Abstract

We analyze the unilateral introduction of a destination-based corporate cash-flow tax system (DBT), as proposed by Auerbach and Devereux (AEJ Policy 2018). We show that, first, the DBT rate is decision-neutral only if the source tax country makes the DBT payments deductible from its tax base. Second, a unilateral DBT introduction is, in many aspects, equivalent to completely abolishing the corporate tax and, instead, taxing domestic investors based upon their worldwide profit income, net of foreign taxes and on accrual. In this sense, the DBT is actually a pure residence-based tax. This implies that, from a foreign investor’s perspective, the DBT country is like a zero-rate tax haven and has the same gravitational power on taxable profits and economic activity. Third, the location of profit and activity within its borders is, however, without any fiscal value for the DBT country. Fourth, the introduction of a DBT system reduces national income. Fifth, the DBT country can only individually benefit from its new tax system if public goods provision is substantially increased. Finally, it is optimal to complement a unilateral DBT system with a source-based tax.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the following, we will not discuss any aspect of cash-flow taxation, rather simply assume this feature of the tax system as given.

The Mirrlees Report discusses the idea, too, see Auerbach et al. (2010).

See, e.g., Becker and Englisch (2017). Hebous and Klemm (2018) also discuss specific alternatives like implementation via border taxes or nondeductibility of certain expenses. The authors’ main focus is on replacing the cash-flow part of the destination-based cash-flow tax by alternative techniques to implement investment neutrality: allowance for corporate equity (ACE) and allowance for corporate capital.

A similar approach is taken by Bond and Gresik (2019) who analyze a unilateral introduction of destination-based cash-flow taxation in a north–south type of trade model with heterogeneous firms and endogenous entry. Their analysis is complementary to ours, as it focuses on the implications of transfer pricing on market allocation and markups under imperfect competition. Hebous et al. (2019) measure the implications of the USA introducing unilaterally a system of destination-based cash-flow taxes. They find that revenue losses are concentrated among the countries with the closest trade links to the USA like Canada and Mexico.

Feldstein and Hartman (1979) characterize such a system as “neutral” from a national point of view.

Auerbach et al. (2017a, b) emphasize that, with global introduction of DBT, the usual techniques of gaming the system do not work anymore (a claim that is qualified, at least for the specific Ryan blueprint proposal discussed in the USA, by Avi-Yonah and Clausing (2017) and Miller (2017). With unilateral (or better: less than global) introduction, however, there may be even stronger incentives to distort the profit and real resource allocation than in the current system.

This assumption does not imply zero profits, though. The firm is endowed with three kinds of fixed factors: one at the locations of intermediate production, one at the locations of consumption good production and the management capacity M.

If the firm is understood as a representative one, the real response to taxation may be interpreted as a combination of reallocation of productive inputs to existing plants (the intensive margin) and the location of new plants in the low-tax country (the extensive margin).

This is obvious for country F. For country H, net revenue from taxing the competitive sector equals \(-\tau \left( c_{2}+k+g-1\right) +\tau \left( 1-c_{2}^{*}-k^{*}-g^{*}\right) \), which—due to (1)—is zero.

To see this, consider a firm that purchases one unit of capital in country F and sells it to the MNE affiliate in H. With the market price in H given by 1 (recall that w is normalized to unity), its profit is \(\left( 1-t^{*}\right) \left( \left( 1-\tau \right) -w^{*}\right) \). Selling the unit in F yields a profit of \(\left( 1-t^{*}\right) \left( p_{2}^{*}-w^{*}\right) \). Both profits are zero when \(p_{2}^{*}=w^{*}=1-\tau \).

AD18 use a slightly richer notation with gross exports \(e^{*}\) and e to the home country and from the home country, respectively, and with two distinct transfer prices, \(q^{*}\) and q. If transfer prices need to be equal (an assumption shared by AD18), there is no loss of information if nominal net exports are denoted \(q^{*}e^{*}\) as above.

Thus, the burden of the DBT depends on where the firm profits are consumed. Changing the location of consumption would therefore imply avoiding the tax. In the model framework used here, households are assumed to be immobile, though. Note that this also implies that changing the headquarters location of the firm does not have any tax implications (neither for the DBT nor the source tax).

For benchmark purposes, consider the case in which both countries apply a pure source tax system (i.e., \(\tau =0\)). Since public goods g and \(g^{*}\) are entirely financed out of tax payments made by the MNE, the budget constraints are given by \(p_{1}c_{1}+c_{2}=1+\beta \left( \Pi -g^{*}-g\right) \) and \(p_{1}^{*}c_{1}+c_{2}^{*}=1+\left( 1-\beta \right) \left( \Pi -g^{*}-g\right) \). Utility levels can be expressed as

An increase in g by one unit has a (direct) cost of \(\beta <1\) from the viewpoint of country H (in addition to the efficiency cost due to the behavioral response by the firm). For later purpose, note that national incomes are given by \(1+\beta \left( \Pi -g^{*}\right) +\left( 1-\beta \right) g\) in country H and by \(1+\left( 1-\beta \right) \left( \Pi -g\right) +\beta g^{*}\) in country F.

The foreign household’s budget constraint reads \(p_{1}^{*}c_{1}^{*}+p_{2}^{*}c_{2}^{*}=w^{*}+\left( 1-\beta \right) \left( 1-\tau \right) \left( \Pi -g^{*}\right) \). Dividing by \(p_{2}^{*}=1-\tau \) gives the expression in (17).

This can be shown as follows. Its tax base is given by \(p_{1}c_{1}-k\) in sector 1 and \(1-c_{2}^{*}-k^{*}-g^{*}\) in sector 2 (assuming here that there are net exports in sector 2 from F to H). Using the budget constraint of country F’s household and replacing \(1-c_{2}^{*}\) by \({\tilde{p}}_{1}^{*}c_{1}^{*}-\left( 1-\beta \right) \left( \Pi -g^{*}\right) \), the tax base can be expressed as

$$\begin{aligned} p_{1}c_{1}-k+{\tilde{p}}_{1}^{*}c_{1}^{*}-k^{*}-\Pi +\beta \left( \Pi -g^{*}\right) \end{aligned}$$which boils down to \(\beta \left( \Pi -g^{*}\right) \).

A tax rate of 60% is not the optimal tax rate from the viewpoint of country F. It is actually higher than 60%. This implies that, with optimal tax rate setting by country F, country H is even worse off (due to larger distortion of the international production allocation and lower MNE profits) and country H is better off.

This finding seems to be of special relevance to the policy debate in the USA. As we show above, introducing a DBT unilaterally is only attractive because it allows increasing the level of public goods. The strong tax cut associated with the original plan for a border tax adjustment (GOP 2016) seems to be at odds with this finding. Moreover, since foreign firm ownership reduces the (perceived) cost of public goods provision (which makes it more efficient) and allows for tax exporting, strong involvement of foreigners reduces the likelihood that a country would individually benefit from unilaterally introducing DBT. Ironically, the Trump administration seemed to suggest that it is exactly because foreigners would bear a large part of the tax burden, that a border tax (i.e., a DBT system) would pay off for the USA.

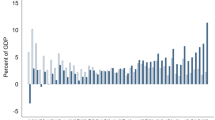

The tax rate difference under a symmetric source-based tax system is close to 20% points, whereas under a German DBT system the difference would be 12.5% points (the Irish statutory rate minus the zero rate on foreign profits under German DBT).

Moreover, as emphasized by AD18 and others, a DBT destroys the business model for tax havens—and, thus, is likely to reduce the supply of tax sheltering services.

References

Auerbach, A. J., & Devereux, M. P. (2018). Cash-Flow Taxes in an International Setting. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10(3), 69–94.

Auerbach, A. J., Devereux, M. P., Keen, M., & Vella, J. (2017a). Destination-based cash flow taxation. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation WP 17/01.

Auerbach, A. J., Devereux, M. P., Keen, M., & Vella, J. (2017b). International tax planning under the destination-based cash flow tax. National Tax Journal, 70(4), 783–802.

Auerbach, A. J., Devereux, M. P., & Simpson, H. (2010). Taxing corporate income. In J. Mirrlees, et al. (Eds.), Dimensions of tax design: The Mirrlees Review (pp. 837–893). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Avi-Yonah, R. S. (2000). Globalization, tax competition, and the fiscal crisis of the welfare state. Harvard Law Review, 113, 1573–1676.

Avi-Yonah, R. S., & Clausing, K. (2017). Problems with destination-based corporate taxes and the Ryan blueprint, Working paper.

Barbiero, O., Farhi, E., Gopinath, G., & Itskhoki, O. (2018). The macroeconomics of border taxes. In: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2018, Vol. 33. Eichenbaum and Parker.

Becker, J., & Englisch, J. (2017). A European perspective on the US plans for a destination based cash flow tax. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation Working Paper WP 17/03.

Bond, E., & Gresik, T. (2019). Unilateral tax reform: Border adjusted taxes, cash flow taxes, and transfer pricing, Working Paper.

Bond, S. R., & Devereux, M. P. (2002). Cash flow taxes in an open economy. CEPR Discussion Paper 3401.

Buiter, W. (2017). Exchange rate implications of border tax adjustment neutrality, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP 11885.

Cui, W. (2017). Destination-based cash-flow taxation: a critical appraisal. University of Toronto Law Journal, 67(2), 301–347.

Devereux, M. P., & de la Feria, R. (2014). Designing and implementing a destination-based corporate tax. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation WP 14/07.

Feldstein, M. S., & Hartman, D. (1979). The optimal taxation of foreign source investment income. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 93(4), 613–629.

Freund, C., & Gagnon, J. E. (2017). Effects of consumption taxes on real exchange rates and trade balances. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 17-5.

GOP. (2016). A better way—Our vision for a confident America, 24 June 2016.

Graetz, M. J. (2017). The known unknowns of the business tax reforms proposed in the house republican blueprint. Columbia Journal of Tax Law, 8, 117–169.

Grinberg, I. (2017). A destination-based cash flow tax can be structured to comply with world trade organization rules. National Tax Journal, 70, 803–818.

Hebous, A., & Klemm, A. (2018). A Destination-based allowance for corporate equity, CESifo Working Paper No. 7363.

Hebous, S., Klemm, A., & Stausholm, S. (2019). Revenue implications of destination-based cash-flow taxation, CESifo Working Paper No. 7457.

Lamensch, M. (2017). Destination based taxation of corporate profits—Preliminary findings regarding tax collection in cross-border situations. Oxford Centre for Business Taxation Working paper series (WP17/16).

Miller, D. S. (2017). Tax planning under the destination based cash flow tax: A guide for policy makers and practitioners. Columbia Journal of Tax Law, 8, 295–306.

Musgrave, P. B. (1969). United States taxation of foreign investment income: Issues and arguments. Cambridge, MA, International Tax Program, Harvard Law School.

Richman, P. B. (1963). Taxation of foreign investment income—An economic analysis. Baltimore.

Schön, W. (2016). Destination-based income taxation and WTO law: A note. Max planck institute for tax law and public finance working paper 2016—03.

Acknowledgements

We thank referees as well as participants of the 2017 Summer Symposium of the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation and the CESifo Venice Summer Institute 2018 for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Derivation of equations (9) to (12)

The first-order conditions are—with \(e^{*}=x_{1}-f\left( k,m\right) \)

With \(q^{*}=\left( 1-\lambda \right) \frac{1}{f_{1}}\), these conditions may be expressed as

from which follow equations (9) to (12) in the main text.

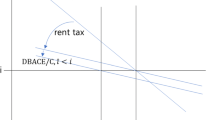

1.2 Setting \(\delta <1\)

Allowing for less-than-full deductibility in F of DBT payments made in H has substantial consequences for the effects of a unilateral DBT introduction. With \(\delta <1\), the equilibrium price of good 2 in F is \( p_{2}^{*}=1-\tau \left( \frac{1-\delta t^{*}}{1-t^{*}}\right) \). Then, the first-order conditions are

With \(p_{1}^{*}h^{*\prime }=\frac{p_{2}^{*}}{f_{1}^{*}}\) and \(q^{*}=\frac{1-\lambda }{f_{1}}\), these conditions can be expressed as

Assume that \(t<t^{*}\), i.e., there is an incentive to shift resources and profits to the DBT country. In the absence of profit shifting (\(\lambda =0\) ), \(\delta <1\) implies that the distortion of management allocation is worse (i.e., the right-hand side of the second condition is smaller). An increase in \(\tau \) would exacerbate this distortion.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, J., Englisch, J. Unilateral introduction of destination-based cash-flow taxation. Int Tax Public Finance 27, 495–513 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09579-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09579-0