Abstract

In contrast to pelagic and benthic realms of the aquatic ecosystems, studies on the metaphytic habitats remain underrepresented in the literature. However, this realm may have a potential impact on composition and diversity of the open water assemblages through metacommunity processes (source-sink dynamics, mass-effect) especially in small ponds with extended littoral zone. Using a limnocorral experiment we studied how metaphyton affects diversity and composition of open water phytoplankton in a small eutrophic pond in the vegetation period. The three habitats (metaphyton, isolated and non-isolated open water) showed considerable differences in their taxa and functional group composition. Abundance-based diversity measures did not reveal remarkable differences among the assemblages of the three habitats. However, taxonomic and functional richness of the metaphyton and the non-isolated part of the pelagial significantly exceeded that of the limnocorral. Incidence-based similarity index values also showed closer resemblance of the metaphyton and plankton samples compared to that of the limnocorral. In the case of several functional groups, their functional redundancy in the metaphyton exceeded that in the open water areas. These results suggest that the metaphyton provides a refuge for several euplanktic elements that survive in the littoral and occasionally enrich the phytoplankton of the open water areas, representing that a within–lake metacommunity processes shape the composition and functioning of the open water areas in standing waters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the rules of community assembly has long been of interest to researchers and inspired a number of studies on this subject (Hille Ris Lambers et al., 2012; Letten et al., 2017; Ellner et al., 2022). To reconcile the discrepancies among the various theories, Vellend (2010, 2016) proposed a framework that focuses on four basic processes of community assembly, namely: speciation, demographic stochasticity, selection and dispersal. Although, evolutionary processes can occur in a short period of time, especially in the case of microbes (Fussmann et al., 2003), speciation as community assembly rule might be important in phytoplankton communities only at large geographic scales. In contrast, demographic stochasticity is more important in the case of small populations at smaller spatial scales. According to the Baas-Becking view of microbial realm (Baas-Becking, 1934), environment selects the organisms best adapted to the conditions provided by the habitats; otherwise, everything could be found everywhere. Yet, according to several studies, assembly of local communities are primarily driven not only by niche processes but dispersal too (Borics et al., 2021). The relative importance of these processes mostly depends on the size and type of the observed water bodies (Várbíró et al., 2017). Leibold & Chase (2018) determined four basic paradigms of metacommunity assembly (patch-dynamics, species-sorting, mass- effect, neutral view) built around the concept of selection and dispersal, of which mass-effect (source-sink dynamics) has the greatest impact on phytoplankton assemblages. This paradigm states that propagule pressure from an abundant source population can maintain high diversity in the recipient habitat, even if it provides unfavourable conditions for the newcomers (Mouquet & Loreau, 2003). Several studies highlighted the importance of this process in maintaining diversity across isolated habitats like lakes (Szabó et al., 2019) or in river–lake complexes (Bergström et al., 2008; Bortolini et al., 2017), but it has relevance also in within-lake dynamics of microorganisms (Rimet et al., 2023).

Aquatic habitats in general can be divided into pelagic and benthic realms, inhabited by free-floating and sessile creatures respectively. However, besides these two realms a third one, the metaphyton can also be distinguished. The term was used first by Behre (1956) who defined metaphyton as algae, which are associated with macrophytes but not attached to them. Later definitions: “group of algae found aggregated in the littoral zone, which is neither strictly attached to substrata nor truly suspended” (Hutchinson, 1975), or „loose collection of nonmotile or slightly motile algae without any obvious mode of attachment” (Round, 1981) are identical in the sense, that besides filamentous forms, flagellates and other components of the microflora (diatoms and desmids) have been also included. In recent publications the meaning of the term was restricted to unattached filamentous green algae (Howell et al., 1990; Kelly et al., 1995; Pikosz & Messyasz, 2015). These different definitions beside leading to terminological confusion, neglect an assemblage that has the potential to significantly contribute to the diversity and functioning of the littoral.

Metaphyton frequently develops in wetlands, or in sheltered areas of lakes’ littoral zone, and is associated with good light conditions and warm waters (Goldsborough & Robinson, 1996). Parts of aquatic macrophytes below the water table together with the filamentous algae create a three-dimensional matrix, which impedes water movements and create lentic conditions that allow the development of various environmental gradients (Barko & Smart, 1986; Dvořák & Liskova, 1970; Alahuhta et al., 2013). Littoral vegetation reduces the gas exchange with the air and diffusion of oxygen to the sediment (Moore et al., 1994), furthermore nutrient uptake and release by the plants (Lu et al., 2018), and production of allelopathic substances (Gross, 2003) also contribute to the microheterogeneity of this environment. Heterogeneity of the littoral creates large habitat diversity allowing the coexistence of several metaphytic algal species (Borics et al., 2003). The metaphyton is not just a unique assemblage, but might serve as a refuge for many species and depending on hydrological conditions may inoculate the pelagic realm, contributing and maintaining its high diversity (Görgényi et al., 2019; Naselli-Flores & Barone, 2012). The findings of Görgényi et al. (2019) suggest that metaphyton plays also pivotal role in the recruitment of phytoplankton in lakes with extended littoral zone, because metaphytic components of the phytoplankton do not show asymptotes during spatially and temporally intensive samplings. This finding implies that the contribution of metaphyton to the phytoplankton assemblage can be considered as mass-effect, which assumes that because of the propagule pressure (or source-sink dynamics) from the metaphyton, diversity of phytoplankton can be high even under unfavourable conditions (Leibold & Chase, 2018). In accordance with the above-mentioned arguments, we assumed that in eutrophic lakes a source-sink dynamic operates between the metaphyton and the pelagic phytoplankton, and thus within-lake metacommunity processes shape the phytoplankton diversity in these systems.

To test this assumption a study question was raised: how does the diversity and composition of the open water phytoplankton change with the exclusion of the source-sink dynamics in a macrophyte dominated standing water. While field studies provide sufficient information on the source-sink dynamics in natural conditions, its real impact can be studied exclusively in controlled environment. Therefore, we studied this question in a whole pond experiment, where a part of the pelagic region of a small eutrophic pond was isolated by limnocorral, and tested how the metaphytic algal assemblages differ from the isolated and non-isolated phytoplankton.

We had the following hypotheses:

-

(i)

The taxonomic and functional composition (functional groups (FGs)—Reynolds et al., 2002) of the metaphyton will be different from the two phytoplankton assemblages, showing greater similarity between the metaphyton and the non-isolated phytoplankton, than between metaphyton and isolated phytoplankton.

-

(ii)

The diversity of the metaphytic assemblage will be higher than that of the phytoplankton assemblages in terms of both taxa and functional groups.

-

(iii)

The metaphyton has a more stable community structure than phytoplankton, therefore comparing to the other two habitats, less changes are expected in its composition during the vegetation period.

Materials and methods

Study site

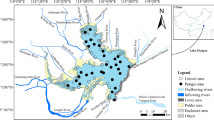

The studied pond is located in the Tuzson János Botanical Garden, in Nyíregyháza, Hungary (WGS84: 21.710588; 47.973473—Fig. 1), which is a small eutrophic pond (Supplementary Table 1) with large amount of macrophytes [roughly 60% cover, dominated by Nymphaea alba L. and Ceratophyllum demersum L.]. The maximum depth of the pond is 2.2 m. The middle part of the open water area was isolated by plastic foil (limnocorral) in a cylindrical shape from the bottom to the surface. The limnocorral was installed at the 20th of March to have enough time for the development of differences between the communities in the different habitats. The bottom of the limnocorral was stabilized with concrete weights, and all seedlings of macrophytes were removed from the bottom of the isolated part. Area of the pond is approximately 600 m2 of which 10 m2 was isolated.

Sample collection, microscopic analysis and data processing

Metaphyton and phytoplankton samples were collected weekly from 13th of June to 10th of October in 2019. Altogether 51 samples were collected from 3 points (Figs. 1 and 2) during 17 weeks. Phytoplankton samples were taken by a tube sampler from the euphotic zone (2.5 × depth of Secchi-disc) or from the whole water column from both the isolated (L) and non-isolated (P) part of the pond. Metaphyton (M) samples were collected with a plastic dish from the water among the macrophyte stands 10–20 cm below the surface. Water samples for abiotic variables (temperature, oxygen concentration, oxygen saturation, pH, conductivity, total nitrogen, total phosphorus) were collected at monthly intervals (Supplementary Table 1).

Samples were preserved with Lugol’s solution in the field (CEN 13946, 2003). Counting of algal units (cells, colonies, or filaments) were performed according to the CEN 15204 (2006) standard using an inverted microscope (Leica DMIL) at ×100 and ×400 magnification. Estimating the biomass, the linear dimensions of 20 specimens of each taxon were measured and for calculating the phytoplankton biovolume realistic 3D models were used following Borics et al. (2021). Based on the AlgaeBase (Guiry & Guiry, 2023) the currently accepted names of phytoplankton species were used.

Functional approaches in biodiversity studies provide extensive options to examine communities considering community assembly and ecosystem functioning (Mason et al., 2005; Abonyi et al., 2018). Since there are well established functional groups for phytoplankton in use by many algologists, identified taxa were classified into Reynolds’ functional groups (FGs) (Reynolds et al., 2002; Borics et al., 2007; Padisák et al., 2009).

For richness metrics number of taxa and number of FGs were used. Richness metrics are easily interpretable indices of diversity and they are easy to use, however they do not consider relative abundance. Besides the richness metrics, Shannon diversity index (Shannon, 1948) was applied, which is a broadly used diversity metric that takes into account relative species and group abundances. Furthermore, Pielou’s evenness (Pielou, 1966) and Berger–Parker diversity (Berger & Parker, 1970) were also used to express the dominance relations in the communities. To test the similarity of the three habitats Jaccard similarity index was applied (Jaccard, 1901). Furthermore, to test dissimilarity of changes within the sampling points, community change rate was calculated using Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (Bray & Curtis, 1957) values and 1-Jaccard similarity index (incidence based community change rate) values between consecutive samples in each habitat.

Statistical analyses

To visualize the differences of taxa and functional group composition between the sampling points (M, P, L) relative biomass data of taxa and FGs were applied using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). To test the statistical difference in the composition of the three habitats, analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) and permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) were performed. To address pairwise comparisons between the habitats, pairwise.adonis function was used in R (R Core Team, 2022).

To test the similarity between the taxonomic and functional composition of the habitats, Jaccard similarity index was calculated for each sampling time between the habitat pairs (M–P, L–M, L–P) (PAST software, version 4.10; Hammer et al., 2001). For the calculation of community change rate values based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and 1-Jaccard similarity, PAST software was used (version 4.10; Hammer et al., 2001).

Taxa and functional group richness, Shannon diversity, Pielou’s evenness and Berger–Parker diversity were also calculated by the PAST software (version 4.10; Hammer et al., 2001).

Statistical differences of community change rate, taxa and functional group richness, Shannon diversity, Pielou’s evenness, Berger–Parker diversity and Jaccard similarity were tested with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests (in the case of normally distributed data). Kruskal–Wallis test was used with pairwise Wilcoxon test as a post-hoc pairwise comparison (in the case of non-normally distributed data). Analyses (NMDS, ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test, Tukey and pairwise Wilcoxon tests) were performed in R statistical environment (R Core Team, 2022).

To compare the functional redundancy in FGs between the habitats species saturation curves were fitted for each FGs using iNEXT R package (Hsieh et al., 2016).

Results

Number of taxa and functional groups in the three habitats

Altogether 225 taxa were found in the 51 samples, from which 177 occurred in the metaphytic habitat (M), 172 in the non-isolated phytoplankton (P) and 152 in the isolated phytoplankton (L) (Supplementary Table 2). Number of shared taxa between the habitats was 118 and number of unique taxa were 28, 17 and 20 for M, P and L respectively (see Supplementary Table 2).

The observed taxa belonged to 27 FGs, from which 24 FGs were present in the M, 25 FGs in P and 21 FGs in L (Table 1). Only 7 FGs were present in all samples. Unique FGs were only found in M (FG: G and TIC) and in P (FG: A) (see Table 1).

Taxa and functional group composition of the habitats

Distribution of the samples of the three habitats showed an overlap in the NMDS plot (Figs. 3 and 4). While we observed a considerable scatter regarding the metaphyton (M) and the limnocorral (L) samples, an overlap could also be observed between them. The non-isolated plankton samples (P) showed overlap with both M and L, and these samples were more concentrated.

Despite the overlaps, the results of the ANOSIM showed significant differences among the composition of the three habitats for both taxa (R = 0.2012 and P = 0.0001) (Fig. 3; Table 2) and FGs (R = 0.1382 and P = 0.0001) (Fig. 4; Table 2). However, the R-values fell between 0.1 and 0.25 in both cases, indicating high similarity between the habitats.

Clusters found on the NMDS plot were also tested using PERMANOVA, which indicated significant compositional differences among the habitats (P < 0.0001) in the case of both taxa and FGs. The results of the pairwise comparisons (pairwise.adonis function) also showed significant differences between all habitat pairs (Table 2).

Similarity of habitats

The values of the Jaccard similarity index were the highest in the metaphyton and non-isolated phytoplankton relation (M–P) and the lowest in the metaphyton and isolated phytoplankton relation (L–M) in the case of both taxa and FGs (Fig. 5a, b). The ANOVA showed significant differences between the habitat pairs (P = 0.00004 for taxa and P = 0.0178 in the case of FGs; Table 3). The Tukey post hoc test showed the clear separation of the M–P pairs from the L–M pairs for both taxa and FGs (Table 3).

Functional redundancy in the different habitats

To study the differences in functional redundancy among the three habitats we created species saturation curves for each FG (Fig. 6). Functional groups with low redundancy (species numbers in the FG < 5; D, E, Y, K) showed no remarkable differences. In the case of most species rich groups (J, W1, TIB, F, Lo) functional redundancy was considerably higher in the metaphyton (M) and in the plankton of the non-isolated part of the pond (P) as compared to that in the limnocorral (L). An opposite tendency was found only for the X2 FG, where the functional redundancy of the limnocorral (L) and plankton (P) samples exceeded that of the metaphyton (Fig. 6k).

Temporal changes of diversity metrics in the three habitats

We also investigated how diversity metrics (species and FG richness, Shannon diversity, Pielou’s evenness and Berger–Parker diversity) vary in the three habitats. Nearly all metrics (except community change rate based on 1-Jaccard similarity) showed a decreasing trend in diversity (increase in Berger–Parker diversity) with fluctuations throughout the study period (Figs. 7a, e, g, i, k and 8a, e, g, i, k).

Line graphs: changes of taxa based community change rates and diversity metrics during the study period. Boxplots: differences in metric values among the habitats. The three colours indicate the three habitats. Bray–Curtis distances between consecutive samplings as community change rate in time (A) and between habitats (B). 1-Jaccard index values between consecutive samplings as community change rate in time (C) and between habitats (D). Number of taxa in time (E) and between habitats (F). Changes of Shannon diversity values in time (G) and between habitats (H). Pielou’s evenness values in time (I) and between habitats (J). Berger–Parker diversity in time (K) and between habitats (L). Abbreviations and colours: M metaphyton, green, P non-isolated phytoplankton, blue, L limnocorral (isolated phytoplankton), yellow

Line graphs: changes of FG based community change rates and diversity metrics during the study period. Boxplots: differences in metric values among the habitats. The three colours indicate the three habitats. Bray–Curtis distances between consecutive samplings as community change rate in time (A) and between habitats (B). 1-Jaccard index values between consecutive samplings as community change rate in time (C) and between habitats (D). Number of FGs in time (E) and between habitats (F). Changes of Shannon diversity values in time (G) and between habitats (H). Pielou’s evenness values in time (I) and between habitats (J). Berger–Parker diversity in time (K) and between habitats (L). Abbreviations and colours: M metaphyton, green, P non-isolated phytoplankton, blue, L limnocorral (isolated phytoplankton), yellow

Differences between diversity metrics in the three habitats

The mean values of the number of taxa and FGs were the highest in the metaphyton (M) and plankton (P) samples and the lowest in the limnocorral (L). The ANOVA showed significant differences in the case of both richness metrics (P = 0.0003 for the number of taxa; and P = 0.0219 for the number of FGs—Figs. 7f and 8f). The Tukey test highlighted that there were significant differences between L–P and L–M in the case of number of taxa, while in the case of number of FGs, significant difference appeared only in the L–M relation (Table 3).

We found the highest mean Shannon diversity values in the metaphyton samples (M) both for taxa (Fig. 7h) and FGs (Fig. 8h). The results of the ANOVA, however, did not indicate significant differences for taxon diversity (P = 0.1340; Table 3). In contrast, regarding FGs, it appeared to be significant (P = 0.0406; Table 3). Despite the result of the ANOVA for FGs, the Tukey test did not show significant differences between the habitats (Table 3), only marginal significance was observed between metaphyton and the other two habitats (P = 0.0746 for M–P and P = 0.0664 for M–L).

Even though mean values of Pielou’s evenness were the highest in the metaphyton (M) in the case of both taxa and FGs (Figs. 7j and 8j) there were no significant difference between habitats (Table 3).

Despite mean and median values of Berger–Parker diversity were the highest in the limnocorral (L) in the case of both taxa and FGs (Figs. 7l and 8l), no significant difference between the three habitats were observed (P = 0.133 for taxa (ANOVA); P = 0.2937 for FGs (Kruskal–Wallis test); Table 3).

Differences in community change rate between the habitats

The Bray–Curtis dissimilarity based mean community change rate values were the highest in the limnocorral (L) and somewhat lower in the metaphyton (M) and plankton (P) samples (Figs. 7b and 8b), but the ANOVA results did not show significant differences neither in the case of taxa (P = 0.3910), nor in the case of FGs (P = 0.4140; Table 3).

In contrast, there were significant differences in the incidence-based community change rate values (1-Jaccard similarity) (Table 3), indicating that the metaphyton (M) showed less changes than the isolated- (L) and non-isolated phytoplankton (P) in the case of taxa (P = 0.0248 for L–M and P = 0.0065 for M–P; Fig. 7d, Table 3). However, in the case of FGs the metaphyton (M) only showed significant difference from the non-isolated phytoplankton (P) (P = 0.0296 for M–P; Fig. 8d, Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated how metaphytic assemblages of the littoral vegetation affected the composition and diversity of pelagic phytoplankton in a small eutrophic pond. The relevance of this question is more pronounced in the case of small shallow lakes, where because of their high littoral-pelagial ratio the extended macrovegetation has a strong impact on the metabolism of the whole lake (Wetzel et al., 1972; Carpenter & Lodge, 1986). Macrophytes besides shaping the physical properties of the ecosystems and enable microgradients of resources to develop (Declerck et al., 2007; Wijewardene et al., 2022), have an array of complex interactions (competition, mutualism, commensalism) with their epi- and metaphytic microalgal assemblages (Koleszár et al., 2022; Mutinová et al., 2016; Roijackers et al., 2004). In the experimental pond, the littoral vegetation consisted primarily of N. alba and C. demersum. These species are quite widely distributed, C. demersum is an invasive cosmopolitan species (GBIF Secretariat, 2022; GISD, 2023) while N. alba is widespread in Europe and can be found in several other locations (GBIF Secretariat, 2022). Both species are associated with waters on a wide scale of trophic states (Brock, 1985; GISD, 2023) and can be dominant in oxbow lakes (Krasznai et al., 2010). Because of the shading effect of Nymphaea and the well-known allelopathic effect of Ceratophyllum on cyanobacteria and microalgae (Amorim et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2019), this vegetation is less favourable for the development of species rich metaphytic assemblages in comparison to Utricularia and Salvinia stands where more diverse metaphytic assemblages can develop (Fehér, 2003; Krasznai et al., 2008). Nevertheless, some studies have contradictory results concerning the relationship between macrophytes and phytoplankton diversity. For example Muylaert et al. (2010) found negative relationship between phytoplankton generic diversity and macrophyte cover in shallow lakes. The authors highlighted the importance of growing time, that is influenced by latitude (more diverse assemblages can develop at lower latitudes due to longer growing seasons). Furthermore, the paper stressed the importance of grazing by zooplankton and its changing importance along latitudinal gradient. In contrast Diniz et al. (2023) found that the presence of floating and submerged macrophytes increased species diversity under eutrophic conditions in tropical ponds. Van den Berg et al. (1998) highlighted that biomass changes and composition of algal assemblages are impacted by the density of macrophytes. They concluded that increased density of macrophytes promotes sedimentation loss of algae. Therefore, flagellated taxa that are able to reduce their sedimentation might be able to stay in the water column (e.g. Cryptomonas sp. and Rhodomonas sp.), while others may sink. Pełechata & Pełechaty (2010) showed that an emerged macrophyte [Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud.] overgrown by C. demersum had quite similar phytoplankton community composition as a C. demersum and N. alba dominated part of the water and the open water surface as well.

In our experimental setup the NMDS ordination clearly distinguished the three habitats, and both the ANOSIM and PERMANOVA indicated that the habitats show significant differences in terms of their microflora. These results supported our main hypothesis that metaphytic assemblages have an effect on the composition of the pelagial phytoplankton.

Not surprisingly some tychoplanktic elements, mostly diatoms from the TIB group [Achnanthidium minutissimum (Kützing) Czarnecki, Amphora pediculus (Kützing) Grunow ex Schmidt, Navicula veneta Kützing, Nitzschia dissipata (Kützing) Rabenhorst, etc. see Supplementary Table 2] were unique for the metaphyton. Differences, however, did not restrict exclusively to this group. We found larger functional redundancy of planktic FGs (J, W1, F, Lo,) in the metaphyton, than in the isolated part of the pond. These results are in accordance with previous findings (Borics et al., 2003). Investigating microflora of bog-lakes Borics et al. (2003) also experienced that planktic algae, especially those that lack capability of active locomotion were not present in the open water, but were abundant among the macrovegetation, where they settled on the surface of submerged plants, and avoided sinking to the bottom.

Among the FGs that showed high redundancy in the metaphyton, the W1 group deserves more attention. Small-celled dinoflagellates and euglenophytes constitute this group (Reynolds et al., 2002). We recorded 29 euglenophyte species in the studied pond of which 24 belonged to W1, and 5 (Trachelomonas spp.) to W2 group. Euglenophytes have long been considered as pond dwellers preferring eutrophic environments (Pringsheim, 1953, 1956; Wetzel, 1983). Recent studies highlighted their importance in epipelic environments (Round & Eaton, 1966; Hašler et al., 2008; Şahín et al., 2010; Poulíčková et al., 2014). Other authors (Marshall & Orr, 1948; Smayda et al., 2020) found that E. proxima Dangeard blooms were associated to oxic/anoxic boundary layer developed in meromictic lakes. Several recent findings (Burchardt et al., 2006; Padisák et al., 2003; Scheffer et al., 2006; Poniewozik & Juráň, 2018) revealed the importance of high macrophyte coverage for the development of rich euglenophyte assemblages. The above results suggest that there is still not enough knowledge on the autecology of euglenophytes to fully understand their occurrence and role in the metaphytic environments.

While richness values showed considerable differences among the habitats, there were no differences in the Shannon diversity values. The similar values in Pielou’s evenness referred to similarities in the abundance of dominant taxa. However, we note here that the use of Shannon diversity is controversial in the literature, because it combines evenness and richness into a univariate vector that is difficult to interpret (Borics et al., 2021). In addition to this, diversity metrics are not sensitive to species replacements and thus, they cannot display well smaller compositional differences (T-Krasznai et al., 2023 submitted to this volume).

In contrast to Shannon diversity, the Jaccard similarity index values indicated well the differences between the microflora of limnocorral (L) and the other two habitats (M, P), both for the species and FGs. These results support our suggestion that the metaphyton is a source of several species that occur in the open water and considerably contributes to its species and functional richness.

Several research highlights that phytoplankton in the temperate lakes show considerable compositional changes throughout a year (Reynolds, 1989; Padisák et al., 1998; Deng et al., 2020). These compositional alterations could be observed in all three habitats. Although we hypothesised that macrophytes mitigate stochastic environmental effects throughout the study period, therefore lower community change rate values were expected in the metaphyton, the results only partially supported this assumption. While Bray–Curtis dissimilarity based community change rate did not show significant differences, the incidence-based community change rate values (1-Jaccard index) supported the hypothesis in the case of taxa, indicating less changes in the metaphytic habitat (M) than in the isolated (L) and non-isolated phytoplankton (P). However, in the case of FGs, there were only significant difference between the metaphyton (M) and the non-isolated phytoplankton (P), which showed the largest community change during the study period. We think that these findings can be explained by the fact that the mass effect between the metaphyton and the open water phytoplankton is not a continuous process, but is affected by occasional water movements. The mass effect means a temporarily unpredictable and stochastic species input.

We should emphasise here that the strengths of the source-sink dynamics between the metaphyton and plankton is a size specific process. In small lentic standing waters, the nutrient uptake and the physical structure of macrophytes create microgradients in nutrient and light availability (Declerck et al., 2007). These differences allow the creation of several microhabitats, which enable high taxa- and functional diversity to develop. In contrast, in the case of large lakes, the wind-induced waves homogenise the microflora of the lake, including that of the littoral vegetation. In these systems, because the continuously mixed littoral cannot enrich the open water with metaphytic elements (Várbíró et al., 2017), the impact of the source-sink dynamic must be negligible.

Conclusion

Here we demonstrated that the microalgal flora of the littoral vegetation is neither a shaded, low biomass assemblage of euplanktic elements, nor an assemblage in which simply tichoplanktic elements prevail. Rather it consists of functionally and taxonomically diverse assemblages that enrich the phytoplankton of the open water with new elements. Understanding the main drivers of diversity of the metaphyton requires recognising the small environmental gradients that potentially develop among the macrophytes and reveal the autecology of species and FGs that exploit of these unique habitats.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abonyi, A., Z. Horváth & R. Ptacnik, 2018. Functional richness outperforms taxonomic richness in predicting ecosystem functioning in natural phytoplankton communities. Freshwater Biology 63: 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.13051.

Alahuhta, J., A. Kanninen, S. Hellsten, K.-M. Vuori, M. Kuoppala & H. Hämäläinen, 2013. Environmental and spatial correlates of community composition, richness and status of boreal lake macrophytes. Ecological Indicators 32: 172–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.03.031.

Amorim, C. A., R. H. de Moura-Falcão, C. R. Valença, V. R. de Souza & A. d0 Nascimento Moura, 2019. Allelopathic effects of the aquatic macrophyte Ceratophyllum demersum L. on phytoplankton species: contrasting effects between cyanobacteria and chlorophytes. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 31: e21. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2179-975X1419.

Baas-Becking, L. G. M. B., 1934. Geobiologie of inleiding tot de milieukunde, W.P. Van Stockum & Zoon.

Barko, J. W. & R. M. Smart, 1986. Sediment-related mechanisms of growth limitation in submersed macrophytes. Ecology 67: 1328–1340. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938689.

Behre, K., 1956. Die Algenbesiedlung einiger Seen um Bremen und Bremerhaven, Bremen.

Berger, W. H. & F. L. Parker, 1970. Diversity of planktonic foraminifera in deep sea sediments. Science 168: 1345–1347. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.168.3937.1345.

Bergström, A.-K., C. Bigler, U. Stensdotter & E. S. Lindström, 2008. Composition and dispersal of riverine and lake phytoplankton communities in connected systems with different water retention times. Freshwater Biology 53: 2520–2529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.02080.x.

Borics, G., B. Tóthmérész, I. Grigorszky, J. Padisák, G. Várbíró & S. Szabó, 2003. Algal assemblage types of bog-lakes in Hungary and their relation to water chemistry, hydrological conditions and habitat diversity. In Naselli-Flores, L., J. Padisák & M. T. Dokulil (eds), Phytoplankton and Equilibrium Concept: The Ecology of Steady-State Assemblages Springer, Dordrecht: 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2666-5_13.

Borics, G., G. Várbíró, I. Grigorszky, E. Krasznai, S. Szabó & K. T. Kiss, 2007. A new evaluation technique of potamo-plankton for the assessment of the ecological status of rivers. Large Rivers 17: 466–486. https://doi.org/10.1127/lr/17/2007/466.

Borics, G., A. Abonyi, N. Salmaso & R. Ptacnik, 2021. Freshwater phytoplankton diversity: models, drivers and implications for ecosystem properties. Hydrobiologia 848: 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04332-9.

Bortolini, J., A. Pineda, L. Rodrigues, S. Jati & L. Velho, 2017. Environmental and spatial processes influencing phytoplankton biomass along a reservoirs-river-floodplain lakes gradient: a metacommunity approach. Freshwater Biology 62: 1756–1767. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12986.

Bray, J. R. & J. T. Curtis, 1957. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecological Monographs 27: 326–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/1942268.

Brock, T. C., J. J. Boon & B. G. Paffen, 1985. The effects of the season and of water chemistry on the decomposition of Nymphaea alba L.; weight loss and pyrolysis mass spectrometry of the particulate matter. Aquatic Botany 22: 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3770(85)90001-4.

Burchardt, L., B. Messyasz & A. Stępniak, 2006. Diversity of phytoplankton community in Borusa and Grundela ponds. Teka Komisji Ochrony i Kształtowania Środowiska Przyrodniczego 3: 35–40.

Carpenter, S. R. & D. M. Lodge, 1986. Effects of submersed macrophytes on ecosystem processes. Aquatic Botany 26: 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3770(86)90031-8.

CEN 13946, 2003. Water quality. Guidance standard for the routinesampling and pretreatment of benthic diatoms from rivers.

CEN 15204, 2006. Water quality. Guidance standard on the enumerationof phytoplankton using inverted microscopy (Utermöhl technique).

Declerck, S., M. Vanderstukken, A. Pals, K. Muylaert & L. De Meester, 2007. Plankton biodiversity along a gradient of productivity and its mediation by macrophytes. Ecology 88: 2199–2210. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0048.1.

Deng, J., W. Zhang, B. Q. Qin, Y. Zhang, N. Salmaso & E. Jeppesen, 2020. Winter climate shapes spring phytoplankton development in non-ice-covered lakes: subtropical lake taihu as an example. Water Resources Research 56: e2019WR026680. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR026680.

Diniz, A. S., Ê. W. Dantas & A. do Nascimento Moura, 2023. The role of floating and submerged macrophytes in the phytoplankton taxonomic and functional diversity in two tropical reservoirs. Hydrobiologia 850: 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-022-05073-7.

Dong, J., M. Chang, C. Li, D. Dai & Y. Gao, 2019. Allelopathic effects and potential active substances of Ceratophyllum demersum L. on Chlorella vulgaris Beij. Aquatic Ecology 53: 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-019-09715-2.

Dvořák, S. J. & E. Liskova, 1970. A quantitative study on the macrofauna of stands of emergent vegetation in a carp pond of south-west Bohemia. Rozprovy Českosl. Akad. Věd. Řada Matem. Přírod. Věd 80: 63–114.

Ellner, S. P., R. E. Snyder, P. B. Adler & G. Hooker, 2022. Toward a “modern coexistence theory” for the discrete and spatial. Ecological Monographs 92: e1548. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1548.

Fehér, G., 2003. The desmid flora of some alkaline lakes and wetlands in Southern Hungary. Biologia 58: 671–683.

Fussmann, G. F., S. P. Ellner & N. G. Hairston, 2003. Evolution as a critical component of plankton dynamics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 270: 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2335.

GBIF Secretariat, 2022. GBIF backbone taxonomy. Checklist Dataset. https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei.

Global Invasive Species Database, 2023. Ceratophyllum demersum. http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Ceratophyllum+demersum.

Goldsborough, L. G. & G. G. C. Robinson, 1996. Patterns in wetlands. In Algal Ecology: Freshwater Benthic Ecosystems Academic Press, Cambridge: 77–117.

Görgényi, J., B. Tóthmérész, G. Várbíró, A. Abonyi, E. Krasznai, V. B-Béres & G. Borics, 2019. Contribution of phytoplankton functional groups to the diversity of a eutrophic oxbow lake. Hydrobiologia 830: 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-018-3878-3.

Gross, E. M., 2003. Allelopathy of aquatic autotrophs. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 22: 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/713610859.

Guiry, M. D. & G. M. Guiry, 2023. AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. https://www.algaebase.org

Hammer, Ø., D. A. T. Harper & P. D. Ryan, 2001. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4: 1–9.

Hašler, P., J. Štěpánková, J. Špačková, J. Neustupa, M. Kitner, P. Hekera, J. Veselá, J. Burian & A. Poulíčková, 2008. Epipelic cyanobacteria and algae: a case study from Czech ponds. Fottea 8: 133–146. https://doi.org/10.5507/fot.2008.012.

Levine, J. M. & M. M. Mayfield, 2012. Rethinking community assembly through the lens of coexistence theory. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 43: 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110411-160411.

Howell, E. T., M. A. Turner, R. L. France, M. B. Jackson & P. M. Stokes, 1990. Comparison of Zygnematacean (Chlorophyta) algae in the metaphyton of two acidic lakes. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 47: 1085–1092. https://doi.org/10.1139/f90-125.

Hsieh, T. C., K. H. Ma & A. Chao, 2016. iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7: 1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12613.

Hutchinson, G. E., 1975. Variations on a theme by Robert MacArthur. In Ecology and Evolution of Communities Harvard University Press, Cambridge: 492–521.

Jaccard, P., 1901. Distribution de la flore alpine dans le bassin des Dranses et dans quelques régions voisines. Bulletin De La Société Vaudoise Des Sciences Naturelles 37: 241–272.

Kelly, C. A., J. A. Amaral, M. A. Turner, J. W. M. Rudd, D. W. Schindler & M. P. Stainton, 1995. Disruption of sulfur cycling and acid neutralization in lakes at low pH. Biogeochemistry 28: 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02180680.

Koleszár, G., Z. Nagy, E. T. H. M. Peeters, G. Borics, G. Várbíró, S. Birk & S. Szabó, 2022. The role of epiphytic algae and grazing snails in stable states of submerged and of free-floating plants. Ecosystems 25: 1371–1383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-021-00721-w.

Krasznai, E., G. Fehér, G. Borics, G. Várbíró, I. Grigorszky & B. Tóthmérész, 2008. Use of desmids to assess the natural conservation value of a Hungarian oxbow (Malom-Tisza, NE-Hungary). Biologia 63: 928–935. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-008-0144-6.

Krasznai, E., G. Borics, G. Várbíró, A. Abonyi, J. Padisák, C. Deák & B. Tóthmérész, 2010. Characteristics of the pelagic phytoplankton in shallow oxbows. Hydrobiologia 639: 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-009-0027-z.

Leibold, M. & J. Chase, 2018. Metacommunity Ecology, Vol. 59. Princeton University Press, Princeton: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400889068.

Letten, A. D., P.-J. Ke & T. Fukami, 2017. Linking modern coexistence theory and contemporary niche theory. Ecological Monographs 87: 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1242.

Lu, J., S. E. Bunn & M. A. Burford, 2018. Nutrient release and uptake by littoral macrophytes during water level fluctuations. Science of the Total Environment 622–623: 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.199.

Marshall, S. M. & A. P. Orr, 1948. Further experiments on the fertilization of a sea Loch (Loch Craiglin). The effect of different plant nutrients on the phytoplankton. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 27: 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531540002542X.

Mason, N. W. H., D. Mouillot, W. G. Lee & J. B. Wilson, 2005. Functional richness, functional evenness and functional divergence: the primary components of functional diversity. Oikos 111: 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13886.x.

Moore, B. C., J. E. Lafer & W. H. Funk, 1994. Influence of aquatic macrophytes on phosphorus and sediment porewater chemistry in a freshwater wetland. Aquatic Botany 49: 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3770(94)90034-5.

Mouquet, N. & M. Loreau, 2003. Community patterns in source-sink metacommunities. The American Naturalist 162: 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1086/378857.

Mutinová, P. T., J. Neustupa, S. Bevilacqua & A. Terlizzi, 2016. Host specificity of epiphytic diatom (Bacillariophyceae) and desmid (Desmidiales) communities. Aquatic Ecology 50: 697–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-016-9587-y.

Muylaert, K., C. Pérez-Martínez, P. Sánchez-Castillo, T. L. Lauridsen, M. Vanderstukken, S. A. J. Declerck, K. Van der Gucht, J.-M. Conde-Porcuna, E. Jeppesen, L. De Meester & W. Vyverman, 2010. Influence of nutrients, submerged macrophytes and zooplankton grazing on phytoplankton biomass and diversity along a latitudinal gradient in Europe. Hydrobiologia 653: 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-010-0345-1.

Naselli-Flores, L. & R. Barone, 2012. Phytoplankton dynamics in permanent and temporary Mediterranean waters: is the game hard to play because of hydrological disturbance? In Salmaso, N., L. Naselli-Flores, L. Cerasino, G. Flaim, M. Tolotti & J. Padisák (eds), Phytoplankton Responses to Human Impacts at Different Scales Springer, Dordrecht: 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5790-5_12.

Padisák, J., L. Krienitz, W. Scheffler, R. Koschel, J. Kristiansen & I. Grigorszky, 1998. Phytoplankton succession in the oligotrophic Lake Stechlin (Germany) in 1994 and 1995. Hydrobiologia 369: 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017059624110.

Padisák, J., G. Borics, G. Fehér, I. Grigorszky, I. Oldal, A. Schmidt & Z. Zámbóné-Doma, 2003. Dominant species, functional assemblages and frequency of equilibrium phases in late summer phytoplankton assemblages in Hungarian small shallow lakes. Hydrobiologia 502: 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HYDR.0000004278.10887.40.

Padisák, J., L. Crossetti & L. Naselli-Flores, 2009. Use and misuse in the application of the phytoplankton functional classification: a critical review with updates. Hydrobiologia 621: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-008-9645-0.

Pełechata, A. & M. Pełechaty, 2010. The in situ influence of on a phytoplankton assemblage. Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies 39: 95–101. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10009-010-0004-x.

Pielou, E. C., 1966. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. Journal of Theoretical Biology 13: 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(66)90013-0.

Pikosz, M. & B. Messyasz, 2015. Composition and seasonal changes in filamentous algae in floating mats. Oceanological and Hydrobiological Studies 44: 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1515/ohs-2015-0026.

Poniewozik, M. & J. Juráň, 2018. Extremely high diversity of euglenophytes in a small pond in eastern Poland. Plant Ecology and Evolution 151: 18–34. https://doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.2018.1308.

Poulíčková, A., P. Dvořák, P. Mazalová & P. Hašler, 2014. Epipelic microphototrophs: an overlooked assemblage in lake ecosystems. Freshwater Science 33: 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/676313.

Pringsheim, E. G., 1953. Observations on some species of trachelomonas grown in culture. The New Phytologist 52: 238–266.

Pringsheim, E. G., 1956. Contributions towards a monograph of the genus euglena. Nova Acta Leopoldina 18: 1–168.

R Core Team, 2022. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Reynolds, C. S., 1989. Physical determinants of phytoplankton succession. In Sommer, U. (ed), Plankton Ecology: Succession in Plankton Communities. Brock/Springer Series in Contemporary Bioscience Springer, Berlin: 9–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-74890-5_2.

Reynolds, C. S., V. Huszár, C. Kruk, L. Naselli-Flores & S. Melo, 2002. Towards a functional classification of the freshwater phytoplankton. Journal of Plankton Research 24: 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/24.5.417.

Rimet, F., A. Canino, T. Chonova, J. Guéguen & A. Bouchez, 2023. Environmental filtering and mass effect are two important processes driving lake benthic diatoms: results of a DNA metabarcoding study in a large lake. Molecular Ecology 32: 124–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16737.

Roijackers, R. M. M., S. Szabó & M. Scheffer, 2004. Experimental analysis of the competition between algae and duckweed. Archiv Für Hydrobiologie 160: 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1127/0003-9136/2004/0160-0401.

Round, F. E., 1981. The Ecology of Algae, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge:

Round, F. E. & J. W. Eaton, 1966. Persistent, vertical-migration rhythms in benthic microflora: III. The rhythm of epipelic algae in a freshwater pond. Journal of Ecology 54: 609–615. https://doi.org/10.2307/2257806.

Şahín, B., B. Akar & Í. Bahceci, 2010. Species composition and diversity of epipelic algae in Balık Lake (Şavşat-Artvin, Turkey). Turkish Journal of Botany 34: 441–448. https://doi.org/10.3906/bot-0912-290.

Scheffer, M., G. J. Van Geest, K. Zimmer, E. Jeppesen, M. Søndergaard, M. G. Butler, M. A. Hanson, S. Declerck & L. De Meester, 2006. Small habitat size and isolation can promote species richness: second-order effects on biodiversity in shallow lakes and ponds. Oikos 112: 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2006.14145.x.

Shannon, C. E., 1948. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal 27: 379–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

Smayda, T. J., B. Thorne-Miller & C. Tomas, 2020. Annual phytoplankton cycle in a meromictic anoxic basin of a Rhode Island (USA) estuarine river. Hydrobiologia 847: 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-019-04113-z.

Szabó, B., E. Lengyel, J. Padisák & C. Stenger-Kovács, 2019. Benthic diatom metacommunity across small freshwater lakes: driving mechanisms, β-diversity and ecological uniqueness. Hydrobiologia 828: 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-018-3811-9.

T-Krasznai, E., V. B-Béres, V. Lerf, G. Várbíró, A. Abonyi, P. Török & G. Borics, 2023. Linear water column stratification and light availability determine phytoplankton diversity and composition in a hypertrophic oxbow lake. Hydrobiologia (submitted)

Van den Berg, M. S., H. Coops, M.-L. Meijer, M. Scheffer & J. Simons, 1998. Clear water associated with a dense chara vegetation in the shallow and turbid lake Veluwemeer, The Netherlands. In Jeppesen, E., M. Søndergaard & K. Christoffersen (eds), The Structuring Role of Submerged Macrophytes in Lakes Springer, New York: 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-0695-8_25.

Várbíró, G., J. Görgényi, B. Tóthmérész, J. Padisak, É. Hajnal & G. Borics, 2017. Functional redundancy modifies species-area relationship for freshwater phytoplankton. Ecology and Evolution 7: 9905–9913. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3512.

Vellend, M., 2010. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology 85: 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/652373.

Vellend, M., 2016. The Theory of Ecological Communities (MPB-57). Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1kt82jg.

Wetzel, R. G., 1983. Limnology, Saunders College Publishing, Philadelphia, London, Toronto: 767.

Wetzel, R. G., P. H. Rich, M. C. Miller & H. L. Allen, 1972. Metabolism of dissolved and particulate detrital carbon in a temperate hard- water lake. (COO-1599-58; CONF-720546-1). Michigan State University, Hickory Corners. W. K. Kellogg Biological Station. https://doi.org/10.2172/4614952.

Wijewardene, L., N. Wu, N. Fohrer & T. Riis, 2022. Epiphytic biofilms in freshwater and interactions with macrophytes: current understanding and future directions. Aquatic Botany 176: 103467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2021.103467.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (NKFIH OTKA) project no.: K-132150 and by the Scientific Board of the University of Nyíregyháza. Áron Lukács was supported by KKP-144068.

Funding

Open access funding provided by ELKH Centre for Ecological Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ÁL and GB drafted the key issues of this paper and wrote the manuscript. SS planned and created the limnocorral. SS, ET-K, JG, ZK and VB-B carried out the collecting and processing of the data. Statistical analyses were carried out by ÁL. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Research involving human and animal participants

No human participants and animals were involved in the research.

Additional information

Handling editor: Sidinei M. Thomaz

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Guest editors: Viktória B-Béres, Luigi Naselli-Flores, Judit Padisák & Gábor Borics / Trait-Based Approaches in Micro-Algal Ecology

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lukács, Á., Szabó, S., T-Krasznai, E. et al. Metaphyton contributes to open water phytoplankton diversity. Hydrobiologia 851, 941–958 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-023-05314-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-023-05314-3