species, including S. latissima, exhibit age-specific seasonal growth, with a prolonged duration of high vegetative growth in summer (Lüning 1979; Druehl et al. 1987), and the triggering mechanisms for seasonal growth for many kelp species is an underlying endogenous circannual rhythm (Lüning and Tom Dieck 1989; Lüning and Kadel 1993). Experiments have indicated that the development of the endogenous growth rhythm of juvenile Laminaria sporophytes occurred a few weeks after sporophyte ontogeny (Bartsch et al. 2008), possibly explaining the longer growth season for juvenile sporophytes, as well as the higher DGR of the younger April outplanting sporophytes in the present study. DGR declined significantly over the duration of both the February and April outplantings. Growth reduction for S. japonica has been shown to occur when QN falls below 21 mg g−1 DW (Mizuta et al. 1997). In our study, this value was reached around mid-June, approximately the same time when the C:N sharply increased. This growth pattern, with the main growth occurring during winter and carbon being stored during summer, is consistent with other studies in areas with nitrogen abundant in winter (Gagné et al. 1982).

Both later outplanting and season significantly increased the shedding of the tips (DSR). A higher amount of shedding of S. latissima has been positively correlated to E-DIN (Boderskov et al. 2016), whereas the opposite has been the case for U. pinnatifida (Yoshikawa et al. 2001). Our study does not support an effect of E-DIN on shedding rates. Frond age of several Laminariales has a positive correlation with shedding (Kurogi 1957; Nishikawa 1967; Zhang et al. 2012). However, Sjøtun (1993) found that shedding per se is not related to age, but that longer fronds are more prone to shedding. This is not consistent with our results of a relatively higher shedding of the smaller individuals in the April outplanting.

Epibiosis (total, species and M. membranacea settlers)

Our results supported the hypothesis that outplanting time affects the amount of fouling organisms (epizoans) in general and M. membranacea settlers in particular. In September, when fouling was greatest, the occurrence of epizoans was significantly higher in the seaweed outplanted earliest than at the later outplanting times. Epibiosis of perennial seaweeds at mid- and high latitudes typically peaks earlier than in our study, in summer, when seaweed growth rate is reduced (Lüning and Pang 2003) and recruitment rates of epizoic larvae increase (Lüning and Pang 2003; Saunders and Metaxas 2007; Forbord et al. 2020). Increasing temperature is the main driver for the timing of larval settlement (Saunders and Metaxas 2007). Continuous growth and shedding in summer, which was higher for the April outplanting, may help reduce the density of fouling organisms. The differences in epizoan densities among the outplanting times may, therefore, be a result of the relationship between larval supply timing and different turnover times of frond tissue caused by the varying growth and shedding rate. From an industrial point of view, however, it is more important to note that seaweed from both successful outplanting dates were in fact greatly fouled by September regardless of outplanting date (>550 epizoans m−2 frond for February experiment and > 300 epizoans m−2 frond for April experiment). The seaweed outplanted in May was much less fouled (<60 epizoans m−2 frond), but the biomass produced was minimal.

The two most abundant epizoans, the bryozoan M. membranacea and the hydroid O. geniculata, were also reported as dominant taxa in earlier studies in this region (Matsson et al. 2019; Forbord et al. 2020). Both species are widespread and found on cultivated (Peteiro and Freire 2013; Førde et al. 2015; Walls et al. 2017) and wild seaweed in the boreal and sub-Arctic Atlantic (Lambert 1990; Fredriksen et al. 2005; Scheibling and Gagnon 2009). The other three less abundant species in this study, Electra pilosa, Mytilus edulis and Balanus sp., are not reported by the same studies, likely because of their low density on cultivated seaweed (Matsson et al. 2019; Forbord et al. 2020). Density of M. membranacea settlers was higher on seaweed outplanted in February compared to April and May. This is the first study showing that M. membranacea settlers prefer S. latissima fronds that are outplanted later in the season. It was also shown that the younger meristematic regions had a higher density of M. membranacea settlers, in agreement with previous studies and possibly as a result of preferential larval settlement (Denley et al. 2014). In addition, M. membranacea larvae may alter their behaviour in response to habitat types and can detect small-scale differences in substrate quality (Matson et al. 2010), possibly through chemical cues (Brumbaugh et al. 1994). In the present study, there were no significant differences between the concentrations of N-compounds (I-DIN and QN) within the seaweed tissue of the different outplanting times, making a nitrogen cue unlikely. Production of defence compounds such as phlorotannins may provide an alternative cue. Pavia and Toth (2000) suggest a Carbon Nutrient Balance Model for seaweeds, according to which photosynthetically fixed carbon will be allocated to production of defence compounds when nutrients are limiting growth (i.e. when C:N is high). While we did not measure defence compounds, the C:N ratio was significantly higher in seaweed outplanted in April than February, particularly in mid-August prior to the peak in epibiosis, implying a possible higher production of defence compounds in the April outplanting.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that, for the February outplanting, a prolonged time for grow-out at sea prior to the main recruitment event in September resulted in a doubled frond area than in the April outplanting. Therefore, we recommend outplanting in February over April in this area. Even earlier outplanting before the onset of the Polar night in late autumn may be advantageous and should be examined although it poses a higher risk of autumn and winter storms damaging the seaweed farm. Outplanting time affected the quantity of seaweed produced, and from an industrial perspective, outplanting time also affected the quality of the produced biomass. An earlier outplanting time resulted in lower carbon content and higher amount of fouling epizoans, but no difference in seaweed nitrogen compounds (I-DIN or QN). The most suitable harvesting time, therefore, depends on the type of desired end-product. When large biomass production is preferred, an extended grow-out phase with latest harvesting is recommended. For more delicate fronds with little epibiosis intended for direct human consumption, a delayed outplanting and earlier harvesting may be advantageous. Depending on the desired chemical composition when producing feed ingredients or to produce microbial growth media, protein-rich epizoans may be included in the end-product, allowing for a later harvesting. In conclusion, our findings improve the knowledge on optimal cultivation period as well as the effect of variation in cultivation timing, thereby improving the yield as well as the quality of cultivated seaweed.

References

Asare SO, Harlin MM (1983) Seasnal fluctuations in tissue nitrogen for five species of perennial macroalgae in Rhode Island sound. J Phycol 19:254–257

Azevedo IC, Duarte PM, Marinho GS, Neumann F, Sousa-Pinto I (2019) Growth of Saccharina latissima (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) cultivated offshore under exposed conditions. Phycologia 58:504–515

Bak UG, Mols-Mortensen A, Gregersen O (2018) Production method and cost of commercial-scale offshore cultivation of kelp in the Faroe Islands using multiple partial harvesting. Algal Res 33:36–47

Bartsch I, Wiencke C, Bischof K, Buchholz CM, Buck BH, Eggert A, Feuerpfeil P, Hanelt D, Jacobsen S, Karez R (2008) The genus Laminaria sensu lato: recent insights and developments. Eur J Phycol 43:1–86

Black W (1950) The seasonal variation in weight and chemical composition of the common British Laminariaceae. J Mar Biol Assoc U K 29:45–72

Boderskov T, Schmedes PS, Bruhn A, Rasmussen MB, Nielsen MM, Pedersen MF (2016) The effect of light and nutrient availability on growth, nitrogen, and pigment contents of Saccharina latissima (Phaeophyceae) grown in outdoor tanks, under natural variation of sunlight and temperature, during autumn and early winter in Denmark. J Appl Phycol 28:1153–1165

Broch OJ, Ellingsen IH, Forbord S, Wang X, Volent Z, Alver MO, Handå A, Andresen K, Slagstad D, Reitan KI (2013) Modelling the cultivation and bioremediation potential of the kelp Saccharina latissima in close proximity to an exposed salmon farm in Norway. Aquacult Environ Interact 4:187–206

Broch OJ, Alver MO, Bekkby T, Gundersen H, Forbord S, Handå A, Skjermo J, Hancke K (2019) The kelp cultivation potential in coastal and offshore regions of Norway. Front Mar Sci 5:529

Bruhn A, Tørring DB, Thomsen M, Canal-Vergés P, Nielsen MM, Rasmussen MB, Eybye KL, Larsen MM, Balsby TJS, Petersen JK (2016) Impact of environmental conditions on biomass yield, quality, and bio-mitigation capacity of Saccharina latissima. Aquacult Environ Interact 8:619–636

Brumbaugh DR, West JM, Hintz JL, Anderson F (1994) Determinants of recruitment by an epiphytic marine bryozoan: field manipulations of flow and host quality. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Buck BH, Nevejan N, Wille M, Chambers MD, Chopin T (2017) Offshore and multi-use aquaculture with extractive species: seaweeds and bivalves. In: Buck BH, Langan R (eds) Aquaculture perspective of multi-use sites in the open ocean. Springer, Cham, pp 23–69

Chapman A, Craigie J (1977) Seasonal growth in Laminaria longicruris: relations with dissolved inorganic nutrients and internal reserves of nitrogen. Mar Biol 40:197–205

Chapman A, Markham J, Lüning K (1978) Effects of nitrate concentration on the growth and physiology of Laminaria saccharina (Phaeophyta) in culture. J Phycol 14:195–198

Chopin T (2014) Seaweeds: Top Mariculture Crop, Ecosystem Service Provider. Glob Aquacult Advocate 17:54–56

Creed JC, Kain JM, Norton TA (1998) An experimental evaluation of density and plant size in two large brown seaweeds. J Phycol 34:39–52

Custódio M, Villasante S, Calado R, Lillebø AI (2020) Valuation of ecosystem services to promote sustainable aquaculture practices. Rev Aquac 12:392–405

Denley D, Metaxas A, Short J (2014) Selective settlement by larvae of Membranipora membranacea and Electra pilosa (Ectoprocta) along kelp blades in Nova Scotia, Canada. Aquat Biol 21:47–56

Druehl LD, Cabot EL, Lloyd KE (1987) Seasonal growth of Laminaria groenlandica as a function of plant age. Can J Bot 65:1599–1604

Druehl LD, Baird R, Lindwall A, Lloyd KE, Pakula S (1988) Longline cultivation of some Laminariaceae in British Columbia, Canada. Aquac Fish Manag 19:253–263

Edwards M, Watson L (2011) Aquaculture Explained: no. 26, Cultivating Laminaria digitata. Irish Sea Fisheries Board: Dunlaoghaire, Ireland

FAO (2020) The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. Sustainability in Action. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

FAO (2018) Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. FAO Rome. http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/global-aquaculture-production/query/en. Accessed 2 Sept 2020

Forbord S, Skjermo J, Arff J, Handå A, Reitan KI, Bjerregaard R, Lüning K (2012) Development of Saccharina latissima (Phaeophyceae) kelp hatcheries with year-round production of zoospores and juvenile sporophytes on culture ropes for kelp aquaculture. J Appl Phycol 24:393–399

Forbord S, Steinhovden KB, Rød KK, Handå A, Skjermo J (2018) Cultivation protocol for Saccharina latissima. In: Charrier B, Wichard T, Reddy CRK (eds) Protocols for Macroalgae Research. CRC Press, Boca Raton pp 37–59

Forbord S, Matsson S, Brodahl GE, Bluhm BA, Broch OJ, Handå A, Metaxas A, Skjermo J, Steinhovden KB, Olsen Y (2020) Latitudinal, seasonal and depth-dependent variation in growth, chemical composition and biofouling of cultivated Saccharina latissima (Phaeophyceae) along the Norwegian coast. J Appl Phycol 32:2215–2232

Forbord S, Etter SA, Broch OJ, Dahlen VR, Olsen Y (2021) Initial short-term nitrate uptake in juvenile, cultivated Saccharina latissima (Phaeophyceae) of variable nutritional state. Aquat Bot 103306

Førde H, Forbord S, Handå A, Fossberg J, Arff J, Johnsen G, Reitan KI (2015) Development of bryozoan fouling on cultivated kelp (Saccharina latissima) in Norway. J Appl Phycol 28:1225–1234

Fortes MD, Lüning K (1980) Growth rates of North Sea macroalgae in relation to temperature, irradiance and photoperiod. Helgol Meeresunters 34:15–29

Fredriksen S, Christie H, Andre Sæthre B (2005) Species richness in macroalgae and macrofauna assemblages on Fucus serratus L. (Phaeophyceae) and Zostera marina L. (Angiospermae) in Skagerrak, Norway. Mar Biol Res 1:2–19

Gagné J, Mann K, Chapman A (1982) Seasonal patterns of growth and storage in Laminaria longicruris in relation to differing patterns of availability of nitrogen in the water. Mar Biol 69:91–101

García-Poza S, Leandro A, Cotas C, Cotas J, Marques JC, Pereira L, Gonçalves AM (2020) The evolution road of seaweed aquaculture: cultivation technologies and the industry 4.0. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:6528

Handå A, Forbord S, Wang X, Broch OJ, Dahle SW, Størseth TR, Reitan KI, Olsen Y, Skjermo J (2013) Seasonal-and depth-dependent growth of cultivated kelp (Saccharina latissima) in close proximity to salmon (Salmo salar) aquaculture in Norway. Aquaculture 414:191–201

Hanisak MD (1983) The nitrogen relationships of marine macroalgae. In: Carpenter EJ, Capone DG (eds) Nitrogen in the Marine Environment. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 699–730

Hepburn CD, Hurd CL, Frew RD (2006) Colony structure and seasonal differences in light and nitrogen modify the impact of sessile epifauna on the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera (L.) C Agardh. Hydrobiologia 560:373–384

Hurd CL, Harrison PJ, Bischof K, Lobban CS (2014) Seaweed ecology and physiology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ibrahim A, Olsen A, Lauvset S, Rey F (2014) Seasonal variations of the surface nutrients and hydrography in the Norwegian Sea. Int J Environ Sci Dev 5:496–505

Jaccard J, Jaccard J (1998) Interaction effects in factorial analysis of variance. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Jiang Z, Liu J, Li S, Chen Y, Du P, Zhu Y, Liao Y, Chen Q, Shou L, Yan X (2020) Kelp cultivation effectively improves water quality and regulates phytoplankton community in a turbid, highly eutrophic bay. Sci Total Environ 707:135561

Kain J, Dawes C (1987) Useful European seaweeds: past hopes and present cultivation. Hydrobiologia 151:173–181

Kain J, Holt T, Dawes C (1990) European Laminariales and their cultivation. In: Yarish C, Penniman CA, Van Petten P (eds) Economically Important Marine Plants of the Atlantic: Their Biology and Cultivation. Connecticut Sea Grant College Program, Groton, pp 95–111

Krumhansl KA, Lee JM, Scheibling RE (2011) Grazing damage and encrustation by an invasive bryozoan reduce the ability of kelps to withstand breakage by waves. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 407:12–18

Kurogi M (1957) Studies of ecology and culture of Undaria pinnatifida (Sur.) Hariot. Bull Tohoku Reg Fish Res Lab 10:95–117

Lambert WJ (1990) Population ecology and feeding biology of nudibranchs in colonies of the hydroid Obelia geniculata. PhD dissertation, University New Hampshire, Durham

Littler MM, Arnold KE (1982) Primary productivity of marine macroalgal fuctional-form groups from southwest North America. J Phycol 18:307–311

Long MH, Rheuban JE, Berg P, Zieman JC (2012) A comparison and correction of light intensity loggers to photosynthetically active radiation sensors. Limnol Oceanogr Methods 10:416–424

Lubsch A, Timmermans KR (2019) Uptake kinetics and storage capacity of dissolved inorganic phosphorus and corresponding dissolved inorganic nitrate uptake in Saccharina latissima and Laminaria digitata (Phaeophyceae). J Phycol 55:637–650

Lüning K (1979) Growth strategies of three Laminaria species (Phaeophyceae) inhabiting different depth zones in the sublittoral region of Helgoland (North Sea). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1:195e207

Lüning K, Kadel P (1993) Daylength range for circannual rhythmicity in Pterygophora californica (Alariaceae, Phaeophyta) and synchronization of seasonal growth by daylength cycles in several other brown algae. Phycologia 32:379–387

Lüning K, Pang S (2003) Mass cultivation of seaweeds: current aspects and approaches. J Appl Phycol 15:115–119

Lüning K, Tom Dieck I (1989) Environmental triggers in algal seasonality. Bot Mar 32:389–397

Mann K (1973) Seaweeds: their productivity and strategy for growth. Science 182:975–981

Marinho GS, Holdt SL, Angelidaki I (2015) Seasonal variations in the amino acid profile and protein nutritional value of Saccharina latissima cultivated in a commercial IMTA system. J Appl Phycol 27:1991–2000

Matson PG, Steffen BT, Allen RM (2010) Settlement behavior of cyphonautes larvae of the bryozoan Membranipora membranacea in response to two algal substrata. Invertebr Biol 129:277–283

Matsson S, Christie H, Fieler R (2019) Variation in biomass and biofouling of kelp, Saccharina latissima, cultivated in the Arctic, Norway. Aquaculture 506:445–452

Maxwell SE, Delaney HD, Kelley K (2017) Designing experiments and analyzing data: a model comparison perspective. Routledge, London

Mizuta H, Torii K, Yamamoto H (1997) The relationship between nitrogen and carbon contents in the sporophytes of Laminaria japonica (Phaeophyceae). Fish Sci 63:553–556

Mortensen LM (2017) Remediation of nutrient-rich, brackish fjord water through production of protein-rich kelp S. latissima and L. digitata. J Appl Phycol 29:3089–3096

Nishikawa H (1967) Studies on the cultivation of Undaria pinnatifida: IV. Focused on growth and erosion (a prediction). Aquaculture 14:197–203

Parke M (1948) Studies on British Laminariaceae. I. Growth in Laminaria saccharina (L.) Lamour. J Mar Biol Assoc U K 27:651–709

Pavia H, Toth GB (2000) Influence of light and nitrogen on the phlorotannin content of the brown seaweeds Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus. Hydrobiologia 440:299–305

Peteiro C, Freire Ó (2009) Effect of outplanting time on commercial cultivation of kelp Laminaria saccharina at the southern limit in the Atlantic coast, NW Spain. Chin J Oceanol Limnol 27:54–60

Peteiro C, Freire Ó (2012) Outplanting time and methodologies related to mariculture of the edible kelp Undaria pinnatifida in the Atlantic coast of Spain. J Appl Phycol 24:1361–1372

Peteiro C, Freire Ó (2013) Epiphytism on blades of the edible kelps Undaria pinnatifida and Saccharina latissima farmed under different abiotic conditions. J World Aquacult Soc 44:706–715

Queen JP, Quinn GP, Keough MJ (2002) Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

R Core Team (2018) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Randelhoff A, Reigstad M, Chierici M, Sundfjord A, Ivanov V, Cape M, Vernet M, Tremblay J-É, Bratbak G, Kristiansen S (2018) Seasonality of the physical and biogeochemical hydrography in the inflow to the Arctic Ocean through Fram Strait. Front Mar Sci 5:224

Rød KK (2012) Sori disinfection in cultivation of Saccharina latissima: Evaluation of chemical treatments against diatom contamination. Masters Thesis, Institute for Biology, NTNU,

Roleda MY, Hurd CL (2019) Seaweed nutrient physiology: application of concepts to aquaculture and bioremediation. Phycologia 58:552–562

RStudio Team (2016) RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA

Saunders M, Metaxas A (2007) Temperature explains settlement patterns of the introduced bryozoan Membranipora membranacea in Nova Scotia, Canada. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 344:95–106

Saunders M, Metaxas A (2009) Population dynamics of a nonindigenous epiphytic bryozoan Membranipora membranacea in the western North Atlantic: effects of kelp substrate. Aquat Biol 8:83–94

Scheibling RE, Gagnon P (2009) Temperature-mediated outbreak dynamics of the invasive bryozoan Membranipora membranacea in Nova Scotian kelp beds. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 390:1–13

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675

Sharma S, Neves L, Funderud J, Mydland LT, Øverland M, Horn SJ (2018) Seasonal and depth variations in the chemical composition of cultivated Saccharina latissima. Algal Res 32:107–112

Sjøtun K (1993) Seasonal lamina growth in two age groups of Laminaria saccharina (L.) Lamour. in western Norway. Bot Mar 36:433–442

Sjøtun K, Fredriksen S, Rueness J (1996) Seasonal growth and carbon and nitrogen content in canopy and first-year plants of Laminaria hyperborea (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae). Phycologia 35:1–8

Skjermo J, Aasen IM, Arff J, Broch OJ, Carvajal A, Christie H, Forbord S, Olsen Y, Reitan KI, Rustad T (2014) A new Norwegian bioeconomy based on cultivation and processing of seaweeds: Opportunities and R&D needs. SINTEF Report A 25981.46 pp

Stévant P, Marfaing H, Rustad T, Sandbakken I, Fleurence J, Chapman A (2017) Nutritional value of the kelps Alaria esculenta and Saccharina latissima and effects of short-term storage on biomass quality. J Appl Phycol 29:2417–2426

Svensson C, Pavia H, Toth G (2007) Do plant density, nutrient availability, and herbivore grazing interact to affect phlorotannin plasticity in the brown seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum. Mar Biol 151:2177–2181

Tseng, C. K., Sun, K. Y., & Wu, C. Y. (1955). On the cultivation of Haidai (Laminaria japonica Aresch.) by summering young sporophytes at low temperature. J Integr Plant Biol 4(3):255-264 (In Chinese with English summary)

Tseng CK (2001) Algal biotechnology industries and research activities in China. J Appl Phycol 13:375–380

Tseng CK (2004) The past, present and future of phycology in China. Hydrobiologia 512:11–20

Visch W, Kononets M, Hall PO, Nylund GM, Pavia H (2020a) Environmental impact of kelp (Saccharina latissima) aquaculture. Mar Pollut Bull 155:110962

Visch W, Nylund GM, Pavia H (2020b) Growth and biofouling in kelp aquaculture (Saccharina latissima): the effect of location and wave exposure. J Appl Phycol 32:3199–3209

Wahl M (1989) Marine epibiosis. I. Fouling and antifouling: some basic aspects. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 58:175–189

Walls A, Edwards M, Firth L, Johnson M (2017) Successional changes of epibiont fouling communities of the cultivated kelp Alaria esculenta: predictability and influences. Aquacult Environ Interact 9:55–69

Wheeler PA, North WJ (1980) Effect of nitrogen supply on nitrogen content and growth rate of juvenile Macrocystis pyrifiera (Phaeophyta) sporophytes. J Phycol 16:577–582

Wheeler P, North W (1981) Nitrogen supply, tissue composition and frond growth rates for Macrocystis pyrifera off the coast of southern California. Mar Biol 64:59–69

Yorke AF, Metaxas A (2012) Relative importance of kelps and fucoids as substrata of the invasive epiphytic bryozoan Membranipora membranacea in Nova Scotia, Canada. Aquat Biol 16:17–30

Yoshikawa T, Takeuchi I, Furuya K (2001) Active erosion of Undaria pinnatifida Suringar (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) mass-cultured in Otsuchi Bay in northeastern Japan. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 266:51–65

Zhang J, Fang J, Wang W, Du M, Gao Y, Zhang M (2012) Growth and loss of mariculture kelp Saccharina japonica in Sungo Bay, China. J Appl Phycol 24:1209–1216

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway (incl University Hospital of North Norway). We would like to thank Paul Dubourg (UiT) for conducting the CN analysis, Zsolt Volent and Magnus Oshaug Pedersen (SINTEF Ocean) for operating the Hobo-loggers, Hartvig Christie (NIVA) for scientific discussion of the MS content, Ekaterina Storhaug (Akvaplan-Niva) for providing the map (figure 1), Magnus Aune for guidance with Rstudio, and Ole-Jacob Broch (SINTEF Ocean) for mathematical guidance with growth and shedding rates. We would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for valuable inputs, improving the quality of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Research Council of Norway, project no. 254883 (MacroSea). The seeding production was carried out within the framework of the research infrastructure Norwegian Center for Plankton Technology (245937/F50).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 1061 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsson, S., Metaxas, A., Forbord, S. et al. Effects of outplanting time on growth, shedding and quality of Saccharina latissima (Phaeophyceae) in its northern distribution range. J Appl Phycol 33, 2415–2431 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-021-02441-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-021-02441-z