Abstract

One of the great unknowns in language evolution is the transition from unstructured sign combination to grammatical structure. This paper investigates the central — while hitherto overlooked — role of functor–argument metaphor. This type of metaphor pervades modern language, but is absent in animal communication. It arises from the semantic clash between the default meanings of terms. Functor–argument metaphor became logically possible in protolanguage once sufficient vocabulary and basic compositionality arose, allowing for novel combinations of terms. For example, the verb to hide, a functor, could be combined not only with a concrete, spatial entity like food as its argument, but also with an abstract, non-spatial one like anger. Through this clash, to hide is reinterpreted as a metaphorical action. Functor–argument metaphor requires the possibility of term combinability and the existence of compositionality. At the same time, it transcends compositionality, forcing a non-literal interpretation. We argue that functor–argument metaphor led the development of protolanguage into fully-fledged language in multiple ways. Not only did it expand expressiveness, but it drove the development of syntax including the conventionalization and fixation of word order, and the development of demonstratives. Thus, functor–argument metaphor fills in multiple gaps in the trajectory from a protolanguage, with only some terms and simple term combinations, to the elaborate grammatical structures of fully-fledged human languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Metaphor pervades modern language, but it is absent in animal communication. We focus in this paper on one common type of metaphor, functor–argument metaphors that combine, for example, a verb and its subject or object, or a noun and its possessor. These became logically possible in protolanguage once there was sufficient vocabulary and basic compositionality to allow for novel combinations of terms. For example, a concrete, spatial term such as to hide can be combined not only with a concrete entity term such as food, but also with an abstract, non-spatial one such as anger. We argue that this type of metaphor gave rise to many of the features characteristic of fully-fledged languages. Not only did it expand expressiveness, but it drove the development of syntax, regularizing word order and shaping the development of anaphoric demonstratives and articles. In short, we argue that the facility for metaphorical functor–argument combinations was a powerful driving force at the heart of language evolution.

We first define functor–argument metaphors, and offer several arguments for placing their origins in protolanguage. The subsequent section presents the basis for our argument — the fact that arguments that drive metaphorical interpretations cannot be omitted. We then turn to the ways in which increasing use of functor–argument metaphors led to the conventionalization of word order and the development of demonstratives. We go on to survey the continuation of these developments with grammaticalization, turning conventionalised into fixed word order, and semantically-determined overt arguments into syntactically obligatory ones. We round off the paper by highlighting how the study of functor–argument metaphors offers a new understanding of holistic and analytic composition at the dawn of human language, followed by a brief conclusion.

Metaphor in Language

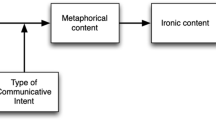

Metaphor arises from the combination of semantically clashing concepts (e.g., Bowdle & Gentner, 2005: pp. 193–199 for a literature review). For example, we defend an argument, even though arguments are not defensible physical locations. Likewise, we arrive at a conclusion, even though no change in location is involved. In these examples and elsewhere in this paper, we address functor–argument combinations: where the functor is a relational term with one or more slots for arguments. In these combinations, metaphors arise when an argument forces a metaphorical reading of the functor because the argument conflicts semantically with selectional restrictions that the functor imposes. For example, the functor arrive by default imposes a selectional restriction on its second argument, namely, that it be a spatial destination. When an argument conclusion is given, this forces an interpretation of arrive with a metaphorical sense, rather than a literal one.

Functor–argument metaphors are ‘proportional’ (or ‘analogical’) metaphors, where A is to B as C is to D (Billow, 1975; Katz, 2017). For example, to arrive at (A) is to a spatial goal (B) as an abstract process (C) is to a conclusion (D). Our argumentation here specifically refers to such proportional metaphors, and the central role they have played in language evolution. The other much-studied type of metaphor is the ‘similarity’ metaphor (Katz, 2017: p. 475 citing Billow, 1975) or A = B metaphor which lacks a functor imposing selectional restrictions on its argument(s). An example is my job is a jail (Bowdle & Gentner, 2005). Unlike proportional metaphors, similarity metaphors allow a part of the equation to be unexpressed and implied, such as in single-word metaphors such as Pig! addressed to a person. Evidence suggests both kinds of metaphor are processed as analogical mappings between the relational systems of base and target (Bowdle & Gentner, 2005).

Functor–argument metaphors are found in all languages, and across all parts of speech (Reinöhl & Ellison, under review). As well as the verb–argument combinations in the above examples, we find (simple or complex) adposition–possessor combinations (in the middle of trouble), noun–possessor combinations (waves of nausea), amongst others. These metaphorical functor–argument combinations played a central role in the development of human language — both in expressivity and in syntax. This paper focuses on their role in the development of syntax.

There has been increasing awareness of the pervasiveness of metaphors in discourse (e.g., Graesser et al., 1989; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Pollio et al., 1977). Metaphors are not at all restricted to poetic language, but pervade all forms of communication. Many metaphors are conventionalised, requiring no creative effort by speakers, as in the example given above: to arrive at a conclusion. Such conventionalised metaphors occur commonly in all genres and registers of language.

Studies of metaphor have shown not only its great productivity, but also its ubiquity across languages. For example, grammaticalization research, which focuses on the historical processes generating grammatical structures, has identified metaphor as a key triggering factor in language after language (e.g., Sweetser, 1990). While there are differences in the precise lexical sources, the construction of metaphors from word combinations with clashing default meanings is universal (e.g., Evans & Wilkins, 2000 on ‘to hear x’ giving rise to cognition concepts like ‘to understand x’ in Australian languages, contrasting with derivations from ‘to see x’ in English and other Indo-European languages).

Metaphors by definition expand our expressive and stylistic options (e.g., Smith & Höfler, 2015, 2017 for an evolutionary perspective), and help us make sense of the abstract world by grounding it in the concrete (e.g., Kovecses, 1988; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Quinn, 1987). This insight is at the heart of cognitive linguistics, and has attracted a great deal of scholarship. What has been overlooked so far, however, is that functor–argument metaphors also affect key grammatical structures, including word order, the encoding of arguments, and the behaviour and role of pronouns — three hallmark grammatical domains of fully-fledged human language. Moreover, we argue that metaphor is what drove the development of these components. We will describe how they developed in response to metaphor, but we start by locating the rise of metaphor in time. From the rise of functor–argument metaphors in protolanguage, a new trajectory shaping and feeding semantic and syntactic complexity begins, a trajectory that brings about important features of modern human language.

Metaphors in Protolanguage

Metaphor pervades modern language, but is absent in animal communication. The great ape Kanzi was reported (Savage-Rumbaugh et al., 1993: pp. 99–100) as bringing a tomato to the ‘mouth’ part of a pumpkin face embedded in a sponge ball when asked to “Feed your ball some tomato”. While this potentially demonstrates a fascinating ability to accommodate loose talk, it seems an instance of play or pretending rather than a case of the analogical metaphors that are the topic of this paper. It is natural to ask, then, at what point metaphor became a feature of language. In this section, we argue that metaphor is, and has been, available in all fully-formed human languages, past and present. If this is the case, then the starting point for metaphor predates modern human languages. Since it is absent in animal communication, it is unlikely that it existed when humans and great apes diverged. Most likely, it developed into a feature of communication in the stage of language evolution called protolanguage, a span linking animal communication and fully-formed human languages.

We continue with a short discussion of animal communication, insofar as it relates to a facility for metaphor. We then turn to the potential for metaphor in protolanguage. While there is no direct evidence for protolanguage having metaphors, as there is no direct evidence for it possessing any linguistic feature, we aggregate a number of arguments in favour of metaphors arising at that stage. These arguments often take the form: if X happened, we would be confident that there were no metaphors in protolanguage, but X did not happen.

(The Lack of) Metaphor in Animal Communication

While there is no evidence for a direct path from primate vocalizations to human language, there is research suggesting that certain primate populations combine calls (e.g., Zuberbühler, 2002). However, we are not aware of any evidence that they use functor–argument metaphors (see Tomasello & Call, 2019 for a recent overview of the state of research into great ape gestures). There are reported instances of chimpanzees using metaphors (Dahl & Adachi, 2013). Whether or not these would pass the test of a strict understanding of the phenomenon, the examples described in these cases do not involve functor–argument combinations. They thus do not fall under the purview of this paper.

If a facility for functor–argument metaphors is not present in animal communication, the simplest hypothesis would be to assume that it arose sometime after our last common ancestor with a language-less relative, such as the bonobo. Based on phylogenetic and paleontological evidence, this places the rise of metaphors sometime within the last 4 million years; after the end of interbreeding between what became the Pan and Homo lineages (Patterson et al., 2006).

Given that functor–argument metaphor is present in all human languages and so probably forms part of a common inheritance, but is not found in non-human communication, the facility for it probably arose in protolanguage, or early in modern human languages. The following sections offer arguments that the development of metaphorical combination occurred in the earlier protolanguage period, rather than in the later period of modern languages.

Logical Availability

One way in which we could rule out functor–argument metaphors as features of protolanguage is if we could be sure that the linguistic machinery needed to construct them was not available. Was it logically possible to construct metaphorical combinations in protolanguage? Earlier, we defined functor–argument metaphors as characterised by semantic clashes between literal meanings and selectional restrictions. Given this definition, we can expect them to arise as soon as the machinery of compositional structure is available. Where there are selectional restrictions, there is the possibility of violating them.

The linguistic machinery needed is: (1) functor–argument combinations, and (2) selectional restrictions. Selectional restrictions are satisfied when a functor and its arguments impose matching semantic constraints. This yields a literal, compositional interpretation of the combination of terms. Where the match fails, i.e., where the terms in their literal senses are not compatible, interpretation may still be achieved by taking the construction metaphorically (e.g., Smith & Höfler, 2015, 2017 on the role of inferential reasoning). Most often, this involves a non-default interpretation of the functor (e.g., interpreting arrive as referring to conceptual change when combining with conclusion). This kind of metaphor thus requires the combinability of terms, and builds on top of compositional combinations, while itself transcending compositionality.

In summary then, the logical apparatus needed to create metaphors is very modest: the ability to create functor-argument combinations with combinatorial semantics as well as inferential reasoning in case of clashing term combinations. It turns out that these exist in animal communication, but without any evidence for clashing, i.e., metaphorical combinations. Campbell’s monkeys (Cercopithecus campbelli) are reported to have combinatorial structure in their calls (Zuberbühler, 2018). Males may give “krak” calls referring to leopards, and “hok” calls referring to eagles. But when these are combined with a suffixed “-oo”, the calls are generalised to meaning a wide range of disturbances (“krakoo”) or general non-ground alerts (“hokoo”). The fact that this generalising “affix” does not occur in isolation does not mean that the construction is not compositional. The English past tense -ed also does not occur in isolation, but is nevertheless part of a compositional construction. Compositionality of meaning, similar to that of the Campbell’s monkey calls, is attested in the complex calls of Japanese tits (Parus minor, Suzuki et al., 2017).

So the compositional and co-restrictive combination of signs can already be seen in the non-human animal world. It is highly likely that this has been a possibility in the ancestor of human language since before the start of the protolanguage period, even if semantically clashing signs only started to be combined from the protolanguage period.

Productivity

Understanding protolanguage involves exploring not just the biological capability of our hominid ancestors to process language, but also the evolution of the system itself. Signalling systems, to the extent that they are not innate, must be learned. Possible features within them will compete against the background of general human learnability and processing constraints (Chater & Christiansen, 2010). Only those successful in competition will survive in future versions of the communication system (Dawkins, 1976; Dennett, 1995). The combination of imperfect reproduction and selection means that the development of language systems is an evolutionary process.

If language evolved to fit the niche of speakers’ minds, then we can expect that there will often be functional explanations for why some linguistic affordances have survived rather than others. Given the focus of this paper, we ask: is functor–argument metaphor use likely to be contagious or not, i.e., would it provide a communicative benefit that would lead to it being repeatedly reproduced? If it is contagious, what benefits does it offer its users?

Functor–argument metaphor use is likely to be contagious, because of one considerable advantage. Metaphors greatly expand the conceptual repertoire of a communication system by making room for the analogical extension of concepts, e.g. where a conclusion can become a ‘place to arrive at’. Having a pattern of responding to metaphor with creative reinterpretation frees the range of possible combinations from the limits of selectional restrictions induced from natural cooccurrence. Metaphor adds a new dimension to the semantic compositionality of language.

For the advantage of these new combinations to be significant, we need the language to have a sufficiently large vocabulary. In a language with only three or four signs, developing a facility for metaphor increases semantic potential by about the same amount as learning a new lexical item. As the number of signs expands, the potential for proportional metaphor grows non-linearly.

Given the advantage offered by metaphors, we expect the facility for them to be a contagious pattern once it arose.

Let us suppose that metaphors did not arise in the protolanguage period, and the facility for them was not contagious. Then we would expect to find modern languages lacking evidence of this facility. Similarly, if a facility for metaphor was contagious, but only arose recently, we might expect to still find languages from isolated places without metaphors. We do not find these gaps.

Thus, we have two more scenarios by which we might have ruled out the rise of a facility for metaphor within the protolanguage period. There is no evidence for either of these scenarios.

Metaphor and Language Diversity

If there were languages that didn’t use functor–argument metaphor at all, this would be an argument against metaphor in protolanguage, as it would suggest a more recent origin. We know of no evidence suggesting that any modern human language lacks metaphor. On the contrary, grammaticalization research, for example, shows metaphor to be an important device across all language families and linguistic areas (e.g., Kuteva et al., 2019). Increasingly, research adds to our knowledge of functor–argument metaphor use in better-studied languages, with insights into the rich use of metaphor in lesser-studied languages.

For example, metaphors for emotional states are traditional in far northern Australian languages (Ponsonnet, 2014). Dalabon (1) shows the use of belly flowing to mean feeling good or nice towards someone.

-

(1) Bulu ka-h-na-n biyi kirdikird

-

3pl 3sg>3-R-see-PR man woman

-

bul-ka-h-marnu-kangu-yowyow.

-

3pl-3sg>3-R-BEN-belly-flow:REDUP:PR

-

‘When she sees people [men and women], she’s pleased,

-

she’s kind to them [her belly flows for them].’

(The glossing abbreviations used in this paper are: ACC = accusative case, BEN = benefactive, DEM = demonstrative pronoun, F = feminine, FUT = future tense, GEN = genitive, IMP = imperative, IPFV = imperfective, LOC = locative case, LP = local particle, M = masculine, MID = middle voice, N = neuter, NEG = negation, NOM = nominative case, OBL = oblique case, PASS = passive, PL = plural, PR = present tense, PRF = perfect, R = realis mode, REDUP = reduplication, SG = singular.)

The universal presence of metaphor in modern languages supports a deep view of the history of metaphor.

Metaphor and Ancient Texts

If the facility for metaphor was a recent innovation, then we should see no use of it in ancient texts. However this is not the case. Metaphors occur in Sanskrit, becoming a launching pad for grammatical change (Reinöhl, 2016). Going back even earlier, we find metaphors in early Sumerian. Approximately 3000 BC, the author of one of the oldest Sumerian texts, the Instructions of Shuruppak describes what happens if you speak improperly. He says ‘it (speaking improperly) will lay a trap for you’. ‘Speaking improperly’ cannot literally lay a trap, it is an action, not a person. This semantic conflict indicates that this is an instance of metaphor.

-

(2) u3 nu-jar-ra na-ab-be2-/e\ ejer-bi-ce3 jic-par3-gin7 ci-me-ci-ib2-la2-e

-

‘You should not speak improperly; later it will lay a trap for you.’ (Black, 2006:p. 275)

-

The presence of metaphor in the earliest writings, even as far back as the 5th millennium before the present, shows its temporal depth in modern human languages. This renders it more likely that the facility for metaphor arose earlier, during the protolanguage period.

Metaphor and Child Language

Another potential argument against the presence of metaphor in protolanguage could be made if metaphor did not occur in child language use. If children, for example, only acquired metaphors after acquiring literacy, this would point to a more modern cultural basis for metaphor use, making it unlikely to have arisen during protolanguage. However, recent research suggests that children as young as 3 years old — or even children “at the earliest testable ages” (Pouscoulous & Tomasello, 2020: p. 164) — understand age-appropriate metaphors (see also Pouscoulous, 2011).

So we have a number of arguments for the use of metaphor early in the history of human language. One of the prerequisites — combinatorial and, in fact, compositional, semantics — is met even in animal communication to a limited extent. A second prerequisite, one that motivates metaphorical use, is sufficient vocabulary. Combining lexical items, even in the face of clashing selectional restrictions, greatly improves the utility of enlarged vocabularies.

We have seen that metaphor is universally present in modern languages. It occurs in the earliest recorded texts that we have. It is found in the language of children before they have begun formal instruction, showing that it does not seem to be either an effect of written culture, nor a hard-to-learn behaviour. All of this evidence supports the view that metaphor has always been a consistent component of modern human languages, and so arose before them. This suggests, then, that metaphor began in the evolutionary period we call protolanguage.

We now turn to some of the structural implications for protolanguage that result from the presence of metaphor.

Obligatoriness in Metaphor

The ability to combine semantically clashing terms greatly expands expressivity, and so plausibly engenders an increase in conceptual productivity. This semantic development also has important effects on language structure.

Metaphorical interpretations, in functor–argument metaphors, only become available to a listener when the clashing argument in question is expressed overtly. The evidence suggests that this holds universally across languages and part-of-speech combinations (Reinöhl & Ellison, under review). Compare the following English examples from the British National Corpus:

-

(3)

-

If there is trouble it seems Jones is inevitably in the middle of it. (BNC, CEP)

-

(4)

-

What makes a car a classic? Must it follow fashion or be above it? (BNC, CFT)

-

(5)

-

You are usually given problems in advance, and will be asked to give your solutions and how you arrived at them. (BNC, EX5)

What we never find are zero arguments forcing metaphorical interpretations. In other words, e.g., the sentence You are usually given problems in advance, and will be asked to give your solutions and how you arrived does not occur. Where an argument like solutions clashes semantically with a functor’s selectional restrictions, we always see overt resumption: arrived at them.

The reason for obligatory argument expression is the asymmetry between a term’s default or ‘literal’ meaning — which comes to mind when the term is used in isolation — and readings that only emerge through semantic coercion. This coercion, in turn, only arises through the overt expression of the clashing, coercing argument (e.g., of solutions, forcing an interpretation of arrive as non-spatial). Strikingly, this phenomenon is immune to activation levels. Even in examples like (5), where solutions is the last word of the immediately prior (sub-)clause, it still has to be pronominally resumed. This immunity makes the phenomenon of metaphor-driven obligatoriness a striking new find, since argument expression is otherwise believed to be principally governed by information structure (specifically, activation levels), not semantic structure.

The evidence for metaphor-driven argument obligatoriness as a universal of human language is overwhelming and diverse. In an earlier study (Reinöhl & Ellison, under review) we conducted large-scale corpus searches of English (British National Corpus) as well as of a fieldwork corpus of Vera’a, an indigeneous Austronesian language of Vanuatu (Schnell, 2011). This research complemented prior research (Reinöhl, 2016) which also found no counter-examples in a historical corpus of Indo-Aryan languages. We also conducted a psycho-linguistic sentence-completion experiment with 248 native speakers of English responding to a total of approximately 1500 sentence-completion questions. In the stimuli, a first sentence primed either a non-clashing or a clashing argument which could then be resumed by zero or by a pronoun in the next sentence. More than 99% of the responses provided pronominal resumption for clashing arguments. For non-clashing arguments, less than 50% of the responses provided pronominal resumption. Together, these results offer “very strong evidence” (Kass & Raftery, 1995) in Bayesian terms for metaphorical combinations requiring argument overtness (details and graphs can be found in Reinöhl & Ellison, under review).

Two examples from the 13 stimuli used in the experiment are shown in (6)–(7) below. The participants are shown two sentences, the first of which primes a literal or clashing argument (e.g., box of sweets, something weird) to a functor in the second sentence. Different realisations of that argument are presented in a drop-down menu, including zero and pronominal realisation (the latter in all naturally occurring options). Participants are then asked to choose the most natural sentence completion. The instruction is: ““Please read the text carefully, consider all the options, and then pick the one that sounds best and/or makes the most sense to you. Remember: there are no right answers, we just want to know what phrasing works best for you.”

A sentence-completion experiment yields more relevant results if stimuli are as natural as possible. Natural-language collocations vary, and so person and number features of referents also vary in some of our stimuli. For example, it is more pragmatically natural to make predictions about a second person that “You will find some chocolates …” rather than to make such a prediction in the first person. Person and number have no effect, however, on whether or not a pronominal argument is supplied in our experiment.

-

(6)

-

Here is a box of sweets. You will find some chocolates at

-

the bottom.

-

the bottom of it.

-

its bottom.

-

(7)

-

Something weird is going on there. I just can’t get to

-

the bottom.

-

the bottom of it.

-

its bottom.

The results are clear: Whereas literal-argument stimuli such as (6) show mixed responses with and without pronominal arguments, metaphorical-argument stimuli such as (7) show pronominal-argument responses 99% of the time. This sentence-completion experiment thus reinforces the findings from the natural corpus studies: Metaphor-driving arguments are obligatorily overt.

The obligatoriness of metaphor-driving arguments is not just a striking feature of contemporary modern languages. We believe that it also played a key role in the evolution of grammar.

Metaphor as the Launching Pad for Syntax

Language evolution is characterized by continuity in some domains and discontinuity in others. On purely logical grounds, metaphors arising from a semantic clash between default senses were available at the dawn of contemporary human language. In this regard, we find continuity. On the other hand, it is plausible that the need for expanding expressivity through metaphor increased over time, along with a change in social and cultural structures. Because of the obligatoriness associated with arguments in functor–argument metaphors, more of these means more cases of overt arguments regardless of activation levels. In the following sections, we outline some of the effects of such a development.

Word Order

Firstly, metaphor likely played a crucial role in the development of conventionalised word order (Reinöhl, 2016). Every language seems to have a default word order. This includes “free word order” languages (e.g., from Australia), which are (mostly) syntactically free, but still structured by principles such as “topic first” or “more-newsworthy first” (e.g., Austin, 2001; Mithun, 1987; Reinöhl, 2020). How did such conventionalization come about? Logically, conventionalized word order would only have developed when enough material was overtly expressed, and this overt expression happened frequently enough. If most utterances are isolated words, a conventionalized word order is not so important. Natural discourse can very well do without much overt expression: since the same participants tend to be tracked through a stretch of discourse, they can be economically expressed with zero anaphors (e.g., Du Bois, 1987). Only the use of metaphor forces argument overtness, even under conditions of maximum activation. The socio-culturally conditioned increase in the prevalence of metaphor — to the point of pervading everyday discourse as has been impressively demonstrated (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980 and others) — meant more and more overt arguments. Due to language contact and L2 learners preferring analytical structures, argument obligatoriness may even become generalized as a syntactic rule, as in much of English syntax. With enough material expressed overtly often enough, the stage is set for conventionalization. The drive for economy in mental effort promotes routinization of a default word-order in order to reduce speaker effort. (A later section describes how conventional word order may develop further into fixed word order as a side effect of grammaticalization.)

Demonstratives

We believe that metaphor not only played a key role in the development of word order defaults, but may have been the prime contributing factor in demonstrative pronouns reaching the functional range they show in modern languages.

Demonstratives are one part of speech that very probably existed in protolanguage. On the one hand, they are one of the few candidates — if not the only one — for a universal part of speech in modern languages (Evans & Levinson, 2009). On the other hand, they are also a prime candidate for evolutionarily early language use — in particular, the situative use of verbally pointing to a physically present referent. This use has been likened to pointing gestures, which have attracted intense attention in language evolution research including in primate communication research (see Tomasello & Call, 2019 for an overview). In addition to these points, demonstratives are acquired early (Diessel, 2006). This makes them particularly good candidates for an early role in protolanguage.

The use of pronouns in resuming semantically clashing arguments is not situative, however, but anaphoric. When are pronouns used anaphorically in modern languages even when the participant is highly activated? They are used if the language does not allow zero arguments (as is typical in the grammar of English, a typological outlier in this respect), when there are several competing referents, and for semantically clashing arguments. The only hard and universal condition among these three, which holds regardless of grammatical and discourse specifics, is the last one — anaphoric resumption of a semantically clashing argument. We therefore propose that what is often considered the prime function of demonstratives — anaphoric use — arose as another direct consequence of metaphor.

Metaphor-driven argument overtness shaped human language in at least two key respects, both of which are considered universal hallmarks of modern languages: conventionalized word order and anaphorically used demonstratives. We now show how grammaticalization takes these developments further: from conventionalized to fixed word order and from metaphor-driven to syntactically-required argument overtness.

Obligatoriness and Grammaticalization

Smith (2008: p. 13) diagnoses that language evolution modelling tends to stop at the “words and rules” stages and fails to provide an account of continuing language evolution in the form of grammaticalization (but, e.g., Smith, 2011). We here respond to this challenge by proposing a mechanism for how early compositionality seamlessly fosters grammaticalization. An earlier study (Reinöhl, 2016) explores the grammaticalization of postpositions and — as a by-product — of postpositional phrases over the 3000 years of attested Indo-Aryan history. Sanskrit has “free”, i.e., conventionalised but not fixed word order, and lacks strongly grammaticalized function words. Modern Indo-Aryan languages have fixed word order in postpositional phrases, which are headed by strongly grammaticalized postpositions. Compare the following examples:

-

(8) GEN madhye

-

nimaṅkṣye 'haṃ salilasya madhye

-

plunge.FUT.MID.SG 1SG water.GEN.SG.N middle.LOC.SG.N

-

‘I will plunge into the middle of the water.’ (AiB 8.21, see Reinöhl, 2016: 91)

-

(9) madhye … GEN

-

Madhye vā idam ātmano ‘nnaṃ

-

middle.LOC.SG.N or DEM.NOM.SG.N body.GEN.SG.M food.NOM.SG.N

-

dhīyat

-

put.PASS.3SG

-

‘In the middle of the body, food is put’ (ŚāṅB 15.3, see Reinöhl, 2016: 127)

-

(10) zero

-

ná enam ūrdhváṃ ná tiryáñcaṃ ná mádhye pári

-

NEG DEM.ACC.SG.M above NEG below NEG middle.LOC.SG.N LP

-

jagrabhat

-

comprehend.PRF.3SG

-

‘(No one) comprehended him above, below, or in the middle.’ (YV 32.2, see Reinöhl, 2016: 88)

-

(11) semantically clashing

-

iṣṭásya mádhye áditir ní dhātu naḥ

-

wish.GEN.SG.N middle.LOC.SG.N Aditi.NOM.SG.F down put.IMP.SG ACC.PL

-

‘Aditi should place us in the middle of (our) wish.’ (RV 10.11.2, see Reinöhl, 2016: 149)

-

(12) Hindi

-

maĩ śahar mẽ rahtī hū̃

-

1SG city.OBL.SG in live.IPFV.SG.F be.SG

-

‘I live in the city’ (see Reinöhl, 2016: 164)

The Sanskrit spatial noun madhye (middle.LOC.SG.N) ‘in the middle’ developed into the Hindi postposition mẽ ‘in’ (e.g., Kahr, 1975, 1976, Svorou, 1988, Rubba, 1994 for research on the grammaticalization of adpositions across languages). In Sanskrit, the normal order of madhye and its argument is GEN(itive-marked noun) madhye (8). However, order was only conventionalized, not syntactically fixed (9), even allowing for discontinuity (Reinöhl, 2016: pp. 122–131). When non-clashing and activated, the argument could remain zero (10). Semantically clashing default senses required argument overtness (11). This is the scenario described in the above section “Obligatoriness in metaphor”, with conventionalized, but non-rigid word order, zero expression for activated but non-clashing arguments, and pronominal resumption for activated but clashing arguments. In Hindi and other New Indo-Aryan languages, word order is rigid and the argument must be overt, whether or not it clashes semantically (12). Historical evidence reveals that this change ‘in the middle (of x)’ to ‘in x’ took place through routinization of the exact string GEN madhye (with the genitive later developing into the syncretized “oblique” case form). Other permutations of word order, or examples with a zero argument, do not show the new meaning ‘in X’ (Reinöhl, 2016: pp. 166–167 for the relevant evidence from Early New Indo-Aryan).

So we see two stages of historical development. First, metaphor universally leads to the conventionalisation of word order and to the anaphoric use of demonstratives in cases of resumption. Second, grammaticalization leads, via routinization, to the fixation of word order and to obligatory arguments. The presence of functor–argument metaphors entails the first stage. While it enables the second stage, it does not guarantee it. Grammaticalization has attracted much attention, but it is actually a rare process in the overall landscape of language change. Metaphor use is highly productive and frequent, but most languages only have a handful of function words. Thus, while grammaticalization is found in every language, it is rare in the sense that only a few elements and constructions ever undergo this process. Furthermore, not all function words develop from metaphorically-triggered grammaticalization; metonymy-triggered grammaticalization is another important pathway (e.g., Bybee et al., 1994). Thus, grammaticalization should not be seen as a distinguishing feature of language as opposed to protolanguage. Metaphor does not force grammaticalization, but renders it possible if other circumstances facilitate it.

Metaphor and the holistic vs analytic debate

A major debate in language evolution research has revolved around whether language developed from a holistic (holophrastic) or analytic (compositional) starting point. The study of metaphor allows for a deeper understanding of the contributions of both holistic and analytic strategies in encoding meaning.

In a nutshell, the holistic account assumes that early signals were semantically complex without internal form–function segmentation. A sign might have meant, for example, ‘Careful, there is a predator at ground level!’ without separate sub-components meaning ‘careful’, ‘predator’ or ‘at ground level’. Only over time did a form–function segmentation evolve (e.g., Arbib, 2005; Wray, 1998). The analytic account, by contrast, holds that language started off with words having more or less individualised meanings, which at first were used in isolation and later in ever more complex combinations. Thus, ‘predator!’ would initially be uttered on its own, but later combined with, for example, ‘at ground level’ or ‘beware!’ (e.g., Bickerton, 1990, 2009; Tallerman, 2007). Of course, if ‘predator’ is uttered on its own as a warning, in that context at least, its meaning must incorporate the intentions behind the speech act of uttering the word, e.g., those of warning someone that a predator is nearby. It seems difficult to separate holistic terms and analytic terms used holistically in this way.

The holistic vs analytic debate is often cast as an either/or, but the study of metaphor reveals that there must have been both holistic and analytic encoding strategies active already at the dawn of human language. The issue in the literature is that the holistic and analytic approaches are typically cast as denotation-only views of word meaning. However, word meanings do not only consist of denotations, but also of selectional restrictions.

... the proper way to understand the meaning of words is in terms of their denotations and the restrictions that other words impose on them. And it is the latter that govern how words interact semantically. ... Meeting a selectional restriction is a matter of justifying a lexical presupposition, the presupposition that a term has a certain type. This analysis yields a theory of lexical meaning: to specify the type and the denotation of a word is to give its lexical meaning. (Asher, 2011: ix)

For example, to arrive denotationally refers to an event, a movement in space, but it also involves selectional restrictions for someone or something able to move, as well as for a target. In this sense, then, a functor’s semantic structure is always partially holistic, as it combines denotational with selectional meaning components. The full semantic specification, however, depends on other material — arguments. These are provided through a combinatorial, analytic strategy.

If the arguments to a functor can be filled by highly primed entities in the pragmatic context, and so left implicit, then the functor is functionally holistic. For example, a hypothetical argumentless arrive on its own would refer to a salient person (e.g., someone visible) arriving somewhere (e.g., here). But when metaphoric uses are intended, explicit arguments need to be supplied, and so multiword utterances are not only possible, but necessary. This was the launching pad for more structured and frequent multiword constructions.

In this paper, we do not speculate about the emergence of the very first terms of protolanguage, in contrast to the focus of the holism vs analyticity debate. But we contend that — as soon as some terms and term combinability became available, then metaphor became a possibility along with it. This is because even terms with relatively “individualised” meanings are never just that (i.e., analytic), but always partially holistic through their selectional restrictions. Once metaphor is present and clashing term combinations occur, the fundamental organizational effects on syntax commence, over time turning protolanguage into fully-fledged language.

Conclusions

We have argued in this paper for a central — and hitherto overlooked — role of metaphor in language evolution. Functor–argument metaphor arises from the semantic clash between terms’ default meanings. Such clashes can only occur if terms can be combined and the combinations interpreted compositionally. Once this can be done for naturally compatible terms, clashing terms can also be combined to make metaphors, transcending compositionality. The rise of metaphor significantly expanded expressivity. It also drove the development of modern language syntax. The need for overt metaphor-driving arguments led to word order conventionalization and to the rise of modern demonstrative pronouns. This development continued and continues as a by-product of grammaticalization, turning default word order into fixed word order, and semantically-triggered into syntactically-required argument overtness. Metaphor, we argue, is what took us from protolanguage to the elaborate grammatical structures of fully-fledged human languages.

References

Arbib, M. A. (2005). From monkey-like action recognition to human language: An evolutionary framework for neurolinguistics. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28(2), 105–124.

Asher, N. (2011). Lexical meaning in context: A web of words. Cambridge University Press.

Austin, P. (2001). Word order in a free word order language: The case of Jiwarli. In J. Simpson, D. Nash, M. Laughren, P. Austin, & B. Alpher (Eds.), Forty years on: Ken Hale and Australian languages (pp. 205–223). Pacific Linguistics.

Bickerton, D. (1990). Language & species. University of Chicago Press.

Bickerton, D. (2009). Adam’s tongue: How humans made language, how language made humans. Hill and Wang.

Billow, R. (1975). A cognitive–developmental study of metaphor comprehension. Developmental Psychology, 11, 415–423.

Black, J. A. (2006). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press.

Bowdle, B. F., & Gentner, D. (2005). The career of metaphor. Psychological Review, 112(1), 193–216.

Bybee, J., Perkins, R., & Pagliuca, W. (1994). The evolution of grammar. Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press.

Chater, N., & Christiansen, M. H. (2010). Language evolution as cultural evolution: How language is shaped by the brain. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1(5), 623–628.

Dahl, C. D., & Adachi, I. (2013). Conceptual metaphorical mapping in chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). eLife, 2013(2), e00932.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

Dennett, D. (1995). Darwin’s dangerous idea: Evolution and the meanings of life. Penguin/Simon & Schuster.

Diessel, H. (2006). Demonstratives, joint attention and the emergence of grammar. Cognitive Linguistics, 17(4), 463–489.

Du Bois, J. W. (1987). The discourse basis of ergativity. Language, 64, 805–855.

Evans, N., & Levinson, S. (2009). The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32, 429–448.

Evans, N., & Wilkins, D. (2000). In the mind’s ear: The semantic extensions of perception verbs in Australian languages. Language, 76, 546–592.

Graesser, A., Long, D., & Mio, J. (1989). What are the cognitive and conceptual components of humorous texts? Poetics, 18, 143–164.

Kahr, J. C. (1975). Adpositions and locationals: Typology and diachronic development (Vol. 19, pp. 21–54). Working Papers on Language Universals.

Kahr, J. C. (1976). The renewal of case morphology: Sources and constraints (Vol. 20, pp. 107–151). Working Papers on Language Universals.

Kass, R. E., & Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 773–795.

Katz, A. (2017). Psycholinguistic approaches to metaphor acquisition and use. In E. Semino & Z. Demjén (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of metaphor and language (pp. 472–485). Routledge.

Kovecses, Z. (1988). The language of love. Bucknell University.

Kuteva, T., Heine, B., Hong, B., Long, H., Narrog, H., & Rhee, S. (2019). World lexicon of grammaticalization (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Mithun, M. (1987). Is basic word order universal? In R. Tomlin (Ed.), Coherence and grounding in discourse (pp. 281–328). John Benjamins.

Patterson, N., Richter, D. J., Gnerre, S., Lander, E. S., & Reich, D. (2006). Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees. Nature, 441, 1103–1108.

Pollio, H. R., Barlow, J. M., Fine, H. J., & Pollio, M. R. (1977). Psychology and the poetics of growth: Figurative language in psychology, psychotherapy, and education. Erlbaum.

Ponsonnet, M. (2014). Figurative and non-figurative use of body-part words in descriptions of emotions in Dalabon (northern Australia). International Journal of Language and Culture, 1(1), 98–130.

Pouscoulous, N. (2011). Metaphor: For adults only? Belgian Journal of Linguistics, 25(1), 51–79.

Pouscoulous, N., & Tomasello, M. (2020). Early birds: Metaphor understanding in 3-year-olds. Journal of Pragmatics, 156, 160–167.

Quinn, N. (1987). Convergent evidence for a cultural model of American marriage. In D. Holland & N. Quinn (Eds.), Cultural models in language and thought (pp. 1–40). Cambridge University Press.

Reinöhl, U. & Ellison, T. M. (Under review). Metaphor forces argument overtness.

Reinöhl, U. (2016). Grammaticalization and the rise of configurationality in indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press.

Reinöhl, U. (2020). Continuous and discontinuous nominal expressions in flexible (or “free”) word order languages. Patterns and correlates. Linguistic Typology, 24, 71–111.

Rubba, J. (1994). Grammaticization as semantic change. A case study of preposition development. In W. Pagliuca (Ed.), Perspectives on grammaticalization (pp. 81–101). Benjamins.

Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S., Murphy, J., Sevcik, R. A., Brakke, K. E., Williams, S. L., Rumbaugh, D. M., & Bates, E. (1993). Language comprehension in ape and child. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(3-4), 1–222.

Schnell, S. (2011). A grammar of Vera’a, an oceanic language of North Vanuatu. Department of General Linguistics, Kiel University (n.d.). (online at: https://www.academia.edu/2317752/Schnell_2011_A_grammar_of_Veraa_an_Oceanic_language_of_North_Vanuatu)

Smith, A. D. M. (2011). Grammaticalization and language evolution. In B. Heine & H. Narrog (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of grammaticalization (pp. 142–152). Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. D. M. & Höfler, S.H. 2015. The pivotal role of metaphor in the evolution of human language. In J. E. Dı́az Vera (ed.), Metaphor and metonymy across time and cultures (pp. 123–139). : Mouton de Gruyter.

Smith, A. D. M., & Höfler, S. H. (2017). From metaphor to symbols and grammar: The cumulative cultural evolution of language. In C. Power et al (Eds.), Human origins and social anthropology (pp. 153–179). Berghahn.

Smith, K. (2008). Is a holistic protolanguage a plausible precursor to language? A test case for a modern evolutionary linguistics. Interaction Studies, 9(1), 1–17.

Suzuki, T. N., Wheatcroft, D., & Griesser, M. (2017). Wild birds use an ordering rule to decode novel call sequences. Current Biology, 27(15), 2331–2336.e3.

Svorou, S. (1988). The experiential basis of the grammar of space. Evidence from the languages of the world. SUNY dissertation.

Sweetser, E. (1990). From etymology to pragmatics: Metaphorical and cultural aspects of semantic structure. Cambridge University Press.

Tallerman, M. (2007). Did our ancestors speak a holistic protolanguage? Lingua, 117, 579–604.

Tomasello, M., & Call, J. (2019). Thirty years of great ape gestures. Animal Cognition, 22(4), 461–469.

Wray, A. (1998). Protolanguage as a holistic system for social interaction. Language and Communication, 18, 47–67.

Zuberbühler, K. (2002). A syntactic rule in forest monkey communication. Animal Behaviour, 63(2), 293–299.

Zuberbühler, K. (2018). Combinatorial capacities in primates. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 21, 161–169.

Acknowledgements

Authorship is shared equally. We are grateful for questions and comments from the audience at Protolang 6 at Lisbon, as well as from two anonymous reviewers. We gratefully acknowledge funding by the German Science Foundation (CRC 1252, Cologne; Emmy Noether Programme, University of Freiburg).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Note and Data Availability

This paper refers exclusively to data either published or to be published elsewhere.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Joanna M. Setchell

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ellison, T.M., Reinöhl, U. Compositionality, Metaphor, and the Evolution of Language. Int J Primatol 45, 703–719 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-022-00315-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-022-00315-w