Abstract

Amyloid transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis is a clinically heterogeneous and fatal disease that results from deposition of insoluble amyloid fibrils in various organs and tissues, causing progressive loss of function. The objective of this review is to increase awareness and diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis by improving recognition of its overlapping conditions, misdiagnosis, and multiorgan presentation. Cardiac manifestations include heart failure, atrial fibrillation, intolerance to previously prescribed antihypertensives, sinus node dysfunction, and atrioventricular block, resulting in the need for permanent pacing. Neurologic manifestations include progressive sensorimotor neuropathy (e.g., pain, weakness) and autonomic dysfunction (e.g., erectile dysfunction, chronic diarrhea, orthostatic hypotension). Non-cardiac red flags often precede the diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis and include musculoskeletal manifestations (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome, lumbar spinal stenosis, spontaneous rupture of the distal tendon biceps, shoulder and knee surgery). Awareness and recognition of the constellation of symptoms, including cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal manifestations, will help with early diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis and faster access to therapies, thereby slowing the progression of this debilitating disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Amyloid transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis is a progressively debilitating, clinically heterogeneous, and fatal disease caused by the buildup of transthyretin (TTR) amyloid fibrils in various organs and tissues, resulting in multisystem dysfunction particularly in the heart, along with the peripheral and autonomic nervous systems [1,2,3]. The diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis has been increasing over the last decade, and many patients have had musculoskeletal manifestations, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, distal biceps tendon rupture, idiopathic trigger finger, or spinal stenosis, any or all of which can precede by several years the cardiac or neurologic manifestations [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Disease progression in patients with ATTR amyloidosis is remarkably fast, resulting in significant impairment of function and irretrievable loss of quality of life [9,10,11,12,13]. With therapies available to slow disease progression, early recognition and diagnosis of patients with ATTR amyloidosis are important to facilitate early treatment. The aim of this review is to increase awareness of the constellation of symptoms in patients with ATTR amyloidosis—especially the non-cardiac symptoms that cardiologists and others may not traditionally associate with ATTR amyloidosis but that are key for identifying patients with this progressive, fatal disease.

Wild-type vs hereditary ATTR amyloidosis symptoms

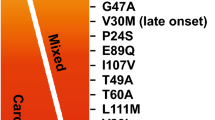

There are two forms of ATTR amyloidosis: wild type (ATTRwt) and hereditary (ATTRv [variant]). In ATTRwt amyloidosis, which was previously termed senile cardiac amyloidosis, a native non-mutated TTR protein misfolds into amyloid fibrils, primarily resulting in dysfunction of the heart that is characterized by restrictive cardiomyopathy; this is predominantly seen in males aged > 60 years [14,15,16]. Although ATTRwt amyloidosis typically manifests as cardiac symptoms, patients may also have signs and symptoms of sensorimotor neuropathy and autonomic neuropathy [14, 15], along with a clinical history of carpal tunnel syndrome, spinal stenosis, and other musculoskeletal manifestations [7]. ATTRv amyloidosis, originally called familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, is caused by a single amino acid substitution produced by a point mutation in the TTR gene. More than 130 mutations have been identified to date, with some mutations more often associated with either predominant polyneuropathy or cardiomyopathy; however, most patients experience a mixed phenotype with both neuropathic and cardiac symptoms [14, 15, 17,18,19]. The mechanisms by which mutations influence TTR aggregation or fibril morphology leading to organ dysfunction with such variable clinical presentations are poorly understood [20, 21]. In addition, phenotypic expression can be highly variable among individuals with a specific mutation, even within the same family [14].

Overlapping conditions and misdiagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis

ATTR amyloidosis is often overlooked or misdiagnosed in patients, at least early in its course, due to the non-specific, heterogeneous, multisystem presentation of the disease [3]. As the disease progresses, the symptoms and clinical manifestations of ATTR amyloidosis often mimic those of other more common diseases, further complicating and delaying diagnosis [22,23,24]. Thus, patients with ATTR amyloidosis could receive inappropriate treatments, such as chemotherapy for light-chain amyloidosis and intravenous immunoglobulins or steroids for immune polyneuropathies [3, 25, 26].

The signs and symptoms that should raise suspicion of ATTR amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) often overlap with other more commonly recognized cardiovascular diseases, such as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and light chain amyloidosis (Table 1) [25, 27,28,29]. Given that the life expectancy of a patient with ATTR-CM is 2 to 5 years after diagnosis, early and accurate diagnosis is key to forestalling disease progression. Recognizing the disease’s signs and symptoms, which affect multiple systems, may aid cardiologists in avoiding misdiagnosis.

Recognizing a constellation of ATTR amyloidosis symptoms

Early suspicion and recognition of ATTR amyloidosis can lead to an earlier diagnosis and treatment; there is evidence to suggest that a delay in treatment leads to irretrievable loss of quality of life and progression of the polyneuropathic and cardiac manifestations for most patients [3, 9,10,11,12,13]. Recognition of a constellation of symptoms may raise suspicion of amyloidosis early in its course (Fig. 1). Although patients may present with predominant symptoms of cardiomyopathy or progressive polyneuropathy, there can be substantial overlap, with many individuals presenting with a combination of both, as well as other abnormalities, such as musculoskeletal symptoms, orthostatic hypotension, erectile dysfunction, gastrointestinal abnormalities, and unexplained weight loss (Fig. 2) [14, 15]. Patients may also present with ocular manifestations and symptoms of nephropathy, which are discussed in other reviews [3, 30]. This phenotypic variability poses a considerable diagnostic challenge. ATTR amyloidosis should be considered in patients with signs and symptoms associated with cardiac, neurologic, or musculoskeletal manifestations, particularly when the constellation of those symptoms suggests that multiple organs are affected [3, 31].

A constellation of multisystem clinical signs and symptoms increases awareness of amyloid transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Recognition of non-cardiac symptoms clustered with cardiac and/or neurologic symptoms should prompt diagnostic testing and patient referral to a multidisciplinary team at an amyloidosis expert center

Symptoms of ATTR amyloidosis. Patients with ATTR amyloidosis may present with clinical signs or symptoms of cardiomyopathy or progressive polyneuropathy along with musculoskeletal symptoms and signs of autonomic dysfunction. ATTR amyloidosis should be considered for patients with cardiac, neurologic, or musculoskeletal manifestations, particularly when those symptoms suggest multiple organs are affected. ATTR amyloid transthyretin

Cardiovascular symptoms of ATTR amyloidosis

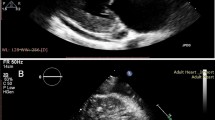

ATTR-CM is characterized by increased ventricular wall thickness, increased valve thickness, and interatrial and interventricular septum thickness that present as restrictive cardiomyopathy and progress to heart failure—initially in the setting of preserved ejection fraction, conduction system disturbances, and arrhythmias—with resulting impaired functional capacity, syncope, or palpitations [14, 15, 17, 32,33,34]. The signs and symptoms that should raise suspicion of ATTR-CM include a history of right-sided heart failure; heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (especially in men); intolerance to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNi), or beta-blockers; or atrial arrhythmias, conduction system disease, or need for a pacemaker (Table 2) [28, 29, 35, 36]. Additionally, heart failure in patients with ATTR amyloidosis progressively worsens over time, with patients experiencing decline in diastolic dysfunction, decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (~3% every 6 months), increased restrictive filling, and decline in functional capacity (~26 m decrease in 6-min walk distance every 6 months) [15, 27, 33, 37,38,39]. In patients with ATTRwt and ATTRv amyloidosis, troponin levels or N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels are elevated and increase over time; this is an indicator of clinical progression of heart failure [33, 36].

Neurologic symptoms of ATTR amyloidosis

Patients with amyloid polyneuropathy, such as ATTR amyloidosis, are frequently misdiagnosed with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) [24, 25, 40]. Other neuropathies confused with ATTR amyloidosis include paraproteinemic peripheral neuropathy, toxic peripheral neuropathy, vasculitic peripheral neuropathy, idiopathic axonal polyneuropathy, diabetic polyneuropathy, alcoholic neuropathy, paraneoplastic neuropathy, monoclonal gammopathy–associated neuropathy, and, more rarely, motor neuropathy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Table 1) [24, 25, 40]. Recently published guidelines review in greater detail the misleading features that often lead to these misdiagnoses [24]. Two key features of ATTR amyloidosis with polyneuropathy (ATTR-PN) distinguish it from the more common diabetic polyneuropathy: its progressive nature and, frequently, distal limb weakness. Diabetic polyneuropathy is typically a slow, progressive, and distal sensory neuropathy without much limb weakness (Table 3).

ATTR-PN is characterized by symmetrical length-dependent peripheral neuropathy; depending on the TTR mutation in the case of ATTRv amyloidosis, distal and occasionally proximal limb weakness may be prominent [3, 19]. As the disease progresses through each stage, the pattern of progression and class of nerve fiber impacted is reflected through heterogeneous clinical manifestations experienced by the patient with ATTR-PN [19, 41,42,43]. Early symptoms of ATTR-PN include burning pain, especially in younger patients; older patients experience burning pain, numbness, and loss of pain and temperature sensation, whereas the ability to perceive touch pressure and joint position is relatively preserved [3, 41]. Examination of nerve fiber involvement at this stage demonstrates degeneration of unmyelinated and small myelinated nerve fibers more than large myelinated fibers [41]. As ATTR-PN progresses, muscle weakness increases, especially in the lower limbs; patients with ATTR-PN suffer from progressive lower limb numbness, weakness, and gait imbalance [15, 43,44,45].

In addition to signs and symptoms of sensorimotor neuropathy, autonomic dysfunction is observed early in the course of ATTR amyloidosis and can precede motor impairment, but it often goes unrecognized [41, 46, 47]. Furthermore, in cases of severe autonomic dysfunction with reduced sympathetic function, the signs and symptoms of heart failure can be masked [48]. Autonomic neuropathy can manifest as orthostatic hypotension, recurrent urinary tract infection, erectile dysfunction, and/or gastrointestinal disturbances [3, 14, 15, 49]. Orthostatic hypotension, which is commonly reported as a symptom of ATTR amyloidosis, may manifest as dizziness or fainting when standing up, blurred vision, confusion, or light-headedness [15, 17, 46]. Meanwhile, gastrointestinal disturbances may include nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea (possibly alternating with constipation), or fecal incontinence and unintentional weight loss [3, 14, 15, 49].

Musculoskeletal manifestations of ATTR amyloidosis

Patients with ATTR amyloidosis may develop musculoskeletal manifestations 5 to 15 years prior to other symptoms (Fig. 3) [4, 7, 50, 51]. Numerous studies have reported the presence of ATTR amyloid in tissue removed during orthopedic surgeries, including the flexor tenosynovium, rotator cuff tendons, and ligamentum flavum [52, 53]. Rotator cuff surgery has been predominately reported in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis [53]. Carpal tunnel syndrome, the most common non-cardiac manifestation in patients with ATTR-CM, often presents years before a diagnosis of ATTRwt or ATTRv amyloidosis [4, 15, 37, 51, 54]. Carpal tunnel syndrome is caused by median nerve compression resulting in numbness, tingling sensations, or hand weakness. A recent study found that 10.2% of patients with bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome tested positive for amyloid deposits [6]. Of the 10 patients identified in the study, five were diagnosed with ATTRwt amyloidosis and two with ATTRv amyloidosis, and several also had a clinical history of trigger finger, lumbar spinal stenosis, or biceps tendon rupture [6]. Trigger finger due to amyloidosis is thought to occur when amyloid fibrils deposit in connective tissue, causing restricted movement of the flexor tendon, which then results in the finger being stuck in a bent position. The coexistence of trigger finger and carpal tunnel syndrome was also reported in members of a Japanese family with ATTRv amyloidosis [8]. In addition, a clinical history of lumbar spinal stenosis has been reported by several studies in patients with ATTRwt and ATTRv amyloidosis [5, 6, 53, 55]. Similarly, rupture of the distal biceps tendon (also known as Popeye sign) can be an early sign of amyloidosis; in patients aged >50 years, Popeye sign should raise suspicion of ATTR amyloidosis [56].

Musculoskeletal manifestations associated with ATTR amyloidosis. Buildup of TTR amyloid fibrils has been detected in tissue-resulting musculoskeletal manifestations, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, spinal stenosis, distal biceps tendon rupture, orthopedic surgery, or idiopathic trigger finger. Patients with ATTR amyloidosis may experience musculoskeletal signs and symptoms years prior to cardiac or neurologic manifestations. ATTR amyloid transthyretin; TTR transthyretin

Orthopedic surgery is significantly more common in patients with ATTR-CM compared with the general population [57]. Arthroplasty typically occurs over 6 to 8 years before diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis [57]. One study found that 25.9% (28/108) and 18.8% (12/64) of patients with ATTRwt and ATTRv amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, respectively, underwent hip or knee arthroplasty [57]. In addition, rotator cuff repair occurred in 9.9% of patients with ATTR amyloidosis [53, 57]. A history of a constellation of these musculoskeletal syndromes and surgeries in a patient along with cardiac or neurologic symptoms should raise clinical suspicion and prompt physicians to screen for ATTR amyloidosis [7].

Implementation of screening for ATTR amyloidosis in clinical practice

Cardiologists should screen for ATTR amyloidosis in patients with clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of multisystem involvement, particularly those with the constellation of cardiac, neurologic, and musculoskeletal manifestations described in this review. Given the multisystemic nature of ATTR amyloidosis, a multidisciplinary approach to assessment, diagnosis, and management of patients is recommended by the guidelines [24, 28]. The assessment of patients with cardiac symptoms should include noninvasive or invasive procedures, as described elsewhere [28, 30, 58, 59].

It can be challenging to identify ATTR amyloidosis given the diversity of diagnostic clues that can manifest in a patient over time (across many years). As cardiac amyloidosis is present in 10% to 15% of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [27, 33, 58, 60], the addition of screening questions and a check of multiple symptoms could help to identify patients with ATTR amyloidosis (Fig. 4).

Constellation of symptoms checklist for cardiac ATTR amyloidosis. Healthcare practitioners should evaluate patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction for a clinical history of carpal tunnel syndrome or lumbar spinal stenosis, along with progressive neuropathy or autonomic dysfunction. Clustering of these clinical signs and symptoms should prompt screening for cardiac amyloidosis and trigger referral to a multidisciplinary team at an amyloidosis expert center. ATTR amyloid transthyretin

Conclusion

Awareness of the non-cardiac symptoms that cluster with cardiac and neurologic symptoms can unmask a diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis and prompt referral to a center with expertise in this disease (Fig. 4) [3, 24, 28]. Because ATTR amyloidosis is now a treatable disease, recognizing the constellation of associated signs and symptoms, including those that are neurologic and musculoskeletal, is important because early treatment will make a meaningful impact on a patient’s quality of life, autonomy, and physical function [9,10,11,12,13].

References

Costa PP, Figueira AS, Bravo FR (1978) Amyloid fibril protein related to prealbumin in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75:4499–4503

Saraiva MJ, Birken S, Costa PP, Goodman DS (1984) Amyloid fibril protein in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, Portuguese type. Definition of molecular abnormality in transthyretin (prealbumin). J Clin Invest 74:104–119

Conceicao I, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Obici L, Schmidt HH, Simoneau D, Ong ML, Amass L (2016) “Red-flag” symptom clusters in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 21:5–9

Nakagawa M, Sekijima Y, Yazaki M, Tojo K, Yoshinaga T, Doden T, Koyama J, Yanagisawa S, Ikeda S (2016) Carpal tunnel syndrome: a common initial symptom of systemic wild-type ATTR (ATTRwt) amyloidosis. Amyloid 23:58–63

Ikram A, Donnelly JP, Sperry BW, Samaras C, Valent J, Hanna M (2018) Diflunisal tolerability in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: a single center’s experience. Amyloid 25:197–202

Sperry BW, Reyes BA, Ikram A, Donnelly JP, Phelan D, Jaber WA, Shapiro D, Evans PJ, Maschke S, Kilpatrick SE, Tan CD, Rodriguez ER, Monteiro C, Tang WHW, Kelly JW, Seitz WH Jr, Hanna M (2018) Tenosynovial and cardiac amyloidosis in patients undergoing carpal tunnel release. J Am Coll Cardiol 72:2040–2050

Donnelly JP, Hanna M, Sperry BW, Seitz WH Jr (2019) Carpal tunnel syndrome: a potential early, red-flag sign of amyloidosis. J Hand Surg Am 44:868–876

Uotani K, Kawata A, Nagao M, Mizutani T, Hayashi H (2007) Trigger finger as an initial manifestation of familial amyloid polyneuropathy in a patient with Ile107Val TTR. Intern Med 46:501–504

Coelho T, Yarlas A, Waddington-Cruz M, White MK, Sikora Kessler A, Lovley A, Pollock M, Guthrie S, Ackermann EJ, Hughes SG, Karam C, Khella S, Gertz M, Merlini G, Obici L, Schmidt HH, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJB, Brannagan Iii TH, Conceicao I, Benson MD, Berk JL (2019) Inotersen preserves or improves quality of life in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. J Neurol 267:1070–1079

Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk JL, Lin KP, Vita G, Attarian S, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Mezei MM, Campistol JM, Buades J, Brannagan TH 3rd, Kim BJ, Oh J, Parman Y, Sekijima Y, Hawkins PN, Solomon SD, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Gandhi PJ, Goyal S, Chen J, Strahs AL, Nochur SV, Sweetser MT, Garg PP, Vaishnaw AK, Gollob JA, Suhr OB (2018) Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 379:11–21

Benson MD, Waddington-Cruz M, Berk JL, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Wang AK, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Barroso FA, Merlini G, Obici L, Scheinberg M, Brannagan TH 3rd, Litchy WJ, Whelan C, Drachman BM, Adams D, Heitner SB, Conceicao I, Schmidt HH, Vita G, Campistol JM, Gamez J, Gorevic PD, Gane E, Shah AM, Solomon SD, Monia BP, Hughes SG, Kwoh TJ, McEvoy BW, Jung SW, Baker BF, Ackermann EJ, Gertz MA, Coelho T (2018) Inotersen treatment for patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 379:22–31

Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz M, Kristen AV, Grogan M, Witteles R, Damy T, Drachman BM, Shah SJ, Hanna M, Judge DP, Barsdorf AI, Huber P, Patterson TA, Riley S, Schumacher J, Stewart M, Sultan MB, Rapezzi C (2018) Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 379:1007–1016

Obici L, Berk JL, Gonzalez-Duarte A, Coelho T, Gillmore J, Schmidt HH, Schilling M, Yamashita T, Labeyrie C, Brannagan TH 3rd, Ajroud-Driss S, Gorevic P, Kristen AV, Franklin J, Chen J, Sweetser MT, Wang JJ, Adams D (2020) Quality of life outcomes in APOLLO, the phase 3 trial of the RNAi therapeutic patisiran in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Amyloid 27:1–10

Coelho T, Maurer MS, Suhr OB (2013) THAOS - The Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey: initial report on clinical manifestations in patients with hereditary and wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Med Res Opin 29:63–76

Maurer MS, Hanna M, Grogan M, Dispenzieri A, Witteles R, Drachman B, Judge DP, Lenihan DJ, Gottlieb SS, Shah SJ, Steidley DE, Ventura H, Murali S, Silver MA, Jacoby D, Fedson S, Hummel SL, Kristen AV, Damy T, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Coelho T, Mundayat R, Suhr OB, Waddington CM, Rapezzi C (2016) Genotype and phenotype of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: THAOS (Transthyretin Amyloid Outcome Survey). J Am Coll Cardiol 68:161–172

Ruberg FL, Berk JL (2012) Transthyretin (TTR) cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation 126:1286–1300

Rapezzi C, Quarta CC, Obici L, Perfetto F, Longhi S, Salvi F, Biagini E, Lorenzini M, Grigioni F, Leone O, Cappelli F, Palladini G, Rimessi P, Ferlini A, Arpesella G, Pinna AD, Merlini G, Perlini S (2013) Disease profile and differential diagnosis of hereditary transthyretin-related amyloidosis with exclusively cardiac phenotype: an Italian perspective. Eur Heart J 34:520–528

Rowczenio DM, Noor I, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Whelan C, Hawkins PN, Obici L, Westermark P, Grateau G, Wechalekar AD (2014) Online registry for mutations in hereditary amyloidosis including nomenclature recommendations. Hum Mutat 35:E2403–E2412

Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL, Cruz MW, Ericzon BG, Ikeda S, Lewis WD, Obici L, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Rapezzi C, Said G, Salvi F (2013) Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis 8:31

Schmidt M, Wiese S, Adak V, Engler J, Agarwal S, Fritz G, Westermark P, Zacharias M, Fandrich M (2019) Cryo-EM structure of a transthyretin-derived amyloid fibril from a patient with hereditary ATTR amyloidosis. Nat Commun 10:5008

Schonhoft JD, Monteiro C, Plate L, Eisele YS, Kelly JM, Boland D, Parker CG, Cravatt BF, Teruya S, Helmke S, Maurer M, Berk J, Sekijima Y, Novais M, Coelho T, Powers ET, Kelly JW (2017) Peptide probes detect misfolded transthyretin oligomers in plasma of hereditary amyloidosis patients. Sci Transl Med 9:eaam7621

Lane T, Bangova A, Fontana M, Hutt DF, Strehina SG, Whelan CJ, Hawkins PN (2015) Quality of life in ATTR amyloidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 10(Suppl 1):026

Lousada I, Comenzo RL, Landau H, Guthrie S, Merlini G (2015) Patient experience with hereditary and senile systemic amyloidoses: a survey from the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. Orphanet J Rare Dis 10(Suppl 1):P22

Adams D, Ando Y, Beirao JM, Coelho T, Gertz MA, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN, Lousada I, Suhr OB, Merlini G (2020) Expert consensus recommendations to improve diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis with polyneuropathy. J Neurol. Online ahead of print

Cortese A, Vegezzi E, Lozza A, Alfonsi E, Montini A, Moglia A, Merlini G, Obici L (2017) Diagnostic challenges in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis with polyneuropathy: avoiding misdiagnosis of a treatable hereditary neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88:457–458

Karam C, Dimitrova D, Heitner SB (2019) Misdiagnosis of hATTR amyloidosis: a single US site experience. Amyloid 27:69–70

Gonzalez-Lopez E, Gallego-Delgado M, Guzzo-Merello G, de Haro-Del Moral FJ, Cobo-Marcos M, Robles C, Bornstein B, Salas C, Lara-Pezzi E, Alonso-Pulpon L, Garcia-Pavia P (2015) Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis as a cause of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 36:2585–2594

Maurer MS, Bokhari S, Damy T, Dorbala S, Drachman BM, Fontana M, Grogan M, Kristen AV, Lousada I, Nativi-Nicolau J, Cristina Quarta C, Rapezzi C, Ruberg FL, Witteles R, Merlini G (2019) Expert consensus recommendations for the suspicion and diagnosis of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Circ Heart Fail 12:e006075

Narotsky DL, Castano A, Weinsaft JW, Bokhari S, Maurer MS (2016) Wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: novel insights from advanced imaging. Can J Cardiol 32:1166.e1-1166.e10

Gertz M, Adams D, Ando Y, Beirão JM, Bokhari S, Coelho T, Comenzo RL, Damy T, Dorbala S, Drachman BM, Fontana M, Gillmore JD, Grogan M, Hawkins PN, Lousada I, Kristen AV, Ruberg FL, Suhr OB, Maurer MS, Nativi-Nicolau J, Quarta CC, Rapezzi C, Witteles R, Merlini G (2020) Avoiding misdiagnosis: expert consensus recommendations for the suspicion and diagnosis of transthyretin amyloidosis for the general practitioner. BMC Fam Pract 21:198

Lousada I, Maurer M, Warner M, Guthrie S, Hsu K, M. G, (2017) Amyloidosis research consortium cardiac amyloidosis survey: results from patients with ATTR amyloidosis and their caregivers. Orphanet J Rare Dis 12(Suppl 1):165

Damy T, Costes B, Hagege AA, Donal E, Eicher JC, Slama M, Guellich A, Rappeneau S, Gueffet JP, Logeart D, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Bouvaist H, Huttin O, Mulak G, Dubois-Rande JL, Goossens M, Canoui-Poitrine F, Buxbaum JN (2016) Prevalence and clinical phenotype of hereditary transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in patients with increased left ventricular wall thickness. Eur Heart J 37:1826–1834

Ruberg FL, Maurer MS, Judge DP, Zeldenrust S, Skinner M, Kim AY, Falk RH, Cheung KN, Patel AR, Pano A, Packman J, Grogan DR (2012) Prospective evaluation of the morbidity and mortality of wild-type and V122I mutant transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Cardiac Study (TRACS). Am Heart J 164:222-228.e221

Benson MD, Teague SD, Kovacs R, Feigenbaum H, Jung J, Kincaid JC (2011) Rate of progression of transthyretin amyloidosis. Am J Cardiol 108:285–289

Brunjes DL, Castano A, Clemons A, Rubin J, Maurer MS (2016) Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in older Americans. J Card Fail 22:996–1003

Castano A, Drachman BM, Judge D, Maurer MS (2015) Natural history and therapy of TTR-cardiac amyloidosis: emerging disease-modifying therapies from organ transplantation to stabilizer and silencer drugs. Heart Fail Rev 20:163–178

Connors LH, Sam F, Skinner M, Salinaro F, Sun F, Ruberg FL, Berk JL, Seldin DC (2016) Heart failure resulting from age-related cardiac amyloid disease associated with wild-type transthyretin: a prospective, observational cohort study. Circulation 133:282–290

Mohammed SF, Mirzoyev SA, Edwards WD, Dogan A, Grogan DR, Dunlay SM, Roger VL, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Zeldenrust SR, Redfield MM (2014) Left ventricular amyloid deposition in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2:113–122

Witteles RM, Bokhari S, Damy T, Elliott PM, Falk RH, Fine NM, Gospodinova M, Obici L, Rapezzi C, Garcia-Pavia P (2019) Screening for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy in everyday practice. JACC Heart Fail 7:709–716

Lozeron P, Mariani LL, Dodet P, Beaudonnet G, Theaudin M, Adam C, Arnulf B, Adams D (2018) Transthyretin amyloid polyneuropathies mimicking a demyelinating polyneuropathy. Neurology 91:e143–e152

Dyck PJ, Lambert EH (1969) Dissociated sensation in amylidosis. Compound action potential, quantitative histologic and teased-fiber, and electron microscopic studies of sural nerve biopsies. Arch Neurol 20:490–507

Kim DH, Zeldenrust SR, Low PA, Dyck PJ (2009) Quantitative sensation and autonomic test abnormalities in transthyretin amyloidosis polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve 40:363–370

Coelho T, Vinik A, Vinik EJ, Tripp T, Packman J, Grogan DR (2017) Clinical measures in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve 55:323–332

Carr AS, Pelayo-Negro AL, Evans MR, Laura M, Blake J, Stancanelli C, Iodice V, Wechalekar AD, Whelan CJ, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN, Reilly MM (2016) A study of the neuropathy associated with transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) in the UK. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87:620–627

Adams D (2013) Recent advances in the treatment of familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 6:129–139

Gonzalez-Duarte A (2019) Autonomic involvement in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR amyloidosis). Clin Auton Res 29:245–251

Benson MD, Kincaid JC (2007) The molecular biology and clinical features of amyloid neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 36:411–423

Abramov D, Weimer LH, Marboe CC, Shimbo D, King DL, Maurer MS (2009) Absence of heart failure in severe cardiac and autonomic amyloidosis: the essential role of sympathetic activation and venous tone in the development of the congestive heart failure syndrome. Congest Heart Fail 15:288–290

Wixner J, Mundayat R, Karayal ON, Anan I, Karling P, Suhr OB, investigators T, (2014) THAOS: gastrointestinal manifestations of transthyretin amyloidosis - common complications of a rare disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9:61

Mazzeo A, Russo M, Di Bella G, Minutoli F, Stancanelli C, Gentile L, Baldari S, Carerj S, Toscano A, Vita G (2015) Transthyretin-related familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP): a single-center experience in Sicily, an Italian endemic area. J Neuromuscul Dis 2:S39–S48

Papoutsidakis N, Miller EJ, Rodonski A, Jacoby D (2018) Time course of common clinical manifestations in patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: delay from symptom onset to diagnosis. J Card Fail 24:131–133

Sekijima Y, Uchiyama S, Tojo K, Sano K, Shimizu Y, Imaeda T, Hoshii Y, Kato H, Ikeda S (2011) High prevalence of wild-type transthyretin deposition in patients with idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: a common cause of carpal tunnel syndrome in the elderly. Hum Pathol 42:1785–1791

Sueyoshi T, Ueda M, Jono H, Irie H, Sei A, Ide J, Ando Y, Mizuta H (2011) Wild-type transthyretin-derived amyloidosis in various ligaments and tendons. Hum Pathol 42:1259–1264

Pinney JH, Whelan CJ, Petrie A, Dungu J, Banypersad SM, Sattianayagam P, Wechalekar A, Gibbs SD, Venner CP, Wassef N, McCarthy CA, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ (2013) Senile systemic amyloidosis: clinical features at presentation and outcome. J Am Heart Assoc 2:e000098

Yanagisawa A, Ueda M, Sueyoshi T, Okada T, Fujimoto T, Ogi Y, Kitagawa K, Tasaki M, Misumi Y, Oshima T, Jono H, Obayashi K, Hirakawa K, Uchida H, Westermark P, Ando Y, Mizuta H (2015) Amyloid deposits derived from transthyretin in the ligamentum flavum as related to lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Mod Pathol 28:201–207

Geller HI, Singh A, Alexander KM, Mirto TM, Falk RH (2017) Association between ruptured distal biceps tendon and wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. JAMA 318:962–963

Rubin J, Alvarez J, Teruya S, Castano A, Lehman RA, Weidenbaum M, Geller JA, Helmke S, Maurer MS (2017) Hip and knee arthroplasty are common among patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis, occurring years before cardiac amyloid diagnosis: can we identify affected patients earlier? Amyloid 24:226–230

Ruberg FL, Grogan M, Hanna M, Kelly JW, Maurer MS (2019) Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 73:2872–2891

Kittleson MM, Maurer MS, Ambardekar AV, Bullock-Palmer RP, Chang PP, Eisen HJ, Nair AP, Nativi-Nicolau J, Ruberg FL (2020) Cardiac amyloidosis: evolving diagnosis and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 142:e7–e22

Senapati A, Sperry BW, Grodin JL, Kusunose K, Thavendiranathan P, Jaber W, Collier P, Hanna M, Popovic ZB, Phelan D (2016) Prognostic implication of relative regional strain ratio in cardiac amyloidosis. Heart 102:748–754

Koike H, Tanaka F, Hashimoto R, Tomita M, Kawagashira Y, Iijima M, Fujitake J, Kawanami T, Kato T, Yamamoto M, Sobue G (2012) Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:152–158

Yarlas A, Gertz MA, Dasgupta NR, Obici L, Pollock M, Ackermann EJ, Lovley A, Kessler AS, Patel PA, White MK, Guthrie SD (2019) Burden of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis on quality of life. Muscle Nerve 60:169–175

Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, Smith AL, Feldman EL (2012) Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol 11:521–534

Yang H, Sloan G, Ye Y, Wang S, Duan B, Tesfaye S, Gao L (2020) New perspective in diabetic neuropathy: from the periphery to the brain, a call for early detection, and precision medicine. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10:929

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Monique N. O’Leary, PhD, of ApotheCom (San Francisco, CA, USA).

Funding

Medical writing support was funded by Akcea Therapeutics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. All the authors contributed substantial intellectual content to drafts of the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jose N. Nativi-Nicolau reports funding for clinical trials from Pfizer, Akcea Therapeutics, and Eidos; educational grants from Pfizer; and consulting fees from Pfizer, Eidos, Akcea Therapeutics, and Alnylam. Chafic Karam reports consulting/educational activities for Akcea Therapeutics, Alexion, Alnylam, Argenx, Biogen, CSL Behring, Medscape, and Sanofi Genzyme; and has received research grants from Sanofi Genzyme and Akcea Therapeutics. Sami Khella reports honoraria from Akcea Therapeutics and Alnylam. Mathew S. Maurer reports grants from Pfizer and Alnylam; and personal fees from Pfizer, Eidos, GlaxoSmithKline, Prothena, Akcea Therapeutics, and Ionis.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nativi-Nicolau, J.N., Karam, C., Khella, S. et al. Screening for ATTR amyloidosis in the clinic: overlapping disorders, misdiagnosis, and multiorgan awareness. Heart Fail Rev 27, 785–793 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-021-10080-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-021-10080-2