Abstract

This study evaluates the impact of introducing the Maternity Capital (MC) program—a child subsidy of 250,000 Rub (7,150 euros or 10,000 USD, in 2007)—provided to mothers giving birth to/adopting a second or subsequent child since January 2007. Eligible Russian families could use this subsidy to improve family housing conditions, fund child’s education/childcare, or invest in the mother’s retirement fund. This study evaluates the impact of MC eligibility on various child health and developmental outcomes, household consumption patterns, and housing quality. Using data from the representative Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey 2010–2017, I tested regression discontinuity models and found that MC eligibility may have led to a small improvement in child health status, which could be explained by improved housing conditions, particularly in rural areas. However, children living in MC-eligible families were also more likely to report reduced socialisation. Heterogeneity analysis by child gender, household poverty status, and urban/rural residence suggests that MC incentives may have had a differential impact on some analysed outcomes. Results are robust to different polynomial and nonparametric RDD specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction and Literature Review

Faced with an aging population and the global trend of decreasing fertility, many governments increasingly regard pro-natalist policies and their impact on households as an issue of primary concern. At the beginning of 2007, the Russian government implemented a reform whereby second and subsequent childbirths/child adoptions were incentivised by a government-sponsored subsidy of around 10,000 USD. This subsidy, called the Maternity Capital (MC), could be spent on three eligible purposes: improving housing conditions, providing education/childcare to children, or investing in the mother’s state pension fund account. This study aims to evaluate how this pro-natalist measure affected multiple measures of child health and well-being, parents’ willingness to invest in child human capital, as well as major household consumption patterns and household financial behaviour.

The results presented in this study indicate that, at the aggregate level, MC eligibility did not significantly affect the patterns of time spent by children, their well-being outcomes, or household diets. Model estimates suggest that children living in MC-eligible households may have benefited from a reduction in the number of chronic health conditions. This effect seems to be more pronounced in rural areas, where MC-eligible families reported a significant improvement in access to essential amenities and public utilities (e.g. central heating and sewerage). On the other hand, results also indicate that children in MC-eligible households could face socialisation issues that manifested themselves, for example, by a more than 30% decrease in the likelihood that the child will be reported by their parents to see their friends at least three times a week. This effect appears to be driven primarily by wealthier households and seems to affect boys more strongly than girls.

Regarding household-level outcomes, MC-eligible families were estimated to make higher bank loan monthly payments, particularly wealthier households and households living in urban areas. Their consumption and spending profiles (e.g. higher spending on essential items and utilities, reduced expenditures on clothing) are consistent with using the MC subsidy to improve housing conditions.

The contribution of our study to the existing economics literature is threefold. First, it studies a broad set of child well-being outcomes, some of which, to the best of my knowledge, have never been investigated in the economics literature. In particular, no earlier study systematically looked at the impact of child subsidies on time spending patterns by children. Some of these metrics, such as time spent on extracurricular study and arts, serve as likely proxies of parental willingness to invest in the child’s human capital. Second, this paper is one of the very few studies that address the link between child subsidies and household diets, household financial behaviour, and housing conditions, which are believed to have long-lasting effects on children’s health and development. Lastly, our study fills a relative lack of research on the impact of pro-natalist reforms in middle-income transitioning countries, whose distinct features (e.g. weaker social security, a higher degree of uncertainty with respect to future income) may create incentives different from those commonly observed in developed countries.

Previous studies on the MC concentrated on its impact on female fertility. For example, Slonimczyk and Yurko (2014) tested a dynamic stochastic model of fertility, wherein women simultaneously make decisions as to whether to have a child and with regard to their participation in the labour market. The authors concluded that the MC subsidy more strongly affected the second childbirths as opposed to the first childbirths, as well as married women. However, the authors did not find sufficient evidence for a differential impact of MC on fertility based on women’s current employment status or urban/rural residence.

As far as analysed outcomes as concerned, few studies concentrated specifically on the effects of child subsidies on child well-being. In 2004, the Australian government introduced a universal $3000 lump-sum all-purpose cash transfer to Australian families who had childbirth or adopted a child, called a Baby Bonus. Similar to the MC, this subsidy was not means-tested. This reform was studied by Gaitz and Schurer (2017) and Deutscher and Breunig (2018), who, using similar difference-in-difference designs and data sources, concluded the reform had little effect on various educational, physiological, and physical health outcomes of pre-school children.

As for child health indicators, empirical research tends to support the idea that material investments made in early childhood could generate benefits in terms of health outcomes (Baughman & Duchovny, 2016; Case et al., 2002; Currie, 2009). Similar effects are observed for child cognitive development and educational attainment, as evidenced, for example, by Dahl and Lochner (2012), who find that the introduction of tax benefits in the USA between 1993 and 1997 helped raise scores in reading and math tests taken by children living in affected households.

The remaining parts of this paper are organised as follows: Section 2 describes the Maternity Capital eligibility conditions and describes the Russian institutional context. Section 3 describes RLMS data used in this study, and Sect. 4 explains the empirical design and provides the main estimation results. Heterogeneity analysis is conducted in Sect. 5. Section 6 discusses the contribution, limitations, and external validity of this study and concludes.

2 Maternity Capital Institutional Context

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia entered an acute economic and social crisis that profoundly changed the demographic dynamics of the country. Lack of access to essential goods such as food, disrupted supply chains, mass unemployment, and underfunded healthcare led to a simultaneous increase in mortality and a drastic fall in fertility. To illustrate, in one decade, the total fertility rate in Russia fell from 2.06 in 1989 to an estimated 1.16 in 1999.

In the 2000s, Russia’s economic situation revived, which was accompanied by steady growth in disposable income and an improved living standard. In an attempt to boost falling fertility rates, in January 2007 the Russian government started funding the subsidy called Maternity Capital targeted at mothers with multiple children.

According to eligibility conditions, MC can be claimed by any individual holding Russian citizenship and falling into one of the two categories:

-

1.

women who gave birth to or adopted a second or consecutive child after 1 January 2007

-

2.

men who from 1 January 2007 onward is recognised as the sole adopter of a second, third, or subsequent children, and who did not previously use his right to the Maternity Capital

During the period analysed in this study, MC funds were allowed to be used towards improving housing conditions (through co-funding purchase of the real estate, paying part of the mortgage or repairing/improving current housing), paying for education/childcare expenses of (any) child in the family aged 3–25 years old, and investing in mother’s pension fund.

The MC subsidy certificate has to be granted to an adult family member. For simplicity, I will further refer to potential MC recipients as mothers, leaving the male population outside the scope of the analysis. In general, there is a 3-year delay before an MC subsidy can be issued. However, it does not apply to cases where funds are used to make a downpayment, or fund part of a mortgage, in which case the MC subsidy can be used almost immediately after the eligibility criteria are met. MC funds may be split between multiple purposes and beneficiaries.

In a broader context, the size of MC—250 000 Rubles in 2007 (equivalent to around $9800 US in 2007)—is a very significant sum of money for most Russian families. To put it into perspective, in 2011, the average salary in Russia was estimated to be 23369 Rubles (725 USD in 2011 prices), while the maximum monthly unemployment benefit was set at 4900 Rubles (163 USD in 2011 prices, less than 1/4 of the average salary amount). Thus, MC certificates are approximately worth one year’s average salary amount (ROSSTAT, 2020).

In general, Russian political institutions are considered to be lacking in accountability and the rule of law. Partially as a result of this, a relatively small fraction of the Russian population claims to have trust in public institutions, be they federal or local, executive, legislative or judicial, with one major exception from this rule being the Russian president (Levada Center, 2014). The lack of trust in Russian state institutions plausibly explains the unwillingness of MC-eligible Russian women to invest the subsidy in the pension fund.

3 Data and Descriptive Statistics

The primary data source for this study is the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey (RLMS). It is a panel survey conducted every year since 1994 for a representative sample of both Russian individuals and households. RLMS features three core modules: adults, children, and households. The resulting datasets contain an extremely rich set of variables that cover virtually all areas of respondents’ lives (e.g. employment, income, health, education, attitudes towards social issues, and family relationships). RLMS interviews occur every year at the respondent’s home, normally from October to January the following year, as long as participating families continue to live at the same address and are willing to participate in the study.

In total, 16 child outcomes related to health and development, material conditions, and the degree of parental involvement in child upbringing were analysed to evaluate the impact of MC on child well-being. In addition, this analysis is complemented with a household-level study of the MC impact on dietary habits, spending patterns, financial behaviour, and housing conditions, which are likely to affect all family members directly or through spillover effects.

The main analytical sample is restricted to second children born between 2004 and 2009 (i.e. three years before and after the introduction of Maternity capital in 2007) and aged from 6 to 8 years old, whose parents were surveyed in RLMS waves from 2010 to 2017 and living in households with two children. The observations were collected from RLMS waves from 2010 to 2017, with the median year of 2013. However, since the full analytical sample has a 3-year window around the cut-off date of 1 January 2007, the measurements for MC-eligible and MC-ineligible families are separated by, on average, three years (median survey years are 2012 for MC-ineligible families, and 2015 for MC-ineligible ones). A given child and the corresponding household can be observed a maximum of 3 times, when the child is 6, 7, and 8 years old. However, due to sample attrition and restricting the analytical sample only to the cohort of children aged 6–8 and born in 2004–2009, the average number of times a given child/household appears in the sample is 2.26 (25.3%- 1 time, 23.3% - 2 times, 51.4% -3 times). The annualised attrition rate (i.e. the average rate at which children aged 6-7 do not appear in the next RLMS wave, for RLMS waves 2010-2016) in the analysed sample is 19.2%. Additional tables on the time distribution of observations, as well as other descriptive statistics, are provided in Tables 8, 9, and 10 of Appendix 2.

Descriptive statistics on the sample of second children and both MC-eligible and MC-ineligible subgroups are provided in Tables 1 and 2. In total, the analytical sample contains 1047 observations (i.e. a child observed in a given RLMS wave, who could be observed in up to three waves in total), 515 of whom (49.2%) represent children who were born after the MC program was introduced in January 2007. Children born before and after 1 January 2007 had broadly similar characteristics in many health and developmental outcomes. In particular, participating respondents considered that their children were in good/excellent health in around 77% of cases, with an average of 0.3 chronic medical conditions reported per child. However, MC-eligible families also report a slightly higher percentage of boys than girls. After school classes, many children were also involved in extracurricular educational activities, such as private lessons, art classes and extracurricular sports/physical activities (14, 120 and 220 minutes per week on average, respectively).

As for mothers, their average age in the analytical sample is around 36.5 years, with 14.5% of observations living in households with only one parent. On average, MC-eligible and MC-ineligible mothers also shared similar characteristics regarding their ethnicity, urban/rural residency, and self-reported alcohol consumption.

At the same time, there is suggestive evidence that the demographics of mothers who responded to MC stimuli may not completely mirror cohort averages. In particular, MC-eligible families reported, on average, a slightly higher age (37 vs. 36.3 years old) and a higher rate of graduating from a higher education institution (34% vs. 26% in MC-eligible and MC-ineligible families, respectively). This likely results from the fact that higher education graduation rates have been increasing in Russia in the 2010s and the fact that the parents of the 2007–2009 birth cohort, on average, are observed later in the analytical 2010–2017 period.

As for household spending patterns, MC-eligible and MC-ineligible families reported on similar average levels of essential expenditures. However, MC-eligible families were less likely to report the purchase of a durable good (32.9% vs. 41.2%) and had lower spending on clothes (i.e. 4.1K Rub/135 USD vs. 4.7K Rub/155 USD, in 2011 prices) and on non-essential items (i.e. 4.2K Rub/140 USD vs. 6.0K Rub/200 USD, in 2011 prices). In the meantime, MC-eligible households had a heavier monthly bank loan burden (i.e. 4.7K Rub/155 USD vs. 3.7K Rub/125 USD, in 2011 prices) and lower rates of taking out a consumer loan or lending to private individuals in the last one year.

Overall, MC-eligible and MC-ineligible families reported broadly similar diets, with minor differences in fruit and refined sugar consumption. Finally, in terms of reported housing conditions, the vast majority (89%) of Russian families own their housing.

More detailed definitions of child outcomes, spending and consumption categories, and other variables used in this study are provided in Appendix 1.

4 Empirical Strategy and Main Results

The empirical strategy of this study MC relies on the fact that MC eligibility is dependent on the precise cut-off date of 1 January 2007. After this date, any family giving birth to second or subsequent children was automatically given MC rights. To ensure that results are comparable among analysed households, I concentrate solely on families with two children, who constitute by far the most common case among MC-eligible families.

The prospect of the MC reform was first announced during the presidential address to the members of the Russian parliament in May 2006. However, no precise timeline for MC implementation was given, which makes it highly unlikely that the fertility decisions of Russians of their reproductive age were affected at this point. Aggregate official figures on childbirth by month published in Demoscope (2019) also suggest that the MC effect on fertility started to take shape only in August 2007.

The focus of the strategy consists in comparing the outcomes of interest in the immediate neighbourhood of the intervention cut-off date, where, theoretically, any observed differences in outcome variables must be solely attributable to the intervention due to near-complete treatment randomisation. To this end, I select children born within 12-, 24-, and 36-month windows around the intervention cut-off date.

It appears possible that mothers’ fertility responses to the MC were not identical across observed socio-demographic characteristics, especially several months/years after the introduction of the MC. Slonimczyk and Yurko (2014) point to the possibility that, for example, married and poorer/less-educated women reacted more strongly to MC incentives but the differences they found were very modest and insignificant. Appendix 2 provides descriptive statistics by the year of birth, and Appendixes 4 and 5 also test RDD models for mother and household covariates around the cut-offs of January and August 2007, respectively. The results are suggestive of the possibility of self-selection into MC based on, for example, the higher education status, which in all likelihood could only affect births that occurred at least 8–9 months after the introduction of the MC.

To estimate the effect of MC on child outcomes, I test regression discontinuity models of the functional form:

where for a child i born in year-month t and observed in RLMS survey wave p, \(Outcome_{ip}\) is the analysed outcome of interest, \(trend_{t}\) is a linear trend for the month of birth relative to January 2007 and \(trend_{t}^{k}\) is its exponent of the \(k^{th}\) degree; \(post_t\) is an indicator variable for births occurring on and after the 1 January 2007, \(X_{ip}\) is a vector of child-specific controls including child’s age (in months), sex and urban (i.e. city or regional centre)Footnote 1; \(Z_{ip}\) is a vector of mother and household-specific controls, including mother’s age (in years) and a set of dummies indicating higher education, excellent/good health status, non-Russian ethnicity, self-declared poverty status, frequent alcohol consumption and the indicator that she raises a child as a single parent; \(\nu _p\) are RLMS wave dummies; \(\epsilon _{ip}\) is a random error term. To account for potential intertemporal and intraregional correlation of error terms between observations, in all tested models error terms are clustered at the regional level. Apart from implementing standard tests for coefficient statistical significance, I also report coefficients that remain significant after the Bonferroni correction for multiple outcome comparisons.

The main coefficient of interest \(\beta\) stands for the impact of MC eligibility on analysed outcome variables. A considerable advantage of regression discontinuity specifications lies in the fact that this design makes use of theoretically near-complete randomisation at the immediate neighbourhood of the intervention cut-off threshold, thus providing unbiased estimates of local average treatment effects (LATE). However, it is worth noting that the validity of RDD models critically depends on the correctness of functional form assumptions. This consideration leads me to test for each analysed outcome different sets of models that vary in terms of the functional form of the trend (ranging from linear and to 3rd degree of polynomial), the birth timeline window around the cut-off period of January 2007 (models with 36-, 24-, 12-month windows), as well as the inclusion of other covariates. In addition, to allow for more functional flexibility, nonparametric local polynomial regressions (Lowess) are tested as robustness checks and their results are provided in Appendix 3.1.

4.1 Child Health Outcomes

First, I evaluate the MC impact on a range of reported child health outcomes. There are several channels through which MC may have affected child health. For example, better housing conditions are known to be associated with lower rates of infections (Ali et al., 2018), and better general physical and mental health (Pevalin et al., 2017; Rolfe et al., 2020).

During the RLMS interview, the most straightforward health measure is provided by parents when they are asked to assess the state of health for each of their children on a scale from 1 (excellent) to 5 (bad). Children who received scores 1 and 2 were deemed to have good/excellent health. These measures are subjective and are likely to be affected by a host of factors, such as parental education, social background, and, generally, parents’ perception of what stands for good and bad health. To partially overcome this issue, these variables are complemented with more objective health metrics that include the number of reported child chronic conditions and the occurrence of a health problem in the last 30 days.

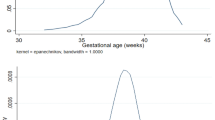

Estimation results are presented in Tables 3 and 20 in Appendix 3 and are illustrated by nonparametric Lowess regression fit shown in Figure 1 in Appendix 3. The results suggest that children living in MC-eligible households may have experienced a small overall improvement in general health. Although the coefficients tend to take the sign that is indicative of a positive change, only coefficients for the number of chronic are statistically significant in certain specifications. The MC eligibility is estimated to have reduced the number of reported child chronic conditions by 0.1-0.35. The additional analysis reported in Tables 25, 26, 27 in Appendix 3 suggests that the effect might be driven by rural households who likely invested the MC subsidy into providing central heating in their housing, and from female children. However, due to small sample sizes, heterogeneity analysis estimates tend to be highly volatile. Thus, they should be interpreted as tentative. Additional heterogeneity analysis by the poverty status is provided and by child gender later in this section.

4.2 Child’s Patterns of Time Spending

In this subsection, I evaluate the impact of the MC reform on the formation of human capital and developmentally relevant activities of children. One eligible MC use is funding or co-funding educational and childcare expenses for the child (e.g. private educational classes and programs, private childcare) after they turn three years old. Thus, it may contribute to the child’s human capital formation by providing enriched learning/living environments.

I analyse variables reflecting the amount of time children spend on different out-of-school activities, measured in minutes per week. These activities reflect parental investment in child human capital through providing opportunities for extracurricular activities, most often in the form of private tutoring for a foreign language, other school subjects, extracurricular arts (including evening art school, dance classes) and extracurricular sports activities. The variable total productive time sums all time spent by children on these activities. In addition, I include a variable on the parent-reported amount of time a child spends watching TV/using a computer for non-educational purposes. This outcome serves as a proxy for the time devoted to unproductive leisure activities that generally do not significantly contribute to the formation of the child’s human capital.

Estimation results for RDD models with varying sets of covariates and window widths are provided in Table 3 and are visually illustrated by nonparametric Lowess regression fit in Figure 2 in Appendix 3. Overall, outcomes show statistically insignificant results. However, with regard to extracurricular studies and arts, relatively stable coefficient signs and magnitudes across specifications indicate that small shifts may have occurred in these two variables (10–15 and 40–80 min per week increase, respectively).

4.3 Child Well-Being Outcomes

The third set of child outcomes analysed in this section addresses the child’s well-being and parental effort to ensure a sufficient level of child’s material and emotional comfort. To measure factors that are known to influence the level of children’s life satisfaction, I included in the set of studied outcomes: the reported number of attended cultural events/trips (e.g. exhibitions, museums, galleries, cinema theatres) in the past 12 months; an indicator variable for the child seeing their friends regularly at least three times a week; an indicator variable that at least one parent spent the child’s school vacation with the child, and the reported use of a personal computer (for any purposes). In addition, since MC could be spent on private childcare services after the child turns three years old, I included indicator variables for receiving any childcare within the last seven days from any individual who does not belong to the household and a similar indicator for receiving childcare from a family member who does not live in the same household. Finally, due to the presumed significant interdependence between the child’s and the mother’s well-being, I included the reported subjective measure of the mother’s life satisfaction as an outcome variable.

RDD estimates of the MC eligibility effect on the described well-being outcomes are provided in Table 3. Findings suggest that MC may have adversely affected child socialisation by reducing the number of children with frequent contact with friends by 20-30 p.p. The hypothesised channel is that MC allowed certain families to move to other residential locations, which may have impacted the robustness of the child’s social networks. The heterogeneity analysis presented in this Sect. 5 and Appendix 3 suggests that male children and those who lived in an urban environment at the moment of the RLMS interview, as well as wealthier households, were affected more strongly by this effect.

Table 3 also provides evidence that the frequency of attending cultural events may have decreased by around 3–3.5 events per year in MC-eligible households. Heterogeneity analysis in Appendix 3 points to the possibility that this effect may be primarily driven by children living in urban settings and poorer households, and who also tend to be female.

Finally, in some specifications, MC shows a positive effect on mothers’ subjective life satisfaction (around 0.3–0.6 points in models that yield statistically significant estimates). In Table 28 of Appendix 3, this effect appears more accentuated in households living in wealthier families, who, other things equal, may also have had more available options to benefit from the MC program.

4.4 Household-Level Outcomes

The last set of analysed outcomes concentrates on household-level outcomes, including general spending patterns, household diets, household financial behaviour, and housing conditions.

First, the MC eligibility may have affected the dynamics of household financial decisions. Since the MC could and was frequently used as a mortgage downpayment, it can be expected that a certain percentage of MC-eligible households started accumulating savings to afford a mortgage or even make a direct real estate purchase/exchange. However, after the bank loan/mortgage was taken, households may have had different financial goals and constraints. To meet financial obligations to respective banking institutions, these households would be more likely to resort to borrowing money from private individuals (e.g. family, friends) and, on the other hand, would be less likely to either lend money themselves or hold significant savings before the loan/mortgage is paid off. An outstanding loan/mortgage is also expected to affect household consumption and spending. For example, a higher bank debt burden may push the household toward making more economical decisions. In terms of spending and diets, it may translate into higher consumption of basic and less expensive food items, lower expenses on clothing, and lower non-essential expenditures.

It is known that nutrition has a profound effect on human health. The current evidence base shows that nutritional deficiencies in early childhood are associated with a range of negative consequences, including lower child IQ (Nyaradi et al., 2014), increased somatic morbidity (Uauy et al., 2008), and a higher risk of developing mental health disorders in adulthood (Muscaritoli, 2021). Although dietary guidelines are particularly notorious for being prone to change, there is a general consensus that consumption of certain nutrition groups (notably, vegetables and fruit) is associated with better health outcomes. In contrast, prolonged and excessive consumption of certain other nutrition groups, such as refined sugar, high-sugar treats, and processed foods, leads to an increased long-term risk of morbidity and illness.

The RLMS survey provides extraordinarily detailed information on self-reported household consumption of foods and food categories. I aggregated these variables into eight major consumption groups: vegetables/legumes (both fresh and canned), fruit (both fresh and canned), meat and poultry, dairy (including milk, butter, and cheese), refined sugar, high-sugar treats (tarts, candies, caramels, chocolate), starches (i.e. high-glycaemic crops and foods, such as bread, potatoes, pasta, buckwheat). The last included group—consumption of high-alcohol beverages (e.g. vodka, rum)—was assumed to be destined only for adult consumption and reflects the expenses made by heads of the household for their recreation or sustaining their habits.

Outcomes reflecting household general spending behaviour can be broadly divided into essential goods (essential food items, clothes, essential services, fuel, and utilities), non-essential (luxury) expenditures, and financial outcomes (household savings and reported loan payments). These measures reflect monthly reported household spending (inflation-adjusted, in 2011 prices) on each of these categories. In addition, I include an indicator variable for purchasing a durable good by surveyed adult household members within three months prior to their RLMS interview. It is worth noting that while RLMS provided information on the total household consumption, no data is available on how much was consumed by the child individually. Thus, this analysis relies on the assumption that household spending and dietary habits have a spillover effect on children, although the precise magnitude of such influence is difficult to evaluate for each participating family. A more detailed description of these and other variables is provided in Appendix 1.

Finally, I also analyse a set of variables reflecting household housing conditions. The MC subsidy may have significantly facilitated housing repairs or the provision of basic conveniences, such as centralised hot water supply, heating, and sewerage. It is expected that MC-eligible households needing such services were more likely to afford them with the financial support provided through the MC subsidy.

The RDD estimates of MC impact on household dietary and spending outcomes are presented in Table 4. Overall, the results indicate no robustly statistically significant differences between MC-eligible and MC-ineligible families for most outcomes. However, although statistically insignificant, models for certain food categories yield consistently stable \(\beta\) values. In particular, MC-eligible households tend to report a lower vegetable consumption and a higher consumption of refined sugar and sugar treats, which is consistent with a lower quality diet.

As for spending categories, MC-eligible households, in general, report lower spending on clothing (1.3-2K Rub/40-65 USD reduction) and potentially higher spending on essential food items (by 1-3K Rub/30-100 USD), which is more consistent with the hypothesis of a sparing consumption profile observed under the circumstances of an outstanding financial obligation.

Table 4 reports the MC eligibility effect on household financial outcomes and housing conditions. Consistent with the active loan hypothesis, on average MC-eligible households report higher bank loan payments and a higher probability of borrowing money from a private individual in the past 12 months. Results for household loan payments expressed as a share in the total household income are reported in Table 23 in Appendix 3 and provide similar findings. Although statistically insignificant, models also produce stable \(\beta\) coefficients pointing to a lower probability of high-volume savings and a lower likelihood of lending money to private individuals in MC-eligible families.

As far as housing conditions are concerned, evidence suggests that at least some households used their MC subsidy toward improving housing conditions by ensuring access to central heating and sewerage in their housing. Of note, some coefficients (i.e. borrowing from a private individual and the presence of central sewerage in the house in select models) stand the test of 5% statistical significance even after the Bonferroni correction for multiple outcome testing.

5 Heterogeneity Analysis

5.1 By Child Gender

The MC subsidy could have a differential effect on sub-populations. The fact that the MC subsidy could be spent on improving housing conditions makes this reform similar to the widely known family relocation program called Moving to Opportunity (MTO) which was implemented in several major US cities. Two influential studies on the effect of MTO by Kling et al. (2005, 2007) found that housing vouchers allowing participating families to relocate to less poverty-affected areas had a differential impact on children participating in the experiment. In particular, the authors concluded that young females benefited substantially from MTO participation in terms of their mental health, education, and engagement in risky activities. However, these positive effects on girls were offset by a nearly identical adverse MTO impact on boys.

In this subsection, I investigate whether MC eligibility affected boys and girls differently with respect to their health, development, and well-being outcomes. Table 5 and Appendix 3 of this paper provide a summary of estimation results.

Overall, boys and girls appear to have reacted differently to the MC program eligibility in several outcomes. In line with Kling et al. (2005, 2007), I find that girls may have experienced an improvement in their health status. In particular, girls saw an average 0.14–0.24 improvement in their health score and a 0.16–0.48 reduction in the reported number of chronic health conditions. Tests on the equality of \(\beta\) coefficients provided in the last column of Table 5 reveal that these differences between girls and boys are statistically significant at 5% level. Surprisingly, girls in MC-eligible families were reported to go to fewer cultural events while spending significantly more time on extracurricular arts (an additional 1–4 hours per week).

While both boys and girls may have experienced a decline in the number of social contacts with their peers, heterogeneity analysis suggests that boys were more strongly affected by it. I hypothesise that a certain proportion of households used the MC as a mortgage downpayment and moved to a new residential address. It appears that boys had a harder time finding new peer networks and substituted previous peer relationships with stronger familial connections and formal childcare. This may be reflected by a significant increase in the share of MC-eligible families where children spent their vacation with parents and a 15-30 point increase in the percentage of children who reportedly received any childcare in the past seven days. Conversely, the need to provide external childcare, both formal and through another family member, appears to have decreased for girls by 10–20 percentage points.

5.2 By Rural/Urban Areas

The nature of the MC subsidy makes it likely that different Russian regions were impacted differentially by this reform. Insofar as the size of the MC certificate—around 10,000 USD in 2007 prices—was not adjusted for local price levels, this subsidy had vastly different purchasing powers across Russia (see Sect. 2 for more context). In particular, concerning fertility effects of the MC, this point was addressed by Sorvachev and Yakovlev (2020), who showed a more sizable impact of the MC in regions with a higher ratio of subsidy size to regional housing prices. While a limited number of observations the RMLS data does not allow me to carry out the analysis at the regional level, I approximate the difference between low- and high-cost areas by examining Russian rural and urban areas. Results for main parametric RDD models (12- and 36-month time window) are summarised in Table 6, and complementary estimates are presented in Tables 25, 26, and 27 in Appendix 3.

Heterogeneity analysis suggests that rural and urban households reacted differently to MC eligibility across several dimensions. Estimation results indicate reduced consumption amounts of meat and poultry (by around 2.5kg), fruit (by 2–4 kg), and possibly vegetables, reported by rural MC-eligible families. However, since analysed consumption volumes only reflect purchased amounts of these food categories, part of this decrease may be accounted for by subsistence farming in rural areas.

As for household financial behaviour, although MC-eligible rural households did not report increased bank loan payments, they were significantly more likely to borrow from private individuals and had a much lower likelihood of holding significant savings or lending money. This behaviour is consistent with using the MC subsidy to improve housing conditions by conducting housing repairs without resorting to significant bank loans. As for child outcomes, estimation results in Tables 6 and 25 in Appendix 3 suggest that observed health improvements are also driven primarily by rural households. Altogether, obtained estimates point to the possibility that improved access to basic conveniences (e.g. central heating and sewerage) may have played a positive role in preventing child morbidity. Of note, the descriptive statistics in Table 14 in Appendix 2 show a stark difference between rural and urban Russian households regarding access to basic conveniences and essential public utilities. Only about 20% of rural Russian households reported having access to hot water supply, central heating, and sewerage in their housing, compared to 80–90% of families living in urban areas.

As for urban MC-eligible households, RDD estimation results indicate a higher bank loan burden compared to MC-ineligible households, both in absolute terms and as a share of expenses in the total household income (see Tables 26 in Appendix 3). These families also tend to report higher spending shares on essential food items, basic expenditure, and utilities, as well as lower spending on clothes. In addition, MC-eligible urban households and a higher propensity to resort to borrowing from private individuals. This behaviour is consistent with a more sparing consumption type characteristic of a household having a significant outstanding financial liability, such as a mortgage.

5.3 By Poverty Status

Households with different levels of material wealth can be expected to react differently to MC incentives. The fact that in most cases the MC subsidy size was insufficient to purchase real estate directly can render the benefits of the MC reform partly inaccessible to poorer households that cannot afford a mortgage and do not have enough savings to purchase real estate immediately. This possibility is studied in the present subsection, wherein the poverty status is self-reported by RLMS survey respondents, who were asked whether they experienced difficulty providing themselves with essential consumer goods in the last 12 months (see Appendix 1 for more details on the RMLS questionnaire). Results of the RDD model estimation are summarised in Tables 6 and 28, 29, and 30, in Appendix 3.

RDD estimates provide tentative evidence that poorer MC-eligible households made some adjustments to their diets. In particular, these households tended to report higher consumption of dairy (by 2–3 litres) and strong alcoholic beverages (by around 0.15 litres). Although generally statistically insignificant, estimated coefficients for wealthier households tended to be of the opposite sign.

As far as housing conditions are concerned, poorer MC-eligible families had a higher likelihood of living in dwellings equipped with central sewerage and central heating, which appears to be the result of investing the MC subsidy in improving housing conditions. Of note, poorer households were also more likely to borrow from private individuals than from banking institutions.

Children in poorer MC-eligible families also, on average, report more time spent watching TV/browsing the Internet for non-educational purposes than their MC-ineligible counterparts (by 40-100 mins per week). Wealthier MC-eligible households, on average, reported more problems with child socialisation proxied by seeing friends more than two times per week. I hypothesize that these problems may result from adaptation difficulties encountered by children whose families could have moved to a new residential address. Consistent with earlier estimation, wealthier MC-eligible households also report higher bank loan monthly payments (both absolute and expressed as a share of total household income) and higher rates of borrowing from private individuals than similar MC-ineligible families.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

This study evaluates the impact of the Maternity Capital (MC) child subsidy of 250.000 Rub (7.150 euros or 10.000 USD, in 2007 prices) that was introduced on 1 January 2007. To be eligible, a woman had to give birth to/adopt a second or a subsequent child. The MC could be spent in a limited number of ways, namely to improve family housing conditions, sponsor children’s education/childcare, or invest it in the mother’s retirement fund.

Using RLMS individual and household representative panel surveys from 2010 to 2017, I test regression discontinuity models whose aggregate level estimates point to the possibility that children in MC-eligible households had a moderately lower incidence of chronic health conditions (by around 0.15, or more than 40 % compared to MC-ineligible families) and a lower percentage of children who were reported to see their friends at least three times a week (i.e. a more than 30 % decrease relative to MC-ineligible families). Additional effect heterogeneity analysis suggests that the estimated improvements in the health status may be driven primarily by female children and poorer, rural MC-eligible households who were more likely to report that their housing had basic conveniences and public utilities (e.g. central heating and sewerage). At the same time, the reduction in child socialisation was more pronounced in male children, as well as in MC-eligible urban and wealthier families whose consumption and spending profiles are more consistent with having a significant outstanding financial obligation (e.g. a mortgage).

As for the heterogeneity of the MC eligibility impact across different sociodemographic groups, the most important and visible distinctions tended to arise when comparing rural/urban and poor/wealthier households. In particular, MC-eligible rural households were significantly less likely than MC-ineligible families to report a high level of savings or resort to consumer loans. Instead, to obtain external funding, these families tended to turn to borrowing from private individuals. In the meantime, compared to MC-eligible rural households, MC-eligible families living in urban areas were more likely to have higher loan liabilities and higher savings. Such behaviour is suggestive of different financial goals and liabilities across these subpopulations: rural and poorer households exhibited behaviour that is consistent with a one-time financial investment (e.g. improving housing conditions by equipping the house with central heating and sewerage), while the behaviour of urban and wealthier households was more consistent with using the MC subsidy to take out a mortgage or save up for a downpayment.

Overall, MC-eligible families also tended to report higher volumes of monthly bank loan payments, a higher likelihood of borrowing money from private individuals, and a lower probability of acting as a lender. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that a significant percentage of MC-eligible households used their subsidy to improve housing conditions.

However, due to small sample sizes, the estimates obtained in the effect heterogeneity analysis are generally volatile with respect to functional form specifications, the choice of window width around the intervention cut-off date, and the inclusion of additional covariates. 5Thus, evidence from the heterogeneity analysis should be interpreted as tentative.

Another limitation of the empirical strategy consists in the possibility of mothers’ self-selection into the MC eligibility in specifications using wide time windows around the MC eligibility cut-off date. In particular, RDD models for covariates reported in Appendix 5 point to the possibility that self-selection might have occurred in specifications with a 24- and 36-month bandwidth based on income and the self-identified poverty status. To address these insignificantly concerns, when interpreting RDD estimation results, the specifications using a 12-month bandwidth were considered as the main ones, even despite a potentially lower efficiency of derived estimates and a lower statistical power of the associated t-tests due to restricted sample sizes.

Since RLMS data are of survey type where respondents tend to provide their subjective evaluations, these data are likely by various factors related to respondents’ personality traits, past experiences, and unobserved socio-economic characteristics. While not affecting the unbiasedness of RDD estimates, it likely brings additional noise to both outcome and covariate variables. This results in a decreased efficiency of obtained estimates.

The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it concentrates on a middle-income transitioning country, for which little evidence regarding pro-natalist policies is currently available. Second, it features a number of outcomes reflecting child well-being and human capital formation that, to the best of my knowledge, no other study had attempted to investigate, including patterns of time spent by children. Lastly, the RLMS survey allowed me to incorporate household-level outcome variables that no other study had attempted to evaluate systematically, including patterns of household lending, borrowing, and housing quality.

Child and household outcomes analysed in his paper were likely to be affected by the MC eligibility through several channels. First, since the MC is known to be frequently used as a mortgage downpayment, the financial behaviour of some households is expected to be affected by an ongoing financial liability. For example, to meet financial obligations to respective banking institutions, these households could be more likely to resort to borrowing money from private individuals (e.g. family and friends) and, on the other hand, would be less likely to either lend money themselves. This channel plausibly affected urban MC-eligible populations more strongly with regard to their borrowing behaviour, inasmuch as they reported a higher level of credit liabilities and a higher propensity to take out loans both from financial institutions and from private lenders. In addition, an outstanding loan, mortgage, or a significant prospective investment are expected to push households—at least temporarily— toward making more economical decisions. In terms of household spending and diets, it may translate into higher consumption of basic and less expensive food items, lower expenses on clothing, and potentially lower general and non-essential expenditures. The estimation results provide tentative evidence of a more austere consumption profile observed in rural families whose spending likely diminished after becoming eligible for the MC, as evidenced by consistently negative, albeit generally insignificant, coefficients across most consumption groups.

Second, in purely financial terms, the MC provides a very sizable income supplement that can relax, at least in the short term, the household budget constraint in MC-eligible families. As a result, the affected families may respond to MC incentives by re-calibrating their household spending behaviour. In particular, MC eligibility could affect households’ spending decisions regarding the share of the resources to be invested in children’s human capital (e.g. child education and childcare) vs. family members’ short-term (e.g. current consumption) and long-term needs (e.g. investing in better housing conditions). As far as investment in child human capital is concerned, there is tentative evidence that wealthier families benefitted the most from the MC, insofar as they reported better children’s involvement in extracurricular arts and a longer time spent on scholarly activities at home.

Lastly, the MC reform was plausibly accompanied by a broader shift in social policy priorities. The Russian state stood behind some public campaigning aimed at encouraging child adoptions, as well as preventing alcoholism, household abuse, and other forms of deviant behaviour that are not uncommon in Russian families. In particular, the World Health Organization (2014) survey on the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences among young (aged 16–25) people in the Russian Federation estimated that the prevalence of physical abuse stood at 14%, emotional abuse—at 37.9%, physical neglect—at 53.3%, and emotional neglect—at 57.9%. A total of 17.5% respondents reported experiencing four or more adverse childhood events, which is significantly higher than figures reported in similar surveys conducted in Europe. It is plausible that improved housing conditions and better access to child care may have in part mitigated these societal issues, although the extent to which this channel affected child outcomes across different family demographics is challenging to evaluate.

The results of this study could be generalised to institutionally, demographically, and economically close countries, most notably Belarus. Arguably to a lesser extent, these conclusions can be used for policy recommendations in other largely similar countries, which, however, differed from Russia in terms of the type of state institutions (e.g. Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria), prevalent societal norms with regard to family and religion (for instance, predominantly Muslim but economically similar Kazakhstan, Turkey, and Malaysia).

This study can be complemented in a number of ways. For example, additional outcomes related to family relationships can be investigated in more depth. Since the MC certificates are tied to mothers, this subsidy can provide a higher degree of their financial independence. Thus, MC stimuli can potentially affect such outcomes as the probability of divorce, spending on personal items, and the patterns of time spent by mothers and other household members.

Data Availability

Data used in this study are publicly available and can be downloaded from https://www.hse.ru/en/rlms/downloads. The code used in this study is re-deposited at https://github.com/alexproshin/RLMS.

Notes

Urban is defined as living in a city or in a regional centre, in accordance with the RLMS statistical classification

References

Ali, S. H., Foster, T., & Hall, N. L. (2018). The relationship between infectious diseases and housing maintenance in indigenous Australian households. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 2827.

Baughman, R., & Duchovny, N. (2016). State earned income tax credits and the production of child health: Insurance coverage, utilization, and health status. National Tax Journal, 69(1), 1030–132.

Case, A., Lubotsky, D., & Paxson, C. (2002). Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1308–1334.

CIAN. (2020). How did apartment prices evolve in Moscow? (in Russian, page last cosulted on September 16, 2020) https://www.cian.ru/stati-kak-izmenilis-tseny-na-kvartiry-v-moskve-218051/

Currie, J. (2009). Healthy, wealthy, and wise: Socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 87–122.

Dahl, G., & Lochner, L. (2012). The impact of family income on child achievement: Evidence from the earned income tax credit. The American Economic Review, 102(5), 1927–1956.

Demoscope. (2019). Fertility, mortality and natural population growth in Russia in 2006-2019, by month. (page last modified in 2019). http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_month.php

Deutscher, N., & Breunig, R. (2018). Baby bonuses: Natural experiments in cash transfers, birth timing and child outcomes. Economic Record, 94(304), 1–24.

Gaitz, J., & Schurer, S. (2017). Bonus skills: Examining the effect of an unconditional cash transfer on child human capital formation. IZA Discussion papers.

Kling, J., Liebman, J., & Katz, L. (2007). Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica, 75(1), 83–119.

Kling, J., Ludwig, J., & Katz, L. (2005). Neighborhood effects on crime for female and male youth: Evidence from a randomised housing voucher experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(1), 87–130.

Lee, D., & Lemieux, T. (2010). Regression discontinuity designs in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 48, 281–355.

Levada Center. Trust in public institutions (Survey), (2014). https://www.levada.ru/2014/11/13/doverie-institutam-vlasti-3/ (in Russian)

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., et al. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239.

Muscaritoli, M. (2021). The impact of nutrients on mental health and well-being: insights from the literature. Frontiers in Nutrition

Nyaradi, A., Li, J., Hickling, S., Foster, J., & Oddy, W. (2013). The role of nutrition in children’s neurocognitive development, from pregnancy through childhood. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 97.

Pevalin, D., Reeves, A., Baker, E., & Bentley, R. (2017). The impact of persistent poor housing conditions on mental health: A longitudinal population-based study. Preventive Medicine, 105, 304–310.

Rolfe, S., Garnham, L., Godwin, J., et al. (2020). Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: Developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health, 20, 1138.

Rosstat. Consumption and income statistics of Russian households: How do we assess changes? (in Russian) (2020). https://rosstat.gov.ru/free_doc/new_site/rosstat/smi/konferenz/ovcharova_prez.pdf

Slonimczyk, F., & Yurko, A. (2014). Assessing the impact of the maternity capital policy in Russia. Labour Economics, 30, 265–281.

Sorvachev, I. & Yakovlev, E. (2020). Could a child subsidy increase long-run fertility and stability of families? Could it have equilibrium effects? Evidence from the maternity capital program in Russia. SSRN Working Papers.

Uauy, R., Kain, J., Mericq, V., Rojas, J., & Corvalán, C. (2008). Nutrition, child growth, and chronic disease prevention. Annals of Medicine, 40(1), 11–20.

World Health Organization. (2014). Survey on the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences among young people in the Russian Federation (Report).

Acknowledgements

I thank Helene Huber, Mark Stabile, Randall Ellis, Lise Rochaix, Audrey Laporte, and the Hospinnomics team for their useful and valuable comments that helped improve this manuscript

Funding

The author did not receive financial support from any organization for the submitted work. The author has no financial interests or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author reports no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. RLMS Questionnaire

See Table 7.

Appendix 2. Descriptive Statistics

See Tables 8

, 9

, 10

, 11

, 12

, 13

, 14

, 15

, 16

, 17

and 18.

Appendix 3

1.1 Lowess Specifications

As mentioned in Sect. 4, although RDD models can produce unbiased treatment effect estimates due to near-complete randomisation around the cut-off threshold, this property depends on the correctness of the functional form of the trend before and after the intervention. While polynomials specifications with to the 3rd degree and a jump at the cut-off value are a very widespread approximation used in applied research, it is generally recommended to apply semi- and non-parametric methods to provide additional evidence supporting the robustness of obtained results.

It is worthwhile to note that the functional flexibility of Lowess comes at a cost. In the context of this study, the most important disadvantage lies in the lack of robust methods for deriving errors and confidence intervals. Neither window overlap (used in this study) nor bootstrap—the two popular derivation methods – can produce consistent standard errors without making restrictive model assumptions. Secondly, these methods cannot completely overcome the issue of choosing a functional form since point estimates in non-parametric models (such as Lowess and kernel regression) also rely on implicit assumptions relating, for example, to the degree of curve smoothing. Finally, this moderate advantage of increased flexibility also comes at the cost of having to deal with the curse of dimensionality. It manifests itself in a process whereby as the model complexity grows, for an increasingly high share of data/prediction points it becomes impossible to find sufficiently close matches among available observations for most kernel weighing functions. As a result, it severely restricts the number of covariates that can be included in models. Thus, it is generally recommended to view semi- and non-parametric estimation as a complement rather than a substitute for functional RDD. (Lee and Lemieux, 2010)

In this Appendix, I test local linear regression models (Lowess) of the form \(y_{i} = f(birthtimeline_{i} + post2007_{i}) + \epsilon _{i}\) wherein, as explanatory variables, I include the birth timeline centred at January 2007 and having the month as the measurement unit, and the dummy post2007 for births in or after January 2007. Observation weights, provided by a tricubic kernel function, are computed with and without taking post2007 variable into account (i.e. “2d kernel" and “1d kernel" fit).

Non-parametric Lowess estimation results for the MC eligibility effect on various child and household outcomes are presented in Table 19 in Appendix 3. Overall, although the results are vastly statistically insignificant, the effect signs and sizes mirror the main findings of the parametric RDD. In particular, Lowess estimates validate a 0.1-0.2 reduction in the number of reported child chronic health conditions, which might be linked to improved housing conditions (i.e. a higher estimated prevalence of housing units with central heating and central sewerage in MC-eligible families). On the other hand, Lowess models also confirm the moderately negative impact of MC on some socialisation metrics. Of particular concern is an estimated 20-25 p.p. reduction in the share of children who reportedly saw their friends more than two times per week. Social isolation and loneliness are known to be significant risk factors for developing depression and anxiety both during periods of reduced social contact and afterwards (Loades et al., 2020).

As far as household financial behaviour is concerned, Lowess models render similar estimation results with regard to the observed increase in the average volume of monthly loan payments (2-3.5K Rub/65-120 USD), a higher share of MC-eligible households who borrow from private individuals, a reduced share of lending households, as well as a lower share of households with significant savings.

Lowess estimation depicts a similar consumption profile of MC-eligible families. In particular, MC-eligible families are found to spend more resources on essential food items (1.2-3K Rub/40-100 USD), utilities (0.7-1.3K Rub/25-40 USD), and less on clothing (1-1.5K/30-50 USD). The estimates for non-essential items and household savings made in the last 30 days tend to be of unstable magnitude, however. Finally, consistently negative coefficients for the consumption of strong liquors in models with different time windows and specifications provide tentative evidence for a decreased consumption of strong liquors by around 0.1-0.2 litres per week

3.2 Additional Regression Tables

See Tables 20

, 21

, 22

, 23

, 24

, 25

,26

, 27

, 28

, 29

and 30.

See Figs. 1

, 2

and 3.

Appendix 4: Models for Covariates

See Tables 31

and 32.

See Figs. 4

and 5

.

Appendix 5: Models for Covariates, RDD Effects in August 2007

See Table 33.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Proshin, A. Impact of Child Subsidies on Child Health, Well-Being, and Investment in Child Human Capital: Evidence from Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey 2010–2017. Eur J Population 39, 14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-023-09653-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-023-09653-8