Abstract

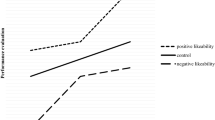

This paper reports findings of a laboratory experiment, which explores how reported self-assessment regarding the own relative performance is perceived by others. In particular, I investigate whether overconfident or underconfident subjects are considered as more likeable, and who of the two is expected to win in a tournament, thereby controlling for performance. Underconfidence beats overconfidence in both respects. Underconfident subjects are rewarded significantly more often than overconfident subjects, and are significantly more often expected to win. Subjects being less convinced of their performance are taken as more congenial and are expected to be more ambitious to improve, whereas overconfident subjects are rather expected to rest on their high beliefs. While subjects do not anticipate the stronger performance signal of underconfidence, they anticipate its higher sympathy value. The comparison to a non-strategic setting shows that men strategically deflate their self-assessment to be rewarded by others. Women, in contrast, either do not deflate their self-assessment or do so even in non-strategic situations, a behavior that might be driven by non-monetary image concerns of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Svenson (1981), e.g., shows that more than 50 % of participants (77 % in a Swedish and 88 % in a US study) report to drive more safely than the median, taking this result as evidence for overconfidence. Other studies demonstrating the better-than-average effect are Alicke (1985), Dunning et al. (1989) and Messick et al. (1985).

In laboratory experiments Hoelzl and Rustichini (2005) show that people’s choice behavior (competition vs. lottery) is underconfident when the task is non-familiar. Krueger (1999) and Moore and Cain (2007) also find that people tend to be underconfident rather than overconfident when the task is (perceived as) difficult. Clark and Friesen (2009) test for overconfidence in people’s forecasts of their absolute and relative performance and observe a correct self-assessment or underconfidence more often than overconfidence.

For example Niederle and Vesterlund (2007) show that overconfidence makes bad performing men selecting competitive payment schemes too often (regarding payoff maximization), and that underconfidence makes high performing women selecting competitive payment schemes too little.

This is in line with women’s shame of overestimation observed by the experimental study by Ludwig and Thoma (2012).

Note that the accuracy of agents’ self-assessment is still observable in the control treatments, but the agents do not have a monetary incentive to be chosen.

Also compare Charness et al. (2012) who use this argumentation to explain overconfidence in non-strategic competitive settings.

Another study claiming that individuals inflate their reported self-assessment due to non-monetary image concerns is Burks et al. (2013). In a large survey with male truck drivers, they find a correlation between how much one cares about his image and overconfidence, consequently claiming that “overconfidence is a social signaling bias”.

In an experimental study Montinari et al. (2012) observe that the ex ante low ability type is chosen more often, as he is expected to exert more effort when receiving a fixed wage. However, the reason is a higher expected reciprocity when hiring the low ability type, which is absent in my study, as agents do not receive a fixed wage and do not learn whether they’ve been chosen or not until the end of the experiment.

Two agents receive the same rank to have the same initial position for their self-assessment.

Answers in the follow-up questionnaire show that principals nevertheless expected the agents to state their true belief about their relative ranks.

This choice actually became relevant for 20 out of 56 principals.

On subjects’ screens the situations were listed in a different order and I varied whether the more or less self-confident agent was listed first, what actually did not influence results.

Besides my interest in whether accuracy is favored over over- and underconfidence, I picked the 12 different situations to cover the most realistic outcomes. Using the SVM instead of showing the actual deviations to the principal decreases the number of sessions needed and allows for a cleaner data analysis.

This situation became relevant in 8 out of 56 situations.

Results go in the same direction when excluding hypothetical choices, but are less significant due to fewer observations. The separated data is listed in the Appendix.

The results are robust to OLS regressions.

To elicit risk preferences, individuals indicated on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 whether they are willing to take risks (or try to avoid risks). 0 represented a very weak willingness to take risks, while 10 represented a strong willingness to take risks. Dohmen et al. (2011) show that this general risk question is a good predictor of actual risk-taking behavior.

The results are robust to OLS regressions.

Seven out of 15 agents stating the worse rank win task 2 in PERF and 7 out of 12 in PERF-CON. 10 pairs of agents state the same rank.

To calculate the simulated ranks, I ran Monte-Carlo simulations, in which I randomly drew 500,000 groups consisting of 15 participants out of the performance distribution of all agents (with replacement). I then calculated for any given performance level the rank within each simulated group. The simulated rank equals the mode of all 500,000 calculated ranks.

I cannot confirm the highly debated finding that subjects are overconfident. In this experiment, 22 % of agents estimate their rank correctly, 35 % have a deviation of +/\(-\)1 rank, 25 % have a deviation of +/\(-\)2 ranks and only 9 % of subjects overestimate their rank by 3 or 4 ranks. In comparison also 9 % underestimate their rank by 3–5 ranks.

Note that simulated ranks in PERF are lower than in SYMP. As participants on lower ranks are more likely to overestimate themselves, the difference across treatments might not be due to a treatment difference, but only due to a performance difference and the limited scale. To take care of this issue I conduct ordered probit regressions below.

The results are robust when conducting OLS regressions.

References

Akerlof, G. A., & Dickens, W. T. (1982). Labor contracts as partial gift exchange. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 97(4), 543–569.

Alicke, M. D. (1985). Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1621–1630.

Balafoutas, L., & Sutter, M. (2012). Affirmative action policies promote women and do not harm efficiency in the lab. Science, 335(6068), 579–582.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2002). Affirmative action policies promote women and do not harm efficiency in the lab. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 871–915.

Benoît, J.-P., & Dubra, J. (2011). Apparent overconfidence. Econometrica, 79(5), 1591–1625.

Beyer, S. (1990). Gender differences in the accuracy of self-evaluations of performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 960–970.

Beyer, S., & Bowden, E. M. (1997). Gender differences in self-perceptions: Convergent evidence from three measures of accuracy and bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 157–172.

Brocas, I., & Carrillo, J. D. (2000). The value of information when preferences are dynamically inconsistent. European Economic Review, 44, 1104–1115.

Brody, L. R. (1997). Gender and emotion: Beyond stereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 53, 369–394.

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Parker, J. A. (2005). Optimal expectations. American Economic Review, 95(4), 1092–1118.

Burks, S. V., Carpenter, J. P., Goette, L., & Rustichini, A. (2013). Overconfidence and social signalling. Review of Economic Studies, 80(3), 949–983.

Camerer, C., & Lovallo, D. (1999). Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. American Economic Review, 89(1), 306–318.

Caplin, A., & Leahy, J. (2001). Psychological expected utility theory and anticipatory feelings. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 55–79.

Charness, G., Rustichini, A., & Van de Ven, J. (2012). Self-confidence and strategic behavior. Mimeo.

Clark, J., & Friesen, L. (2009). Overconfidence in forecasts of own performance: An experimental study. Economic Journal, 119(534), 229–251.

Compte, O., & Postlewaite, A. (2004). Confidence-enhanced performance. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1536–1557.

Datta Gupta, N., Poulsen, A., & Villeval, M. C. (2013). Gender matching and competitiveness: Experimental evidence. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 816–835.

Dohmen, T., & Falk, A. (2011). Performance pay and multi-dimensional sorting: Productivity, preferences and gender. American Economic Review, 101(2), 556–590.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Dunning, D., Meyerowitz, J. A., & Holzberg, A. D. (1989). Ambiguity and self-evaluation: The role of idiosyncratic trait definitions in self-serving assessments of ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1082–1090.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ewers, M., & Zimmermann, F. (2012). Image and misreporting. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6425.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for readymade economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Gervais, S., & Goldstein, I. (2007). The positive effects of biased self-perceptions in firms. Review of Finance, 11(3), 453–496.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments. In K. Kremer & V. Macho (Eds.), Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen 2003, GWDG Bericht 63 (pp. 79–93). Göttingen: Gesellschaft für Wissenschaftliche Datenverarbeitung.

Grossman, M., & Wood, W. (1993). Gender differences in intensity of emotional experience: A social role interpretation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1010–1022.

Hoelzl, E., & Rustichini, A. (2005). Overconfident: Do you put your money on it? Economic Journal, 115, 305–318.

Koszegi, B. (2006). Ego utility, overconfidence, and task choice. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(4), 673–707.

Krueger, J. I. (1999). Lake Wobegon be gone! The below-average effect and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(2), 221–232.

Larrick, R. P., Burson, K. A., & Soll, J. B. (2007). Social comparison and confidence: When thinking you’re better than average predicts overconfidence (and when it does not). Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102, 76–94.

Ludwig, S., & Thoma, C. (2012). Do women have more shame than men? An experiment on self-assessment and the shame of overestimating oneself. Munich Discussion Paper 2012-15.

Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2005). CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance, 60(6), 2661–2700.

Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2008). Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. Journal of Financial Economics, 89, 20–43.

Messick, D. M., Bloom, S., Boldizar, J. P., & Samuelson, C. D. (1985). Why we are fairer than others? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 480–500.

Möbius, M. M., Niederle, M., Niehaus, P., & Rosenblat, T. S. (2012). Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. Mimeo.

Montinari, N., Nicolo, A., & Oexl, R. (2012). Mediocrity and induced reciprocity. Jena Economic Research Papers 2012-053.

Moore, D. A., & Cain, D. M. (2007). Overconfidence and underconfidence: When and why people underestimate (and overestimate) the competition. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 197–213.

Moore, D., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502–517.

Myerson, R. (1991). Game theory: Analysis of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Niederle, M., Segal, C., & Vesterlund, L. (2013). How costly is diversity? Affirmative action in light of gender differences in competitiveness. Management Science, 59(1), 1–16.

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101.

Niederle, M., & Yestrumskas, A. H. (2008). Gender differences in seeking challenges: The role of institutions. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 3922.

Odean, T. (1999). Do investors trade too much? American Economic Review, 89, 1279–1298.

Raven, J., Raven, J. C., & Court, J. H. (2003). Raven’s Progressive Matrices und Vocabulary Scales. Grundlagenmanual. Frankfurt: Pearson Assessment.

Reuben, E., Rey-Biel, P., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2012). The emergence of male leadership in competitive environments. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 83(1), 111–117.

Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk-factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 629–645.

Samuelson, L. (2001). Analogies, adaptation, and anomalies. Journal of Economic Theory, 97(2), 320–366.

Santos-Pinto, L. (2008). Positive self-image and incentives in organisations. Economic Journal, 118(531), 1315–1332.

Sautmann, A. (2013). Contracts for agents with biased beliefs: Some theory and an experiment. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 5(3), 124–156.

Svenson, O. (1981). Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica, 47, 143–148.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Martin Kocher, Sandra Ludwig, Ernesto Reuben, Klaus Schmidt, Marta Serra-Garcia, Sebastian Strasser, Ferdinand Vieider, participants of the MELESSA Brown Bag Seminar at the University of Munich for helpful comments and discussions. Financial support from Sonderforschungsbereich (SFB)/Transregio (TR) 15 is gratefully acknowledged. For providing laboratory resources I kindly thank MELESSA of the University of Munich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thoma, C. Under- versus overconfidence: an experiment on how others perceive a biased self-assessment. Exp Econ 19, 218–239 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9435-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9435-2