Abstract

In this paper, I aim to establish that, according to almost all democratic theories, instrumentalist considerations often dominate intrinsic proceduralist considerations in our decisions about whether to make extensive use of undemocratic procedures. The reason for this is that almost all democratic theorists, including philosophers commonly thought to be intrinsic proceduralists, accept ‘High Stakes Instrumentalism’ (HSI). According to HSI, we ought to use undemocratic procedures in order to prevent high stakes errors - very substantively bad or unjust outcomes. However, democratically produced severe substantive injustice is much more common than many proponents of HSI have realised. Proponents of HSI must accept that if undemocratic procedures are the only way to avoid these high stakes errors, then we ought to make extensive use of undemocratic procedures. Consequently, according to almost all democratic theorists, democratic theory ought, for practical purposes, to be reoriented towards difficult moral and empirical questions about the instrumental quality of procedures. Moreover, this is potentially very practically important because if there are available instrumentally superior undemocratic procedures, then wholesale institutional reform is required. This is one of the most potentially practically important findings of normative democratic theory. In spite of this, no-one has yet explicitly recognised it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this paper, I aim to establish that according to almost all democratic theories, instrumentalist considerations should in our world often dominate in our decisions about whether to use undemocratic procedures. The reason for this is that almost all democratic theorists, including philosophers commonly thought to be intrinsic proceduralists, accept ‘High Stakes Instrumentalism’ (HSI). According to HSI, we ought to use undemocratic procedures in order to prevent high stakes errors – very substantively bad or unjust outcomes. Since, so I shall argue, all democracies routinely produce high stakes errors across most areas of policy, proponents of HSI must accept that instrumentalist considerations dominate in our decisions about whether we ought to make extensive use of undemocratic procedures.

This has two important implications. Firstly, according to almost all democratic theorists, democratic theory must, for practical purposes, be significantly reoriented away from a focus on political equality for its own sake, and towards difficult moral and empirical questions about the instrumental quality of procedures. A natural impression one might get from contemporary democratic theory is that, for many philosophers, the possibility of feasible instrumentally superior undemocratic procedures is simply irrelevant to which political procedures we ought to use. For these philosophers, the justifiability of our use of democratic procedures is not contingent on such facts. In fact, this picture is mistaken. If I am right, then from the point of view of almost all democratic theorists, the possible existence of feasible instrumentally superior undemocratic institutions is relevant to which political procedures we ought to use. In this respect, the gap between pure instrumentalists and almost all other democratic theorists is much smaller than it might at first appear.

Secondly, if there are instrumentally superior undemocratic institutions, then HSI requires that we ought to make extensive use of them. If, for example, expert control of drug policy would prevent the currently occurring high stakes errors produced in all democracies, then almost all democratic theorists must accept that we are morally obligated to hand these decisions over to experts. This is one of the most potentially practically important findings of democratic theory, but, to my knowledge, no-one has yet explicitly acknowledged it.

It should be made clear that at no point in this paper do I try to defend HSI. My goal is rather to show that almost all leading democratic theorists accept HSI and in turn show the extent to which they have to engage with instrumentalist arguments for undemocratic institutions. Moreover, it seems as though HSI is a principle which any prima facie plausible democratic theory ought to accept. It appears to be very difficult to defend the view that majorities have the right to violate fundamental rights, or, in general, to be tyrannous to minorities. Thus, while denying HSI is an option, it is not a palatable one. Indeed, the fact that almost all democratic theorists accept HSI provides some indication of its intuitive strength.

The paper is structured as follows. In section 1, I define ‘democracy’, ‘instrumentalism’ and ‘intrinsic proceduralism’. In section 2, I show that nearly all democratic theorists, including philosophers commonly thought to be intrinsic proceduralists, are committed to High Stakes Instrumentalism. I argue that HSI, in conjunction with theses I call ‘Superiority of Undemocratic Procedures’ (SUP) (which I do not attempt to defend) implies that we ought to make extensive use of undemocratic procedures. In section 3, I defend a claim I call ‘Pervasive High Stakes Democratic Errors’ (PHSE) which says that all extant democratic states routinely produce high stakes errors in most areas of policy. If PHSE is true, then the case for one part of SUP appears very strong. The case for and against the second part of SUP is highly complex and must be discussed elsewhere.

1 Democracy, Instrumentalism and Intrinsic Proceduralism

I understand democracy to be broadly to do with popular sovereignty – rule by the people, meaning that each person must have an equal say over political decisions:

Democracy – A procedure is democratic if and only if it distributes (opportunities for) influence over political decisions equally among all members of the group.

This definition is meant to be ecumenical between different procedural understandings of democracy. It is, for example, consistent with a narrow aggregative understanding of democracy (one person, one vote, one weight) and a deliberative democratic conception: each theory can cash out what ‘opportunity’ means in accordance with their own theory.Footnote 1

On this definition, procedural features alone determine whether a procedure is democratic; procedures do not become democratic because they produce substantively just outcomes or because they produce decisions which protect democratic rights. Ronald Dworkin (2000, chap. 4) denies this. He has, for example, argued that judicial review is democratic because of the quality of the outcomes it produces. As a semantic matter, this seems wrong. Judicial review allows a small body of unelected judges to override the expressed wishes of the majority. So, when judicial review overrides the wishes of the majority, judicial review seems to be a paradigm case of an undemocratic procedure. This is true even if a democratic government institutes judicial review as a check on future democratic decisions. This would be the democratically-approved institution of an undemocratic procedure.Footnote 2 The above definition of ‘democracy’ fits best with my semantic intuitions and those of many others. That aside, my main focus here is normative rather than semantic. My goal is to shed light on the reasons which determine whether we ought to use democracy, as I have defined it.

The instrumental worth of a political procedure is determined by how well it does at causally producing substantively just or valuable outcomes. As I understand them, the terms ‘justice’ and ‘value’ are annexed to nonconsequentialist and consequentialist theories, respectively (Broome 1991). Consequentialists are concerned with value only, whether construed in hedonistic terms or according to some other conception of value. Nonconsequentialists are concerned with justice, and most plausible nonconsequentialist theories are also concerned with both justice and value. Justice can be understood broadly to be to do with people’s rights. If an act violates someone’s rights, then that act is unjust.

The substantive value or justice of an outcome is the justice of an outcome which is not derived from its procedural pedigree. An outcome is any causal product of a political procedure.

Substantive value or justice – The value or justice of an outcome which is not derived from the value or justice of a procedure which may have produced the outcome.

All moral theories accept that certain outcomes are substantively bad or unjust. For example, genocide is substantively unjust because it is unjust regardless of the political decision-procedure which might produce it. Theories of substantive justice diverge on many other issues. According to libertarians, it is substantively unjust for the state to forcibly confiscate someone’s property without their consent. According to Rawlsians, it is unjust for the basic structure of society to fail to ensure that the least well-off group is as well-off as possible in terms of primary goods. These are propositions about the justice of actions, regardless of their procedural pedigree. So, they are propositions about substantive justice.

Some outcomes are valuable or just by virtue of their procedural pedigree. Call this the ‘retrospective value or justice’ of an outcome:

Retrospective value or justice – The value or justice of an outcome which is derived from the justice of the procedure which produced it (Estlund 2008, chap. 4).

For example, the outcome of a fair gamble is just by virtue of its procedural pedigree. If I bet £10 on a coin toss and I win, then I should get £10. But whether I should get £10 depends on the outcome of the coin toss. It is not true that I should get £10 if I call ‘heads’, and the coin comes up tails. The justice of this outcome depends on its procedural pedigree.

Procedures can be recommended on the basis of how good they are at realising substantively valuable or just outcomes. This is the instrumental worth of a procedure:

Instrumental procedural value or justice – A procedure is instrumentally valuable or just to the extent that it produces substantively valuable or just outcomes.

Any procedure, no matter how politically inegalitarian, could be instrumentally valuable or just. Many countries use politically inegalitarian procedures such as judicial review in order to produce superior outcomes.

Intrinsic procedural value or justice is the value or justice a procedure has by virtue of its intrinsic properties. Most intrinsic proceduralists work in nonconsequentialist theory and defend the intrinsic procedural justice of democracy. Propositions about intrinsic procedural justice can be expressed in terms of rights. If democracy is intrinsically just, then people have equal non-derivative rights to influence over political decisions. These rights are non-derivative because they are not justified by the substantive quality of their contingent causal consequences. For instance, according to intrinsic proceduralists, disenfranchising women is unjust regardless of whether it will cause their interests not to be taken account of in political decisions. The denial of political influence itself constitutes an intrinsic procedural injustice independent of what substantive injustice the procedural outcome might produce. We have duties owed to each person and correlative to their right to political influence, not to deny them political influence, regardless of what they will do with that influence.

2 High Stakes Instrumentalism

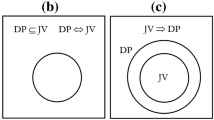

Pure intrinsic proceduralism is unpopular in contemporary political philosophy.Footnote 3 Democratic theorists are chiefly divided into two camps: pure instrumentalism (van Parijs 1996; Raz 1998; Dworkin 2000, chap. 4; Arneson 2004; Wall 2007; Estlund 2008; Brennan 2011), and hybrids of instrumentalism and intrinsic proceduralism. Two hybrid theories have been defended in the literature. According to the weaker version, we ought, for intrinsic proceduralist reasons, to use democracy as long as it does not produce substantive injustice, whether mild or severe (Ackerman 1980, chap. 9; Barry 1995, 108–112; Saunders 2010). If we could use elite rule in order to prevent substantive injustice, we ought all-things-considered to do so.Footnote 4

According to the stronger hybrid, we ought, for intrinsic proceduralist reasons, to use democracy as long as it does not produce severe substantive injustice. If we could use elite rule to prevent severe substantive injustice, we ought all-things-considered to do so. Nonetheless, we ought to accept mild substantive injustice for the sake of the intrinsic procedural value or justice of democracy.

Many democratic theorists endorse the stronger hybrid (Brighouse 1996; Gaus 1996, pt. 3; Buchanan 2002; Richardson 2002, pt. 1; Griffin 2003; May 2009; Valentini 2013). For example, Tom Christiano argues:

“[Democratic] institutions are partly evaluated by whether they manage to protect democracy, liberal rights, and the economic minimum. But beyond these there is no agreement on justice in law and policy in terms of which we can evaluate democracy from the egalitarian standpoint. Therefore, with the exception of these, democracy will be entirely intrinsically justified from the egalitarian standpoint.” (Christiano 2008, 73)

For Christiano, we have intrinsic proceduralist reasons to use democracy to decide on non-fundamental matters, such as distributive justice provided everyone is above the level of sufficiency (Christiano 2008, 97). However, we are permitted to use undemocratic institutions to protect ‘equally or more fundamental rights’, including liberal rights and the right to an economic minimum (Christiano 2008, 98). Christiano accepts that his theory ‘grounds only a limited scope for democracy’ (Christiano 2008, 97). He accepts that we ought, for instrumentalist reasons, to use undemocratic procedures in order to prevent severe substantive injustice.

Similarly, Joshua Cohen argues,

“Decisions should also be substantively just, according to some reasonable conception of justice, and effective at advancing the general welfare. But a principle of political equality states norms that will normally override other considerations, apart from the most fundamental requirements of justice.” (Cohen 2009, 271–272)

For Cohen, within certain limits – ‘the most fundamental requirements of justice’ – we have reason to use democracy regardless of the substantive quality of the outcomes it produces. Finally, according to Rawls, the basic liberties, including the political liberties, are lexically ordered above the second principle of justice, including the Difference Principle and fair equality of opportunity (Rawls 1996, 5–6). So, majorities have the right to produce mild substantive injustice by, say, violating the Difference Principle. However, majorities do not have democratic rights to violate more fundamental rights, such as the right to a social minimum providing for people’s basic needs (Rawls 1996, 228–229).

Although they differ on the details, all of these philosophers accept that instrumentalist reasons by themselves are sufficient to justify the use of undemocratic procedures in order to prevent democratically-produced severe substantive injustice. There are two possible ways to arrive at this conclusion. Firstly, it might be argued that instrumentalist reasons trump intrinsic proceduralist reasons when there is severe substantive injustice. The intrinsic proceduralist reasons entail that we have pro tanto reason to regret using undemocratic procedures, but given the strength of the instrumentalist reasons, we ought all-things-considered to use undemocratic procedures in order to prevent severe substantive injustice. Secondly, it might be argued that if democracy produces severe substantive injustice, there is nothing on the intrinsic proceduralist side of the scales. People do not have non-derivative democratic rights to cause severe substantive injustice. So, we do not even have pro tanto reason to regret using undemocratic procedures in order to prevent severe substantive injustice. Whichever of these theories is correct, the fundamental question I am interested in here is what kind of reasons determine the political procedures we ought all-things-considered to use. Both of these accounts say that instrumentalist reasons by themselves are sufficient to entail that we ought all-things-considered to use political procedures which do not produce severe substantive injustice.

Thus, both of the hybrid theories are committed to a form of High Stakes Instrumentalism:

High Stakes Instrumentalism (HSI) – For all cases in which we can feasibly use either a political procedure in the set of procedures S1, or a procedure in the set of procedures S2, and all procedures in the set S1 would actually produce high stakes errors if used, but those in S2 would not, we ought, for instrumentalist reasons, to use a procedure in S2 rather than S1.

For the purposes of this paper, high stakes errors are defined as severely substantively unjust outcomes (so these terms will be used interchangeably), rather than as very substantively bad outcomes.Footnote 5 The reason for this is that all proponents of hybrid theories believe that democratic rights are constrained only by the requirements of substantive justice – only by people’s substantive rights. However, this is just one form of HSI, and other forms focus on substantive value only. For example, utilitarianism entails a form of HSI according to which we ought to use undemocratic institutions if such procedures would prevent very substantively bad outcomes.Footnote 6 Since my main aim is only to show that the version of HSI endorsed by hybrid theorists is potentially very open to the use of undemocratic procedures, I will focus only on the justice-focused version in the remainder of the paper.

HSI implies that if, in some particular case, the only way to prevent democratically-produced severe substantive injustice is to use an undemocratic procedure, then we ought to do so. This is not to say that the fact that the procedures in S1 produces severe substantive injustice in one instance entails that we ought never to use a procedure in S1. Rather, the point is that if we could use a procedure in S2 in that instance – to make that particular political decision or set of political decisions – and thereby prevent the severe substantive injustice, then we ought to do so.

Note also that HSI implies that if the only way to prevent undemocratically-produced severe injustice is through the use of democratic procedures, then we ought to use democratic procedures. HSI says that we should choose the best means to avoiding high stakes errors, whatever those means are. It is an instrumentalist principle, not necessarily an undemocratic one.

HSI is neutral about whether it is true that intrinsic proceduralist reasons make a difference to the procedures we ought all-things-considered to use when we have to choose between procedures which do not produce high stakes errors. Therefore, HSI is compatible with it being true that if a democratic procedure D and an undemocratic procedure U would produce substantively perfect outcomes, then we ought, for intrinsic proceduralist reasons, to use D. HSI is also neutral on the following case. Suppose that in some policy area, a democratic procedure A produces severe substantive injustice, but that the democratic procedure B and the undemocratic procedure C do not. HSI only tells us that we ought not to use A and ought to use either B or C; it is neutral on which of B or C we ought to use. Therefore, it is compatible with the proposition that we ought, for intrinsic proceduralist reasons, to use B rather than C. Nonetheless, HSI still implies that if we can only avert severe substantive injustice by using an undemocratic procedure, then we ought to do so.

With this clarified, consider the following premise:

Superiority of Undemocratic Procedures (SUP) – For all extant democratic states and for most areas of policy, there exists a set of procedures, SU, that would not actually, if used, produce high stakes errors, and all procedures in SU are undemocratic.

HSI and SUP entail the following conclusion:

C. All extant democratic states ought to use undemocratic procedures in most areas of policy.

I do not attempt to fully defend SUP here, and I am personally unsure whether it is true. However, I will defend the truth of a thesis I call ‘Pervasive High Stakes Democratic Errors’ (PHSE), which says that all extant democratic states routinely produce high stakes errors on a massive scale in most areas of policy. These high stakes errors are very plausibly directly attributable to mistaken popular sentiment on the policies in question. Therefore, it is unlikely that alternative available democratic procedures would avoid these high stakes errors. In order to fully defend SUP, one would also need to defend the distinct proposition that available undemocratic procedures would prevent these high stakes errors. I make no attempt to defend this proposition, but it is not obviously false and so needs to be given careful consideration.

The preceding discussion has two important implications. Firstly, democratic theory ought, for practical purposes, to be significantly reoriented away from endorsing political equality for its own sake, and towards difficult empirical and moral questions about the instrumental quality of procedures. Hybrid theorists thus far appear to have assumed that HSI is a proviso which would require the use of undemocratic procedures only in very rare and extreme conditions. Consequently, they have proceeded as though we should be chiefly focused on improving procedures according to intrinsic proceduralist standards. This is a mistake. Intrinsic proceduralist considerations will often be dominated by instrumentalist considerations when we are deciding whether to make extensive use of undemocratic procedures. With respect to the practical question of whether we ought to make extensive use of undemocratic institutions, the difference between pure instrumentalists and almost all other democratic theorists is small.

Secondly, this is potentially hugely practically important, for if the second part of SUP is true, then there ought to be extensive institutional reform in most modern democracies.

An examination of the leading recent argument for restricted suffrage indicates how radical a change this would be for democratic theory, and in turn how potentially practically important this could be for our institutions. In ‘The Right to a Competent Electorate’ Jason Brennan argues that because many or most government decisions have high stakes, incompetent voters ought to be disenfranchised today and across the world (Brennan 2011). Proponents of HSI, i.e. almost all democratic theorists, cannot resist Brennan’s conclusion on intrinsic proceduralist grounds. Rather, they must reject his argument on instrumentalist grounds, and must therefore engage in difficult moral and empirical questions about the instrumental quality of procedures. Moreover, if Brennan’s argument cannot be refuted on instrumentalist grounds, then almost all democratic theorists would be committed to massive and controversial institutional reform. This would be hugely practically important finding of democratic theory.

It should be said before I proceed that HSI is only potentially practically important. If it turns out that there are no available superior undemocratic procedures, then no major institutional reform is required. However, although it is it is unclear whether there are superior undemocratic procedures, there is some reasonable chance that there are. So, HSI is potentially practically important in the sense that it has reasonably high expected practical import, which is compatible with it having no actual practical import.

3 Pervasive High Stakes Errors

Many democratic theorists appear to assume that at least in rich democracies, high stakes errors are avoided: basic rights are usually protected. Rich world democratic governments might not meet the demands of the more exacting prioritarian or egalitarian duties of justice, but they do not regularly violate their minimal sufficientarian obligations. They do not, for example, regularly violate rights to subsistence or rights to life. Therefore, HSI does not require us to find out whether there are instrumentally superior alternatives to democratic procedures.

I will argue that the foregoing line of thought is unsound. I will defend a thesis I call:

Pervasive High Stakes Democratic Errors (PHSE) – All extant democratic states frequently produce high stakes errors in most areas of policy.Footnote 7

I understand an ‘area of policy’ in a commonsense way. Areas of policy include transport policy, drug policy, health policy, foreign policy etc.

I will defend PHSE by considering a range of examples of democratically produced high stakes errors. In my discussion, I attempt to be as ecumenical as possible between different theories of substantive justice. Thus, the examples I discuss fall into two categories. In the first – drug policy, foreign policy, and climate policy – are cases which all reasonable moral theories agree involve high stakes errors. In the second – the lack of regulation of factory farming, insufficient foreign aid, and immigration control – are cases which at least the vast majority of reasonable moral theories agree involve very high stakes errors. Moreover, this is a non-exhaustive selection of examples of high stakes errors about which there is complete or near complete reasonable agreement. There are a whole host of other contemporary democratically-produced laws which all or nearly all reasonable theories agree to involve high stakes errors.

Note that I use reasonable here in the ordinary sense and not in the sense used by ‘public reason’ theorists. A reasonable moral or political theory is roughly one that does not make obvious and gross moral mistakes, and is resilient to some amount of rational criticism. I appeal to examples about which there is near or complete reasonable consensus for two reasons. Firstly, complete or nearly complete reasonable agreement on a proposition is strong evidence for the truth of that proposition. So, the examples provide strong reason to believe that the cases do in fact involve high stakes errors. In addition, on the basis of the arguments for the specific theory of justice I personally endorse, I also believe that all of the examples in fact involve high stakes errors. Secondly, philosophical proponents of hybrid theories themselves endorse reasonable conceptions of substantive justice.Footnote 8 So, independently of whether reasonable consensus on PHSE provides reason to believe PHSE, hybrid theorists have subjective reason to accept PHSE because they endorse it from the point of view of their own theories of substantive justice.

3.1 Drug Policy

Drug policies imposed in a range of contemporary democracies are severely unjust. This is for two main reasons. Firstly, the penalties imposed on drug users are very disproportionate to the harms of many of the drugs themselves. For example, in Florida, selling 10 g of ecstasy is punishable by a minimum sentence of 3 years and a maximum sentence of 30 years.Footnote 9 Selling 10 g of ecstasy is roughly as dangerous as selling 20 scuba diving lessons (Blastland and Spiegelhalter 2013, 293).Footnote 10 A single episode of acute harm results every 10,000 exposures to ecstasy. An episode of acute harm occurs every 350 exposures to horse riding (Nutt 2009).Footnote 11 In general, for paternalistic reasons, democratic societies impose stiff penalties on activities like consuming marijuana, magic mushrooms, ketamine, ecstasy and LSD, which are less dangerous than many legal activities such as horse riding, motorbike riding, and consuming alcohol and tobacco. In many democratic countries, this has led to a massive increase in the prison and jail population. For instance, in the USA, as of 2010, 560,000 people were in jail or prison for non-violent drug offences (Schmitt et al. 2010). Given the relative harms of illegal drugs, this punishment is clearly severely unjust. Comparably, all reasonable theories of justice would agree that a world in which, say, millions of people were in prison for consuming tobacco, alcohol or coffee would be severely unjust.

Secondly, drug prohibition creates massive externalities in terms of crime and other forms of violence. Just as alcohol prohibition in the US caused a massive increase in organised crime and violence, drug prohibition continues to cause a great deal of crime and violence in rich democracies and huge violence in drug-producing countries (Harp 2010). For instance, around 30,000 people have died in Mexico’s drug war.Footnote 12 In spite of these facts, drug prohibition is very popular across the world.Footnote 13

3.2 Foreign Policy

Lives are at stake in decisions about whether to go to war. Errors in this domain can easily lead to high stakes errors. Some democratically-produced foreign policy has been severely unjust. The war on terror is one such example. This graph shows the number of US fatalities from terrorist attacks between 1968 and 2010Footnote 14:

In the direct aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks, US popular support for the invasion of Afghanistan, as part of the ‘War on Terror’, was very high (Gallup 2014). The decision to invade Iraq in 2003 was also very popular among Americans (Pew Research Centre 2015). Over 6800 American servicepeople have been killed as part of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.Footnote 15 At least 170,000 civilians have been killed in the war on terror in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The war has cost the US government more than $1 trillion, and this is expected to grow to at least $4 trillion in the future. If the aim of the US government was to counteract terrorism, the war on terror appears to be a disproportionate and grossly irrational policy. If a policy kills 55 times as many people as the problem it was supposed to solve, there is good prima facie reason to believe that the policy has been a catastrophic mistake.Footnote 16 The policy also appears to be a clear error from a purely humanitarian point of view. The outcome of the $4 trillion spent on the war on terror is likely to be strongly negative or close to negative, in humanitarian terms. That money could have been spent on research into malaria, an HIV vaccine, or new antibiotics. These projects have a good chance of having very large humanitarian benefits. Therefore, the war on terror is simply impossible to justify from the humanitarian point of view. There are doubtless many other cases of clearly severely unjust democratically-produced foreign policy.

3.3 Climate Policy

It is extremely likely that increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere are causing global warming and climate change (Oreskes 2004). The costs to current and future generations of climate change are likely to be very high (Stern 2008). Perhaps most importantly, increasing greenhouse gas concentrations create a non-negligible (>1 %) risk of warming in excess of 6 °C, which could bring planetary catastrophe (Wagner and Weitzman 2015).

Many democracies have failed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with the limited demands of the Kyoto Protocol.Footnote 17 According to all plausible theories of justice, the failure of modern democracies to abate greenhouse gas emissions is severely unjust. Even those who endorse strongly nationalist theories of justice do not accept that nations have rights to impose massive externalities on third parties or on future generations.

3.4 Factory Farming

Literally billions of animals go through factory farming each year. The conditions they face, which are to a greater or lesser extent permitted by all modern democracies, can best be described as horrific.Footnote 18 In America, nine out of ten pregnant sows live in gestation crates. These pens are so small that the pigs can hardly move, even though they are as intelligent as dogs and small children. Consequently, they show signs of severe depression. Pigs are castrated, their tails docked, their needle teeth clipped and one of their ears notched for identification, all without anaesthetic. In nature, pigs spend up to three quarters of their time foraging and exploring their natural environment, but in factory farms, they spend all their time indoors in constant pain, while they perpetually inhale the fumes of their own waste. Pigs on overcrowded factory farms have three times as much mycoplasma pneumonia, six times as much swine influenza and twenty nine times as much flu of another strain as those on less crowded farms.

Egg-laying and broiler chickens also experience dreadful abuse in factory farms. All chickens’ sensitive beaks are severed without anaesthetic. Broiler chickens are raised in huge windowless sheds which reek of ammonia. High ammonia levels give the birds chronic respiratory disease, sores on their feet and hocks, and breast blisters, and make some birds go blind. Moreover, the chickens are bred for unnaturally fast growth so they cannot stand for long periods. One study found that 26 % of broilers suffer chronic pain from bone disease. Broilers are put in electrified bath water, which is supposed to stun them. However, Peter Singer and Jim Mason estimate that around three million chickens per year are still conscious as they are dropped into tanks of scalding water.

The vast majority of, and plausibly all, reasonable moral theories entail that animals are at least due some moral consideration. Just as all reasonable moral theories would agree that it is severely unjust for a state to fail to institute some minimal animal welfare laws to prevent, say, the mass torture of dogs, they ought to accept that it is severely unjust for a state not to prohibit the massive torture of pigs, cows, chickens, and other animals, which occurs in factory farms. There might be strongly anthropocentric theories which say that animals have no rights whatsoever against mistreatment, but it seems unlikely to me that these could be classed as reasonable. A reasonable theory could hold that humans are much more important than animals and that in a choice between protecting a human right and any number of animal rights, we ought to protect the human right. But the regulation and abolition of factory farms does not involve this kind of conflict. Consumers would have to pay a higher price for meat or eat less meat, but this is not a rights violation and seems to be clearly justified on the basis that it prevents mass-scale torture.

3.5 Foreign Aid and Medical Research

In 2010, 902 million people lived on less than $1.90 a day (World Bank 2016). Few countries spend more than 1 % of their GDP on foreign aid.Footnote 19 In spite of its critics (Easterly 2006; Moyo 2008), foreign aid has many notable successes, especially in public health (Levine 2007). For example, foreign aid helped to eradicate smallpox, thereby saving at least 50 m lives until today, at a cost of $300 m (Fenner et al. 1988). The WHO’s diarrhoeal disease control program has helped to save millions of lives from diarrhoea-related illnesses by distributing oral rehydration therapy (Fontaine et al. 2007). Research funded by the British Medical Research Council helped us to discover new and incredibly cost-effective short-course chemotherapy treatments for tuberculosis (Murray 2004, 1183). These successes alone justify all foreign aid on average, even if all other aid had no effect (MacAskill 2015, chap. 3). According to aid sceptic William Easterly (2006), the West has spent $2.3 trillion on aid. Even if the net benefit of this $2.3 trillion was smallpox eradication alone, the money would have saved a life for $46,000. For context, the UK National Health Service considers saving a year of life for £30,000 to be good value (Devlin and Parkin 2004). Looking to the future, there are a number of interventions, such as micronutrient fortification and insecticide-treated bed nets, which are known with reasonable certainty to avert a Disability Adjusted Life Year for around $100.Footnote 20

Most voters in rich democracies favour decreasing the amount of foreign aid (YouGov 2015). This might be because they drastically overestimate the amount their governments spend on it. For example, 26 % of British citizens believe that it is one of the top 2–3 items of British government expenditure, when it in fact makes up only 1.1 % of government expenditure.Footnote 21

Even according to many anti-cosmopolitan theories of justice, we have minimal duties of assistance to ensure that distant needy strangers are sufficiently well-off.Footnote 22 Rich democracies are currently failing to meet even their sufficientarian duties. If foreign aid or medical research is a good means to fulfil these duties (as it has been in the past), then the current level of foreign aid and medical research spending and the direction of that spending by rich democracies are severely unjust, even on many non-cosmopolitan theories of justice. All rich democracies spend vast amounts of money on things which are trivial or harmful in comparison, such as war, imprisoning non-violent drug offenders, agricultural subsidies, and subsidies for the fossil fuel industry. It is very difficult to believe that we would not better meet our duties to the global poor by spending this money on deworming or researching an HIV or e-bola vaccine instead. On the vast majority of reasonable moral theories, the failure of rich democracies to fulfil their sufficientarian duties to the global poor is severely unjust.

3.6 Immigration Controls

All modern democracies threaten people with sanctions if they try to immigrate into those countries. They also forcibly evict illegal immigrants. From the point of view of the majority of theories of justice, today’s extensive immigration controls constitute a severe substantive injustice. There is an extremely strong consequentialist case for more open borders. Almost all economists believe that immigration is good for or at least does not damage native economies (Caplan 2007, 58–59). According to many economists, open borders would double world GDP (Clemens 2011). This would greatly improve the welfare of billions of poor people. Given the size of these potential benefits to the poor, there is also a strong egalitarian and prioritarian case for more open immigration.

One of the most important facts about immigration controls is that on almost all theories of coercion, they are a paradigm case of coercion: states threaten people with sanctions if they try to enter a territory (Abizadeh 2008).Footnote 23 Not only are immigration controls coercive, they are very harmful because they deny prospective immigrants the massive economic benefits of living and working in developed economies and so deny them the basic means of subsistence. On many contemporary theories of justice, this harmful coercion stands in need of a very strong justification. According to liberals and libertarians, immigration controls are straightforwardly a severely unjust violation of each person’s right to free movement, association and to engage in mutually beneficial voluntary transactions (Carens 1987).

Some philosophers have argued that this harmful coercion is justified for various different reasons, such as the preservation of culture and states’ duties to their own citizens.Footnote 24 Most reasonable moral theories would, however, deny that these considerations justify harmful coercion of millions. Even if states have duties to their own citizens, for these duties to justify the extensive immigration controls we see today, each state would have to value the welfare of foreigners at something very close to zero (Chang 1996). Most public debate about immigration indeed proceeds as though the welfare and rights of prospective immigrants does not matter.Footnote 25 This may be a popular approach, but it is extremely ethically dubious. The majority of reasonable moral theories hold that extensive immigration controls are amongst the most unjust laws in rich democracies today.

This completes my case for PHSE. It is not difficult to think of other examples of high stakes errors. Obvious candidates include: the failure to deal with catastrophic and existential risks, poor healthcare resource prioritisation, the prohibition of compensation for kidney donation, poor fiscal policy, poor road safety policy, laws against stem cell research, and the prohibition of genetically modified food. Moreover, the examples I have selected all involve rich democracies which have much better governance than do most low and middle-income democracies. It is very likely that low and middle-income democracies produce even more high stakes errors than rich democracies.Footnote 26

3.7 Are these Injustices Genuinely Democratically Produced?

One possible response to my argument in this section would be to argue that the errors I have discussed are not genuinely democratically produced. There are two problems with this. Firstly, there are strong reasons to believe that these policies are democratically produced. For most of the examples, I appealed to data from opinion polls demonstrating strong support for severely unjust policies. Of course, opinion polls are not perfectly reliable, but it is reasonable to say that they provide fairly robust evidence on popular support for different policies.

However, a policy could have widespread popular support without being democratically produced: a dictatorship could, for example, impose a very popular policy. In light of this, the way to test whether these policies are democratically produced is to ask if a change in expressed majority opinion would cause a change in these policies, as a result of the change in expressed majority opinion. Suppose that public opinion were to come out strongly in favour of drug legalisation, more open borders, the abolition of factory farms, and increased foreign aid. It seems clear that if this were to happen, policies in these areas would be very likely to change either immediately or after the next election, as a result of the change in public opinion. The reason for this is that in rich countries generally thought to be democratic, mechanisms are in place to ensure that policies change if the majority’s expressed wishes change. Some policies, such as climate change policy and animal welfare policy, might be more subject to undue influence from special interests, while others might be affected by strongly disproportionate voting systems. If this does occur, then this is indeed a violation of political equality and democracy. However, it seems that even for these policies, a large enough shift in public opinion would be likely to produce a change in policy, as a result of the shift in public opinion. The same cannot be said for issues which are completely controlled by undemocratic institutions. For example, even if the majority in the US were to favour preventing Hindus from practicing their religion, this would have no impact on policy, because freedom of religion is protected by the US Constitution.

Secondly and more importantly, even if it is true that these policies are not democratically produced, this does not affect my main conclusion which is that HSI requires a reorientation of democratic theory and is potentially hugely practically important for democratic theory and for our political institutions. Suppose that the injustices I have discussed are not democratically produced. The challenge the proponent of HSI would then face would be to find out whether alternative democratic procedures would avoid the currently occurring high stakes errors. Since public support for these unjust policies is strong, prima facie this seems like a difficult task. There must remain some prospect that undemocratic institutions are the only way to prevent the currently occurring high stakes errors. Therefore, democratic theory would still have to be reoriented towards instrumentalism.

4 Concluding Remarks

I have four concluding remarks. Firstly, as I mentioned in section two, I have not attempted to defend the truth of SUP. To defend SUP, one would need to defend two propositions: firstly, that there are no available democratic procedures which would, if used, avoid high stakes errors, and secondly that there exist undemocratic procedures which would prevent these high stakes errors. PHSE provides strong confirmation for the first proposition. These high stakes errors are very plausibly caused by mistaken popular beliefs about these policies. Since democratic institutions are, by definition, sensitive to popular pressure, this suggests that all available democratic institutions would also produce these high stakes errors. However, I have made no attempt to defend the second proposition and a comprehensive treatment of it must be given elsewhere.

Secondly, my argument here entails that democratic theory should be reoriented towards evaluating the truth of the second proposition. That is, it should move away from advocating for political equality for its own sake, and towards dealing with difficult questions about the instrumental quality of procedures. There are almost no democratic theorists who should believe that intrinsic proceduralist considerations render instrumentalist considerations irrelevant to whether we ought to make extensive use of undemocratic procedures. If there are available undemocratic procedures that prevent high stakes errors, then almost all democratic theorists must accept that this would render the ongoing use of democratic procedures unjustifiable. If, for example, experts would produce better drug policy than democracies currently do, then leaving drug policy in the hands of the majority is unjustifiable and we are morally obligated to turn these decisions over to experts.

Thirdly, it cannot merely be assumed that democracy is more instrumentally just than all alternative procedures. To defend that proposition, one needs to seriously engage with theories of substantive justice and the empirical literature. It is clearly unreasonable to hold, without presenting any evidence or argument, that switching from a largely intrinsic proceduralist justification of political procedures to a largely instrumentalist one has no chance at all of making any difference to the political procedures we ought to use. Indeed, many hybrid theorists already accept that there is a good instrumentalist case for undemocratic institutions like judicial review. So, they need to explain why matters are different with regard to other feasible undemocratic procedures. If judicial review is a good way to protect freedom of religion, then why is expert control of drug policy not a good way to prevent democratically-produced severe injustice in that area? Democratic theorists have yet to attempt to answer this question.

Finally, many of us hope that political philosophy serves some practical role by providing normative guidance to political actors. It cannot do this very well when there is philosophical disagreement. However, we should hope that the fact that certain conclusions are entailed by all or nearly all plausible theories of justice would have some weight in the policy debate, especially when these conclusions conflict with prevailing opinion. It is important that political actors are made aware of the implications of all leading democratic theories, especially when they are as potentially practically important as HSI.

Notes

On this see (Knight and Johnson 1997).

Waldron (1999, chap. 13) provides an excellent discussion of this issue.

Given the conceptual framework discussed in section 1, it is a conceptual possibility that an outcome could be substantively very bad without violating anything’s rights.

Of course, many very substantively unjust outcomes will also be very substantively bad, but the point is that for my purposes, high stakes errors are defined in the former terms not the latter.

Utilitarianism is a form of pure instrumentalism and so also implies that we ought to use undemocratic procedures in order to prevent mildly substantively bad outcomes.

Brian Barry (1995, 109) is one of the few philosophers to have explicitly denied PHSE.

There are perhaps exceptions to this. It is possible that some hybrid theorists hold unreasonable theories of substantive justice.

This is on the assumption that the 10 g will be divided up into eighty doses of MDMA.

Due to popular pressure, Professor Nutt was fired from the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs for putting forward the scientific view on the relative harms produced by different drugs (Nutt 2010).

The data here is from: http://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/terrorism-incidents.html.

All of the following figures are from http://costsofwar.org.

Much of this is borrowed from the philosopher Michael Huemer’s TedX Talk on Irrational Politics. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4JYL5VUe5NQ.

All of the information here is from (Rachels 2011). Rachels discusses other aspects of factory farms not covered here. For undercover video investigations of factory farms see http://www.mercyforanimals.org/.

The charity Givewell has very rigorous evidence on the effectiveness of different aid interventions. See http://www.givewell.org/.

For this and evidence other popular political misconceptions in the UK see: https://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/3188/Perceptions-are-not-reality-the-top-10-we-get-wrong.aspx.

Blake and Smith (2015) provide a good overview of different theories of global and international justice.

David Miller (2010) is the most prominent philosopher to deny this.

Huemer (2010) provides a good overview.

Public opinion in many countries generally favours reducing immigration. See for example (Pew Research Centre 2014)

For example, animals suffer even more horrific abuse in poorer democracies and homosexuality is illegal in many African and Middle Eastern democracies.

References

Abizadeh A (2008) Democratic Theory and Border Coercion No Right to Unilaterally Control Your Own Borders. Polit Theory 36:37–65

Ackerman BA (1980) Social justice in the liberal state. In: New Haven. Yale University Press, London

Arneson RJ (2004) Democracy is not intrinsically just. In: Dowding KM, Goodin RE, Pateman C (eds) Justice & Democracy: essays for Brian Barry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Barry B (1995) Justice as Impartiality. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Blake M, Smith PT (2015) International Distributive Justice. In: Edward N (ed) In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Spring 2015, Zalta

Blastland M, Spiegelhalter DJ (2013) The Norm chronicles : stories and numbers about danger. Profile Books, London

Brennan J (2011) The Right to a Competent Electorate. Philos Q 61:700–724

Brighouse H (1996) Egalitarianism and Equal Availability of Political Influence. J Polit Philos 4:118–141

Broome J (1991) Weighing goods : equality, uncertainty and time. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Buchanan A (2002) Political Legitimacy and Democracy. Ethics 112:689–719

Caplan BD (2007) The myth of the rational voter: why democracies choose bad policies. In: Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press, Woodstock, Oxfordshire

Carens JH (1987) Aliens and Citizens: The Case for Open Borders. Rev Politics 49:251–273. doi:10.1017/S0034670500033817

Chang HF (1996) Liberalized Immigration as Free Trade: Economic Welfare and the Optimal Immigration Policy. University Pennsylvania Law Rev 145:1147

Christiano T (2008) The constitution of equality: democratic authority and its limits. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Clemens MA (2011) Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk? J Econ Perspect 25:83–106

Cohen J (2009) Philosophy, politics, democracy : selected essays. In: Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press, London

Devlin N, Parkin D (2004) Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ 13:437–452

Dworkin R (2000) Sovereign virtue: the theory and practice of equality. In: Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press, London

Easterly W (2006) The white man’s burden: why the West’s efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. Penguin Press, New York

Estlund D (2008) Democratic authority : a philosophical framework. In: Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press, Oxford

Fenner, Frank, Donald A. Henderson, Isao Arita, Zdenek Jezek, Ivan Danilovich Ladnyi, World Health Organization, and others. 1988. Smallpox and its eradication.

Fontaine O, Garner P, Bhan MK (2007) Oral rehydration therapy: the simple solution for saving lives. BMJ 334:s14–s14. doi:10.1136/bmj.39044.725949.94

Gallup. 2014. More Americans Now View Afghanistan War as a Mistake. Gallup.com .

Gaus GF (1996) Justificatory liberalism: an essay on epistemology and political theory. In: New York. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Griffin CG (2003) Democracy as a Non–Instrumentally Just Procedure. J Polit Philos 11:111–121

Harp S (2010) Globalization of the US Black Market: Prohibition, the War on Drugs, and the Case of Mexico. NYUL Rev 85:1661

Huemer M (2010) Is There a Right to Immigrate? Soc Theory Pract 36:429–461

Knight J, Johnson J (1997) What Sort of Political Equality does Deliberative Democracy Require? In: Bohman J, Rehg W (eds) In Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. MIT Press

Levine R (2007) Case studies in global health : millions saved. In: Sudbury, Mass. Jones and Bartlett, London

MacAskill W (2015) Doing good better : effective altruism and a radical new way to make a difference. Guardian Books, London

May SC (2009) Religious Democracy and the Liberal Principle of Legitimacy. Philos Public Aff 37:136–170

Miller D (2010) Why Immigration Controls Are Not Coercive: A Reply to Arash Abizadeh. Polit Theory 38:111–120

Moyo D (2008) Dead aid : why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. Allen Lane, London

Murray JF (2004) A Century of Tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169:1181–1186. doi:10.1164/rccm.200402-140OE

Nutt D (2009) Equasy — An overlooked addiction with implications for the current debate on drug harms. J Psychopharmacol 23:3–5. doi:10.1177/0269881108099672

Nutt D (2010) Nutt damage – Author’s reply. Lancet 375:724. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60302-9

Oreskes N (2004) The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change. Science 306:1686–1686. doi:10.1126/science.1103618

Pew Research Centre, 1615 L (2014) Chapter 3. Most support limiting immigration. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/05/12/chapter-3-most-support-limiting-immigration/

Pew Research Centre, 1615 L. 2015. Public Attitudes Toward the War in Iraq: 2003–2008. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/2008/03/19/public-attitudes-toward-the-war-in-iraq-20032008/. Accessed March 19.

Rachels S (2011) Vegetarianism. In: Beauchamp TL, Frey RG (eds) In The Oxford Handbook of Animal Ethics. Oxford University Press, New York

Rawls J (1996) Political liberalism, New edn. Columbia University Press, New York; Chichester

Raz J (1998) Disagreement in politics. Am J Jurisprudence 43:25–53

Richardson HS (2002) Democratic autonomy: public reasoning about the ends of policy. In: Oxford. Oxford University Press, New York

Saunders B (2010) Estlund’s Flight from Fairness. Representation 46:5–17

Schmitt, John, Kris Warner, and Sarika Gupta. 2010. The high budgetary cost of incarceration. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/incarceration-2010-06.pdf.

Stern N (2008) The Economics of Climate Change. Am Econ Rev 98:1–37

Valentini L (2013) Justice, Disagreement and Democracy. Br J Polit Sci 43:177–199

van Parijs P (1996) Justice and Democracy: Are they Incompatible? J Polit Philos 4:101–117

Wagner G, Weitzman ML (2015) Climate shock : the economic consequences of a hotter planet. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Waldron J (1999) Law and disagreement. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Waldron J (2006a) Disagreement and Response. Israel Law Rev 39:50–68

Waldron J (2006b) The Core of the Case against Judicial Review. Yale Law J 115:1346–1406

Wall S (2007) Democracy and Restraint. Law Philos 26:307–342

World Bank (2016) Poverty & equity data. http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/home/

YouGov. 2015. YouGov | British amongst least generous on overseas aid. YouGov: What the world thinks. https://yougov.co.uk/news/2013/11/09/British-amongst-least-generous-overseas-aid/. Accessed March 19.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Laura Valentini, David Miller, and Dan McDermott for particularly helpful comments on earlier formulations of this argument in my doctoral thesis. I am also grateful to Philip Thomson for typically vigorous discussion of even more embryonic versions of the argument. The comments of an audience at the Harvard Graduate Political Theory Conference were also very helpful. Finally, I am especially grateful to two anonymous reviewers at Ethical Theory and Moral Practice for their perceptive comments, which have helped to make this paper significantly better.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Halstead, J. High Stakes Instrumentalism. Ethic Theory Moral Prac 20, 295–311 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-016-9759-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-016-9759-9