Abstract

Adaptation has become a priority in global climate change governance since the adoption of the Cancun Adaptation Framework and the Paris Agreement. Adaptation to climate change has been increasingly recognized as a multi-level governance challenge in both the United Nations Framework Climate Change Convention (UNFCCC) regime and academic literature. This recognition often includes, explicitly or implicitly, the role that learning can play across governance levels to accelerate and scale up responses to address adaptation challenges. However, there is no comprehensive assessment in academic literature of how multi-level learning has been considered in the UNFCCC regime, what the enabling factors are, and the outcomes of such learning. Drawing on approaches suggested by multi-level governance and learning literature, this paper seeks to fill this knowledge gap by focusing on the ways in which the UNFCCC multilateral process enables multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation and how it could be enhanced. This will be accomplished through a legal–technical analysis of the enabling factors of multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation under the UNFCCC. Qualitative research methods have been applied for the thematic analysis of selected documentation, complemented by interviews and personal observations of adaptation negotiations in the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. Results are presented according to three research questions oriented to understand how institutional design of adaptation under the UNFCCC enables multi-level learning; the learning strategies adopted across levels of governance; and the way the UNFCCC regime understands the contribution of multi-level learning for adaptation outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has repeatedly stressed the need to accelerate the depth and breadth of the global response to climate change across scales and levels of governance (e.g. de Coninck et al., 2018; Pörtner et al., 2022). The adaptation response requires not only the scaling up of technological measures, but also the development, testing, and transference of adequate policy measures across countries and the creation of economic and social conditions to enable change and transformation (Pauw & Klein, 2020).

Despite an initial emphasis on mitigation, adaptation has become central in the United Nations Framework Climate Change Convention (UNFCCC) process, and it has received an increasingly prominent position in the evolution of the international climate regime. The Cancun Adaptation Framework (CAF), adopted under the UNFCCC in 2010, and the Paris Agreement (PA), adopted in 2015, established the institutional framework for enhanced ambition on adaptation worldwide. The PA took another significant step forward in making adaptation an equal priority with mitigation, calling for stronger adaptation commitments from states and assessing progress periodically as part of the PA transparency framework, in addition to calling for more ambitious funding and technical assistance provided by the international community (Lesnikowski et al., 2017).

The multilateral adaptation regime that is emerging is built up of multiple parallel initiatives involving a range of actors at different governance levels determining climate change policy and actions (e.g. Böhmelt et al., 2014; Okereke et al., 2009); nevertheless, it remains strongly influenced by the UNFCCC mandate and process. Adaptation to climate change is a relatively recent policy domain across all countries, and there is much to learn within and across countries on how to design and put in place effective policies and how to design governance. We therefore agree with scholars who consider learning to be an important component in the governance of climate change adaptation (henceforth the governance of adaptation). Learning is recognized for its role in contributing to enhanced understanding of the challenges posed by climate change and anticipating and adjusting the course of action (e.g. Pelling et al., 2008; Tschakert & Dietrich, 2010); accelerating and scaling up possible responses (Fünfgeld, 2015); for incorporating different views and perspectives, in particular from vulnerable groups (e.g. Jabeen et al., 2010; Naess, 2013); and as a key functionality of governance settings to enhance resilience and adaptive capacity (e.g. Pahl-Wostl, 2009; Siebenhüner, 2008).

The scholarly literature has also recognized the role of learning in the UNFCCC context, for example, to disseminate the results of science (Minx et al., 2017), as well as the need to reflect and learn about progress and how to overcome stagnation in the evolution of the global climate regime (Depledge, 2006; Gupta, 2016; Rietig, 2019). Furthermore, as described below, the UNFCCC process itself recognizes the importance of learning to promote adaptation.

Governance arrangements and institutions can enable learning (e.g. Collins & Ison, 2009; Hackmann, 2016; Siebenhüner, 2008), and there is a small but growing literature exploring the role of learning in process and institutional design for adaptation (e.g. Huntjens et al., 2012; Pahl-Wostl, 2009; Sandström et al., 2020).

While the contribution of multi-level learning to institutional and policy design for adaptation is underscored in the scholarly literature and an important set of adaptation rules is defined by the UNFCCC, there is no comprehensive assessment yet of how multi-level learning has been enabled by the UNFCCC regime, and how it can contribute to fulfilling its mandate and goals.

This paper seeks to address this knowledge gap by focusing on the ways in which the UNFCCC multilateral process enables multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation and how it could be enhanced. Our empirical assessment consists of, on the one hand, a comprehensive legal–technical analysis to identify enabling factors for multi-level learning based on a review of UNFCCC documents related to adaptation since the inception of the UNFCCC process. On the other hand, we analyse the factors for enhanced multi-level learning within the governance system, and the adopted learning strategies. The research applies an analytical framework for the assessment of multi-level learning in the UNFCCC context, based on a review of academic literature and validated through the thematic analysis of UNFCCC documentation.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the analytical framework to assess multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation and the research questions guiding this paper. In Sect. 3, the methods used are described. The data and results are analysed in Sect. 4, and in Sects. 5 and 6 we discuss this study’s findings and contribution to multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation research and draw conclusions.

2 Analytical framework

The notion of multi-level learning is linked to the conceptualization of multi-level governance (Hooghe & Marks, 2010), which illustrates the interplay and overlaps of different jurisdiction levels in the governance of a particular territory. In this context, the governance of adaptation has been increasingly recognized as a multi-level governance challenge (di Gregorio et al., 2019). Environmental and multi-level governance scholars have frequently argued that adaptation requires a variety of stakeholders to take actions and decisions across different governance levels (e.g. Armitage, 2008; Dewulf et al., 2015) and that institutional arrangements across levels, including the global and international levels, are key to delineating effective adaptation (Armitage, 2008; Vinke-de Kruijf & Pahl-Wostl, 2016).

Multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation implies that learning takes place not only within, but also across, different governance levels. We understand this type of learning as the interplay of policy learning (Hall, 1993; Sabatier, 1988) and social learning (e.g. Reed et al. 2010) processes happening across different governance levels on policy-relevant aspects of adaptation (Gonzales-Iwanciw et al., 2020).

The conceptualization of multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation as the interplay of social and policy learning leads to a focus on the interaction of different actors learning collectively and influencing the objectives and outcomes of the policy process. As stated by Sabatier (1988), different portions of the society or advocacy coalitions influence the policy agenda and their outcomes through their respective interests, capabilities, and belief systems.

The governance of adaptation literature when seeking to assess learning has focused on the factors likely to encourage or hamper learning processes and the outcomes of such learning (e.g. Armitage et al., 2018; Gerlak & Heikkila, 2011; Sabatier, 1988). Learning is tightly linked to the notion of change—incremental or transformational—to enhance performance or the ability to produce desired outcomes (Appelbaum & Goransson, 1997; Henderson, 2002). Those changes are reflected as adjustments in the structure and functioning of the governance regime itself (e.g. Armitage et al., 2018; Pahl-Wostl, 2009).

Social learning outcomes are outlined by through the following defining characteristics: change in understanding has taken place in the individuals involved; this change goes beyond the individual and involves wider social units including communities of practice; and change occurs through social interactions and processes among actors in a social network. The policy learning literature, on the other hand, discusses learning outcomes mainly in terms of policy change and the performance of policy measures in addressing desired outcomes (Conzelmann, 1998; Sanderson, 2002). Policy learning is fostered by providing the incentives for enhanced policy performance, institutional design and functioning (Dovers & Hezri, 2010; Sanderson, 2002), including enhanced capabilities for innovation (e.g. Capello & Faggian, 2005; Tschakert & Dietrich, 2010).

Most of the factors likely to influence learning processes and outcomes fit within a social network’s structure, its dynamics, functional domain, and exogenous factors or disturbances (Gerlak & Heikkila, 2011). Factors related to the structure are linked to the level of integration or fragmentation of the actors in an organization, the level of differentiation of actors’ roles that encourage or hamper collaboration, information sharing, and the dissemination of learning and ideas (Vink et al., 2013). Factors linked to the dynamics of the social network result from the frequency and intensity of actors’ interactions, the facilitative role of leadership, and the social demands and needs that shape a learning culture (Armitage et al., 2018; Gerlak & Heikkila, 2019).Factors that fit in the functional domain—for example, as information and communication technologies become available—change how critical information and knowledge is stored, processed, and shared, supporting and reshaping the learning culture. In addition, both the social and the policy learning literature recognize the role of exogenous perturbations, such as economic crises or climate-related impacts, altering social structures and dynamics, in ways that could promote learning.

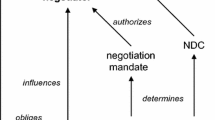

Based on this discussion, Fig. 1 outlines the analytical framework applied for the empirical examination of adaptation-related multi-level learning in the UNFCCC context. Mandate and institutional arrangements resulting from key decisions in the UNFCCC context build the fundamental structure that enables multi-level learning. Working modalities is another category of enabling factor for multi-level learning. These are well established in UNFCCC decisions, like institutionalized gatherings for sharing experiences and reporting, and largely define the dynamics of interactions between the actors.

Multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation. The visualization describes an analytical framework for the process of multi-level learning: A the enabling factors that influence the process including the mandate and institutional arrangements across governance levels and adopted working modalities; and learning challenges and needs of different groups B The learning strategies are assessed through changes in their cognitive, normative, and relational dimensions C The learning outcomes of the process are coded and analysed through the review process

The structure of institutional arrangements can be described as a network of multi-level learning nodes defined as institutionalized or informal arrangements of social and policy learning practices and routines occurring across governance levels (Gonzales-Iwanciw et al., 2021). Multi-level learning takes place within, but also across, those nodes through network interactions, for example, a task force that combines agents’ knowledge and experience obtained at different governance levels through different institutionalized procedures. These nodes operate based on formal decisions from the UNFCCC or simply assume roles and functions informally depending on the demand of knowledge interactions and the dynamic of the social network.

We also consider as factors the learning needs and challenges of the general process of adaptation under the UNFCCC, and the learning needs of different negotiation groups resulting from the formal and informal interactions, for example—the information and knowledge needs to support adaptation in Small Island Development States (SIDS).

The learning strategies commonly used in the UNFCCC context across governance levels are assessed through potential changes in the cognitive, normative, and relational dimensions of multi-level learning (Baird et al., 2014; Huitema et al., 2010). Learning strategies produce learning outcomes such as changes and adjustments in the knowledge base, organizational structure, and functioning of the governance regime as part of the emerging learning culture (Newig et al., 2010; Siebenhüner, 2008).

2.1 Research objective and questions

This paper’s objective is to better understand how the UNFCCC multilateral process, including the Paris Agreement, enables multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation and how it could be enhanced. The analysis of this is guided by the following questions:

-

(i)

How does the institutional design of adaptation under the UNFCCC enable multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation?

-

(ii)

What learning strategies have been adopted and how they can contribute to multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation under the UNFCCC?

-

(iii)

How does the UNFCCC regime understand the contribution of multi-level learning for adaptation outcomes?

3 Methods

Qualitative research methods have been applied for the thematic analysis of UNFCCC documentation, complemented by interviews and personal observations of UNFCCC adaptation negotiations and the Paris Agreement. The study’s timeframe covers 2001 to 2020, thus starting with the adoption of the Marrakesh accord that sparked the initiation of adaptation working plans in the UNFCCC context. This period is long enough to track relevant evolutions of multi-level learning and its enabling factors.

The analysis focuses on multi-level learning originating at the global level and linked to the UNFCCC multilateral process, such as processes conducted and followed up by UNFCCC bodies and expert groups. As further explained below, examining multi-level learning originating from the global process does not exclude learning taking place at other governance levels. Within the UNFCCC, the global and national levels are represented by default in a multi-level setting, given that the Parties are the constituencies of the UNFCCC process itself and the UNFCCC process has put in place the mechanism to learn from experiences acquired across different levels of governance.

Governance levels were defined in the following way: global (e.g., multilateral processes including UNFCCC); international (e.g., international organizations); regional (involving regional organizations and institutional arrangements, including geographic regions, e.g., the Andean region); national (e.g., national policy processes); and the local levels, including local governments and communities.

Our research design with a focus on the global institutional setting has certainly limitations for tracking multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation across levels of governance. First, we assume adaptation across levels of governance is still strongly defined by UNFCCC rules and orientations. In particular, this omits important contextual information at local/national/regional levels that likely involve an even greater diversity of actors and networks. Furthermore, we cannot do a proper analysis of learning outcomes at the levels where they matter most—nationally and locally without more extensive field work at these levels.

3.1 The data

The primary data sample comprises 45 documents and 6 interviews with key players at the multilateral level, selected though purposive sampling (Robinson, 2013) to complement the analysis with additional empirical data and personal notes of direct observations of UNFCCC negotiations and body meetings included in “Appendix 1”. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Documents for analysis were selected via systematic sampling methods (Koerber & McMichael, 2008); this involves including backbone documents, but also being open to new leads that may emerge during the analysis and consolidating the sample through the saturation of additional qualitative information during the data coding process. The document sample includes key Conference of the Parties (COP) decisions; reports of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI), the Adaptation Committee (AC), and the Least Developed Countries Expert Group (LEG); international workshop proceedings; and other selected reports and data (see Table 1 for an overview and “Appendix 1” for the extensive list of reference documents).

3.2 The analysis

The document analysis combines elements of content and thematic analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). The analytical framework was refined through an interactive hybrid process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis integrating data-driven codes with theory-driven codes. The theory provided the thick structure of the analytical framework, but not the specific terminology as this was adapted to better link to the multi-level learning process in the UNFCCC context. Thus, the resulting coding tree (see “Appendix 2”) maintains the analytical framework's key concepts and logic sequence but integrates additional categories resulting from inductive coding.

As learning is not a term frequently used in the reviewed documents, we have applied the wisdom hierarchy (Rowley, 2007) or DIKW model—data, information, knowledge, and wisdom—to identify learning categories and codes.

4 Results

The results are presented according to the three research questions and aligned with each element of the analytical framework.

4.1 Enabling factors

The structure of UNFCCC institutional arrangements on adaptation includes UNFCCC bodies like the COP and the subsidiary bodies – SBSTA and SBI; the UNFCCC Secretariat and the AC; various institutionalized groups of experts, alliances, and partnerships with organizations outside the Convention; established knowledge platforms and institutionalized workshops and gatherings taking place at the global and regional levels and other arrangements oriented towards providing services for the dissemination of information and knowledge products (see “Appendix 4”).

Four COP decisions described below provide the backbone for adaptation under the Convention (see “Appendix 3” for a detailed description of these COP decisions), each of them having potential to enable multi-level learning.

The least developed countries (LDC) work programme, adopted at COP 7 in 2001, was designed to address the special needs of LDCs regarding funding and technical assistance. The LDC work programme has served, among other things, to organize national capacities, international funds, and technical assistance for adaptation, including guidance for the application of National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs) in LDC facilitated by the LEG (D28/CP.7; D29/CP.7; LEG 35 para 3).

In 2006, SBSTA adopted the Nairobi Work Programme (NWP) on impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation to climate change at COP 11, as a five-year programme to enhance understanding, knowledge sharing, and collaboration on adaptation (D2/CP.11 ANNEX para 2), which are key enabling factors of multi-level learning. The NWP, after evaluation, received a renewed mandates under the CAF and the Paris Agreement. As described in more detail below, the NWP has engaged a broad range of organizations to contribute their knowledge and experiences to adaptation efforts worldwide and thus to multi-level learning.

With the CAF (COP 16) and the Paris Agreement (COP 21), the UNFCCC established the guidance for countries to take on “enhanced actions and international cooperation on adaptation”. The CAF states that Parties put in place the “institutional capacities and enabling environments for adaptation” (D1/CP.16 para.14 c). It invites all developing countries other than LDCs to put in place National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and defines the functions of the AC and the LEG to promote, in a coherent manner, the implementation of adaptation and reporting progress to both subsidiary bodies yearly.

The Paris Agreement, for its part, put in place the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) as a central mechanism to make progress towards its goal (PA, Art. 2). With NDCs, countries are encouraged to establish adaptation priorities and means for implementation, considering the institutional capacities and enabling environments for adaptation put in place by the CAF. To guide the implementation of NDCs, at COP 24 in 2018, Parties agreed on a set of rules (the Katowice climate package) including the operation of a public adaptation-efforts registry maintained by the secretariat and additional provisions for the AC and the LEG to enhance the coherence of the work on adaptation, including the institutional arrangements for finance, technology development, and transfer, and capacity building in line with their mandates (CMA.1, decisions 10/CMA.1 and 11/CMA.1).

Two important sets of modalities for adaptation were established in the NWP (D2/CP.11 Annex VI) and the Katowice climate package (CMA. 1). These include basic working modalities such as workshops and gatherings, expert groups, reporting modalities, submissions, and web-based repositories. The Katowice climate package, for its part, defines a set of rules guiding NDC implementation, including the reporting and registry of Parties’ adaptation activities and the support provided to, and received by, Parties.

Analysing the UNFCCC mandate and institutional arrangements through a multi-level learning lens led to the identification of a network of multi-level learning nodes (see Fig. 2) further described below.

Multi-level learning nodes and networks: The figure captures multi-level learning nodes with a scope of several governance levels and relevance to different UNFCCC decisions. The overlaps of different dotted spaces denote networks and interactions. A short description of each of the institutional arrangements included in the figure and their respective acronym is listed in “Appendix 4”

Multi-level learning has been enabled on one side through horizontal coordination, which has become more sophisticated with the deployment of the adaptation regime under the UNFCCC. Horizontal coordination was initially prompted by the interactions of the two subsidiary bodies SBSTA and SBI with SBSTA overseeing and conducting the adaptation agenda under the NWP (SBSTA 25 para. 15), and SBI guiding the LEG and the LDC work programme to ensure that LDC adaptation needs are adequately addressed. The SBSTA has also promoted coordination with other bodies and organizations under and outside the Convention—for example, introducing and disseminating the results of science to the NWP process in coordination with the IPCC—but also inviting other UN system bodies to introduce other important considerations and synergies into the NWP process (e.g. SBSTA 29, para. 85).

The LDC work programme itself is a node of multi-level learning (Fig. 2) in which the experiences of LDCs and the LEG on the implementation of NAPAs across local, national, and global levels have been gathered. With the Paris Agreement, the LEG is expected to assume a more prominent role, disseminating the experiences gathered by the implementation of NAPAs in the new context of more widely adopted NAP implementation processes (Report LEG 2020 para. 11; AC-SB 39 para. 24–25).

The AC and the NAP task force (central in Fig. 2) also form a multi-level learning node, putting in place the institutional arrangements and capacities for adaptation planning through NAPs and promoting and sharing experiences on adaptation across governance levels. The AC (D2/CP.17 para. 92–93) has become central in the coordination with relevant organizations at different governance levels, including with both subsidiary bodies by the identification of concrete opportunities for scaling up adaptation (D1/CP.21 para 124, 128).

The NAP task force has the potential to prompt multi-level learning through national implementation (AC-SB 47; AC-SB 47 para 51), technical assistance provided by NAP task force members and outreach events like NAP Expos. However, the empirical base around NAPs is still limited as stated by one of the interviewees. While the NAP mechanism was approved in 2010 in Cancun, financing was only available in 2016 once the GCF became operational, so the countries are only beginning to have very initial experiences with their NAPs (I4).

Another feature supported by the structure of mandates and institutional arrangements is cross-level interactions with the intention to encourage learning from Parties’ and other stakeholders’ experiences gathered from adaptation actions and policies across different levels of governance. The NWP (Fig. 2 left) has triggered multi-level learning through action pledges proposed by partner organizations implemented at different governance levels and facilitated by active stakeholder engagement, established register procedures, and the focal point forum oriented to learning from experiences generated in the context of the NWP (e.g., SBSTA 25 para. 17; SBSTA 28 para 13; SBSTA 30 para.13).

The catalytic role of the NWP for enhanced action on adaptation has been frequently underscored (e.g., SBSTA 29 para 14). For example, at the end of the first five-year period of the NWP, SBSTA recorded 136 NWP partner organizations and 84 submitted action pledges (SBSTA 30 para. 13). Three years later, the number had almost doubled to 265 NWP partner organizations and 175 action pledges (SBSTA 37 para. 13). The continuous engagement of different types of organizations, including underrepresented stakeholders such as indigenous groups (SBSTA 33 para. 15) has the potential to produce relational forms of multi-level learning. Nevertheless, as stated by an advocate interviewed—raising the voices of the most vulnerable are still high on the agenda of observer organizations (I1).

4.2 Learning strategies

In the case of learning strategies, we identified eight categories included in Fig. 3.

Learning strategies: This figure includes the eight (see numbering) learning strategies resulting from the coding of the data. The dotted lines schematically describe a space defined by the governance levels and the cognitive, normative, and relational dimensions of multi-level learning related to each learning strategy (one colour associated with one strategy)

Making relevant information available at different governance levels is a central learning strategy on adaptation in the UNFCCC such as the collection and generation of data and information (1) on impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation (D2/CP.11 ANNEX para 2). Parties have often been encouraged to share relevant information (2) on impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation and to include that information in official reports and dissemination and public awareness efforts. The UNFCCC secretariat the Global Environmental Facility and other UN agencies are often requested to compile and share relevant information to advice negotiations and decision-making at different governance levels. The interviewees recognize information and knowledge sharing as a central and continuous strategy applied to promote learning (e.g. I1, I6).

Analysing information and knowledge gaps and needs (3) is another strategy formally used at different governance levels. Parties are encouraged to report on gaps and needs concerning information, knowledge, and other means of implementation (e.g. LEG 35, pp.26–27). Regarding the learning needs of different groups, the Lima Adaptation Knowledge Initiative (LAKI) put in place regional dialogues with Parties and other stakeholders to identify knowledge barriers that impede the implementation and scaling up of adaptation action. A former AC member recognised the role of the NWP in gathering and sharing relevant information “however everybody sharing information in web repositories can produce an info-dump, there is a need of other strategies to encourage learning” (I6, 18’-19’).

The UNFCCC bodies and other partner organizations are often requested to provide guidance (4) for putting in place concrete adaptation actions and better planning, monitoring, and evaluation of adaptation policy measures (e.g. Report LEG 2020). As stated by an international NGO interviewed—the learning challenges emerge by the adoption of different adaptation policy approaches (I5). Additional guidance and training is needed to facilitate the adoption of policy measures, those processes have often drawn on knowledge from groups of experts (5) in charge of compiling the best knowledge available, experiences, good practices, and lessons learned for preparing and refining guidelines, methods, and tools adjusted to national circumstances (e.g., PA Art. 2 para 2). In these cases, training activities (6) and validation with the engagement of different stakeholders across governance levels is a frequently used learning strategy.

The application of policy measures and actions (7) requires a set of cognitive, normative, and relational features and the engagement of different types of stakeholders, including the local communities and thus multi-level learning. Conducted activities to exchange knowledge, experiences, and views (8) are desired in formats that allow dialogue and mutual learning across levels of governance, because such a process has the potential to better engage stakeholder participation and ownership.

More and more, there is a tacit recognition of the importance of local and indigenous knowledge, in addition to scientific knowledge, for applying and disseminating adaptation actions and good practices at the local and national levels, and engaging different views for policy design and scaling up solutions (D1/CP.16 para. 12). However, despite the recognition of the role of different types of knowledge, the data also signal remaining constraints, due to power asymmetries, and the lack of effective collaboration and mutual learning among the stakeholders. In the context of NAPs, for example, training provided by international organizations at the national and local levels has been confronted with the limited appropriation, stewardship of national actors for more integrative approaches and policy alignment” (I5, 28’).

4.3 Learning outcomes

The UNFCCC text repeatedly portrays expectations that information and knowledge sharing on adaptation will lead to a better understanding of the causes and risks of climate change. The NWP, for example, is formulated in terms of improving “their understanding and assessment of impacts, vulnerability, and adaptation” and making “informed decisions on practical adaptation actions and measures” (see D2/CP.11 ANNEX para 1). The LDC work programme also underscores similar expectations, calling for “research programmes on climate variability and climate change, oriented towards improving knowledge of the climate system” (D5/CP.7 para 7 vi).

At the end of the first phase of the NWP, Parties recognized progress on the first part of the work programme’s objective, which focuses on improving understanding (and thus learning), but saw less progress in the NWP’s second part:practical adaptation actions and measures (NWP Report 2008 para 16). The interviews underlined the fact that adaptation has become a priority in the last ten years and thus it is not surprising that adaptation has recently started to gain the needed momentum (e.g. I4, I6).

The scaling up of adaptation actions is another outcome that can be linked to multi-level learning. Parties have adopted the CAF’s enhanced action on adaptation (e.g., D1/CP.16 para.12) and enhanced ambition (e.g. PA Art. 6 para 8a), referring to the scale of implementation needed for adaptation to be effective across different levels of governance.

It is interesting to note that the changes in the discourse and approach towards adaptation in UNFCCC have removed some of the barriers to multi-level learning. Scholars have, for example, referred to the COPs in Copenhagen and Cancun as game changing in the North–South relations (Freestone, 2010; Hourcade et al., 2015), previous negotiations marked by strong divide among developed and developing countries, considered one of the major barriers to more open dialogue, multi-level collaboration, and learning (Depledge, 2006).

The CAF is the central instrument for promoting enhanced actions on adaptation, envisioned to be accomplished with a series of measures including the role and functions of the AC (D1/CP.16 para. 20) and the formulation of NAPs (D1/CP.16 para. 15–16). NAPs are oriented to facilitate policy replication through peer learning and technical assistance (AC-SB 41 para. 84). The interviews underscore the NAP process function as a learning vehicle putting in place additional capacities at the country level for fostering adaptation (e.g. I2, I5, I6). As explained by an officer of a multilateral fund—the NAP is oriented to build on adaptation capacities already in place at the country level and reinforce those capacities mainstreaming adaptation in priority sectors and territories (I3).

The design and functions of institutional arrangements are expected to play a significant role in ensuring the coherence and effectiveness of adaptation policies (e.g., D2/CP.11 ANNEX para 2 (a); D1/CP.21 para 125; AC-TP2014 p. 9) which is an important outcome of multi-level learning. The CAF and the Paris Agreement put additional emphasis on reinforcing the global governance of adaptation, including the institutional arrangements, funding, and technical assistance to conduct the process (D1/CP.16; PA art.7). A former AC member interviewed states that there is “a need to enhance the coherence of different adaptation efforts, perceived as going in different directions, the CAF provided the orientation towards a more coherent process” (I6, 12’-13’). For example, the evaluation of implemented adaptation projects can trigger learning linked to the capacities needed for better planning of adaptation across sectors as stated by a multilateral fund officer interviewed: “One of the lessons learned by the fund is that in addition to the capacities needed to withstand the impacts of climate change funded by the projects, we can use the projects to build resilience—adaptation is rather cross-cutting integrated across different sector activities” (I2, 15´-17´).

Another expected outcome of multi-level learning identified in the data is the need to increase the capabilities for innovation about adaptation across different levels of governance. The reports of the AC recognize that innovation capabilities can be enhanced by “striving to reinforce the interface between science, policy, and practice…” (AC-SB 49 para. 55). This collaboration, between actors, across science, policy and practice, is expected to contribute to the “sharing of data between relevant actors, encourage policy learning related to best practices and common issues, and reallocate resources from operations and maintenance to innovation and addressing complex problems” (AC-TP2017 para 32). Other references stress that innovation capabilities can be enhanced by facilitating public–private partnerships, introducing corporate-driven R&D, and facilitating endogenous development of technologies through national innovation systems, using the existing channels for the dissemination of good practices.

5 Discussion

The objective of this paper is to understand how the UNFCCC enables multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation and how it could be enhanced. We chose to review the UNFCCC multilateral process of adaptation as an entry point to analyse multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation across levels of governance. The analysis carried out provides empirical evidence about the enabling factors for multi-level learning in the UNFCCC adaptation regime, the learning strategies adopted, and the way the UNFCCC regime understands the contribution of multi-level learning in relation to adaptation outcomes. Learning outcomes as expected by the UNFCCC are analysed according to criteria highlighted in social and policy learning literature as presented in Sect. 2.

The paper describes multi-level learning originating at the global level and raises questions about its implications across other levels of governance. According to our data, there is a clear recognition in official documents and interviews about the importance of adaptation learning in the UNFCCC context, for example, the role of the NWP contribution to the understanding of the potential impacts of climate change beyond science involving different type of stakeholders across levels of governance, as well as the potential role of the NAP process triggering policy learning across levels of governance. Moreover, the same data show the need for enhanced institutional coherence and effectiveness of the current adaptation regime to address its goals and fulfil its mandate.

Environmental governance and organizational learning scholars recognize multi-level learning as a key functionality of governance settings to enhance resilience and adaptive capacity (Gerlak & Heikkila, 2019; Pahl-Wostl, 2009; Siebenhüner, 2008). One of the central questions underscored by these scholars has been how to maximize, through institutional design, the adaptive capacity of human societies, bearing in mind likely but relatively unknown impacts of global environmental change (Armitage, 2005; Huntjens et al., 2012). These scholars have also argued that the performance of the governance system in terms of adaptation is an indication of its resilience and adaptive capacity (e.g. Adger et al., 2005; Plummer & Armitage, 2010).

The analytical framework applied for this purpose resonates with a scholarly discussion about the factors and outcomes of learning in environmental governance settings (Armitage et al., 2018; Baird et al., 2014; Gerlak & Heikkila, 2011; Sanderson, 2002). Looking at the outcomes of the process brings us to the discussion about learning loops frequently mentioned in the learning literature (e.g. Gupta, 2016; Pahl-Wostl, 2009).

Our research fits within this broader discussion, the data gathered provide relevant examples of the potential adjustments needed at the level of institutional design in the international adaptation regime for enhancing multi-level learning, like for example further facilitating the opportunities of developing countries stakeholders and networks to learn from adaptation elsewhere; the importance to design multi-level learning to trigger catalytic transformation towards enhanced resilience and the scaling up of adaptation across levels of governance; the roll of multi-level learning in planning and evaluating adaptation across levels of governance.

6 Conclusions

Given the objective and questions of this research, one central conclusion is that analysing the enabling factors and outcomes of multi-level learning is a good entry point for understanding the potential, orientation, and learning loops of such learning as suggested by the concerned literature (e.g. Armitage et al., 2018; Pahl-Wostl, 2009). The three elements of our analytical framework, i.e. enabling factors, learning strategies and learning outcomes, provide a comprehensive picture of multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation, including a better understanding of the cognitive, normative, and relational dimensions of such learning and its orientation towards enhanced performance to achieve desired outcomes.

Applying a multi-level learning lens to questions of institutional design opens the possibility to look at the dynamic of the social network, negotiations among different groups, and collaboration processes as the necessary elements for enhanced adaptive capacity across levels of governance. The identified factors are key for enhancing the performance of the governance system, achieving adaptation policy goals like adaptive capacity and resilience.

A fundamental assumption for our (and future) research is that learning can be assessed through changes in governance and its performance for achieving desired outcomes. However, given the complexity of the UNFCCC adaptation regime, it is difficult to attribute the changes and adjustments in the governance system solely to multi-level learning.

It was not within the scope of the paper to determine evidence for what learning has been gained across levels, due to the multilateral adaptation regime. The paper was rather oriented to analyse the institutional design as an enabling factor of multi-level learning. A legal–technical analysis of the text of adaptation under the UNFCCC and the PA was a necessary entry point to assess multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation. The analysis of UNFCCC documents over a considerable time span provided the basis for tracking the evolution of the adaptation regime and its potential to bring multi-level learning. Nevertheless, we consider it is essential to do further analysis at other levels of governance, testing our principal findings and assumptions about multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation and how this plays out in practice over time.

Future research can aspire to assess the outcomes of multi-level learning as applied across levels of governance, including the national and local levels; and obtain additional empirical evidence about how and (how well) multi-level learning nodes work concerning adaptation policy processes and achieving adaptation goals.

References

Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., & Tompkins, E. L. (2005). Successful adaptation to climate change across scales. Global Environmental Change, 15(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.12.005

Appelbaum, S. H., & Goransson, L. (1997). Transformational and adaptive learning within the learning organization: A framework for research and application. The Learning Organization, 4(3), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696479710182803

Armitage, D. (2005). Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. In Environmental Management (Vol. 35, Issue 6, pp. 703–715). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0076-z.

Armitage, D. (2008). Governance and the commons in a multi-level world. International Journal of the Commons, 2(1), 7–32.

Armitage, D., Dzyundzyak, A., Baird, J., Plummer, R., & Schultz, L. (2018). An approach to assess learning conditions, effects and outcomes in Environmental Governance. Environmental Policy and Governance, 28 (1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1781

Baird, J., Plummer, R., Haug, C., & Huitema, D. (2014). Learning effects of interactive decision-making processes for climate change adaptation. Global Environmental Change, 27(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.019

Böhmelt, T., Koubi, V., & Bernauer, T. (2014). Civil society participation in global governance: Insights from climate politics. European Journal of Political Research, 53(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12016

Capello, R., & Faggian, A. (2005). Collective learning and relational capital in local innovation processes. Regional Studies, 39(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320851

Collins, K., & Ison, R. (2009). Jumping off Arnstein’s ladder: Social learning as a new policy paradigm for climate change adaptation. Environmental Policy and Governance, 19(6), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.523

de Coninck, H., Revi, A., Babiker, M., & Bertoldi, P. (2018). Strengthening and implementing the global response. In Global Warming of 1.5 C an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/15516/

Conzelmann, T. (1998). “Europeanisation” of regional development policies? linking the multi-level governance approach with theories of policy learning and policy change. European Integration Online. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.302723

Depledge, J. (2006). The opposite of learning: Ossification in the climate change regime. In Global Environmental Politics (Vol. 6, Issue 1, pp. 1–22). MIT Press Journals. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2006.6.1.1

Dewulf, A., Meijerink, S., & Runhaar, H. (2015). Editorial: The governance of adaptation to climate change as a multi-level, multi-sector and multi-actor challenge: A European comparative perspective. Journal of Water and Climate Change, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2014.000

di Gregorio, M., Fatorelli, L., Paavola, J., Locatelli, B., Pramova, E., Nurrochmat, D. R., May, P. H., Brockhaus, M., Sari, I. M., & Kusumadewi, S. D. (2019). Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Global Environmental Change, 54, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.003

Dovers, S. R., & Hezri, A. A. (2010). Institutions and policy processes: The means to the ends of adaptation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(2), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.29

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

Freestone, D. (2010). From Copenhagen to Cancun: Train Wreck or Paradigm Shift? Environmental Law Review, 12(2), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1350/enlr.2010.12.2.081

Fünfgeld, H. (2015). Facilitating local climate change adaptation through transnational municipal networks. In Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability (Vol. 12, pp. 67–73). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.10.011

Gerlak, A. K., & Heikkila, T. (2019). Tackling key challenges around learning in environmental governance. In Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning (Vol. 21, Issue 3, pp. 205–212). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1633031

Gerlak, A. K., & Heikkila, T. (2011). Building a theory of learning in collaboratives: Evidence from the everglades restoration program. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(4), 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq089

Gonzales-Iwanciw, J., Dewulf, A., & Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. (2020). Learning in multi-level governance of adaptation to climate change–a literature review. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 63(5), 779–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1594725

Gonzales-Iwanciw, J., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S., & Dewulf, A. (2021). Multi-level learning in the governance of adaptation to climate change—the case of Bolivia´s water sector. Climate and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1785830

Gupta, J. (2016). Climate change governance: History, future, and triple-loop learning? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.388

Hackmann, B. (2016). Regime learning in global environmental governance. Environmental Values, 25(6), 663–686. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327116X14736981715625

Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

Henderson, G. M. (2002). Transformative learning as a condition for transformational change in organizations. Human Resource Development Review, 1(2), 186–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/15384302001002004

Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. N. (2010). Types of Multi-Level Governance. In H. Enderlein, S. Wälti, & M. Zürn (Eds.), Handbook on multi-level governance (Issue 11). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849809047.00007

Hourcade, J. C., Shukla, P. R., & Cassen, C. (2015). Climate policy architecture for the Cancun paradigm shift: Building on the lessons from history. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15(4), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9301-x

Huitema, D. A, Cornelisse, C. A, & Ottow, B. B. (2010). Is the jury still out? toward greater insight in policy learning in participatory decision processes-the case of dutch citizens’ juries on water management in the rhine basin. Ecology and Society, 15(1). http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss1/art16/

Huntjens, P., Lebel, L., Pahl-Wostl, C., Camkin, J., Schulze, R., & Kranz, N. (2012). Institutional design propositions for the governance of adaptation to climate change in the water sector. Global Environmental Change, 22(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.015

Jabeen, H., Johnson, C., & Allen, A. (2010). Built-in resilience: Learning from grassroots coping strategies for climate variability. Environment and Urbanization, 22(2), 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247810379937

Koerber, A., & McMichael, L. (2008). Qualitative Sampling Methods. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651908320362

Lesnikowski, A., Ford, J., Biesbroek, R., Berrang-Ford, L., Maillet, M., Araos, M., & Austin, S. E. (2017). What does the Paris Agreement mean for adaptation? Climate Policy, 17(7), 825–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1248889

Minx, J. C., Callaghan, M., Lamb, W. F., Garard, J., & Edenhofer, O. (2017). Learning about climate change solutions in the IPCC and beyond. Environmental Science and Policy, 77, 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.014

Naess, L. O. (2013). The role of local knowledge in adaptation to climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 4(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.204

Newig, J., Günther, D., & Pahl-Wostl, C. (2010). Synapses in the network: Learning in governance networks in the context of environmental management. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 24. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03713-150424

Okereke, C., Bulkeley, H., & Schroeder, H. (2009). Conceptualizing climate governance beyond the international regime. Global Environmental Politics. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2009.9.1.58

Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19(3), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.06.001

Pauw, W. P., & Klein, R. J. T. (2020). Beyond ambition: Increasing the transparency, coherence and implementability of Nationally Determined Contributions. Climate Policy, 20(4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1722607

Pelling, M., High, C., Dearing, J., & Smith, D. (2008). Shadow spaces for social learning: A relational understanding of adaptive capacity to climate change within organisations. Environment and Planning A, 40(4), 867–884.

Plummer, R., & Armitage, D. (2010). Integrating perspectives on adaptive capacity and environmental governance (pp. 1–19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12194-4_1

Pörtner, H., Roberts, D., Adams, H., Adler, C., & Aldunce, P. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2679314/climate-change-2022/3702620/

Reed, M. S., Evely, A. C., Cundill, G., Fazey, I., Glass, J., Laing, A., Newig, J., Parrish, B., Prell, C., Raymond, C., & Stringer, L. C. (2010). What is social learning? Ecology and Society, 15(4): r1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03564-1504r01

Rietig, K. (2019). Leveraging the power of learning to overcome negotiation deadlocks in global climate governance and low carbon transitions global climate governance and low carbon transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(3), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1632698

Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

Rowley, J. (2007). The wisdom hierarchy: Representations of the DIKW hierarchy. Journal of Information Science, 33(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551506070706

Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21(2–3), 129–168.

Sanderson, I. (2002). Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Administration, 80(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00292

Sandström, A., Söderberg, C., & Nilsson, J. (2020). Adaptive capacity in different multi-level governance models: a comparative analysis of Swedish water and large carnivore management. Journal of Environmental Management, 270, 110890. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2020.110890

Siebenhüner, B. (2008). Learning in International Organizations in Global Environmental Governance. Global Environmental Politics. file:///C:/Users/Javier/Downloads/Siebenhubner.pdf

Tschakert, P., & Dietrich, K. A. (2010). Anticipatory learning for climate change adaptation and resilience. Ecology and Society, 15(2), art11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03335-150211

Vink, M. J., Dewulf, A., & Termeer, C. (2013). The role of knowledge and power in climate change adaptation governance: a systematic literature review. Ecology and Society, 18(4), art46. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05897-180446

Vinke-de Kruijf, J., & Pahl-Wostl, C. (2016). A multi-level perspective on learning about climate change adaptation through international cooperation. Environmental Science and Policy, 66, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.07.004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 2.

Interviews

I1 | International NGO (Observer) | 25/10/2021 |

I2 | Multilateral fund | 10/11/2021 |

I3 | Multilateral development bank | 16/11/2021 |

I4 | International NGO (Observer) | 01/07/2022 |

I5 | International NGO (Observer) | 21/07/2022 |

I6 | Multilateral fund and former AC member | 19/08/2022 |

Personal notes and participation in observer reports

P1 | AC 18RINGO Report | RINGO Report of the observer group to the 18th meeting of the Adaptation Committee. |

P2 | CAS 2021 | Climate Adaptation Summit hosted by the Netherlands 25–26 January 20021, Personal Notes |

Appendix 2

See Table 3.

Appendix 3

See Table 4.

Appendix 4

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzales-Iwanciw, J., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. & Dewulf, A. How does the UNFCCC enable multi-level learning for the governance of adaptation?. Int Environ Agreements 23, 1–25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-023-09591-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-023-09591-0