Abstract

Relevant literature indicates that one’s perception of future time is related to their psychological well-being, particularly for older adults. However, more research is needed to understand this relationship in the context of COVID-19. Older adults may be especially vulnerable to the psychological impacts of the pandemic, but findings on their psychological well-being during COVID-19 are mixed. The current study examines relationships between Future Time Perspective (FTP), COVID-19 impact, and Psychological Well-Being, and how these variables change over 8 months during the earlier period of the pandemic. The current study explored these relationships in a sample of older women in Ontario, Canada, at two time points (Mage = 70.39 at T1), who completed online Qualtrics surveys. We used hierarchical linear regressions to test our expectations that COVID-19 impact would be negatively associated with psychological well-being, whereas FTP would be positively associated with psychological well-being, and that FTP would moderate the relationship between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being. We found partial support for these hypotheses. Our knowledge of the relationship between FTP and psychological well-being would benefit from research that continues to explore different contexts and diverse samples, to enhance understandings of important differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For the last few years, the physical and psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic—caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus—have been felt across the globe. Researchers have examined mental health impacts throughout different stages of the pandemic, ranging from its unexpected onset, multiple lockdowns, and continuing vaccination disseminations (Kivi et al., 2021; Kotwal et al., 2020). Extant research has used cross-sectional, retrospective, and longitudinal methods across different age groups and countries to explore the ways in which individuals have coped with an enduring global stressor (Luceño-Moreno et al., 2022; Tsamakis et al., 2021). The present study examines potential changes in psychological well-being across several months of the pandemic, as well as the psychological resources used during this time period. Past research indicates that older adults tend to be resilient in the face of global or local stressful events (Adams et al., 2011; Bonanno et al., 2006; Fung & Carstensen, 2006). However, the pandemic may be unique to other comparative sociohistorical crises, given its prolonged time length and the behavioral measures employed to mitigate its spread.

Research comparing mental health outcomes in older and younger adults during COVID-19 thus far has shown older adults to be relatively resilient compared to their younger adult counterparts (Birditt et al., 2021a; Szabo et al., 2020). Within-group research on older adults during the pandemic shows more variance, with some studies demonstrating stable levels of well-being (e.g., Kivi et al., 2021), and other studies indicating poorer mental health outcomes in this population (e.g., Gonçalves et al., 2022). Notably, research has been conducted across different time points and contexts during the pandemic, such as at its inception, during stay-at-home orders, and throughout different lockdown periods. Thus, more research is needed to examine fluctuations in psychological well-being over time. In addition, gender differences in well-being have emerged throughout the pandemic, with women demonstrating poorer outcomes than men on several indices of well-being (Gestsdottir et al., 2021; Horesh et al., 2020). Given the heightened physical vulnerabilities faced by older adults during COVID-19 (Banerjee et al., 2020; Sharma, 2021), calls to focus research efforts on their psychological well-being (Holmes et al., 2020), and noted gender differences, the current study focuses on COVID-19 related psychological well-being among older Canadian women.

Theoretical Framework

The present study draws from Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST; Carstensen, 1992), which recognizes the importance of time in motivating one’s goals (Carstensen, 2021). When time horizons are perceived as long or time is viewed as expansive, people prioritize informational goals, such as the acquisition of knowledge and initiation of new friendships. Conversely, as time horizons grow shorter and are perceived as increasingly limited, emotional goals are prioritized (Carstensen, 2021). Older age is often a motivator for developing perceptions of limited time left (Carstensen et al., 1999). However, sociocultural events can also prime the sense of an ending or the fragility of life, and subsequently the perception that one’s future time is limited; for example, during global pandemics such as the SARS-CoV outbreak in Hong Kong (Fung & Carstensen, 2006), or the recent and on-going outbreak of COVID-19 (Carstensen et al., 2020; Newton et al., 2022). When time horizons are perceived as limited, individuals naturally maximize how they spend their time to focus on positive experiences (e.g., socializing and activities; Carstensen et al., 1999; Carstensen & Fredrickson, 1998; Fung & Carstensen, 2006), which in turn can be positively related to psychological and emotional well-being, particularly among older adults.

The early months of the COVID-19 outbreak provided a context in which people not only perceived the future as uncertain, thus, motivating personal behavior (Morselli, 2013), but were also thwarted in their subsequent attempts to maximize their psychological well-being, due to pre-vaccine health directives such as social distancing and mask wearing. However, research concerning the early psychological impact of the pandemic shows mixed results.

Psychological Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Since its onset, COVID-19 has had significant physical and psychological effects on individuals across the globe (Tyler et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), including those in Canada (Dozois, 2021), with anxiety and depression levels rising concomitantly with infection levels and increased public health restrictions, at least in Alberta and Ontario (Lowe et al., 2022). Though these effects have been documented across different age groups, older adults—often defined as those aged 70+—face unique age-related pandemic concerns, with higher rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit usage, and mortality (Fingerman & Pillemer, 2021). Thus, at the beginning of the pandemic, researchers hypothesized that the psychological impacts of the pandemic would be intensified for older adults, many of whom had already experienced the negative effects of social isolation before the pandemic began (Banerjee et al., 2020; Javadi & Nateghi, 2020). Given these heightened concerns, this population has garnered much attention from public health officials and researchers alike.

Much of the research on the mental health effects of COVID-19 has compared differences between age groups, with older adults exhibiting higher levels of resilience and endorsing lower stress levels relative to their younger adult counterparts (Birditt et al., 2021a; Szabo et al., 2020). Park et al. (2021) found that being older predicted better adjustment to the pandemic, and Birditt et al. (2021a) found that older adults reported fewer life changes than younger adults, demonstrating that older adults have also been able to adapt more easily to the pandemic than younger ones. During COVID-19, age has been associated with comparatively greater psychological well-being for older adults even when controlling for perceived COVID-19 risk (Carstensen et al., 2020). Perhaps these results are unsurprising, given that past research has shown older adults to have relatively high resilience and low distress in response to large-scale events such as the Great Depression, World War II, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and SARS-CoV (Bonanno et al., 2006; Fung & Carstensen, 2006; Settersten et al., 2020).

Other research has explored functioning and responses to the pandemic as well as coping mechanisms and psychological resources among older adults. Although Kivi et al. (2021) found that levels of well-being remained longitudinally stable relative to pre-pandemic functioning, Kotwal et al. (2020) found that older adults who also experienced loneliness were more likely to report higher levels of depression and anxiety as well as poor emotional coping due to COVID-19. In addition, older adults have reported feeling emotionally unstable, with constraints on daily activities and social interactions identified as challenges during COVID-19 (Gonçalves et al., 2022). Despite the different stages of the pandemic entailing various lockdowns, vaccine rollouts and evolving protocols, limited conclusive research exists exploring the ways in which older adult well-being has changed both as a result of and throughout the pandemic. Extant research reveals mixed results. For example, while some research found that loneliness in older adults in the United States increased from pre-pandemic levels during the first year of the pandemic (Goveas et al., 2022; Zaninotto et al., 2022), participants in the New Zealand Health, Work, and Retirement Study exhibited no change in loneliness levels from before the pandemic to during the pandemic in both 2020 and 2021 (Allen et al., 2022). Finally, Mendez-Lopez et al. (2022) found that older adults reported worsened mental health from June to August 2020, but additionally that factors such as experiencing unmet healthcare needs, job loss, financial hardship and being female were associated with increased risk of deteriorating mental health. Unforeseen events, such as unexpected job loss or early retirement and subsequent financial insecurity, can trigger thoughts related to time left to live, particularly among older adults, and particularly if those time horizons appear bleak or limited.

Future Time Perspective

Based in Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST; Carstensen, 1992, 2021), the notion of proximity to death often prompts a shift in the perception of time horizons and is associated with individuals’ motivations and goals as well as psychological well-being. While Carstensen et al. (2020) found that the perception of less time left in life was more beneficial for older adults’ psychological well-being compared to that of younger adults during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, other studies of older adults have found that perceptions of extended futures are generally associated with higher well-being (Brothers et al., 2016; Demiray & Bluck, 2014; Kotter-Grühn & Smith, 2011). For example, both Brothers et al. (2016) and Demiray and Bluck (2014), using the Future Time Perspective scale (FTP) developed by Carstensen and Lang (1996) to measure SST-related perceptions of time horizons, found that midlife-to-older adults with higher reported FTP (i.e., broader future time horizons) also reported better psychological well-being.

However, patterns between perceptions of time horizons and psychological well-being are not only age-related; they can be altered by reminding us of life’s fragility and the importance of spending time with those close to us through uncertain times such as socio-political events or pandemics that are out of an individuals’ direct control (Morselli, 2013). Thus, while there may be a strong association between FTP and psychological well-being, context plays a moderating role, as evidenced in the study by Fung and Carstensen (2006) during the earlier outbreak of SARS-CoV in Hong Kong, 2002–2003, in which they found that the prevalence and uncertainty of the course of the disease prompted people of all ages to rate their perceived time left as limited.

Psychological Well-Being

The current study focuses on psychological well-being’s relationship to future time perspective (FTP) using Ryff’s (1989) Psychological Well-Being (PWB) scale. According to SST, focusing on time left to live motivates individuals to maximize their activities to those that promote experiences of increased psychological well-being, such as spending time with close loved ones. While our focus is on the FTP-PWB relationship in later life, other correlates and predictors of psychological well-being in older adulthood include health, felt age, and living arrangements (Alonso Debreczeni & Bailey, 2020; Jivraj & Nazroo, 2014; Palgi et al., 2014; Russell & Taylor, 2009; Steptoe et al., 2015). For instance, research demonstrates that physical illnesses and having a chronic health condition are negatively associated with psychological well-being in older adults (Jivraj & Nazroo, 2014; Steptoe et al., 2015). Having a low subjective age or felt age—how old one feels—is associated with enhanced subjective well-being, reduced depressive symptoms, and lower levels of psychological distress (Alonso Debreczeni & Bailey, 2020; Palgi et al., 2014). In terms of the pandemic, Shrira et al. (2020) found that, in a sample of older Israelis, the positive association between feeling lonely and poor well-being was weakened by feeling younger. Older adults’ living arrangements can also be related to psychological well-being, with older adults who live alone displaying lower levels of psychological well-being compared with those who live with others (Russell & Taylor, 2009). During COVID-19, the impacts of living alone have been particularly salient with the advent of social distancing and stay-at-home orders: older adults living alone reported greater increases in feelings of loneliness, social isolation, and less perceived support compared to those living with others (Wilson-Genderson et al., 2021), with the strongest effects experienced among older adult women living alone.

Beyond the COVID-19 context, research exploring psychological well-being in older adult women is especially important, given gender differences in mortality: women tend to outlive men by 4 to 7 years (Ginter & Simko, 2013). Despite living longer, older women’s health tends to be poorer relative to older men’s health, with women reporting higher rates of disease and disability in later life (Crimmins & Beltrán-Sanchez, 2010). Given gender differences in health, and the differences in psychological well-being during the pandemic between women and men, it is important to focus research efforts on this population. Thus, the present study focuses exclusively on psychological well-being in older adult women.

The Current Study

Based on the literature outlined above, the present study examines the relationship between FTP and psychological well-being during the pandemic, and how these variables change over time in the context of COVID-19. Older Canadian women aged 59–88 filled out two surveys at different time points in the COVID-19 pandemic, with the first one in July–September 2020 and the second one in March–May 2021. Our main research questions focused on potential changes in psychological well-being for older Canadian women, and the correlates associated with their psychological well-being over approximately 8 months. We examined changes in COVID-19 impact, the Future Time Perspective scale (FTP; Carstensen & Lang, 1996), and Psychological Well-Being (Ryff, 1989) between the two time periods, as well as associations between the impact of COVID-19, psychological well-being and FTP. Additionally, we assessed the role of the FTP scale as a moderator of the relationship between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being. Health, felt age, and living arrangements were included as covariates, given their historic associations with and continuing importance for psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic (Alonso Debreczeni & Bailey, 2020; Banerjee et al., 2020; Wilson-Genderson et al., 2021).

We had no hypotheses regarding changes in levels of COVID-19 impact, FTP, or psychological well-being, so this was an exploratory first step. However, we had two related, specific hypotheses:

(1) Based on findings indicating that older adults have experienced poorer mental health outcomes during the pandemic (Gonçalves et al., 2022; Kotwal et al., 2020; Mendez-Lopez et al., 2022) and research indicating that perceptions of expansive futures are associated with higher well-being (Brothers et al., 2016; Demiray & Bluck, 2014; Kotter-Grühn & Smith, 2011), we hypothesized that COVID-19 impact would be negatively associated with psychological well-being whereas FTP would be positively associated with psychological well-being over and above health, felt age, and living alone. Additionally, we also expected that (2) the relationship between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being would be moderated by participants’ future time perspective. Specifically, that those with high levels of COVID-19 impact would have lower levels of psychological well-being if they had lower levels of FTP compared to those experiencing similar levels of COVID-19 impact but higher levels of FTP.

Method

Participants

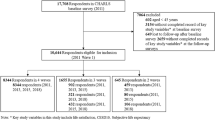

Participants were recruited from the Greater Toronto Area, including the Kitchener-Waterloo area. The first survey (T1) consisted of N = 190 female participants, who were recruited using two recruitment methods. Some of the women were recruited from the principal investigator’s (PI’s) existing database of older women who have previously participated in the PI’s research studies (N = 38) and were invited to participate in the first survey. The rest of the sample was recruited through Dynata.com (N = 152), a provider of participant panels to researchers. Sample age at the first survey (T1) was 59–88 (Mage = 70.39, SD = 4.61). The majority of participants self-identified as White (88.3%), with 7.4% Asian, Black (2.5%), and Other (1.9%). Most women (83.7%) were unemployed or not working; 87.8% reported living in large cities/population centers. Approximately half (50.3%) of the women were married or had a live-in partner, 21.7% were divorced or separated, and 10.6% were single; 43.9% of women reported living alone, with median household income ranging between $40,000 and $100,000. Lastly, 72% of women had children and 53.2% had grandchildren.

After the first survey, participants were re-contacted and given the option to complete a second survey. Of the original 190 participants, 106 women (56%) completed the second survey. Those who did not complete the second survey were unresponsive to multiple follow-up contacts by the research team. The average age of the sample for the second survey (T2) was Mage = 70.73, with similar sample demographics (race/ethnicity, marital status, living situation) as those reported for the first survey; Table 1 displays available sample demographics for both T1 and T2.

Study Procedure

Data were collected from the sample at two points throughout the COVID-19 pandemic: Summer 2020 (T1) and Winter/Spring 2021 (T2). Importantly, the COVID-19 landscape differed during the two data collection periods. The first round of data collection (T1) pre-dated the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and marked the re-opening of restaurants, malls, and recreational centres. During the second round of data collection (T2), COVID-19 vaccine distribution had commenced but Ontario was experiencing a lockdown and a surge of COVID-19 infections in the community.

Measures

The study used quantitative measures to assess psychological well-being, future time perspective, and the impact of COVID-19, which were all measured at both survey time points (T1 and T2). The covariates of felt age and living arrangements were measured at both T1 and T2; self-rated health was measured only at T1. Table 1 displays variable descriptives at both time points.

Psychological Well-Being

The Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWB; Ryff, 1989) was used to measure participants’ psychological well-being. The PWB scale is comprised of six subscales: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, positive relations with others, and self-acceptance (Ryff, 1989). The version of the scale used in the present study consists of 21 items comprising three subscales, each with 7 items: personal growth, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. These subscales reflect individuals’ emotional attitudes and behaviors and are in line with those used in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS; Smith et al., 2017). Participants rated their level of agreement from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. The scale points used in the present study were reversed from the original scale (1 = strongly agree to 6 = strongly disagree); thus, higher scores indicated positive psychological well-being. Example items included questions such as “I like most aspects of my life,” and “When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out.” Reliability at T1 was high, α = 0.91 with M = 4.42 (SD = 0.68), with similar reliability at T2, α = 0.91 with M = 4.50, (SD = 0.71).

Future Time Perspective

Perceptions of the future were measured using the 10-item Future Time Perspective scale (FTP; Carstensen & Lang, 1996). Example items include “I have a sense that time is running out” (reverse scored), “I expect that I will set new goals in the future,” and “Most of my life lies ahead of me.” Participants rated how descriptive each item was regarding their feelings about their life, ranging from 1 (not at all descriptive) to 3 (very descriptive), with higher scores representing a more expansive future time perspective. Carstensen and colleagues reported high reliability for the FTP scale, α = 0.93. In the present study, reliability was α = 0.88 at T1, with M = 1.82, (SD = 0.44). Reliability at T2 was similar to T1: α = 0.86, with M = 1.77 (SD = 0.44).

The Impact of COVID-19

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was assessed using a modified version of Svob and colleagues’ Transition Impact Scale (Svob et al., 2014) to reflect the specific impact of COVID-19. In the original scale, participants are asked to choose one of 12 major life events that occurred in the past 5 years and was important to their life, and to answer a set of items pertaining to the event that start with the stem “This event has…,” for example, “changed the activities I engage in,” or “changed the people I spend time with.” In the current study, participants were given the stem “COVID-19 has…” and asked to rate the same set of items with COVID-19 in mind. A sample item was “COVID-19 has…” “changed the places where I spend time.” Responses ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The mean score for the COVID-19 Impact Scale was 3.15 (SD = 0.65) at T1 and M = 3.30, (SD = 0.62) at T2, with reliabilities α = 0.81 (T1) and α = 0.82 (T2). These descriptives are close to the original Transition Impact Scale (Svob et al., 2014) descriptives also measured in the current study but only at T1: M = 3.15 (SD = 0.81), α = 0.85.

Covariates

The covariates of health, felt age, and living arrangements were included in the current study. Participants rated their health (only at T1) from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) in response to the question, “How would you rate your general state of health in the last 12 months?” On average, self-rated health was 3.44, SD = 0.94. Felt age was measured with the question, “What age do you feel like most of the time?” (Kaufman & Elder, 2002). On average at T1, participants were 70.39 years of age, SD = 4.61 (age range: 59–88 years) and felt on average 56.24 years, SD = 11.85 (age range: 10–85 years). Responses were similar at T2, as participants were on average 70.73 years of age, SD = 5.01 (age range: 60–89) and felt, on average, 58.95 years, SD = 10.70 (age range: 30–85 years). Lastly, participants were asked “Does anyone else beside you live in your household?” with 56.1% (T1) and 56.4% (T2) answering “yes,” indicating they lived with someone else.

Analysis Plan

Correlations were conducted to ascertain relationships between variables at T1 and T2. T tests examined our exploratory question about any possible differences between T1 and T2 in levels of COVID-19 impact, FTP, and psychological well-being. To test hypotheses 1 and 2 concerning the contribution of independent variables to PWB, and the moderation by FTP of the relationship between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being at both T1 and T2, two separate hierarchical linear regressions were conducted. In the first regression analysis, T1 covariates and variables were entered; in the second regression, the same T2 covariates and variables were entered, although we used T1 health again in the second regression given the availability of these data.

Results

Table 2 displays correlations between all variables of interest at the two data collection time points (T1: July–September 2020; T2: March–May 2021). Only participants who completed the surveys at both T1 and T2 were included in these analyses. T1 correlations are displayed below the diagonal; T2 correlations above the diagonal. At T1, COVID-19 impact was negatively related to psychological well-being, whereas FTP was positively related to psychological well-being. At T2, the relationship between FTP and psychological well-being held, but the association between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being was not significant at T2.

Paired-sample t tests examined potential changes in levels of FTP, COVID-19 impact, and psychological well-being over the time period of the study. While there was no significant difference between levels of psychological well-being between T1 and T2, COVID-19 impact increased, t(103) = 3.06, p = 0.003, and FTP decreased, t(103) = 2.27, p = 0.025, between T1 and T2.

To test the hypotheses concerning the degree to which perceived future time and the impact of COVID-19 contributed to women’s psychological well-being at different time points (T1 and T2), and the potential moderation of the relationship between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being by FTP, two separate hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted, with T1 variables analyzed in the first regression and T2 variables analyzed in the second one. Results are presented in Tables 3 (T1) and 4 (T2). For each regression analysis, covariates were entered into the first step of the regression, FTP and COVID-19 impact in the second step of their respective hierarchical regression, and the interaction term (using mean-centered variables) was entered in the third step for each model.

Regarding our first hypothesis that the impact of COVID-19 would be negatively associated with psychological well-being whereas FTP would be positively associated with psychological well-being, we found that the overall model at T1 (see Table 3) was significant, F (6,178) = 25.642, p < 0.001 and that the model accounted for 46% of the variance in psychological well-being. Over and above health, felt age, and living alone, COVID-19 impact was negatively related to psychological well-being, ß = − 0.28, p < 0.001, and FTP was positively associated with psychological well-being, ß = 0.52, p < 0.001. The regression results for T2 (see Table 4) also show that the overall model was significant, F (6, 94) = 12.689, p < 0.001, and that the model accounted for 45% of the variance in psychological well-being. Over and above health, felt age, and living alone, FTP was positively related to psychological well-being, ß = 0.44, p < 0.001; however, COVID-19 impact was not associated with psychological well-being, ß = − 0.04, p = 0.66.

The results for our second hypothesis concerning the moderation by FTP of the COVID-19 impact-psychological well-being relationship at both T1 and T2 show that the moderation was not significant; thus, this hypothesis was not supported.

Discussion

The present study explored psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic for older adult Canadian women and examined relationships between Future Time Perspective (FTP, as related to Socioemotional Selectivity Theory; Carstensen, 1992), Psychological Well-Being (PWB; Ryff, 1989) and COVID-19 impact. Findings indicate that the impact of COVID-19 increased over time while levels of FTP decreased over time. Our first hypothesis was partially supported: At T1, COVID-19 impact was negatively related to psychological well-being above health, felt age and living alone, and FTP was positively related to psychological well-being above the entered covariates. However, at T2, while FTP remained positively related to psychological well-being above health, felt age and living alone, COVID-19 impact was not related to psychological well-being. Additionally, our second hypothesis was not supported: we found no moderation by FTP of the relationship between COVID-19 impact and psychological well-being at both time points.

It is interesting to note that although the impact of COVID increased between the two time points, its association with psychological well-being was significant only at time 1 and not time 2. This is contrary to previous findings by Newton et al. (2022), who examined a similar relationship between early COVID impact and the PWB Purpose in Life subscale (Ryff, 1989); however, the current study uses three subscales of the Psychological Well-Being scale and focuses on data from the same sample also collected later in the pandemic. Perhaps the fact that there was no difference in levels of psychological well-being whereas COVID-19 impact levels increased between T1 and T2 also indicates participants’ adjustment to the situation, or a growing familiarity or resilience. It is also possible that the increased availability of vaccines between T1 (Summer 2020) and T2 (Winter/Spring 2021) provided some hope for moving forward by T2.

Responses to the COVID-19 Impact scale items show evidence that these women found other ways to communicate and socialize within the confines of public health directives. While we did not measure resilience specifically, findings also suggest individual differences in the capacity to adjust to the COVID-19 context. Conversely, the 8-month gap between measurements might have been either too long or too short to capture any meaningful fluctuations in psychological well-being during what has, with hindsight, proved to be merely the initial stages of the pandemic.

Possessing a more positive perception of a future time horizon suggests that the ability to set new goals and continuing to believe there is lots of life left to live when faced with the significant daily impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is an adaptive strategy. The women in the current study continued to remain relatively positive despite being highly impacted by the pandemic, through goal setting and viewing their futures as expansive. Maintaining an expansive time horizon could prove to be a useful tool in the management of psychological well-being during future global crises.

The present study’s findings also suggest that, while COVID impact increased, thus, prompting the sense of an ending, personal resources and social context were equally important to continued psychological well-being. While not highlighted in this study, we also collected qualitative data from the current study sample which, at first glance, provides some evidence for this idea. Participants were asked “Please describe how COVID-19 might have affected your day-to-day life in the last few months. For example, what was life like for you in February, 2020, and had it changed in any perceptible ways by April 2020? What is life like for you now?” Responses highlight both the importance of close relationships and the perception of time, as well as variability in the degree of impact COVID-19 had for these women. For example, one participant responded: “I have…found joy in living in the present, appreciating family, friends…Once the period of grieving my previous life was over, I was able to focus on doing things that bring me happiness.” Another participant stated

Life has been precious to me this past year. I miss actually being with my married children and grandchildren... I have made it a point to telephone about 12 people each month, and I phone weekly my closest friends and siblings.

Another commented: “There is something nice about having unscheduled time, all the time.” Thus, it is essential to acknowledge the complexity and variety of responses to the on-going COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has some limitations, which also suggest future directions. The sample is relatively small, and not representative of all older women living in the Greater Toronto Area nor indeed all women in the province of Ontario and beyond. The sample is predominantly White; therefore, our findings do not capture documented cultural differences in responses to COVID-19. For example, Birditt et al. (2021b) found that non-White women reported more stress and depressive symptoms during the pandemic. Additionally, while it was intentional to include only women in the sample, given that women have tended to exhibit lower psychological well-being during COVID-19 (Gestsdottir et al., 2021; Horesh et al., 2020), a comparative analysis of older men would also enrich our understanding of COVID-19’s association with psychological well-being and the personal resources that potentially moderate this relationship.

In terms of measures, we used a one-item self-rated measure of health at time 1 only—an oversight on our part. A fuller measure of perceived health or physician-diagnosed conditions taken at both time points would provide a fuller picture of participants’ current health status. In addition, participants were not asked whether they or other household members had caught the COVID-19 virus. This information would be important to include in future studies, as it could affect participants’ psychological and physical well-being, as well as their perceptions of the future.

Data were collected during the earlier stages of the pandemic, before vaccines were widely available, so all variables of interest did not include pre-COVID-19 levels. Including these data, where available, in future studies will help to clarify the scope of COVID-19-related changes in perspectives of future time horizons and psychological well-being. Initial indications from qualitative data collected at time 2 point to the importance of having an expansive time horizon during COVID-19, particularly in relation to psychological well-being. Thus, a more detailed analysis of these qualitative data would help to flesh out the current study’s findings.

Conclusion

The current study examined the relationship between future time perspective, the impact of COVID-19, and psychological well-being among older Canadian women during a relatively early period of the pandemic. Findings outline that although levels of time perspectives and psychological well-being changed over the 8 months of the study (July–September 2020 to March–May 2021), having an expanded time horizon is beneficial to psychological well-being at both time points—particularly at time 2—over and above the on-going COVID-19 context. Continued research is needed to explore the on-going use of future time perspective as a psychological resource to cope with elements of global crises; it would also be helpful to continue to explore changes in older adult well-being as the pandemic and its impacts continue to unfold.

References

Adams, V., Kaufman, S. R., van Hattum, T., & Moody, S. (2011). Aging disaster: Mortality, vulnerability, and long-term recovery among Katrina survivors. Medical Anthropology, 30(3), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.560777

Allen, J., Uekusa, S., Tu, D., Stevenson, B., Stephens, C., Alpass, F. (2022). Short term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and response on older adults: Findings from the Health, Work and Retirement study. Massey University. Retrieved from https://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/fms/Colleges/College%20of%20Humanities%20and%20Social%20Sciences/Psychology/HART/publications/reports/2022_COVID19_HWR_Report.pdf?A1956343EBFA63FFE903F6C6375C3BD1.

Alonso Debreczeni, F., & Bailey, P. E. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of subjective age and the association with cognition, subjective well-being, and depression. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(3), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa069

Banerjee, A., Pasea, L., Harris, S., Gonzalez-Izquierdo, A., Torralbo, A., Shallcross, L., Noursadeghi, M., Pillay, D., Sebire, N., Holmes, C., Pagel, C., Wong, W. K., Langenberg, C., Williams, B., Denaxas, S., & Hemingway, H. (2020). Estimating excess 1-year mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic according to underlying conditions and age: A population-based cohort study. The Lancet, 395(10238), 1715–1725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30854-0

Birditt, K. S., Turkelson, A., Fingerman, K. L., Polenick, C. A., & Oya, A. (2021a). Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa204

Birditt, K. S., Oya, A., Turkelson, A., & Fingerman, K. L. (2021b). Race differences in COVID-19 stress and social isolation: Cross sectional and longitudinal links with depressive symptoms. In Paper presented at the meeting of the Gerontological Society of America. .

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster. Psychological Science, 17(3), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01682.x

Brothers, A., Gabrian, M., Wahl, H. W., & Diehl, M. (2016). Future time perspective and awareness of age-related change: Examining their role in predicting psychological well-being. Psychology and Aging, 31(6), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000101

Carstensen, L. L. (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.331

Carstensen, L. L. (2021). Socioemotional selectivity theory: The role of perceived endings in human motivation. The Gerontologist, 61(8), 1188–1196. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab116

Carstensen, L. L., & Fredrickson, B. F. (1998). Socioemotional selectivity in healthy older people and younger people living with the human immunodeficiency virus: The centrality of emotion when the future is constrained. Health Psychology, 17(6), 494–503.

Carstensen L. L., & Lang F. R. (1996). Future time perspective scale. Stanford University. Unpublished Manuscript.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.54.3.165

Carstensen, L. L., Shavit, Y. Z., & Barnes, J. T. (2020). Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Science, 31(11), 1374–1385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620967261

Crimmins, E. M., & Beltrán-Sanchez, H. (2010). Mortality and morbidity trends: Is there compression of morbidity? The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq088

Demiray, B., & Bluck, S. (2014). Time since birth and time left to live: Opposing forces in constructing psychological wellbeing. Ageing and Society, 34(7), 1193–1218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000032

Dozois, D. J. A. (2021). Anxiety and depression in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Canadian Psychology, 62(1), 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000251

Fingerman, K. L., & Pillemer, K. (2021). Continuity and changes in attitudes, health care, and caregiving for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(4), e187–e189. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa231

Fung, H. H., & Carstensen, L. L. (2006). Goals change when life’s fragility is primed: Lessons learned from older adults, the September 11 attacks and SARS. Social Cognition, 24(3), 248–278. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2006.24.3.248

Gestsdottir, S., Gisladottir, T., StefanSDottir, R., Johannsson, E., JakobSDottir, G., & RognvaldSDottir, V. (2021). Health and well-being of university students before and during COVID-19 pandemic: A gender comparison. PLoS ONE, 16(12), e0261346–e0261346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261346

Ginter, E., & Simko, V. (2013). Women live longer than men. Bratislavske Lekarske Listy, 114(2), 45–49. https://doi.org/10.4149/bll_2013_011

Gonçalves, A. R., Barcelos, J. L. M., Duarte, A. P., Lucchetti, G., Gonçalves, D. R., Silva e Dutra, F. C. M., & Gonçalves, J. R. L. (2022). Perceptions, feelings, and the routine of older adults during the isolation period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study in four countries. Aging & Mental Health, 26(5), 911–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891198

Goveas, J. S., Ray, R. M., Woods, N. F., Manson, J. E., Kroenke, C. H., Michael, Y. L., Shadyab, A. H., Meliker, J. R., Chen, J., Johnson, L., Mouton, C., Saquib, N., Weitlauf, J., Wactawski-Wende, J., Naughton, M., Shumaker, S., & Anderson, G. L. (2022). Associations between changes in loneliness and social connections, and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: The women’s health initiative. The Journals of Gerontology. Series a, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 77(S1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glab371

Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., & Sweeney, A.., et al. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Horesh, D., Kapel Lev-Ari, R., & Hasson-Ohayon, I. (2020). Risk factors for psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: Loneliness, age, gender, and health status play an important role. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(4), 925–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12455

Javadi, S. M. H., & Nateghi, N. (2020). COVID-19 and its psychological effects on the elderly population. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 14(3), e40–e41. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.245

Jivraj, S., & Nazroo, J. (2014). Determinants of socioeconomic inequalities in subjective well- being in later life: A cross-country comparison in England and the USA. Quality of Life Research, 23(9), 2545–2558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0694-8

Kaufman, G., & Elder, G. H. (2002). Revisiting age identity. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0890-4065(02)00042-7

Kivi, M., Hansson, I., & Bjälkebring, P. (2021). Up and about: Older adults’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Swedish longitudinal study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(2), e4–e9. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa084

Kotter-Grühn, D., & Smith, J. (2011). When time is running out: Changes in positive future perception and their relationships to changes in well-being in old age. Psychology and Aging, 26(2), 381–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022223

Kotwal, A. A., Holt-Lunstad, J., Newmark, R. L., Cenzer, I., Smith, A. K., Covinsky, K. E., Escueta, D. P., Lee, J. M., & Perissinotto, C. M. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco Bay Area older adults during the COVID -19 shelter-in-place orders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16865

Lowe, C., Keown-Gerrard, J., Ng, C. F., Gilbert, T. H., & Ross, K. M. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic mental health trajectories: Patterns from a sample of Canadians primarily recruited from Alberta and Ontario. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000313

Luceño-Moreno, L., Talavera-Velasco, B., Vázquez-Estévez, D., & Martín-García, J. (2022). Mental health, burnout, and resilience in healthcare professionals after the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 64(3), 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002464

Mendez-Lopez, A., Stuckler, D., McKee, M., Semenza, J. C., & Lazarus, J. V. (2022). The mental health crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults and the role of physical distancing interventions and social protection measures in 26 European countries. SSM—Population Health, 17, 101017–101017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.101017

Morselli, D. (2013). The olive tree effect: Future time perspective when the future is uncertain. Culture & Psychology, 19(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067x13489319

Newton, N. J., Huo, H., Hytman, L., & Ryan, C. T. (2022). COVID-related perceptions of the future and purpose in life among older Canadian women. Research on Aging. https://doi.org/10.1177/01640275221092177

Palgi, Y., Bodner, E., & Shrira, A. (2014). The interactive effect of subjective age and subjective distance-to-death on psychological distress of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 18(8), 1066–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.915925

Park, C. L., Finkelstein-Fox, L., Russell, B. S., Fendrich, M., Hutchison, M., & Becker, J. (2021). Psychological resilience early in the COVID-19 pandemic: Stressors, resources, and coping strategies in a national sample of Americans. American Psychologist, 76(5), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000813

Russell, D., & Taylor, J. (2009). Living alone and depressive symptoms: The influence of gender, physical disability, and social support among Hispanic and non-Hispanic older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series b, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbn002

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Settersten, R. A., Bernardi, L., Härkönen, J., Antonucci, T. C., Dykstra, P. A., Heckhausen, J., Kuh, D., Mayer, K. U., Moen, P., Mortimer, J. T., Mulder, C. H., Smeeding, T. M., van der Lippe, T., Hagestad, G. O., Kohli, M., Levy, R., Schoon, I., & Thomson, E. (2020). Understanding the effects of COVID-19 through a life course lens. Advances in Life Course Research, 45, 100360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100360

Sharma, A. (2021). Estimating older adult mortality from COVID-19. The Journals of Gerontology. Series b, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), e68–e74. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa161

Shrira, A., Hoffman, Y., Bodner, E., & Palgi, Y. (2020). COVID-19-related loneliness and psychiatric symptoms among older adults: The buffering role of subjective age. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(11), 1200–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.018

Smith, J., Ryan, L., Sonnega, A., & Weir, D. (2017). HRS psychosocial and lifestyle questionnaire, 2006–2016. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Retrieved from https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/publications/biblio/9066.

Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet, 385, 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61489-0

Svob, C., Brown, N. R., Reddon, J. R., Uzer, T., & Lee, P. J. (2014). The transitional impact scale: Assessing the material and psychological impact of life transitions. Behavior Research Methods, 46(2), 448–455. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0378-2

Szabo, A., Ábel, K., & Boros, S. (2020). Attitudes toward COVID-19 and stress levels in Hungary: Effects of age, perceived health status, and gender. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(6), 572–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000665

Tsamakis, K., Tsiptsios, D., Ouranidis, A., Mueller, C., Schizas, D., Terniotis, C., Nikolakakis, N., Tyros, G., Kympouropoulos, S., Lazaris, A., Spandidos, D. A., Smyrnis, N., & Rizos, E. (2021). COVID-19 and its consequences on mental health (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 21(3), 244–244. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.9675

Tyler, C. M., McKee, G. B., Alzueta, E., Perrin, P. B., Kingsley, K., Baker, F. C., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2021). A study of older adults’ mental health across 33 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105090

Wang, C., Tee, M., Roy, A. E., Fardin, M. A., Srichokchatchawan, W., Habib, H. A., Tran, B. X., Hussain, S., Hoang, M. T., Le, X. T., Ma, W., Pham, H. Q., Shirazi, M., Taneepanichskul, N., Tan, Y., Tee, C., Xu, L., Xu, Z., & Vu, G. T., et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: A study of seven middle-income countries in Asia. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0246824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246824

Wilson-Genderson, M., Heid, A. R., Cartwright, F., Collins, A. L., & Pruchno, R. (2021). Change in loneliness experienced by older men and women living alone and with others at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Research on Aging, 44(5–6), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/01640275211026649

Zaninotto, P., Iob, E., Demakakos, P., & Steptoe, A. (2022). Immediate and longer-term changes in the mental health and well-being of older adults in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(2), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3749

Funding

This study was funded by a 2020 Canadian Government Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight Grant awarded to the last author (435-2020-1183).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hytman, L., Hemming, M., Newman, T. et al. Future Time Perspective and Psychological Well-Being for Older Canadian Women During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Adult Dev 30, 393–403 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09445-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-09445-8