Abstract

A significantly relevant issue that affects Black men in the workplace is a condition known as racial battle fatigue (RBF). RBF fosters systemic and systematic occupational and economic disparities that are experienced by Black men more regularly than their White counterparts (Smith et al., 2007). This qualitative study utilized a constructivist grounded theory methodology based on interviews with 11 Black male supervisors to understand the meaning of their cognitive and behavioral experiences as they navigated microaggressions, microinequities, and vicarious racism. These experiences contribute to our understanding of RBF. The findings revealed that Black male supervisors in various industries encountered and experienced RBF in the workplace. In addition, this research revealed that participants were subjected to various subtle and overt forms of racial stress due to microlevel and macrolevel RBF. The participants’ stories identified epistemic employment injustice and white fear as obstacles and barriers that Black men in supervisory roles face because of RBF in the workplace. The study also indicated that participants deployed managing and coping strategies to address the emotional contagions and emotional trauma resulting from their experiences. This research has implications for workplace policy change initiatives, cultural training and education, intergroup dialog courses, and clinical health practitioners. Recommendations pertaining to interventions that address trauma, mental health, and maladaptive behaviors are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“I’ve been doing this job for 18 years. I’m sitting here looking at guys that work at another company come in here and move up to a different level. And there are guys that I mentored getting promoted, so I asked “How the whole promotion thing works.“ I had to find out that they don’t recruit for positions; they just slot people into the positions where they want them. Once I spoke up, they looked at it and said, “Oh, we need to really kind of start looking for a position now because this guy’s asking a lot of questions.“ The corporation was like a boys’ club, and I wasn’t the right boy.“

This quotation was drawn from a participant in our research study, and it emphasizes a pattern observed in the careers of Black male supervisors where their ambitions were hindered by individuals who occupy positions of power and authority. During the interview, this participant recounted his story; he reflected on his disillusionment with his ambition for success in a company to which he had dedicated his intellectual capital for 18 years, resulting in a feeling of being at best tolerated while remaining underappreciated. The experiences of this participant and the other ten Black males in supervisory roles I interviewed are microcosmic examples of the broader racial experience of alienation, isolation, and disenfranchisement that these men face in the workplace. As a result, Black male supervisors encounter significant barriers to equity and inclusion in the workplace in academic, corporate, and government contexts due to the prevailing racial system that permeates these institutions.

The aforementioned situation exemplifies a prevalent issue in American culture regarding a significant disparity in representation. This disparity is evident from the fact that only eight individuals of color currently hold CEO positions in Fortune 500 companies (McGlauflin, 2023). Additionally, the National Football League’s reluctance to hire qualified Black coaches for head coaching positions, the underrepresentation of people of color in senior executive positions within the federal government (where White males constitute 78.8% of senior executives), and the recent promotion of the first black four-star general in the Marine Corps after 248 years of its establishment further accentuate the significance of this problem (Carter, 2022; Rigas & Kirk, 2020; Spain, 2020). These issues served as the impetus for our research, as the author and research team endeavored to comprehensively understand the fundamental challenges encountered in lower-level management. Within each of these industries, institutions, and organizations, Black men and people of color have encountered and continue to encounter, experience, and navigate race-related stressors (Jones & Neblett, 2019). Black males and individuals from diverse racial backgrounds commonly describe substantial encounters with race-related stressors, which take systematic, systemic, and personal forms (Jones & Neblett, 2019).

The topic under investigation in this research is the fact that Black men experience occupational and economic disparities that are both systematic and systemic and that position them below White men in terms of the opportunities available to them (Arnold et al., 2016; Castle et al., 2019; Nair et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2007). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black men are laid off at rates disproportionate to those faced by White men and earn 77.1% less than their White counterparts (Brundage, 2020). A field experiment on the economics of discrimination revealed that managers were willing to forego an average of 8% of their earnings to avoid hiring or promoting a member of another ethnic group (Hedegaard & Tyran, 2018). This report also revealed that Black managers experience a slower rate of promotion than their White manager counterparts. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, consistently rising unemployment rates and other forms of disparity demonstrate that Black men continue to face disadvantages, a situation which fosters Racial Battle Fatigue (RBF) (Nair et al., 2019). This work focuses explicitly on how Black male supervisors define and navigate their encounters and experiences with RBF in the workplace. Jones and Neblett (2019) asserted that race-related stresses are prevalent in professional environments. These race-related stresses strongly correlate with racism and discrimination and are a direct consequence of the phenomenon known as Racial Battle Fatigue (Kofi Lomotey & Smith, 2023).

Racism

According to Jones (1997), a famous researcher specializing in studies of prejudice and racism worldwide, it is multifaceted and systemically structured. Racism features five essential characteristics according to (Jones, 1997): (a) a conception of racial superiority or inferiority based on genetic differences; (b) extreme narcissistic devotion, cohesion, and hostility toward those outside the ingroup who do not share the ingroup’s values or ideals; (c) a set of rules that favor the powerful; (d) mental and behavioral qualities that are consistent with supremacist ideology in terms of the corresponding mental images, power institutions (political, economic, judicial, academic, and social), and belief norms; and (e) deliberate efforts to provide evidence for the legitimacy of racial differences and the usefulness of policies based on such perceptions. The vehicle used to perpetuate such ubiquitous racism can be summarized in terms of the construct of individual racism, which emphasizes superiority and power over people of color, constructs related to institutional racism, which pertains to systems, policies, and behaviors that disenfranchise people of color, and the extreme beliefs of cultural racism, which claim that the norms and perspectives of the dominant racial group are superior to those of people of the nondominant racial group (Jones, 1997). Racism is used to enhance the benefits and improve the social position of members of the dominant racial group while oppressing members of the inferior racial group in terms of their quality of life on both a systematic and an individual basis (Jones, 1997; Sue et al., 2007). Therefore, racism generates and triggers traumatic memories that represent historically haunting and violent perceptions of the past and activate the body’s memories when navigating the present (Smith et al., 2020).

Discrimination

According to Larnell et al. (2014), discrimination is systemic and linked to racism, biases, prejudice, and stereotypes. These factors significantly impact educational attainment, employment opportunities, disproportionate imprisonment rates, and violent treatment, leading to the dissolution of African-American families (Hadden, 2001). Discrimination at work is one of the most distressing and detrimental workplace behaviors that employees might encounter (Wingfield & Chavez, 2020). The perception of discrimination in the workplace is viewed as a strain-based emotional demand that contributes to increasing conflict between work and life (Minnotte, 2012). Discrimination perceptions, in particular, are brought to the forefront by placing workers in situations where such treatment causes moods and actions that extend beyond the walls of the workplace (Minnotte, 2012). In their seminal work, Feagin and Eckberg (1980) formulated a comprehensive framework for the fundamental aspects of discrimination. These dimensions encompass the underlying motivations that drive discriminatory behaviors, the actual implementation of such actions, the subsequent consequences that arise from discrimination, and the broader contextual factors that shape and influence discriminatory practices (Feagin & Eckberg, 1980). This contextual framework encompasses both the organizational setting in which discrimination occurs and the wider social environment in which it is deeply rooted.

Racial Battle Fatigue

William A. Smith, a social psychologist working in the field of education, coined the term Racial Battle Fatigue (RBF) in 2003 at a professional presentation at the American Educational Research Association. Smith (2004) focused on African-American professors’ experiences in predominantly white universities. Since this seminal publication, Smith has expanded this concept to explain the negative and racially charged experiences faced by all people of color in the United States (Corbin et al., 2018; Franklin et al., 2014; Smith, 2016, 2004; Smith et al., 2007). Quaye et al. (2019) also defined RBF as an exhaustive feeling that marginalized people face due to repeated exposure to racism and discrimination. The exhaustion associated with RBF involves a social-psychological stress response that includes frustration, anger, fatigue, physical avoidance, psychological or emotional withdrawal, escapism, and acceptance of the racist attributions associated with being a minority person (Wang et al., 2020).

Applebaum (2021) noted that RBF causes strain for marginalized and stigmatized groups, and the amount of energy that such groups expend coping with and fighting against racism and discrimination becomes exhausting. The experiences of people of color who endure RBF make it abundantly clear, according to Applebaum (2021), that these cumulative and subtle assaults are both unrelenting and ambiguous, to the point that naming the experience becomes a challenge to explain and confirm for individuals who do not experience or understand such indignities. Smith and Franklin et al. (2020) acknowledged that if racial discrimination were not adequately addressed, many Whites could easily establish additional or more substantial sociocultural and economic environments and resources that could shield them from race-related stressors and threats to their unearned racial entitlements.

Classification of RBF

Jones et al. (2020) identified five categories of race-related stressors: (a) racism-related life events (time-limited, specific life experiences), (b) daily racism microstressors (subtle slights and exclusions), (c) vicarious racism experiences (observing and reporting on the racism experiences of others), (d) chronic-contextual stress (social systemic and institutional racism), and (e) collective experiences (“cultural-symbolic and sociopolitical manifestations of racism,“ p. 46). The importance of naming these stressors became the focal point of our research, which was grounded in three of Jones et al.‘s (2020) five prominent types of race-related stressors that Black male supervisors encounter in the workplace. The classifications of microaggressions, microinequities, and vicarious racism emerged and were included in our study as subtle and covert race-related stressors that contribute to RBF in the workplace. Microaggressions are defined as instances of indirect, subtle, or unintentional discriminatory behavior perpetrated against members of marginalized groups, such as racial or ethnic minorities. Specific microaggressions include microinsults, microinvalidations, and microassaults (Sue et al., 2007). Microinequities are subtle, often unconscious messages that devalue, discourage, overlook, or impair workplace performance (Rowe & Giraldo-Kerr, 2017). Vicarious racism refers to the indirect experience of racial discrimination through close contacts, such as family members, peers, and coworkers, as well as via digital/social media (Levchak, 2019). These classifications are used as a foundation in this study to stimulate new lines of thought and research on these racerelated stressors rather than merely reusing the same concepts.

Literature Review: RBF in the Workplace

This literature review is presented as a thematic journey that is structured around different perspectives and debates concerning covert and subtle race-related stressors in the workplace. An extensive analysis of the scholarly literature that encompasses both the academic and corporate domains has identified a notable absence of research on the topic of RBF in business settings.

The notion of the workplace has been mentioned but has not been defined. Therefore, according to Brundage (2020), the United States Department of Labor, and our research, the workplace or place of employment is defined as a location where people perform tasks, jobs, and projects in various contexts for their employer. Fulton et al. (2019) claimed that the workplace is often the core site for social production and the perpetuation of social inequality. Although the United States is becoming more racially diverse, corporate elites remain disproportionately White, and this mismatch contributes to increasing racism (Fulton et al., 2019).

To improve our understanding of the roots of racism and prejudice in the United States, numerous studies and publications have been produced. The literature on this topic covers a wide variety of relevant theories. This review focuses on one central theme, i.e., the implications of disparity, which emerge repeatedly throughout the reviewed literature.

Pitcan et al. (2018) identified predominately white organizations (PWOs) as a microcosm where systems of racism and sexism in the United States culture reproduce and influence organizational practices and decision-making. The study explores the barriers faced by 12 Black men who worked in PWOs and found that they often face microaggressions, which can cause uncertainty and lead to difficulties in coping. The study revealed that these men experience psychologically challenging workplace interactions and career-related costs due to racial microaggression.

Gligor et al. (2021) reported that racism, prejudices, stereotyping, and discrimination exist in investor markets, leading to a higher bar for Black CEOs for advancement despite their exceptional qualifications. The choices of Black CEOs and Black members of top management were more unpopular with investors than those of White individuals. During the math scenario-based tests, it was common in investment bank and consultancy job interviews, and recruiting teams worried more when Black CEOs failed, and was unconcerned when White men failed the math test. When hired, on average, Black CEOs had more years of education, advanced degrees, and elite education than White CEOs under the same employment conditions (Gligor et al., 2021).

Ray (2019) focused on examining the influence of race on organizational behavior and posited that race plays a significant role in shaping the fundamental aspects, hierarchies, and operational mechanisms that characterize organizations. This scholar formulated four principles: (1) racialized organizations have the capacity to either empower or undermine the influence of racial groups; (2) racialized organizations validate the unequal allocation of resources; (3) whiteness functions as a form of qualification; and (4) the separation of formal regulations from actual organizational behavior is often influenced by racial dynamics. Ray (2019) concluded that including organizations in a structural framework for racial inequality might enhance our understanding of the durability, progression, and establishment of racial disparities within institutions. An earnest integration of race and organizational theory has the potential to offer a more effective framework for implementing interventions aimed at addressing the enduring presence of racist inequities inside organizations.

Pitcan et al. (2018) found that minority men in predominantly white organizations are more likely to experience and navigate race-related stressors in the workplace. Gligor et al. (2021) showed that despite their exceptional competencies, Black managers and executives in the investment industry are hindered by race, while Ray (2019) proposed combining race and organizational theory to address the inequities and inequalities faced by racialized groups, thus highlighting the implications of the theme of disparity. The literature on Black professionals, especially Black male supervisors in the workplace, is comparatively limited, and more attention to specific research on this topic and its meaning is necessary. The prevailing body of scholarly literature has suggested a fundamentally disruptive dynamic in the workplace that centers around racism, discrimination, and stereotyping, which, when combined, represent RBF, which is harmful to people in nondominant groups. The literature is incomplete due to its lack of an exploration of the patterns of behaviors that emerge and the development of appropriate managing and coping strategies that can raise awareness of the seriousness of this phenomenon.

Conceptual Framework

Critical race theory (CRT) is used to analyze the racial inequities that emerge from systemic racism and result from people’s thoughts and actions. Crenshaw, a leading academic working in the field of CRT, acknowledged that racism is a pervasive part of American culture (Crenshaw, 2011). According to Crenshaw (2011), the theoretical approach used in CRT investigates how a history of systemic and institutionalized racism has shaped American law. More specifically, this approach focuses on how American law makes racial hierarchy or illegitimate forms of racial discrimination possible (Fong, 2008). This study aimed to comprehend how Black male supervisors navigate their encounters with RBF in the workplace. The set of theories in alignment with this research was viewed through the lenses of cognitive appraisal theory (CAT) and symbolic interactionism theory (SIT) (Folkman et al., 1986; Griffin et al., 2015). CAT is in line with our research and research questions, which focus on the potential risk that emerges when an individual experiences a comment or situation and assesses that encounter as stressful and, in such a situation, the degree to which this encounter exceeds the individual’s ability to manage and cope (Folkman et al., 1986). SIT focuses on how individuals interact (Blumer, 1969). These theories posit that the meanings that people attribute to events and objects vary from person to person as well as time and indicate that these meanings drive people’s behavior.

Overall, this theoretical foundation aligns with the research’s approach, with CRT being used to examine the racial inequalities resulting from institutional racism. Concurrently, CAT is used to explore the stress that individuals experience when they must navigate stressful interactions, and SIT explores how individuals assign meaning to their encounters, which determines their behavior. Based on these concepts, CRT, CAT, and SIT are excellent complements to our research study and research questions. Our research aims to help Black men and people of color in supervisory roles discuss and better understand their experiences, report their perceptions, and uncover the pattern of behavior that emerges when navigating RBF while simultaneously capturing the strategies they use to manage and cope with these issues in the workplace.

Research Method

The research methodology employed in this study was based on grounded theory (GT). Grounded theory scholars have agreed that the formulation of a theory should be rooted in empirical data rather than preexisting literature. This approach involves a systematic, qualitative procedure that aims to produce a comprehensive conceptual understanding of a process, action, or interaction related to a significant topic of interest (Creswell, 2009; Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The research team employed the constructivist grounded theory (CGT) approach, which emphasizes and elicits participants’ understanding of their situations and the corresponding events and explores the assumptions, implicit meanings, and unspoken realities that are captured in the research questions (Charmaz, 2006). The constructivist component refers to the collaboration between the lead author/researchers and the participants with regard to constructing the emerging theory (Charmaz, 2006). The motivation for the use of CGT to conduct this research was to develop a theory based on real-world data because theory-based research that has examined the ways in which Black men in supervisory roles negotiate and navigate RBF remains scarce. It is important to note that the lead author/researcher has existential experience in this domain and chose to use a qualitative constructivist grounded theory method and design to obtain in-depth insights regarding the voices and experiences of Black men in relation to RBF with the goal of contributing to healthy management practices and promoting the ability to cope with this phenomenon while simultaneously increasing organizational awareness of RBF in the workplace. The research questions led the researchers to investigate how Black men in supervisory roles recognize episodes of race-related covert and subtle racism that forms RBF in the workplace, how they respond to or manage these episodes, and how they cope once such episodes occur. The following are the research questions and subresearch questions that guided the study:

Main Research Question

What meaning do Black men in supervisory roles ascribe to their encounters and experiences with racial battle fatigue in the workplace?

Subquestion 1

How do Black men in supervisory roles recognize, react, and respond to their encounters and experiences with racial battle fatigue in the workplace?

Subquestion 2

What strategies do Black men in supervisory roles use to manage the daily occurrence of racial battle fatigue in the workplace?

Demographics of Participants

The study participants included 11 Black or African-American males who were selected through purposive sampling and satisfied the criteria for answering the study question. The participants’ demographics, which are shown in Table 1, detail the participants’ levels of education, supervisory roles, and years as supervisors, as well as the industries in which they currently work.

Data Collection and Interview Questions

The data collected during in depth, semistructured interviews were systematically transcribed and imported using Dedoose, a qualitative research app, for analysis using purposive sampling. Once all 11 transcripts had been imported into Dedoose, they were positioned with respect to the anchor codes by reference to the factors (recognize, react, and response), classifications (microaggression, microinequities, and vicarious racism), strategies, and meaning-making methods associated with the research questions for further analysis. The interviews were conducted via the Zoom videoconferencing platform. Table 2 displays empirical data, which consists of samples of responses to the interview questions, alongside the participants’ experiences.

All participants responded openly to questions about their experiences, and several of them admitted that the interview session was cathartic. Participants were asked about their personal definitions of RBF, their experiences, and their stories regarding the workplace microaggressions, microinequities, and vicarious racism that constituted RBF.

Data Analysis

Participants were asked several open-ended, semistructured questions, and the transcripts were provided to participants for verification. We used the CGT approach and created codes using an interpretation-focused coding strategy consisting of a three-step coding cycle: initial, focused, and theoretical. This process also involved reflexivity, memoing, data reduction, and theoretical sensitivity. To facilitate the data analysis, we assessed the characteristics of each code, performed reductions, reviewed commonalities, and constantly compared the data throughout the process of analysis. We utilized the resulting codes and categories to develop themes for theoretical sensitivity, which focused our attention on each category and the research questions, thus enabling us to understand the possible relationships that could be established between an emerging theme and theory in further depth. The coding cycles presented a notable obstacle with regard to integrating and applying the research inquiries pertaining to the identification, response, reaction, managing, and coping techniques within the context of psychological, behavioral, and physiological impacts concurrently. This task was accomplished by linking the psychological and behavioral effects to the factors of recognizing, reacting, and responding within the domains of cognitive and behavioral operations associated with navigating the three classifications (microaggression, microinequities, and vicarious racism), while the physiological effects were in line with Vines et al.‘s (2006) concept, which explains that stressors alone do not affect health; instead, the managing and coping mechanisms that are used when facing racism affect the physical health outcomes exhibited by persons of color.

Considerations Regarding Biases

A researcher’s reflexive memos can help identify the personal assumptions, biases, and suppositions inherent in their data (Charmaz, 2014). Using reflexive memoing during the research experience, decoding the data, and capturing questions regarding the process facilitated a more effective interrogation of the researcher’s own thinking about the study. Awareness of the researcher’s positionality and bias with regard to the problem investigated in this study was crucial to the robustness of the empirical findings. The research team assessed themselves in terms of the predispositions of the research study and their previously established beliefs and refrained from manipulating the research data and producing biased interpretations thereof (Darby et al., 2019). A pilot test was conducted to ensure the research instrument’s validity and to verify that the iterative process of the constant comparison of the data was reliable and consistent with the research methodology.

Ethical Considerations

The names of all 11 participants were changed and replaced with a unique alphanumeric identifier to safeguard their identities and maintain confidentiality. All subjects provided informed consent for their participation in the study.

Research Findings

This article presents the research results and a discussion of the emerging findings. The analytical results of the study took the form of empirical indicators of relevant data that generated 1,168 codes drawn from the interviews with the 11 participants, which were uploaded into Dedoose; this process led to the emergence of 2,923 codes that were reapplied to the research question anchor codes (Adu, 2019). The anchor codes of the research questions were structured into two domains:

(1) Cognitive and behavioral operations based on recognizing, responding, and reacting alongside the strategies used for managing, coping, and meaning-making.

(2) Navigating the three classifications, including microaggressions, microinequities, and vicarious racism, to include adaptive strategies from the relevant classification.

The interpretive analyses identified the microaggression-related factors associated with recognizing, responding, and reacting (68 significant codes were identified); the microinequity-related factors associated with recognizing, responding, and reacting (39 significant codes were identified); and the vicarious racism-related factors associated with recognizing, responding, and reacting (26 significant codes were identified). In order to facilitate the data analysis, the researchers assessed the characteristics of each code, reviewing commonalities among individual codes and groups based on their shared characteristics to devise different categories based on the research questions.

As a result, the interpretation of the interviews and data development from Table 3 provides examples of datasets containing empirical data collected from participants’ experiences and translated into codes, highlighting the importance of consistent discourse and data organization to address the research question. Individuals and their environment categorize their encounters and experiences to determine their coping strategy, which depends on how the situation is appraised (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The deductive method was used to construct assumptions predicated on existing theories, which in our study were RBF, CRT, CAT, and SIT, and then gather the data to test those predictions to determine whether the data acquired lends credence to the categories and the theory (Halpin & Richard, 2021).

The framework was subsequently divided into two domains: (1) the cognitive and behavioral operation of the aforementioned factors (recognize, respond, and react) and (2) navigate (the three classifications: microaggression, microinequities, and vicarious racism). The linkage between Tables 3 and 4 was enhanced, thus making it easier to identify recurring codes and categories based on the more evident pattern that emerged, which was a significant improvement. Table 4 provides examples of the reduction of the datasets alongside the participants’ experiences, which were translated into codes.

Four themes emerged from the core question of meaning-making throughout the participants’ years of personal and professional workplace interactions: (1) Black male supervisors are not immune to racism; (2) Be exemplary; (3) Carry your race; and (4) Develop resiliency. These themes were synthesized without category development into a statement that accurately conveyed the participants’ understandings and interpretations of the meaning of their RBF experiences in Table 3. The respondents revealed that they each had their own individual behavior styles with regard to navigating RBF in the workplace, which were typically complex. The cumulative nature of their RBF encounters and experiences contributed to increased cognitive and behavioral responses, leading to health concerns regarding the implementation of management and coping strategies.

Ultimately, participants’ collective responses suggested that the cognitive and behavioral operations involved in navigating the three RBF classifications are both cumulative and an exhaustive experience. Black men’s experiences of RBF in the workplace as supervisors were conveyed through theoretical coding and by applying the framework based on CRT, CAT, SIT, and CGT to interpret, make, and enact the meaning and actions revealed by the study (Groen et al., 2017). The use of inductive and abductive approaches to the empirical data substantially facilitated the interpretation of the research question; accordingly, certain patterns that were either novel or surprising emerged with regard to navigating participants’ cognitive and behavioral activities and adaptive strategies (Halpin & Richard, 2021). Theoretical sensitivity was used when defining the relationships between the initial and focused codes and their relations to categories in ways that were conducive to consolidation, which influenced the development of both theme and theory.

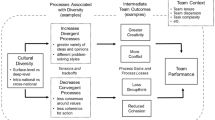

The themes that thus emerged—disconnection, deception as a hindrance, emotional decision-making, and dialog aimed at cooperation—answered the research question. Figure 1 depicts the 4D theoretical model of the cognitive and behavioral operations associated with the three classifications that emerged from this process.

Disconnection, dialog, decision-making, & deception model (4D model)

The participants’ statements are used as a unifying diagram for the 4D model of their RBF experiences as Black male supervisors. The four-relational model postulates a spatial perspective featuring five (5) aspects of the complexities of RBF situations that lie beyond the scope of a typical supervisor’s experience. The research findings and the 4D model highlight the abstract workplace environment in which Black male supervisors find themselves and in which they must navigate their unusual circumstances in a four-relational dimensional context

The analysis revealed concurrent, embedded, and causal relationships among the factors associated with the three classifications and the cognitive and behavioral operations domains. Based on the participants’ reports and experiences, both cognitive and behavioral operations and navigating exist or happen simultaneously, thus exhibiting a concurrent relationship. The embedded relationships also occur simultaneously in situations in which participants reported emotions and communication as fundamental influences, leading to the adjustment of other concepts, such as cognitive behavioral operations and classifications.

The themes indicated the baseline of the research questions: Black men in supervisory roles who encounter and experience microaggressions, microinequities, and vicarious racism in the workplace endure stress in a way that can be captured by a four-relational model (4D). This model describes the cognitive and behavioral flow exhibited by Black bale supervisors who must navigate RBF. The manifestation of RBF causes internal and external (conscious and subconscious) disconnects within the workplace, thus triggering an array of emotional debates regarding whether to engage in dialog concerning the incident. Depending on the severity of the RBF incident(s) in question, primarily when microinequities occur overtly when the supervisor is overlooked for advancement, an additional disconnect occurs, and emotional decisions become necessary regarding whether to maintain workplace decorum or to confront the matter and whether to trust the dialog or to discover that deception has masked the truth.

The Black men in supervisory roles who participated in this study shared their experiences with obstacles and barriers, such as being overlooked for promotions, not receiving credit for their efforts, and working more diligently to be exemplary than their colleagues because they were the only Black men at that supervisory level. The reality of deception and hindrance emerged as a core theme because of its relevance and explanatory power with regard to problematic behavior, which participants highlighted in the empirical data. In the areas of strategies and adaptive practices and techniques, the participants did not indicate that they suffered from severe physical health issues or physical ailments associated with RBF, such as high blood pressure or heart issues. Insomnia, overeating, weight fluctuation, and exhaustion were the relatively few physiological complaints reported by the participants with regard to the physical manifestations of RBF. These results reflect the approach of John Henryism, according to which participants minimized their health concerns due to their inherent need to be competitive, aspire, and survive by working more diligently because of the sacrifices their Black parents and African ancestors had made (Moore, 2021). Their drive for success was based on their need to cultivate a better future for the next generation of Black male supervisors. Participants employed religious practices such as prayer and inspirational gospel music, made mental notes of disingenuous exchanges with management, engaged in silent screaming, clamped their hands together tightly, participated in support teams/groups, and employed self-medication as strategies to manage and cope with RBF in the workplace. Synthesizing and coconstructing these recollections into a broader theoretical interpretation, model, and narrative illustrates the complexities and unique aspects associated with Black males in supervisory roles and their experiences of RBF at work.

Summary of Findings

The study’s findings revealed the existence of microaggressions, microinequities, and vicarious racism in the form of the RBF that Black men in supervisory roles encountered and experienced in the workplace. This study emphasized the tenacity of Black men in supervisory roles and the successful navigating strategies they used in response to the persistence of subtle race-related stressors. The 11 participants recalled being the only Black male supervisor at a key leadership level for most of their careers. Their roles as Black male supervisors allow them to promote diversity and challenge the dominant group’s status quo as the only such figure. Finally, participants expressed annoyance with the mistrust they had encountered regarding their qualifications, academic institution, and technical expertise when performing their jobs.

Interpretation of Findings

The study aimed to encourage Black men in supervisory roles to discuss scenarios that involved conditions or processes that highlighted a sequential pattern of behaviors that were relevant to their experience. By revisiting the 4D model with an emphasis on the emergent theory of deception as an obstacle to progress, the researchers reflected on Applebaum’s (2021) article titled RBF: Epistemic Exploitation and Willful Ignorance, which proposes a theory of contributory injustice. This theory broadens the analysis to account for a pattern of behavior grounded in the participants’ experiences that is comparable to epistemic injustice, according to which marginalized groups are disregarded or ignored when they attempt to navigate injustice (Bailey, 2014). The iterative examination of the participants’ experiences focused on the macrolevel spectrum of the RBF theme of deception as an obstacle to progress. This was in line with our exploration of the concept of contributory injustice, which led to the finding of “white fear” in this context. The focus on “contributory” emphasized the role of willful ignorance as a contributing factor to a dominant framework of protection based on questioning and challenge (Applebaum, 2021, p. 60). White fear represents a subset or branch of contributory injustice because members of the privileged group within the system are collectively complicit in preventing members of the nonprivileged group within the system from being able to prove that harmful patterns of racism are pervasive and tiresome based on a lack of engagement with members of the latter group to address those patterns (Applebaum, 2021).

According to Booysen (2007), white fear is a primary reason why management, mainly white management, is opposed to effective employment fairness. White fear is based on a loss of power and privilege, which is critical of whiteness (Donnor, 2021). The participants’ explanations of the conditions of epistemic injustice in employment revealed the presence of white fear. This fear contributes to the heightened challenges faced by Black men and people of color who are marginalized in expressing their encounters and experiences with RBF. A clearer explanation of this notion is that when “the powerful have an unfair advantage in structuring resources,“ epistemic employment injustice emerges (Applebaum, 2021, p. 62).

An unusual observation that emerged when abduction was applied necessitated a theory that fit into previously established theories to account for these findings. The theory of epistemic employment injustice depicted in Fig. 2 emerged unexpectedly from the participant’s perspectives. As a result, white fear was discernible as it manifested in the execution of discriminatory employment practices, which further intensified the participants’ maladaptive behavior as a consequence of their encounters with RBF. The contextual specificity of our research, the absence of additional factual research relevant to the participants, and the construction of this theory, regardless of how minor or marginal it may be, were in line with the participants’ experiences. The emergent theory was interpreted such that the participant’s experiences were composed of three factors that exhibited a pattern of injustice that is both systemic and systematic.

This pattern of injustice entails that individuals with privilege participate in resolving, dissolving, and absolving inclusivity, thereby creating intentional barriers associated with a feedback loop as a restoration of the status quo. The dominant group engages in the institutionalized practice of epistemic employment injustice by excluding entrants who are incongruent with the culture or the dominant group norms by deciding firmly on a course of action to hinder entry. Subsequently, the dominant group dissolves the possibility of entry through deception, resulting in a disparity of opportunities, as shown in Fig. 2.

Throughout this process, privileged practitioners in the dominant group are careful to absolve the organization from blame and responsibility by relying on interpretative processes, procedures, and policies. As a result of these systemic and systematic practices, dominant groups restore their position of power and privilege.

Limitations

This study aimed to investigate the experiences of Black male supervisors in the workplace who have successfully navigated subtle and covert racial-related stress. A number of different factors limit the findings of this study, such as those pertaining to participants, the literature, the research methods used, the data analysis, and the overall study. Due to the qualitative nature of the study, its small sample size of 11 Black men in supervisory roles, and the GT approach it employed, its findings cannot be generalized to all industries or organizations in the United States. The study focused on Black male supervisors with a bachelor’s degree or higher who have successfully navigated racial-related stress and have the capability to manage their experiences with racism. However, some participants were not familiar with the terms RBF, microinequities, and vicarious racism, even though they experienced them daily. Before the interviews, the researcher presented definitions to explain these terms to the eligible participants. This approach could have affected how the participants answered the interview questions since they may have answered in a way that would help achieve the goals of this study. The sample size of 11 participants may have limited the richness of the data the study may have provided.

Gathering literature on RBF in an organizational workplace setting was challenging due to the scarcity of such research. Most of the information in the literature was drawn from academic sources rather than from the public or private sectors. The researchers were required to make certain assumptions based on the literature, which focused more on the plight of women, students, and faculty, to adapt these insights to Black men in supervisory roles based on articles from peer review journals in the field of psychology. This situation represented a significant constraint in the context of a Black male supervisor in the workplace. Future researchers can make the necessary improvements to mitigate the limitations identified in this research.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This qualitative grounded theory study aimed to answer the following research question: What meaning do Black men in supervisory roles ascribe to their encounters and experiences with racial battle fatigue in the workplace? The findings that thus emerged provided us with knowledge of the textural and empirical lived experiences of Black male supervisors who worked in a variety of large industries and organizations in the United States and experienced RBF. This study is important to organizations because a great deal of time, money, and other resources are invested in recruiting, hiring, training, and evaluating employees. The findings of this study are significant because they pertain to organizational culture, employee well-being, employee empowerment, leadership, diversity, equity, and inclusion in this context. Retention is vital to an organization’s livelihood because organizations recognize that success in these areas leads to a healthy and productive workplace, which can positively impact their bottom line. Based on the findings of this study, future research is recommended to address the issue of the experience of RBF by Black men serving in supervisory roles in the workplace, which requires a holistic investigative approach.

Recommendations

The recommendations made in this section emphasize the important ways in which leaders and practitioners can benefit from reading and taking advantage of the study’s findings. The significance of a company’s culture, employee well-being, employee empowerment, leadership, diversity, equity, and inclusion awareness and execution cannot be overstated. It is imperative for leaders and human resource practitioners to possess a comprehensive understanding of RBF and its impact on Black male supervisors. This understanding is crucial to effectively establish standards for conduct and managerial knowledge. A full understanding of this issue could help reduce the costs of absenteeism, turnover, and lawsuits (Title VII) and create a healthier and more authentic workplace environment in which people of color can aspire to leadership positions. Unfortunately, organizations overlook the misuse and abuse of direct hiring practices and Schedule A hires and make subjective judgments regarding performance appraisals. Additionally, organizations create new diversity programs featuring gimmicky taglines while celebrating monthly awareness as an effective, productive diversity program rather than implementing an effective strategy, diversifying the leadership team, and reaping fundamental cost benefits. These organizations would benefit from analyses that include a policy that requires an employee climate survey, an audit of hiring practices, and advocacy for minority representation; accountability, consequences, and repercussions in cases in which evidence of unfair employment practices is discovered; and incentives, benefits, and advantages in response to effective inclusion practices. This approach would lead to employment and employer commitment, buy-in, and potentially an increase in the company’s leadership pipeline from the supervisor level to the senior executive level. The direct involvement of organizational leadership is imperative for policy implementation.

Leaders and human resource professionals define and influence policies, processes, and training reforms and provide a voice for Black males in supervisory roles who are excluded and treated as commodities. Regarding diversity and inclusion, workplace stereotyping and ingroup preference have been the subject of substantial research and documentation (Bardwell, 2013; Colella & King, 2018; Ghumman et al., 2016; Roberson, 2006; Sparkman, 2019). Knowledge of the differences in attitudes exhibited by members of marginalized groups is a crucial part of the system of institutions for overcoming discrimination, and leaders must be aware of these differences. (Triana et al., 2015).

This study expanded on existing knowledge of RBF to encourage a new wave of research and practice that can focus on the mental, physical, and emotional well-being of Black men and people of color at every level. Despite the apparent difficulties associated with this phenomenon, the answer to this problem does not lie in continuing to be perplexed and disheartened. Racial Battle Fatigue has the potential to reveal how specific resources and opportunities are structurally absent in our response to the effects of race-related pressures in the workplace among people in positions of power and marginalized people (Kofi Lomotey & Smith, 2023). Racism is undeniably the most critical, urgent, and intractable problem facing the United States of America. To create a healthy nation, we must heal our racial wounds. It is imperative that we continue to perform the accurate analysis that we have been conducting, that we document our findings, and that we put these findings into practice.

References

Adu, P. (2019). A step-by-step guide to qualitative data coding. Routledge.

Applebaum, B. (2021). Racial battle fatigue, epistemic exploitation, and willful ignorance. Philosophy of Education, 76(4), 60–77. https://doi.org/10.47925/76.4.060.

Arnold, N. W., Crawford, E. R., & Khalifa, M. (2016). Psychological heuristics and faculty of color: Racial battle fatigue and tenure/promotion. The Journal of Higher Education, 87(6), 890–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.11780891.

Bailey, A. (2014). The unlevel knowing field: An engagement with dotson’s third-order epistemic oppression. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, 3(10), 62–68.

Bardwell, S. H. (2013). Conflict and communication in the workplace: An inquiry and findings from Xyz university’s study on religious tolerance and diversity suggesting ironies of cultural attitudes, free expression and conflict in an academic organization. Journal of Organizational Culture Communications and Conflict, 17(2), 1–28.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and methods. Prentice-Hall.

Booysen, L. (2007). Barriers to employment equity implementation and retention of blacks in management in South Africa. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 31, 47–71.

Brundage, V. (2020). Labor market activity of blacks in the United States. Division of Labor Force Statistics), US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Carter, E. R. (2022). DEI initiatives are futile without accountability. Harvard Business Publishing.

Castle, B., Wendel, M., Kerr, J., Brooms, D., & Rollins, A. (2019). Public health’s approach to systemic racism: A systematic literature review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0494-x.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

Colella, A. J., & King, E. B. (2018). The Oxford handbook of workplace discrimination. Oxford University Press.

Corbin, N. A., Smith, W. A., & Garcia, J. R. (2018). Trapped between justified anger and being the strong black woman: Black college women coping with racial battle fatigue at historically and predominantly white institutions. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 31(7), 626–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2018.1468045.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2011). Twenty years of critical race theory: Looking back to move forward. Connecticut Law Review, 43(5), 1253–1346.

Creswell, J. (2009). Research design qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publication, Inc.

Darby, J. L., Fugate, B. S., & Murray, J. B. (2019). Interpretive research. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 30(2), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-07-2018-0187.

Donnor, J. K. (2021). White fear, white flight, the rules of racial standing and whiteness as property: Why two critical race theory constructs are better than one. Educational Policy, 35(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904820986772.

Feagin, J. R., & Eckberg, D. (1980). Discrimination: Motivation, Action, effects, and Context. Annual Review of Sociology, 6, 1–20.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992.

Fong, E. (2008). Reconstructing the problem of race. Political Research Quarterly, 61(4), 660–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908324588.

Franklin, J. D., Smith, W. A., & Hung, M. (2014). Racial battle fatigue for latina/o students: A quantitative perspective. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 13(4), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192714540530.

Ghumman, S., Ryan, A. M., & Park, J. S. (2016). Religious Harassment in the workplace: An examination of observer intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 279–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2044.

Gligor, D. M., Novicevic, M., Feizabadi, J., & Stapleton, A. (2021). Examining investor reactions to appointments of black top management executives and CEOs. Strategic Management Journal, 42(10), 1939–1959. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3284.

Griffin, E., Ledbetter, A., & Sparks, G. (2015). A first look at communication theory. McGraw-Hill International Education.

Groen, C., Simmons, D., & McNair, L. (2017). An introduction to grounded theory: Choosing and implementing an emergent method. In Paper presented at SEE Annual Conference & Exposition Columbus, Ohio. https://peer.asee.org/27582.

Hadden, S. (2001). Slave patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Harvard University Press.

Halpin, M., & Richard, N. (2021). An invitation to analytic Abduction. Methods in Psychology, 5, 100052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2021.100052.

Hedegaard, M. S., & Tyran, J. R. (2018). The price of prejudice. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1), 40–63. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150241.

Jones, J. M. (1997). Prejudice and racism. McGraw-Hill Companies.

Jones, S. C. T., & Neblett, E. W. (2019). The impact of racism on the mental health of people of color. In M. T. Williams, D. Rosen, & J. Kanter (Eds.), Eliminating race-based mental health disparities: Promoting equity and culturally responsive care across settings (pp. 79–97). Context Press/New Harbinger Publications. New Harbinger Books.

Jones, S. C., Anderson, R. E., Gaskin-Wasson, A. L., Sawyer, B. A., & Applewhite, K., & Metzger, I. W. (2020). From “crib to coffin”: Navigating coping from racism-related stress throughout the lifespan of Black Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(2), 267.

Kofi Lomotey, & Smith, W. A. (2023). The Racial Crisis in American Higher Education, Third Edition. State University of New York Press.

Larnell, G. V., Boston, D., & Bragelman, J. (2014). The stuff of stereotypes: Toward unpacking identity threats amid African American students’ learning experiences. Journal of Education, 194(1), 49–57.

Levchak, C. C. (2019). Microaggressions and modern racism: Endurance and evolution. Palgrave MacMillan Springer Nature.

McGlauflin, P. (2023). Black CEOs on the Fortune 500 reach new record high in 2023-meet the 8 executives. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2023/06/05/black-ceos-fortune-500-record-high-2023/.

Minnotte, K. (2012). Perceived discrimination and work-to-life conflict among workers in the United States. The Sociological Quarterly, 53(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2012.01231.x.

Moore, I. (2021). The influence of hegemonic (toxic) masculinity on leadership behaviors of Black men. In R. Johnson (Eds.), Handbook of research on multidisciplinary perspectives on managerial and leadership psychology (pp. 385–395). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-3811-1.ch018.

Nair, N., Good, D. C., & Murrell, A. J. (2019). Microaggression experiences of different marginalized identities. Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 38(8), 870–883. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-12-2018-0221.

Pitcan, M., Park-Taylor, J., & Hayslett, J. (2018). Black men and racial microaggressions at work. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(4), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12152.

Quaye, S. J., Karikari, S. N., Allen, C. R., Okello, W. K., & Carter, K. D. (2019). Strategies for practicing self-care from racial battle fatigue. Higher Education Policy for Minorities in the United States, 5(2), 95–131. https://doi.org/10.15763/issn.2642-2387.2019.5.2.94-131.

Ray, V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26.

research. Sage.

Rigas, M., & Kirk, D. (2020). OPM senior executive service desk guide. United States Office Of Personnel Management.

Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations.Group & Organization Management,31(2), 212–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104273064.

Rowe, M., & Giraldo-Kerr, A. (2017). Gender micro-inequities. In K. L. Nadal (Ed.),The SAGE encyclopedia of psychology and gender (pp. 679–682). Sage.

Smith, W. A., Allen, W. R., & Danley, L. L. (2007). “Assume the position… you fit the description” psychosocial experiences and racial battle fatigue among African American male college students. American Behavioral Scientist,51(4), 551–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207307742.

Smith, W. A. (2004). Black faculty coping with racial battle fatigue: The campus racial climate in a post-civil rights era. In Darrell Cleveland (Ed.), A Long Way to go: Conversations about Race by African American Faculty and Graduate Students (pp. 171–190). Peter Lang Publishers.

Smith, W. (2016). Understanding the corollaries of offensive racial mechanism, gendered racism, and racial battle fatigue. Center for Critical Race Studies at UCLA Research Brief.

Smith, W. A., Franklin, J. D., & Hung, M. (2020). The impact of racial microaggressions across educational attainment for African Americans. Journal of Minority Achievement, Creativity, and Leadership,1(1), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.5325/minoachicrealead.1.1.0070.

Spain, E. S. (2020). Reinventing the leader-selection process: The US army’s new approach to managing talent. Harvard Business Publishing.

Sparkman, T. E. (2019). Exploring the boundaries of diversity and inclusion in human resource development. Human Resource Development Review,18(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484319837030.

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M., Nadal,K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist,62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.62.4.271.

Triana, M. D. C., Jayasinghe, M., & Pieper, J. R. (2015). Perceived workplace racial discrimination and its correlates: A metaanalysis.Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(4), 491–513.

Vines, A. I., Baird, D. D., McNeilly, M., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Light, K. C., & Stevens,J. (2006). Social correlates of the chronic stress of perceived racism among Black women. Ethnicity & Disease,16(1), 101–107.

Wang, S. C., Hubbard, R. R., & Dorazio, C. (2020). Overcoming racial battle fatigue through dialogue: Voices of three counseling psychologist trainees. Training and Education in Professional Psychology,14, 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000283.

Wingfield, A. H., & Chavez, K. (2020). Getting In, Getting Hired, Getting Sideways Looks: Organizational Hierarchy and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination. American Sociological Review, 85(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419894335.

Fulton, B., Oyakawa, M., & Wood, R. (2019). Critical standpoint: Leaders of color advancing racial equality in predominantly white organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 30(2), 255–276.

Strauss, A., and Corbin, L (1990). Basics of grounded theory methods. Sage.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, T.J., Romosz, A.M., Roman, R.L. et al. Black Male Supervisors Navigating Racial Battle Fatigue: A Grounded Theory Approach. Employ Respons Rights J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09475-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-023-09475-0