Abstract

Graduating from higher education is characterized by a complex set of changes, including the transition into employment as well as residential changes and identity shifts. We explored how wellbeing and depressive symptoms are associated with retrospective appraisals of developmental crisis in the year after leaving university, and the impact of living with parents following graduation. Data were collected from graduates based in the UK over the course of the 12 months following completing an undergraduate degree, via a 3-phase longitudinal design. One-third of the sample reported experiencing a developmental crisis within the year following university. Those who reported a crisis scored significantly lower on measures of environmental mastery across all time points and higher on measures of depression. Those living with parents scored significantly lower on measures of self-acceptance and autonomy and higher on measures of depression. In light of these findings, we conclude that interventions and targeted support to help students manage the psychological challenges of life after university should be developed and implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Graduating from higher education is a multi-faceted and complex life transition. Upon leaving university, graduates experience shifts across a variety of life domains including relationships, friendship networks, personal finances, work, residence, recreation and daily routine (Robinson 2019). There are major challenges to self-identity as individuals transition from their role as a student to the more autonomous role of a young professional (Crebert et al. 2004). Indeed, there are few transitions in adult life during which such significant life domain changes occur within a short space of time. This makes the post-university transition arguably one of the most challenging turning points of adult life, yet it has been rarely studied in terms of its effects on identity, mental health and wellbeing. In this introduction, we briefly define a set of relevant concepts and theories—life transition, emerging adulthood, and quarter-life crisis—before reviewing the literature on the post-university transition.

Transitions are qualitative changes in a person’s psychosocial life structure. In other words, they are changes in kind, rather than change in amount (Robinson 2013). In the case of the post-university transition, a key qualitative change is from being a student to a worker (or unemployed in some cases). Transition periods require the dismantling of pre-existing life structures to make way for new ones, and with this disintegration and fragmentation of existing structures comes a high probability of crisis. A developmental crisis is a transitional episode in life during which a person struggles to cope (with changing demands?) and is forced to question their social environment and their sense of self while exploring new ways of behaving (Robinson and Wright 2013; Slaikeu 1990). Crisis episodes are distressing but common developmental phenomena. They have been argued, by many developmental theorists, to be functional insofar as they stimulate adults to evolve their behavioural repertoire to find an increased level of inner–outer balance and hierarchical integration (Erikson 1968; Levinson 1978, 1996; Robinson 2013).

Crises can affect a person’s life on various levels. At the psychophysical level there will be high levels of stress and a mixture of powerful negative and positive emotions (Lazarus 2000). At the level of identity and meaning, a person in crisis will often question their own beliefs, identity and “personal paradigm” (O’Connor and Wolfe 1991). At the interpersonal level, crises can lead to alterations and disruptions to roles, relationships and systems of social support (Slaikeu 1990). At the socio-cultural level, crises often involve a re-consideration of one’s relationships with social structures and norms, and whether they are just and worth upholding (Crafter and Maunder 2012).

For the majority of graduates, the transition out of higher education occurs within the life stage of emerging adulthood (Arnett 2000; Arnett 2016). This period is defined by high levels of instability in relationships and residence, ambiguity in adult status and a high level of self-examination and self-exploration. Higher education has been found to foster a form of ‘semi-autonomy’ that defines this life stage, and indeed emerging adulthood can be construed as a life stage that has evolved in tandem with the rising popularity of higher education (Arnett 2016).

As a person endeavours to move out of the unstable and footloose life structure that defines emerging adulthood, into more stable adult roles such as long-term relationships, long-term residence and stable employment, the kind of crisis that they encounter is referred to as a quarter-life crisis (Robinson 2016). Such crises can be encountered in two forms, the locked-out form (feeling unable to enter adult roles) or the locked-in form (feeling trapped in newly acquired adult roles). In the locked-out form of quarter-life crisis, individuals feel unable to access meaningful adult roles, for example gaining employment, forming stable relationship, or become residentially and financially independent. Locked-out crisis is likely to be prevalent in the post-university transition, given the challenges of seeking work during this time (Robinson 2019).

For mature students who graduate after the period of emerging adulthood, the post-university transition brings other challenges. Although evidence suggests that mature students generally do well in finding employment after university (Woodfield 2011), they may find themselves with a higher level of worry over financial concerns and debt than traditional age students after leaving university (Cooke et al. 2004), and find that some graduate career paths are biased towards younger applicants (Hill 2012).

The Post-university Transition

The process of leaving higher education and searching for work brings with it a range of potential stressors (Chang and Hancock 2003; Johnson 1991). Recent developments in the higher education sector in the UK have added to the potential for stress after graduating. The expansion of higher education has meant that there are now many more students competing for graduate-level jobs than in the past (Purcell and Elias 2004). Given that almost half of young people now get a degree, the value of a degree is increasingly in question (Bathmaker 2003). Furthermore, the nature of what constitutes a suitable graduate job has been a point of controversy and debate (Purcell and Elias 2004). A further change affecting the experience of the post-university transition is the rise in tuition fees, leading to higher levels of debt upon graduation.

Around half of UK graduates enter a period of relative limbo after leaving university, during which they remain unemployed or attain non-graduate work to build up relevant experience and wait for a full-time paid graduate opportunity to open up (CIPD 2017). Unemployment can lead to self-esteem decline, anxiety and depression in young adults (Feather and Bond 1983; Ryan 2001). Many young graduates express surprise at how difficult it is to gain access to their desired area of work (Pollard et al. 2004). Even when recent graduates find employment, challenges may continue as they may struggle to adjust from the formally assessed learning style of higher education to the informal task-based learning style of the workplace (Candy and Crebert 1991).

A previous study following young individuals from adolescence into emerging adulthood found that perceived failure or underachievement in education and employment can predict increased sense of entrapment, higher levels of anger and difficulties in finding fixed residence even six years later (Wickrama et al. 2012). Conversely, successfully entering into employment can have long-term positive consequences for the mental and physical health of the individuals, as well as their social and professional evolvement (Schulenberg et al. 2004).

Irrespective of situational factors, research suggests some personality traits predict how well graduates perform in their jobs. For example, Extraversion and Conscientiousness reliably predict transfer of skills from higher education to work, and also predict career success and salary (Abele and Spurk 2009; Eby et al. 2003; McManus et al. 2004; O’Reilly and Chatman 1994; Rode et al. 2008).

In addition to personality factors, motivation to find a job after graduation is linked to mental health. According to a 4-year longitudinal study from Germany (Haase et al. 2012) and a 2-year study from Finland (Nurmi et al. 2002), if a young person has clear and committed career goals and thus measures high on ‘goal engagement’, they are more likely to find a job and have robust wellbeing after university. However, for those who do not find a job and whose career does not progress well in the early years after university, goal engagement is likely to lead to depression. In other words, to really want a particular job makes rejection and failure that much harder.

The Challenge of Residential Status in the Post-university Transition

One of the challenges in forging a fully autonomous lifestyle after university is that about half of UK students either return to live with their parents or continue to do so (National Union of Students 2016). According to the traditional housing ladder model, the step following education was home-leaving, followed by renting and then eventually house ownership (Beer et al. 2011). However, that predictable sequence has now ceded to a more complex and non-linear set of pathways for young graduates and other young adults seeking independent living (Rugg et al. 2004). The instability in the graduate labour market and high property prices in the UK has created an obstacle towards the direct transition from university to employment and fully independent living arrangements (Bentley and McCallum 2019). Increasingly, graduates find themselves in jobs that do not provide sufficient income to live independently, and this is compounded by the burden of student debt and high property prices in both the rental and purchase market (Chevalier and Lindley 2009). This pattern of increasing numbers of graduates living with parents has also been found recently in the USA (Fry 2016).

Students and graduates can be influenced by parents through the provision of economic support and accommodation, and this can affect career decisions and emotional wellbeing, leading to a feeling of not being in control (Jones et al. 2006; Whiston and Keller 2004). It has been found that ‘helicopter parenting’ (parenting that is involved to the point of being overbearing) in tandem with perceived low parental warmth while at university is associated with lower self-worth and a greater extent of risk behaviours (Nelson et al. 2015). Furthermore, research suggests that living with parents after university can undermine a graduate’s sense of independence and autonomous identity (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1999), and has recently been shown to predict poor occupational attainment in graduates (Manzoni 2018).

Aims and Hypotheses

The aims of the current paper were to build on the research currently available on how eudaimonic wellbeing and depressive symptoms change over the course of the year after graduating from university, and how these relate to retrospective appraisals of personal crisis. To explore this, we followed a sample of graduates longitudinally for one year following graduation, assessing employment status, residential status, psychological wellbeing and depressive symptoms on three occasions at 6-month intervals. At the end of the 12 months, we asked participants if they had experienced the past year as a time of crisis. Based on the aforementioned studies on crises in young adults, our first hypothesis was that the group of individuals reporting a crisis, compared with the group who did not report a crisis, would express lower levels of eudaimonic wellbeing and higher levels of depression at all time points, when controlling for relevant covariates. In addition, we set an exploratory goal to establish which facets of psychological wellbeing were associated with crisis. Our second hypothesis, based on the past research on residential status in young adults, was that depression levels would be higher, wellbeing levels lower, and crises more likely in graduates who were living with their parents, in comparison with those who were not living with parents.

Method

Design

The study employed a repeated-measures three-phase longitudinal design that lasted 12 months. The first phase took place 1 month after the individuals involved had completed their university studies. The second phase took place 6 months after that. The third phase occurred a further 6 months later.

Participants

Participants were students from a university in London who had just completed their undergraduate studies and were not intending to go into postgraduate study over the following year. Participants were invited from all departments across the university, and the eventual subject distribution across the university’s formal subject groupings was: Science (5.6%), Architecture, Design and Construction (5.6%), Humanities and Social Sciences (22.8%), Business (23.3%), Computing and Mathematical Sciences (12.8%), Education (7.8%), Health and Social Care (17.8%). The full number of individuals invited via email is not known precisely as student group email lists were used; however, it is approximated at 1500. In Phase 1, there were 240 participants; in Phase 2, 188 participants, and in Phase 3 185 participants, showing a completion rate of 77%. Of the final 185 completers, the sex ratio was 80% female, 20% male. The ethnic mix was as follows: 55% White British, 12% White other, 9% Black, 16% Asian, 3% Chinese, 6% Mixed ethnicity, 6% other. The mean age of the final sample was 24, with a range of 20 to 48. 90.4% of the sample were aged 30 or under. We conducted analysis on complete cases only given that the majority of missing data represented participants who only completed one phase. There were no demographic or outcome-based differences between completers and non-completers.

Measures

Wellbeing: PWB 18-Item Version (Ryff and Keyes 1995)

The Psychological Wellbeing Scales (PWB) assess six aspects of eudaimonic wellbeing. These scales, along with an indicative item from each, are: Purpose in Life (“I don’t have a good sense of what it is I'm trying to accomplish in life”), Personal Growth (“For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth”), Environmental Mastery (“The demands of everyday life often get me down”), Positive Relationships (“People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others”), Autonomy (“I have confidence in my own opinions, even if they are different from the way most other people think”) and Self-Acceptance (“When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out so far”). Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert Scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). The 18-item version was used in this study. Cronbach’s α for the subscales in the current sample ranged from α = 0.59 to 0.67.

Depressive Symptoms: CESD-10 (Zhang et al. 2012)

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the CESD-10. This is a 10-item scale for non-clinical populations that assesses feelings over the past week. Example items are “I felt lonely” and “I felt depressed”. Answers are given on a four-point scale: Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day); Some or a little of the time (1–2 days); Occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days); All of the time (5–7 days). The sum of answers to the 10 items is used as a numerical indicator of depressive symptomology. A score of 10 or more is indicative of mild depression. Cronbach’s α for the current sample was α = 0.73.

CDQ Crisis Definition-Question (Robinson 2019)

The appraisal of developmental crisis was assessed using the retrospective version of the Crisis Definition and Question (CDQ; Robinson and Wright 2013; Robinson et al. 2017). The definition that is presented was developed based on a series of in-depth qualitative studies on developmental crises in younger and older adults (Robinson and Smith 2010; Robinson and Stell 2015), along with a literature review on definitions of developmental crisis (Robinson and Wright 2013). The standard definition describes the typical duration of a crisis as several years, but to fit with the 1-year longitudinal study the wording was adapted to point to a typical minimum duration, i.e. lasting 6 months or more. The following definition of developmental crisis was first presented to participants: “A crisis is a time in your life during which your emotions were more negative and unstable than normal, and you experienced changes and transitions that challenged your capacity to cope with stress, making you feel at times overwhelmed. During a crisis people often question things, including their goals, values and sense of identity. Typically crises last six months or more.”

In the 12-month after university phase, participants were provided with this definition and then the following question was presented: “Do you feel that you have been through a crisis since leaving university?” to which they were required to respond using a binary forced-choice—yes or no.

Residential Status

Residential status was assessed using a single item at all three time points, phrased as follows: please state your residential status at the current time: Living with friends; Living with parents or a parent; Living with partner/spouse; Living as a lodger; Living with other relatives; Living on your own; Other.

Work Status

Work status was assessed using a single item at all three time points, with the following seven response options: Unemployed; Job secured but not started yet; In postgraduate education; Part-time paid employment; Full-time paid employment; Part-time voluntary employment; Full-time voluntary employment. For the purposes of creating a two-level variable for analysis purposes, response options were re-coded into of ‘in paid employment’ (job secured but not started yet, full-time and part-time paid employment) vs ‘not in paid employment’ (unemployed, in voluntary employment).

Procedure

Questionnaires were completed online. Participants were sent links to questionnaires via email at the allocated time and asked to complete them within one month of receiving the email. Participants who completed all three phases of the research received a £20 shopping voucher as a reward.

Statistical Analysis Plan

Our first aim of exploring the trajectory of depressive symptoms (CESD-10) and psychological wellbeing (PWB) across crisis vs. no crisis groups during the 12-month post-University transition period, was examined with a multilevel growth model. Fixed effects were time (level 1), crisis event (level 2: a participant level variable) and a Time × Crisis cross-level interaction term. We additionally included living with parents (yes/no) and employment status (not in paid employment/in paid employment) as time-varying covariates and sex (male/female) as a level 2 time-invariant between-persons covariate to explore whether they represented additional influences on depression/wellbeing. If no significant effect of time emerged, we tested for a quadratic effect of time by squaring the centred value of time (see below) and including this as an additional fixed effect term.

We modelled participants as a level 2 variable and estimated random coefficients for the intercept and time slope. These random coefficients provide an estimate of how much individual participant variation exists in wellbeing/depression scores (i.e. the intercept) and the trajectories (i.e. the time slope) of wellbeing/depression. The latter is particularly valuable for assessing whether any changes in mean wellbeing/depression across time are accompanied by significant variation in individual trajectories.

Prior to analysis, time was centred (at month 6) to avoid multicollinearity with the Time × Crisis term. Significance values for individual fixed effects were assessed against a t distribution and random effects were assessed with likelihood ratio tests (Hox et al. 2017). All multilevel analysis was performed using the nlme packages in R (Pinheiro et al. 2019), with full maximum likelihood used to estimate model parameters.

To examine our second hypothesis that crises were more likely to occur in graduates living with their parents, we conducted χ2 tests with variables of living with parents (yes/no) and crisis (yes/no) at each of the three phases.

Results

Given that we are testing two hypotheses simultaneously, the required value for ascertaining significance was reduced to p < 0.025, according to the Bonferroni correction process.

With regards to the prevalence of reported crisis, out of the 185 individuals who completed the longitudinal study, 61 individuals (33%) reported experiencing a crisis during the year. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics showing work status data and living at home data for each phase of the study.

Depressive Symptoms (CESD-10)

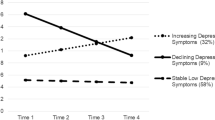

As can be seen from the results of the multilevel model analysis in Table 2, there was a significant effect of crisis (p < 0.001), with those reporting a crisis event scoring 3.03 points higher on the CESD-10 (indicating greater depressive symptomology) than those who did not report a crisis. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the time trajectory of depressive symptoms did not appear to vary overall or within crisis groups, with no main or interactive effects of time observed. The addition of a quadratic term for time demonstrated no significant effect (p = 0.693), suggesting no evidence for a non-linear effect of time over the periods assessed. Random coefficients also suggested no significant variation in individual participant time trajectories of depressive symptoms (LRT = 0.47, p = 0.789).

Results also indicated a significant effect of residing with parents (p = 0.017), with the mean depression score 1.45 points higher when participants reported living with parents. Finally, a significant effect of employment status was found, with depression scores 1.31 points higher when participants reported not being in paid employment.

Psychological Wellbeing

As can be seen in Table 3 and Fig. 2, there was a significant effect of crisis on wellbeing, with overall wellbeing scores lower for those who reported the occurrence of a crisis by 0.31 points compared to those who did not (p = 0.001). No overall change in mean wellbeing across time (p = 0.618) was observed, and there was no significant variation in individual participant trajectories of wellbeing (LRT = 2.26, p = 0.322). The addition of a quadratic term for time also demonstrated no significant effect (p = 0.716).

In line with our hypotheses to identify which specific components of wellbeing that may be affected by crisis, we reran the multilevel analysis on each wellbeing dimensions after removing non-significant predictors. Results found consistently lower scores for crisis on all facets of wellbeing as follows, with the regression coefficient B indicating the difference in scores for crisis vs. no crisis groups: Environmental Mastery (B = − 0.51, p < 0.001), Positive Relationships (B = − 0.22, p = 0.091), Personal Growth (B = − 0.16, p = 0.068), Autonomy (B = − 0.26, p = 0.038), Purpose in Life (B = − 0.26, p = 0.043), Self-Acceptance (B = − 0.34, p = 0.023). Only two of these facets, Environmental Mastery and Self-Acceptance, were significant at the corrected level of p < 0.025.

To test the relative frequency of crises across the living with parents and not living with parents groups, three χ2 test were conducted; for all, the two-level categorical variables of crisis vs non-crisis was entered, and for each one living with parents and not living with parents was entered for one of the three phases. There was no relationship found between crisis and residential status in any of the three phases.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to establish how, over the 12-month period following departure from university, reports of developmental crisis relate to wellbeing and depressive symptoms in graduates, and also whether living with one’s parents after leaving university relates to negative wellbeing over this time period. We hypothesized that the presence of a developmental crisis would predict low wellbeing and depression—this hypothesis was partially supported, insofar as both depression and one facet of wellbeing (environmental mastery) were strongly related to crisis appraisals. We also predicted that living with parents would relate to low wellbeing and depression. This hypothesis was also partially supported; in the first phase after leaving university, living with parents is related to low levels self-acceptance. In the second and third wave, it is related to a sense of low purpose in life, depression, and in the third wave only, it is strongly related to low autonomy. Time itself during the 12-month period showed little effect on wellbeing; in our statistical models, there were no significant within-subjects effects of time; this is illustrated by the fact that in Figs. 1 and 2, in which time is presented along the x-axis, all lines show a flat, or nearly flat, gradient.

With regards to the group that retrospectively self-defined as going through a developmental crisis in the year after leaving university; there is little by way of precedent for ascertaining whether this prevalence of 33% is high or low, other than the study by Robinson and Wright (2013), which also used the CDQ. In that study, 45% of adults aged 30+ reported having been through a developmental crisis at some point between ages 20 and 29. Extrapolating from this previous finding, the fact that 33% retrospectively reported a crisis in one particular year is very high. We therefore surmise that the post-university transition is a relatively crisis-prone period. This fits with the findings summarized in the introduction of this article, which portray the post-university transition as one that is a complex and demanding life transition that contains notable potential for stress and identity challenges (Crebert et al. 2004; Johnson 1991).

With regards to crisis and wellbeing there was some evidence to suggest that the strongest effects may be evident for Environmental Mastery, although further research would be needed to confirm this. Of all the wellbeing subscales, this is the most externally focused one; it focuses on issues of managing responsibilities, employing constructive goal-directed action and keeping on top of tasks and demands. Low levels on this wellbeing subscale represent a feeling of being unable to keep a sense of healthy control over the external features of life. This in turn fits with the locked-out form of quarter-life crisis, which has been found to be one that is common in the transition out of education into work (Robinson 2019).

Ryff and Keyes (1995) found that Environmental Mastery is higher in midlife adults than young adults, suggesting a normative upward developmental trajectory. It may be that it is precisely the difficulties of taking control over life that graduates face, rather intensively, that explains why environmental mastery is generally lower in young adult individuals relative to older adults.

When we examined wellbeing in the groups of graduates who were living with their parents, compared to those who were not, we found that graduates who were living with parents were overall more depressed. The same was true of graduates who were unemployed—they had higher ratings of depression than those in paid work. Causality may be working in either or both directions; it may be that individuals who struggle with depression and cultivating a clear sense of purpose or autonomy are more likely to live with parents after university and remain unemployed, but it also likely that living with parents and being without paid work induces a sense of feeling down and purposeless, when young adults who find themselves living in the family home, and compare themselves negatively against their peers who have residential and financial autonomy. This finding is salient as a topic of future research because there are increasing numbers of graduates moving back, or continuing to live with parents (Dickler 2016). This in turn reflects a wider societal trend; the proportion of people aged 20 to 34 who live with their parents has risen from 19.48% in 1997, equating to 2.4 million people, to 25.91% in 2017, equating to 3.4 million (Mohdin 2019). There is a marked lack of research exploring the relationship between living with parents after leaving university and wellbeing or mental health, but what little exists supports the notion that living with parents may be a causal factor in low wellbeing among graduates (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1999; Robinson 2019).

This study of participants within a single university is designed to act as a pilot study for future studies conducted across multiple universities and potentially across different countries. The study has a number of limitations, all of which point towards ways of conducting future studies in this area. Firstly, due to logistical limitations in terms of when the study could viably start, we did not collect data from graduates before they left university and so have no pre-transition baseline variable against which to compare the three phases of post-university data. It would be ideal, in future longitudinal studies, to collect at least one phase while participants were still at university, followed by multiple phases after leaving university. A methodological ideal would be to follow students through their whole studying journey, and then continue to study them after they leave. The sample that we achieved was predominantly female, which is likely to be a product of a differential participation motivation between males and females in the sample universe. The high proportion of females could have influenced the data in the direction of higher depression and crisis rates, given that there is a robust sex difference on both these variables (Robinson and Wright 2013). Future research could aim at a purposively stratified sample in which males and females are intentionally sampled to similar numbers. The purely random sampling approach, as achieved here, was beholden to take all those who offered to participate. It is also important to consider that the economic and social circumstances of graduates differ by country, so that generalization of the findings to other UK establishments is more justifiable than to other countries.

In terms of how crisis was assessed, we used a modified structured-autobiographical question that was developed for the purpose of assessing developmental crisis episodes in adults. We used this retrospective, single assessment appraisal of crisis vs. no crisis as an independent variable in a multilevel analysis, which necessarily precludes attributions of causal direction (Northcott 2008). It would be appropriate in the future to assess crisis using a screening instrument at all phases of the study, to explore whether the appraisal of crisis is one that evolves over the period of study, and how that relates to a later retrospective appraisal. A further issue to take into account is that crisis and wellbeing overlap as constructs in terms of their defining features, and that relationships between the two may be, in part, a function of this construct overlap. The first author is currently in the process of developing a multi-item Likert scale-based psychometric measure of crisis, the discriminant and convergent validity of which will be established. This will have a number of benefits over the vignette-based self-appraisal approach used here, including the elicitation of continuous rather than categorical data, and will be used in future studies of crises and wellbeing in graduates.

A further limitation of the study is that we do not have data from an age-matched control of non-graduates, to explore whether what we have found by way of crisis prevalence, crisis features and the effects of living with parents would be different in this comparison sample. We strongly recommend to researchers to investigate this area using forms of data analysis that assess within-person change, such as latent growth modelling or multilevel modelling.

The implications for HE institutions of our findings, if replicated in further studies, are considerable. A full third of graduates in our sample reported experiencing a developmental crisis, and this manifested in a sense of feeling out of control and depressed. Living with parents after graduation may be a situation that compounds this challenge, given that it is associated with low self-acceptance, low purpose and low autonomy. Interventions to support students prepare for the psychological challenges of the post-university transition must be an important next step, along with research to evaluate their effectiveness longitudinally. Indeed, it could be argued that HE has done negligibly little at all to make students aware of the psychosocial challenges that the transition out of university brings and to help them prepare for this. We envisage a systematically designed and delivered brief course of workshops to imminent graduates to help them prepare for the challenges ahead, which eventually becomes standard delivery across HE institutions. It is our aim to develop such a course, provisionally entitled the PLUS course (Preparing for Leaving University and Study), and to evaluate it in subsequent research studies.

References

Abele, A. E., & Spurk, D. (2009). The longitudinal impact of self-efficacy and career goals on objective and subjective career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.10.005.

Arnett, J. J. (2000a). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. (2016). College students as emerging adults: The developmental implications of the college context. Emerging Adulthood, 4, 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815587422.

Bathmaker, A. M. (2003). The Expansion of Higher Education: A consideration of control, funding and quality. In S. Bartlett & D. Burton (Eds) Education studies. Essential issues (pp 169–189). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446215043.

Bentley, D., & McCallum, A. (2019). Rise and Fall: The shift in household growth rates since the 1990s. Civitas. https://www.civitas.org.uk/content/files/riseandfalltheshiftinhouseholdgrowthratessincethe1990s.pdf.

Candy, P., & Crebert, R. (1991). Ivory Tower to Concrete Jungle: The difficult transition from the academy to the workplace as learning environments. The Journal of Higher Education, 62(5), 570–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1991.11774153.

Chang, E., & Hancock, K. (2003). Role stress and role ambiguity in new nursing graduates in Australia. Nursing and Health Sciences, 5(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00147.x.

CIPD. (2017). The graduate employment gap: Expectations versus reality. Retrieved April 10, 2019, from https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/work/skills/graduate-employment-gap-report.

Crebert, G., Bates, M., Bell, B., Patrick, C., & Cragnolini, V. (2004). Ivory Tower to Concrete Jungle revisited. Journal of Education and Work, 17(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363908042000174192.

Crafter, S., & Maunder, R. (2012). Understanding transitions using a sociocultural framework. Educational and Child Psychology, 29, 10–18.

Beer, A., Faulkner, D., Paris, C., & Clower, T. (2011). Housing transitions through the life course aspirations, needs and policy. Bristol: Policy Press.

Chevalier, A., & Lindley, J. (2009). Overeducation and the skills of UK graduates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 172(2), 307–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00578.x.

Cooke, R., Barkham, M., Audin, K., Bradley, M., & Davy, J. (2004). Student debt and its relation to student mental health. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 28(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877032000161814.

Dickler, J. (2016). More college grads move back home with mom and dad. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2016/06/10/more-college-grads-move-back-home-with-mom-and-dad.html.

Eby, L., Butts, M., & Lockwood, A. (2003). Predictors of success in the era of the boundaryless career. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(6), 689–708. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.214.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. London: Faber and Faber.

Feather, N., & Bond, M. (1983). Time structure and purposeful activity among employed and unemployed university graduates. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 56(3), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1983.tb00131.x.

Fry, R. (2016). For first time in modern era, living with parents edges out other living arrangements for 18- to 34-year-olds.https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/05/24/for-first-time-in-modern-era-living-with-parents-edges-out-other-living-arrangements-for-18-to-34-year-olds/.

Goldscheider, F., & Goldscheider, C. (1999). The changing transition to adulthood: Leaving and returning home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Haase, C., Heckhausen, J., & Silbereisen, R. (2012). The interplay of occupational motivation and well-being during the transition from university to work. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1739–1751. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026641.

Hill, C. (2012). Why the job market is even tougher for mature graduates. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/careers/careers-blog/job-seeking-overqualified-mature-graduates.

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315650982.

Johnson, D. (1991). Stress among graduates working in the SME sector. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 6(5), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683949110137592.

Jones, G., O’Sullivan, A., & Rouse, J. (2006). Young adults, partners and parents: Individual agency and the problems of support. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(4), 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600914374.

Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Stress and Emotion: a new synthesis. London: Free Association Books.

Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Ballantine Books.

Levinson, D. J. (1996). The seasons of a woman’s life. New York: Ballantine Books.

Manzoni, A. (2018). Parental support and youth occupational attainment: Help or hindrance? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1580–1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0856-z.

Mcmanus, I., Keeling, A., & Paice, E. (2004). Stress, burnout and doctors’ attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: A twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Medicine, 2, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-29.

Mohdin, A. (2019). Nearly a million more young adults now live with parents – study. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/08/million-more-young-adults-live-parents-uk-housing.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nielson, M. G. (2015). Is hovering smothering or loving? An examination of parental warmth as a moderator of relations between helicopter parenting and emerging adults’ indices of adjustment. Emerging Adulthood, 3(4), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815576458.

Northcott, R. (2008). Can ANOVA measure causal strength? The Quarterly Review of Biology, 83(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/529562.

Nurmi, J., Salmela-Aro, K., & Koivisto, P. (2002). Goal importance and related achievement beliefs and emotions during the transition from vocational school to work: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1866.

National Union of Students. (2016). Double jeopardy: Assessing the dual impact of student debt and graduate outcomes on the first £9K fee paying graduates. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/resources/double-jeopardy.

O’Connor, D., & Wolfe, D. (1991). From crisis to growth at midlife: Changes in personal paradigm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12(4), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030120407.

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D., & R Core Team (2019). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-140. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

O’Reilly, C., & Chatman, J. (1994). Working smarter and harder: A longitudinal study of managerial success. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(4), 603–627. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393773.

Pollard, E., Pearson, R., & Willison, R. (2004). Next choices: Career choices beyond university. Report 405. Institute of Employment Studies.

Purcell, K., & Elias, P. (2004). Seven years on: Graduate careers in a changing labour market. The Higher Education Careers Services Unit #.

Robinson, O. C. (2013). Development through adulthood: An integrative sourcebook. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Robinson, O. C. (2016). Emerging adulthood, early adulthood and quarter-life crisis: Updating Erikson for the twenty-first century. In R. Žukauskiene (Ed.), Emerging adulthood in a European context (pp. 17–30). Abingdon: Routledge.

Robinson, O. (2019). A longitudinal mixed-methods case study of quarter-life crisis during the post-university transition: Locked-out and locked-in forms in combination. Emerging Adulthood, 7(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818764144.

Robinson, O., Demetre, J., & Litman, J. (2017). Adult life stage and crisis as predictors of curiosity and authenticity: Testing inferences from Erikson’s lifespan theory. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(3), 426–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416645201.

Robinson, O., & Smith, J. (2010). Investigating the form and dynamics of crisis episodes in early adulthood: The application of a composite qualitative method. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802699084.

Robinson, O., & Stell, A. (2015). Later-life crisis: Towards a holistic model. Journal of Adult Development, 22(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9199-5.

Robinson, O., & Wright, G. (2013). The prevalence, types and perceived outcomes of crisis episodes in early adulthood and midlife: A structured retrospective-autobiographical study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(5), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413492464.

Rode, J., Arthaud-Day, M., Mooney, C., Near, J., & Baldwin, T. (2008). Ability and personality predictors of salary, perceived job success, and perceived career success in the initial career stage (report). International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 16(3), 292–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2008.00435.x.

Rugg, J., Ford, J., & Burrows, R. (2004). Housing advantage? The role of student renting in the constitution of housing biographies in the United Kingdom. Journal of Youth Studies, 7(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367626042000209930.

Ryan, P. (2001). The school-to-work transition: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(1), 34–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.39.1.34.

Ryff, C., & Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

Schulenberg, J. E., Bryant, A. L., & O’Malley, P. M. (2004). Taking hold of some kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1119–1140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404040167.

Slaikeu, K. A. (1990). Crisis intervention—A handbook for practice and research (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Whiston, S., & Keller, B. (2004). The influences of the family of origin on career development: A review and analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 32(4), 493–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000004265660.

Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., & Martin, M. (2012). Continuity and discontinuity of depressed mood from late adolescence to young adulthood: The mediating and stabilizing roles of young adults’ socioeconomic attainment. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 648–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.014.

Woodfield, R. (2011). Age and first destination employment from UK universities: Are mature students disadvantaged? Studies in Higher Education, 36(4), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075071003642431.

Zhang, W., O’Brien, N., Forrest, J. I., Salters, K. A., Patterson, T. L., et al. (2012). Validating a Shortened Depression Scale (10 Item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e40793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040793.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Robinson, O.C., Cimporescu, M. & Thompson, T. Wellbeing, Developmental Crisis and Residential Status in the Year After Graduating from Higher Education: A 12-Month Longitudinal Study. J Adult Dev 28, 138–148 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-020-09361-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-020-09361-1