Abstract

The need for characterization of thermophysical properties of steel was addressed in the FFG-Bridge Project 810999 in cooperation with our partner from industry, Böhler Edelstahl GmbH & Co KG. To optimize numerical simulations of production processes such as plastic deformation or remelting, additional and more accurate thermophysical property data were necessary for the group of steels under investigation. With the fast ohmic pulse heating circuit system and a commercial high-temperature Differential Scanning Calorimeter at Graz University of Technology, we were able to measure the temperature-dependent specific electrical resistivity and specific enthalpy for a set of five high alloyed steels: E105, M314, M315, P800, and V320 from room temperature up into the liquid phase. The mechanical properties of those steels make sample preparation an additional challenge. The described experimental approach typically uses electrically conducting wire-shaped specimen with a melting point high enough for the implemented pyrometric temperature measurement. The samples investigated here are too brittle to be drawn as wires and could only be cut into rectangular specimen by Electrical Discharge Machining. Even for those samples all electrical signals and the temperature signal can be recorded with proper alignment of the pyrometer. For each material under investigation, a set of data including chemical composition, solidus and liquidus temperature, enthalpy, electrical resistivity, and thermal diffusivity as a function of temperature will be reported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

For about 70 % of all industrially formed metal parts, the production starts with the liquid metal/alloy [1]. Computer-based simulations allow modeling of casting, melting and remelting processes, heat transport, solidification shrinkage, residual stress, heat treatment, welding, forging, rolling, and cutting or even predictions of microstructures. A key limitation to the successful introduction of these models is the lack of thermophysical data required as input parameters for simulation tools. Thus, experimentally obtained thermophysical property data of pure metals and also of binary and multi-alloy systems are of great importance. More accurate property data will lead to a better scientific understanding of liquid metals and alloys and improve the results of numerical simulation tools for optimizing metallurgical processes.

For this study a set of five high alloyed steels, optimized for different applications, was chosen: E105—used in aviation, M314 and M315—steels for plastic molds, P800—a steel for automotive parts with soft magnetic behavior, and V320—representing heat treatable steels. The chemical compositions (chemical analysis performed by Böhler Edelstahl GmbH & Co KG) are listed in Table 1, and some typical applications of the different steels are summarized in Table 2 and described in more detail in the data sheets [2,3,4,5,6].

2 Experimental Apparatus and Procedures

2.1 Sample Preparation

All the samples for the density, pulse heating, and calorimetric measurements were machined from one large cylinder of each material. The typical chemical composition and also the actual analysis for each material are listed in Table 1. For the density measurements, a part of the initial cylinder was cut and machined to size.

For the calorimetric measurements, the sample size was mainly informed by the crucible size. The disk-shaped samples were also machined from a slice of the larger block and had typical dimensions of 5.2 mm \(\times \) 0.5 mm (diameter \(\times \) height).

The samples for the pulse heating experiments had a rectangular cross section (nominal: 0.5 mm \(\times \) 0.5 mm, 70 mm length), as the raw material was too hard and brittle to be drawn into a wire. The initially machined thin plate was sliced into multiple samples by Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM).

After machining, all samples were cleaned with acetone and received no further treatment.

2.2 Pulse Heating Setup with \(\upmu \hbox {s}\) Resolution

Each specimen was clamped into a sample holder and then resistively volume heated as part of a fast capacitor discharge circuit. A nitrogen atmosphere with 0.5 bar above ambient pressure was maintained for all measurements. With sub-\(\upmu \hbox {s}\) time resolution, the current through the specimen was measured with a Pearson probe [7], the voltage drop across the specimen was determined with knife-edge contacts and subsequent voltage dividers, and the radiance temperatures of the samples were detected with an optical pyrometer operating at 1500 nm. From these combined measurements, the calculated specific heat and mutual dependencies between enthalpy, electrical resistivity, and temperature of the alloys up into the liquid phase are reported in form of polynomial fits. The electronic component of the thermal diffusivity is calculated via the Wiedemann–Franz law.

2.3 Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC)

All DSC measurements were performed on a commercial instrument, a Netzsch DSC 404. Prior to any measurement, a standard 5-point temperature calibration at the melting onset of In, Bi, Al, Ag, and Au was performed [8].

The specific heat capacity \(c_\mathrm{p}\) of the specimen was measured relative to a sapphire reference standard with heating rates of 20 K\(\cdot \hbox {min}^{-1}\), under argon gas flow of 6 l\(\cdot \hbox {h}^{-1}\) and at atmosphere pressure. By integrating these data over temperature T, specific enthalpy \((H_{298})\) as a function of temperature was obtained from room temperature (RT, 298 K) to 1500 K.

2.4 Solidus and Liquidus Temperatures

The solidus \((T_{\mathrm{s}})\) and liquidus \((T_{\mathrm{l}})\) temperatures in Table 3 are reported as determined by Böhler from DTA measurements and Thermocalc calculations. To calibrate the pyrometer in the pulse heating setup, the mean of \(T_{\mathrm{s}}\) and \(T_{\mathrm{l}}, T_{\mathrm{M}}\), is assigned to the middle of the recorded melting plateau at each experiment.

2.5 Density Measurement

All sample densities are determined at room temperature by weighing a machined cylinder in air on a Mettler Toledo PM4800 scale. The cylinders were machined to a typical diameter and height of 50 mm with maximum machine accuracy and then measured with a caliper at multiple points.

2.6 Evaluation of Thermophysical Properties

From the signals recorded with the pulse heating setup, the temperature-dependent current through the sample and the voltage drop across a previously measured length, the enthalpy difference compared to RT values \((H_{298})\) and values for the specific electrical resistivity are computed. Due to the rectangular shape of the samples, the volume expansion measurement based on the specimen’s shadowgraph was not feasible. Therefore, all data for the electrical resistivity are reported in reference to the initial geometry at RT (index IG). In an earlier paper [9], results on volume expansions of wire-shaped samples of a chromium–nickel–molybdenum steel (1.4534) are reported and are supposed to be similar to that of the materials reported here so that it could be used for estimating a corrected electrical resistivity value.

All detailed information on the evaluation and the equations used to compute the electrical resistivity, enthalpy, and heat capacity have been reported in several previous papers [9, 10]. It is important to reiterate that the temperature-dependent electronic component of the thermal diffusivity a is estimated using the Wiedemann–Franz law with the Lorentz number \(L\, (L = 2.45 \times 10^{-8 }\hbox {V}^{2}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-2})\), assuming that L is invariant within the region of interest.

From the right-hand side of Eq. 1, it is evident that thermal diffusivity only depends on the \(c_\mathrm{p}\), density at room temperature \(d_{\mathrm{RT}}\), and electrical resistivity \({\rho }_{\mathrm{IG}}\) at room temperature geometry. Thermal diffusivity is independent of volume expansion and can therefore also be measured for samples with rectangular cross sections. Additional information to our procedures is given in several papers published by our workgroup on different steels and Ni-based alloys [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

3 Measurement Results

The next subsections list the results from the pulse heating and DSC measurements in the form of polynomial fits. Each DSC measurement was repeated four times with a different specimen. The microstructures of the alloys change during the cooling with constant rate and then differ from those of the original materials. Thus, only mean values from the first heating cycle of each sample are reported here to represent the material with the manufacturers initial heat treatment.

In pulse heating, the samples vaporize at the end of each measurement; thus, a new specimen is used each time. The reported polynomials represent mean values of 10, 6, 13, 15, and 11 measurements for E105, M314, M315, P800, and V320, respectively. All other parameters used in the evaluations, namely \(T_{\mathrm{s}}, T_{\mathrm{l}}, T_{\mathrm{M}}\) and density at RT, are summarized in Table 3.

3.1 E105

All measurement results for E105 are summarized in Table 4. During melting, the specific electrical resistivity at initial geometry increased from \(\rho _{\mathrm{IG}}=1.245~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{s}}=1784\hbox { K}\) to \(1.272~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{l}}=1811~\hbox {K}\), resulting in a \(\varDelta \rho \) of \(0.027~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) for this transition.

From the slope of the enthalpy curve, we obtained the corresponding specific heat capacity from pulse heating as \(681\hbox { J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) at the end of the solid phase, and \(753\hbox { J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) in the liquid phase; both values are valid within the stated temperature intervals (see Table 4).

At the melting transition, the specific enthalpy increased by \(\varDelta {H}_{\mathrm{s}} = 282~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) from \(H_{298}=995\hbox { kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) at the solidus, to \(1277\hbox { kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) at the liquidus.

3.2 M314

All measurement results for M314 are summarized in Table 5. During melting, a change in resistivity from \({\rho }_{\mathrm{IG}} = 1.280~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{s}} = 1732~\hbox {K}\) to \(1.294~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{l}} = 1805 \hbox { K}\) was observed, resulting in a \(\varDelta \rho \) of \(0.014~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\).

From the slope of the enthalpy curve, we obtained the corresponding specific heat capacity from pulse heating as \(755~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) for the end of the solid phase, and \(757~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) in the liquid phase; both values are valid within the stated temperature intervals.

At the melting transition, the specific enthalpy increased by \({\varDelta H}_{\mathrm{s}} = 318~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) from \(H_{298} = 1007~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) at the solidus, to \(1325~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) at the liquidus.

3.3 M315

All measurement results for M315 are summarized in Table 6. During the melting transition, a change from \(\rho _{\mathrm{IG}} = 1.260~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{s}} = 1767~\hbox {K}\) to \(1.280~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{l}} = 1806~\hbox {K}\) was observed, resulting in a \(\varDelta \rho \) of \(0.020~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\).

The enthalpy at melting changed between the solidus and liquidus temperature from \(1034~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) to \(1322~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\); thus, an enthalpy of fusion for M315 of \({\varDelta H}_{\mathrm{s}} = 288~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) was obtained.

At the end of the solid phase, the specific heat capacity \(c_{\mathrm{p}}\) was \(775~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\). This number decreased to \(666~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) for the observed temperatures above the liquidus point.

3.4 P800

All measurement results for P800 are summarized in Table 7. During the melting transition, a change in electrical resistivity from \(\rho _{\mathrm{IG}} = 1.265~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{s}} = 1724~\hbox {K}\) to \(1.290~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{l}} = 1747~\hbox {K}\) yielded a \(\varDelta \rho \) of \(0.025~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\).

The enthalpy at melting changed from \(1040~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) to \(1317~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) resulting in an enthalpy of fusion for P800 of \({\varDelta H}_{\mathrm{s}} = 277~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}\).

The corresponding specific heat capacity for the end of the solid phase was \(771~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) and increased during melting to \(885~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) for the liquid phase.

3.5 V320

All measurement results for V320 are summarized in Table 8. During the melting transition, the electrical resistivity with initial geometry changed by \({\varDelta \rho }=0.023~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\), from \(1.279~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{s}} = 1723~\hbox {K}\) to \(1.302~\upmu \cdot \Omega \cdot \hbox {m}\) at \(T_{\mathrm{l}} = 1829~\hbox {K}\).

Specific heat capacities of \(861~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) and \(922~\hbox {J}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\cdot \hbox {K}^{-1}\) were obtained at the end of the solid phase and for the liquid phase, respectively.

The change of enthalpy at the melting transition from \(1030~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) to \(1348~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\) resulted in an enthalpy of fusion of \({\varDelta H}_{\mathrm{s}} = 318~\hbox {kJ}\cdot \hbox {kg}^{-1}\).

4 Discussion

Information on nominal composition for all measured steels is stated in the products data sheets [1,2,3,4,5]. To confirm those numbers, an additional individual analysis was performed for each steel in the laboratory of Böhler, and both data sets are compared and stated in Table 1. Typical applications for each steel are listed in Table 2. The melting ranges \((T_{\mathrm{s}}, T_{\mathrm{l}}, T_{\mathrm{M}})\) and densities at RT are presented in Table 3 for all 5 alloys.

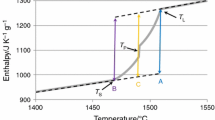

For the steels E105, M314, M315, P800, and V320, the specific enthalpy versus temperature values are plotted in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and were obtained by means of DSC with heating rates of 20 K/s. At the end of the solid phase, these data overlap with data points obtained by pulse heating with significantly higher heating rates of \(10^{8}\) K/s. Only the dataset for V320 shows a slight difference at the onset of the pulse heating data, which vanishes above 1400 K. This difference is caused by a phase transition occurring at about 1050 K that is clearly visible in the measured DSC data, but cannot be resolved with the higher heating rates from pulse heating. Only 200 K higher the data from the two methods are indistinguishable again. These plotted results also support that pulse heating with heating rates of \(10^{8}\) K/s can still be assumed as “quasistatic” if there are no significant phase changes in the solid phase. To our knowledge, processes with heating or cooling rates up to \(10^{10 }\) \(\hbox {K}/\hbox {s}\) can be assumed to be “quasistatic” [19]. A second proof for this assumption is the clearly visible melting plateau for pure elements and the melting transition for alloys between solidus and liquidus.

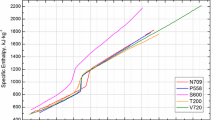

Enthalpy data for all the materials are plotted together in Fig. 6 and show that the individual data sets do not differ by more than \(\sim \)10 % from each other. While \(c_{\mathrm{p}}\) in the liquid phase is a constant value (see also Grimvall [20]), \(c_{\mathrm{p}}\) in the solid phase typically varies with temperature. At the end of the solid phase, we again calculate a constant \(c_{\mathrm{p}}\) value from the linear slope of the enthalpy data.

Resistivities at initial geometry (see Fig. 7) also lie within a narrow band and show a variation of about ±4 % between each other. Nevertheless, each material differs somewhat from the others. In the solid phase, resistivity of all the materials increases. The evident kinks in all the curves represent the transition from solidus to liquidus. In the liquid phase, the values are constant for M314 and M315 and show just a small, but positive, temperature coefficient for the other three alloys.

With the presented results, \(c_{\mathrm{p}}\) from the slope of H(T), resistivity at initial geometry, and the density at room temperature, thermal diffusivity is calculated as a function of temperature according to Eq. 1. A summarizing plot of all thermal diffusivity results is shown in Fig. 8. Thermal diffusivity in the liquid phase increases for all materials. The alloy M315 has the highest values in the liquid phase. For M314 and M315, the plot also shows an increase in thermal diffusivity at the solidus–liquidus transition while it decreased for all the other materials. The decreasing behavior is well known from other materials. Up to now, however, we do not have an explanation for the increasing behavior of the two steels.

In this context, it is important to remember that the calculated thermal diffusivity values presented in this paper are based on electric measurements from pulse heating experiments that do not take into account any lattice contributions, which has already been discussed in an earlier publication [10]. Also Klemens [21] considers electronic and lattice components in his theoretical work regarding thermal conductivity of metals and alloys in the solid state. Klemens reports various values for lattice contributions in Fe–Cr–Ni alloys [22] which can be used as guiding values to correct for the lattice contributions in the solid phase. For the reported values of the liquid phase, no such correction is necessary, as there is no influence from the lattice any more.

4.1 Uncertainties

According to GUM [23], the uncertainties reported in Table 9 are relative expanded uncertainties with a coverage factor of \(k = 2\). The uncertainty bars are depicted within the individual Figures.

The main contribution in the uncertainty budget for the DSC measurements is the repeatability of the signal base line. This variability dominates other effects including the repeatability of the temperature calibration, the sample position in the crucible, and the uncertainty introduced by the reference sapphire. For all presented DSC data, the relative expanded uncertainty increases from 3 % at the lowest temperatures to 4 % at 1500 K.

For the pulse heating circuit, the uncertainties are also strongly dependent on the absolute property value. This is reflected by the varying numbers stated in Table 9 and requires a individual uncertainty budget for each material. Included therein are the contributions from the measurements of: the sample dimensions, pyrometric temperature, current through the sample, and the voltage drop between the knife-edge contacts. It also accounts for the uncertainty in the solidus and liquidus temperature as well as the influence of the accuracy of the used data acquisition card.

A more detailed description of the uncertainty calculations for the DSC and pulse heating measurements is published in previous articles [24,25,26].

References

J. Brillo, Thermophysical Properties of Multicomponent Liquid Alloys, 1st edn. (De Gruyter, Oldenbourg, 2016)

B. Edelstahl, Data sheet E105 (2006). URL http://www.bohler-edelstahl.com/media/E105DE.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6hNwSMgaB. Accessed May 2016)

B. Edelstahl, Data sheet M314 (2005). URL http://www.bohler-edelstahl.com/media/M314DE.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6hNvdrgKz. Accessed May 2016)

B. Edelstahl, Data sheet M315 (2015). URL http://www.bohler-edelstahl.com/media/M315DE.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6hNwiqlaK. Accessed May 2016)

B. Edelstahl, Data sheet P800 (2001). URL www.bohler.nl/dutch/files/downloads/Bohler_VMR.pdf

B. Edelstahl, Data sheet V320 (1993). URL www.bohler.at/english/files/downloads/V320DE.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6hNxGWmll. Accessed May 2016)

Pearson Electronics Inc. Datasheet: Pearson current monitor model 3025 (1999). URL http://www.pearsonelectronics.com/pdf/3025.pdf

ASTM e967-08, standard test method for temperature calibration of differential scanning calorimeters and differential thermal analyzers (2014)

B. Wilthan, H. Reschab, R. Tanzer, W. Schützenhöfer, G. Pottlacher, Thermophysical properties of a chromium-nickel-molybdenum steel in the solid and liquid phases. Int. J. Thermophys. 29(1), 434–444 (2008). doi:10.1007/s10765-007-0300-1

B. Wilthan, W. Schützenhöfer, G. Pottlacher, Thermal diffusivity and thermal conductivity of five different steel alloys in the solid and liquid phases. Int. J. Thermophys. 36(8), 2259–2272 (2015). doi:10.1007/s10765-015-1850-2

A. Seifter, K. Boboridis, V. Didoukh, G. Pottlacher, H. Jäger, Thermophysical properties of Fe64/Ni36 (Invar) above the melting region. High Temp. High Press. 29(4), 411–415 (1997)

A. Seifter, G. Pottlacher, H. Jäger, G. Groboth, E. Kaschnitz, Measurements of thermophysical properties of solid and liquid Fe-Ni alloys. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 102(9), 1266–1271 (1998)

H. Hosaeus, A. Seifter, E. Kaschnitz, G. Pottlacher, Thermophysical properties of solid and liquid Inconel 718 alloy. High Temp. High Press. 33(4), 405–410 (2001)

S. Rudtsch, H.P. Ebert, F. Hemberger, G. Barth, R. Brandt, U. Groß, W. Hohenauer, K. Jaenicke-Roessler, E. Kaschnitz, E. Pfaff et al., Intercomparison of thermophysical property measurements on an austenitic stainless steel. Int. J. Thermophys. 26(3), 855–867 (2005). doi:10.1007/s10765-005-5582-6

B. Wilthan, R. Tanzer, W. Schützenhöfer, G. Pottlacher, Thermophysical properties of the Ni-based alloy Nimonic 80A up to 2400 K. Rare Met. 25(5), 529–531 (2006). doi:10.1016/s1001-0521(06)60093-4

B. Wilthan, K. Preis, W. Tanzer, R. Schützenhöfer, G. Pottlacher, Thermophysical properties of the Ni-based alloy Nimonic 80A up to 2400 K. II. J. Alloy. Compd. 452(1), 102–104 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.11.214

B. Wilthan, R. Tanzer, W. Schützenhöfer, G. Pottlacher, Thermophysical properties of the Ni-based alloy Nimonic 80A up to 2400 K, III. Thermochim. Acta 465(1), 83–87 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.tca.2007.09.006

T. Hüpf, C. Cagran, E. Kaschnitz, G. Pottlacher, Thermophysical properties of Ni80Cr20. Thermochim. Acta 494(1), 40–44 (2009). doi:10.1016/j.tca.2009.04.015

F. Hensel, G. Pottlacher, Marburg an der Lahn, Germany, private communication (1986)

G. Grimvall, Thermophysical Properties of Materials: Enlarged and Revised Edition. Number ISBN-10: 0444544232, ISBN-13: 978-0444544230. North Holland, (1999). ISBN 0444544232

P.G. Klemens, R.K. Williams, Thermal conductivity of metals and alloys. Int. Met. Rev. 31(1), 197–215 (1986). doi:10.1179/imtr.1986.31.1.197

G. Pottlacher, H. Hosaeus, E. Kaschnitz, A. Seifter, Thermophysical properties of solid and liquid Inconel 718 alloy. Scand. J. Metall. 31(3), 161–168 (2002). doi:10.1034/j.1600-0692.2002.310301.x

Bureau International des Poids et Mesures, Commissionélectrotechnique internationale, and Organisationinternationale de normalisation. Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. International Organization for Standardization (1995)

Boris Wilthan, Verhalten des Emissionsgrades und thermophysikalische Daten von Legierungen bis in die flüssige Phase mit einer Unsicherheitsanalyse aller Messgrößen. Ph.D. thesis, Graz University of Technology (2005)

B. Wilthan, Uncertainty budget for high temperature heat flux DSCs. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 118(2), 603–611 (2014). doi:10.1007/s10973-014-3671-0

M. Luisi, B. Wilthan, G. Pottlacher, Influence of purge gas and spacers on uncertainty of high-temperature heat flux DSC measurements. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 119(3), 2329–2334 (2014). doi:10.1007/s10973-014-4329-7

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology. Research supported by Böhler Edelstahl GmbH & Co KG and the “Forschungsförderungsgesellschaft mbH, Sensengasse 1, 1090 Wien, Austria”, Project 810999.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Selected Papers of the 13th International Symposium on Temperature, Humidity, Moisture and Thermal Measurements in Industry and Science.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilthan, B., Schützenhöfer, W. & Pottlacher, G. Thermophysical Properties of Five Industrial Steels in the Solid and Liquid Phase. Int J Thermophys 38, 83 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-017-2220-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10765-017-2220-z