Abstract

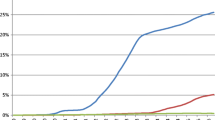

Is there discrimination in mortgage-loan origination and pricing? If so, does the level of discrimination differ before and after the eruption of the subprime crisis? Using data from 6.5 million loan applications from 2004 through 2013, we propose a novel approach aiming to substantially lower the notorious omitted-variable bias of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) database and identify the level of racial, ethnic, and gender discrimination in mortgage lending across the United States. In stark contrast with previous studies, we find, on average, very little discrimination in loan origination. Although discrimination increases somewhat after 2007, its probability remains well below 1%. In contrast, we find that white (non-Hispanic) applicants pay a lower spread on the originated loans by 0.37 (0.11) basis points, a result that almost entirely comes from the pre-crisis period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Between 2007 and 2009 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed numerous class action lawsuits against a number of the United States’ largest lenders for discriminatory lending practices (Sen 2012) including, among others, Wells Fargo & Co, HSBC Finance Corporation, CitiMortgage, SunTrust Mortgage, JP Morgan, First Horizon, Ameriquest Mortgage Company, Fremont Investment & Loan, Option One Mortgage Corporation, WMC Mortgage Corporation, Long Beach Mortgage Company, BNC Mortgage, Accredited Home Lenders, Bear Stearns Residential Mortgage Corporation, Encore Credit, First Franklin Financial Corporation and Washington Mutual, Inc. The class action lawsuits alleged that the financial institutions violated the Fair Housing Act, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 engaging in systematic, institutionalized racism and discriminatory practices in home mortgage lending. A more detailed analysis on the aforementioned lawsuit cases is available at: http://www.naacp.org.

The Fair Housing Act was enacted in 1968 by the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to prohibit discrimination based on race (Hubbard et al. 2012).

The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) and the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) were enacted by Congress in 1975 and 1977, respectively, to monitor lending institutions’ practices toward minorities and low-income borrowers and neighborhoods (Hubbard et al. 2012).

Empirically distinguishing between these forces is very hard because of a lack of specialized data.

Ladd (1998), LaCour-Little (1999), Turner and Skidmore (1999), Ross and Yinger (2002, 2006), and Ross (2005) provide an exhaustive review of the earlier literature on mortgage lending discrimination. For more recent studies, see Pager and Shepherd (2008), Hubbard et al. (2012), Sen (2012), and Wheeler and Olson (2015) and references therein.

According to the Pew Research Centre (2011), from 2008 to 2010, unemployment increased among the white population by 4.7% (from 4.9% to 9.6%), among the African-American population by 7.9% (from 9.4% to 17.3%), and among the Asian population by 5.2% (from 3.2% to 8.4%). Further, African-American and Hispanic households lost 53% and 66% of their wealth, respectively, between 2005 and 2009. During the same period, white households’ wealth dropped by 16%. Also, Hoynes et al. (2012) provide evidence that the effect of the 2007–2009 recession in the labor market differs across demographic groups, with African-American and Hispanic workers being more affected. Experience from earlier crises suggests that these differences are stable through all the recessionary periods for the last three decades.

The census tract is an area roughly equivalent to a neighborhood established by the Bureau of Census for analyzing populations. Census tracts generally encompass a population between 2500 to 8000 people, and represent the smallest territorial unit for which population data are available.

There are a number of issues we examine to ensure that estimation with the linear probability model is not problematic. The two main problems of the LPM vis-à-vis the probit or logit models are heteroscedasticity and the out-of-bound (out of the 0 and 1 bounds) predictions (Wooldridge 2009). Heteroscedasticity is easily resolved with the estimation with robust standard errors. The out-of-bound problem is not that large in our sample, where for e.g. the baseline regression with the full sample, 3045 observations out of the 6,452,279 are below 0 and 127 are above 1. This is less than 0.05% of our sample. Thus, we anticipate very little econometric problems with the OLS estimation. Our best bet to actually show that this is indeed the case, would be to show that results from probit or logit models without fixed effects are similar to results from the LPM and no fixed effects. Unfortunately, even the simple logit or probit models do not converge in our data set.

In fact, econometrically it is not even possible to include \( {u}_i^D \) in Eq. (6) because \( {L}_i^D={L}_i^S \) and, if included, \( {u}_i^h \) drops out from the regression due to perfect collinearity.

The estimates become even more economically significant if we remove the regional fixed effects, and they decrease by about 10% if we include bank fixed effects.

To further compare our findings with the existing literature, and especially the seminal study of Munnell et al. (1996), we collect HMDA data for Boston (Suffolk County) in 1990. As in Munnell et al., we identify 1200 black and Hispanic applicants and choose a random sample of white applicants to produce roughly equal numbers of white and minority denials (10% rejection rate and 3300 applications by whites). Using that sample, we run a basic model, which includes race, income, gender, and census tract fixed effects as explanatory variables. We find a discrimination estimate of 11.4%. Recall that Munnell et al. find an estimate of 8% when adding 38 more variables, which are not available to us (data are confidential). Then, we repeat the analysis using our method and find an estimate of 0.9%. We report these results in Table 13 of the Appendix. Thus, we must conclude that there is still a lot of omitted-variable bias in the study by Munnell et al. (1996).

As we showed earlier, including or excluding income in the first stage of the model does not significantly affect our results. From this point onward, we retain the specification with income included in the first stage of the model.

Available online in http://mcdc2.missouri.edu/websas/geocorr2k.html.

For the mean applicant, the spread is 5.07 basis points, implying that white applicants pay approximately a 7.3% lower spread.

References

Avery RB, Canner GB, Cook RE (2005) New information reported under HMDA and its application in fair lending enforcement. Fed Reserv Bull 91:344–394

Avery RB, Bhutta N, Brevoort KP, Canner GB, Gibbs CN (2010) The 2008 HMDA data: the mortgage market during a turbulent year. Fed Reserv Bull 96:169–211

Bayer P, Ferreira F, Ross SL (2014). Race, ethnicity and high-cost mortgage lending. NBER working paper No. 20762

Bocian DG, Ernst KS, Li W (2008) Race, ethnicity and subprime home loan pricing. J Econ Bus 60:110–124

Cheng P, Lin Z, Liu Y (2011) Do women pay more for mortgages? J Real Estate Financ Econ 43:423–440

Cheng P, Lin Z, Liu Y (2014) Racial discrepancy in mortgage interest rates. J Real Estate Financ Econ 51:101–120

Courchane MJ (2007) The pricing of home mortgage loans to minority borrowers: how much of the APR differential can we explain? Journal of Real Estate Research 29:399–440

Day TE, Liebowitz SJ (1998) Mortgage lending to minorities: Where’s the bias? Econ Inq 36:3–28

DeLoughy ST (2012) Risk versus demographics in subprime mortgage lending: evidence from three Connecticut cities. J Real Estate Financ Econ 45:569–587

Erickson T, Jiang CH, Whited TM (2014) Minimum distance estimation of the errors-in-variables model using linear cumulant equations. J Econ 183:211–221

European Union, Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2010) Protecting fundamental rights during the economic crisis, working paper (December). Available at: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/1423-FRA-Working-paper-FR-during-crisis-Dec10_EN.pdf

Faber JW (2013) Racial dynamics of subprime mortgage lending at the peak. Housing Policy Debate 23:328–349

Ferguson M, Peters S (1995) What constitutes evidence of discrimination in mortgage lending? J Financ 50:739–748

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (2006) Mortgage loan fraud: An industry assessment based upon suspicious activity report analysis. Available at: http://www.fincen.gov/news_room/rp/reports/pdf/MortgageLoanFraud.pdf

Ghent AC, Hernández-Murillo R, Owyang MT (2014) Differences in subprime loan pricing across races and neighborhoods. Reg Sci Urban Econ 48:199–215

Harrison GW (1998) Mortgage lending in Boston: a reconsideration of the evidence. Econ Inq 36:29–38

Haughwout A, Mayer C, Tracy J, Jaffee DM, Piskorski T (2009) Subprime mortgage pricing: the impact of race, ethnicity, and gender on the cost of borrowing. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs, 33–63

Holmes A, Horvitz P (1994) Mortgage redlining: Race, risk, and demand. J Financ 49:81–99

Horne DK (1997) Mortgage lending, race and model specification. J Financ Serv Res 11:43–68

Hoynes H, Miller DL, Schaller J (2012) Who suffers during recessions? J Econ Perspect 26:27–47

Hubbard RG, Palia D, Yu W (2012) Analysis of discrimination in prime and subprime mortgage markets. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1975789

International Labour Office (2011) Equality at work: the continuing challenge. Global report under the follow-up to the ILO declaration on fundamental principles and rights at work. International labour conference, 100th session, Geneva

LaCour-Little M (1999) Discrimination in mortgage lending: a critical review of the literature. J Real Estate Lit 7:15–50

Ladd H (1998) Evidence of discrimination in mortgage lending. J Econ Perspect 12:41–62

Mian AR, Sufi A (2015) Fraudulent Income Overstatement on Mortgage Applications during the Credit Expansion of 2002 to 2005. NBER Working Paper No. 20947

Munnell AH, Tootell GM, Browne LE, McEneaey J (1996) Mortgage lending in Boston: Interpreting HMDA data. Am Econ Rev 86:25–53

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (2007) The NAACP filed a historic lawsuit against mortgage lenders alleging racial discrimination. Available at: http://www.naacp.org

Ondrich J, Ross S, Yinger J (2003) Now you see it, now you don’t: why do real estate agents withhold available houses from black customers? Rev Econ Stat 85:854–873

Pager D, Shepherd H (2008) The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol 34:181–209

Pew Research Centre (2011) Wealth gaps rise to record highs between Whites, Blacks and Hispanics. Social and Demographic Trends. Available at: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2011/07/SDT-Wealth-Report_7-26-11_FINAL.pdf

Piskorski T, Seru A, Witkin J (2015) Asset quality misrepresentation by financial intermediaries: evidence from the RMBS market. J Financ 70:2635–2678

Quillian L (2006) New approaches to understanding racial prejudice and discrimination. Annu Rev Sociol 32:299–328

Reskin B (2012) The race discrimination system. Annu Rev Sociol 38:17–35

Ross SL (2005) The continuing practice and impact of discrimination. University of Connecticut. Department of Economics Working Paper Series 19

Ross SL, Yinger J (2002) The color of credit: mortgage lending discrimination, research methodology and fair lending enforcement. MIT Press, Cambridge

Ross SL, Yinger J (2006) Uncovering discrimination: a comparison of the methods used by scholars and civil rights enforcement officials. American Law and Economics Review 8:562–614

Rugh JS, Massey DS (2010) Racial segregation and the American foreclosure crisis. Am Sociol Rev 75:629–651

Sen M (2012) Quantifying discrimination: Exploring the role of race and gender and the awarding of subprime mortgage loans. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1593183

Turner MA, Skidmore F (1999) Mortgage lending discrimination: a review of existing evidence. Urban Institute Press, Washington, DC

United Nations Educational, Scientific and cultural organization (UNESCO) (2009). The impact of the economic crisis on discrimination and xenophobia. Global Migration Group (GMG). Available at: www.globalmigrationgroup.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/UNESCO_Fact-sheet_final.pdf

Wheeler CH, Olson LM (2015) Racial differences in mortgage denials over the housing cycle: Evidence from US metropolitan areas. J Hous Econ 30:33–49

Williams R, Nesiba R, McConnell ED (2005) The changing face of inequality in home mortgage lending. Soc Probl 52:181–208

Wooldridge JM (2009) Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason

Yinger J (1986) Measuring racial discrimination with fair housing audits: caught in the act. Am Econ Rev 76:881–893

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The tables in this appendix are for online use only. They include the following information:

Table 12 reports the results from the estimation of Eq. (5) without the previous estimation of Eqs. (2)–(4) and the inclusion of the component e among the regressors in Eq. (5).

Table 13 reports the results from an analysis similar to Munnell et al. (1996). See also footnote 12 of the main text.

Table 14 reports the results from the analysis on income misreporting, which includes only zip codes with mortgage-loan misrepresentation values at the lowest 5% centile of the distribution of the misrepresentation measure compiled by Piskorski et al. (2015).

Table 15 reports the results after orthoganilizing the three discrimination dummy variables and \( {u}_i^D \) and \( {u}_i^S \).

Table 16 compares the results from the logit model without fixed effects (marginal effects) with the equivalent OLS results (again without fixed effects).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Delis, M.D., Papadopoulos, P. Mortgage Lending Discrimination Across the U.S.: New Methodology and New Evidence. J Financ Serv Res 56, 341–368 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-018-0290-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-018-0290-0