Abstract

Covid-19 and its lockdown measures have uniquely challenged people’s wellbeing and numerous studies have been carried out to understand the effects of such lockdown measures on mental health. Yet, to date most of these studies do not assess psychological pathways and conditional effects. By drawing on self-determination theory, the present study tested whether the relationship between lockdown loneliness and mental health is mediated via basic needs satisfaction (relatedness, autonomy, and competence) and whether these associations are exacerbated for younger age groups. A total of 339 Portuguese residents completed an anonymous web-based survey during the Covid-19 lockdown in March 2021. The results corroborate a significant link between perceived loneliness and anxiety as well as depression. Parallel mediation analyses showed that competence consistently mediated the lockdown loneliness-mental health link. Moderated mediated analyses also confirmed that the psychosocial pathway applied most strongly to younger age groups. These findings highlight the role of social factors for competence need satisfaction and mental health among younger people during the Covid-19 lockdown in Portugal. The results also point to potential avenues for future prevention measures to mitigate the harmful effects that social exclusion can bring about.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Covid-19 Lockdown Loneliness and Mental Health

The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction and the Moderating Role of Age

The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in numerous government interventions, of which the most restrictive were lockdowns which consist of social restriction measures such as stay-at-home orders, curfews, quarantines which uniquely affected the wellbeing of the entire population, leading to a staggering increase in mental health problems (e.g., Paulino et al., 2021). Because lockdown measures significantly limited opportunities for social interaction, loneliness and related mental health problems were of particular concern as evidenced by some studies (Ernst et al., 2022; González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Sousa et al., 2021). And there is some indication that young adults might have been particularly affected by the social restriction measures during the pandemic (e.g., Weissbourd et al., 2020).

While many studies have been carried out to understand the effects of Covid-19 lockdown measures on mental health (Costa et al., 2022; Dimmock et al., 2021), most studies have not yet assessed socio-psychological pathways and conditional effects. This is an important research gap that limits the development of targeted prevention and interventions that could mitigate the harmful effects of loneliness perceptions within and outside the Covid-19 context. Appropriate interventions to address loneliness are very important and can have a lasting impact on mental health. Therefore, this study aims to add to the Covid-19 mental health literature by identifying relevant mediating and moderating variables to better understand the link between loneliness and mental health during the lockdown. More specifically, this study investigates whether perceived challenges to basic psychological needs satisfaction for relatedness, autonomy, and competence during the second hard lockdown in Portugal in March 2021 are part of the socio-psychological process explaining mental health issues and whether this process is exacerbated among younger people.

Lockdown Loneliness and Mental Health

Lockdown measures significantly reduced the possibility to connect with colleagues, friends and relatives and there is cumulative evidence for an increased prevalence of perceived loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g., Buecker & Horstmann, 2021; Kovacs et al., 2021). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis, which included 19 longitudinal studies comparing perceived loneliness during the lockdown to pre Covid-19 loneliness levels, found that feelings of loneliness significantly increased during the pandemic (with a standardized Mean Difference = 0.27 [0.14–0.40] for continuous measurements; Ernst et al., 2022). Even though, this is considered a small effect (Cohen, 1992; Ferguson, 2009), the finding of a modest increase in loneliness during the pandemic is underpinned by several compelling factors. As Ernst and colleagues (2022) pointed out these include the robust results of sensitivity analyses, the rigorous selection of high-quality and longitudinal research for the meta-analyses, the substantial number of studies encompassing a pooled sample of over 45,000 participants, and the absence of any signs of publication bias. These collective elements reinforce the assertion that there has indeed been a genuine rise in loneliness, even if it was relatively small in magnitude.

Moreover, there is cumulative evidence that perceived loneliness is related to adverse mental health outcomes, such as anxiety and depression, in general (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Jackson & Cochran, 1991; Park et al., 2020) and during the Covid-19 pandemic in particular (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Gozansky et al., 2021; Killgore et al., 2020). One of the few longitudinal studies that examined individuals´ mental health in the Portuguese context by comparing pre- and post-pandemic mental health data also demonstrated that Covid-19 lockdown measures were associated with an increase in depressive symptoms, and a decrease in quality of life, which were linked to loneliness. Furthermore, the study revealed that perceived loneliness during the lockdown was significantly correlated with increased anxiety-related symptoms (Nogueira et al., 2021). We therefore expected that:

- H1:

-

Perceived loneliness is related to adverse mental health outcomes.

Basic Need Satisfaction as Mediators

Self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 2000) assumes that people universally strive to satisfy their basic psychological needs for relatedness (the feeling of having meaningful connections to other people and the ability to develop interpersonal relationships), autonomy (the ability to act and choose freely the things one wants to do), and competence (the ability to act effectively with one’s environment and accomplish difficult tasks). These needs that are critical to human psychological functioning and wellbeing in a variety of contexts (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Basic psychological need satisfaction is related to the intrinsic motivation for integration into the social sphere. Hence, meaningful social interactions are an important component for need satisfaction (La Guardia et al., 2000). The proponents of SDT assert that changes in the social context can affect the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (La Guardia et al., 2000; La Guardia & Patrick, 2008; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Accordingly, the social environment can either hinder or facilitate their satisfaction and thus determine whether optimal psychological functioning and wellbeing are accomplished (La Guardia et al., 2000; La Guardia & Patrick, 2008; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). There is little empirical evidence on the link between perceived loneliness and basic need satisfaction during the pandemic. However, a recent study from Italy including 1,344 participants assessed basic need satisfaction before, during and after one month of lockdown in Italy and found a significant decrease of need satisfaction during and after the lockdown (Costa et al., 2022). Furthermore, the study evaluated the longitudinal link between on- and offline social support, basic need satisfaction and anxiety. The results demonstrated that both on- and offline social support were linked to increased satisfaction of all three basic psychological needs leading to reduced anxiety (Costa et al., 2022). Hence, building on SDT and the empirical evidence on the importance of social interactions and support for basic need satisfaction we expected that perceived loneliness is related to need dissatisfaction.

There is also a growing body of research showing that basic need satisfaction is a precondition for good mental health in the Covid-19 context (e.g., Cantarero et al., 2021; Schutte & Malouff, 2021; Vermote et al., 2022). For instance, Levine et al. (2022) used a cross-lagged-panel design to assess the relation between basic needs, negative affect, and depression in a Canadian sample (N = 379 students). Results demonstrated that basic need dissatisfaction was a robust indicator for negative affect and depression over a one-year period (Levine et al., 2022) and similar results have been found in a longitudinal study with 835 Belgian participants. Moreover, a large study from Germany (N = 1,086) examined the impact of reduced need satisfaction for autonomy and relatedness on mental health in the general population. The results showed that autonomy dissatisfaction in particular was associated with increased anxiety and depression (Schwinger et al., 2020).

Taken together, the evidence strongly suggests that perceived loneliness is related to the dissatisfaction of basic psychological needs which in turn is associated with adverse mental health outcomes. Hence, we hypothesized that:

- H2:

-

Basic psychological need satisfaction mediates the relationship between perceived loneliness and mental health.

The Moderating Role of Age

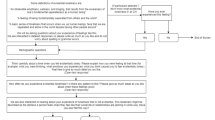

While theorists suggest that basic need satisfaction is essential for human wellbeing and functioning in all life stages, it is conceivable that developmental changes covary with the importance of need satisfaction to ensure wellbeing (Ryan & La Guardia, 2000). In his psychosocial theory of development, Erikson (1968) proposes that human life span development comprises different developmental stages in which each stage is characterized by certain development tasks and crises (Erikson, 1968). Emerging adulthood (i.e., age range between 18 and 29; Arnett, 2004) is characterized by particular social challenges, i.e. the crisis of intimacy, which means that individuals are concerned about the pursuit of intimate connections with others. Overcoming this crisis leads to successful connectedness, whereas avoiding it can lead to a sense of loneliness. Hence, the psychological wellbeing of emerging adults depends in particular on successfully mastering these crises (Erikson, 1968). Other life span development theorists also suggested that emerging adults are particularly focused on the development of social connections and intimate relationships (e.g., Arnett, 2000). Accordingly, we suggest that the association between perceived loneliness and basic need dissatisfaction is especially strong for emerging adults, as social connections are crucial for young people’s satisfaction of basic psychological needs (see Fig. 1).

Additionally, emerging adults are in a developmental phase in which they are particularly vulnerable to develop mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Patten, 2017). A large research body confirms that emerging adults have been particularly affected by the experience of perceived loneliness, anxiety and depression during the Covid-19 pandemic (Ausín et al., 2022; Carson et al., 2020; Groarke et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020;), and that young age exacerbates the loneliness-anxiety link (McDonald et al., 2022).

Research has also shown that basic need satisfaction is strongly related to mental health and wellbeing for young people (Emery et al., 2015; Eryilmaz, 2012; Tian et al., 2014). Moreover, a recent study from the first lockdown in Portugal (in April 2020) suggests that age could be a potential moderator in the link between basic need satisfaction and mental health (Antunes et al., 2020), albeit it was not directly tested. In the current study, we are particularly interested in the third pandemic wave in March of 2021 as it was characterized by high infection rates and high compliance of the Portuguese population in regard to social restriction measures (Pinho et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2022; Torres et al., 2022).

Hence, we hypothesized:

- H3:

-

Age moderates the direct and indirect relations between perceived loneliness and mental health in such a way that young age exacerbates these links.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The study was approved by the university´s ethical committee (Nr. 75/2021) and all participants were provided with informed consent.

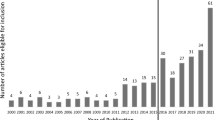

Data were collected via convenience and snowball sampling and included 387 participants who answered an anonymous Qualtrics survey from March 24th to April 12th, 2021. Participants had to be (1) at least 18 years old and (2) residents in Portugal during the second hard lockdown period in March 2021, to take part in this study. A total of 12 participants did not meet these inclusion criteria and 48 participants were excluded as they did not respond to any of the scales included in this analysis resulting in a final sample of 339 participants.

Most of the participants were PortugueseFootnote 1 (79%, n = 266). The participants age ranged from 18 to 73 years with a mean age of 28 (SD = 11.87, Mdn = 22.00). A bit more than half of the sample (63%) indicated to be female. Regarding occupational status, 42% (n = 141) were students, 24% (n = 80) were workers, 7% (n = 23) were working and studying simultaneously, 6% (n = 19) reported that they were unemployed, while 2% (n = 6) were in lay-off and 1% (n = 4) were retired. A total of 19% (n = 66) of the sample did not report their occupational status.

Measures

Unless indicated differently, all measures included a frame of reference to the last month or to the pandemic.

The validated Portuguese version of the The UCLA Loneliness Scale (UCLA; Pocinho et al., 2010) was used consisting of nine Likert-scales items (ranging from 0 = I have never felt this way to 3 = I have frequently felt that way; α = 0.89).

The Portuguese version of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS; Sousa et al., 2012) was used to assess the satisfaction of basic psychological needs which comprises 12 items. Responses were given on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = completely false to 5 = completely true). The items assess three subscales of need satisfaction regarding (1) relatedness (four items), (2) autonomy (four items) and (3) competence (four items). All items related to need frustration were removed because frustration of needs is a matter of actively blocking the satisfaction of needs. However, in the pandemic, needs were not actively blocked, but the context did not allow for the needs to be satisfied. Moreover, the item “I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake” was removed from the autonomy subscale as it demonstrated poor internal consistency (α = 0.57). After removing the item, the internal consistency for the subscales in this study ranged from acceptable to good (relatedness α = 0.82; autonomy α = 0.67; and competence α = 0.84).

The Portuguese version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale was used to assess anxiety (7 items; α = 0.86) and depression (7 items; α = 0.91) symptoms during the lockdown (Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004). Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = did not apply to me to 3 = applied to me most of the time).

Research suggests that experiences of the lockdown have been worse for women (Antunes et al., 2020). Additionally, general subjective wellbeing has been found to negatively correlate with anxiety, and depression (Gargiulo & Stokes, 2009). Thus, we included (1) gender as well as a composite measure of (2) general subjective wellbeing consisting of two items (general happiness and general satisfaction with life; 0 = extremely unhappy/unsatisfied to 5 = extremely happy/satisfied) as covariates in all our analysis.

Results

A summary of descriptive statistics and correlations for the main study variables is provided in Table 1. We used SPSS PROCESS macro (version 4.0) by Hayes (2013) and model 4 to test H1 and H2 and model 59 to test H3.

To test hypothesis 1 and 2, we entered general subjective wellbeing and gender as covariates in all our analysis. However, gender was consistently a non-significant covariate. Thus, we re-ran all models where we only entered subjective wellbeing as a covariate.

We first examined the total effect in the mediation model and found that perceived loneliness was significantly related to anxiety (B = 0.420, SE = 0.047, 95% CI [0.327, 0.513]) and depression (B = 0.573, SE = 0.049, 95% CI [0.477, 0.668]) therefore supporting our first hypothesis (see Table 2). We then tested the mediation hypothesis by entering all three mediators (autonomy, competence, relatedness) simultaneously, but calculating two separate mediation models - one for each of the mental health outcomes (anxiety and depression).

Perceived loneliness was positively and significantly related to anxiety (B = 0.390, t = 8.108, p < .001), and depression (B = 0.498, t = 10.704, p < .001). Perceived loneliness also had a negative and significant effect on all three basic needs: Relatedness (B = − 0.390, t = -6.930, p < .001), autonomy (B = − 0.190, t = -3.080, p = .002), and competence (B = − 0.227, t = − 3.517, p = .001). In turn, competence predicted significantly and negatively both anxiety (B = − 0.319, SE = 0.054, 95% CI [− 0.424, − 0.213]) and depression (B = − 0.096, SE = 0.029, 95% CI [− 0.153, − 0.038]) while relatedness and autonomy did not have a significant effect on either mental health outcome.

Furthermore, as can be seen in Table 2, there was a significant indirect effect of perceived loneliness on anxiety (B = 0.072, SE = 0.026, 95% CI [0.026, 0.127]) and depressive symptoms (B = 0.066, SE = 0.022, 95% CI [0.025, 0.114]) via need for competence satisfaction. Yet, relatedness satisfaction did not significantly mediate the relationship between perceived loneliness and mental health. Other significant indirect effects only emerged in the case of autonomy mediating perceived loneliness and depressive symptoms (B = 0.022, SE = 0.013, 95% CI [0.001, 0.052]) but not anxiety (see Table 2).

We also expected participant age to be a boundary condition for the psychosocial pathway linking perceived loneliness during lockdown to mental health (H3). Table 3 demonstrates the results for the moderated mediation. The conditional direct and indirect effects were evaluated at the 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles of age. Age did not significantly moderate the link between perceived loneliness and mental health outcomes indicating that participants who felt lonely also felt more anxious and depressed and this was independent of age. Hence, the direct effect was not significantly moderated by age. Yet, the results also suggested that the link between perceived loneliness and competence satisfaction was significantly moderated by age (B = 0.011, SE = 0.005, 95% CI [0.001, 0.022]). A plot of this interaction effect is shown in Fig. 2.

We further probed into this moderated mediation by conducting a simple slope analysis, which demonstrated that the effect of loneliness on competence was significantly negative for the 16th percentile (B = − 0.249, SE = 0.074, p = .001, 95% CI [-0.394, − 0.104]) and 50th percentile (B = − 0.228, SE = 0.069, p = .001, 95% CI [-0.364, − 0.092]). Yet, for middle-aged participants, there was no significant link between perceived loneliness and competence (B = − 0.039, SE = 0.094, p = .679, 95% CI [-0.223, 0.146]). When using the Johnson-Neyman-technique we found that the effect of perceived loneliness on competence was significant and negative for participants below the age of 32Footnote 2 (n = 61; 22% of the sample).

The results of the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap further corroborated that the indirect effect of competence on the relation between perceived loneliness and anxiety was significant only at the 16th percentileFootnote 3 (B = 0.073, SE = 0.030, 95% CI [0.023, 0.139] and 50th percentile of age (B = 0.065, SE = 0.026, 95% CI [0.019, 0.123] but not the 84th percentile of age (B = 0.008, SE = 0.017, 95% CI [-0.025, 0.044]. This was also confirmed for the indirect effect on depression (16th percentile: B = 0.068, SE = 0.028, 95% CI [0.022, 0.129]; 50th percentile: B = 0.058, SE = 0.024, 95% CI [0.018, 0.110]). The indirect effect of perceived loneliness on mental health via autonomy and relatedness was not moderated by age.

In sum, this study supports the moderated mediation hypothesis (hypothesis 3) regarding competence needs, but not regarding autonomy and relatedness needs. The results indicate that younger people in particular experienced mental health challenges during the lockdown because they felt lonely which can be explained with their perceptions of impaired competence.

Discussion

This study aimed to add to the literature by examining psychological pathways and boundary conditions for the link between perceived loneliness and mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic. The results corroborate that perceived loneliness during the lockdown is significantly and positively related to anxiety and depression. These findings are in line with several studies in the Covid-19 context demonstrating that increased loneliness perceptions during the pandemic resulted in adverse mental health issues in different countries (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Gozansky et al., 2021; Killgore et al., 2020). Drawing on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), we examined the satisfaction of all basic psychological needs (relatedness, autonomy and competence) as psychosocial pathways and found that only competence was a consistent mediator in the relation between loneliness perceptions and mental health.

The satisfaction of competence needs has already been shown to be an important factor for mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic including different samples, such as university students, people with disabilities and the Portuguese general population (Antunes et al., 2020; Bentzen et al., 2021; Holzer et al., 2021). It is conceivable that changes in the social context, as triggered by the lockdown measures, affected the satisfaction of competence needs because social actors were not able to facilitate the satisfaction of this need (La Guardia et al., 2000; La Guardia & Patrick, 2008; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). When people experience loneliness, competence needs are not met which can then reinforce the feeling that difficult tasks cannot be mastered. This may result in increased fear of failure, worry, and doubts about one’s abilities (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Social support prevention measures might counteract the negative effects of loneliness by creating opportunities for social interaction that particularly enhance citizens’ sense of competence, therefore, allowing for optimal psychological functioning and wellbeing.

Contrary to our expectations, relatedness satisfaction did not significantly mediate the perceived loneliness-mental health link. These results seem to be contradicting other studies, which found that all three needs were associated with mental health in the Covid-19 context (Levine et al., 2022; Schutte & Malouff, 2021; Vermote et al., 2022). One possible explanation for our findings may be that many people found other ways to satisfy their relatedness needs, for example, through online contact. Indeed, research found that online support was connected to increased basic need satisfaction and in turn reduced mental health issues in the Covid-19 context (Costa et al., 2022).

Drawing on psychosocial development theory (Erikson, 1968), it was also hypothesized that the psychosocial pathways would be exacerbated among younger age groups. A moderated mediation could only be found in terms of the link between perceived loneliness and competence needs, but not regarding autonomy and relatedness needs. Moreover, there was only a significant indirect effect for age groups that correspond to the phase of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2004). Antunes and colleagues (2020) study also showed that the youngest age group (18 to 34 years) demonstrated the lowest levels of competence need satisfaction and highest levels of anxiety during the Portuguese lockdown. However, the study assessed only bivariate associations between these variables and focused on the first pandemic wave in April of 2020. One possible explanation for the centrality of social interactions to emerging adults’ sense of competence may be the importance of peer observations, encouragement, and feedback from others (Bandura, 1977; Bandura, 1994). There is no research specifically linking social factors to the satisfaction of the need for competence. However, there are some studies that support the link between feedback and related constructs, such as self-efficacy (Brown et al., 2016; Dou et al., 2016). People who rate themselves as self-efficacious are less reluctant to tackle difficult tasks (Bandura, 1977; Bandura 1994). Given the conceptual link between self-efficacy and the need for competence, we suggest that the constraints associated with the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in emerging adults having fewer opportunities to observe how their peers successfully accomplish difficult tasks (Dou et al., 2016), as well as receiving less verbal feedback and encouragement from others because the lockdown provided fewer opportunities for social interactions. Another possible explanation may be that emerging adulthood is a developmental phase where relationships are particularly important (Arnett, 2000). The results suggest that emerging adults were particularly vulnerable to lack social interactions while being in a developmental phase where their need for competence satisfaction still depends on the interaction with other social actors such as peers, teachers and professors (Arnett, 2001; Ryan & La Guardia, 2000). In contrast, older adults may no longer rely as much on the reassurance of other people regarding their competence perceptions.

Future research could explore the psychosocial implications of online teaching in tertiary education via qualitative methods. Bolstering interaction among students even in times of online learning could lead to increased competence feelings which in turn could prevent mental health problems. Universities may consider providing opportunities for continued social exchange despite physical distance.

Limitations that need to be considered are the specific pandemic context of the study, the exclusive use of self-reports, the cross-sectional design which does not allow assumptions about the causality of the results. For instance, longitudinal studies have found a bidirectional association between loneliness and mental health (e.g., Santini et al., 2020). Thus, it should be considered that participants with pre-existing mental health conditions may also be more vulnerable to feelings of loneliness during the pandemic. Future research could address this by using longitudinal designs targeting populations that are known to experience social exclusion, such as social minorities. Longitudinal studies would also allow to investigate whether the found age effects can be attributed to the developmental differences of the age groups or to the specific cohorts. For example, it is conceivable that younger generations are more likely to be exposed to higher performance pressures (Ng et al., 2010), which in turn may be associated with greater problems with the satisfaction of competence needs. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the moderating effect of age stems from another variable such as student-status. Since students have been particularly affected by Covid-related changes, such as having to attend online classes, this might explain how loneliness reduced competence satisfaction (Holzer et al., 2021).

To conclude, to our knowledge, this study is the first to test a comprehensive socio-psychological model of mental health predictors in the Covid-19 context in Portugal. Our study highlights the role of social factors in the satisfaction of competence needs and mental health, particularly among younger people during the Covid-19 lockdown in Portugal. The findings also point to potential avenues for future prevention and interventions, especially in the domain of education to mitigate the harmful effects of social exclusion. Even though, it remains to be shown whether the results extend beyond the pandemic context, it is conceivable that individuals who are lonely and social minorities who are socially excluded may not be able to meet their competence needs. Hence, it might be of utmost importance to create avenues for social interaction and thus ward off the negative impact of social isolation and loneliness.

Notes

Participants who are not Portuguese were asked about their nationality with an open-ended question; a minority indicated being Brazilian (0.3%), while 21% did not answer this question.

We also re-analysed post-Covid data from a separate study with a university student sample from Portugal collected in spring 2023 (N = 243; Age range = 18–42; M = 22.03; SD = 3.30; 68.3% female). Students responded to an adapted version of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale-Work Domain (Kasser et al., 1992) and the Multidimensional Social Support Scale (which can be considered as a proxy for perceived loneliness when there is a perceived lack of social support). Perceived social support was positively associated with competence (B = 0.343, t = 6.008, p < .001), yet age was not a significant predictor of competence (B = 0.010, t = 0.527, p = .599). Most importantly, the interaction effect did not reach significance at an alpha level of 0.05, (B = − 0.029, t = -1.386, p = .167), possibly due to the limited age range. Nevertheless, PROCESS allows probing interactions up to an alpha level of 0.20, and the conditional effects showed highly significant positive slopes for conditional values at the mean values of the moderator (B = 0.437, t = 5.005, p < .001) and values below one standard deviation (B = 0.343, t = 6.001, p < .001). However, the slopes at conditional values of one standard deviation above the mean were only marginally significant (B = 0.249, t = 2.768, p = .006). This supports our findings that social relations are particularly important for competence perceptions in younger age groups.

The conditional effects were evaluated at the 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles of age due to the right-skewed distribution of the age variable. Based on developmental psychology literature, the 16th (age of 20) and 50th (age of 22) percentiles fall into the age range of emerging adults (ranging from age 18 to 29), whereas the 86th (age of 40) percentile represents middle aged adulthood (Arnett, 2004).

References

Antunes, R., Frontini, R., Amaro, N., Salvador, R., Matos, R., Morouço, P., & Rebelo-Gonçalves, R. (2020). Exploring lifestyle habits, physical activity, anxiety and basic psychological needs in a sample of Portuguese adults during covid-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124360.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence through midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026450103225.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ausín, B., González-Sanguino, C., Castellanos, M., Saiz, J., & Muñoz, M. (2022). Longitudinal study of age-realted differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of Covid-19 in a Spanish sample. Behavioral Psychology/ Psicologia Conductual, 30(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.51668/bp.8322105n.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75361-4.

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (pp. 71–81). Cambridge: Academic Press.

Bentzen, M., Brurok, B., Roeleveld, K., Hoff, M., Jahnsen, R., Wouda, M. F., & Baumgart, J. K. (2021). Changes in physical activity and basic psychological needs related to mental health among people with physical disability during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Disability and Health Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101126

Brown, G. T. L., Peterson, E. R., & Yao, E. S. (2016). Student conceptions of feedback: Impact on self-regulation, self-efficacy, and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(4), 606–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12126.

Buecker, S., & Horstmann, K. T. (2021). Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review enriched with empirical evidence from a large-scale diary study. European Psychologist, 26(4), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000453.

Cantarero, K., van Tilburg, W. A. P., & Smoktunowicz, E. (2021). Affirming basic psychological needs promotes mental well-being during the COVID-19 outbreak. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 821–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620942708.

Carson, J., Prescott, J., Allen, R., & McHugh, S. (2020). Winter is coming: Age and early psychological concomitants of the Covid-19 pandemic in England. Journal of Public Mental Health, 19(3), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-06-2020-0062.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Costa, S., Canale, N., Mioni, G., & Cellini, N. (2022). Maintaining social support while social distancing: The longitudinal benefit of basic psychological needs for symptoms of anxiety during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 52(6), 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12870.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

Dimmock, J., Krause, A. E., Rebar, A., & Jackson, B. (2021). Relationships between social interactions, basic psychological needs, and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology and Health, 37(4), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1921178.

Dou, R., Brewe, E., Zwolak, J. P., Potvin, G., Williams, E. A., & Kramer, L. H. (2016). Beyond performance metrics: Examining a decrease in students’ physics self-efficacy through a social networks lens. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020124.

Emery, A. A., Toste, J. R., & Heath, N. L. (2015). The balance of intrinsic need satisfaction across contexts as a predictor of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Motivation and Emotion, 39(5), 753–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11031-015-9491-0.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis New York: WW Norton & Company.

Ernst, M., Niederer, D., Werner, A. M., Czaja, S. J., Mikton, C., Ong, A. D., Rosen, T., Brähler, E., & Beutel, M. E. (2022). Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. The American Psychologist, 77(5), 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001005.

Eryilmaz, A. (2012). A model for subjective well-being in adolescence: Need satisfaction and reasons for living. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 561–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9863-0.

Ferguson, C. J. (2009). An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional psychology. Research and Practice, 40(5), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808.

Gargiulo, R. A., & Stokes, M. A. (2009). Subjective well-being as an indicator for clinical depression. Social Indicators Research, 92(3), 517–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9301-0.

González-Sanguino, C., Ausín, B., Castellanos, M., Saiz, J., López-Gómez, A., Ugidos, C., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Mental health consequences of the coronavirus 2020 pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565474.

Gozansky, E., Moscona, G., & Okon-Singer, H. (2021). Identifying variables that predict depression following the general lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1746. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680768.

Groarke, J. M., Berry, E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P. E., McGlinchey, E., & Armour, C. (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PLOS ONE, 15(9), e0239698. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0239698.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2006.04.002.

Holzer, J., Lüftenegger, M., Korlat, S., Pelikan, E., Salmela-Aro, K., Spiel, C., & Schober, B. (2021). Higher education in Times of COVID-19: University students’ basic need satisfaction, self-regulated learning, and well-being. AERA Open, 7, 23328584211003164. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211003164.

Jackson, J., & Cochran, S. D. (1991). Loneliness and psychological distress. The Journal of Psychology, 125(3), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1991.10543289.

Kasser, T., Davey, J., & Ryan, R. M. (1992). Motivation, dependability, and employee- supervisor discrepancies in psychiatric vocational rehabilitation settings. Rehabilitation Psychology, 37(3), 175–187.

Killgore, W. D. S., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113117. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2020.113117.

Kovacs, B., Caplan, N., Grob, S., & King, M. (2021). Social networks and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Socius, 7, 237802312098525. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120985254.

La Guardia, J. G., & Patrick, H. (2008). Self-determination theory as a fundamental theory of close relationships. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012760

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367.

Lee, C. M., Cadigan, J. M., & Rhew, I. C. (2020). Increases in loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 714–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009.

Levine, S. L., Brabander, C. J., Moore, A. M., Holding, A. C., & Koestner, R. (2022). Unhappy or unsatisfied: Distinguishing the role of negative affect and need frustration in depressive symptoms over the academic year and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Motivation and Emotion, 46(1), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-021-09920-3.

McDonald, A. J., Wickens, C. M., Bondy, S. J., Elton-Marshall, T., Wells, S., Nigatu, Y. T., Jankowicz, D., & Hamilton, H. A. (2022). Age differences in the association between loneliness and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2022.114446

Ng, E. S. W., Schweitzer, L., & Lyons, S. T. (2010). New generation, great expectations: A field study of the millennial generation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9159-4.

Nogueira, J., Gerardo, B., Silva, A. R., Pinto, P., Barbosa, R., Soares, S., Baptista, B., Paquete, C., Cabral-Pinto, M., Vilar, M. M., Simões, M. R., & Freitas, S. (2021). Effects of restraining measures due to COVID-19: Pre- and post-lockdown cognitive status and mental health. Current Psychology, 41(10), 7383–7392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01747-y.

Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade, depressão e stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond E Lovibond. Psicologia Saúde & Doenças, 5(2), 229–239.

Park, C., Majeed, A., Gill, H., Tamura, J., Ho, R. C., Mansur, R. B., Nasri, F., Lee, Y., Rosenblat, J. D., Wong, E., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). The effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 294, 113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514.

Patten, S. B. (2017). Age of onset of mental disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(4), 235–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716685043.

Paulino, M., Dumas-Diniz, R., Brissos, S., Brites, R., Alho, L., Simões, M. R., & Silva, C. F. (2021). COVID-19 in Portugal: Exploring the immediate psychological impact on the general population. Psychology Health and Medicine, 26(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1808236.

Pinho, S., Cruz, M., Dias, C. C., Castro-Lopes, J. M., & Sampaio, R. (2022). Acceptance and adherence to COVID-19 vaccination: The role of cognitive and emotional representations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159268.

Pocinho, M., Farate, C., & Dias, C. (2010). Validação psicométrica Da Escala UCLA-loneliness para idosos portugueses. Interações: Sociedade E Novas Modernidades, 18, 65–77. http://www.interacoes-ismt.com/index.php/revista/article/viewArticle/304.

Ryan, R. M., & La Guardia, J. G. (2000). What is being optimized? Self-determination theory and basic psychological needs. In S. H. Qualls & N. Abeles (Eds.), Psychology and the aging revolution: How we adapt to longer life. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association.

Santini, Z. I., Jose, P. E., Cornwell, Y., Koyanagi, E., Nielsen, A., Hinrichsen, L., Meilstrup, C., Madsen, C., K. R., & Koushede, V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e62–e70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0.

Santos, J. V., Gomes da Costa, J., Costa, E., Almeida, S., Cima, J., & Pita-Barros, P. (2022). Factors associated with non-pharmaceutical interventions compliance during COVID-19 pandemic: A Portuguese cross-sectional survey. Journal of Public Health, 45(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/PUBMED/FDAC001.

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2021). Basic Psychological need satisfaction, affect and Mental Health. Current Psychology, 40(3), 1228–1233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0055-9.

Schwinger, M., Trautner, M., Kärchner, H., & Otterpohl, N. (2020). Psychological impact of Corona lockdown in Germany: Changes in need satisfaction, well-being, anxiety, and depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 9083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239083.

Sousa, S. S., Ribeiro, J. L. P., Palmeira, A. L., Teixeira, P. J., & Silva, M. N. (2012). Estudo Da basic need satisfaction in general scale para a língua portuguesa. Psicologia Saúde & Doenças, 13(2), 209–219.

Sousa, G. M. D., Tavares, V. D. D. O., de Meiroz Grilo, M. L. P., Coelho, M. L. G., Lima-Araújo, G. L. D., Schuch, F. B., & Galvão-Coelho, N. L. (2021). Mental health in COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-review of prevalence meta-analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 703838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703838.

Tian, L., Chen, H., & Huebner, E. S. (2014). The longitudinal relationships between basic psychological needs satisfaction at school and school-related subjective well-being in adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 119, 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0495-4.

Torres, A. R., Rodrigues, A. P., Sousa-Uva, M., Kislaya, I., Silva, S., Antunes, L., Dias, C., & Nunes, B. (2022). Impact of stringent non-pharmaceutical interventions applied during the second and third COVID-19 epidemic waves in Portugal, 9 November 2020 to 10 February 2021: An ecological study. Eurosurveillance, 27(23), 2100497. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2022.27.23.2100497.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359.

Vermote, B., Waterschoot, J., Morbée, S., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Schrooyen, C., Soenens, B., Ryan, R., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2022). Do psychological needs play a role in times of uncertainty? Associations with well-being during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(1), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00398-x.

Weissbourd, R., Batanova, M., Lovison, V., & Torres, E. (2020). Loneliness in America: How the pandemic has deepened an epidemic of loneliness and what we can do about it. Making Caring Common. https://www.makingcaringcommon.org.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants, students and research assistants involved in this study, in particular Irmak Biriz for her help with the post-Covid data analysis in this paper.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict if interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the university´s ethical committee (Nr. 75/2021).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Sloot, R.J.A., Vauclair, CM. Covid-19 Lockdown Loneliness and Mental Health: The Mediating Role of Basic Need Satisfaction Across Different Age Groups. J Adult Dev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09469-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09469-0