Abstract

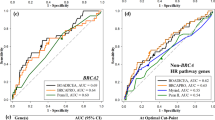

We have designed the user-friendly COS software with the intent to improve estimation of the probability of a family carrying a deleterious BRCA gene mutation. The COS software is similar to the widely-used Bayesian-based BRCAPRO software, but it incorporates improved assumptions on cancer incidence in women with and without a deleterious mutation, takes into account relatives up to the fourth degree and allows researchers to consider an hypothetical third gene or a polygenic model of inheritance. Since breast cancer incidence and penetrance increase over generations, we estimated birth-cohort-specific incidence and penetrance curves. We estimated breast and ovarian cancer penetrance in 384 BRCA1 and 229 BRCA2 mutated families. We tested the COS performance in 436 Italian breast/ovarian cancer families including 79 with BRCA1 and 27 with BRCA2 mutations. The area under receiver operator curve (AUROC) was 84.4 %. The best probability threshold for offering the test was 22.9 %, with sensitivity 80.2 % and specificity 80.3 %. Notwithstanding very different assumptions, COS results were similar to BRCAPRO v6.0.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Breast Cancer Linkage (1999) Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1310–1316

Brose MS, Rebbeck TR, Calzone KA, Stopfer JE, Nathanson KL, Weber BL (2002) Cancer risk estimates for BRCA1 mutation carriers identified in a risk evaluation program. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:1365–1372

Easton DF, Bishop DT, Ford D, Crockford GP (1993) Genetic linkage analysis in familial breast and ovarian cancer: results from 214 families. The breast cancer linkage consortium. Am J Hum Genet 52:678–701

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M et al (1998) Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The breast cancer linkage consortium. Am J Hum Genet 62:676–689

Narod S, Ford D, Devilee P et al (1995) Genetic heterogeneity of breast-ovarian cancer revisited. Breast cancer linkage consortium. Am J Hum Genet 57:957–958

Bonadona V, Sinilnikova OM, Chopin S et al (2005) Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutations to the incidence of breast cancer in young women: results from a prospective population-based study in France. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 43:404–413

Hopper JL, Southey MC, Dite GS et al (1999) Population-based estimate of the average age-specific cumulative risk of breast cancer for a defined set of protein-truncating mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Australian breast cancer family study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8:741–747

Loman N, Bladstrom A, Johannsson O, Borg A, Olsson H (2003) Cancer incidence in relatives of a population-based set of cases of early-onset breast cancer with a known BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status. Breast Cancer Res 5:R175–R186

Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S et al (1997) The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med 336:1401–1408

Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE et al (2006) Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1694–1706

Thorlacius S, Struewing JP, Hartge P et al (1998) Population-based study of risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA2 mutation. Lancet 352:1337–1339

Anglian Breast Cancer Study Group (2000) Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based series of breast cancer cases. Br J Cancer 83:1301–1308

Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D et al (2013) Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:812–822

Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S et al (2003) Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 72:1117–1130

Chen S, Parmigiani G (2007) Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol 25:1329–1333

Antoniou AC, Easton DF (2006) Models of genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Oncogene 25:5898–5905

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD (1994) Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer 73:643–651

Federico M, Maiorana A, Mangone L et al (1999) Identification of families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer for clinical and mammographic surveillance: the Modena Study Group proposal. Breast Cancer Res Treat 55:213–221

Frank TS, Deffenbaugh AM, Reid JE et al (2002) Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J Clin Oncol 20:1480–1490

Shattuck-Eidens D, Oliphant A, McClure M et al (1997) BRCA1 sequence analysis in women at high risk for susceptibility mutations. Risk factor analysis and implications for genetic testing. JAMA 278:1242–1250

Berry DA, Parmigiani G, Sanchez J, Schildkraut J, Winer E (1997) Probability of carrying a mutation of breast-ovarian cancer gene BRCA1 based on family history. J Natl Cancer Inst 89:227–238

Parmigiani G, Berry D, Aguilar O (1998) Determining carrier probabilities for breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet 62:145–158

Andersen TI (1996) Genetic heterogeneity in breast cancer susceptibility. Acta Oncol 35:407–410

Berrino F, Pasanisi P, Berrino J, Curtosi P, Bellati C (2002) A European case-only study on familial breast cancer. IARC Sci Publ 156:63–65

Pasanisi P, Berrino J, Fusconi E, Curtosi P, Berrino F (2005) A European case-only study (COS) on familial breast cancer. J Nutr 135:3040S–3041S

Pasanisi P, Hédelin G, Berrino J et al (2009) Oral contraceptive use and BRCA penetrance: a case-only study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:2107–2113

Pasanisi P, Bruno E, Manoukian S, Berrino F (2013) A randomized controlled trial of diet and physical activity in BRCA mutation carriers. Fam Cancer. doi:10.1007/s10689-013-9691

Parkin D, Whelan SL, Ferlay J (2002) Cancer incidence in five continents. IARC scientific publication no. 155. IARC Press, Lyon

Capocaccia R, Verdecchia A, Micheli A, Sant M, Gatta G, Berrino F (1990) Breast cancer incidence and prevalence estimated from survival and mortality. Cancer Causes Control 1:23–29

Chang-Claude J, Becher H, Eby N, Bastert G, Wahrendorf J, Hamann U (1997) Modifying effect of reproductive risk factors on the age at onset of breast cancer for German BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 123:272–279

Narod SA, Goldgar D, Cannon-Albright L et al (1995) Risk modifiers in carriers of BRCA1 mutations. Int J Cancer 64:394–398

Tryggvadottir L, Sigvaldason H, Olafsdottir GH et al (2006) Population-based study of changing breast cancer risk in Icelandic BRCA2 mutation carriers, 1920–2000. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:116–122

Antoniou AC, Pharoah PP, Smith P, Easton DF (2004) The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 91:1580–1590

Lee AJ, Cunningham AP, Kuchenbaecker KB, Mavaddat N, Easton DF, Antoniou AC (2014) BOADICEA breast cancer risk prediction model: updates to cancer incidences, tumour pathology and web interface. Br J Cancer 110:535–545

Roudgari H, Miedzybrodzka ZH, Haites NE (2008) Probability estimation models for prediction of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: COS compares favourably with other models. Fam Cancer 7:199–212

Manoukian S, Peissel B, Pensotti V et al (2007) Germline mutations of TP53 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer/sarcoma families. Eur J Cancer 43:601–606

Radice P (2002) Mutations of BRCA genes in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 21:9–12

Lindor NM, Guidugli L, Wang X et al (2012) A review of a multifactorial probability-based model for classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Hum Mutat 33:8–21

Verdecchia A, Capocaccia R, Egidi V, Golini A (1989) A method for the estimation of chronic disease morbidity and trends from mortality data. Stat Med 8:201–216

Berrino F, Capocaccia R, Esteve J et al (1999) Survival of cancer patients in Europe: the EUROCARE-2 study. IARC scientific publications no. 151, Lyon

Berrino F, Capocaccia R, Coleman P et al (2003) Survival of cancer patients in Europe: the EUROCARE-3 study. Ann Oncol 14:v1–v155

De Angelis G, De Angelis R, Frova L, Verdecchia A (1994) MIAMOD: a computer package to estimate chronic disease morbidity using mortality and survival data. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 44:99–107

Micheli A, Verdecchia A, Capocaccia R et al (1992) Estimated incidence and prevalence of female breast cancer in Italian regions. Tumori 78:13–21

Gonzalez-Diego P, Lopez-Abente G, Pollan M, Ruiz M (2000) Time trends in ovarian cancer mortality in Europe (1955–1993): effect of age, birth cohort and period of death. Eur J Cancer 36:1816–1824

Press WH, Tekolski SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP (1992) Numerical Recipes in C: the art of scientific computing, 2edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Chen S, Iversen ES, Friebel T et al (2006) Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a large United States sample. J Clin Oncol 24:863–871

Begg CB, Haile RW, Borg A et al (2008) Variation of breast cancer risk among BRCA1/2 carriers. JAMA 299:194–201

Eccles SA, Aboagye EO, Ali S et al (2013) Critical research gaps and translational priorities for the successful prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 15:R92

Ford D, Easton DF, Peto J (1995) Estimates of the gene frequency of BRCA1 and its contribution to breast and ovarian cancer incidence. Am J Hum Genet 57:1457–1462

National Cancer Institute. (2013) Genetics of breast and ovarian cancer (PDQ). http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/breast-and-ovarian/HealthProfessional/page2

Malone KE, Daling JR, Doody DR et al (2006) Prevalence and predictors of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based study of breast cancer in white and black American women ages 35–64 years. Cancer Res 66:8297–8308

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD (1991) Genetic analysis of breast cancer in the cancer and steroid hormone study. Am J Hum Genet 48:232–242

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL (1988) Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44:837–845

Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF (2006) The inconsistency of “optimal” cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Epidemiol 163:670–675

Acknowledgments

The study was financed by the 6th Framework Program of the European Community and by funds from Italian citizens who allocated the 5 × 1,000 share of their tax payment in support of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, according to Italian laws (INT-Institutional strategic projects ‘5 × 1,000’). We also thank Dr Maria Teresa Penci for help with the language and Dr Giulietta Scuvera for data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

We have modified the original method of Parmigiani et al. [22] in three different points. First, we have included third degree relatives plus the grandparent sibling offspring (IV degree); second, we use age and birth cohort specific incidence and penetrance; third, we have incorporated the possibility of taking into account an hypothetical third gene. We present here the formulas respecting as far as possible the notation that Parmigiani used in his article.

For each family member b, the contribution to the likelihood function depends on the age a b , the genetic status of BRCA1i, of BRCA2j, of BRCA3k, and on the disease status. As Parmigiani did, we factorize the conditional probability ρ ijk b of observing the disease history of member b, given the genetic status ijk, into two disease-specific term, one for breast cancer and one for ovary cancer (notice that at this point we can add other phenotypes).

where the meaning of indexes is: family member b, O = ovary, B = breast and

the ρ are defined in the following formula

where R ijk(a, g) is the cumulative risk at age a for the generation g and r ijk(a, g) is the age and birth cohort specific incidence.

To rewrite the formula used by Parmigiani in the case of 3 genes and for III degree relatives, we assign a label b to every family member and we define the following functions

m(b) | returns the label of the mother of b |

f(b) | returns the label of the father of b |

no(b) | returns the number of sons and daughters of b |

o l (b) l = 1, …, no(b) | returns the label of person l belonging to the offspring of b |

q(b) | returns the label of the mate of b |

ns(b) | returns the number of brothers and sisters of b |

s l (b) | l = 1, …, ns(b) returns the label of person l belonging to the sibling of b |

For instance, the label of the paternal grandmother of b will be f(m(b)).

We use the following notation to express multi-summation symbol

We rewrite the Parmigiani function d(m 1, m 2, f 1, f 2, n) in the case of three genes

It represents the probability of observing a determined clinical history in the offspring of b [formed by no(b) individuals] given the allele configuration (m 1, m 2, m 3) in the mother and (f 1, f 2, f 3) in the father (the temporary proband b could be either the mother or the father label). The function P[i|m, f] represents the probability to inherit i mutated alleles given m mutated alleles in the mother and f in the father following mendelian rules of gene transmission.

We can extend the d function in order to take into account two generations (sons and nephew) by defining

where \( \rho_{{q(o_{l} (b))}}^{{i_{q} j_{q} k_{q} }} \) is related to offspring mates (i.e. sons and daughter in law), if no information is available we consider ρ ijk q() = 1 for every ijk; the function P[i q , j q , k q ] represents the probability of the mate to have a certain allele configuration and it is directly related to the prevalence of the three mutations, that is

with

where f a is the allele frequency for gene BRCA a .

In case of three generations we can define the function

which incorporates the d2 function, and so on for further generations. Now we have solved how to “move down” in the family.

In order to write the functions to “move up” in the family we need to define the following function U b (o1, o2, o3) that represents the probability of observing the history of the parents and of the siblings of family member b given his gene status (o1, o2, o3)

The function P[i f , i m |o], used in the latter, represents the probability to find i f mutated alleles in the father and i m in the mother given o mutated alleles in the son or daughter. It is defined as follow using the Bayes theorem.

We have used the function ds where only the siblings of b (temporary proband) are taken into account;

It represents the probability of observing the history of siblings of b and of their offspring (up to two generations) given the genetic status of parents (m 1, m 2, m 3) and (f 1, f 2, f 3)

Note that in this case, even if the structure is the same of function d3, the label b is not referred to the parents as it was before but to temporary proband.

With the U function we can “move up” of one generation, but we want reach the great-grandparents so we need functions to do two more steps. We use U function to move from grandparents to great-grandparents and grandparents siblings; The U2 function defined by

is used to move from parents to grandparents, aunts and uncles and the function U3 defined by

is used to move from the proband to parents and proband’ s sibling.

Finally, the probability of observing the clinical family history given the genetic status (i, j, k) of the proband is

where ρ ijk p is refers to the proband personal clinical history, i m j m k m are refer to the genetic status of the proband’ s mate and ρ ijk q(p) to his history.

Finally according to the Bayes theorem the probability of observing mutation status [BRCA1, BRCA2, BRCA3] given the family history can be written

Appendix 2

The observed incidence rates in the general population ir all can be written as the sum of two or terms: the incidence rates for women carrying wild-type BRCA gene ir 0 time the prevalence of wild-type and the incidence rates ir 1 for women carrying BRCA mutation times the prevalence of mutation

where f is the allele frequency, (1 − f)2 is the wild-type prevalence and (f 2 + 2f(1 − f)) is the mutation prevalence. Because of the very low allele frequency we can approximate the latter by omitting the second order terms f 2.

In the case of three genes the latter becomes

The incidence rates for the wild-type BRCA is then

For instance we have simulated how mutation probability changes in a proband with breast cancer at different ages using respectively ir all and ir 0

Age | Mut. prob. using ir all | Mut. prob. using ir 0 |

|---|---|---|

20 | 0.452 | 0.837 |

25 | 0.243 | 0.323 |

30 | 0.141 | 0.166 |

40 | 0.071 | 0.077 |

50 | 0.033 | 0.035 |

60 | 0.028 | 0.030 |

70 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

We can note that the correction is important for younger ages when there is a considerable proportion of genetic cases.

Appendix 3

Software input

To estimate BRCA mutation probability, the COS software requires sex, current age or age at death, age at BC or OC diagnosis, age at diagnosis of second or contralateral BC, and age at any bilateral prophylactic mastectomy or oophorectomy in each family member.

The results of genetic testing can also be included (allowing researchers to calculate the mutation probability in untested family members).

These data are also required by BRCAPRO. Unlike BRCAPRO, however, the COS software additionally requires the date of birth of each family member (to allow for changing incidence and penetrance over generations).

Since data on the distant relatives of a proband are frequently incomplete, the COS software incorporates routines for the automatic imputation of missing information. These routines incorporate the following assumptions: that the interval between generations is 25 years, that BC and OC deaths occur 5 and 2 years, respectively, after diagnosis, and that life expectancy has increased from 65 years for people born before 1920 to 75 years for those born afterwards. A routine to automatically import family data from Progeny is available at http://www.progenygenetics.com/.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berrino, J., Berrino, F., Francisci, S. et al. Estimate of the penetrance of BRCA mutation and the COS software for the assessment of BRCA mutation probability. Familial Cancer 14, 117–128 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-014-9766-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-014-9766-8