Abstract

Previous studies indicate that water storage over a large part of the Middle East has been decreased over the last decade. Variability in the total (hydrological) water flux (TWF, i.e., precipitation minus evapotranspiration minus runoff) and water storage changes of the Tigris–Euphrates river basin and Iran’s six major basins (Khazar, Persian, Urmia, Markazi, Hamun, and Sarakhs) over 2003–2013 is assessed in this study. Our investigation is performed based on the TWF that are estimated as temporal derivatives of terrestrial water storage (TWS) changes from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) products and those from the reanalysis products of ERA-Interim and MERRA-Land. An inversion approach is applied to consistently estimate the spatio-temporal changes of soil moisture and groundwater storage compartments of the seven basins during the study period from GRACE TWS, altimetry, and land surface model products. The influence of TWF trends on separated water storage compartments is then explored. Our results, estimated as basin averages, indicate negative trends in the maximums of TWF peaks that reach up to −5.2 and −2.6 (mm/month/year) over 2003–2013, respectively, for the Urmia and Tigris–Euphrates basins, which are most likely due to the reported meteorological drought. Maximum amplitudes of the soil moisture compartment exhibit negative trends of −11.1, −6.6, −6.1, −4.8, −4.7, −3.8, and −1.2 (mm/year) for Urmia, Tigris–Euphrates, Khazar, Persian, Markazi, Sarakhs, and Hamun basins, respectively. Strong groundwater storage decrease is found, respectively, within the Khazar −8.6 (mm/year) and Sarakhs −7.0 (mm/year) basins. The magnitude of water storage decline in the Urmia and Tigris–Euphrates basins is found to be bigger than the decrease in the monthly accumulated TWF indicating a contribution of human water use, as well as surface and groundwater flow to the storage decline over the study area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent studies report declining trends in terrestrial water storage (TWS, a vertical integration of surface water, soil moisture, groundwater, and biomass water content) over a large region of the Middle East and Western Asia (e.g., Voss et al. 2013; Forootan et al. 2014; Joodaki et al. 2014; Madani 2014; Al-Zyoud et al. 2015). The decline is believed to be mainly due to the climate change, as well as increasing demands on freshwater (surface water and groundwater) needed to support food production and economic activities of the increasing population in the region (UNEP 2003; Gleick 2004). In fact, decreasing the large-scale total water flux (TWF), known as precipitation ‘P’ minus evapotranspiration ‘E’ minus surface runoff ‘R’ (P–E–R), reflects a cumulative impact of direct and indirect anthropogenic modifications of the water cycle (e.g., Famiglietti and Rodell 2013; Eicker et al. 2015), and can be considered as an indicator of the ‘meteorological drought’ (e.g., Kusche et al. 2016). Kaniewski et al. (2012) discuss the climate change and water variability within the northwest part of the Middle East and show that variability in precipitation plays a critical role on crop yields, productivity, and economic systems within the region. Precipitation deficit therefore mainly causes the water storage deficit experienced in the Middle East.

Trigo et al. (2010) and Hosseinzadeh Talaee et al. (2014) indicate that a prolonged meteorological drought condition might contribute to water storage shortage in the region or its ‘hydrological drought’. In this study, large-scale TWS and TWF changes are assessed over the Tigris–Euphrates (shared by Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran and Kuwait) and Iran’s six major basins (defined according to FAO 2009), which cover a large area of the arid and semiarid parts of the Middle East. The aim is to understand the contributions of the TWF deficit and the human water use to the TWS decline during 2003–2013.

Monitoring networks to obtain meteorological (e.g., precipitation and evapotranspiration) and hydrological (water storage in surface and subsurface) parameters are quite sparse within the Middle East. Obtaining large-scale information (e.g., over trans-boundary river basins) is further compounded by the lack of trust between the countries or due to political interests. Such conditions, therefore, justify the exploration of alternative monitoring tools that can provide reliable information on meteorological and hydrological processes, which are necessary for managing drought and flood-related impacts, as well as improving the water resources management in the region (e.g., Greenwood 2014; Madani 2014).

Since late 2002, monthly TWS changes have been obtained by processing the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment mission (GRACE, Tapley et al. 2004) observations. GRACE’s unique products along with complementary observations (e.g., satellite altimetry) and modeling techniques (e.g., land surface model, ‘LSM,’ simulations) can be used for basin scale water balance studies (see, e.g., Kusche et al. 2012; Schumacher et al. 2016; Wouters et al. 2014 for a review). For example, GRACE and LSM were applied in Voss et al. (2013) to monitor groundwater variability over the Tigris–Euphrates river basin, and in Joodaki et al. (2014) to estimate anthropogenic contributions to groundwater loss over Iran. Both studies supported the model simulation results by Döll et al. (2012), which indicate that the rates of TWS decline due to anthropogenic water use reached up to 100 mm/year. Forootan et al. (2014) on their part introduced an inversion technique to estimate surface and subsurface water storage changes from GRACE combined with LSM simulations and altimetry observations. A multisensor approach was applied by Tourian et al. (2015) to separate the contribution of surface and subsurface storage compartments in the TWS decline over northwest Iran (the Urmia basin), where Urmia Lake has been shrinking. In both studies, negative rates of surface and subsurface storage changes are found to be significant and have accelerated since 2007.

Recent studies point to the fact that the contributions of climate change and hydrological processes are dominant drivers to water storage decline mainly within the Tigris–Euphrates river basin. For instance, Longuevergne et al. (2012) illustrate that surface water storage changes (estimated from altimetry measurements) within those regions that include lakes and reservoirs contribute to almost 50% of GRACE TWS trend. By combining various remote sensing data and LSM outputs in a hydrological model, Mulder et al. (2015) indicate that the GRACE TWS depletion within northern Iraq during 2007–2009 is mainly explained by a lake mass exploitation. In fact, hydrological processes such as surface and groundwater (lateral) flow might significantly change TWS patterns as has been discussed, e.g., in Scanlon et al. (2015). This impact is expected to be strong within the Tigris–Euphrates river basin and to a less extent within Iran’s river basins, e.g., Urmia and Persian basins, see, e.g., Hosseini and Ashraf (2015) for more details, and Fig. 1 for the location of the basins.

To obtain information on regional/global TWF changes, many studies use weather forecast model reanalysis products such as ERA-Interim from the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF, Dee et al. 2011), and the Modern Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA) from NASA (Rienecker et al. 2011). Lorenz and Kunstmann (2012), for example, assessed the representation of the hydrological cycle in three widely used reanalyses products provided by the European and American centers. Their results indicate that the TWF derived from reanalysis products might represent limited skills particularly due to biases, and the effects of anthropogenic modification that are particularly difficult to quantify (Simmons et al. 2010). Compared to in situ observations, skill of the reanalyses might change from a region to another (see, e.g., Forootan et al. 2016; Khandu et al. 2016). On the other hand, Rodell et al. (2004a) indicated that the temporal rate of changes in GRACE TWS is directly related to the changes in TWF through the water balance equation. Therefore, GRACE TWS estimations can be used to evaluate climate variability over river basins.

The contribution of this study is therefore threefold; (i) to apply TWF estimated from GRACE and reanalysis products for investigating possible changes in the seasonality (magnitude and spread of annual and semiannual peaks) and trends in the hydrological fluxes over 2003–2013, (ii) as large-scale ocean–atmosphere interactions potentially affect the rainfall and temperature of the region (e.g., Sabziparvar et al. 2010; Tabari et al. 2014); their contributions to the TWF changes are determined by considering the dominant climate variabilities associated with El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), and Mediterranean Oscillation (Hasanean 2004), and (iii) to apply the inversion methodology in Forootan et al. (2014) to separate GRACE TWS into surface and subsurface (soil moisture and groundwater) compartments. The trends and seasonality of the separated subsurface storage changes (in iii) are then explored, and their relationships to the TWF changes (in i and ii) discussed. Our motivation to address the variability in subsurface compartments is due to their importance for drought monitoring as soil moisture is the main driver of vegetation growth and consequently evapotranspiration (e.g., AghaKouchak et al. 2015), as well as groundwater that is the main source of freshwater within the arid and semiarid regions (e.g., Richey et al. 2015). It should be pointed out that for the signal separation, the methodology in Forootan et al. (2014) is adopted since, unlike other studies, it retains the spatial resolution of LSMs and GRACE gridded products (see e.g., Awange et al. 2014; Forootan 2014, Chap. 5.4), which is important for hydrological assessments (see e.g. Schumacher et al. 2016). The spatial coverage of the current contribution also extends the previous studies to cover the entire Iran and the Tigris–Euphrates river basin. To the best of our knowledge, variability in the TWF from GRACE and reanalysis products has not been addressed over the region.

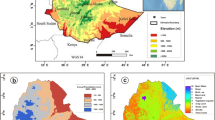

An overview of the study region that consists of the seven basins. The upper figure shows the average annual rainfall over the Middle East (FAO 2009), while the lower figure, the six main (first order) basins of Iran and the Tigris–Euphrates river basin are depicted by the red lines inside the satellite map

In the following, we describe the study region and its climate characteristics in Sect. 2, and four different types of data (reanalysis total fluxes, climate indices, GRACE TWS, and LSM simulations) in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, the main analysis techniques are introduced, while the results are reported in Sect. 5. Finally, in Sect. 6, a summary and conclusions are provided.

2 Study Region

A box extending from 29°–63°E and 24°–43°N is defined to extract TWS and TWF from GRACE, LSM, and reanalysis products. The six main (also called ‘first order’) basins of Iran (FAO 2009), and the Tigris–Euphrates river basin are considered in the study region, which have the following characteristics:

-

Iran covers a total area of about 1.75 million km2 (FAO 2009) and includes two large mountain chains; the Alborz that extends from the northwest to northeast and separates the dry central part from the green coastline regions of the Caspian Sea, as well as Zagros that runs from the northwest along the western border to the southern shore lines and continues to the southeastern boundaries. Considering the topography and hydrological conditions, the six main basins (catchments) are (1) ‘Khazar,’ 0.175 million km2, (2) ‘Persian Gulf and Oman Sea,’ 0.4375 million km2, (3) ‘Lake Urmia,’ 0.0525 million km2, (4) ‘Markazi’ (Central Plateau), 0.91 million km2, (5) ‘Hamun,’ 0.1225 million km2, and (6) ‘Sarakhs’ (Kara-Kum), 0.0525 million km2, which are shown in Fig. 1. In the following, basin (2) and (3) are simply referred to as ‘Persian’ and ‘Urmia,’ respectively. Iran is mostly located in an arid and semiarid climate except 10% of its area (Khazar), which has a subtropical condition. Annual precipitation falls from October through to April. An annual average of 228 mm precipitation is reported over Iran, which is considered as the main renewable water resource, with a maximum of 2227 mm in the Khazar basin and less than 50 mm in parts of the Markazi basin (FAO 2009). The very dry climate in the center (Markazi) is due to the particular extension of Alborz and Zagros that blocks atmospheric circulations and evaporation transport (Heshmati 2013).

-

The trans-boundary Tigris–Euphrates river basin with a total area of 0.88 million km2 is located to the west of Iran (see Fig. 1). The Tigris and Euphrates are the main rivers of this basin, which originate from the eastern mountains of Turkey and join at the south east of Iraq (called Shatt Al-Arab), and finally empty into the Persian Gulf. In addition to the northern mountains, some high mountains exist in the west of Tigris–Euphrates that are riparian only to the Euphrates and the extensive lowlands extend to the south and east. The climatic condition of Tigris–Euphrates varies from subtropical in the northern and mountainous parts to the arid and semiarid climate in the south.

3 Data

3.1 Reanalysis Flux Products

-

ERA-Interim is a global atmospheric reanalysis produced by ECMWF (Dee et al. 2011). Several gridded products, describing the ocean, land surface and the atmospheric (covering the troposphere and stratosphere) conditions have been produced in a fully integrated–coupled system. The system produces 3–6-hourly predictions with a spatial resolution of \({\sim}0.79^\circ \times 0.79^\circ\). Gridded precipitation (P), evapotranspiration (E), and runoff (R) products over 2003–2013 are downloaded from the ECMWF website (http://apps.ecmwf.int/datasets/) to estimate monthly (TWF, i.e., P–E–R) over the study region.

-

MERRA-Land is the latest American global reanalysis for the satellite era (1979 onwards) produced by NASA using the Goddard Earth Observing Data Assimilation version 5 (GEOS-5, Rienecker et al. 2011). The retrospective analyses is run at a relatively high spatial resolution (\(0.67^\circ \times 0.50^\circ\)) at 1–6 hourly time intervals focusing mainly on the assimilation of the global hydrological cycle by integrating a variety of observing systems (such as satellite- and ground-based observations). Monthly total fluxes are derived from the MERRA-Land through the website (http://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/research/merra/merra-land.php). Our motivation to select the ‘land’ component is due to the improved skill of MERRA-Land in reconstructing soil moisture and runoff over MERRA (see, e.g., Reichle et al. 2011).

3.2 Climate Variability Indices

Large-scale ocean–atmosphere interactions have a significant impact on the Earth’s climate and water resources (Moron et al. 1998). To characterize these oscillations, climate variability indices have been produced to represent the activities of major phenomena such as the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI, for ENSO), Mediterranean Oscillation Index (MOI), and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index that might have significant influences on the large-scale climate and water storage variability within our study region (Hasanean 2004).

-

ENSO is the largest inter-annual climate variability phenomenon in the Tropical Pacific, which affects the climate of many regions of the Earth (Trenberth 1990; Forootan et al. 2016). El Niño refers to the negative phase on ENSO that brings winter precipitation to the Middle East and the opposite phase La Niña causes less than normal precipitation variability (Nazemosadat and Cordery 2000). ENSO events are calculated using the pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin and represented by SOI (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/teleconnections/enso/indicators/soi/).

-

MOI is computed from sea level pressure over the western and eastern Mediterranean Sea that generates regional circulations affecting the climate of Europe and the Middle East (Martin-Vide and Lopez-Bustins 2006). During negative MOI phases, the probability of above average winter precipitation is significantly less than the positive phases. From several versions of existing MOI, this study employs the Algiers-Cairo MOI, which is based on the normalized pressure difference between Algiers (36.4°N, 3.1°E) and Cairo (30.1°N, 31.4°E) (Conte et al. 1989). This index is downloaded from the Climatic Research Unit (http://www.cru.uea.ac.uk/data).

-

NAO is a multiannual variability in the atmosphere, which is most pronounced in winter. It is characterized with the NAO index, which is defined as the pressure difference between Ponta Delgada, Azores (38°N, 26°W) and Akureyri Iceland (66°N, 18°W) (Rogers 1984). During the positive phase of NAO (negative phase of NAO), stronger (weaker) than usual surface winds and wintertime storms move from west to east across North Atlantic (Cullen and deMenocal 2000). As a result, wetter and warmer (drier and cooler) winter conditions occur over the northern Europe and the east coast of the USA, while drier and cooler winters occur over Greenland and the Mediterranean extending into the Middle East (Ghasemi and Khalili 2008).

3.3 Total Water Storage Products from GRACE

GRACE Level 2 products consist of (almost) monthly gravity field solutions that have been released from three different processing centers. The latest release of the gravity field solutions up to degree and order 90 and are available from the official providers CSR, GFZ, and JPL. Following the recommendations in Sakumura et al. (2014), this study employs an ensemble mean of these fields (covering 2003–2013) to reduce the noise. Degree 1 coefficients are replaced by those in Swenson et al. (2008) in order to account for variations in the Earth’s center of figure with respect to the Earth’s center of mass. The zonal degree 2 spherical harmonic coefficients \((C_{20})\) are replaced by those in Cheng et al. (2013) (see also http://grace.jpl.nasa.gov) since they are found to be better estimated.

GRACE Level 2 products contain correlated errors (due to measurement errors, sampling of the mission, and background errors, see, e.g., Forootan et al. 2013 and Schumacher et al. 2016), which express themselves as striping patterns in the spatial domain. These errors mask hydrological signals and make their detection difficult (Kusche 2007). Before computing monthly TWS fields, the DDK2 decorrelation filter (Kusche et al. 2009) is applied to suppress the correlated noise. Monthly residual gravity field solutions are computed by subtracting the temporal average of 2003–2013 from each month. The residual coefficients are then transformed into \(1^\circ \times 1^\circ\) grid of TWS over the study region following Wahr et al. (1998). It is worth mentioning here that GRACE TWS estimations are affected by signal attenuation and leakage due to the spatial averaging introduced by the filtering techniques. These errors impact on the estimated long-term trends. From the assessed basins, TWS estimations of Khazar, Urmia, and Sarakhs exhibit bigger leakage errors than the other basins due to their smaller area and the existing mass anomalies. For example, spatial leakage associated with the strong water fluctuations within the Caspian Sea and the strong storage trend in Urmia Lake influence the estimation of changes in soil moisture and groundwater storage compartments of their surrounding regions (see also Longuevergne et al. 2012).

3.4 Global Land Surface Models

The Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS, Rodell et al. 2004b) is a land surface model (LSM), which has been fed by meteorological forcing and employing data assimilation techniques. GLDAS provides off-line near-real-time datasets with global coverage. The water balance components from three versions of GLDAS, i.e., NOAH, MOSAIC, and VIC at \(1^\circ \times 1^\circ\) (http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/hydrology/data-holdings) are used as a priori information to separate GRACE TWS (see Sect. 4.1). From each model output, a vertical summation of the total column soil moisture (TSM), snow water equivalent (SWE), and canopy water storage (CWS) are used. Note that the groundwater variations are not simulated by GLDAS and will be computed as a residual of TWS and other storage compartments. The possible lateral water storage flow has not been explicitly considered in the GLDAS simulations, which might be important within the Tigris–Euphrates river basin.

A summary of the datasets used in this study is presented in Table 1. All the gridded datasets of various spatial and temporal resolutions were averaged to a common grid of \(1^\circ \times 1^\circ\) at monthly scales for a fair comparison that is described in the following section.

3.5 Post-processing of TWS and TWF Products

3.5.1 Proper Filtering of TWS Derivatives and Reanalysis Fluxes

Considering the water balance equation \(\frac{\delta W(t)}{\delta t} = P(t) -E(t) -R(t)\) (Rodell et al. 2004a), the right-hand side should be replaced by monthly reanalysis products (here ERA-Interim and MERRA-Land), and the left-hand side by estimating a numerical derivative of the GRACE TWS time series. In this formulation, the runoff is simulated from the land component of ERA-Interim and MERRA-Land. This simulation has already improved the representation of the reanalysis outputs when compared to remote sensing and in situ observations (Reichle et al. 2011). The rate of storage change \(\frac{\delta W(t)}{\delta t}\) for a particular month is computed by averaging the two preceding and following months using a central differentiation operator (\(1/8 , 1/4, -1/4, -1/8\)). However, this operation has a smoothing effect, and therefore, a proper filter should be applied to P–E–R to avoid possible phase shifts. This is done by convolving an optimum (temporal) central smoothing filter (2/44, 11/44, 18/44, 11/44, 2/44) with DDK2-filtered reanalysis TWF (P–E–R) time series as suggested by Eicker et al. (2015).

3.5.2 Filtering of LSM Storage Simulations

GRACE Level 2 products are (i) originally expanded in terms of spherical harmonics and (ii) filtered using the DDK2 (a low-pass filter) to suppress the noise. Both (i) and (ii) introduce a smoothing (damping) impact to the signal content of GRACE products. In order to have similar spectral structure as those of GRACE TWS, storage simulations of the LSMs are first expanded to the spherical harmonic domain using a numerical integration as in Wang et al. (2006). Then, the DDK2 filter is applied to smooth the storage products. This procedure is consistent with the post-processing in Forootan et al. (2014).

4 Method

4.1 Inversion to Separate GRACE TWS into Storage Compartments

In terms of storage compartments, GRACE TWS over the study region consists of storage changes in soil moisture (\({{\bf X}}_{{\text {Soil}}}\)), groundwater (\({\bf X}_{\text {Groundwater}}\)), canopy (\({\bf X}_{\text {Canopy}}\)), snow (\({\bf X}_{\text {Snow}}\)), and surface water \({\bf X}_{{\text {Surface}}\,{\text{water}}}\). Thus,

where storage changes of \({\bf X}_{\text {Soil}}, {\bf X}_{\text {Canopy}}\), and \({{\bf X}}_{\text {Snow}}\) can be obtained from GLDAS model simulations. Estimations of \({{\bf X}}_{{\text {Surface}}\,{\text{water}}}\) can be introduced by converting altimetry measurements to storage following, e.g., Moore and Williams (2014). Groundwater (\({{\bf X}}_{\text {Groundwater}}\)) estimation is missing in land surface models such as GLDAS and therefore is estimated here after solving the inversion.

Forootan et al. (2014) demonstrated that a direct reduction of subsurface and surface storage compartments from GRACE TWS to estimate, e.g., groundwater variability over the region might be erroneous. This is due to the fact that (a) hydrological model simulations and altimetry measurements are not perfectly consistent with GRACE TWS estimations and (b) GRACE-derived TWS estimation is contaminated by spatial leakages, which should be addressed by applying a proper post-processing technique (e.g., Long et al. 2015).

In this study, similar to Forootan et al. (2014), surface storage (from altimetry) and other compartments from GLDAS are used as a priori information for an inversion process. Therefore, the time series of soil moisture, canopy, snow, and surface water over the study region (29°–63°E and 24°–43°N, and covering 2003–2013) are decomposed using temporal-independent component analysis (tICA, Forootan and Kusche 2012, 2013) into independent temporal patterns and associated spatial base functions as

where A contains temporal and S stores spatial patterns. Then, the spatial patterns (in S) are considered as invariant and are fitted to GRACE TWS to estimate updated temporal patterns that are consistent with GRACE observations as

where \({\bf X}_{\text {TWS}}\) contains GRACE TWS time series. To reconstruct the contribution of each storage compartment, one can use the updated temporal variability in Eq. (3) and their corresponding invariant spatial patterns as

The reconstructed values in Eq. (4) are consistent with GRACE TWS estimations (since the temporal patterns have been fitted to GRACE within the inversion). The separated storage compartments are of the same spatial resolution as the introduced LSM and altimetry-derived base functions. This feature was missing in most of previous studies as they only presented basin average mass variations. As different LSM products have been used in the inversion procedure, i.e., by inserting each product in Eqs. (2)–(3), accordingly, a new estimation of the storage compartments that provides a chance to estimate uncertainty of the separated compartments is derived. This uncertainty has been considered in the trend estimation performed in the following sections. Groundwater variability over the region of study is then computed as the differences between GRACE TWS and the reconstructed storage compartments (from Eq. (4)) as

4.2 Stepwise MLR Method

In order to extract trends, seasonal, and climate variability from TWF time series, multiple linear regression (MLR) that contains a trend component (e.g., linear), periodic components (e.g., annual and semiannual cycles), and normalized climate indices is applied to account for variability associated with large-scale phenomena, i.e.,

where y(t) contains the time series of observations (e.g., total fluxes) at time t. MLR coefficients, determined using least squares adjustment (LSA), consist of \(\beta _0\) as an offset depending on the starting point of the time series, \(\beta _1\) representing the linear trend, \(\beta _2\) and \(\beta _3\) for the annual cycle, \(\beta _4\) and \(\beta _5\) corresponding to the semiannual cycle, \(\beta _6\) and \(\beta _7\) indicating changes due to the Mediterranean Oscillation, \(\beta _8\) and \(\beta _9\) representing changes due to NAO, and finally, changes due to ENSO described by \(\beta _{10}\) and \(\beta _{11}\). In Eq. (6), \({\text{ M }}(t), {\text{ N }}(t)\), and \({\text{ S }}(t)\) indicate temporally normalized time series of MOI, NAO, and SOI, respectively. The annual and semiannual cycles have already been removed from the time series of these indices before being inserted in Eq. (6). To extract the out-of-phase changes of observations, the Hilbert transformation (\({{\mathcal {H}}}(.)\), Horel 1984) is used to shift the time series of indices in the frequency domain by \(90^\circ\) (see also, Forootan et al. 2016). Finally, \(\epsilon (t)\) is assumed to be an independent error term, which follows a normal distribution \((\epsilon \sim N(0,\sigma _{\epsilon }^2))\) and stands for the deviations between observations and the MLR model. The time series of climate indices (including the annual and semiannual cycles) and their respective Hilbert transforms are shown in Fig. 2.

In order to find a significant MLR model with the best fit, Eq. (6), it is applied iteratively by systematically adding and removing coefficients \(\beta _{0}\) to \(\beta _{11}\) and testing the statistical significance of the regression. This approach, known as the stepwise regression (Draper and Smith 1998), begins with an initial model (Eq. (6)) and then compares the explanatory power of incrementally larger and smaller models. The goal of variable selection in the stepwise method is to achieve a balance between simplicity (as few predictive terms as possible) and fit (as many predictive terms as needed). In general, the order of adding/removing parameters does not change the final results of the implemented step-wise regression. However, one must make sure that the time series of climate indices (used here as base-functions during fitting the models) are not highly dependent.

4.2.1 Testing MLR Coefficients

In order to assess whether a MLR model is globally significant, we formulate a null hypothesis test by considering all coefficients at the same time as \(H_0{:}\,\beta _0=\cdots =\beta _{11}=0\) (Hoffmann 2010). The significance of the MLR results is evaluated based on the p value of an F-statistic that is defined as the lowest significance level at which a null hypothesis can be rejected. For any \(\alpha < p\) value, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, while the null hypothesis is rejected when \(\alpha > p\) value. At each step of the stepwise MLR, the p value of an F-statistic is computed to test the significance of the MLR model with and without a particular predictor. If a term is currently in the model, the null hypothesis is that the term would have a zero coefficient if added to the model as in Draper and Smith (1998).

5 Results

First, the quality of GRACE estimated TWF against those of reanalysis derived from ERA-Interim and MERRA-Land is assessed. The same post-processing described in Sect. 3.5 is applied to both products. Correlation coefficients between the TWF estimates derived from GRACE and ERA-Interim/MERRA-Land indicate a slightly better agreement between GRACE and ERA-Interim compared to between GRACE and MERRA-Land (see figures in the Appendix). A comparison between basin-averaged GRACE and ERA-Interim total fluxes is also shown in the Appendix, which indicates a high agreement in most of the basins except within Markazi (the driest basin) and the semiarid Hamun. The TWF products are compared after removing the seasonal cycles, where the residual signals are still found to be consistent (results are not shown here). However, the correlation decreased as the annual cycle significantly contributed to the correlation values.

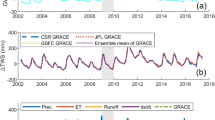

Basin average TWF is computed from GRACE and reanalysis for the seven basins, and the results are plotted in Fig. 3. GRACE basin averages are estimated in the spectral domain following Kusche et al. (2011). Error bars for GRACE derivatives are obtained by propagating the errors of GRACE products obtained from CSR. Consistent with previous studies, e.g., Long et al. (2014), the TWF changes from GRACE indicate a considerable noise after 2011, which is likely due to increase in the magnitude of errors in GRACE TWS products. All the TWF estimations are temporally centered, as we do not interpret the (uncertain) constant bias between GRACE TWF and the reanalyses. The overall comparisons indicate that the TWF estimates from ERA-Interim represent a better fit to those of GRACE (confirming the correlation results in the Appendix). The TWF estimations of MERRA-Land represent smaller amplitudes than those of GRACE and ERA-Interim except in the three basins of Tigris–Euphrates, Khazar and Urmia, which receive more precipitation than the other basins. A comparison between the global GRACE TWF and those from reanalysis products is provided in Eicker et al. (2015) whose results indicate that the skill of reanalysis products changes from one location to another, making a report on the superiority of one against the other difficult.

In Table 2, the linear trends fitted to the peaks of the basin-averaged GRACE TWF are presented. The peaks are selected for estimation since in the semiarid regions, the amount of peak to peak changes in TWF is the main driver of yearly TWS changes (see similar computation in, e.g., Swenson and Wahr 2009). Trends are computed during the shorter time drought period of 2003–2007 and 2007–2013 (after the meteorological drought), as well as over the entire period of study 2003–2013. During the period of 2003–2007, strongest decreasing trends (that likely indicate the impacts of meteorological drought) are found over Urmia, Tigris–Euphrates, Persian, Markazi, and Hamun. The linear trend of the TWF time series within the Sarakhs basin is found to be increasing. The linear trends over 2007–2013 are found to be mostly positive, making the overall trend (2003–2011) smaller than those of 2003–2007 as can be seen in Table 2. As the spread of seasonal peaks remains almost constant during the period of study, one can conclude that, over 2003–2007, the region exhibited an overall meteorological drought as has been reported by FAO (2009). Since the estimated linear trends in TWF are equivalent with the accelerations of TWS changes, one can see from Table 2 that the period of assessment is important for drawing a conclusion. For example, the most significant water depletion (TWS acceleration) is found during the 2003–2007 period in most of the assessed basins. A comparison between annually accumulated TWF and TWS is presented in Sect. 5.2.

Comparison between basin-averaged TWFs from GRACE products (TWS derivatives) and those from reanalysis ERA-Interim and MERRA-Land products. The graphs correspond to Iran’s six major river basins and the Tigris–Euphrates river basin. The time series are centered with respect to their temporal means. The green lines represent the linear trend fitted to the TWF peaks

5.1 Exploring Total Flux Changes by Stepwise MLR

In this section, Eq. (6) is used to examine the contribution of seasonal components (annual and semiannual) along with dominant climate variability in the region (introduced by de-seasoned climate indices) in the TWF changes of the seven river basins. The best fitted models that describe the basin averages of Fig. 3 are determined using stepwise MLR (Sect. 4.2), and the results are summarized in Table 3. The results show that the dominant variability of TWF is mainly related to the annual components. From the climate variability indices, SOI is found to be significant over the Tigris–Euphrates and Urmia basins; NAO over Khazar (see also, Cullen and deMenocal 2000; Cullen et al. 2002; Turkes and Erlat 2003); and MOI affecting the TWF variability in the Persian, Markazi, and Sarakhs basins. No significant influences of the examined indices are found over the Hamun basin. Table 3 shows the best fitted models adjusted to the basin average TWF time series and summarizes the statistics obtained from the fittings. The coefficients of the best fitted models in Table 3 are estimated via a least squares adjustment and the amplitudes of the significant components are presented in Table 4.

The significance of the above fitted models for the TWF time series of each grid point within the study region is also examined by estimating the p values. Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution of the p value, in which those time series that do not reject the null hypothesis are shown in red. The results indicate that the estimated models (Table 3) fairly well describe the TWF variability in the study region.

Test results to assess the significance of the fitted MLR models (Table 3) fitted to the GRACE TWF time series (spatial distribution of the p values). Insignificant regions are shown by red color

5.2 Inverted Soil and Groundwater Storage Changes

The inversion method presented in Sect. 4.1 is applied here to estimate storage variability in soil layers and groundwater compartments. Considering Eq. (1), a priori information of soil moisture, canopy, and snow are obtained from the GLDAS models (Sect. 3.4) over a box 29°–63°E and 24°–43°N (that includes the seven basins), covering the period 2003–2013. Information on the surface water compartment is obtained by converting altimetry measurements over the Caspian Sea, Persian and Oman Gulfs, Lake Urmia (\(37^\circ 42'\)N \(45^\circ 19'\)E), and Lake Tharthar (\(33^\circ 58'\)N \(43^\circ 11'\)E) to storage changes following Moore and Williams (2014). All altimetry measurements are downloaded from (http://www.pecad.fas.usda.gov/cropexplorer/global_reservoir/) except those of the Persian and Oman Gulfs from (http://www.star.nesdis.noaa.gov/sod/lsa/SeaLevelRise/LSA_SLR_timeseries.php). The surface water storage changes of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and Red Sea are not considered here since they represent negligible spatial leakage compared to the storage signals of the considered river basins (see also, Forootan et al. 2014).

The time series of soil moisture, canopy, snow, and surface water are decomposed using the tICA (Eq. 2) into independent temporal patterns (A) and associated spatial base functions (S). The spatial patterns S are chosen as invariant base functions and fitted to GRACE TWS (using Eq. 3) to estimate updated temporal patterns. Their individual contributions are then reconstructed using Eq. (4). Groundwater variability over the region of study is computed using Eq. (5). The details of this fitting is very similar to that of Forootan et al. (2014), therefore, the results are not shown here.

Time series of GRACE TWS, groundwater, and soil moisture changes are estimated for the Tigris–Euphrates and Iran’s six major basins, and the results shown in Fig. 5. From the storage compartments, we only show those of soil moisture and groundwater since their contribution to TWS changes is bigger than the others. GRACE TWS basin averages are computed in the spectral domain as in Kusche et al. (2011). In Fig. 5, black lines indicate an average of GRACE TWS computed using GFZ, CSR, and JPL products and basin averages of the reconstructed soil moisture changes are shown by the blue lines. Finally, groundwater basin averages (red lines) are estimated as the differences between GRACE TWS (black lines) and the fitted soil moisture estimations (blue lines). It is worth mentioning that the uncertainty of the signal separation is computed by repeating the inversions by introducing MOSAIC, NOAH, and VIC as inputs for soil moisture, canopy, and snow variability, as well as by introducing GRACE TWS errors from the CSR products. Although the error bars are not shown in Fig. 5, their impacts on the trend estimation are considered and shown in Fig. 6.

Time series of GRACE TWS, groundwater, and soil moisture changes (in mm) derived for the seven river basins of this study. Black lines are computed by averaging GRACE TWS from GFZ, CSR, and JPL products. Solid blue lines represent an average of reconstructed soil moisture estimations using NOAH, MOSAIC, and VIC as priori information. Solid red lines show the average of groundwater estimations. Dashed lines correspond to the inversion results estimated by inserting various a priori storage compartments. The error bars are not shown in this figure

The largest annual amplitude of groundwater is found over the Khazar, Sarakhs, and Tigris–Euphrates basins. The biggest soil moisture seasonality is found in the Urmia, Tigris–Euphrates, and Persian basins. Over the Khazar, Hamun, Markazi, and Sarakhs basins, the seasonality of soil moisture and groundwater is found to be similar. The results corroborate the fact that a better understanding of groundwater changes is essential for hydrological and geophysical studies. Table 5 summarizes the annual amplitudes of TWS, soil moisture, and groundwater in each basin. The results of Fig. 5 indicate that most of the basins exhibited water storage decline during the period of study. Error bars are estimated by propagating the uncertainty of each storage compartment to the linear trend component (Koch 1999). Bigger negative trends in future soil moisture and groundwater changes is expected as it has been suggested by future climate projections, e.g., simulated in IPCC-CMIP5 over 2020–2050 (see e.g., Zahid et al. 2014).

The linear trends of soil moisture and groundwater changes over the whole period of 2003–2013 and the shorter period of 2007–2013 are estimated (see Fig. 6). The shorter period is selected to assess whether the rate of decline in water storage has changed after 2007 since both the TWF time series (Fig. 3) and the storage results of Fig. 6 indicate a change in the temporal evolution in 2007. Comparing the rates in Fig. 6, a negative acceleration in soil moisture changes can be seen over all the basins except Urmia (~−11.2 mm/year) and Tigris–Euphrates (~−6.5 mm/year). The rate of change in groundwater over the Persian basin is found being close to zero and almost steady through the period of study, while within the Tigris–Euphrates river basin, a steady decline of groundwater at a rate of ~−5.7 mm/year is found. Over the other basins, the groundwater depletion has increased as can be seen in Fig. 6. The trend and acceleration of the groundwater storage compartment within most of the basins is very different from those of soil moisture and cannot be explained by changes in the reanalysis TWF time series of Fig. 3. To illustrate this, monthly reanalysis TWF rates are converted to monthly storage and accumulated over each year. The results are then compared to the accumulated GRACE TWS basin averages that are shown in Fig. 7. Within the Hamun, Persian, and Markazi basins, we find fairly good correspondence between accumulated storage changes as all the curves indicate similar trends and fluctuations. Within Khazar, Urmia, Sarakhs, and Tigris–Euphrates basins, however, the storage changes estimated from reanalyses are different from GRACE mainly after 2008. A part of the differences can be explained with the longer memory of TWS changes, which was under influence of the long-term meteorological drought (before 2008). Thus, only few normal or high seasons of rainfall might not be able to change the trend of TWS. Human use impact, such as irrigations or over exploitation of groundwater within these basins as reported in previous studies, e.g., Voss et al. (2013) and Al-Zyoud et al. (2015), is another possible interpretation that describes the differences between GRACE and reanalysis results.

In order to better understand the behavior of water storage changes within the study region, tICA (Eq. 2) is applied to extract the main temporally independent patterns of the reconstructed soil moisture (Eq. 4) and estimated groundwater (Eq. 5) time series. Figure 8a shows the first two dominant independent modes of soil moisture in which the first mode (spatial and temporal IC1 in Fig. 8a) indicates annual changes while the second mode (spatial and temporal IC2 in Fig. 8a) shows a linear trend over the region. Both modes together represent \({\sim }\)62% of soil moisture variability over the study area. The annual amplitude is found to be stronger (exceeding 150 mm) over the north and west of Iran, as well as Turkey. Negative soil moisture trends are found to be distributed mostly over the Tigris–Euphrates, Khazar, Urmia, Persian, and Markazi basins. Since the study region exhibits a strong depletion in groundwater, the first independent mode of groundwater shows the distribution of linear trend (spatial and temporal IC1 in Fig. 8b), while the annual oscillation of the groundwater is captured by the second mode (spatial and temporal IC2 in Fig. 8b). Strong groundwater storage decrease is found over the southern part of Tigris–Euphrates and the northern part of Persian (with a rate of up to −60 mm/year). Positive groundwater trends (with a rate of up to 38 mm/year) are found along the Zagros chain (boundary of the Markazi and Persian basins), which is likely caused by the ice melting accelerated after 2007. A part of the trend might be due to the uplift, which might reach 5 mm/year (Oveisi et al. 2009). Further research should be done to accurately separate the observed deformation and storage signals. The annual amplitudes of groundwater are found to be almost half of the annual soil moisture variability, but over some regions it reaches almost 110 mm. It is worth mentioning that no obvious trend exists in the annual modes of soil moisture and groundwater (respectively, IC1 in Fig. 8a and IC2 in Fig. 8b). Considering the whole 2003–2013, the annual amplitude of 2007–2009 is found to be smaller. This observations suggest that the contribution of human water use in the storage decline of the study area is likely dominant.

6 Summary and Conclusions

Previous studies indicate that water storage over a large area of the Middle East has been decreasing over the last decade. However, fewer attempts have been made to quantify the changes in the amount of total water flux [TWF, as precipitation (P), evapotranspiration (E), and river discharge (R), and separate compartments of the terrestrial water storage (TWS), including soil moisture and groundwater and other compartments]. These have been assessed in this study over the Tigris–Euphrates river basin and Iran’s six major basins covering 2003–2013. Skills of the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) products to represent the TWF (P-E-R) is compared to the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalysis (ERA-Interim) and the Modern Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA-Land) products. Our results indicate a negative trend in the TWF over the study region that is most likely due to the reported meteorological drought. Using a stepwise multilinear regression technique, the contribution of climate indices in the TWF changes is identified. The contribution of the Southern Oscillation Index (a representative of the El Niño Southern Oscillation) is found to be significant over the Tigris–Euphrates and Urmia. The Mediterranean Oscillation Index is found to be significant over the Persian, Markazi, and Sarakhs basin, while North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) is found being only significant over the Khazar basin (see Table 4 for the amount of contributions).

An inversion technique is also applied to separate GRACE TWS into soil moisture and groundwater compartments. A decomposition of the separated results into (temporally) statistically independent components (Sect. 5.2) indicates negative soil moisture trends over the Tigris–Euphrates, Khazar, Urmia, Persian, and Markazi basins (see Fig. 8). Strong groundwater storage decrease is found over the southern part of the Tigris–Euphrates river basin and the northern part of the Persian basin. The rates of storage decline over the period of 2003–2013 (Fig. 6) in the groundwater compartment are, however, bigger than the decrease in the soil moisture compartment (Table 2). Within the basins with significant agricultural activity, e.g., Khazar, Urmia, and Tigris–Euphrates, the annual accumulated GRACE TWS is found to be different from those estimated by converting reanalysis TWF to storage changes mainly after 2008. This likely suggests that the contribution of human water use represents a dominant impact on the storage decline of these basins.

References

AghaKouchak A, Farahmand A, Teixeira J, Wardlow B, Melton F, Anderson M, Hain C (2015) Remote sensing of drought: progress, challenges and opportunities. Rev Geophys 53(452–480):1002. doi:10.758/2014RG000456

Al-Zyoud S, Rühaak W, Forootan E, Sass I (2015) Over exploitation of groundwater in the centre of Amman Zarqa basin-Jordan: evaluation of well data and GRACE satellite observations. Resources 4:819–830. doi:10.3390/resources4040819

Awange J, Forootan E, Kuhn M, Kusche J, Heck B (2014) Water storage changes and climate variability within the Nile Basin between 2002–2011. Adv Water Resour 73:1–15. doi:10.1016/j.advwatres.2014.06.010

Balsamo G, Albergel C, Beljaars A, Boussetta S, Brun E, Cloke H, Dee D, Dutra E, Muñoz-Sabater J, Pappenberger F, de Rosnay P, Stockdale T, Vitart F (2015) ERA-Interim/Land: a global land surface reanalysis data set. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 19:389–407. doi:10.5194/hess-19-389-2015

Cheng M, Tapley BD, Ries JC (2013) Deceleration in the Earth’s oblateness. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 118:740–747. doi:10.1002/jgrb.50058

Colin CA, Windmeijer FAG (1997) An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. J Econom 77(2):329–342. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(96)01818-0

Conte M, Giuffrida A, Tedesco S (1989) The Mediterranean Oscillation: impact on precipitation and hydrology in Italy. Conference on climate and water. Publications of the Academy of Finland, Helsinki

Cullen HM, deMenocal PB (2000) North Atlantic influence on Tigris–Euphrates streamflow. Int J Climatol 20:853–863. doi:10.1002/1097-0088(20000630)20:8<853::aid-joc497>3.0.co;2-m

Cullen HM, Kaplan A, Arkin PA, Demenocal PB (2002) Impact of the north Atlantic oscillation on the Middle Eastern climate and streamflow. Clim Change 55:315–338. doi:10.1023/A:1020518305517

Dee DP et al (2011) The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137:553–597. doi:10.1002/qj.828

Döll P, Hoffmann-Dobrev H, Portmann FT, Siebert S, Eicker A, Rodell M, Strassberg G, Scanlon BR (2012) Impact of water withdrawals from groundwater and surface water on continental water storage variations. J Geodyn 59–60:143–156. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2011.05.001

Draper NR, Smith H (1998) Applied regression analysis. Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken. doi:10.1002/9781118625590

Eicker A, Forootan E, Springer A, Longuevergne L, Kusche J (2015) Does GRACE see the terrestrial water cycle ‘intensifying’? J Geophys Res Atmos 121:733–745. doi:10.1002/2015JD023808

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO (2009). FAO Water Report 34

Famiglietti JS, Rodell M (2013) Water in the balance. Science 340:1300–1301. doi:10.1126/science.1236460

Forootan E (2014) Statistical signal decomposition techniques for analyzing time-variable Satellite gravimetry data. Ph.D. thesis, University of Bonn, Germany. http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/2014/3766/3766.htm

Forootan E, Kusche J (2012) Separation of global time-variable gravity signals into maximally independent components. J Geod 86(7):477–497. doi:10.1007/s00190-011-0532-5

Forootan E, Kusche J (2013) Separation of deterministic signals using independent component analysis (ICA). Stud Geophys Geod 57(1):17–26. doi:10.1007/s11200-012-0718-1

Forootan E, Didova O, Kusche J, Löcher A (2013) Comparisons of atmospheric data and reduction methods for the analysis of satellite gravimetry observations. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 118:2382–2396. doi:10.1002/jgrb.50160

Forootan E, Rietbroek R, Kusche J, Sharifi MA, Awange JL, Schmidt M, Famiglietti J (2014) Separation of large scale water storage patterns over Iran using GRACE, altimetry and hydrological data. Remote Sens Environ 140:580–595. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2013.09.025

Forootan E, Khandu K, Awange JL, Schumacher M, Anyah RO, van Dijk AIJM, Kusche J (2016) Quantifying the impacts of ENSO and IOD on rain gauge and remotely sensed precipitation products over Australia. Remote Sens Environ 172:50–66. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2015.10.027

Ghasemi AR, Khalili D (2008) The association between regional and global atmospheric patterns and winter precipitation in Iran. Atmos Res 88:116–133. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2007.10.009

Gleick PH (2004) Global freshwater resources: soft-path solutions for the 21st century. Science 302:1524–1528. doi:10.1126/science.1089967

Greenwood S (2014) Water insecurity, climate change and governance in the Arab world. Middle East Policy 21(2):140–156. doi:10.1111/mepo.12077

Hasanean HM (2004) Middle East meteorology. UNESCO-EOLSS Joint Committee Secretariat, Paris

Heshmati AG (2013) Indigenous plant species from the drylands of Iran, distribution and potential for habitat maintenance and repair. In: Heshmati GA, Squires VR (eds) Combating desertification in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Springer, New York

Hoffmann JP (2010) Linear regression analysis: applications and assumptions, 2nd edn. Brigham Young University, Provo

Horel JD (1984) Complex principal component analysis: theory and examples. J Clim Appl Meteorol 23:1660–1673. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1984)023<1660:CPCATA>2.0.CO;2

Hosseini M, Ashraf MA (2015) Application of the SWAT model for water components separation in Iran. Springer Hydrogeology. ISSN: 2364-6454

Hosseinzadeh Talaee P, Tabari H, Ardakani S (2014) Hydrological drought in the west of Iran and possible association with large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns. Hydrol Process 28:764–773. doi:10.1002/hyp.9586

Joodaki G, Wahr J, Swenson S (2014) Estimating the human contribution to groundwater depletion in the Middle East, from GRACE data, land surface models, and well observations. Water Resour Res 50:2679–2692. doi:10.1002/2013WR014633

Kaniewski D, Van Campoa E, Weiss H (2012) Drought is a recurring challenge in the Middle East. PNAS 109(10):3862–3867. doi:10.1073/pnas.1116304109

Khandu Awange JL, Kuhn M, Anyah R, Forootan E (2016) Changes and variability of precipitation and temperature in the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna River Basin based on global high-resolution reanalyses. J Climatol Int. doi:10.1002/joc.4842

Koch KR (1999) Parameter estimation and hypothesis testing in linear models, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Kusche J (2007) Approximate decorrelation and non-isotropic smoothing of time-variable GRACE-type gravity field models. J Geod 81:733–749. doi:10.1007/s00190-007-0143-3

Kusche J, Schmidt R, Petrovic S, Rietbroek R (2009) Decorrelated GRACE time-variable gravity solutions by GFZ, and their validation using a hydrological model. J Geod 83:903–913. doi:10.1007/s00190-009-0308-3

Kusche J, Eicker A, Forootan E (2011) Analysis tools for GRACE and related data sets, theoretical basis. The International Geoscience Programme (IGCP). IGCP 565: Supporting water resource management with improved Earth observations. www.igcp565.org/workshops/Johannesburg_2011/_LectureNotes_analysistools.pdf

Kusche J, Klemann V, Bosch W (2012) Mass distribution and mass transport in the Earth system. J Geodyn 59–60:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2012.03.003

Kusche J, Eicker A, Forootan E, Springer A, Longuevergne L (2016) Mapping probabilities of extreme continental water storage changes from space gravimetry. Geophys Res Lett. doi:10.1002/2016GL069538

Long D, Longuevergne L, Scanlon BR (2014) Uncertainty in evapotranspiration from land surface modeling, remote sensing, and GRACE satellites. Water Resour Res 50:1131–1151. doi:10.1002/2013WR014581

Long D, Yang Y, Wada Y, Hong Y, Liang W, Chen Y, Yong B, Hou A, Wei J, Chen L (2015) Deriving scaling factors using a global hydrological model to restore GRACE total water storage changes for China’s Yangtze River Basin. Remote Sens Environ 168:177–193. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2015.07.003

Longuevergne L, Wilson CR, Scanlon BR, Crétaux J-F (2012) GRACE water storage estimates for the Middle East and other regions with signficant reservoir and lake storage. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci Discuss 9:11131–11159. doi:10.5194/hessd-9-11131-2012

Lorenz C, Kunstmann H (2012) The hydrological cycle in three state-of-the-art reanalyses: intercomparison and performance analysis. J Hydrometeorol 13:1397–1420. doi:10.1175/JHM-D-11-088.1

Madani K (2014) Water management in Iran: what is causing the looming crisis? J Environ Stud Sci. doi:10.1007/s13412-014-0182-z

Martin-Vide J, Lopez-Bustins J-A (2006) The Western Mediterranean Oscillation and rainfall in the Iberian Peninsula. Int J Climatol 26:1455–1475. doi:10.1002/joc.1388

Moron V, Vautard R, Ghil M (1998) Trends, interdecadal and interannual oscillations in global sea surface temperatures. Clim Dyn 14:545–569. doi:10.1007/s003820050241

Moore P, Williams SDP (2014) Integration of altimetric lake levels and GRACE gravimetry over Africa: inferences for terrestrial water storage change 2003–2011. Water Resour Res 50:9696–9720. doi:10.1002/2014WR015506

Mulder G, Olsthoorn TN, Al-Manmi DAMA, Schrama EJO, Smidt EH (2015) Identifying water mass depletion in northern Iraq observed by GRACE. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 19(3):1487–1500. doi:10.5194/hess-19-1487-2015

Nazemosadat MJ, Cordery I (2000) On the relationships between ENSO and autumn rainfall in Iran. Int J Climatol 20:47–61. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0088(200001)20:1<47::AID-JOC461>3.0.CO;2-P

Oveisi B, Lavé J, Van Der Beek P, Carcaillet J, Benedetti L, Aubourg C (2009) Thick- and thin-skinned deformation rates in the central Zagros simple folded zone (Iran) indicated by displacement of geomorphic surfaces. Geophys J Int 176(2):627–654. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2008.04002.x

Richey AS, Thomas BF, Lo M-H, Reager JT, Famiglietti JS, Voss K, Swenson S, Rodell M (2015) Quantifying renewable groundwater stress with GRACE. Water Resour Res 51:5217–5238. doi:10.1002/2015WR017349

Reichle RH, Koster RD, De Lannoy GJ, Forman BA, Liu Q, Mahanama SP, Touré A (2011) Assessment and enhancement of MERRA land surface hydrology estimates. J Clim 24(24):6322–6338. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-10-05033.1

Rienecker MM et al (2011) MERRA: NASA’s modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications. J Clim 24:3624–3648. doi:10.1175/jcli-d-11-00015.1

Rodell M, Famiglietti JS, Chen J, Seneviratne SI, Viterbo P, Holl S, Wilson CR (2004a) Basin scale estimates of evapotranspiration sing GRACE and other observations. Geophys Res Lett 31:L20504. doi:10.1029/2004GL020873

Rodell M, Houser PR, Jambor U, Gottschalck J, Mitchell K, Meng C-J et al (2004b) The global land data assimilation system. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 85:381–394. doi:10.1175/BAMS-85-3-381

Rogers JC (1984) The association between the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Southern Oscillation in the northern hemisphere. Mon Weather Rev 112:1999–2015. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1984)112<1999:TABTNA>2.0.CO;2

Sabziparvar AA, Mirmasoudi SH, Tabari H, Nazemosadat MJ, Maryanajic Z (2010) ENSO teleconnection impacts on reference evapotraspiration variability in some warm climates of Iran. Int J Climatol 31(6):1710–1723. doi:10.1002/joc.2187

Sakumura C, Bettadpur S, Bruinsma S (2014) Ensemble prediction and intercomparison analysis of GRACE time-variable gravity field models. Geophys Res Lett 41:1389–1397. doi:10.1002/2013GL058632

Scanlon BR, Zhang Z, Reedy RC, Pool DR, Save H, Long D, Chen J, Wolock DM, Conway BD, Winester D (2015) Hydrologic implications of GRACE satellite data in the Colorado River Basin. Water Resour Res 51:9891–9903. doi:10.1002/2015WR018090

Schumacher M, Kusche J, Döll P (2016) A systematic impact assessment of GRACE error correlation on data assimilation in hydrological models. J Geod 90:537. doi:10.1007/s00190-016-0892-y

Swenson S, Wahr J (2009) Monitoring the water balance of Lake Victoria. East Africa from space. J Hydrol 370:163–176. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.03.008

Simmons AJ, Willett KM, Jones PD, Thorne PW, Dee DP (2010) Low-frequency variations in surface atmospheric humidity, temperature, and precipitation: inferences from reanalyses and monthly gridded observational data sets. J Geophys Res 115:D01110. doi:10.1029/2009JD012442

Swenson S, Wahr J (2006) Post-processing removal of correlated errors in GRACE data. Geophys Res Lett 33:L08402. doi:10.1029/2005GL025285

Swenson S, Chambers D, Wahr J (2008) Estimating geocenter variations from a combination of GRACE and ocean model output. J Geophys Res 113:B08410. doi:10.1029/2007JB005338

Tabari H, Abghari H, Hosseinzadeh Talaee P (2014) Impact of the North Atlantic Oscillation on streamflow in Western Iran. Hydrol Process 28:4411–4418. doi:10.1002/hyp.9960

Tapley BD, Bettadpur S, Watkins M, Reigber C (2004) The gravity recovery and climate experiment: mission overview and early results. Geophys Res Lett 31:L09607. doi:10.1029/2004GL019920

Tourian MJ, Elmi O, Chen Q, Devaraju B, Roohi Sh, Sneeuw N (2015) A spaceborne multisensor approach to monitor the desiccation of Lake Urmia in Iran. Remote Sens Environ 156:49–360. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2014.10.006

Trenberth KE (1990) Recent observed interdecadal climate changes in the Northern Hemisphere. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 71:988–993. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1990)071b0988:ROICCIN2.0.CO;2

Trigo RM, Gouveia CM, Barriopedro D (2010) The intense 2007–2009 drought in the Fertile Crescent: impact and associatedatmospheric circulation. Agric For Meteorol 150:1245–1257. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2010.05.006

Turkes M, Erlat E (2003) Precipitation changes and variability in Turkey linked to the North Atlantic Oscillation during the period 1930–2000. Int J Climatol 23:1771–1796. doi:10.1002/joc.962

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2003) Water scarcity in the Middle East-North African region. General Assembly Resolution 53-21, 20 January 2003

Voss KA, Famiglietti JS, Lo M, de Linage C, Rodell M, Swenson SC (2013) Ground water depletion in the Middle East from GRACE with implications for transboundary water management in the Tigris–Euphrates-Western Iran region. Water Resour Res 49:904–914. doi:10.1002/wrcr.20078

Wahr J, Molenaar M, Bryan F (1998) Time variability of the Earth’s gravity field: hydrological and oceanic effects and their possible detection using GRACE. J Geophys Res 103(B12):30205–30229. doi:10.1029/98JB02844

Wang H, Wu P, Wang Z (2006) An approach for spherical harmonic analysis of nonsmooth data. Comput Geosci 32(10):1654–68. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2006.03.004

Wouters B, Bonin JA, Chambers DP, Riva REM, Sasgen I, Wahr J (2014) GRACE, time-varying gravity, Earth system dynamics and climate change. Rep Progr Phys 77(11):116801. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/77/11/116801

Zahid M, Iqbal W, Rasul G, Park KW, Yang H (2014) CMIP5 projected soil moisture changes over South Asia. Pak J Meteorol 10 (20): 13–24. http://www.pmd.gov.pk/rnd/rndweb/rnd_new/journal/vol10_issue20_files/2.pdf. Accessed July 2016

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Michael J. Rycroft (EIC) and two anonymous reviewers whose comments considerably improved the quality of this study. We acknowledge the efforts of providers of GRACE, GLDAS, ERA-Interim, MERRA-Land, and altimetry products, as well as climate indices.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Temporal correlation coefficients are computed between the gridded TWF time series from GRACE and reanalysis products. Our results indicate high (mostly bigger than 0.6) correlation coefficients (at 95% confidence level, Fig. 9) between different products. Some regions with very low correlation coefficients are also detected and are shown in blue (Fig. 9). Interpreting this inconsistency requires further research. In Fig. 10, we show the bi-plot comparisons of TWF changes over the seven basins. The results indicate high agreement between GRACE and reanalysis TWF estimations over Urmia (89%), Tigris–Euphrates and Persian (87%), and Khazar (76%). Slightly worse correspondences are found over the other basins as Sarakhs (67%), Markazi (58%), and Hamun (43%). The last three basins are relatively drier than the first four basins with higher correspondence except Persian whose area is a bigger than the other river basins. As expected, comparisons between TWF derived from GRACE and MERRA-Land results in smaller correlations in most of the basins as over Urmia (64%), Tigris–Euphrates (53%), Persian (78%), Khazar (36%), Sarakhs (61%), Markazi (40%), and Hamun (29%). The bi-plots (of GRACE and MERRA-Land) are not shown here.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Forootan, E., Safari, A., Mostafaie, A. et al. Large-Scale Total Water Storage and Water Flux Changes over the Arid and Semiarid Parts of the Middle East from GRACE and Reanalysis Products. Surv Geophys 38, 591–615 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-016-9403-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-016-9403-1