Abstract

Some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have tested the efficacy of beta-blockers as prophylactic agents on cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity; however, the quality of this evidence remains undetermined. This systematic review and meta-analysis study aims to evaluate the prophylactic effects of beta-blockers, especially carvedilol, on chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. RCTs were identified by searching the MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (OvidSP), Cochrane CENTRAL (OvidSP), etc., until December 2017. Inclusion criteria were randomized clinical trial and adult cancer patients started beta-blockers before chemotherapy. We evaluated the mean differences (MD) by fixed- or random-effects model and the odds ratio by Peto’s method. Primary outcome was the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of patients after chemotherapy, and secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality, clinically overt cardiotoxicity, and other echocardiographic measurements. In total, we included six RCTs that used carvedilol as a prophylactic agent in patients receiving chemotherapy. The LVEF was not significantly distinct between those using carvedilol and placebo after chemotherapy (MD, 1.74; 95% confidence interval (CI), − 0.18 to 3.66; P = 0.08). The incidence of clinically overt cardiotoxicity was lower in the carvedilol group compared with the control group (Peto OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.20–0.89; P = 0.02). Furthermore, after chemotherapy, the LV end-diastolic diameter did not increase in the carvedilol group compared with the placebo group (MD, − 1.41; 95% CI, − 2.32 to − 0.50; P = 0.002). The prophylactic use of carvedilol exerted no impact on the early asymptomatic LVEF decrease but seemed to attenuate the frequency of clinically overt cardiotoxicity and prevent ventricular remodeling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent advancements in cancer treatment have remarkably improved the overall survival of patients with cancer [1]. However, chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity has been related to unfavorable prognosis in cancer survivors [2, 3], which has put oncologists into a therapeutic dilemma to maintain a balance between the antitumor efficacy and cardiac injury.

Heterogeneous factors contributing to chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity are cumulative anthracycline doses [4], adjunct therapy with trastuzumab [5, 6], prior radiotherapy [7], preexisting cardiovascular risks (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) [8, 9], and age [10]. Multiple mechanisms are associated with anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity; however, the most extensively accepted mechanism seems to be the generation of oxygen free radicals, which cause cardiomyocyte damage and apoptosis [11].

Lately, various efforts have been made to attenuate chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, including early detection of subclinical toxicity, development of derivatives [12], and the prophylactic use of cardioprotectants. The effects of cardioprotective beta-blockers have been tested in multiple animal experiments and clinically randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The primary mechanism associated with beta-blockers is reduction of oxidative stress and apoptosis [13, 14]. Carvedilol is a nonselective β and α1 adrenergic antagonist and has been proven to be cardioprotective not only through the intrinsic β-blocking effect (attenuating the sympathetic activity and cardiac remodeling) [15] but also the additional antioxidant and anti-inflammation properties compared with other beta-blockers [16, 17]. In particular, carvedilol can protect the myocardium without interfering with the antineoplastic efficacy of anthracyclines [18]. Although several beta-blockers have been tested through clinical RCTs, the number of enrolled patients was limited, and the results remained debatable. This study aims to evaluate the prophylactic effects of beta-blockers, especially carvedilol, on chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity by systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [19]. This study was prospectively registered with the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews (registration number: CRD42018086747).

Search strategy

We systematically searched MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Ovid SP), Cochrane CENTRAL (Ovid SP), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, as well as two Chinese medical databases, CNKI and WANFANG, until December 2017. In addition, a follow-up search was conducted for ongoing trials. The search strategy comprised a combination of Medical Subject Headings terms and free-text terms, primarily including “carvedilol,” “beta-blockers,” “anthracycline,” “chemotherapy,” “cardiotoxicity,” “cardiomyopathy,” and “heart failure.” Furthermore, we reviewed the reference lists of relevant studies and review articles. Of note, we limited the search to human beings without any language restriction.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients with cancer aged > 18 years due to receive chemotherapy; (b) beta-blockers used against the cardiotoxic effect of chemotherapy in a prophylactic setting (started before chemotherapy); (c) prospective RCT study design; and (d) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) assessed both at the baseline and post-chemotherapy. We excluded studies in which beta-blockers were used concomitantly with other cardioprotective agents, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

Data extraction and study quality assessment were performed per the PRISMA statement [19]. For systematic review, the following data and information were extracted: study design, age, gender, sample size, type of cancer, cumulative anthracycline doses, beta-blockers, follow-up time, baseline LVEF, and outcomes. The primary outcome was LVEF after chemotherapy, and secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality, clinically overt cardiotoxicity, and other cardiac measurements (e.g., E/A ratio and LV chamber size).

The quality of studies was assessed per the Cochrane risk of bias tool [20]. The adequacy of blinding was ascertained by whether cardiac measurements were assessed by a third person blinded to patients’ information. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. For key information that was not reported in the articles, we contacted the authors by e-mails.

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analyses using Review Manager (V.5.3, Cochrane) and Stata 13.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Q test and I2 statistics (I2 > 50% suggested substantial heterogeneity). In the absence of considerable heterogeneity, the fixed effects model was selected to obtain the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI); else, the random effects model was used. For comparing the risk of adverse events and mortality in patients and control subjects, we used Peto’s one-step odds ratio method, which is the least biased and most potent method when event rates were low, per the Cochrane handbook [21]. We considered P < 0.05 as statistically significant. In addition, the Galbraith plot and sensitivity analysis were conducted to determine the primary source of heterogeneity and ascertain the stability of the statistical results. Publication bias was assessed by Egger’s test. Although we planned to perform subgroup analysis, trials were insufficient.

Results

Search results

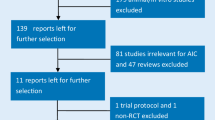

Initially, our comprehensive search yielded 1853 articles. We excluded duplicates and other 1628 articles after screening the titles and abstracts. We scrutinized the full texts of the remaining 27 studies, of which 17 were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1). Overall, we included 10 studies (6 on carvedilol, 1 on nebivolol, 2 on metoprolol, and 1 on bisoprolol). We analyzed the statistical data from six studies on carvedilol.

Study and patient characteristics

For 10 studies, 775 patients were included (male/female, 101/674; average age, 48.6 years) with various malignancies, including breast cancer, lymphoma (non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin), leukemia, and others, among which the rate of breast cancer was the highest. In fact, six studies exclusively included patients with breast cancer. All patients received anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. Patients received a relatively high cumulative anthracycline dose (> 550 mg/m2) in four studies and a relatively low dose in six studies. Patients in Pituskin’s study [22] received trastuzumab as an adjunct therapy. And all patients exhibited normal LVEF (> 50%) at the baseline with no history of heart failure symptoms or coronary condition. In addition, all patients started beta-blockers (carvedilol [n = 182], nebivolol [n = 27], bisoprolol [n = 31], and metoprolol [n = 74]) before the initiation or on the first day of chemotherapy and continued until the end of the study. The median follow-up duration was 6 months (range, 10–61 weeks). Each study comprised an age- and a sex-matched control group receiving placebo. The left ventricular function was assessed mostly by 2D echocardiogram, except two studies using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging [22, 23] (Table 1).

Effects of carvedilol

Asymptomatic LVEF decrease

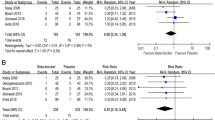

Pooling of the LVEF was available in six trials comprising 533 patients (average age, 48.1 years; female patients, 89%). The baseline LVEF between the carvedilol and placebo groups was not significantly different (64.0% vs 64.5%; P = 0.52). At the end of the follow-up (4–6 months), the pooling result revealed a statistically significant small difference between the two groups (MD, 3.47; 95% CI, 0.56–6.37; P = 0.02). The heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 86%) (Fig. 2).

The forest plot of the effect of carvedilol on LVEF post-chemotherapy a shows the pooling result of all the studies using carvedilol and b shows the pooling result of the studies after the exclusion of the N. K. study. Rezvanie Salehi-1 and Rezvanie Salehi-2 were two different experimental groups in the same study, receiving different dosage of carvedilol, 12.5 mg and 25 mg once daily

Sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome

The Galbraith plot revealed that the substantial heterogeneity came from the two studies by N. K. et al. [24] and M. N. et al. [27]. The exclusion of the study by N. K. et al. reduced I2 from 86 to 67% (MD, 1.74; 95% CI, − 0.18 to 3.66; P = 0.08). Excluding the study by M. N. et al., heterogeneity further decreased from 67 to 8% (MD, 0.51; 95% CI, − 0.47 to 1.09; P = 0.31). Then, with any single study excluded from among the rest, the pooling results remained similar and did not differ from the overall estimate (Online Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 in the Supplement).

Clinically overt cardiotoxicity and all-cause mortality

The aggregated results revealed that the incidence of clinically overt cardiotoxicity was lower in the carvedilol group than the placebo group (Peto OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.20–0.89; P = 0.02). In the study by Elitok [26], none of the patients developed overt cardiotoxicity in both groups. For the estimate of all-cause mortality, 10 deaths among 278 patients (3.6%) were reported in the carvedilol group and 11 deaths among 255 patients (4.3%) in the placebo group. The pooled estimate revealed no statistically significant difference in the two groups (Peto OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.36–2.23; P = 0.81). No case of death was reported in either group in two studies [26, 29] (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Change of the LV end-diastolic diameter

Pooling of LV end-diastolic diameter was available in three studies. Post-chemotherapy, the LV end-diastolic diameter increased in the placebo group compared with the carvedilol group (MD, − 1.41; 95% CI, − 2.32 to − 0.50; P = 0.002). No significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 31%) (Online Fig. 3 in the Supplement).

Diastolic dysfunction

We extracted the E/A ratio from five trials. The pooled results did not exhibit the statistical significance (MD, 0.03; 95% CI, − 0.03 to 0.09; P = 0.29). No significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 27%) (Online Fig. 4 in the Supplement).

Risk of bias in the included studies

Both summary and graph figures of the risk of bias were presented to reveal the proportion of studies with each of the judgments (“low risk,” “high risk,” and “unclear risk”) (Fig. 4). Among included studies, while four were conducted with appropriate randomization, others did not describe the methods for randomization, although words such as “randomly” and “randomized” were mentioned. Most articles did not report allocation concealment, except Pituskin [22], Gulati [23], and Avila [28], using central dispensation or sealed envelopes. We classified the three open-labeled studies as “high risk.” M. N. et al. could not follow some patients throughout the study, but the attrition in both groups seemed balanced (experimental group, four patients; control group, five patients). In the study by Avila, eight patients had no valid randomization, thus were excluded in the trial. N. K. et al. neither reported the standard deviation (SD) of the post-chemotherapy LVEF nor replied to our e-mail; thus, we could not eliminate the possibility of “high risk” for selective reporting. Finally, Egger’s test did not exhibit a significant published bias regarding the primary outcome (P = 0.127).

Discussion

We systematically reviewed ten prospective RCTs for four beta-blockers, carvedilol (six studies; 545 participants), nebivolol (one study; 45 participants), metoprolol (two studies; 146 participants), and bisoprolol (one study; 61 participants), and used meta-analysis to quantitatively assess, at least, three studies for the following outcomes: LVEF, LV end-diastolic diameter, E/A ratio, clinically overt cardiac dysfunction, and all-cause mortality. This review could update the information on the effects of the prophylactic use of carvedilol for cardioprotection in the setting of chemotherapy-mediated cardiotoxicity and help with a comprehensive therapy regimen design for cancer survivors.

Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity incorporates multiple cardiovascular manifestations and is mostly characterized by an asymptomatic decline in the LVEF [30]. Our initial outcome corroborated this and exhibited a considerable small LVEF decrease in the placebo group than the carvedilol group. Per the Galbraith plot, the substantial heterogeneity was primarily attributed to two studies, N. K. et al. and M. N. et al. By excluding the study by N. K. et al., the heterogeneity declined to 67%, but the outcome had been reversed (MD, 1.74; 95% CI, − 0.18 to 3.66; P = 0.08). Several things could be accountable for this discrepancy. First, patients in this study received relatively higher doses of anthracyclines and, thus, were supposed to exhibit a higher incidence of cardiotoxicity considering the dose-dependent feature of anthracycline [10]. And this could make the effect of using a cardioprotective agent more tangible. However, the contemporary chemotherapy protocol had been reformed, and the anthracycline dosage was much lower in the latest studies. Second, the SDs of the LVEF were not provided initially but extracted from another review [31], which could have affected the results. Third, the sample size was small (25 patients/group). The pooled result of the remaining studies demonstrated that carvedilol exerted no impact on the early asymptomatic LVEF reduction (MD, 1.74; 95% CI, − 0.18 to 3.66; P = 0.08; I2 = 67%). Regarding the heterogeneity from the study by M. N. et al., one possible reason could be that, opposed to most included trials, the average daily dose of carvedilol was much lower (6.7 vs 12.5 mg, q.d.). Although the LVEF was similar at the baseline in the two groups in this study, troponin I was considerably higher in the control group than the carvedilol group, suggesting that the control group could have more impaired myocardium than the carvedilol group at the baseline. To the best of our knowledge, the study by Avila [28] was the latest RCT on this subject with the largest sample size and the most credible results thus far. And our results were more in agreement with this study. In the trial by Elitok [26], although the LVEF remained unchanged in both groups, carvedilol did exhibit a protective effect by preventing the decrease in LV strains, as strain imaging is more sensitive than the LVEF when detecting the subclinical cardiac damage [32].

Our pooled results revealed a lower incidence of overt cardiotoxicity in patients receiving carvedilol than those receiving placebo, strengthening the conclusion that carvedilol could help prevent the deterioration of the cardiac function when previous studies only reported the numerical difference. Admittedly, different cutoff values were adopted among the included studies, but considering that the clinical endpoints of chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity remained debatable and the patient population is highly heterogeneous in the practical oncological setting, a safe conclusion could be that the prophylactic use of carvedilol could decrease the incidence of overt cardiac dysfunction in patients with cancer. However, the ultimate effect awaits confirmation by extensive, well-designed clinical trials.

Our analysis did not observe a statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the 6-month all-cause mortality. Conversely, another meta-analysis [33], which pooled data from five RCTs with 317 patients, reported that beta-blockers correlated with the reduction of all-cause mortality (Peto OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.12–0.92; P = 0.03) in patients undergoing chemotherapy. However, as the full text of this meta-analysis was unavailable, more detailed documents would be needed to ascertain whether this discrepancy arose because of the types of beta-blockers or the included population. As these studies did not offer specific reasons for deaths, cardiovascular mortality could not be separately assessed in both our reviews.

Pooling LV end-diastolic diameters revealed that carvedilol use could inhibit the enlargement of the LV chamber, suggesting that carvedilol could affect LV remodeling in this setting. The PRADA trial [34] tested whether candesartan and/or metoprolol could prevent anthracycline therapy–associated interstitial fibrosis by T1 mapping and ECV, which was proved to correlate favorably with myocardial biopsy measurements [35].

Regarding the diastolic function, the study by Avila reported a lower incidence of diastolic dysfunction in the carvedilol group than the placebo group (37.2% vs 28.5%; P = 0.039). In fact, most studies reported that the E/A ratio reflects the diastolic function in patients. Our aggregated outcome of the E/A ratio did not exhibit a statistical difference in the two groups.

Pooling of the results was impossible for the other three beta-blockers (nebivolol, metoprolol, and bisoprolol) because of the insufficient number of studies. The study by Kaya et al. [36] using nebivolol and that by Pituskin [22] using bisoprolol reported a cardioprotective effect, but not for the two studies using metoprolol [23, 37]; results were summarized in Table 3. The power of the evidence was considered relatively low either because of the small sample sizes or because of inadequate reporting. The results about the effect of metoprolol were consistent in the two studies; both invalidated the use of metoprolol in this scenario. An earlier meta-analysis [38], which pooled results of the three different beta-blockers (nebivolol, metoprolol, and bisoprolol), reported an insignificant difference in the LVEF change (WMD, 3.05; 95% CI, − 7.22 to 1.12; P = 0.15) between groups, but a lower heart failure incidence (OR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.14–0.80; P = 0.01) in the beta-blocker group, which was to some extent consistent with our outcomes.

Limitations and potential biases in the review process

First, only adult patients were included in this review. We excluded young patients in this study because of some differences between adult and pediatric patients. However, admittedly, childhood cancer survivors are another large group affected by chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity, which we intend to address in a future study. Second, our conclusions remained generalized to the long-term setting, as the follow-up duration of all the included trials ended at 4–6 months. Finally, only the effects of carvedilol were quantitatively assessed. Hence, further clinical trials are warranted for the estimation of other beta-blockers such as nebivolol, bisoprolol, and metoprolol.

Conclusions

The prophylactic use of carvedilol exerts no impact on the early asymptomatic LVEF decrease but seemingly attenuates the frequency of clinically overt cardiotoxicity and prevents ventricular remodeling. Nevertheless, prolonged and extensive studies are warranted to validate the efficacy of carvedilol.

References

Lamm DL (2010) Cancer statistics. Ca A Cancer J Clin 40(5):318–319

Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, Wasilewski K, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Yasui Y (2008) Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(19):1368–1379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn310

Du XL, Fox EE, Lai D (2008) Competing causes of death for women with breast cancer and change over time from 1975 to 2003. Am J Clin Oncol 31:105–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0b013e318142c865

Lefrak EA, Pitha J, Rosenheim S, Gottlieb JA (1973) A clinicopathologic analysis of adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Cancer 32:302–314

Vazluis I, Keating NL, Lin NU, Lii H, Winer EP, Freedman RA (2014) Duration and toxicity of adjuvant trastuzumab in older patients with early-stage breast cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 32:927–934. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1261

Chen J, Long J, Steingart R, Gross CP (2012) Incidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy after adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol 60(24):2504–2512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.068

Bovelli D, Plataniotis G, Roila F, Group EGW (2010) Cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy-related heart disease: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol 21(Suppl 5):v277. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq200

Patnaik JL, Byers T, Diguiseppi C, Dabelea D, Denberg TD (2011) Cardiovascular disease competes with breast cancer as the leading cause of death for older females diagnosed with breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res 13(3):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2901.

Shenoy C, Klem I, Crowley AL, Patel MR, Winchester MA, Owusu C, Kimmick GG (2011) Cardiovascular complications of breast cancer therapy in older adults. Oncologist 16(8):1138–1143. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0348

Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS (2003) Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer 97(11):2869–2879. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11407

Ky B, Vejpongsa P, Yeh ET, Force T, Moslehi JJ (2013) Emerging paradigms in cardiomyopathies associated with cancer therapies. Circ Res 113(6):754–764. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300218

Dalen EV, Michiels EM (2006) Different anthracycline derivates for reducing cardiotoxicity in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6(3):CD005006. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005006.pub4.

Spallarossa P, Garibaldi S, Altieri P, Fabbi P, Manca V, Nasti S, Rossettin P, Ghigliotti G, Ballestrero A, Patrone F (2004) Carvedilol prevents doxorubicin-induced free radical release and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes in vitro. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37(4):837–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.024

Santos DL, Moreno AJ, Leino RL, Froberg MK, Wallace KB (2002) Carvedilol protects against doxorubicin-induced mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 185(3):218–227

Rehsia NS, Dhalla NS (2010) Mechanisms of the beneficial effects of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists in congestive heart failure. Exp Clin Cardiol 15(4):e86–e95

Feuerstein G, Yue TL, Ma X, Ruffolo RR (1998) Novel mechanisms in the treatment of heart failure: inhibition of oxygen radicals and apoptosis by carvedilol. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 41(1 Suppl 1):17–24

Dandona P, Ghanim H, Brooks DP (2007) Antioxidant activity of carvedilol in cardiovascular disease. J Hypertens 25(4):731–741. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280127948

Jonsson O, Behnam-Motlagh P, Persson M, Henriksson R, Grankvist K (1999) Increase in doxorubicin cytotoxicity by carvedilol inhibition of P-glycoprotein activity. Biochem Pharmacol 58(11):1801–1806

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC, Cochrane Bias Methods Group, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group (2011) The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343:d5928–d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0

Pituskin E, Mackey JR, Koshman S, Jassal D, Pitz M, Haykowsky MJ, Pagano JJ, Chow K, Thompson RB, Vos LJ, Ghosh S, Oudit GY, Ezekowitz JA, Paterson DI (2017) Multidisciplinary approach to novel therapies in cardio-oncology research (MANTICORE 101–breast): a randomized trial for the prevention of Trastuzumab-associated cardiotoxicity. J Clin Oncol 35:870–877. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.7830

Gulati G, Heck SL, Ree AH, Hoffmann P, Schulz-Menger J, Fagerland MW, Gravdehaug B, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bratland Å, Storås TH, Hagve TA, Røsjø H, Steine K, Geisler J, Omland T (2016) Prevention of cardiac dysfunction during adjuvant breast cancer therapy (PRADA): a 2 × 2 factorial, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of candesartan and metoprolol. Eur Heart J 37:1671–1680. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw022

Kalay N, Basar E, Ozdogru I, Er O, Cetinkaya Y, Dogan A, Oguzhan A, Eryol NK, Topsakal R, Ergin A, Inanc T (2006) Protective effects of carvedilol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:2258–2262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.052

Jhorawat R, Kumari S, Varma SC, Rohit MK, Narula N, Suri V, Malhotra P, Jain S (2016) Preventive role of carvedilol in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy. Indian J Med Res 144(5):725

Elitok A, Oz F, Cizgici AY, Kilic L, Ciftci R, Sen F, Bugra Z, Mercanoglu F, Oncul A, Oflaz H (2014) Effect of carvedilol on silent anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity assessed by strain imaging: a prospective randomized controlled study with six-month follow-up. Cardiol J 21:509–515. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2013.0150

Nabati M, Janbabai G, Baghyari S, Esmaili M, Yazdani J (2017) Cardioprotective effects of carvedilol in inhibiting doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 69(5):279–285. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000000470

Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, de Barros Wanderley Junior MR et al (2018) Carvedilol for prevention of chemotherapy related cardiotoxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol 71:2281–2290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.049

Salehi R, Zamani B, Esfehani A et al (2011) Protective effect of carvedilol in cardiomyopathy caused by anthracyclines in patients suffering from breast cancer and lymphoma. Am Heart Hosp J 9:95. https://doi.org/10.15420/ahhj.2011.9.2.95

Colombo A, Cipolla C, Beggiato M, Cardinale D (2013) Cardiac toxicity of anticancer agents. Curr Cardiol Rep 15(5):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-013-0362-6.

Yun S, Vincelette ND, Abraham I (2015) Cardioprotective role of β-blockers and angiotensin antagonists in early-onset anthracyclines-induced cardiotoxicity in adult patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J 91:627–633. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133535

Negishi K, Negishi T, Hare JL, Haluska BA, Plana JC, Marwick TH (2013) Independent and incremental value of deformation indices for prediction of trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26:493–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2013.02.008

Manrique CR, Spinetto PV, Tiwari N, Romero J, Jorde U, Garcia M (2016) Protective effect of beta-blockers on chemotherapy induced cardiomyopathy: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 67:1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(16)31530-3

Heck SL, Gulati G, Hoffmann P, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Storås TH, Ree AH, Gravdehaug B, Røsjø H, Steine K, Geisler J, Schulz-Menger J, Omland T (2017) Effect of candesartan and metoprolol on myocardial tissue composition during anthracycline treatment: the PRADA trial. Eur Heart J - Cardiovasc Imaging 19:544–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jex159

Diao K, Yang Z, Xu H, Liu X, Zhang Q, Shi K, Jiang L, Xie LJ, Wen LY, Guo YK (2017) Histologic validation of myocardial fibrosis measured by T1 mapping: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-016-0313-7.

Kaya MG, Ozkan M, Gunebakmaz O, Akkaya H, Kaya EG, Akpek M, Kalay N, Dikilitas M, Yarlioglues M, Karaca H, Berk V, Ardic I, Ergin A, Lam YY (2013) Protective effects of nebivolol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: a randomized control study. Int J Cardiol 167:2306–2310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.023

Georgakopoulos P, Roussou P, Matsakas E, Karavidas A, Anagnostopoulos N, Marinakis T, Galanopoulos A, Georgiakodis F, Zimeras S, Kyriakidis M, Ahimastos A (2010) Cardioprotective effect of metoprolol and enalapril in doxorubicin-treated lymphoma patients: a prospective, parallel-group, randomized, controlled study with 36-month follow-up. Am J Hematol 85:894–896. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21840

Gujral DM, Lloyd G, Bhattacharyya S (2018) Effect of prophylactic betablocker or ACE inhibitor on cardiac dysfunction & heart failure during anthracycline chemotherapy ± trastuzumab. Breast 37:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2017.10.010

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471721, 81471722, 81771887, and 81771897), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-13-0386), and Program for Young Scholars and Innovative Research Team in Sichuan Province (2017TD0005) of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Additional information

Shan Huang and Qin Zhao are co-first authors.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 286 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, S., Zhao, Q., Yang, Zg. et al. Protective role of beta-blockers in chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity—a systematic review and meta-analysis of carvedilol. Heart Fail Rev 24, 325–333 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-018-9755-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-018-9755-3