Abstract

Taxing aid was often discussed, but never implemented. This issue has now returned to the fore. First, many developing countries reform their tax system becoming more “reasonable” and eliminating one of the main justifications for aid-related tax exemptions. Second, the International Conference on Financing for Development held in Addis Ababa in August 2015 emphasised domestic revenue mobilisation as the main source of development finance. However, the broadening of tax base faces the proliferation of special tax arrangements, fuelled in part by the tax-exempt status of Official Development Assistance. Exemptions for project aid could represent as much as 3 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in countries where tax revenues barely surpass 15 per cent of GDP. In addition to loss of tax revenue, tax exemptions for project aid have particularly damaging effects on the formalisation of the economies of recipient countries. Moreover, systematic exemption reduces the credibility of the policies of donor countries and the consistency of their aid policy. Last, the taxation of aid meets the commitment made by donors in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (2005) to use recipient countries’ national Public Finance Management systems. This note reviews tax exemptions of foreign aid-funded projects: their consequences in terms of domestic revenue mobilisation in recipient countries, the induced inconsistency of foreign aid policy, their main historical justifications, and recent moves from some donor countries towards the taxation of their aid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This tax revenue does not include external tax revenue in the form of tariff receipts or any levies raised on countries’ foreign trade, which have declined.

In 2014, ODA represented only 23% of finance provided by developed countries (OECD data).

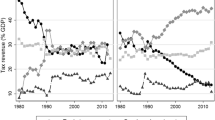

Authors’ calculation based on UNU-Wider database (https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/government-revenue-dataset).

For example, Mansour and Rota-Graziosi (2014) show that WAEMU member states compete mainly via special tax arrangements offered to firms as most member states’ taxes and duties are regulated by widely followed community directives.

Notable sources of tax expenditure are sectoral codes (mining, oil), investment codes, ministerial decrees, and even establishment agreements and ad hoc decisions.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of aid: project aid, which consists in financing certain public goods or services, in particular infrastructure (roads, bridges, ports), and budget support, which consists of transfers to the government of a developing country. Project aid represents around 70% of all ODA (see Fig. 1).

A recent exception is Steel et al. (2018), who discuss the rationale for ODA tax exemptions through a survey covering 47 countries.

Such a crowding out effect of aid is not new in the literature. Focusing on the US Public Law 480, which established the American food aid program in 1954, Schultz (1960) stressed the risk of a disincentive effect of this aid on domestic agricultural producers in recipient countries.

Nevertheless, this work has recently been the subject of debate, and new studies have showed that the negative relationship put forward is not so robust. In particular, Clist and Morrissey (2011) and Carter (2013) showed that this relationship is not robust relative to sample or specification changes and that it results from an endogeneity bias. Responding to the work of Benedek et al. (2012), Clist (2014) also concluded that these studies were not robust and attributed the negative effect of aid to poor econometric specifications and failure to take into account the obvious presence of endogeneity bias.

These exemptions even create the need for further aid, leading to the Samaritan dilemma described by Buchanan (1975).

For example, with the complicity of a customs officer, a merchant could claim a tax exemption granted to a donor and import goods free of any tax or duty without the donor knowing.

The reciprocity principle may allow an extension of some tax advantages. However, this principle does not seem relevant when it is applied between developed and developing countries. Moreover, numerous scandals of tax abuse prejudice current practices.

Authors’ calculation based on World Bank data.

We compile the datasets on tax revenues provided from the UNU-Wider (https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/government-revenue-dataset) and on aid from the OECD (https://data.oecd.org/oda/net-oda.htm). We multiply the total tax and indirect taxes revenue-to-GDP ratios by the aid-to-GDP ratio. We deduce then an estimate of total tax and indirect taxes revenue losses resulting from the tax exemption of aid.

For Liberia, this figure rises even to 7.43 per cent but we should be cautious with the accuracy of used data since the UNU-Wider tax revenue-to-GDP ratio is equal to 31.04 per cent; this same ratio is equal to 12.9 per cent in 2013 in the Government Finance Statistics of the International Monetary Fund.

Steel et al (2018) stressed that VAT and duties exemptions are far more frequent than other tax exemptions.

As in many developing countries, it is impossible to estimate the cost of customs exemptions granted in Madagascar to project aid from customs data: (1) the codes used for exemptions in the computer system do not separate them; and (2) they are sometimes considered fully taxed imports if taxes and duties are collected as “balancing transactions”.

Authors’ calculation.

For example, apart from frequent and practically uncontrollable misappropriations, exemptions create opportunities for customs evasion through the fraudulent use of the tax identification number of the development partner without its knowledge.

For example, a local supplier will not be able to collect VAT and therefore to deduce VAT from its inputs. Instead, it will be forced to carry over some of this VAT in the price of its service or reduce its profit margin. Exemptions for the suppliers of the donor’s supplier could also be considered. This solution, which has been adopted in the agricultural, mining, and oil sectors, is particularly costly in terms of tax revenue and does not favour the formalisation of the economy.

See the Instruction No. 196/414/PM/MBRSP portant mesures d’application du régime fiscal des marches publics et projets publics du 13/12/1996.

Knack (2013) studied decisions to bypass recipient country institutions. The author highlighted the role of donors’ trust in these institutions, their quality, and risk aversion on the part of donor countries.

These rates could vary very significantly depending on whether or not the good could be produced locally.

These authors test empirically the effect of aid on democracy in 108 recipient countries over the period 1960 to 1999.

“To eliminate these inconsistencies and distortions and reduce transaction costs in the administration of Bank-financed projects, Bank policy would be changed to provide Bank financing for the reasonable costs of taxes and duties associated with project expenditures.” (World Bank 2004, p. 11). The authors are not aware of any effective implementation of such a commitment.

The ITD is a joint initiative of the European Union Commission, the Inter-American Development Bank, the IMF, the OECD, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Center of Tax Administrations.

UN (2018) provides only some comments to the 2007 draft guidelines.

In 2010, France considered establishing a working task force to study this issue. This working group would have measured the impact of aid taxation and discussed the issue with the various stakeholders before presenting a proposal to the DAC to set in motion a fresh round of discussion.

There are a few exceptions: Romania is opposed but uses national procedures for 90% of its aid; Belgium and Luxembourg are in favour but have done little to meet the commitments of the Paris Declaration. The use of national systems is a signal of confidence among donors in the systems of recipient countries, which may explain donors’ stance on the taxation of project aid.

Some countries are beginning to forgo exemptions. France has embarked on this process through “debt reduction and development contracts” (C2D), which finance tax-inclusive development projects and programs.

References

Benedek, D., Crivelli, E., Gupta, S., & Muthoora, P. (2012). Foreign aid and revenue: Still a crowding out effect?, IMF Working Papers WP/12/186, International Monetary Fund.

Bräutigam, D., Feldstadt, O.-H., & Moore, M. (2008). Taxation and State-building in developing countries: Capacity and consent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, J. M. (1975). The Samaritan’s dilemma. In E. S. Phelps (Ed.), Altruism, morality and economic theory (pp. 71–85). New York: Russel Sage foundation.

Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (2000). Aid, Policies, and Growth. American Economic Review,90(4), 847–868.

Carter, P. (2013). Does foreign aid displace domestic taxation? Journal of Globalization and Development,4(1), 1–47.

Clemens, M. A., Radelet, S., Bhavnani, R., & Bazzi, S. (2012). Counting chickens when they hatch: timing and the effects of aid on growth. Economic Journal,122, 590–617.

Clist, P. (2014). Foreign aid and domestic taxation: Multiple sources, one conclusion. ICTD, Working Paper 20. Brighton: International Centre for Tax and Development.

Clist, P., & Morrissey, O. (2011). Aid and tax revenue: Signs of a positive effect since the 1980s. Journal of International Development,23(2), 165–180.

Deaton, B. J. (1980). Public Law 480: The critical choices. American Journal of Agricultural Economics,62(5), 988–992.

Déclaration de Paris sur l’efficacité de l’aide au développement (2005). Paris.

Djankov, S., Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2008). The curse of aid. Journal of Economic Growth,13(3), 169–194.

Gupta, S., Clements, B., Pivovarsky, A., & Tiongson, E. (2004). Foreign aid and revenue response: does the composition of aid matter? In S. Gupta, B. Clements, & G. Inchauste (Eds.), Helping countries develop: the role of fiscal policy. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2011). Revenue mobilization in developing countries, Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund.

Keen, M., & Mansour, M. (2010). Revenue mobilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges from globalisation. Development Policy Review, 28(5).

Knack, S. (2013). Aid and donor trust in recipient country systems. Journal of Development Economics,101, 316–329.

Mansour, M., & Rota-Graziosi, G. (2014). Tax coordination and competition in the West African Economic and Monetary Union. Tax Note International, Special Reports.

Op de Beke, A. (2014). Réforme des administrations fiscales dans les pays francophones en Afrique subsaharienne, International Monetary Fund.

Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques (OCDE) (2009). Issues note on the tax treatment of aid funded goods and services, Task team on taxation and governance, The Serena Hotel, Kampala, 18 November 2009.

Orlowski, D. (2007). Donors’ principles and resulting stress: Indirect taxes and donor-funded public works. Fiscal policy and tax incidence, Ministry of Planning and Development of Mozambique.

Schultz, T. W. (1960). Value of U.S. farm surpluses to underdeveloped countries. Journal of Farm Economics,42(5), 1019–1030.

Steel, I., Dom, R., Long, C., Monkam, N., & Carter, P. (2018). The taxation of foreign aid. Don’t ask, don’t tell, don’t know, ODI, Brief Paper.

UN. (2007). Tax treatment of donor-financed projects: Draft guidelines prepared by the staff of the international tax dialogue steering group. Geneva: United Nations Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters.

UN. (2018). Revision of the draft guidelines on the tax treatment of ODA. New York: United Nations Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters.

World Bank. (2004). Eligbility of expenditures in Wold Bank lending: A new policy framework. Operations Policy and Country Services, March, 56 p.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support received from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche of the French government through the program “Investissements d’avenir” (ANR-10-LABX-14-01); the usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caldeira, É., Geourjon, AM. & Rota-Graziosi, G. Taxing aid: the end of a paradox?. Int Tax Public Finance 27, 240–255 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09573-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-019-09573-6

Keywords

- Tax

- Exemption

- Tax expenditure

- Official Development Assistance

- Domestic revenue mobilisation

- Developing countries