Abstract

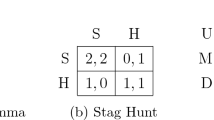

Aside from making a few weak, and hopefully widely shared claims about the value of privacy, transparency, and accountability, we will offer an argument for the protection of privacy based on individual self-interest and prudence. In large part, this argument will parallel considerations that arise in a prisoner’s dilemma game. After briefly sketching an account of the value of privacy, transparency, and accountability, along with the salient features of a prisoner’s dilemma games, a game-theory analysis will be offered. In a game where both players want privacy and to avoid transparency and the associated accountability, the dominant action will be to foist accountability and transparency on the other player while attempting to retain one’s own privacy. Simply put, if both players have the ability or power to make the other more accountable and transparent, they will do so for the same reasons that player’s defect in a prisoner’s dilemma game. Ultimately this will lead to a sub-optimal outcome of too much accountability and transparency. While there are several plausible solutions to prisoner dilemma games, we will offer both technical, as well as, law and policy solutions. We need to change the payoffs of the game so that is it in everyone’s interest to balance privacy and accountability rather than foisting transparency on others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Isaac Asimov, “The Dead Past,” The Complete Stories, Vol. 1 (Doubleday: Nightfall Inc. 1990), p. 40. See also, Arthur C. Clarke and Stephen Baxter’s The Light of Other Days (New York: Tor Books, 2000).

Plato, Republic, Bk. 2.

Adam D. Moore, “Privacy, Neuroscience, and Neuro-Surveillance,” Res Publica, 23, no. 2, 159–177. David Brin. The Transparent Society. New York: Perseus Books, 1998. David Lyon. Surveillance Society: Monitoring Everyday Life. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2001. See also Paul Ohm, “Broken Promises of Privacy: Responding to the Surprising Failure of Anonymization,” UCLA Law Review, 57, no. 6 (2009): 1701. Chris Jay Hoofnagle, “Big Brother’s Little Helpers: How ChoicePoint and Other Commercial Data Brokers Collect and Package Your Data for Law Enforcement,” North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation, 29 (2004): 595–637.

Samuel D. Warren and Brandeis Louis, “The Right to Privacy,” The Harvard Law Review, 4 (1890): 193–220.

Parts of this section draw from Adam D. Moore, “Privacy: Its Meaning and Value,” American Philosophical Quarterly, 40, no. 3 (2003): 215–227. For a rigorous analysis of the major accounts of privacy that have been offered, see Judith Wagner DeCew’s In Pursuit of Privacy: Law, Ethics, and the Rise of Technology (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), chaps. 1–4; Adam D. Moore, “Defining Privacy,” Journal of Social Philosophy, 39, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 411–228, and Privacy Rights: Moral and Legal Foundations (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), chaps. 2–3.

Viewing privacy as a “condition that obtains or not” is not a defensible account on our view. Consider how simple advancements in technology change this condition. What we care about is not if some condition obtains, but rather if we have a right that such a condition obtains. You may be able to use your x-ray device to look into private areas. The question is not a matter of “can,” it is a matter of “should.” Moreover, it is important to clarify the importance of privacy and accountability because it is this analysis that leads to the prisoner’s dilemma problem. For example, if privacy were simply nothing more than a mere subjective preference, if we are wrong about why privacy in morally valuable in the following section, then having no privacy could not be modeled as a suboptimal outcome within a prisoner’s dilemma. For a defense of this account of privacy see Adam D. Moore, “Privacy: Its Meaning and Value,” American Philosophical Quarterly 40, no. 3 (2003): 215–227, “Defining Privacy,” Journal of Social Philosophy 39, no. 3 (Fall 2008): 411–428, and Privacy Rights: Moral and Legal Foundations (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), chaps. 2–3.

S.I. Benn, “Privacy, Freedom, and Respect for Persons,” in Pennock, R. and Chapman, J. (eds.), Privacy Nomos XIII (New York: Atherton, 1971), pp. 1–26; Rachels, J. “Why Privacy is Important,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 4 (1975) 323–333; Reiman, J. “Privacy, Intimacy, and Personhood,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6 (1976), 26–44; J. Kupfer, “Privacy, Autonomy, and Self-Concept,” American Philosophical Quarterly, 24 (1987), 81–89; J. Inness, Privacy, Intimacy, and Isolation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992); B. Rössler, The Value of Privacy. Trans. Rupert D. V. Glasgow (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005).

See the sources cited in note 5. See also, Bryce Newell, Cheryl Metoyer, and Adam D. Moore, “Privacy in the Family,” in The Social Dimensions of Privacy, edited by Beate Roessler and Dorota Mokrosinska (2015).

For example, see Andreas Schedler, Larry Jay, and Marc F. Plattner, The Self-Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999); Kay Mathiesen, “Transparency for Democracy: The Case of Open Government Data,” in Adam D. Moore, Privacy, Security, and Accountability: Ethics, Law, and Policy, edited by A. Moore (Rowman & Littlefield International), December 2015), chap. 7; Nadine Strossen, “Post-9/11 Government Surveillance, Suppression, and Secrecy,” in Adam D. Moore, Privacy, Security, and Accountability: Ethics, Law, and Policy, edited by A. Moore (Rowman & Littlefield International, December 2015), chap. 12.

For a general analysis of trust and accountability see Onora O’Neill, “Reith Lectures 2002: A Question of Trust,” https://immagic.com/eLibrary/ARCHIVES/GENERAL/BBC_UK/B020000O.pdf (last visited 04/29/2020).

For example, they are not spouses, or Fred is not a police officer and Ginger is not a suspect. Also, as with the traditional prisoner’s dilemma game, moral norms, promises, and the like, play no central role in the analysis. For example, players may make agreements and the like, but this will not alter what is rational and prudent within the game.

Alas, there is a reason many online services are “free.” When some online service is offered for “free” the chances are it is your data that is being used as payment.

See, Robert Axelrod, “The Emergence of Cooperation Among Egoists,” The American Political Science Review 75 (1981): 306–318; Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984); and Brian Skyrms, The Dynamics of Rational Deliberation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

Thus, ratting is said to dominate staying silent and is a Nash equilibrium. “A Nash equilibrium is any profile of strategies—one for each player—in which each player’s strategy is a best reply to the strategies of the other players.” Ken Binmore, “Why all the Fuss? The Many Aspects of the Prisoner’s Dilemma,” in M. Peterson (ed.) The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Classical and Philosophical Arguments, vol. 20 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 16–34.

Pareto conditions are named after Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923) an Italian economist and sociologist.

See, Axelrod, “The Emergence of Cooperation Among Egoists;” and Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, 1984). For indefinitely repeated prisoner’s dilemma games tit-for-tat is a Nash equilibrium.

Pettit and Sugden offer a critique of this argument. See, Phillip Pettit and Robert Sugden, “The Backward Induction Paradox,” Journal of Philosophy, 86 (1989): 169–182. While the backward induction argument has been challenged in two-person iterated prisoner’s dilemmas with no known end point, it is not clear that such considerations hold in multi-player iterated prisoner’s dilemmas.

Garret Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162 (December 13, 1968): 1243–1248. See also, R. M. Dawes, “Formal Models of Dilemmas in Social Decision Making,” in M. F. Kaplan and S. Schwartz (eds.), Human Judgement and Decision Processes: Formal and Mathematical Approaches (New York: Academic Press, 1975), pp. 87–108; Xin Yao and Paul J. Darwen, “An Experimental Study of N-Person Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Games,” 18 Informatica, 435–450 (1994); and Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, (1994). Others have modeled public goods problems, like the tragedy of the commons, as assurance, chicken, or voting games. See Luc Bovens, “The Tragedy of the Commons as a Voting Game,” pp. 156–176 and Geoffrey Brennan and Michael Brooks, “The Role of Numbers in Prisoner’s Dilemmas and Public Good Situations,” in M. Peterson (ed.) The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Classical and Philosophical Arguments (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 177–198.

Garret Hardin, “Lifeboat Ethics: The Case Against Helping the Poor,” Psychology Today (September. 1974).

For a rich discussion of these issues, see Michael Taylor, The Possibility of Cooperation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); and Phillip Pettit, “Free Riding and Foul Dealing,” Journal of Philosophy, 83 (1986): 361–379.

For an interesting analysis of multi-player iterated prisoner’s dilemmas see Xin Yao and Paul J. Darwen, “An Experimental Study of N-Person Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Games,” Informatica, 18 (1994): 435–450.

See Michael Froomkin, “The Death of Privacy,” Adam Moore, ““Privacy, Security, and Government Surveillance: WikiLeaks and the New Accountability,” Public Affairs Quarterly, 25 (April 2011): 141–156; and Mike Katell and Adam Moore, “The Value of Privacy, Security, and Accountability,” in Privacy, Security, and Accountability, edited by A. Moore (Rowman & Littlefield International, December 2015), pp. 1–17.

It is also the true that sometimes the costs of unraveling outweigh any benefits in some cases. For example, the costs of disclosing past bad actions or assault related to the #MeToo movement would likely outweigh whatever benefits would be available. Thanks to Ofer Engel for this suggestion.

Scott Peppet, “Unraveling Privacy: The Personal Prospectus and the Threat of a Full Disclosure Future,” Northwestern University Law Review 105 (2011): 1153-1204. See also, Anita Allen, Unpopular Privacy: What Must We Hide? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Scott Peppet, “Unraveling Privacy,” p. 1181.

Robert H. Frank, Passions within Reason, (1988), p. 104. For an interesting analysis of signaling, information transfer, competitive games see Justin P. Bruner, “Disclosure and Information Transfer in Signaling Games, Philosophy of Science, 82 (2015): 649–666.

Elinor Ostrom notes “… the classic models have been used to view those who are involved in a Prisoner’s dilemma game or other social dilemmas as always trapped in the situation without capabilities to change the structure themselves. This analytical step was a retrogressive step in the theories used to analyze the human condition. Whether or not the individuals who are in a situation have capacities to transform the external variables affecting their own situation varies dramatically from one situation to the next.” Elinor Ostrom, “Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems,” Nobel Prize lecture (December 8, 2009): 416.

Peppet notes “Not all information markets unravel. Instead, unraveling is limited by transaction costs, ignorance of desired information, inability to accurately make negative inferences, and social norms.” Scott Peppet, “Unraveling Privacy: The Personal Prospectus and the Threat of a Full Disclosure Future,” (2011): 1191. See also, Annamaria Nese, Niall O’Higgins, Patrizia Sbriglia, and Maurizio Scudiero, “Cooperation, Punishment and Organized Crime: A Lab‐in‐the‐Field Experiment in Southern Italy,” IZA Discussion Papers 9901 (2016) https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/142340/1/dp9901.pdf. Nese et all note the norms adopted by various groups affect the willingness of players to cooperate or defect. “Camorra prisoners show a high degree of cooperativeness and a strong tendency to punish, as well as a clear rejection of the imposition of external rules even at significant cost to themselves . . . a strong sense of self‐determination and reciprocity both imply a higher propensity to cooperate and to punish . . .” p. 2.

Scott Peppet, “Unraveling Privacy: The Personal Prospectus and the Threat of a Full Disclosure Future,” (2011): 1196.

In working environments unionization may provide a way out of the unraveling problem. This idea was suggested by Ofer Engel at the Information Ethics Roundtable, Copenhagen 2018. See Simon Head, “Big Brother Goes Digital, The New York Review of Books, May 24, 2018, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2018/05/24/big-brother-goes-digital/#fn-11 (last visited 10/02/2018). Note that this solution will not work in other areas where unraveling occurs.

For example, Benndorf and Normann note that some individuals simply refuse to sell personal information for various reasons. Volker Benndorf and Hans-Theo Normann, “The Willingness to Sell Personal Data,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics (April 2017). See also, Volker Benndorf and Hans-Theo Normann, “Privacy Concerns, Voluntary Disclosure of Information, and Unraveling: An Experiment,” European Economic Review 75 (2015): 43–59. In this latter paper the authors note that unraveling occurred less than what was predicted.

See Ginger Jin, Michael Luca, and Daniel Martin, “Is No News (Perceived) Bad News? An Experimental Investigation of Information Disclosure,” Working Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2591450 (last visited 04/29/2020). Jin et al argue that information senders reveal less than what is expected and information receivers don’t assume the worst of those who don’t reveal.

See Laura Brandimarte, Alessandro Acquisti, and Francesca Gino, “A Disclosure Paradox: Can Revealing Sensitive Information Make us Harsher Judges of Others’ Sensitive Disclosures?” Working Paper, https://mis.eller.arizona.edu/sites/mis/files/documents/events/2015/mis_speakers_series_laura_brandimarte.pdf (last visited 01/17/18).

See Justin P. Bruner, “Disclosure and Information Transfer in Signaling Games, Philosophy of Science 82 (2015): 649–666.

For an analysis of consent related to employee privacy see Adam D. Moore, “Drug Testing and Privacy in the Workplace,” The John Marshall Journal of Computer & Information Law, 29 (2012): 463–492 and “Employee Monitoring & Computer Technology: Evaluative Surveillance v. Privacy,” Business Ethics Quarterly, 10 (2000): 697–709.

GDPR, Article 7/Recital 43 states explicitly that consent “should not provide a valid legal ground” when there is a clear imbalance between the parties. While this example is about a “data controller” who is also a public authority, the general idea is welcome. Thanks to Ofer Engel for this citation.

See David Gauthier, Morals by Agreement (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986).

For example see TrustArc’s Privacy Assessments and Certifications program. https://www.trustarc.com/products/certifications/ (last visited 04/29/2020).

Charles Holt, Cathleen Johnson, and David Schmidtz, Prisoner’s Dilemma Experiments, in M. Peterson (ed) The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Classical and Philosophical Arguments (Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 243–264.

“. . . the use of monitoring for control purposes will have dysfunctional consequences for both employees (lower job satisfaction) and the organization (higher turnover).” John Chalykoff and Thomas Kochan, Computer-Aided Monitoring: Its Influence on Employee Job Satisfaction and Turnover,” Personnel Psychology: A Journal of Applied Research, 42 (1989): 826, 807–834. See also, Roland Kidwell Jr. and Nathan Bennett, “Employee Reactions to Electronic Control Systems,” Group & Organization Management, 19 (1994): 203–218.

Lewis Maltby, “Drug Testing: A Bad Investment,” ACLU Report (1999), pp. 16–21.

Edward Shepard and Thomas Clifton, “Drug Testing: Does It Really Improve Labor Productivity?” Working USA, November–December 1998, p. 76.

Clay Posey, Rebecca Bennett, Tom Roberts, and Paul Lowry, “When Computer Monitoring Backfires: Invasion of Privacy and Organizational Injustice as Precursors to Computer Abuse,” Journal of Information System Security 7 (2011): 24–47. See also R. Irving, C. Higgins, and F. Safayeni, “Computerzed Performance Monitoring Systems: Use and Abuse,” Communications of the ACM, 29 (1986): 794–801 and J. Lund, “Electronic Performance Monitoring: A Review of Research Issues,” Applied Ergonomics, 23 (1992): 54–58. Whereas Irving et al found that electronic monitoring caused employees to report higher stress levels Lund found that such policies caused anxiety, anger, depression and a perceived loss of dignity. See also National Workrights Institute, “Electronic Monitoring: A Poor Solution to Management Problems” (2017), https://www.workrights.org/nwi_privacy_comp_monitoring_poor_solution.html (last visited 04/29/2020).

Matthew Holt, Bradley Lang, and Steve G. Sutton, “Potential Employees' Ethical Perceptions of Active Monitoring: The Dark Side of Data Analytics,” Journal of Information Systems: Summer, 31 (2017): 107–124.

See also, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa.

https://www.eugdpr.org/the-regulation.html. While many have warned that the right to be forgotten will undermine freedom of speech there is reason to believe that these worries are overblown. See Paul J. Watanabe, “Note: An Ocean Apart: The Transatlantic Data Privacy Divide and the Right to Erasure,” Southern California Law Review 90 (2017): 1111; Giancarlo Frosio, “The Right to be Forgotten: Much Ado About Nothing,” Colorado Technology Law Journal 15 (2017): 307–336. See also, “Privacy, Speech, and Values: What we have No Business Knowing,” Journal of Ethics and Information Technology 18 (2016): 41.

FTC v Wyndham Inc. 799 F.3d 236 (3d Cir. 2015).

Federal Trade Commission Act, Section 5: Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices (15 USC §45). https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cch/ftca.pdf.

Along with the suggested Wyndham rule we could also re-invigorate US privacy torts. William Prosser separated privacy cases into four distinct but related torts. “Intrusion: Intruding (physically or otherwise) upon the solitude of another in a highly offensive manner. Private facts: Publicizing highly offensive private information about someone which is not of legitimate concern to the public. False light: Publicizing a highly offensive and false impression of another. Appropriation: Using another’s name or likeness for some advantage without the other’s consent.” Dean William Prosser, “Privacy,” California Law Review 48 (1960): 383–389, quoted in E. Alderman and C. Kennedy, The Right to Privacy (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), pp. 155–156. While US privacy torts have been undermined by a series of cases, there have been suggestions to strengthen them. See for example Danielle Keats Citron, “Prosser’s Privacy at 50: A Symposium on Privacy in the 21st Century: Article: Mainstreaming Privacy Torts,” California Law Review (2010): 1805 and Adam D. Moore, Privacy Rights: Moral and Legal Foundations (2010), chap. 7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, A.D., Martin, S. Privacy, transparency, and the prisoner’s dilemma. Ethics Inf Technol 22, 211–222 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-020-09530-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-020-09530-6