Abstract

Academic freedom is under threat across the globe and a wave of substantial academic freedom declines affects not only autocracies but also (liberal) democracies. However, although the development of academic freedom has generated scholarly attention, this article presents the first systematic conceptualization and measurement of academic freedom growth and decline episodes. In particular, this article systematically analyzes the development of academic freedom across the globe and shows that global development follows waves of growth and decline. The first growth wave started in the mid-1940s and was succeeded by a second growth wave that started around 1977 and lasted for more than 30 years resulting in the greatest improvement in academic freedom that has been recorded since 1900. However, since 2013, we see an ongoing decline wave in academic freedom. Overall, this article highlights how academic freedom developed over time and across the globe in waves of growth and decline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decline of academic freedom in recent years has emerged as a pressing global challenge. Declines in academic freedom in countries as diverse as Russia, Brazil, Hong Kong, Poland, Hungary, and the USA, among others have not been analyzed as interrelated global developments. Relevant studies focus on individual countries (e.g., Enyedi, 2018; Kaczmarska, 2020; Taylor et al., 2022) or use a small and medium-n comparative approach (e.g., Matei, 2020; Ramanujam & Wijenayake, 2022). Thus, a comprehensive analysis of global trends in academic freedom developments is missing in the literature so far. However, newly introduced data on academic freedom (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022) enables the global and temporal analysis of trends in academic freedom. This article uses this time-series global data to substantiate the argument that academic freedom has evolved in waves of growth and decline.

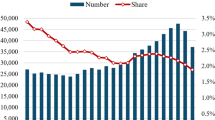

As a first step, this article develops a systematic conceptualization and measurement of academic freedom growth and decline episodes to analyze the global development of academic freedom since 1990. However, until now these processes of decline and growth in academic freedom have not been conceptualized as episodes of (gradual) change in the respective countries. The evidence presented in Fig. 1 supports the claim that academic freedom evolved in waves of growth and reverse waves of decline in academic freedom quality. By using the wave metaphor to describe the development of academic freedom globally, this article uses a popular explanation from political science to “describe major trends in global regime changes in the direction to or from democracy” (Skaaning, 2020, p. 1533). Huntington (1993) popularized the waves-metaphor arguing that democratization has occurred in three waves. He defines a democratic wave as “a group of transitions from nondemocratic to democratic regimes that occur within a specified period of time and that significantly outnumber transitions in the opposite directions during that period of time” (Huntington, 1993, p. 15).Footnote 1 Lührmann and Lindberg re-adopted the waves-metaphor to the study of autocratization defined as democratization in reverse that “can occur both in democracies and autocracies” (Lührmann & Lindberg, 2019, p. 1089). In this article, waves of academic freedom growth and decline are not mutually exclusive and can overlap (cf. Skaaning, 2020). I argue that the waves-metaphor can also describe academic freedom growth and declines across the globe.

Figure 1A reveals that global development in academic freedom indeed emerged in waves of growth and decline. In addition, Fig. 1B shows the global average of the Academic Freedom Index to compare the waves in academic freedom development with the average academic freedom in the world. The first wave of academic freedom declines emerged in the 1930s to 1940s and was succeeded by a first major growth wave beginning in the mid-1940s after WWII. Accompanied by the so-called third wave of democratization, a wave of academic freedom growth emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s (see Fig. 1)Footnote 2 and has led to the greatest increase in academic freedom that has been recorded. This growth wave in academic freedom was superseded by a third decline wave around 2010 that is ongoing.

This article contributes to the literature in three distinct ways. First, it provides a definition of an academic freedom growth episode as substantial de facto increases of core components of academic freedom in individual countries. Consequently, an academic freedom decline episode is defined as substantial de facto drops of core components of academic freedom. This definition of episodes as interrelated timelines in which academic freedom accumulates or declines is more encompassing than earlier approaches of comparing academic freedom between two different relatively arbitrarily chosen years to map declines and increases in academic freedom (e.g., Kinzelbach et al., 2022).

Our notion of academic freedom is based on the conceptualization of academic freedom as the de facto implementation of core components, namely freedom to research and teach, freedom of academic exchange and dissemination, institutional autonomy, campus integrity, and freedom of cultural and academic expression (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022).

Second, this article offers a systematic operationalization that captures the conceptual meaning of academic growth and decline as episodes of substantial change on data from the Academic Freedom Index (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022), curated in the Varieties of Democracy project (V-Dem). These two new measurements have multiple advantages compared to ad hoc conceptualizations of yearly comparisons: They are sensitive to changes in the de facto implementation of academic freedom; they are nuanced enough to also capture gradual processes of growth and decline and thus not only measure fast-moving changes; moreover, they provide researchers and users with definitive start and end dates of growth and decline episodes, and they provide information on how much academic freedom declined or increased in the respective episode.

Third, this article adds empirical evidence to the discussion on the development of academic freedom across the globe. This research shows that the global development of academic freedom follows waves of growth and decline. The main argument this article presents is that the major drivers of growth and decline episodes are political developments. By investigating whether democratization and autocratization and the development of academic freedom are associated over time and globally, this article focuses on political development rather than changing economic conditions for universities and higher education. The latter are in fact relevant determinants of academic freedom. While this study first describes the global development of academic freedom and then offers one of several possible explanatory models, the relationship between economic conditions and academic freedom needs to be investigated in further studies. Future research can test its hypotheses with the new data presented in this article.

However, even though the article and previous research show that academic freedom is under threat across the globe (e.g., Kinzelbach et al., 2022) and a third wave of academic freedom decline is ongoing globally, this article also emphasizes that the development of academic freedom was a success story. Using country-averages academic freedom peaked in 2006 at a value of 0.65 and decreased only slightly to 0.61 in 2021 on a scale between 0 (no academic freedom) and 1 (almost full academic freedom). However, when using the population-weighted averages, the picture looks different. The peak between 2003 and 2009 was followed by a more pronounced decline in the level of academic freedom from 0.6 to 0.42 in 2021, a level of academic freedom last registered four decades ago (Kinzelbach et al., 2022).

This article proceeds as follows. First, academic freedom is defined and the conceptualization and operationalization are presented. Next, this article presents a discussion of different strategies for conceptualizing and measuring growth and decline episodes in academic freedom. Then it proposes an empirical measurement of these growth and decline episodes. The article provides empirical evidence that academic freedom develops in waves of growth and decline. Lastly, this article discusses how academic freedom developments are associated with democratization and autocratization.

Defining and conceptualizing academic freedom

Any conceptualization of growth and decline episodes of academic freedom has to begin with a clear understanding of what academic freedom constitutes. Although there is no single and universal understanding of academic freedom (e.g., Altbach, 2001; Eisenberg, 1987; Fuchs, 1963; Marginson, 2014; Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022), the definition of academic freedom used by the Academic Freedom Index (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022) seems reasonable for the following reasons: (1) comparability across time and space; (2) universalistic definition based on international law; (3) multi-faced nature of the concept.

Before going into more detail regarding the definition of academic freedom and conceptualization of the Academic Freedom Index, I briefly summarize existing accounts. Fuchs (1963) and Eisenberg (1987) define academic freedom as the “freedom of members of the academic community, assembled in colleges and universities, which underlies the effective performance of their functions of teaching, learning, practice of the arts, and research” (Fuchs, 1963, p. 431). By doing so, both rest on the dominating US-American perspective on academic freedom as an individual freedom of faculty members (Eisenberg, 1987, p. 1364).

Besides this perspective on academic freedom, Altbach (2001) defines academic freedom by emphasizing institutional autonomy of the university. However, he also emphasizes academic freedom of professors (Altbach, 2001, p. 206). In addition, Marginson (2014, p. 24) argues that academic freedom varies “across the world, according to variations in political cultures, educational cultures and state-university relations.” Thus, in this sense, academic freedom is in fact not only a universal principle but also context-dependent.

The Academic Freedom Index (AFI) defines academic freedom “in favor of a universalistic angle based on international law that seeks to do justice to the multi-faceted nature of the concept” (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022, p. 5). As such, academic freedom is defined as the de facto realization of academic freedom dimensions, namely freedom to research and teach, the freedom of academic exchange and dissemination, the institutional autonomy of higher education institutions, campus integrity, and freedom of academic and cultural expression. These dimensions of academic freedom are well aligned with the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights comments (CESCR 2020) on article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966. In addition, conceptualizing academic freedom through five different dimensions allows for the disaggregation of the index to consider these dimensions separately. In sum, the academic freedom measure maps “all undue interference by non-academic actors as infringements on academic freedom” (Spannagel et al., 2020, p. 8).

In particular, the freedom to research and teach indicator asked to “what extent are scholars free to develop and pursue their own research and teaching agendas without interference.” The indicator on freedom of academic exchange and dissemination assesses the extent to which scholars are free to exchange and communicate research ideas and findings. The institutional autonomy indicator evaluates to what extent universities exercise institutional autonomy in practice. The campus integrity indicator asks how free campuses are from politically motivated surveillance or security infringements. Lastly, the freedom of academic and cultural expression indicator captures academics’ freedom of expression in relation to political issues.

After discussing the definition of academic freedom used in this article, I will briefly present the data collection process. Academic freedom is assessed at the country-year level meaning that variations between institutions and geographic regions within the same country as well as between different disciplines are not recorded.Footnote 3 The AFI is expert-coded data and rests on assessments by more than 2000 country-experts worldwide. These country-experts, who have diverse backgrounds and expertise, assess the different dimensions of academic freedom by answering standardized questionnaires. The AFI typically gathers data from more than five country experts per country-year observation.Footnote 4 To handle these coder-level assessments, V-Dem has developed a state-of-the-art method for aggregating expert judgments that produces valid and reliable estimates of difficult-to-observe concepts, such as academic freedom (Coppedge et al., 2020; Pemstein et al., 2023). In particular, V-Dem’s customized Bayesian item response theory (IRT) measurement model assumes that there are concepts that we cannot directly observe, like the level of academic freedom. Instead, we can only assess imperfect versions of these concepts in the form of the ratings that experts give. V-Dem’s IRT model takes these ratings and converts them into a single continuous latent scale.Footnote 5

However, the way experts rate academic freedom and its dimensions may differ between experts, cases, and time. The V-Dem customized IRT measurement model uses various techniques to increase between-country and over-time comparability (Coppedge et al., 2020; Pemstein et al., 2023). For example, the measurement model calculates how reliable each expert is in comparison to others, as well as how their rating scales may differ from those of other experts.Footnote 6 In addition, academic freedom is conceptualized unrelated to different conceptualization of academic freedom evolved during the twentieth and twenty-first century to increase over-time comparability. Overall, relying on a broad temporal and spatial sample reduces potential biases that may result from a short time frame or a small geographical coverage, or a combination of these two (McMann et al., 2022, p. 437). For detailed assessments of the data generation process and the data quality, a paper by Pelke and Spannagel (2023) may be instructive.

To aggregate the five questions into the Academic Freedom Index, the point estimates from a Bayesian factor analysis were taken using 900 draws randomly selected from the posterior distribution.Footnote 7

Defining episodes of academic freedom growth and decline

Building on this definition of academic freedom, this article follows Lührmann and Lindberg (2019) and subsequent publications on gradual regime change (Edgell et al., 2020; Maerz et al., 2023) and takes an episode approach to measure growth and decline episodes of academic freedom rather than modeling academic freedom change as a discrete outcome. Thus, we are able to identify whether academic freedom evolves and erodes gradually or in a fast-moving process of an annual drop or increase. In addition, the detection of the definitive start and end dates of such episodes enables scholars to analyze growth and decline episodes as a multi-stage process and enables the analysis of what determines the onset of such episodes.

To measure gradual growth and decline in academic freedom, we need nuanced cross-national time-series data with high quality on academic freedom. The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (Coppedge et al., 2023) and the Academic Freedom Index (AFI), in particular, offer a valuable source. The AFI data is sensitive to gradual and slow-moving change processes. Other data sources on academic freedom either compile a spatially limited sample of countries or a short time-series, or have ad hoc understandings of academic freedom (see also Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022). The Academic Freedom Index ranges on a continuous scale between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating greater academic freedom. The AFI data compiles country-year information for 180 countries from 1900 to the end of 2022, or 14,976 country-years.

This article defines a growth episode in academic freedom as a cumulative increase of 0.1 or more on the AFI, while it defines a decline episode in academic freedom as a cumulative drop of 0.1 or more (see also Pelke & Croissant, 2021, for a discussion on different thresholds). However, as the choice of any cutoff point on a continuous scale is relatively arbitrary, we also enable users to choose their own cutoff points by providing the replication data and an open-source software package in R. However, a change of 0.1 seems reasonable and is an intuitive choice to start with for the following reasons. A relatively demanding cutoff of 0.1 minimizes the risk of measurement error driving the results. However, when not considering measurement uncertainty in the measurement of episodes, the cutoff point needs to be more demanding to reduce the risks of measurement error. Therefore, our approach enables users to control for overlapping confidence intervals (before the start of an episode and at the end of an episode). Second, the “cut-off point should also be high enough to rule out inconsequential changes but low enough to capture substantial yet incremental changes” (Lührmann & Lindberg, 2019, p. 1101). This article uses the 0.1 cutoff point but does not control for overlapping confidence intervals. However, the Supplementary Appendix demonstrates the robustness of our main findings to higher cutoffs as well as the controls for overlapping confidence intervals.

Each growth and each decline episode have a start and an end date. To identify these start dates, this article defines the start of an episode as a yearly increase/decline of the AFI of 0.01 points or more. This article chooses this low threshold in order to identify the very beginning of any incremental episode. Second, it follows the potential episode as long as there is continued increase/decline, while allowing up to 4 years of temporary stagnation, meaning no further increase/decline of 0.01 points or more on the AFI. An episode ends when there is a temporary stagnation on the AFI with no further increase/decline of 0.01 points in 4 years or when the AFI increases by 0.03 points, from one year to the next (compare Lührmann & Lindberg, 2019, for a discussion on thresholds). To identify substantive growth and decline episodes, this article calculates the total magnitude of change from the year before the start of an episode to the end of an episode. This cumulative increase/drop is set to 0.1 (10% of the total 0–1 scale) and thus records only those manifest growth episodes which add up to a positive change of at least 0.1 and as manifest decline episodes only those which add up to a negative change of at least 0.1.

Diagnosing growth episodes

This article presents the first-ever comprehensive identification of the 246 episodes of growth in academic freedom taking place in 141 countries from 1900 to 2022 (Table A1 in the Supplementary Appendix), leaving only 39 countries unaffected. As shown in Fig. 1, growth episodes accumulated between 1940 and 1950 and around the fall of the iron curtain around 1990.

Figure 2 is a visualization of all growth and decline episodes on the Academic Freedom Index from 1900 to 2022. The top panel (Fig. 2A) illustrates the trajectories of country-episodes, in which academic freedom has declined (purple lines). Figure 2B show those country-episodes, in which academic freedom has grown (yellow lines). The length of the colored lines indicates how long a growth (decline) episode has been. As presented in Fig. 2C, the number of countries with data for academic freedom increases from 61 countries in 1900 to 179 countries in 2022.Footnote 8 In addition, growth episodes are also present in the last 10 years with more than seven growth countries per year.

As one can depict in Fig. 2, growth episodes (yellow lines) follow a relatively steep curve. Once they began, on average growth episodes lasted only 4.5 years (std.dev = 3.63; min = 1; max = 22). While growth episodes in 31 cases lasted 1 year (e.g., Egypt in 2011, Thailand in 1993, and Uganda in 1980), the growth episodes in the following cases all lasted more than 15 years: Egypt from 1971 to 1989, South Korea from 1980 to 1999, Moldova from 1991 to 2011, Taiwan from 1980 to 2000, and Cyprus from 1974 to 1995. On average, growth episodes led to an increase of 0.303 points with a standard deviation of 0.212. The cases with the smallest improvement are Republic of Congo with an increase of 0.1 (from 2020 to 2022, but censored), Georgia with 0.1 (in 2013), and Togo with 0.1 (in 1970). Uruguay from 1980 to 1990 shows the best improvement with an increase of 0.919, followed by Mongolia from 1987 to 1992 (0.892), Czechoslovakia from 1987 to 1990 (0.887), and Chile from 1990 to 1994 (0.881).

However, the frequency of growth and decline episodes of academic freedom should not be confounded with the intensity of a decline or growth episode. In Fig. 3, this article presents six countries (three with the best improvement, and three with the longest episodes) with growth episodes of academic freedom starting at different levels of academic freedom and resulting in different levels. For example, Uruguay shows an improvement in its academic freedom level within ten interrelated years that is not comparable to the improvements in academic freedom in Egypt between 1971 and 1989 resulting in an increase of 0.186. In sum, academic freedom growth and decline episodes are instructive indicators to identify coherent episodes of academic freedom change. However, these episodes result in different levels of academic freedom, which is a matter of degree.Footnote 9

In addition, Figs. 1 and 2 reveal that growth episodes have occurred in waves. The first wave of academic freedom growth started in the mid-1940s with the end of WWII. The first country with an onset of substantial improvement was Italy in 1943, followed by the Philippines (onset 1943), France (1944), Guatemala (1944), Ecuador (1944), and Uruguay (1944). In 1945, in 15 more countries an onset of a growth episode occurred, mostly in countries in Europe (Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Luxembourg, Norway, Serbia) and Asia (South Korea, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Taiwan). The second wave of academic freedom growth started around 1977 (the number of increasers clearly outnumbers the number of countries with decline episodes). This wave lasted more than 30 years until around 2004. Around 2004, the number of growth episodes and the number of decline episodes accompanied each other while after 2013 the number of decliners clearly outnumbers the number of growth episodes. However, the second wave of academic freedom growth resulted in the greatest improvement in academic freedom that has been documented since 1900 (see Fig. 4).

This finding may contradict the common assumption of the higher education literature that New Public Management (NPM) measures introduced after the 1980s (compare Marginson, 1997; Marginson & Considine, 2000) are negatively associated with academic freedom (e.g., Craig et al., 2014; Hedgecoe, 2016; Lorenz, 2012; Marginson & Considine, 2000). One common assumption may be that “the NPM generally and specific NPM techniques are on their face incompatible with academic freedom as a whole” (Marginson, 2008, p. 271). However, the empirical evidence supporting this assumption is hitherto only limited (Hedgecoe, 2016, p. 487) and the relevant literature largely relies on “hypotheticals” (e.g., Craig et al., 2014). However, this study’s findings do not necessarily contradict this reasoning, as the growth episodes in the 1980s and 1990s are globally distributed. The positive development in academic freedom worldwide resulting from the second growth wave may obscure the negative association between NPM and academic freedom in individual countries that are in particular affected by NPM measures in the 1980s and afterwards. In addition, this study argues that the major driver of these growth episodes is political development, as will be shown later. In sum, the association between NPM and academic freedom requires more empirical evidence, which is now possible with the new Academic Freedom Index data. However, this requires a different study design.

Diagnosing decline episodes

Figures 1 and 2 not only show the improvements in academic freedom in the last 120 years but also present evidence that substantial decline episodes can be depicted. In sum, this article identifies 176 of these between 1990 and 2022 taking place in 103 countries (Table A2 in the Supplementary Appendix), leaving 77 countries unaffected. As presented in Fig. 1, decline episodes accumulated between 1930 and 1944, 1965 and 1969, and after 2003 (until today).

The first decline wave started around 1930 with a gradual decline in the Weimar Republic resulting in an AFI of 0.053 in 1934 after the coming into power of the Nazis. In addition to the decline in the Weimar Republic, academic freedom started to also decline in Argentina in 1930, and the Dominican Republic. This reverse wave intensified in the middle of the 1930s with onsets in Czechoslovakia, Spain under Franco, Latvia, Estonia, Greece, Romania, and Paraguay. With the onset of WWII in Europe, academic freedom was in retreat, in particular in those countries under the occupation by the Third Reich or its allies. As shown above, this first reverse wave overlaps with the first growth wave. In the mid-decade of the 2000s, a third reverse wave unrolls leading to the highest number of countries in a decline episode that has ever been recorded. After 2003, academic freedom has substantially declined in 48 countries resulting in a population-averaged worldwide academic freedom index that has been last recorded at the beginning of the second growth wave (Kinzelbach et al., 2022).

As one can depict in Fig. 2, decline episodes (violet lines) follow a flatter slope compared to growth episodes. These episodes on average lasted 4.65 years (std.dev = 3.89; min = 1; max = 25). While decline episodes in 22 cases lasted 1 year (e.g., Argentina in 1967, France in 1914, and Cuba in 1952), the decline episodes in the following cases all lasted more than 15 years: Venezuela from 1998 to 2022, Hong Kong from 2000 to 2022, Russia from 2008 to 2022, Belarus from 1995 to 2010, and Romania from 1935 to 1950. Despite the decline episode in Romania, all these gradual decline episodes accumulated in the latest reverse wave.

Spain from 1934 to 1940 under Franco and Uruguay between 1963 and 1974 show the greatest decline with drops of 0.827 and 0.825, followed by Czechoslovakia from 1934 to 1940 (0.797), Norway from 1939 to 1944 (0.741), and Venezuela from 1998 to 2022 (0.688).

What is new in the third reverse wave is the gradual moves away from academic freedom. On average, a decline episode lasts 5.8 years (see also Fig. 2) and affects democracies more often.Footnote 10 For the decline episodes that had started before 2003, the average duration of an episode is 4.2 years.

Next, this article dives deeper into six selected countries with a decline episode in this third reverse wave. Figure 5 shows the development of academic freedom including recent decline episodes in the USA, Russia, Hong Kong, Brazil, India, and Hungary. For the USA, Fig. 5 indicates a decline episode that started in 2019, is ongoing in 2022 (right-censored), and results in a drop of 0.124 points to an AFI of 0.79 (compare Bérubé & Ruth, 2022). The decline episode that started in 2008 in Russia is one of the longest episodes of decline registered so far and is ongoing (right-censored). Overall, the decline episode in Russia results in a drop of 0.45 points in academic freedom over 15 years, resulting in an environment that does not enable free research and teaching (see also Kaczmarska, 2020) and an AFI of 0.24 in 2022.

Hong Kong is another example of a gradual process in academic freedom decline. Starting also in 1999, Hong Kong lost 0.663 points (equal to 75% of its AFI value in 1999) over 24 years resulting in an AFI of 0.23. As for the decline episode in Russia, the decline in academic freedom started out gradual and slow-moving and has accumulated in a sharper decline that has been started in 2009 (see also Carrico, 2018). In contrast, the decline episode that started in 2013 in Brazil was faster and led to a decline in academic freedom of 0.534 points equals a loss of 56% of its AFI from 2013. Today the AFI score is at 0.45. As described by Mendes (2020), government measures to decrease the institutional autonomy of universities, and constant discursive attacks by parts of society have created a hostile environment for free research. The decline in academic freedom also affects some of the most populous countries in the world. India’s academic freedom decline started in 2012 under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and became even worse under Narendra Modi since 2014.

Overall, India lost 0.333 points on the AFI resulting in an AFI of 0.38 in 2022. The first decline episode was interrupted by a short growth in academic freedom in 2020 before the decline continued in 2021, as shown in Fig. 5. Hungary, a member of the European Union, is another case of a gradual decline in academic freedom. Hungary is one of the cases that started with a well-implemented de facto academic freedom in 2009 with the term of prime minister Viktor Orbán. Orbán has restricted academic freedom systematically during his term which also resulted in the closing of the Central European University in Budapest in 2019 as a result of severe infringement of academic freedom principles (see also Enyedi, 2018). Overall, as shown by the six short case narratives shown in Fig. 5, the episode approach presented in this article is able to detect the definitive start and end dates of academic freedom decline and growth episodes that fit the description of case studies and coincide with our case knowledge. Overall, these case descriptions support the face validity of the presented measures.

As additional evidence for the relationship between decline episodes in academic freedom and democracy and autocracy, Table 1 shows the number of decline episodes that started in democracies and autocracies across the three waves as shown in Fig. 4. It indicates that in the first waves of academic freedom declines, 59% of decline episodes in academic freedom started in a democratic regime, while in the second reverse wave, only 14% of decline episodes started in a democracy. The third reverse wave once again stands out for its higher number of democracies in which a decline episode in academic freedom started. However, Table 1 diagnoses only 106 out of 176 decline episodes between 1900 and 2022. Nevertheless, the recent decline wave affects a high number of democracies that is comparable to the first wave of academic freedom declines. However, this descriptive evidence shown in Table 1 does not disentangle the more complex association between regime type and academic freedom.

Academic freedom growth and decline episodes and political regime transformations

This section presents the findings of a global analysis of the association between change episodes in the level of democracy and academic freedom. Previous research on the relationship between academic freedom and democracy has recently made important progress with new studies suggesting that democracy and academic freedom are strongly associated (e.g., Berggren & Bjørnskov, 2022; Bryden & Mittenzwei, 2013; Cole, 2017; Dahlum & Wig, 2021; Kratou & Laakso, 2022). In particular, Kratou and Laakso (2022) investigate the impact of academic freedom on electoral democracy in Africa using dynamic panel models. They find a positive impact of past experiences of academic freedom on the quality of elections. Berggren and Bjørnskov find that “moving to electoral democracy is positive, as is moving to electoral autocracy from other autocratic systems” (Berggren & Bjørnskov, 2022, p. 205) for academic freedom development stressing the importance of elections. In addition, they argue that there is a complex relationship between the political sphere and academic freedom, which is investigated by this article.

In a first step, this article tests the association of democratization and autocratization episodes and the level of academic freedom with a difference-in-differences design that exploits within-state variation. In a second step, this article reverses the link and tests whether academic freedom growth and decline episodes are associated with the level of democracy. By doing so, this article shows that both, democracy and academic freedom, are strongly associated.

Academic freedom is defined as presented above.Footnote 11 Democracy is defined as the electoral conception of democracy (Coppedge et al., 2020) and measured with the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI) from the V-Dem dataset (Coppedge et al., 2023). Based on the Electoral Democracy Index, this article uses fine-grained data for identifying democratization and autocratization from the Episodes of Regime Transformation dataset (Edgell et al., 2020). By using this conceptualization of democratization and autocratization, this article can detect those gradual improvements/declines in the level of democracy which lead to substantial change that should affect academic freedom. Supplementary Appendix F2 presents the democracy measure as well as the democratization and autocratization measure in more detail. By investigating whether democratization and autocratization and academic freedom are associated over time and globally, this article presents strong evidence that political developments are strongly related to the development of academic freedom.

Democratization is linked to more academic freedom

This first step investigates whether democratization and autocratization are systematically associated with academic freedom changes. I use the DiD estimator proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (De Chaisemartin & d’Haultfoeuille, 2020), which eliminates time-invariant differences between countries and allows for treatment switching (countries can move in and out of treatment) and can model time-varying, heterogeneous treatment effects. Figure 7 presents the average treatment effect and reveals that democratization is associated with an increase in the level of academic freedom by 0.033 (95% CI = [0.025; 0.041]) in the year of the treatment. This effect accumulates to a positive effect of 0.179 (95% CI = [0.136; 0.215]) 10 years after the treatment onset.

In addition, the pre-treatment estimators indicate that the treatment histories for the treated and the non-treated are comparable; and thus, the parallel trends assumption seems to hold. Overall, the findings presented in Fig. 7 support the notion that democratization increases the level of academic freedom. In addition, in Supplementary Appendix F4, I show that the positive effect holds when controlling for a series of covariates, including GDP per capita, population size, and judicial and legislative constraints on the executive.

Figure 9 shows the negative effect of autocratization on the level of academic freedom. It presents the average treatment effect on the treated and reveals that autocratization (or the onset of an episode respectively) causes a decline in the level of academic freedom by 0.043 (95% CI = [–0.054; –0.032]) in the year of the treatment. This effect accumulates to a negative effect of 0.24 (95% CI = [–0.351; –0.128]) 10 years after the treatment. Supplementary Appendix F5 supports this finding when testing for additional covariates.

Reverse test: academic freedom effects on democracy

In a reverse test of the relationship, this article estimates the statistical association between academic freedom growth and decline episodes and the respective level of democracy. Using the same DiD estimator as before, Fig. 8 indicates that the onset of an academic freedom growth episode is associated with an increase in the level of electoral democracy by 0.03 (95% CI = [0.021; 0.038]) in the year of the treatment. This effect accumulates to a positive effect of 0.296 (95% CI = [0.162; 0.429]) on electoral democracy 10 years after the treatment onset.

The parallel trends assumption holds in Fig. 8 as shown by the non-substantial effects before the treatment started. In contrast, the additional analyses presented in Supplementary Appendix F5 question the findings presented here. Controlling for covariates reveals that the onset of an academic freedom growth episode is not statistically associated with a change in the level of democracy. This supports the findings from Fig. 6 indicating that democratization is associated with a growth in academic freedom.

Figure 9 shows the negative effect of an academic freedom decline episode on electoral democracy. It presents the ATE and reveals that academic freedom decline is associated with a decline in the level of electoral democracy by 0.045 (95% CI = [–0.056; –0.034]) in the year of the treatment. This effect accumulates to a negative effect of 0.203 (95% CI = [–0.345; –0.061]) 10 years after the treatment. Additional robustness tests in Supplementary Appendix F5 support this finding.

By triangulating from the empirical evidence presented in Figs. 6, 7, 8, and 9, this article concludes that democratization is associated with academic freedom growth. The findings show that 10 years after a democratization episode started, academic freedom is 18% higher than at the year of the onset of a democratization episode, on average. Overall, the findings presented here and in the Supplementary Appendix provide important empirical evidence that (electoral) democracy and academic freedom are strongly associated while the test of the causal mechanisms between the two requires more sophisticated research designs.

Conclusion

This article presents the first systematic conceptualization and measurement of academic freedom growth and decline episodes from a historical perspective. In addition, it presents the development of academic freedom across the world since the 1900 and introduces a new methodFootnote 12 to identify gradual improvements and declines in academic freedom that may evolve gradually. This operationalization of academic freedom developments pinpoints the start and end dates of gradual improvements and decline episodes, which also enables studies on the systematic determinants of academic freedom declines and improvements and facilitates also sequential analysis. This article thereby contributes to recent discussions on the state of academic freedom (e.g., Bérubé & Ruth, 2022; Kinzelbach et al., 2022, to name a few).

Second, this article provides empirical evidence that academic freedom develops globally in waves of growth and decline. It depicts two major growth episodes in academic freedom globally, one of which started after the end of WWII and lasted until the mid-1950s, another started in 1977, had a peak in 1990 and 1991, and accompanied the so-called third wave of democratization. The positive global development of academic freedom in the second global growth wave may challenge the assumption that New Public Management (NPM) measures introduced after the 1980s (compare Marginson, 1997; Marginson & Considine, 2000) are negatively associated with academic freedom. Another key finding is that—starting in 2013—a global wave of academic freedom decline is ongoing (Kinzelbach et al., 2022). These decline episodes in academic freedom do not only affect autocracies and young democracies, but unlike prior waves also liberal democracies, e.g., the USA and Great Britain, are backsliding in their academic freedom protection.

Additionally, this article contributes to the debate on how and why democracy is associated with academic freedom (e.g., Cole, 2017; Dahlum & Wig, 2021; Enyedi, 2018; Kratou & Laakso, 2022; Pelke, 2023) by providing compelling evidence for a democratic dividend on academic freedom, including a large sample of countries between 1900 and 2022. However, future research can also test the connection between changing political and economic conditions for universities and higher education by using the AFI data. This article’s argument states that political regime developments are one of many key drivers of academic freedom development. Additionally, future research could help to reveal which components of democracy are especially relevant for the development of academic freedom. In other words: Does the introduction of clean and fair elections foster the development of academic freedom or is the liberal component of democracy a prerequisite for academic freedom growth? In sum, one conclusion is relatively clear: where democracy is in retreat, academic freedom is also in severe threat.

Data Availability

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XLVABM. The academic freedom growth and declines dataset, and the R package named EpisodeR are available here: https://github.com/LarsLott/EpisodeR.

Notes

In Figure A4 in the Supplementary Appendix, democratization and autocratization waves are plotted along with the growth and decline episodes in academic freedom.

Experts are asked to generalize in their assessment across universities and across disciplines for a given country. Spannagel and Kinzelbach argue that they “are aiming to assess the integrity of the academic community as a whole, and consider it to be dangerous to excuse or relativize the infringements on some subjects by the freedom of others – precisely because the targeting of a few sensitive subject areas is a known pattern of repression, and often spreads a culture of fear throughout the academic community. What is more, infringements on institutional autonomy affect all academics, regardless of their discipline” (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022, p. 9). However, they also acknowledge that “the quality of restrictions on the academic sector as a whole is different depending on whether only some or all disciplines are targeted, which is why we didn’t choose to focus on only the worst-off subject areas.” (Spannagel & Kinzelbach, 2022, p. 9). Additionally, the scope of infringements across academic disciplines is incorporated in the response scale of the first two indicators.

In sum, typically more than five expert coders per indicator per country-year (true for 99.58% of country-years) rate academic freedom dimensions. Thus, a single respondent’s biases cannot drive the resulting estimates (McMann et al., 2022, p. 436).

For more information on V-Dem’s measurement model, see Pemstein et al. (2023).

It also uses overlapping coding (some experts code multiple countries) and all experts code hypothetical cases—so-called anchoring vignettes—to estimate the degree to which differences in scale perception are systematic across experts who code different sets of cases.

Please note that Academic Freedom Index data is only available for countries with at least one university in a given country-year.

The intensity of growth or decline of academic freedom is estimated by the R-package.

Definition of regime types according to the Regimes of the World data from V-Dem.

However, the academic freedom index used in this section excludes the freedom of academic and cultural expression (v2clacfree) indicator that comes from the Civil Liberty survey in the V-Dem dataset. The reason for excluding this indicator of original the academic freedom index stems from the fact that the v2clacfree indicator was also used to construct the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI) in the V-Dem dataset. By excluding the v2clacfree indicator from the AFI, this article avoids the pitfall of using the same components of a measure on both sides of the regression equation. More information can be found in Supplementary Appendix F1.

Previously used in comparative politics to disentangle political regime developments (democratization and autocratization).

References

Altbach, P. G. (2001). Academic freedom: International realities and challenges. Higher Education, 41(1–2), 205–219.

Berggren, N., & Bjørnskov, C. (2022). Political institutions and academic freedom: Evidence from across the world. Public Choice, 190(1), 205–228.

Berg-Schlosser, D. (2009). Long waves and conjunctures of democratization. In C. Haerpfer, R. Inglehart, C. Welzel & P. Bernhagen (Eds.) Democratization (1st ed., pp. 41–54). Oxford University Press

Bérubé, M., & Ruth, J. (2022). It’s not free speech: Race, democracy, and the future of academic freedom. John Hopkins University Press.

Bryden, J., & Mittenzwei, K. (2013). Academic freedom, democracy and the public policy process. Sociologia Ruralis, 53(3), 311–330.

Carrico, K. (2018). Academic freedom in Hong-Kong since 2015: Between two systems. Hong Kong Watch. Retrieved December 6, 2023, from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58ecfa82e3df284d3a13dd41/t/5a65b8ece4966ba24236ddd4/1516615925139/Academic+Freedom+report+%281%29.pdf

Cole, J. R. (2017). Academic freedom as an indicator of a liberal democracy. Globalizations, 14(6), 862–868.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Glynn, A., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., Skaaning, S.-E., Teorell, J., & Altman, D., et al. (2020). Varieties of democracy: Measuring two centuries of political change. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108347860

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Grahn, S., Hicken, A., Kinzelbach, K., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Mechkova, V., Neundorf, A., & Ziblatt, D. (2023). VDem [country-year/country-date] dataset v13. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds23

Craig, R., Amernic, J., & Tourish, D. (2014). Perverse audit culture and accountability of the modern public university. Financial Accountability & Management, 30(1), 1–24.

Dahlum, S., & Wig, T. (2021). Chaos on campus: Universities and mass political protest. Comparative Political Studies, 54(1), 3–32.

De Chaisemartin, C., & d’Haultfoeuille, X. (2020). Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Review, 110(9), 2964–2996.

Doorenspleet, R. (2000). Reassessing the three waves of democratization. World Politics, 52(3), 384–406.

Edgell, A. B., Maerz, S. F., Maxwell, L., Morgan, R., Medzihorsky, J., Wilson, M. C., Boese, V. A., Hellmeier, S., Lachapelle, J., Lindenfors, P., Lührmann, A., & Lindberg, S. I. (2020). Episodes of Regime Transformation Dataset (v1.0) Codebook. Retrieved May 29, 2020. https://github.com/vdeminstitute/ERT/releases/tag/V2.2. Accessed 6 Dec 2023

Eisenberg, R. S. (1987). Academic freedom and academic values in sponsored research. Tex. L. Rev., 66, 1363.

Enyedi, Z. (2018). Democratic backsliding and academic freedom in Hungary. Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), 1067–1074.

Fuchs, R. F. (1963). Academic freedom. Its basic philosophy, function, and history. Law and Contemporary Problems, 28(3), 431–446.

Hedgecoe, A. (2016). Reputational risk, academic freedom and research ethics review. Sociology, 50(3), 486–501.

Huntington, S. P. (1993). The third wave: Democratization in the late twentieth century (Vol. 4). University of Oklahoma Press.

Kaczmarska, K. (2020). Academic freedom in Russia. In K. Kinzelbach (Ed.), Researching academic freedom: Guidelines and sample case studies (pp. 103–140). FAU University Press.

Kinzelbach, K., Lindberg, S. I., Pelke, L., & Spannagel, J. (2022). Academic freedom index - 2022 update (tech. rep.). Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) and Varieties of Democracy Institute. https://doi.org/10.25593/opus4-fau-18612

Kratou, H., & Laakso, L. (2022). The impact of academic freedom on democracy in Africa. The Journal of Development Studies, 58(4), 809–826.

Kurzman, C. (1998). Waves of democratization. Studies in Comparative International Development, 33, 42–64.

Lorenz, C. (2012). If you’re so smart, why are you under surveillance? Universities, neoliberalism, and new public management. Critical Inquiry, 38(3), 599–629.

Lührmann, A., & Lindberg, S. I. (2019). A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization, 26(7), 1095–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

Maerz, S. F., Edgell, A. B., Wilson, M. C., Hellmeier, S., & Lindberg, S. I. (2023). Episodes of regime transformation. Journal of Peace Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433231168192

Marginson, S. (2008). Academic creativity under new public management: Foundations for an investigation. Educational Theory, 58(3), 269–287.

Marginson, S. (2014). Academic freedom: A global comparative approach. Frontiers of Education in China, 9(1), 24–41.

Marginson, S., & Considine, M. (2000). The enterprise university: Power, governance and reinvention in Australia. Cambridge University Press.

Marginson, S. (1997). Markets in education. Allen & Unwin Sydney.

Matei, L. (2020). Charting academic freedom in Europe. In A. Curaj, L. Deca, & R. Pricopie (Eds.), European higher education area: Challenges for a new decade (pp. 455–464). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56316-528

McMann, K., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., Teorell, J., & Lindberg, S. (2022). Assessing data quality: An approach and an application. Political Analysis, 30(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2021.27

Mendes, C. H. (2020). Academic freedom in Brazil. In K. Kinzelbach (Ed.), Researching academic freedom: Guidelines and sample case studies (pp. 63–102). FAU University Press.

Pelke, L., & Spannagel, J. (2023). Quality assessment of the academic freedom index: Strengths, weaknesses, and how best to use it. V-Dem Working Paper No. 2023:142. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4495392

Pelke, L., & Croissant, A. (2021). Conceptualizing and measuring autocratization episodes. Swiss Political Science Review, 27(2), 434–448.

Pelke, L. (2023). Academic freedom and the onset of autocratization. Democratization, 30(6), 1015–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2023.2207213

Pemstein, D., Marquardt, K. L., Tzelgov, E., Wang, Y.-T., Medzihorsky, J., Krusell, J., Miri, F., & von Römer, J. (2023). The v-dem measurement model: Latent variable analysis for cross-national and cross-temporal expert-coded data. V-Dem Working Paper No. 21. 8th edition. https://v-dem.net/media/publications/Working_Paper_21_z5BldB1.pdf

Ramanujam, N., & Wijenayake, V. (2022). The bidirectional relationship between academic freedom and rule of law: Hungary, Poland and Russia. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 14(1), 27–48.

Skaaning, S.-E. (2020). Waves of autocratization and democratization: A critical note on conceptualization and measurement. Democratization, 27(8), 1533–1542. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1799194

Spannagel, J., Kinzelbach, K., & Saliba, I. (2020). The academic freedom index and other new indicators relating to academic apace: An introduction. V-Dem User-Working Paper No. 26. https://v-dem.net/media/publications/users_working_paper_26.pdf

Spannagel, J., & Kinzelbach, K. (2022). The academic freedom index and its indicators: Introduction to new global time-series v-dem data. Quality & Quantity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01544-0

Taylor, B. J., Kunkle, K., & Watts, K. (2022). Democratic backsliding and the balance wheel hypothesis: Partisanship and state funding for higher education in the United States. Higher Education Policy, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-022-00286-w

Acknowledgements

This research has greatly benefited from the outstanding work of colleagues at the V-Dem Institute, who developed the ERT package (https://github.com/vdeminstitute/ERT) and conceptualized and measured democratization and autocratization as episodes. Their work has been published in the Journal of Peace Research: https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433231168192. The idea to measure Academic Freedom Growth and Decline Episodes was inspired the instructive research on autocratization by Anna Lührmann and Staffan I. Lindberg as well as additional studies measuring episodes of regime transformation by V-Dem scholars. For the associated EpisodeR-package, I greatly benefited from the excellent and exemplary documentation of the ERT package. In addition, this paper benefited from feedback from Katrin Kinzelbach, and the two anonymous reviewers. I also thank Fabian Fassmann for skillful research assistance. All errors remain my own.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The author(s) received funding from the Volkswagen Foundation [grant number A138109], PI: Katrin Kinzelbach and Staffan I. Lindberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lott, L. Academic freedom growth and decline episodes. High Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01156-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01156-z