Abstract

By considering situations from the paradox of the twins in relativity, it is shown that time passes at different rates along different world lines, answering some well-known objections. The best explanation for the different rates is that time indeed passes. If time along a world line is something with a rate, and a variable rate, then it is difficult to see it as merely a unique, invariant, monotonic parameter without any further explanation of what it is. Although it could, conceivably, be explained by the flow of something, it is better explained by the passing of a point present, which faces the problem that there is no absolute simultaneity in special relativity so that the present for an object is confined to just that object. This raises problems about presentism, eternalism, simultaneity, and special relativity. These issues are addressed first by giving accounts of presentism and eternalism and then an account of existence and times for objects relative to world lines. Finally, an analogy between a world of relativistic objects and Leibniz’s ontology of monads.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“The four-dimensional continuum is now no longer resolvable objectively into sections, which contain all simultaneous events; “now” loses for the spatially extended world its objective meaning. It is because of this that space and time must be regarded as a four-dimensional continuum that is objectively unresolvable” [9, p. 371]. “From now onwards space by itself and time by itself will recede completely to become mere shadows and only a type of union of the two will still stand independently on its own” [32, p. 39]. Similar views have been expressed recently by people such as Barbour [3] and Saunders [39].

For a recent discussion of the paradox of the twins, see Maudlin [26, pp. 77–83].

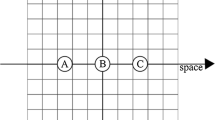

Spatially, all these situations could look the same. For A, the time taken between meetings with B are the same and from the point of view of A’s rest frame, the spatial distance covered by B could be the same in all these situations.

Seungil Lee has drawn similar conclusions by just considering the time dilation formula. I am very grateful to him for a number of helpful discussions.

That it is imaginary is physically significant, just because time cannot pass between two such points. Nevertheless, some people switch signs and talk about proper distance, which is a matter of switching the signature of the metric: proper time is (dτ)2 = (cdt)2 – (dx)2 and proper distance would be (ds)2 = (dx)2 – (cdt)2. Maudlin [26, p. 71], like some others, appears to believe that it is not physically significant.

It is interesting that Riggs [37] thinks that a spatial analogue of the passage of time can be found in the expansion of the universe.

A point emphasized by Maudlin [24].

The following is a summary of some of the things that Maudlin [24, p. 263] has said about the objection that a rate of passing of time of one second per second makes no sense. Consider π and the square root of two. π can be approximated to by 3.1415 feet per foot, or metres per metre and the square root of two by 1.414 feet per foot, or metres per metre. It has to be understood that both of them are ratios of lengths. Both make sense within a certain context. Although not exactly analogous to the rate of passing of time, they do show that it is conceivable that a significant rate could involve the same unit.

Markosian [22] discusses issues that mainly concern philosophers, such as singular propositions and referring to non-present objects, relations between present and non-present objects (transtemporal relations), and referring to past and future times. My view is that relativity implies that there are causal relations that are transtemporal, and that that makes reference to past objects non-problematic. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on presentism [16] has a similar agenda but adds a discussion of truth makers reflecting current interests. See also Zimmerman [50, pp. 206–219], Lowe [21] and other contributors to that volume. Dieks [8] defends the view that along two different world lines there is a linear temporal ordering and a local temporal becoming, cf. [7]. Hinchcliff [15] discusses a number of versions of relativized presentism, including Point Presentism and Cone Presentism.

The views of Miller and Leininger are very similar. In Miller’s account of eternalism, the growing block, and the moving spotlight views, her definitions are about events as well as times [31, pp. 347–8]. Her later discussions of presentism appear to take it to be mainly about events.

Most of these do not concern us, though the point presentism of Harrington [14] is of some interest.

Standard synchrony is assumed here. Some people believe that it is a convention; others maintain that it is not, see [47, pp. 1338–9] for a brief account.

According to Rovelli [38], II, p. 1 “Presentism is the idea that there is now a unique real objective three-dimensional present extending all over the universe, formed by the ensemble of the events that are ‘real now’. As time passes, events in the present become past, while future events become present: this is becoming.” According to Thyssen [47, p. 1340]: “we will take the present to be a three-dimensional Cauchy hyperplane, spanning the entire spatial extent of the world. Call this the hyperplane present.” “On the presentist view, the present is singled out as a uniquely special moment we call now. Only those events that constitute the present moment are real. Past events are no longer real and future events are not yet real.” Hinchcliff [15] discusses a number of versions of relativized presentism, including point presentism and cone presentism.

Basic presentism is a metaphysical position. Generally speaking, if a metaphysical position is true, then it is necessarily true. Hence, basic presentism can be spelled out as: in all possible worlds in which there is time, there is a present or many presents. It follows that a present is essential to time, though this is also true for the moving spotlight view. It could then perhaps be objected that in our world although there is something conventionally called space-time, there is no time and hence no present. But unless it is purely a mathematical exercise, it will include an attempt to account for the well-known phenomenon that we experience and measure. For basic presentism, a present is essential to time; for basic eternalism, it is not.

Of course, presentists might complain that it cannot be a temporal continuum if there is no present, though by hypothesis it is a continuum of some sort.

The Russell–Frege view is that when ‘exists’ is predicated of a certain object, it should be understood in terms of some other sentence involving the existential quantifier that gives the correct logical form. McGinn [29] believes that existence is a primitive, unanalysable property of some objects, but makes a distinction between existence and being. Another option, which I prefer, is that ‘exists’ is a primitive, unanalysable predicate whose use is well known, even though it does not refer to a property. It is also univocal in that there is only one kind of existence, and it is a transcendental in that it applies to all entities in all categories. Grossmann [13], Chap. IV has an interesting discussion of existence in which he defends the univocity of existence. In contrast, McDaniel [28] believes that there are many kinds of existence. Someone who used ‘real’ as a technical term would have to state or presuppose reality conditions. For example, Frege [11] thought that real things had some causal significance and that there existed things that were not real. For Lange [17], relativistic invariance is the mark of the real, though, presumably, he thinks other things exist.

Tallant [45] among others does not retain this distinction.

The growing block universe theory maintains such a view for the whole of space-time, and as such is inconsistent with special relativity.

Counting of repetitions in the present is conceptually different from measuring something analogous to a length along a pre-existing line, which is how eternalism must see the measurement of time, cf. [24].

From this point of view, the moving spotlight view is incoherent since it recognizes two sorts of temporal continua. Since there is a present, there is also a temporal continuum that is a construction. And there is also a temporal continuum that actually exists and pre-exists any repetitions of any phenomenon. It is difficult to see the relevance of the second, pre-existing temporal continuum to the passing of time. Leininger [19, pp. 728–9] maintains that the moving spotlight view encounters problems arising from McTaggart’s paradox whereas presentism proper does not. The moving spotlight theory has been defended by Skow [40] and more recently by Skow [41] and Cameron [6].

One of the problems with perdurantism is that for an accelerated extended object, the world tube will curve and so the time slices will intersect with each other within the world tube. Balashov [2] mentions a similar problem for scattered objects. Parsons [34] has suggested that four-dimensional objects do not have temporal parts, which has been rejected by Miller [30].

For the notion of existence conditions, see [20, p. 1]: “According to this conception of the aim and content of metaphysical theory, metaphysics is above all concerned with identifying, as perspicuously as it can, the fundamental ontological categories to which all entities, actual and possible, belong. This it does by articulating the existence and identity conditions distinctive of the members of each category and the relations of ontological dependency in which the members of any given category characteristically stand to other entities, either of the same or of different categories.” That the world line of an object should be continuous is part of the identity conditions for objects, see for example [48, p. 37] and [49, p. 70].

“Two people pass each other on the street; and according to one of the two people, an Andromedean space fleet has already set off on its journey, while to the other, the decision as to whether or not the journey will actually take place has not yet been made. How can there still be some uncertainty as to the outcome of that decision? If to either person the decision has already been made, then surely there cannot be any uncertainty. The launching of the space fleet is an inevitability.”

See fn. 14. The world line of the second observer does not have to be straight, since the only point that matters on the second observers world line is the point of reflection.

Cf. Synge [44, p. 108] “For us time is the only basic measure. Length (or distance [or quasi-distance, or indeed any assertion of “spatial extension”]), in so far as it is necessary or desirable to introduce it, is strictly a derived concept.”

Of course, there are people who have attempted such justifications, such as the defenders of substantivalism.

See [18]. There is some causality in his universe since God creates and annihilates monads.

There is no problem in claiming that for a collection of island universes each of them exists.

References

Armstrong, D.M.: Nominalism and Realism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1978)

Balashov, Y.: Do composite objects have an age in relativistic spacetime? Philosophia Naturalis 49, 9–23 (2012)

Barbour, J.: The End of Time. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

Bondi, H.: Relativity and Common Sense. Doubleday, New York (1964)

Brown, H.: Physical Relativity. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

Cameron, R.P.: The Moving Spotlight: An Essay on Time and Ontology. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

Dieks, D.: Special relativity and the flow of time. Philosophy of Science 55, 456–460 (1988)

Dieks, D.: Becoming, relativity and locality. In: Dieks, D. (ed.) The Ontology of Spacetime (vol. 1). Elsevier, Amsterdam (2006)

Einstein, A.: Ideas and Opinions. Crown Publishers, New York (1954)

Francis, C.: Conceptual Foundations of Special and General Relativity. arXiv:physics/9909048 (1999)

Frege, G.: Foundations of Arithmetic. J.L. Austin (trans.). Blackwell 1968 original (1884)

Frege, G.: Thoughts in Collected Papers on Mathematics, Logic, and Philosophy. In: B. McGuinness (ed.). Oxford: Blackwell, 1984 original (1918)

Grossmann, R.: The Existence of the World. Routledge, London (1992)

Harrington, J.: Special relativity and the future: a defense of the point present. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. B 39, 82–101 (2008)

Hinchcliff, M.: A defense of presentism in a relativistic setting. Philos Sci. 67(Supplement), S575–S586 (2000)

Ingraham, D. & Tallant, J.: Presentism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2018)

Lange, M.: Introduction to Philosophy of Physics. Blackwell, Oxford (2002)

Leibniz, G.: The Monadology in Leibniz The Monadology and Other Philosophical Writings, R. Latta (trans.) Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1898 original (1714)

Leininger, L.: Presentism and the myth of passage. Austral. J. Philos 93(4), 724–739 (2015)

Lowe, E.J.: Metaphysics as the Science of Essence, unpublished (2007)

Lowe, E.J.: Presentism and Relativity: No Conflict in New Papers on the Present. Philosophia Verlag, Munich (2013)

Markosian, N.: A Defense of Presentism. In: Zimmerman, D.W. (ed.) Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, vol. 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2004)

Markossian, N.: How fast does time pass? Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 53, 829–844 (1993)

Maudlin, T.: Remarks on the passing of time. Proc. Aristotelian Soc. New Ser. 102, 259–274 (2002)

Maudlin, T.: The Metaphysics within Physics. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2007)

Maudlin, T.: The Philosophy of Physics: Space and Time. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2012)

Maudlin, T.: A rate of passage. Manuscrito Rev. Int. Fil. Campinas 40, 75–79 (2017)

McDaniel, K.: The Fragmentation of Being. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2017)

McGinn, C.: Logical Properties. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2000)

Miller, K.: Ought a four-dimensionalist to believe in temporal parts? Canad. J. Philos. 39, 619–646 (2009)

Miller, K.: Presentism, eternalism, and the growing block. In: Dyke, H., Bardon, A. (eds.) A Companion to the Philosophy of Time. Blackwell, Oxford (2013)

Minkowski, H.: Space and time, lecture of 1908. In: Petkov, V. (ed.) Space and Time: Minkowski’s Papers on Relativity. Minkowski Institute Press, Montreal (2012)

Müller, T.: Defining a relativity-proof notion of the present via spatio-temporal indeterminism. Found. Phys. 50, 644–664 (2020)

Parsons, J.: Must a four dimensionalist believe in temporal parts? Monist 83, 399–418 (2000)

Penrose, R.: The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and Laws of Physics. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1989)

Price, H.: Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’s Point. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1996)

Riggs, P.J.: Is there a spatial analogue of the passage of time? Filosofiâ I Kosmologiâ 18(1), 12–21 (2017)

Rovelli, C.: Neither presentism nor eternalism. Found. Phys. 49(12), 1325–1335 (2019)

Saunders, S.: How relativity contradicts presentism. R. Inst. Philos. Suppl. 50, 277–292 (2002)

Skow, B.: Relativity and the moving spotlight. J. Philos. 106(12), 666–678 (2009)

Skow, B.: Objective Becoming. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

Sider, T.: Quantifiers and temporal ontology. Mind 115(457), 75–97 (2006)

Slavov, M.: Eternalism and perspectivalist realism about the ‘Now.’ Found. Phys. 50, 1398–1410 (2020)

Synge, J.L.: Relativity: The General Theory. North Holland, Amsterdam (1960)

Tallant, J.: Temporal passage and the ‘no alternate possibilities argument.’ Manuscrito Rev. Int. Fil. Campinas 39, 36–47 (2017)

Tallant, J.: Defining existence presentism. Erkenntnis 79, 479–501 (2014)

Thyssen, P.: Conventionality and reality. Found. Phys. 49(12), 1336–1354 (2019)

Wiggins, D.: Identity and Spatio-temporal Continuity. Blackwell, Oxford (1967)

Wiggins, D.: Sameness and Substance Renewed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2001)

Zimmerman, D.: Temporary intrinsics and presentism. In: van Inwagen, P., Zimmerman, D.W. (eds.) Metaphysics: The Big Questions. Blackwell, Oxford (1998)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Newman, A. The Rates of the Passing of Time, Presentism, and the Issue of Co-Existence in Special Relativity. Found Phys 51, 68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10701-021-00469-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10701-021-00469-2