Abstract

Research from the last four decades suggests that fairness plays an important role in economic transactions. However, the vast majority of this research investigates behavior in an environment where agents are fully informed. We develop a new experimental paradigm—nesting the widely used ultimatum game—and find that fairness has less impact on outcomes when agents are less informed. As we remove information, offers become less generous and unfair offers are more likely to be accepted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

That seminal work explores a setting where the pie is relatively more valuable to one of the two parties (i.e. the tokens that the subjects split are worth 3 times more for one subject than the other), allowing for self-serving definitions of fairness to arise. We explore a simpler setting where the pie being split is equally valuable to both parties.

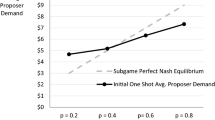

These results focus on the last 10 rounds of the game, after subjects gain experience. However, results from all 30 rounds show consistent findings.

In related work, Klempt et al. (2019) analyzes the effects of asymmetric information when either the proposer or the responder is better informed in the ultimatum and dictator game. See also Siegel and Fouraker (1960), which explored bilateral bargaining games in a different experimental paradigm but also considered the role of information on outcomes.

Another related literature builds off of the “acquiring-a-company” game (Samuelson & Bazerman, 1984) and explores the impact of information available to buyers and sellers (Güth et al., 2017, 2019). Because that game was designed to explore the winner’s curse, however, it typically involves additional uncertainty for one or both parties, such as parties not knowing their own payoff from transacting.

Three sessions of each treatment were run at Wharton and two sessions of each treatment were run at Stanford. As shown in Appendix Table B6, there were no substantial differences by location and so we pool the data in what follows.

While rare, this type of overly generous offer is more likely to occur when buyers are uninformed of the seller’s cost and so are unlikely to know that they have offered over half of the pie. When the buyer is informed, less than 2.5% of offers are overly generous.

We define two alternative definitions of inequality share that differently handle the small number of cases where buyers are overly generous and offer the seller a larger share of the pie than they keep. These offers can be seen as increasing inequality at the transactional level or reducing inequality at the market level. Absolute Inequality Share \(=\frac{| \pi _B - \pi _S|}{V-C}\) is the absolute difference between the buyer and seller’s earnings divided by the total surplus and treats offers that give the majority of the surplus to the seller as increasing inequality. Difference Inequality Share \(=\frac{ \pi _B - \pi _S}{V-C}\) is the difference in earnings between buyers and sellers divided by the total surplus, which is allowed to be negative and thus treats offers that give the majority of the surplus to the seller as decreasing inequality.

Note that since the surplus available for a given transaction, \(V-C\), differs across rounds, we report all outcomes in terms of the fraction of surplus that was available in a given round.

Appendix Table B1 shows corresponding results for all 30 rounds, the first 10 rounds, and the last 10 rounds (replicating the results in Table 2). The regressions that we use to assess significance in Appendix Table B1 are shown in Appendix Tables B2–B4. We find differences in play between the first 10 and last 10 rounds: across all treatments, Buyer Share, Seller Share, and Total Share increase as subjects play more rounds while Rejection Rate, which is equal to \(1-\)Total Share, falls. We confirm there are significant differences in a regression framework, shown in Appendix Table B5, which compares outcomes in the first 10 rounds and the last 10 rounds.

Appendix Table B6 presents results for participants at Wharton and Stanford separately and shows that differences between participants at the two schools are not statistically significant. Appendix Table B7 shows that results are consistent and significant using session clusters. Appendix Table B8 shows that our results on inequality from Table 2 are robust to using the two alternative measures of inequality.

Appendix Figure B1 summarizes these results and points to where these results are documented.

These differences are consistent and statistically significant when examining all 30 rounds of the game (see Appendix Figure B2 and the left panel of Appendix Table B12).

This is consistent with work by Ockenfels and Werner (2012) in which dictators “hide behind the small cake” when the size of the pie is unknown. While our setting does not have a reputational component because identities are not known, this result may also be consistent with a model of reputation formation (Camerer & Weigelt, 1988; Jung et al., 1994; Embrey et al., 2014).

We used a Becker–DeGroot–Marschak (BDM) method for binary outcomes. To supplement the BDM instructions, we also explicitly emphasized for subjects that the method incentivized honest reporting of beliefs (see instructions in Appendix Section C).

In this section, we focus on buyer beliefs conditional on offers between 20 and 60 experimental units, where most of our data is concentrated. Figure B4 in the appendix presents the cumulative distribution functions of offers used to elicit beliefs and shows that more than 99% of offers are between 20 and 60 experimental units.

The data in panel (c) is slightly noisier, but beliefs in the Neither Knows treatment do not vary much by value and are slightly above acceptance probability beliefs in the Seller Knows treatment when low offers are made.

If each offer corresponded to a certain buyer’s value (i.e., no pooling) then we would not have seen differences by treatment.

See Appendix Table B13 for regression results across all 30 rounds and the last 10 rounds.

Appendix Figure B5 replicates this graph for all 30 rounds and the left panel of Appendix Table B13 shows the corresponding regression results.

We used a Becker–DeGroot–Marschak (BDM) method for binary outcomes. To supplement the BDM instructions, we also explicitly emphasized for subjects that the method incentivized honest reporting of beliefs (see instructions in Appendix Section C).

While not our focus here, exploring cases where information acquisition is private information is an exciting avenue for future work. For example, Roth and Keith Murnighan (1982) shows more disagreement in a lottery game when the information setting itself is not common knowledge.

References

Andersen, S., Ertaç, S., Gneezy, U., Hoffman, M., & List, J. A. (2011). Stakes matter in ultimatum games. American Economic Review, 101, 3427–3439.

Andreoni, J., & Douglas Bernheim, B. (2009). Social image and the 50–50 norm: A theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica, 77, 1607–1636.

Bahry, D. L., & Wilson, R. K. (2006). Confusion or fairness in the field? Rejections in the ultimatum game under the strategy method. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60, 37–54.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2016). Mindful economics: The production, consumption, and value of beliefs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30, 141–64.

Bereby-Meyer, Y., & Niederle, M. (2005). Fairness in bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 56, 173–186.

Binmore, K., Shaked, A., & Sutton, J. (1985). Testing noncooperative bargaining theory: A preliminary study. American Economic Review, 75, 1178–80.

Bolton, G., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). Erc: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. American Economic Review, 90, 166–193.

Brañas-Garza, P., Cobo-Reyes, R., & Domínguez, A. (2006). “si él lo necesita’’: Gypsy fairness in vallecas. Experimental Economics, 9, 253–264.

Camerer, C., & Weigelt, K. (1988). Experimental tests of a sequential equilibrium reputation model. Econometrica, 56, 1–36.

Carpenter, J. (2010). Social preferences (pp. 247–252). Palgrave Macmillan.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 817–869.

Cochard, F., Le Gallo, J., Georgantzis, N., & Tisserand, J.-C. (2021). Social preferences across different populations: Meta-analyses on the ultimatum game and dictator game. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 90, 101613.

Croson, R. (1996). Information in ultimatum games: An experimental study. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 30, 197–212.

Dana, J., Weber, R. A., & Kuang, J. X. (2007). Exploiting moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Economic Theory, 33, 67–80.

Danková, K., Morita, H., Servátka, M., & Zhang, L. (2022). Fairness concerns and job assignment to positions with different surplus. Southern Economic Journal, 88, 1490–1516.

Declerck, C. H., Kiyonari, T., & Boone, C. (2009). Why do responders reject unequal offers in the ultimatum game? An experimental study on the role of perceiving interdependence. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30, 335–343.

Dhami, S., Manifold, E., & Nowaihi, A. (2021). Identity and redistribution: Theory and evidence. Economica, 88, 499–531.

Embrey, M., Fréchette, G. R., & Lehrer, S. F. (2014). Bargaining and reputation: An experiment on bargaining in the presence of behavioural types. The Review of Economic Studies, 82, 608–631.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 817–868.

Griffin, J., Nickerson, D., & Wozniak, A. (2012). Racial differences in inequality aversion: Evidence from real world respondents in the ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 84, 600–617.

Güth, W., Pull, K., Stadler, M., & Zaby, A. (2019). Compulsory disclosure of private information: Theoretical and experimental results for the acquiring-a-company game. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE), 175, 502–523.

Güth, W., Pull, K., Stadler, M., & Zaby, A. K. (2017). Blindfolded vs. informed ultimatum bargaining—A theoretical and experimental analysis. German Economic Review, 18, 444–467.

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3, 367–388.

Güth, W., & van Damme, E. (1998). Information, strategic behavior, and fairness in ultimatum bargaining: An experimental study. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 42, 227–247.

Harstad, R., & Nagel, R. (2004). Ultimamtum games with incomplete information on the side of the prosper: An experimental study. Cuadernos de economía: Spanish Journal of Economics and Finance, 27, 37–74.

Ho, T.-H., & Xuanming, S. (2009). Peer-induced fairness in games. American Economic Review, 99, 2022–49.

Hoffman, E., & Spitzer, M. L. (1982). The coase theorem: Some experimental tests. Journal of Law and Economics, 25, 73–98.

Jung, Y. J., Kagel, J. H., & Levin, D. (1994). On the existence of predatory pricing: An experimental study of reputation and entry deterrence in the chain-store game. The RAND Journal of Economics, 25, 72–93.

Kagel, J., Kim, C., & Moser, D. (1996). Fairness in ultimatum games with asymmetric information and asymmetric payoffs. Games and Economic Behavior, 13, 100–110.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness and the assumptions of economics. The Journal of Business, 59, 285–300.

Keniston, D., Larsen, B.J., Li, S., Prescott, J.J., Silveira, B.S. & Yu, C. (2021). Fairness in incomplete information bargaining: Theory and widespread evidence from the field.

Klempt, C., Pull, K., & Stadler, M. (2019). Asymmetric information in simple bargaining games: An experimental study. German Economic Review, 20, 29–51.

Lee, C. C., & Lau, W. K. (2013). Information in repeated ultimatum game with unknown pie size. Economics Research International, 2013, 1–8.

Lee, K., & Shahriar, Q. (2017). Fairness, one’s source of income, and others’ decisions: An ultimatum game experiment. Managerial and Decision Economics, 38, 423–431.

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2007). What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences reveal about the real world? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 153–174.

Liberman, V., Samuels, S. M., & Ross, L. (2004). The name of the game: Predictive power of reputations versus situational labels in determining prisoner’s dilemma game moves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1175–1185.

Mallucci, P., Diana Yan, W., & Cui, T. H. (2019). Social motives in bilateral bargaining games: How power changes perceptions of fairness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 166, 138–152.

Mitzkewitz, M., & Nagel, R. (1993). Experimental results on ultimatum games with incomplete information. International Journal of Game Theory, 22, 171–98.

Möbius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2022). Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. Management Science, 68, 7793–7817.

Neelin, J., Sonnenschein, H., & Spiegel, M. (1988). A further test of noncooperative bargaining theory: Comment. American Economic Review, 78, 824–836.

Ochs, J., & Roth, A. E. (1989). An experimental study of sequential bargaining. American Economic Review, 79, 355–384.

Ockenfels, A., & Werner, P. (2012). “hiding behind a small cake’’ in a newspaper dictator game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 82, 82–85.

Poulsen, A. U., & Tan, J. H. W. (2007). Information acquisition in the ultimatum game: An experimental study. Experimental Economics, 10, 391–409.

Prasnikar, V., & Roth, A. (1992). Considerations of fairness and strategy: Experimental data from sequential games. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 865–888.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating Fairness into Game Theory and Economics. American Economic Review, 83, 1281–1302.

Rapoport, A., Sundali, J. A., & Seale, D. A. (1996). Ultimatums in two-person bargaining with one-sided uncertainty: Demand games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 30, 173–196.

Roth, A. E., Malouf, M. W. K., & Keith Murnighan, J. (1981). Sociological versus strategic factors in bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2, 153–177.

Roth, A. E., & Keith Murnighan, J. (1982). The role of information in bargaining: An experimental study. Econometrica, 50, 1123–1142.

Samuelson, W., & Bazerman, M.H. (1984). The winner’s curse in bilateral negotiations.

Schmitt, P. (2004). On perceptions of fairness: The role of valuations, outside options, and information in ultimatum bargaining games. Experimental Economics, 7, 49–73.

Selten, R. (1978). The equity principle in economic behavior (pp. 289–301). Springer.

Siegel, S., & Fouraker, L. (1960). Bargaining and group decision making: Experiments in bilateral monopoly. McGraw-Hill.

Straub, P. G., & Murnighan, J. (1995). An experimental investigation of ultimatum games: information, fairness, expectations, and lowest acceptable offers. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27, 345–364.

Stüber, R. (2020). The benefit of the doubt: Willful ignorance and altruistic punishment. Experimental Economics, 23, 848–872.

Voslinsky, A., Lahav, Y., & Azar, O. H. (2021). Does a second offer that becomes irrelevant affect fairness perceptions and willingness to accept in the ultimatum game? Judgment and Decision Making, 16, 743.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Funding for the study came from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, the Wharton Behavioral Lab, and Stanford University.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Kessler, J.B. & Niederle, M. Fairness has less impact when agents are less informed. Exp Econ 27, 155–174 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-023-09795-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-023-09795-w