Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health measures have adversely affected the lives of people worldwide, raising concern over the pandemic's mental health consequences. Guided by a systemic model of family functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic (Prime et al., 2020), the current study aimed to examine how caregiver well-being (i.e., maternal depressive symptoms) and family organization (i.e., household chaos) are related to longitudinal trajectories of children's emotional and behavioral problems. Data were collected at four time points during and after home lockdown periods. Mothers of children (N = 230; 55% male) between the ages of two to five years were asked to complete questionnaires via an Israeli online research platform. Results indicated that emotional and behavioral problems, household chaos, and maternal depressive symptoms were the highest during the first lockdown assessment and dropped in the post-lockdown periods. Multilevel models further revealed that at the between-participants level, maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos positively predicted children's emotional and behavioral problems. At the within-participants level, household chaos fluctuations positively predicted fluctuations in child behavioral but not emotional problems. Our findings suggest that lockdowns have adverse effects on both maternal and child mental health. Screening for depressive symptoms among mothers of young children and maintaining household structure are important targets for future interventions to assist parents in navigating the multiple challenges brought upon by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted individuals' daily lives worldwide (Torales et al., 2020). There is some evidence of increased mental health problems in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period (Li et al., 2021; Pierce et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020). However, some individuals are disproportionately affected, suffering from heightened stress levels compared to others. In addition to overall pandemic stressors, such as financial insecurity and remote work, parents of young children face a unique set of stressors such as caregiving burden and the need to balance between work demands and caregiving duties during periods of childcare closure (Prime et al., 2020). This is compounded by the fact that young children have a limited ability to self-regulate their emotions and behavior and rely mainly on external regulation provided by their caregivers, especially in times of stress and uncertainty (Bariola et al., 2011; Kiel & Kalomiris, 2015; Sameroff, 2009; Spinrad et al., 2004). The COVID-19 pandemic can act as a test case of how prolonged stress that is external to the family context but impacts it tremendously, through unique changes to the home environment can affect children's mental health. Specifically, it allows us to examine how these externally induced changes affect parents' mental health and household chaos, which reflect central aspects of family functioning and children's mental well-being. Prime et al. (2020) proposed a systemic model of family functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic, which emphasizes child, parent, and family factors in adjusting to the pandemic over time. The current study examined these multilevel effects longitudinally to understand how they relate to specific changes brought on by oscillations between lockdowns and their aftermath.

Child Emotional and Behavioral Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Many studies examined the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children's well-being during this unprecedented time of acute stress and social isolation. Some have raised concerns about the effect of home confinement and quarantines on children's mental health (Phelps & Sperry, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The majority of research focused on a wide range of ages or middle childhood and adolescence. Overall, these studies have reported a rise in children's mental health problems between the pre-pandemic period and the first lockdown (Jiao et al., 2020; Panda et al., 2021; Patrick et al., 2020; Spinelli et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020; Yeasmin et al., 2020). Less is known about younger ages and how these changes relate to the specific aspects of the family environment. The extant research shows that the pandemic adversely affected younger children and that the family environment is an essential factor in this change. For example, one study found an association between the impact of COVID-19 on the family unit (e.g., job loss, health worries) and child behavior problems (Foley et al., 2021). Two studies on preschool children found higher scores for behavioral problems than other pre-pandemic samples and decreased emotional and behavioral functioning between the pre-pandemic period and three weeks after lockdown (Glynn et al., 2021; Specht et al., 2021). Another study found increased children's hyperactivity and conduct problems between the pre-pandemic period and April 2020, but no change was found for emotional problems (Romero et al., 2020). Thus, there is evidence of increased behavioral and emotional difficulties in children since the COVID-19 outbreak. Still, extant literature focused on single time points during the pandemic and did not consider changes over time as the pandemic unfolded. This can only be done using longitudinal research designs, which can uncover mechanistic effects and examine trajectories of change over time (Prime et al., 2020). Furthermore, as the pandemic unfolds in a non-linear way (reflecting its unpredictability), it is necessary to examine how these changes in the pandemic relate to specific occurrences (e.g., lockdowns, family-isolation, COVID-19 outburst) during the pandemic, not only overall changes over time. Specifically, the institution of lockdowns represents a major event with far-reaching consequences on families' daily functioning and therefore deserves specific attention.

Environmental Factors

Prime et al. (2020) suggest that proximal and distal environmental factors, such as social disruption and caregiver well-being, can shape children's emotional and behavioral adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. In early childhood, children rely mainly on external regulation provided by their caregivers to regulate their emotions and behavior (Sameroff, 2010). The COVID-19 lockdown periods represent atypical circumstances in which children were not exposed to any other caregiving figures (e.g., teachers, extended family) besides their parents, who were the sole providers of children's physical, emotional and educational needs (Russell et al., 2020). Under these conditions, we hypothesized that parental well-being and the organization of the home environment would be key factors in shaping children's behavioral adjustment. We specifically focused on these two proximal factors based on previous research highlighting the significant impact that maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos can have on children's adjustment, and specifically on conduct and emotional problems (Coldwell et al., 2006; Marsh et al., 2020; Rohanachandra et al., 2018; Yamada et al., 2021; Zhang, 2022).

Household Chaos

Household chaos refers to the degree of disorganization in the home environment manifested by high noise, distractions, and a lack of consistent daily routines (Wachs & Evans, 2010). Household chaos is associated with less optimal socio-emotional development, including higher rates of behavioral problems and internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression (Coldwell et al., 2006; Deater-Deckard et al., 2009; Dumas et al., 2005; Evans & Wachs, 2010; Gregory et al., 2005; Hannigan et al., 2017; Marsh et al., 2020). The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has forced many families to readjust their lives in response to the social distancing and home lockdown regulations. For some families, these changes may have resulted in chaos or lack of control, which may negatively affect children's well-being. For example, higher levels of household chaos during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy were associated with higher child negativity and less effective child emotion regulation (Spinelli et al., 2020).

Similarly, a multi-site international study found that increased levels of household chaos were concurrently associated with higher levels of child problem behaviors, specifically, conduct problems, and to a lesser degree with emotion or peer problems (Foley et al., 2021). Cassinat et al. (2021) found that higher chaos levels predicted less positive family relationships in families with adolescents. However, the cross-sectional nature of these studies does not enable to draw a causal conclusion. The associations between household chaos and children's behavioral problems may be bidirectional (Johnson et al., 2021), as children with elevated behavioral problems may elicit high levels of household chaos.

Maternal Depressive Symptoms

Although work-family balance has changed dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic for all parents, mothers still serve as primary caregivers in most households (Feng & Savani, 2020; Shockley et al., 2021; Zoch et al., 2021), and caregiving duties increased tremendously during the pandemic (Power, 2020). This situation in which mothers are obligated to balance caregiving and work demands may lead to mental health problems and parental burnout (Griffith, 2020). Indeed, several studies found elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms in parents since the COVID-19 outbreak (Davidson et al., 2021; Patrick et al., 2020; Racine et al., 2021).

Research conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic consistently shows that maternal depressive symptoms (MDS) are associated with various adverse child outcomes, such as behavior problems (Goodman et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2011), emotional difficulties (Cutrona & Troutman, 1986; Hoffman et al., 2006) and poor cognitive functioning (Grace et al., 2003). Maternal depression was found to be related to children's outcomes through different mechanisms (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999) like heritability, exposure to maternal maladaptive behaviors and affect, and exposure to stressful life events (Kiernan & Huerta, 2008; Lovejoy et al., 2000; Priel et al., 2020). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, recent studies found associations between familial difficulties caused by the pandemic, parental stress and children's behavioral and emotional problems (Foley et al., 2021; Spinelli et al., 2020). For example, parental distress increases the risk of children exhibiting more behavioral and emotional problems (Marchetti et al., 2020; Tso et al., 2020). More specifically, elevated maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms were associated with increases in children's emotional and behavioral problems from the pre-pandemic period to the first lockdown (Frigerio et al., 2022). However, a major limitation of the extant literature is the reliance on either cross-sectional or two-timepoint data (before the pandemic and during the first lockdown). These research designs do not enable the examination of change over time in family and child functioning and do not characterize how specific conditions (i.e., lockdown regulations) are related to these changes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to apply a repeated measures longitudinal design to address these questions.

The Present Study

In March 2020, home confinement regulations were implemented in Israel for the first time, including national daycare and school closures, lockdown laws, and social-distancing recommendations. These regulations were gradually amended with the decrease in infection rates, and schools and childcare centers reopened in May 2020, but some restrictions remained, emphasizing social distancing. Since then, two additional lockdown periods were implemented in September 2020 and at the end of January 2021. Following the third lockdown, all social distancing regulations were eliminated, and schools reopened at full capacity. These defined periods of home lockdowns provided us a unique opportunity to examine predictors and changes in young children's adjustment during and after the lockdown periods and differentiated between-individual variation (i.e., within-person effects) and differences in patterns between individuals (i.e., between-person effects). Accordingly, our first aim was to investigate how children's emotional and behavioral problems, maternal depressive symptoms, and household chaos relate to transitions between lockdowns and relative routine during the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that children's emotional and behavioral problems, maternal depressive symptoms, and household chaos would increase during lockdowns and decrease after lockdowns. Our second aim was to explore household chaos and maternal depressive symptoms as predictors of children's emotional and behavioral problems. We hypothesized that elevated maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos across time points would positively predict children's emotional and behavioral problems (between-subject effect). Moreover, we hypothesized that fluctuations in maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos would predict changes in children's emotional and behavioral problems (within-person effect). That is, the extent to which a particular time point is characterized by greater maternal depressive symptoms or household chaos levels as compared to average levels will predict greater change in children's emotional and behavioral problems.

Methods

Sampling and Participants

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Research Committee at Ben-Gurion University. Data were collected between September 2020 and March 2021. The current study is part of a larger research project conducted through The Midgam Project Web Panel (MIDGAM), an online Israeli research platform. This online Israeli research platform has access to a sample of approximately 100,000 panelists that participate in different online studies for a fee (http://www.midgampanel.com/research/en/index.asp). The MIDGAM platform approached 1705 potential participants that fit the inclusion criteria (i.e., Mothers of children between the ages of two to five years). A total of 383 entered the survey, and 304 participated and completed the study. During the first home confinement (March 2020), mothers were asked to choose one child within the age range of two to five years and complete questionnaires that assessed child behavior problems, household chaos, and demographic information (maternal depressive symptoms were collected from the second lockdown). Mothers were asked to complete the questionnaire for the same target child at all time points. To verify that mothers referred to the same target child at each time point, we asked mothers to state the child's initials and age at each time point.

Overall, a total of 230 participants were used in the analyses. A total of 285 participants completed at least one assessment in the current study, from a pool of 304 participants who responded to the questionnaires at previous time points. Of those, fifty-five were excluded from the study due to: child health and developmental problems (n = 5), severe maternal health problems (n = 2), children who started first grade during the study, as this constitutes a major change in the childcare environment (n = 21), and having valid data at only one time point in the current study (n = 27). Additional 44 responses were excluded at specific time points due to mothers completing the questionnaire for a different target child than the other time points, as indicated by different child initials and ages (n = 26) or wrongly answering the attention verifying items (n = 18). The final sample size was 204 at T0, 205 at T1, 176 at T2, 222 at T3, and 184 at T4. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all demographic variables.

We used data collected at five time points (see Table 2). During March 2020 (i.e., Israel's first lockdown), mothers were also asked to answer several questionnaires, including retrospective reports about children’s conduct and emotional problems in the two months before the COVID-19 outbreak in Israel (T0). Data on additional main study variables (i.e., maternal depressive symptoms) were not collected during this time point. Therefore, we only used the retrospective reports about children's pre-COVID behavior from this time point, and our research questions and main analyses focus on the second and third lockdown. T1 data were collected in September 2020, during Israel's second home lockdown. Data at T2 were collected during October 2020, at the end of the second lockdown period in Israel, after childcare was reopened. Data at T3 were collected during January 2021, the third lockdown period in Israel. Finally, data at T4 were collected during March 2021, one month after the home confinement regulations were amended and childcare systems reopened.

Measures

Child Emotional and Behavioral Problems

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) was used to assess children's emotional and behavioral problems at all four time points. The SDQ contains 25 items, each of which was scored on a 3-point scale (0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat true, 2 = Certainly true). In the current study, we used two subscales from version A (which focuses on psychological attributes): conduct problems (5 items, e.g., "Often loses temper") and emotional problems (5 items, e.g., "Often unhappy, depressed or tearful"). Scale scores were generated by summing the items on each scale. Cronbach α coefficients ranged from 0.49 to.77 for conduct problems and 0.60 to 0.77 for emotional problems (see Table 3). Cutoff scores for abnormal behavior and emotional problems were calculated based on a 4-band categorization (Green et al., 2005). For two to four-year-old children, the cutoff scores for 'high' and 'very high' were four and above for emotional problems and five and above for behavioral problems. For five-year-olds, the cutoff scores for 'high' and 'very high' were five and above for the emotional problems, and four and above for behavioral problems (Goodman et al., 2000).

Household Chaos

Household chaos was assessed using the short version of the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (CHAOS; Matheny et al., 1995). Mothers were asked to indicate the degree to which they agreed with six statements describing different aspects of chaos in their home (e.g., "You can't hear yourself think in our home") on a scale of 5-point. One item ("There is usually a television turned on somewhere in our home") was omitted owing to low variability. Cronbach α coefficients ranged from 0.52 to 0.69. These values are consistent with previous reports (Chen et al., 2014, α = 0.65; Coldwell et al., 2006, α = 0.57) and are expected in scales with a few items (Cortina, 1993).

Maternal Depressive Symptoms

Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-10 (CES-D-10; Andersen et al., 1994). The CES-D-10 is a brief self-report measure for depressive symptoms over the past week (e.g., 'I felt lonely'). Each item is scored between 0 to 3 (0 = Rarely or none of the time to 3 = All of the time). Items were summed, with higher scores indicating proneness to higher degrees of depression (Cronbach α coefficients were 0.88 at all time points), with the suggested cutoff score being 15 and above (Björgvinsson et al., 2013).

Covariates

Family income and child's age were controlled for based on previous research showing associations between these variables and maternal depressive symptoms, household chaos, and children's emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., Crick & Zahn–Waxler, 2003; Dumas et al., 2005). Child biological sex was controlled following previous research showing that boys exhibit higher levels of behavior problems than girls (Gustafsson et al., 2017). Family income was reported as a six-point scale and was combined to create a dichotomous variable (0 = below average, 1 = average income, and above). Due to the wide age range in our sample (two to five years), child age was treated as a 4-level factor to be more informative and interpretable (1 – 24–35.9 months; 2 – 36–47.9 months; 3 – 48–59.9 months; 4 – > = 60 months).

Analytic Approach

Because of the hierarchical structure of our data (i.e., repeated time points within families), we used a series of 2-level (a within-family level and a between-family level) multilevel models (MLMs) which were fitted using restricted maximum likelihood (REML). The analyses used all available data (i.e., data from families who did not complete all the assessments were also included). We ran 'Little's missing completely at random (MCAR) test. The results of this test indicated there were no differences between families who completed all time points and families with missing data (Little's MCAR test: χ 2 (490) = 509.11, p = 0.266). Under the assumption of MCAR, MLMs accommodate for missing data in level-1, as they are fitted with ML\ REML methods which uses partial pooling for parameters estimation (see Hoffman, 2014). MLMs and Satterthwaite degrees of freedom were estimated using the 'lmerTest' package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) in the R software platform (Team, 2021).

Changes in Children's Emotional and Behavioral Problems, Maternal Depressive Symptoms, and Household Chaos

To examine trajectories of the main study variables across time points (hypotheses 1–2), we ran four 2-level growth MLMs, one for each variable. The following model was estimated for each outcome (i.e., child problems, maternal depressive symptoms, and chaos):

In this equation, Behavioral Problems\ Emotional Problems \ Maternal Depressive Symptoms \ Chaos within family j in time-point i was modeled as a function of this family's intercept (b0j), time (b1j), and a level-1 error term. To account for between-family variability, the intercept was allowed to vary at level 2. The time variable was treated as a 4-level factor (T1, T2, T3, T4), as we did not expect to find a linear pattern across time-points, but rather a non-linear change from one time-point to the next. Therefore, the examine the main effect of time (i.e., and not the effects of time dummy variables), an omnibus ANOVA-like F-test was extracted from the fitted MLMs. Pseudo R2s for time fixed effects were calculated following the method described in Hoffman (2014), using the equation: 1 – (growth model’s level-1 variance)/ (empty model’s level-1 variance). Planned pairwise contrasts with Tukey corrections and Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated using the 'emmeans' package (Length, 2020). Six contrasts were examined: the total change from the first to the last time-point (T1 – T4); two contrasts of within lockdowns change (T1 – T2; T3 – T4), between lockdowns change (T2 – T3), and comparisons of lockdowns beginnings (T1 – T3) and ends (T2 – T4).

Since behavioral and emotional problems may act differently depending on the child's biological sex (Keiley et al., 2000), we ran an additional set of growth MLMs in which child sex served as a moderator. Sex (a dichotomous variable: 0 – boy, 1 – girl) was entered at level 2, and the random intercept and the time effect were modeled (thus creating the cross-level Time X Sex interaction). Pseudo R2s for these interaction effects were calculated as the proportion of reduction in the residual variance compared to the original growth model (i.e., with no moderation effect).

Between and Within Effects of Household Chaos and Maternal Depressive Symptoms on Child's Problems

To test our third hypothesis regarding the effects of chaos and mothers' depressive symptoms on children's emotional and behavioral problems, two additional MLMs were estimated (one for each outcome). Models included the between-family and within-family effects of the two main predictors (chaos\ depressive symptoms) and the control variables: child sex, child age, and family income. We also controlled for the lagged outcome within-family (the outcome from the previous time point centered to the family average). For observation from time i, the within-family deviation in a child's behavioral\ emotional problems from time i-1, was entered into the model. This enabled us to test the hypotheses above and beyond within-family fluctuations in child's problems. For T1's lagged outcome (i.e., pre T1), we used pre-COVID retrospective reports (T0) of child emotional and conduct problems that were assessed at the beginning of the study.

The generic models' equations were as follows:

Level 1:

Level 2:

In these equations, Child-Problems (emotional/ conduct) for family j in time-point i, were modeled at level 1 as a function of this family's intercept (b0j), within – mother j's deviation in depressive symptoms at a specific time-point (b1j), within – family j's deviation in chaos at a specific time-point (b1j), and the lagged deviance from Child-problems (b3j) plus a residual term quantifying the specific time-point deviation (eij). At level 2, Child-Problems within a specific family (b0j) were modeled as a function of the family's mean problems above time-points (γ00), mother j's deviance from the sample mean depressive symptoms levels (γ01), family j's deviance from the sample mean chaos levels (γ02), and the covariates child sex, age, and SES (γ03, γ04, γ05). To account for between-family variability, all level 1 effects were allowed to vary at level 2 (i.e., treated as random effects). The final models included only random effects that improved model fit (as determined by the deviance test; Hoffman, 2014, Chapter 3).

The level 1 within-family variables were centered around each family’s individual mean, and the level 2 between-family variables were centered around the sample mean. Both child sex and family income binary variables were centered around zero (Child sex: boys – 0.5 and girls– 0.5: Family income low– -0.5 and high– 0.5).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 4 presents unweighted means, standard deviations, ICCs, and cutoff scores for maternal depressive symptoms, household chaos, and children's behavioral and emotional problems at each time point. Bivariate correlations between all study variables are presented in Table 5. The rates of children's emotional and behavioral problems above the cutoff score varied respectively from 15.3%-22.5% and 24.3%-35.8% during lockdown to 14.1%-14.9% 18.8%-25.2% during routine periods. For maternal depression, during lockdowns 18.6%-30.4% of mothers reported symptoms above the cutoff score while during routine periods 15%-15.7% reported symptoms above the cutoff score.

In order to control possible confound, we ran one-way ANOVA to detect whether the seven main counties in Israel differed from each other in COVID-19 case rates in our sample and found no significant differences (F(6,223) = 1.076, p = 0.135, \({R}_{adjusted}^{2}\)= 0.04).

Changes in Children's Emotional and Behavioral Problems, Maternal Depressive Symptoms, and Household Chaos

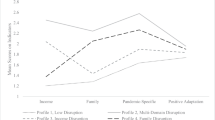

Significant time effects were found for both emotional (F(3,527.47) = 4.94, p = 0.002, \({R}_{pseudo}^{2}\)= 0.02) and behavioral (F(3,529.28) = 14.18, p < 0.0001, \({R}_{pseudo}^{2}\)= 0.07) problems, maternal depressive symptoms (F(3,498.94) = 30.30, p < 0.0001, \({R}_{pseudo}^{2}\)= 0.15), and household chaos (F(3,492.72) = 24.69, p < 0.0001, \({R}_{pseudo}^{2}\)= 0.12). Figure 1 presents the results of growth MLMs and planned contrasts with Tukey corrections.

Time Effects on Child Emotional and Behavioral Problems

As shown in panel A, for emotional problems, T1 contrasts with T2 and T4 were significant, such that problems were higher at T1, than in T2 (Est. = 0.48, SE = 0.13, t(518.51) = 3.68, p = 0.001, d = 0.29), and in T4 (Est. = 0.35, SE = 0.13, t(533.46) = 2.61, p = 0.044, d = 0.21). As shown in panel B, for behavioral problems T1’s contrasts with each time point were significant, such that problems were higher at T1, than in T2 (Est. = 0.84, SE = 0.14, t(519.55) = 5.94, p < 0.0001, d = 0.51), T3 (Est. = 0.55, SE = 0.13, t(530.47) = 4.01, p = 0.0003, d = 0.33), and T4 (Est. = 0.74, SE = 0.14, t(536.02) = 5.09, p < 0.0001, d = 0.44). All other contrasts were not significant. Altogether, these results suggest that both type of problems dropped significantly from the beginning of the second national lockdown (T1) to the second post-lockdown period (T2) and to the third post-lockdown period (T4). Furthermore, behavioral problems were higher at this lockdown (T1), than at the country’s third lockdown (T3).

The time X child sex interaction examined in two additional models was not significant for both emotional (F(3,500.14) = 0.44, p = 0.72, \({R}_{pseudo}^{2}\)= 0.00) and behavioral (F(3,501.37) = 0.41, p = 0.75, \({R}_{pseudo}^{2}\)= 0.01) problems, indicating that time effect was not different for boys and girls (see supplementary material).

Changes in Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Household Chaos

Overall, household chaos and maternal depressive symptoms showed the hypothesized pattern, in which levels were higher during lockdowns than during post-lockdown periods.

Specifically, as panel C shows, chaos levels dropped from T1 to T2 (from the beginning to the end of the second lockdown; T1-T2: Est. = 1.53, SE = 0.19, t(489.40) = 7.99, p < 0.0001, d = 0.52), rose at T3 (the beginning of the third lockdown) (T2-T3: Est. = -1.27, SE = 0.19, t(495.66) = -6.60, p < 0.0001, d = -0.43) and dropped again at T4 (the end of the third lockdown) (T3-T4: Est. = 0.51, SE = 0.19, t(488.72) = 2.68, p = 0.037, d = 0.17). Additionally, chaos dropped from T1 to T4 (T1-T4: Est. = 0.76, SE = 0.19, t(498.12) = 3.88, p < 0.0001, d = 0.26). Notably, chaos at T4 was significantly higher than at T2 (T2-T4: Est. = -0.76, SE = 0.20, t(496.40) = -3.78, p = 0.001, d = -0.26).

As panel D shows, maternal depressive symptoms showed a similar pattern – levels dropped from T1 to T2 (T1-T2: Est. = 3.26, SE = 0.37, t(491.25) = 8.73, p < 0.0001, d = 0.64), rose at T3 (T2-T3: Est. = -1.54, SE = 0.37, t(498.47) = -4.10, p = 0.0002, d = -0.30) and then dropped again at T4 (T3-T4: Est. = 1.10, SE = 0.37, t(489.69) = 2.97, p = 0.016, d = 0.22). In, general, maternal depressive symptoms levels were at their highest at the beginning of the second lockdown. That is, depressive symptoms were also higher at T1, when compared to T3 (Est. = 1.72, SE = 0.36, t(498.46) = 4.69, p < 0.0001, d = 0.34), and to T4 (Est. = 2.82, SE = 0.38, t(500.72) = 7.34, p < 0.0001, d = 0.56).

Between and Within Effects of Household Chaos and Maternal Depressive Symptoms on Children's Problems

Table 6 presents the estimated fixed effects of chaos and mothers' depressive symptoms on a children's emotional (left side) and behavioral problems (right side). Between-person effects were found for both maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos for both types of problems. That is, mothers experiencing higher depressive symptoms and household chaos reported having children with greater emotional and behavioral problems. A within-person effect was found for chaos predicting behavioral problems, such that fluctuations within household chaos positively predicted fluctuations in child behavioral problems. Higher chaos levels were associated with more behavioral problems within a specific family. However, these fluctuations were not associated with children's emotional problems. Furthermore, within-person effects of mothers’ depressive symptoms on children's behavioral and emotional problems were not significant. A significant negative lagged outcome (centered around the family's mean) was found to predict both emotional and behavioral outcomes: within each family more problems in the previous measurement were associated with fewer problems in the current measurement (and vice versa). Finally, children's age predicted behavioral problems, with older children exhibiting fewer behavioral problems than younger children.

Twenty-nine mothers did not report on the child's sex or family income, which are both level-2 variables. Hence, observations from these families were deleted when fitting the presented MLMs. We tested two additional models to check whether this affected the results, with the missing values substituted with zero (i.e., the mean of the binary coded variables). The pattern of results did not change. For full results, please see the supplementary material.

Discussion

In line with the systemic model of family functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic (Prime et al., 2020), the primary goal of the current study was to examine patterns of children's emotional and behavioral problems and familial factors (i.e., household chaos and maternal depressive symptoms) during and after lockdowns in the COVID-19 pandemic. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine these effects in a longitudinal, event-locked design. Overall, we found that emotional and behavioral problems, household chaos, and maternal depressive symptoms were the highest during the second lockdown and dropped in the post-lockdown periods. In addition, maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos positively predicted children's emotional and behavioral problems. Finally, fluctuations within household chaos positively predicted fluctuations in child behavioral but not emotional problems.

Changes in Emotional and Behavioral Problems, Household Chaos, and Maternal Depressive Symptoms

Several studies examined emotional and behavioral problems in children during the COVID-19 pandemic (Foley et al., 2021; Panda et al., 2021; Spinelli et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020; Yeasmin et al., 2020), but to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine these longitudinally and as they relate to specific stages in social distancing regulations (i.e., lockdowns) during the pandemic. Our first hypothesis was partially supported. Emotional and behavioral problems were high during the second lockdown, dropped significantly at its end, and remained low until the end of the third lockdown. Consistent with a recent study (Christner et al., 2021), older children also exhibited fewer behavioral problems than younger children. During environmental stress, like the COVID-19 period, more emotion regulation abilities are needed (Thompson, 1994). Since these abilities develop over time (Blandon et al., 2008), older children might have lower behavioral problems owing to their more advanced regulatory abilities. Finally, more behavior problems at a given time point predicted fewer problems in the consecutive time point. This can be explained by the general pattern of problems' change (as explored in hypothesis 1), as well as by regression toward the mean.

Maternal depressive symptoms and household chaos were high during lockdowns and dropped significantly at the end of each lockdown. Interestingly, maternal depressive symptoms, child behavioral problems, and household chaos declined from each lockdown to the next. These changes can be explained in several ways. The second lockdown (T1 in our study) started in September, after only two weeks of childcare returning from summer break. In addition, several major Jewish holidays (so-called high holidays) were celebrated atypically within the context of nuclear families (and not within the typically extended family context) due to COVID-19 regulations. The frequent changes in childcare systems and holiday-celebrating traditions might have contributed to the high levels of maternal depressive symptoms and children's emotional and behavioral problems. Drawn from Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory (1994), the impact of the macrosystem and the relations between the different elements in the environment may be more pronounced during holidays and during COVID-19 regulations than in everyday life. This may also explain why these symptoms declined from the second to the third lockdown, which did not coincide with a holiday season and were preceded by a longer period of stable childcare provision. Another possible explanation for this decline is that families grew accustomed to the lockdowns, establishing lockdown-specific routines, which contributed to stability. Thus, adjusting to the chronic stressor of lockdowns (Chen & Bonanno, 2020).

Beyond between lockdown changes, there was a steady increase in maternal and child symptomology during the lockdowns and a decrease at the end of each lockdown – only a week after returning to childcare. This highlights the importance of disruption to routines as a contributing factor to children's behavioral problems (Pilarz & Hill, 2014). Nevertheless, even after families reestablished their routines, behavioral problems and overall family distress remain relatively high, suggesting that the lockdowns have long-lasting detrimental effects on families (Stone et al., 2010). There are several reasons that maternal depressive symptoms may increase during lockdowns. First, many mothers are the main caregivers during routine times and the summer break, and were also the main caregivers during the second lockdown while working (Zoch et al., 2021) – which can result in occupational stress and lower work productivity (Collins et al., 2021; Feng & Savani, 2020; Petts et al., 2021). These stress factors can lead to parental burnout and exhaustion (Griffith, 2020). Depressive symptoms decreased at the end of each lockdown, returning to baseline. Thus, return to family daily routine lowered significantly depressive symptoms among mothers.

Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Child Emotional and Behavioral Problems

Maternal depressive symptoms positively predicted emotional problems and behavioral problems in children. This finding is not surprising and is consistent with theoretical perspectives and extant literature regarding maternal and child mental health (Goodman et al., 2011; Priel et al., 2020; Urizar & Muñoz, 2021). However, contrary to our hypothesis, we found no evidence that fluctuations in maternal depressive symptoms predicted changes in children's emotional and behavioral problems. It is possible that our sample was underpowered to detect these effects.

Household Chaos and Child Emotional and Behavioral Problems

Between-Subject Effects

Household chaos predicted both emotional problems and behavioral problems in children on average. This finding is in line with the literature showing associations between household chaos and adverse child outcomes (Coldwell et al., 2006; Dumas et al., 2005; Marsh et al., 2020) and specifically with behavior problems, even after controlling for parenting stress (Deater-Deckard et al., 2009; Evans & Wachs, 2010). During COVID-19 the family and house environments were the only environments that the child was exposed to for a prolonged period, which amplified familial effects. Even during the reported routine times, almost all extracurricular activities were canceled and social gatherings were forbidden, leaving the home environment more pronounced than ordinary times.

Within-Subject Effects

Our fourth hypothesis, suggesting that fluctuations in household chaos would predict changes in children's emotional and behavioral problems, was confirmed. Greater fluctuations in household chaos predicted greater changes in child behavioral problems. It seems that household chaos is a significant predictor of behavior problems, both as a between effect (higher levels of chaos predict greater behavior problems) and as a within effect (changes in chaos are associated with changes in behavioral problems). Indeed, the change in the family environment between lockdown and relative routine is tremendous, with resulting changes in sleep and wake times, screen time, etc. (Cellini et al., 2021; Eales et al., 2021; Romero et al., 2020) and families differ in how they made these transitions (Cassinat et al., 2021).

Limitations

Findings from this study should be considered in light of several limitations. First, due to our use of an online platform, we relied on mothers as single reporters for family, child, and maternal functioning which may lead to report bias and inflated associations between measures. A multi-method approach would increase the validity of the findings. An additional methodological limitation is the low internal validity in the SDQ at the T0 time point, in which participants reported about children's functioning two months prior to the pandemic outbreak. The use of retrospective reports may have reduced the validity of this measure. Second, we examined children over a wide range of ages with differing developmental abilities. While the current results capture broad effects, nuanced age-specific effects might not have been captured. In addition, our study focused on the pandemic timeline in a specific country, in which the lockdown period was especially restrictive, which raises the issue of generalization. Research on other countries, focusing on periods within the pandemic timeline in each country, is essential to understand the relevance of these findings beyond Israel. Another limitation is that this study started late in the pandemic, during the second lockdown. Levels of the main study variables may differ between the different lockdowns, and therefore this study does not reflect the whole course of the pandemic. Nevertheless, our longitudinal design enabled us to capture changes over time that are linked to specific events throughout the pandemic. Finally, although our sample was representative of the Israeli population in terms of family income, the majority of the participating mothers were highly educated. This may be a result of our use of an on-line sampling method that introduces selection bias. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized to the general population in Israel.

Conclusions and Implications

The present study contributes to understanding how COVID-19 lockdown regulations may affect maternal and child mental health. Our findings suggest that lockdowns had adverse effects on both mothers and children, as evident in greater maternal depressive symptoms, household chaos, child behavioral and emotional problems during these periods. These findings have implications for policy-maker decisions relevant for maternal and mental healthcare.

During lockdowns, instrumental and emotional support for primary caregivers is essential to decrease the detrimental effects on mothers and children, which persist beyond the lockdown. Screening for depressive symptoms among mothers of young children can also help target mothers in need of therapeutic interventions. Finally, maintaining household structure and routines are important targets for future interventions to assist parents in navigating the multiple challenges brought upon by the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Andersen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77–84.

Bariola, E., Gullone, E., & Hughes, E. K. (2011). Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(2), 198–212.

Björgvinsson, T., Kertz, S. J., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., McCoy, K. L., & Aderka, I. M. (2013). Psychometric properties of the CES-D-10 in a psychiatric sample. Assessment, 20(4), 429–436.

Blandon, A. Y., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & O’Brien, M. (2008). Individual differences in trajectories of emotion regulation processes: The effects of maternal depressive symptomatology and children’s physiological regulation. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1110–1123. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1110

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. International Encyclopedia of Education, 3(2), 37–43.

Cassinat, J. R., Whiteman, S. D., Serang, S., Dotterer, A. M., Mustillo, S. A., Maggs, J. L., & Kelly, B. C. (2021). Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1597–1610.

Cellini, N., Di Giorgio, E., Mioni, G., & Di Riso, D. (2021). Sleep and psychological difficulties in italian school-age children during COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 46(2), 153–167.

Chen, N., Deater-Deckard, K., & Bell, M. A. (2014). The role of temperament by family environment interactions in child maladjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1251–1262.

Chen, S., & Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S51–S54. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000685

Christner, N., Essler, S., Hazzam, A., & Paulus, M. (2021). Children’s psychological well-being and problem behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online study during the lockdown period in Germany. PLoS ONE, 16(6), e0253473.

Coldwell, J., Pike, A., & Dunn, J. (2006). Household chaos–links with parenting and child behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(11), 1116–1122.

Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., & Scarborough, W. J. (2021). COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 101–112.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

Crick, N. R., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2003). The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology, 15(3), 719–742. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940300035X

Cutrona, C. E., & Troutman, B. R. (1986). Social support, infant temperament, and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Development, 57(6), 1507–1518.

Davidson, B., Schmidt, E., Mallar, C., Mahmoud, F., Rothenberg, W., Hernandez, J., ... & Natale, R. (2021). Risk and resilience of well-being in caregivers of young children in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(2), 305–313.

Deater-Deckard, K., Mullineaux, P. Y., Beekman, C., Petrill, S. A., Schatschneider, C., & Thompson, L. A. (2009). Conduct problems, IQ, and household chaos: A longitudinal multi-informant study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(10), 1301–1308.

Dumas, J. E., Nissley, J., Nordstrom, A., Smith, E. P., Prinz, R. J., & Levine, D. W. (2005). Home chaos: Sociodemographic, parenting, interactional, and child correlates. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 93–104.

Eales, L., Gillespie, S., Alstat, R. A., Ferguson, G. M., & Carlson, S. M. (2021). Children’s screen and problematic media use in the united states before and during the covid-19 pandemic. Child Development, 92(5), e866–e882.

Evans, G. W., & Wachs, T. D. (2010). Chaos and its influence on children’s development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 6(2–3), 66–80.

Feng, Z., & Savani, K. (2020). Covid-19 created a gender gap in perceived work productivity and job satisfaction: Implications for dual-career parents working from home. Gender in Management, 35(7/8), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-07-2020-0202

Foley, S., Badinlou, F., Brocki, K. C., Frick, M. A., Ronchi, L., & Hughes, C. (2021). Family Function and Child Adjustment Difficulties in the COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11136.

Frigerio, A., Nettuno, F., & Nazzari, S. (2022). Maternal mood moderates the trajectory of emotional and behavioural problems from pre- to during the COVID-19 lockdown in preschool children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01925-0

Glynn, L. M., Davis, E. P., Luby, J. L., Baram, T. Z., & Sandman, C. A. (2021). A predictable home environment may protect child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurobiology of Stress, 14(1), 2352–2895.

Goodman, R. (1997). Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t00540-000

Goodman, R., Ford, T., Simmons, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 534–539.

Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458

Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27.

Grace, S. L., Evindar, A., & Stewart, D. E. (2003). The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: A review and critical analysis of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 6(4), 263–274.

Green, H., McGinnity, Á., Meltzer, H., Ford, T., & Goodman, R. (2005). In H. Green (Ed.), Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004 (p. 2005). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gregory, A. M., Eley, T. C., O’Connor, T. G., Rijsdijk, F. V., & Plomin, R. (2005). Family influences on the association between sleep problems and anxiety in a large sample of preschool aged twins. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(8), 1337–1348.

Griffith, A. K. (2020). Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 35(1), 1–7.

Gustafsson, B. M., Proczkowska-Björklund, M., & Gustafsson, P. A. (2017). Emotional and behavioural problems in Swedish preschool children rated by preschool teachers with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). BMC Pediatrics, 17(1), 1–10.

Hannigan, L. J., McAdams, T. A., & Eley, T. C. (2017). Developmental change in the association between adolescent depressive symptoms and the home environment: Results from a longitudinal, genetically informative investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(7), 787–797.

Hoffman, C., Crnic, K. A., & Baker, J. K. (2006). Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children's emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science and Practice, 6(4), 271–295.

Hoffman, L. (2014). Longitudinal analysis: Modeling within-person fluctuations and change. Taylor & Francis.

Jiao, W. Y., Wang, L. N., Liu, J., Fang, S. F., Jiao, F. Y., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., & Somekh, E. (2020). Behavioral and Emotional Disorders in Children during the COVID-19 Epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics, 221(1), 264-266.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013

Johnson, A. D., Martin, A., Partika, A., Phillips, D. A., Castle, S., & Tulsa SEED Study Team*. (2021). Chaos during the COVID-19 outbreak: Predictors of household chaos among low-income families during a pandemic. Family Relations, 71(1), 18–28.

Keiley, M. K., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2000). A cross-domain growth analysis: Externalizing and internalizing behaviors during 8 years of childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28(2), 161–179.

Kiel, E. J., & Kalomiris, A. E. (2015). Current themes in understanding children’s emotion regulation as developing from within the parent–child relationship. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 11–16.

Kiernan, K. E., & Huerta, M. C. (2008). Economic deprivation, maternal depression, parenting and children’s cognitive and emotional development in early childhood 1. The British Journal of Sociology, 59(4), 783–806.

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26.

Length, R. (2020). Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.4.7. https://CRAN.R-roject.org/package=emmeans. Accessed December 2021.

Li, Y., Wang, A., Wu, Y., Han, N., & Huang, H. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669119

Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561–592.

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M., Patil, I., Waggoner, P., & Makowski, D. (2021). performance: An R Package for Assessment, Comparison and Testing of Statistical Models. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60), 3139. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03139

Marchetti, D., Fontanesi, L., Di Giandomenico, S., Mazza, C., Roma, P., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). The effect of parent psychological distress on child hyperactivity/inattention during the COVID-19 lockdown: Testing the mediation of parent verbal hostility and child emotional symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 567062.

Marsh, S., Dobson, R., & Maddison, R. (2020). The relationship between household chaos and child, parent, and family outcomes: A systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–27.

Matheny, A. P., Jr., Wachs, T. D., Ludwig, J. L., & Phillips, K. (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16(3), 429–444.

Murray, L., Arteche, A., Fearon, P., Halligan, S., Goodyer, I., & Cooper, P. (2011). Maternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring up to 16 years of age. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(5), 460–470.

Nakagawa, S., Johnson, P. C. D., & Schielzeth, H. (2017). The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 14(134), 20170213. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0213

Panda, P. K., Gupta, J., Chowdhury, S. R., Kumar, R., Meena, A. K., Madaan, P., ... & Gulati, S. (2021). Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 67(1), fmaa122.

Patrick, S. W., Henkhaus, L. E., Zickafoose, J. S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Loch, S., ... & Davis, M. M. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics 146(4), e2020016824.

Petts, R. J., Carlson, D. L., & Pepin, J. R. (2021). A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 515–534.

Phelps, C., & Sperry, L. L. (2020). Children and the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S73–S75. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000861

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., ... & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892.

Pilarz, A. R., & Hill, H. D. (2014). Unstable and multiple child care arrangements and young children’s behavior. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 471–483.

Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67–73.

Priel, A., Zeev-Wolf, M., Djalovski, A., & Feldman, R. (2020). Maternal depression impairs child emotion understanding and executive functions: The role of dysregulated maternal care across the first decade of life. Emotion, 20(6), 1042–1058. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000614

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150.

Rohanachandra, Y. M., Prathapan, S., & Wijetunge, G. S. (2018). Characteristics of mothers’ depressive illness as predictors for emotional and behavioural problems in children in a Sri Lankan setting. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 33, 74–77.

Romero, E., López-Romero, L., Domínguez-Álvarez, B., Villar, P., & Gómez-Fraguela, J. A. (2020). Testing the effects of COVID-19 confinement in Spanish children: The role of parents’ distress, emotional problems and specific parenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 6975.

Russell, B. S., Hutchison, M., Tambling, R., Tomkunas, A. J., & Horton, A. L. (2020). Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(5), 671–682.

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., ... & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–11.

Sameroff, A. (2009). The transactional model. In A. Sameroff (Ed.), The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other (pp. 3–21). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11877-001

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81(1), 6–22.

Shockley, K. M., Clark, M. A., Dodd, H., & King, E. B. (2021). Work-family strategies during COVID-19: Examining gender dynamics among dual-earner couples with young children. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000857

Specht, I. O., Rohde, J. F., Nielsen, A. K., Larsen, S. C., & Heitmann, B. L. (2021). Changes in Emotional-Behavioral Functioning Among Pre-school Children Following the Initial Stage Danish COVID-19 Lockdown and Home Confinement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 643057.

Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Pastore, M., & Fasolo, M. (2020). Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1713.

Spinrad, T. L., Stifter, C. A., Donelan-McCall, N., & Turner, L. (2004). Mothers’ regulation strategies in response to toddlers’ affect: Links to later emotion self-regulation. Social Development, 13(1), 40–55.

Stone, L. L., Otten, R., Engels, R. C., Vermulst, A. A., & Janssens, J. M. (2010). Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4-to 12-year-olds: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(3), 254–274.

Team, R. C. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed December 2021.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 25–52.

Torales, J., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320.

Tso, W. W., Wong, R. S., Tung, K. T., Rao, N., Fu, K. W., Yam, J., ... & Wong, I. C. (2020). Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01680-8

Urizar, G. G., & Muñoz, R. F. (2021). Role of maternal depression on child development: A prospective analysis from pregnancy to early childhood. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1–13.

Wachs, T. D., & Evans, G. W. (2010). Chaos in context. In G. W. Evans & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Chaos and its influence on children's development: An ecological perspective (pp. 3–13). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12057-001

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet, 395(10228), 945–947.

Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province. China. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 898–900.

Yamada, M., Tanaka, K., Arakawa, M., & Miyake, Y. (2021). Perinatal maternal depressive symptoms and risk of behavioral problems at five years. Pediatric Research, 1–7.

Yeasmin, S., Banik, R., Hossain, S., Hossain, M. N., Mahumud, R., Salma, N., & Hossain, M. M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 105277.

Zhang, X. (2022). Household chaos and caregivers' and young children's mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mediation model. Journal of child and family studies, 1–11.

Zoch, G., Bächmann, A. C., & Vicari, B. (2021). Who cares when care closes? Care-arrangements and parental working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. European Societies, 23(sup1), S576–S588.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the psychology department ethics committee at Ben Gurion University of the Negev.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gordon-Hacker, A., Bar-Shachar, Y., Egotubov, A. et al. Trajectories and Associations Between Maternal Depressive Symptoms, Household Chaos and Children's Adjustment through the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Four-Wave Longitudinal Study. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 51, 103–117 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-022-00954-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-022-00954-w