Abstract

Watershed development initiatives have emerged as key tools for achieving sustainable rural development, especially in countries experiencing environmental degradation and resource constraints. Despite the increasing acknowledgment of the significance of watershed development interventions, there remains a dearth of comprehensive frameworks for evaluating their effects on the socioeconomic progress of communities, particularly concerning rural livelihoods and household food security outcomes. Hence, this study addresses this gap by developing a comprehensive impact analysis conceptual framework tailored to assess the impact of watershed development on socioeconomic aspects. This study designed the framework by incorporating existing theoretical perspectives (the sustainable livelihoods framework, political ecology, theory of change, and community-based natural resource management) and making essential adjustments. This novel conceptual framework offers a multifaceted approach to assess the socioeconomic impacts of watershed development projects, particularly on rural livelihoods and household food security. Employing a mixed methods approach, the framework sheds light on how interventions affect the livelihood assets and strategies of rural communities, ultimately influencing their food security and well-being. Furthermore, it examines how community involvement and national policy affect these efforts. By providing a holistic understanding of watershed development dynamics, this framework allows researchers and practitioners to assess impacts, identify trade-offs, and evaluate interventions. This informs policymakers about evidence-based interventions to promote sustainable socioeconomic development in rural communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Watershed development initiatives have emerged as critical strategies for promoting sustainable rural development, particularly in developing countries facing environmental degradation and resource scarcity (Darghouth et al., 2008). These initiatives encompass a range of activities aimed at improving the health and functionality of watersheds, including soil and water conservation practices, sustainable land management approaches, and the development of water resource infrastructure (Srivastava et al., 2021; Wani & Garg, 2009). By addressing these challenges, watershed development programs hold immense potential to improve the livelihoods and well-being of rural communities that rely heavily on the health of these ecosystems (Hassan, 2008; Perez & Tschinkel, 2003; Siraw et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016; Wani et al., 2008).

A substantial body of research exists on watershed development and management, particularly in the context of developing countries facing environmental degradation and promoting sustainable development. This is especially true in regions such as Ethiopia, where agriculture is the dominant livelihood and communities rely heavily on the health of their watersheds (Aredo, 2011; Bantider et al., 2019; Blaikie, 2016; Gashaw, 2015; Gobena et al., 2024; Herrera et al., 2017; Mukerjee, 2006; Perez & Tschinkel, 2003). However, there remains a notable gap in comprehensively assessing and measuring the true impact of these interventions on the socioeconomic development of communities. The true impact of watershed development initiatives can only be determined through evaluation. Evaluation is a rigorous and objective process that employs established criteria to assess a program’s effectiveness. Essentially, it provides answers about a program’s design, implementation, and the benefits it delivers (Oakley et al., 1998).

Impact analysis theory provides a robust framework for evaluating the consequences of interventions, programs, and policies, such as watershed development and management. It uses different methods to assess both the intended and unintended social, economic, and environmental effects of these interventions. One key question in impact analysis is “What is the true impact (causal effect) of the program on the desired outcome?” This evaluation often uses a “treatment effect” approach, in which two groups are compared: (a) The treatment group, which is directly involved in the program, and (b) The comparison group, which is not involved in the program (Heckman & Vytlacil, 2005; Mishra & Das, 2017). By comparing these groups, researchers aim to isolate the true impact of the program on the outcomes being measured. A critical concept in impact analysis is the “counterfactual.” This concept, introduced by (Pawson & Tilley, 1997), asks the crucial question: “What would have happened if the intervention hadn’t been implemented?” By comparing the observed outcomes with this hypothetical scenario, researchers can isolate the program’s true impact.

To effectively assess the complex impacts of watershed development initiatives, a comprehensive framework is necessary. Traditional impact analysis tools struggle to capture the full picture of complex projects such as watershed development. This research proposes a comprehensive framework that addresses this limitation and introduces a novel framework that integrates the core principles of integrated watershed management and agricultural land resource management. This framework takes a multidisciplinary approach, considering essential social and economic factors. Furthermore, it is designed to align with existing policy frameworks and support structures, ensuring its practical application.

The comprehensive impact analysis framework acts as a single, unified structure for evaluating the process and outcomes of watershed initiatives. It accomplishes this by integrating key elements from existing frameworks: the theory of change, the sustainable livelihood framework, political ecology, and community-based natural resource management principles. This comprehensive approach ensures a holistic analysis of watershed development projects, fostering sustainable outcomes and empowering local communities.

The theory of change framework is a cornerstone of rigorous impact analysis and serves as a roadmap, outlining the causal pathway through which a program or intervention is expected to achieve its objectives. It clarifies the causal pathway of the project’s impact. This framework allows for a more focused and rigorous assessment of whether the program is truly achieving its intended objectives (Connell & Kubisch, 1998; Weiss, 1997). The sustainable livelihood framework is another powerful tool used in impact analysis, particularly when evaluating interventions aimed at improving the well-being of rural communities. It identifies and measures the impacts on key livelihood assets. It emphasizes the importance of assessing the impact of interventions on various livelihood assets that contribute to a community’s overall well-being (Scoones, 1998).

Political ecology offers a valuable lens for a more nuanced understanding, let alone for measuring the technical effectiveness and economic outcomes of interventions. It examines the complex relationships between environmental issues, social structures, and power dynamics. The incorporation of this perspective into impact analysis encourages the participation of diverse stakeholders in impact analysis, ensuring that their voices and concerns are heard (Robbins, 2019; Springate-Baginski & Blaikie, 2013). The integration of community-based natural resource management principles promotes community participation, user rights, and equitable benefit sharing through the use of established impact analysis methods. Although it is not a complete evaluation framework, it serves as a powerful lens for analyzing these interventions (Agrawal & Gibson, 2001; Brosius et al., 1998).

Combining frameworks in impact analysis unlocks a deeper understanding (Almalki, 2016; Bennett & Hammer, 2017; Cash et al., 2003; Glaser & Strauss, 2017), especially for developmental interventions in rural communities. This study emphasizes the value of building a comprehensive framework for a more nuanced evaluation (Jabbour et al., 2019). By integrating the theory of change with the sustainable livelihoods framework, researchers can not only assess a project’s effectiveness but also understand how it influences various livelihood assets crucial for long-term well-being. Furthermore, incorporating the principles of political ecology ensures a socially just approach by considering power dynamics, potential environmental consequences, and the experiences of marginalized groups. Finally, integrating community-based natural resource management principles places the community at the center, fostering participation, equitable benefit sharing, and a deeper understanding of the project’s true impact on both the environment and the people who depend on it. This multifaceted approach to impact analysis goes beyond measuring technical successes to promote social justice, empower local communities, and ensure that interventions contribute to truly sustainable development.

Methodology

This section outlines the research methodology employed to construct the framework. It details the underlying philosophical assumptions (research philosophy), the chosen research strategy, and the specific approaches and techniques used for each research component. The well-established Research Onion framework (Saunders & Aragón-Zavala, 2007; Saunders et al., 2009) was adopted due to its versatility and applicability across various research methodologies and contexts (Bell et al., 2022). This (Fig. 1) framework was then adapted to suit the specific requirements of this investigation.

The framework was constructed using a mixed-methods approach (Agresti & Finlay, 2009; Clark & Creswell, 2008; Creswell, 2021; Creswell & Creswell, 2005; Kothari, 2004), drawing upon both literature-based and existing framework analyses. This study involved a comprehensive review of primary and secondary sources relevant to watershed development impact assessment. Drawing from a systematic literature review, this study gleaned valuable insights into the multifaceted aspects of watershed development and its potential socioeconomic outputs, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative studies. The search strategy used in this study included the use of academic databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, as well as gray literature sources such as reports from government agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international development organizations. The keywords used in the search included “watershed management,” “livelihoods,” “socioeconomic impacts,” “watershed development,” “food security,” “community participation,” “policy analysis,” “developing countries,” and “Ethiopia.” The inclusion criteria for studies included empirical research, policy analyses, and theoretical frameworks relevant to watershed development and management. Additionally, theoretical frameworks and conceptual papers were included to provide theoretical insights into the dynamics of watershed management.

Thematic analysis was then employed to identify key components within these data sources and explore the relationships between them, ultimately informing the development of the framework. This study followed a three-step process to construct a comprehensive framework for analyzing the impact of watershed development on socioeconomic development. First, a thorough review of the literature and relevant theories laid the groundwork. This initial stage was crucial, as integrating insights from established research, theoretical foundations, and practical experiences is essential for designing an effective framework. Building upon this foundation, the research then progressed to constructing the actual framework components by drawing on the identified theories and principles. Finally, the culmination of the research resulted in a fully developed framework, complete with a practical guide for applying it in real-world contexts.

Theoretical perspectives

This section establishes the groundwork by reviewing the literature on the theoretical perspectives of watershed development and management. The term watershed combines two words: water and shed. Water exists in nature as solid, liquid, or vapor. In a watershed, water is primarily considered in its liquid form. The term “shed” refers to the roof of a building that collects rainwater and directs it away. In this context, a shed represents an area clearly defined by boundaries where rainwater gathers and flows toward a common drainage point or outlet. Watersheds, also known as catchments or drainage basins, are topographic regions where surface and shallow groundwater converge to a specific location (Griffith et al., 1999; Omernik & Bailey, 1997).

The precise definitions of watershed development and watershed management remain elusive in the literature, leading to their frequent interchangeability in various studies. In this context, this study clarifies the following distinctions: watershed development, defined as programs involving targeted technical interventions, such as afforestation, construction of check dams, and soil conservation practices. These interventions aim to enhance the productivity of specific natural resources within the watershed, with the objective of optimizing resource utilization while ensuring sustainable water availability (Abbaspour et al., 2007; Kerr, 2007; Wang et al., 2016). On the other hand, the term watershed management refers to the holistic understanding and regulation of hydrological relationships within a watershed. Rather than solely investing in physical interventions, socioeconomic and ecological factors are considered. The emphasis is on safeguarding resources from degradation, with the objective of maintaining ecological balance, preventing resource depletion, and promoting sustainable livelihoods (France, 2006; Wang et al., 2016; Wani et al., 2011). Recognizing the interdependence between technical interventions and subsequent management efforts, our study adopts an integrated approach. This study employs the combined term “watershed development and management” to underscore the necessity of integrating both ecological and socioeconomic aspects for effective watershed governance.

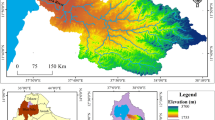

Research on watersheds can be categorized into three distinct perspectives (see Fig. 2): engineering-focused, scientific, and study-oriented (Batey & Kim, 2021; FAO, 2006). From an engineering perspective, studies have focused on technical and engineering challenges related to watershed management (Wang & Yang, 2014; Zhang & Tang, 2010). The second perspective emphasis on scientific approaches revolves around methods (Allanson et al., 2012; Dingman, 2015; Razavi et al., 2020; Usman, 2018; Vörösmarty et al., 2000). The “Studies” domain encompasses various disciplines, such as the social sciences, economics, and policy, that contribute to comprehensive watershed management strategies(Pahl-Wostl, 2009). The perspective of these studies explores the socioeconomic aspects of watershed management. This perspective acknowledges the human element and integrates social, economic, and political factors influencing water resource management within a watershed. Concepts such as governance structures, institutional arrangements, and community participation come into play in the field of watershed management (Lebel et al., 2006; Woodhouse & Muller, 2017). This study aligns with this third viewpoint by examining the socioeconomic dimensions of watershed management practices.

Three empirical categories of watershed management adapted from (Batey & Kim, 2021)

Theoretical foundation

Building upon the established knowledge base, this section delves into relevant theories that link watershed development to socioeconomic development. Frameworks such as the theory of change (ToC), the sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF), political ecology, and community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) are included. The discussion explores how these theories can inform the comprehensive impact analysis framework’s design, identifying key concepts and relationships that will be incorporated into the final structure.

Sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF)

The concept of livelihoods emerged in the mid-1980s, and since then, several development agencies have integrated into their poverty reduction policies and programs. Livelihood encompasses the skills, resources (both material and social), and necessary activities for a means of living (Chambers & Conway, 1992). Livelihood analysis focuses on understanding how individuals earn a living within specific contexts. In most societies, households serve as fundamental productive and reproductive units, making the study of household economics central to livelihood analysis. The sustainable livelihoods framework (SLF) is one of the prominent frameworks used to analyze livelihoods. The SLF was initially developed by the UK Department for international development (DfID) in the late 1990s and offers a multidimensional approach to assessing and enhancing livelihoods in rural contexts (U. J. L. D. DfID, 1999a, 1999b).

The SLF is a framework that enhances our understanding of how poor and vulnerable populations sustain their livelihoods. It identifies five key livelihood assets and examines how their interactions shape livelihood outcomes. This highlights the significance of integrating various assets to achieve successful livelihood outcomes (Baffoe & Matsuda, 2018; Bebbington, 1999; Ellis, 2000; Scoones, 2009). Key theoretical foundations within the SLF provide valuable insights into understanding the complex interactions between watershed interventions, rural livelihoods, and household food security (Chambers & Conway, 1992; U. J. L. D. DfID, 1999a, 1999b).

Political ecology

Political ecology examines the political-economic factors that shape environmental governance, resource distribution, and access to decision-making processes (Robbins, 2019). It emphasizes the inherent “politicalness” of the environment, arguing that environmental degradation cannot be solely understood through scientific and technical lenses (Peet & Watts, 2004). A core principle is the unequal distribution of power and influence over environmental resources. Political ecology highlights how powerful actors, such as corporations or governments, often prioritize economic gain over environmental sustainability, disproportionately impacting marginalized communities (Blaikie & Brookfield, 2015).

Political ecology extends its analysis beyond environmental issues to encompass the influence of institutions and governance structures on resource management outcomes. This aligns with Elinor Ostrom’s (1990) seminal work on common pool resources, which emphasizes the critical role of local institutions and community-based governance mechanisms in achieving sustainable resource use (Ostrom, 1990). Fikret Berkes (2009) further exemplifies this perspective in the context of watershed development, arguing that successful projects hinge on the active participation of local communities in decision-making processes and the recognition of their customary resource management practices (Berkes, 2009). Political ecology emphasizes the interconnectedness of social and ecological systems. Human societies are not separate from the environment but coevolve with it. Decisions made within a society can have lasting ecological consequences(Robbins, 2019).

The interdisciplinary nature of political ecology makes it a valuable tool for understanding complex environmental challenges and offers a valuable theoretical foundation for designing a conceptual framework to analyze the impact of watershed development and management. This perspective recognizes that environmental change and resource management are deeply intertwined with political and economic processes, power dynamics, and social inequalities (Forsyth, 2004). By incorporating political ecology into the conceptual framework, one can analyze how watershed development interventions are influenced by broader political and institutional dynamics, including government policies and programs. This perspective helps in identifying potential barriers to equitable participation and benefit sharing in watershed projects, as well as implications for social justice and environmental sustainability.

Theory of change (ToC)

This section explores the theoretical foundations of the ToC in the context of watershed development, drawing upon relevant literature and citations. ToC provides a theoretical foundation that helps in identifying the causal pathways through which watershed management activities influence rural livelihoods and household food security. The theory of change is a conceptual framework that delineates the sequence of intermediate outcomes and causal pathways required to achieve long-term goals. It helps in articulating the underlying assumptions about how interventions are expected to bring about change and provides a roadmap for program planning, implementation, and evaluation. It emphasizes the importance of clarifying the logic of intervention and specifying the mechanisms through which change is expected to occur (Connell & Kubisch, 1998). ToC provides a structured approach to understanding causal pathways and intervention points for achieving desired outcomes in complex development initiatives. Within the context of watershed management, ToC frameworks help identify key inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts, as well as underlying assumptions and contextual factors influencing project success (Muthle, 2021).

ToC is particularly relevant for evaluating the effectiveness and sustainability of watershed development projects. By specifying the causal pathways and intermediate outcomes, the ToC facilitates the identification of key performance indicators and evaluation metrics. It allows for the systematic tracking of progress along the intervention pathway and helps in assessing whether the expected changes are occurring as anticipated (Valters, 2014). Moreover, ToC encourages stakeholders to engage in reflective learning and adaptive management, enabling interventions to be adjusted based on emerging evidence and insights (Mayne, 2015).

By integrating the ToC into the conceptual framework, researchers can develop explicit hypotheses about the mechanisms through which watershed development interventions impact rural livelihoods and household food security. This perspective facilitates the design of monitoring and evaluation frameworks that track progress toward intended outcomes and allow for adaptive management based on empirical evidence (De Silva et al., 2014). By integrating a ToC in the livelihood framework, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners can deepen their understanding of how watershed management initiatives positively impact rural communities. This framework illuminates the causal pathways by which these initiatives, implemented in natural resource-dependent regions, ultimately contribute to improved livelihoods and household food security. For instance, this study proposes utilizing a ToC framework to evaluate how watershed interventions affect livelihoods. The ToC elucidates the connection between specific watershed development practices (such as soil conservation) and ecological enhancements (such as increased water availability), ultimately benefiting local communities (e.g., improved food security). It provides a strategic framework for identifying causal pathways and intervention points to achieve desired outcomes in watershed management (Vogel et al., 2012).

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)

Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) is a people-centered approach that emphasizes the importance of participating local communities in the management and conservation of natural resources to overcome poverty, hunger, and disease (Fabricius, 2013; Leach et al., 1999). It aims to balance conservation and development by empowering communities to make decisions about their resources (Berkes, 2007). CBNRM emerged in the early 1980s as an alternative to perceived failing resource regimes (Gibson & Marks, 1995). In recent years, CBNRM has gained significant prominence as an approach for studying natural conservation and socioeconomic objectives. It aims to harmonize conservation, sustainable development, and community engagement (Boggs, 2000).

CBNRM is a dynamic approach that empowers local communities to actively engage in managing natural resources (Wasonga et al., 2010). This is achieved through several fundamental principles. First, the devolution of decision-making power from central authorities to local communities ensures that resource management aligns with community needs and aspirations. Second, CBNRM emphasizes local participation, encouraging communities to take ownership of their natural assets. Third, the incorporation of traditional knowledge enriches management practices, drawing on centuries-old wisdom to inform sustainable resource use. Finally, CBNRM strikes a delicate balance between conservation and livelihoods, recognizing that both people and ecosystems benefit from responsible resource utilization (Berkes, 2007; Jones, 2004; Milupi et al., 2017; Wasonga et al., 2010). By empowering communities to participate in decision-making processes related to watershed management, CBNRM fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility among community members, thereby enhancing their capacity to address food security challenges.

Incorporating CBNRM principles into the conceptual framework for watershed development requires a multilevel governance strategy. This approach acknowledges the interconnections between socioecological systems and emphasizes community participation, local knowledge systems, and traditional resource management practices. These elements are pivotal in enhancing adaptive capacity, fostering social learning, and encouraging collective action among various stakeholders. As a result, they contribute to more effective and sustainable outcomes in watershed management, ensuring both sustainable food production and livelihoods within these regions (Ostrom, 1990).

Results and discussions

Framework development

Based on the findings from the theoretical perspective and exploration, this study identifies four key components for its framework: watershed development practices (Watershed Initiatives), socioeconomic indicators (Livelihood Outcomes), impact pathways (Livelihood Assets) and contextual factors (Livelihood Strategies, Vulnerability Context, Policies and Institutions, and Level of Community Participation).

Watershed development practices

This section of the framework will identify the essential components of watershed development activities implemented within a particular watershed. For the purposes of this study, the term “watershed initiatives” will be used to refer to these activities.

Watershed initiatives

At the core of the framework lies the management of natural resources within the watershed, including soil, water, vegetation, and biodiversity. Watershed development activities such as soil conservation, water harvesting, afforestation, and sustainable agricultural practices directly influence the availability and quality of these resources. This study assessed the following practices: soil and stone bunds, fanyajuu bunds, gully rehabilitation with check dams, drainage ditches, cutoff drains, grass/shrubs/strips, agroforestry, area closure, composting, legume‒cereal crop rotation, and intercropping. The sustainable management of natural resources is essential for maintaining ecosystem services that support agricultural productivity, water availability, and biodiversity conservation. For instance, watershed development initiatives may improve natural capital through soil and water conservation measures, thereby enhancing agricultural productivity and income generation opportunities for rural households.

Socioeconomic indicators

This component of the framework focuses on defining the specific dimensions of community well-being that will be employed to measure the impact of watershed development programs. These dimensions will encompass various livelihood outcomes.

Livelihood outcomes

Watershed development initiatives have significant socioeconomic impacts on local communities (Reddy & Soussan, 2004). The sustainable livelihoods approach emphasizes the importance of enhancing assets and capabilities to improve household food security and well-being (Carney, 1998). In this framework, livelihood outcomes encompass income and employment generation, agricultural productivity, social service and infrastructure, and food security (Kassegn & Endris, 2021; Marchang, 2018; Mfunda & Roskaft, 2011). The study specifically focuses on these outcomes and does not consider other factors beyond its defined scope. The framework connects food security dimensions (availability, utilization, stability, and access) with other livelihood aspects. Food security, as conceptualized in sustainable livelihoods, plays a crucial role in shaping a household’s overall well-being and livelihood dynamics (Gladwin et al., 2001; Sutherland et al., 1999). It outlines the factors and interdependencies that influence a household’s food security and livelihood conditions.

Impact pathways

This component of the framework explores the causal relationships between watershed initiatives and the selected socioeconomic indicators, particularly focusing on livelihood assets. It aims to establish a clear understanding of how these activities influence various aspects of community well-being.

Livelihood assets

In the framework, livelihood assets include those capabilities, assets, and activities required for a means of living (Hussein, 2002; Natarajan et al., 2022). The framework identifies five core assets that constitute the foundation of rural livelihoods: human assets, social assets, natural assets, physical assets, and financial assets (U. DfID, 1999a, 1999b). The sustainable livelihoods framework offers a comprehensive analytical tool for assessing the vulnerability and resilience of rural households to environmental and socioeconomic changes (Scoones, 1998). Research by (Ellis, 2000) emphasizes the significance of assets in shaping rural livelihoods. These assets represented by pentagons show households’ differential access to assets and dynamically impact household well-being and resilience (U. J. L. D. DfID, 1999a, 1999b; Karki, 2021). By integrating livelihood assets into the conceptual framework, we gain a comprehensive understanding of how watershed development interventions impact these assets and, consequently, influence rural livelihood outcomes. For example, natural capital—comprising land and water resources—plays a crucial role in agricultural production and food security (Scoones, 1998).

Contextual factors

This framework acknowledges the influence of external factors on the nexus between watershed development initiatives and socioeconomic outcomes. To address this, the framework incorporates considerations of livelihood strategies, vulnerability context, policies and institutions, and the level of community participation.

Livelihood strategies

The framework recognizes that households employ diverse livelihood strategies to cope with uncertainties and meet their needs (U. DfID, 1999a, 1999b). Research highlights the dynamic nature of livelihood strategies and the importance of understanding their linkages with broader development interventions (Ellis & Allison, 2004; Liu et al., 2018). By integrating livelihood strategies into the conceptual framework, researchers can analyze how watershed development influences the choice and effectiveness of livelihood strategies adopted by rural households. Moreover, the framework allows for the assessment of how changes in livelihood strategies translate into various outcomes, including income and employment generation, agricultural productivity, social service and infrastructure, and food security.

Vulnerability context

The SLF emphasizes the significance of considering the broader socioeconomic and environmental context in which livelihoods are situated (U. DfID, 1999a, 1999b). This includes factors that shape vulnerability and resilience within communities. (Adger, 1999) highlighted the importance of understanding socioeconomic vulnerabilities to environmental change in rural areas. By incorporating this aspect into the conceptual framework, researchers can analyze how watershed development interacts with existing vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities within communities. For instance, (Bhatta et al., 2019) found that watershed development projects in the Himalayan River Basin in Nepal contributed to reducing vulnerability to climate change impacts by improving water management practices and enhancing agricultural productivity. The framework included the biophysical and socioeconomic drivers of trends, shocks, and seasons.

Policies and institutions

Effective legal frameworks, thoughtfully crafted policies, efficiently organized institutions, and streamlined procedures are critical for steering watershed development efforts. These elements offer the necessary institutional support and regulatory mechanisms, ultimately ensuring the success of watershed development initiatives (UN, 2008). A country’s policies and strategies related to natural resource conservation, particularly in the context of watershed management and development, profoundly affect asset availability, which in turn impacts household livelihood outcomes (Rakodi, 1999).

The framework considers the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders, including government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, community-based organizations, and local communities. It examines the institutional capacity, coordination mechanisms, decision-making processes, and resource allocation mechanisms that govern watershed management activities. The conceptual framework enables an exploration of how policy- and strategy-related factors impact resource access and control, influence decision-making, and mediate the distribution of benefits and costs related to natural resource management in watershed areas (Blaikie, 2016).

Level of community participation

Community participation is a key determinant of the success and sustainability of watershed development initiatives. The level of participation refers to the extent to which households participate in watershed development initiatives. The framework emphasizes the importance of engaging local communities in all stages of project planning, implementation, and monitoring. It examines the level of community participation, the inclusiveness of decision-making processes, and the empowerment of marginalized groups, including women and indigenous communities. This framework conceptualizes a household’s level of participation as the willingness of a household to use its assets or capital to participate in watershed development initiatives.

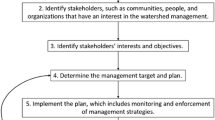

Framework application

Building upon the framework outlined in Fig. 3, this section delves into two key aspects. First, it explores the methodologies and practices employed within the framework in general and at the component level. This exploration includes the practical application of these methods in analyzing the impact of watershed development initiatives. Second, the section examines the pathways or implementation stages of the framework.

Methods to apply the framework

This section explores practices and methodologies for data collection to analyze the impact of watershed development on the framework. Furthermore, data collection instruments and data analysis techniques specifically designed for the various components within the framework are discussed.

To operationalize the proposed comprehensive impact analysis framework within a specific watershed community, a mixed-method approach is recommended. The framework utilized a cross-sectional survey to gather information. The following section outlines the data collection methods and techniques that are tailored to the framework. To achieve a comprehensive understanding, triangulating primary and secondary data sources are needed. Primary data collection relied on various techniques to capture diverse perspectives within the sampled watersheds. Household surveys (HSs) using structured questionnaires needed to be administered to household heads, providing a quantitative assessment of the situation. Key informant interviews (KIIs) with local leaders, elders, youth representatives, and women offered valuable insights from community members with distinct experiences. Focus group discussions (FGDs) facilitated in-depth exploration of specific topics with a targeted group, fostering a more nuanced understanding. Additionally, the researcher needs to employ personal participant observation, directly engage with the community and document their activities. This multifaceted approach to data collection ensured a rich and well-rounded understanding of the research subjects within the watershed community. Secondary data, including watershed development laws for a given country, project reports, program documents and government publications examining the evolution, achievements, and existing gaps in management practices, complemented the primary data and provided historical context and broader perspectives at the country level.

To demonstrate the practicality of the framework in Ethiopia, (Argaw et al., 2023; Naji et al., 2023, 2024) employed a mixed-methods approach. A structured questionnaire survey was administered to 312 household heads selected through multistage sampling. KIIs and FGDs were conducted with a total of 71 participants purposively selected based on their knowledge and experience with watershed development. These participants included community members (leaders, elders, youth, and women), watershed development experts, government officials, and policymakers. The researcher applied a guided transect walk and conducted a thorough document analysis.

Recognizing the need for a comprehensive assessment of watershed development initiatives, this framework goes beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, it proposes a suite of specifically designed data collection and analysis tools tailored to each of its key components. These components are thematically categorized as follows: assessment of watershed development practices, measurement of livelihood outcomes, evaluation of community participation levels, and analysis of policies and institutions. By employing these tailored tools, the framework facilitates a holistic understanding of the effectiveness and sustainability of watershed development initiatives.

Assessing watershed development practices

This section outlines the key components of watershed development activities implemented within a specific watershed. These components will be analyzed based on data collected through a transect-field walk. During this walk, the researcher documented observations through field notes, photographs, and video recordings. To demonstrate the practicality of the framework in Ethiopia, (Argaw et al., 2023; Naji et al., 2023, 2024) assessed the following practices: soil and stone bunds, fanyajuu bunds, gully rehabilitation with check dams, drainage ditches, cutoff drains, grass/shrubs/strips, agroforestry, area closure, composting, legume‒cereal crop rotation, and intercropping.

Measuring livelihood outcomes

This section of the framework outlines the key components of livelihood outcomes that measure the impact of watershed development programs. Encompassing a broad spectrum of dimensions, these outcomes include income generation, employment creation, agricultural productivity, social services and infrastructure, and food security. To facilitate a more nuanced understanding of program impact during data analysis, the framework divides these outcomes into two distinct categories. The framework’s first category combines income and employment generation, agricultural productivity, and social services and infrastructure. The impact of watershed development programs on these aspects is assessed by measuring changes in household livelihood status. Food security, due to its multifaceted nature, availability, utilization, stability, and access dimensions, is considered a separate category. The impact of watershed development programs on these aspects is assessed by measuring changes in household food security status.

This strategic categorization allows for the application of specific methods and techniques tailored to analyze data within each group, ultimately leading to a more comprehensive evaluation of the program’s influence on community livelihoods. Hereby, the measurement techniques and analysis tools are discussed.

Measuring the livelihood status of households

The framework measures the livelihood status of the household using livelihood assets. Eighteen variables were chosen to represent the five livelihood assets (human, financial, natural, physical, and social) of households within the selected watersheds. These variables were selected based on a review of the relevant literature (Bingen et al., 2003; Chambers & Conway, 1992; U. J. L. D. DfID, 1999a, 1999b; Katz, 2000; Ninan & Lakshmikanthamma, 2001; Rakodi, 1999; Scoones, 1998; Solesbury, 2003) and on-site observations of the livelihood conditions and the role of watershed development practices in the study communities. Human capital is measured by household head age, education level, household size, and available labor force. Financial capital is assessed through annual agricultural and nonagricultural income, livestock holdings, and access to credit. Natural capital is evaluated by considering access to and characteristics of agricultural land, including total area, fertility, and high-quality land ownership. Physical capital is assessed through housing quality, household possessions, access to public transportation, and proximity to markets. Finally, social capital is measured by membership in social organizations, social network strength and harmony, and the presence of local NGOs or institutions. This multifaceted approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the livelihood status of households within the context of watershed management initiatives.

Following the identification of livelihood assets and their corresponding indicators, the framework employs various scaling and indexing methods. Scaling techniques, such as rating scales, ensure data comparability and facilitate meaningful interpretation. Subsequently, a composite measurement index is constructed to represent each livelihood asset. The results of these indices are then visually depicted within the framework’s livelihood asset pentagon, a core component of the sustainable livelihoods framework. To statistically compare livelihood asset levels between treated and untreated watershed areas, nonparametric tests such as the Kruskal‒Wallis test can be employed. (See (Argaw et al., 2023), for a practical example.)

Measuring the relationships and impact of the WDMP on livelihood assets

This framework utilizes structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze the collected data. SEM allows for the investigation of causal relationships between latent (unobserved) and observed (measurable) variables. Statistical software, such as SPSS and Stata, can be used for data management and preliminary analysis. Subsequently, AMOS software facilitates the testing of the hypothesized structural equation model.

An empirical study conducted in Ethiopia (Argaw et al., 2023) demonstrated the practical application of the model. This study employed a model that incorporates forty-nine manifest indicators to capture nine latent variables. These latent variables represent crucial aspects of the system, including watershed development practices, various livelihood outcomes (income and employment generation, agricultural productivity, social services and infrastructure), and the five livelihood capitals (natural, human, physical, financial, and social).

Measuring the relationships and impact of the WDMP on household food security

This section emphasizes measuring household food security status using food insecurity measurement tools and comparatively analyses the impact of watershed development practices. There are diverse food insecurity measurement tools that offer a variety of indicators for assessing and monitoring food security and nutrition. Commonly employed tools include the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS), the Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD-W), the Household Hunger Scale (HHS), the Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP), the Food Consumption Score (FCS), the Prevalence of Moderate or Severe Food Insecurity (FIES), the Prevalence of Undernourishment (PoU), and potentially others. By analyzing data collected through these tools, a given study can utilize any inferential statistics depending on the nature of the data “data type” to identify factors influencing household food security status and examine the impact of WDMPs. For instance, the HFIAS and HDDS scores are likely ordinal data, meaning that they represent categories or levels (e.g., food security, mild insecurity) rather than continuous numerical values; as a result, the study used an ordinal logistic regression method.

An empirical study conducted in Ethiopia (Naji et al., 2024) exemplifies this approach. Their questionnaire was specifically developed by adapting the HFIAS and HDDS tools from the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (FANTA). This demonstrates the practical application of established measurement tools in assessing food security within a specific context. Based on an ordinal logistic regression test, the study revealed a clear difference in food security scores (measured by the HFIAS and HDDS) between those who participated in WDMPs and those who did not.

Measuring the level of community participation

This section addresses the measurement of community participation, a crucial component influencing the sustainability of watershed development initiatives. Questionnaires can be developed to assess participation levels, drawing upon established community-based watershed development guidelines developed by the given country allied with discussions of local elders, local governmental and nongovernmental experts and officials. The People’s Participation Index (PPI) serves as a tool for quantifying household participation throughout the various phases of WDM: planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation. The PPI is a widely applied index (Bagdi & Joshi, 2018; Das, 2022; Mengistu & Assefa, 2020; Mondal et al., 2020; Roba Gamo et al., 2022) developed by (Bagdi et al., 2002). By analyzing data collected through these tools, a given study can utilize any inferential statistics depending on the nature of the data “data type” to identify significant factors that determine households’ level of participation.

The practical application of the PPI is exemplified by a case study conducted in Ethiopia (Naji et al., 2023). This study employed the PPI to assess the level of household participation throughout the various phases of WDM. The development of the questionnaire used to measure participation levels drew upon two key resources. First, the study incorporated the established community-based watershed development guidelines of Ethiopia developed by (Lakew et al., 2005). Second, the questionnaire design was informed by discussions with local stakeholders, including elders, government and nongovernmental officials and experts. Given the ordered nature of the study’s dependent variable (categorized as low, medium, or high participation), an ordinal regression model was employed for the data analysis.

Assessing policies and institutions

This section of the framework addresses the analysis of policies and institutions, recognizing their significant influence on the sustainability of watershed development initiatives. A multifaceted approach is needed to gather data from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data collection leverages the benefits of participant observation, allowing researchers to directly witness policy and institutional practices within the specific watershed context. Additionally, structured or unstructured KIIs and FGDs are utilized. KIIs offer in-depth insights from key stakeholders regarding their perspectives on relevant policies and institutions, while FGDs facilitate group discussions to glean community experiences with these entities. To complement these primary data sources, a meticulous document review was performed. This secondary data collection focuses on official documents from the given country, encompassing proclamations, regulations, policies, strategies, programs, and approaches related to agriculture, water, watershed development and management, irrigation, food security, development, and the environment.

Thematic analysis, a qualitative research method, is well suited for analyzing collected data. This method involves a systematic process of identifying, organizing, and synthesizing key themes and findings from the selected studies. By aligning these themes with the overall research objectives, thematic analysis facilitates a deeper understanding of the research topic. By employing this comprehensive data collection and analysis approach, the framework ensures a thorough evaluation of the policy and institutional environment surrounding watershed development initiatives.

Paths of the framework

By integrating theoretical underpinnings with empirical considerations, this study presents a comprehensive framework for analyzing the impact of watershed development initiatives. This framework sheds light on the complex and interconnected relationships among the multifaceted nature of watershed development, rural livelihood outcomes, and the crucial roles of community participation and policy. This section focuses on the practical application of the framework (see Fig. 4), exploring the specific pathways utilized to assess the impact of watershed development initiatives.

Challenges and limitations of applying the framework

Implementing the framework for watershed development impact analysis may encounter challenges. Gathering the necessary data can be resource intensive, demanding time, personnel, and funding. Furthermore, accessing complete and reliable data from various sources, such as community surveys and government documents, can be difficult, especially in remote areas. Engaging diverse stakeholders, such as community members and local officials, in a meaningful way can also be time-consuming and require careful planning.

Analyzing the collected data also presents hurdles. Combining data from different sources and formats can be complex, requiring robust data management and analysis techniques. Establishing clear cause-and-effect relationships between watershed development activities and specific outcomes can be challenging due to external factors influencing livelihoods. Additionally, the framework’s applicability might be limited in regions with distinct social, ecological, and political characteristics compared to the context for which it was designed.

Beyond data and analysis, implementing the framework presents its own challenges. Local institutions may require capacity building to effectively utilize the framework’s methods and interpret the results. Ensuring ongoing monitoring and evaluation for long-term success can be difficult due to resource constraints and commitment limitations. Finally, translating the framework’s findings into actual policy changes might require additional efforts. Effective communication and advocacy strategies are crucial for influencing policy decisions based on the valuable insights generated by the framework. While these challenges exist, the framework offers a valuable tool for analyzing the impact of watershed development initiatives, and being aware of these limitations allows for better planning and implementation strategies.

Conclusions and recommendations

Despite the increasing acknowledgment of the significance of watershed development interventions in rural development, there remains a dearth of comprehensive frameworks for evaluating their effects on the socioeconomic progress of communities, particularly concerning rural livelihoods and household food security outcomes. Hence, this research introduces a conceptual framework tailored to assess the influence of watershed development on rural livelihoods and household food security at the household level. This study designed the framework by incorporating existing theoretical perspectives and making essential adjustments.

The designed conceptual framework can be applied to assess the impact of watershed development projects on rural livelihoods and household food security through a mixed methods approach. With mixed methods, data can be collected through household surveys, focus group discussions, key informant interviews, participant observation, participatory mapping, and remote sensing techniques. The paths of the framework clearly show the different tasks and pathways within the framework to which to apply. The designed framework highlights the significance of comprehending the mechanisms or paths through which changes unfold over time (U. DfID, 1999a, 1999b). In this context, it offers insights into how interventions can affect the livelihood assets and strategies of rural communities, thereby influencing their food security and well-being. Additionally, it shows the correlation between community participation and livelihood outcomes, as well as the impact of a country’s policies and institutions on watershed development efforts.

Using this framework, researchers and practitioners can explore the impact and analyze the causal pathways through which watershed interventions influence socioeconomic outcomes, identify potential trade-offs and synergies between different objectives, and assess the effectiveness of specific interventions in achieving desired outcomes. Policymakers can use the findings to design more targeted and evidence-based interventions that address the diverse needs and priorities of rural communities.

Data availability

The authors declare that data will be made available on request.

References

Abbaspour, K. C., Yang, J., Maximov, I., Siber, R., Bogner, K., Mieleitner, J., Zobrist, J., & Srinivasan, R. (2007). Modelling hydrology and water quality in the pre-alpine/alpine Thur watershed using SWAT. Journal of Hydrology, 333(2–4), 413–430.

Adger, W. N. (1999). Social vulnerability to climate change and extremes in coastal Vietnam. World Development, 27(2), 249–269.

Agrawal, A., & Gibson, C. C. (2001). Communities and the environment: ethnicity, gender, and the state in community-based conservation. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (2009). Statistical methods for the social sciences.

Allanson, B. R., Hart, R., O’keeffe, J., & Robarts, R. (2012). Inland waters of Southern Africa: an ecological perspective. Springer Science & Business Media., 64, 458.

Almalki, S. (2016). Integrating quantitative and qualitative data in mixed methods research-challenges and benefits. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(3), 288–296.

Aredo, D. (2011). Agricultural Development: Theory, Policy, and Practice. https://books.google.com.et/books?id=q7QlrgEACAAJ〹

Argaw, T., Abi, M., & Abate, E. (2023). The impact of watershed development and management practices on rural livelihoods: A structural equation modeling approach. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 9(1), 2243107.

Baffoe, G., & Matsuda, H. (2018). An empirical assessment of rural livelihood assets from gender perspective: Evidence from Ghana. Sustainability Science, 13(3), 815–828.

Bagdi, G., Samra, J., & Kumar, V. (2002). People’s participation in soil and water conservation programme in Sardar Sarovar Project Catchment.

Bagdi, G., & Joshi, U. (2018). People’s participation in implementation of soil and water conservation programme: Case study of antisar watershed in Kheda district of Gujarat. Indian Journal of Extension Education, 54(4), 74–83.

Bantider, A., Gete Zeleke, G D., Alamirew, T., Alebachew, Z., Providoli, I., & Hurni, H J S S S-E L ., (2019). From land degradation monitoring to landscape transformation: Four decades of learning, innovation and action in Ethiopia. 19.

Batey, P. W., & Kim, J. S. (2021). Special issue on comprehensive watershed management: Sustainability, technology, and policy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 5, 523–530.

Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27(12), 2021–2044.

Bell, E., Bryman, A., & Harley, B. (2022). Business research methods. Oxford University Press.

Bennett, M. J., & Hammer, M. (2017). Developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication, Wiley: Hoboken.

Berkes, F. (2007). Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(39), 15188–15193.

Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(5), 1692–1702.

Bhatta, B., Shrestha, S., Shrestha, P. K., & Talchabhadel, R. (2019). Evaluation and application of a SWAT model to assess the climate change impact on the hydrology of the Himalayan River Basin. CATENA, 181, 104082.

Bingen, J., Serrano, A., & Howard, J. J. F. (2003). Linking farmers to markets: different approaches to human capital development. Food Policy, 28(4), 405–419.

Blaikie, P. (2016). The political economy of soil erosion in developing countries. Routledge.

Blaikie, P., & Brookfield, H. (2015). Land degradation and society. Routledge.

Boggs, L. P. (2000). Community power, participation, conflict and development choice: Community wildlife conservation in the Okavango region of Northern Botswana. International Institute for Environment and Development London.

Brosius, J. P., Tsing, A. L., & Zerner, C. (1998). Representing communities: Histories and politics of community-based natural resource management. Development and Change. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00415_7.x

Carney, D. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods: What contribution can we make? Department for International Development London.

Cash, D. W., Clark, W. C., Alcock, F., Dickson, N. M., Eckley, N., Guston, D. H., Jäger, J., & Mitchell, R. B. (2003). Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(14), 8086–8091.

Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. Institute of Development Studies (UK).

Clark, V. L. P., & Creswell, J. W. (2008). The mixed methods reader. Sage.

Connell, J. P., & Kubisch, A. C. (1998). Applying a theory of change approach to the evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives: Progress, prospects, and problems. New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives, 2(15–44), 1–16.

Creswell, J. W. (2021). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research: Developments, debates, and dilemma. Berrett-Koehler Publishers Oakland.

Darghouth et al. . (2008). Watershed management approaches, policies, and operations: lessons for scaling up.

Das, P. P. (2022). Participation of rural peoples in the planning process-a case study of hailakandi development block of Southern Assam, India. Journal of Social Review and Development, 1(2), 32–36.

De Silva, M. J., Breuer, E., Lee, L., Asher, L., Chowdhary, N., Lund, C., & Patel, V. (2014). Theory of change: A theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials, 15, 1–13.

DfID, U. J. L. D. (1999). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. 445.

DfID, U. (1999a). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. London: DFID, 445, 710.

Dingman, S. L. (2015). Physical hydrology. Waveland press.

Ellis, F. (2000). Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford University Press.

Ellis, F., & Allison, E. (2004). Livelihood diversification and natural resource access. University of East Anglia.

Fabricius, C. (2013). The fundamentals of community-based natural resource management. England: In Rights Resources and Rural Development. Routledge.

FAO. (2006). The New Generation of Watershed Management Programmes and Projects: A Resource Book for Practitioners and Local Decision-makers Based on the Findings and Recommendations of an FAO Review. Food & Agriculture Org. 150

Forsyth, T. (2004). Critical political ecology: The politics of environmental science. Routledge.

France, R. L. (2006). Introduction to watershed development: Understanding and managing the impacts of sprawl. Rowman & Littlefield.

Gashaw, T. (2015). The implications of watershed management for reversing land degradation in Ethiopia. Research Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Management, 4(1), 5–12.

Gibson, C. C., & Marks, S. A. (1995). Transforming rural hunters into conservationists: An assessment of community-based wildlife management programs in Africa. World Development, 23(6), 941–957.

Gladwin, C. H., Thomson, A. M., Peterson, J. S., & Anderson, A. S. (2001). Addressing food security in Africa via multiple livelihood strategies of women farmers. Food Policy, 26(2), 177–207.

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. England: Routledge.

Gobena, T., Bantider, A., Mulugeta, M., & Teferi, E. (2024). Watershed management intervention on land use land cover change and food security improvement among smallholder farmers in Qarsa Woreda East Hararge zone Ethiopia. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Section B– Soil & Plant Science., 74(1), 2281922.

Griffith, G., Omernik, J., & Woods, A. (1999). Ecoregions, watersheds, basins, and HUCs: How state and federal agencies frame water quality. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 54(4), 666–677.

Hassan, A. A. (2008). Strategies for out-scaling participatory research approaches for sustaining agricultural research impacts. Development in Practice, 18(4–5), 564–575.

Heckman, J. J., & Vytlacil, E. (2005). Structural equations, treatment effects, and econometric policy evaluation 1. Econometrica, 73(3), 669–738.

Herrera, D., Ellis, A., Fisher, B., Golden, C. D., Johnson, K., Mulligan, M., Pfaff, A., Treuer, T., & Ricketts, T. H. (2017). Upstream watershed condition predicts rural children’s health across 35 developing countries. Nature Communications, 8(1), 811.

Hussein, K. J. L., (2002). Department for International Development. Livelihoods approaches compared.

Jabbour, C. J. C., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., Sarkis, J., & Godinho Filho, M. (2019). Unlocking the circular economy through new business models based on large-scale data: An integrative framework and research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 546–552.

Jones, B. T. (2004). CBNRM, poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods: Developing criteria for evaluating the contribution of CBNRM to poverty reduction and alleviation in southern Africa. In: Institute for Poverty Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS).

Karki, S. (2021). Sustainable livelihood framework: Monitoring and evaluation. International Journal of Social Sciences Management, 8(1), 266–271.

Kassegn, A., & Endris, E. (2021). Review on livelihood diversification and food security situations in Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agriculture & Food Security, 7(1), 1882135.

Katz, E. G. (2000). Social capital and natural capital: A comparative analysis of land tenure and natural resource management in Guatemala. Land Economics, 76(1), 114–132.

Kerr, J. (2007). Watershed management: Lessons from common property theory. International Journal of the Commons, 1(1), 89–109.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International.

Lakew, D., Carucci, V., Asrat, W., & Yitayew, A. (2005). Community based participatory watershed development: A guidelines. part 1. Ministry of Agricultural Rural Development , Addis Ababa, Ethiopia January.

Leach, M., Mearns, R., & Scoones, I. (1999). Environmental entitlements: Dynamics and institutions in community-based natural resource management. World Development, 27(2), 225–247.

Lebel, L., Anderies, J. M., Campbell, B., Folke, C., Hatfield-Dodds, S., Hughes, T. P., & Wilson, J. (2006). Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecology and society, 11 (1).

Liu, Z., Chen, Q., & Xie, H. (2018). Influence of the farmer’s livelihood assets on livelihood strategies in the western mountainous area. China. Sustainability, 10(3), 875.

Marchang, R. (2018). Land, agriculture and livelihood of scheduled tribes in North-East India. Journal of Land Rural Studies, 6(1), 67–84.

Mayne, J. (2015). Useful theory of change models. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 30(2), 119–142.

Mengistu, F., & Assefa, E. (2020). Towards sustaining watershed management practices in Ethiopia: A synthesis of local perception, community participation, adoption and livelihoods. Environmental Science & Policy, 112, 414–430.

Mfunda, I. M., & Roskaft, E. (2011). Wildlife or crop production: The dilemma of conservation and human livelihoods in Serengeti, Tanzania. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services, 7(1), 39–49.

Milupi, I., Somers, M. J., & Ferguson, J. W. H. (2017). A review of community-based natural resource management.

Mishra, A., & Das, T. K. (2017). Methods of impact evaluation: A review. Available at SSRN 2943601.

Mondal, B., Loganandhan, N., Patil, S. L., Raizada, A., Kumar, S., & Bagdi, G. L. (2020). Institutional performance and participatory paradigms: Comparing two groups of watersheds in semi-arid region of India. International Soil and Water Conservation Research, 8(2), 164–172.

Mukerjee, A. (2006). Lake watershed management in developing countries through community participation: a model. Proceedings of the 11 th World Lakes Conference-- Proceedings,

Muthle, C. (2021). Theory of Change: A Practical Guide to Social Impact. Amazon Digital Services LLC - Kdp.

Naji, T. A., Abi Teka, M., & Alemu, E. A. (2023). Level of communities’ participation in the watershed development and management practices in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Review of Socio-Economic Research and Development Studies, 7(2), 36–60.

Naji, T. A., Abi Teka, M., & Alemu, E. A. (2024). The impact of watershed on household food security: A comparative analysis. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 15, 100954.

Natarajan, N., Newsham, A., Rigg, J., & Suhardiman, D. (2022). A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Development, 155, 105898.

Ninan, K., & Lakshmikanthamma, S. (2001). Social cost-benefit analysis of a watershed development project in Karnataka, India. 157–161.

Oakley, P., Pratt, B., & Clayton, A. (1998). Outcomes and Impact: Evaluating Change in Social Development. INTRAC

Omernik, J. M., & Bailey, R. G. (1997). Distinguishing between watersheds and ecoregions 1. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 33(5), 935–949.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge university press.

Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19(3), 354–365.

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. sage.

Peet, R., & Watts, M. (2004). Liberation ecologies: Environment, development and social movements. Routledge.

Perez, C., & Tschinkel, H. (2003). Improving watershed management in developing countries: a framework for prioritising sites and practices. London, England: Overseas Development Institute. .

Rakodi, C. J. D. (1999). A capital assets framework for analysing household livelihood strategies: Implications for policy. Development Policy Review., 17(3), 315–342.

Razavi, S., Gober, P., Maier, H. R., Brouwer, R., & Wheater, H. (2020). Anthropocene flooding: Challenges for science and society. Hydrological Processes, 34(8), 1996–2000.

Reddy, V. R., & Soussan, J. (2004). Assessing the impacts of watershed development programmes: A sustainable rural livelihoods framework. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 59(3), 331.

Roba Gamo, B., Woldeamanuel Habebo, T., Tsegaye Mekonnen, G., & Park, D.-B. (2022). Determinants of community participation in a watershed development program in Southern Ethiopia. Community Development, 53(2), 150–166.

Robbins, P. (2019). Political ecology: A critical introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson education.

Saunders, S. R., & Aragón-Zavala, A. (2007). Antennas and propagation for wireless communication systems. John Wiley & Sons.

Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis.

Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171–196.

Siraw, Z., Adnew Degefu, M., & Bewket, W. (2018). The role of community-based watershed development in reducing farmers’ vulnerability to climate change and variability in the northwestern highlands of Ethiopia. Local Environment, 23(12), 1190–1206.

Solesbury, W. (2003). Sustainable livelihoods: A case study of the evolution of DFID policy. Citeseer.

Springate-Baginski, O., & Blaikie, P. (2013). Forests people and power: The political ecology of reform in South Asia. Routledge.

Srivastava, P. K., Suman, S., Pandey, V., Gupta, M., Gupta, A., Gupta, D. K., Chaudhary, S. K., & Singh, U. (2021). Concepts and methodologies for agricultural water management. In Agricultural Water Management: Elsevier.

Sutherland, A., Irungu, J., Kang’ara, J., Muthamia, J., & Ouma, J. (1999). Household food security in semi-arid Africa—the contribution of participatory adaptive research and development to rural livelihoods in Eastern Kenya. Food Policy, 24(4), 363–390.

UN. (2008). Achieving Sustainable Development and Promoting Development Cooperation: Dialogues at the Economic and Social Council. United Nations. Office for ECOSOC Support Coordination. https://books.google.com.et/books?id=ROhrzQEACAAJ

Usman, M. O. (2018). Holocene climate-and anthropogenically-driven mobilization of terrestrial organic matter ETH Zurich].

Valters, C. (2014). Theories of change in international development: Communication, learning, or accountability.

Vogel, C., Susanne, C. M., Roger, E. K., & Geoffrey, D. D. (2012). Linking vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience science to practice: pathways, players and partnerships1. England: In Integrating science and policy Routledge.

Vörösmarty, C., Fekete, B. M., Meybeck, M., & Lammers, R. B. (2000). Global system of rivers: Its role in organizing continental land mass and defining land-to-ocean linkages. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 14(2), 599–621.

Wang, G., Mang, S., Cai, H., Liu, S., Zhang, Z., Wang, L., & Innes, J. L. (2016). Integrated watershed management: Evolution, development and emerging trends. Journal of Forestry Research, 27, 967–994.

Wang, L. K., & Yang, C. T. (2014). Modern Water Resources Engineering. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Wani, S. P., & Garg, K. K. (2009). Watershed management concept and principles.

Wani, S. P., Venkateswarlu, B., & Sharda, V. (2011). Watershed development for rainfed areas: Concept, principles, and approaches.

Wani, S., Sreedevi, T., Reddy, T. V., Venkateshvarlu, B., & Prasad, C. S. (2008). Community watersheds for improved livelihoods through consortium approach in drought prone rainfed areas. Journal of Hydrological Research and Development, 23, 55–77.

Wasonga, V., Kambewa, D., & Bekalo, I. (2010). Community-based natural resource management. Managing Natural Resources for Development in Africa: A Resource Book, 165.

Weiss, C. H. (1997). Theory-based evaluation: Past, present, and future. New Directions for Evaluation, 76, 41–55.

Woodhouse, P., & Muller, M. (2017). Water governance—An historical perspective on current debates. World Development, 92, 225–241.

Zhang, C., & Tang, H. (2010). Advances in Water Resources & Hydraulic Engineering: Proceedings of 16th IAHR-APD Congress and 3rd Symposium of IAHR-ISHS. Springer Berlin Heidelberg

Funding

The authors declare that there was no funding to conduct this study, it is a part of a PhD dissertation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Temesgen Argaw Naji: conceptualisation, investigation, data collection, formal analysis, methodology, software, and writing—original draft. Meskerem Abi Teka: resources, supervision, writing—review and editing, and validation. Esubalew Abate Alemu: resources, supervision, writing—review and editing, and validation. All authors reviewed and submitted the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this study.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Addis Ababa University, College of Developmental Studies. In addition, the participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naji, T.A., Teka, M.A. & Alemu, E.A. Designing a framework to analyze the impact of watershed development on socioeconomic development: integrating literature, theory, and practice. GeoJournal 89, 223 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11223-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11223-2