Abstract

This article aims to contribute to the largely neglected issue of whether metaphysical grounding – the relation of one fact’s obtaining in virtue of the obtaining of some other (or others) – can be given a reductive account. I introduce the notion of metaphysically opaque grounding, a form of grounding which constitutes a less metaphysically intimate connection than in standard cases. I then argue that certain important and interesting views in metaphysics are committed to there being cases of opaque grounding and demonstrate that four representative accounts of grounding available in the literature are unable to accommodate such cases. This is argued to constitute a problem for those accounts that is likely to extend to other possible reductive accounts of grounding that employ the popular strategy of explaining grounding in terms of other hyperintensional phenomena. Unless the reductionist is willing to opt for some sophisticated modalist account, the possibility of opaque grounding cases thus provides indirect support for primitivism about grounding, a view that has previously been widely embraced but rarely supported by argument.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The last ten years or so have seen an explosion of work on metaphysical grounding. Grounding has been used to define intrinsicality (Witmer et al., 2005), to provide a reductive account of modality (Kment, 2014), and to articulate core ideas in feminist metaphysics (Schaffer, 2017; Passinsky, 2019) – to mention just a few applications. Friends of grounding have also vigorously debated various questions about how grounding works, such as whether it is a necessitating relation (Trogdon, 2013; Skiles, 2015), what grounds grounding facts themselves (Bennett, 2011; Litland, 2017), and whether there must be something ungrounded (Bliss, 2013; Schaffer, 2016). Meanwhile, skeptics have remained unimpressed, questioning the coherence and utility of the notion of grounding (Hofweber, 2009; Daly, 2012; Wilson, 2014; Koslicki, 2015). Critics frequently complain that grounding is rendered obscure by its supporters’ willingness to treat it as metaphysically primitive. For this reason, it is surprising that the available reductive accounts of grounding have not received more attention in the literature. A successful reduction of grounding could help alleviate skeptical concerns about obscurity, as well as provide the basis for systematic answers to many of the outstanding questions about how grounding works. Insofar as philosophers have tried to reduce grounding, it has typically been assumed that a successful reductive account will explain grounding in terms of some other similarly heavyweight hyperintensional phenomenon. However, in this article I wish to draw attention to a problem that faces four currently available reductive accounts and which would likely extend to any further contenders pursuing this hyperintensionalist strategy. The problem is the following: the accounts are incompatible with the possibility of opaque grounding cases, which are arguably entailed by some interesting and popular metaphysical theories.

I will proceed as follows: in Sect. 2, I will provide some clarifications necessary for the discussion to come. In Sect. 3, I will introduce the idea of opaque grounding. In Sect. 4, I will present four reductive accounts of grounding available in the literature and show how opaque grounding cases constitute a problem for all of them. In Sect. 5, I will consider some issues arising from the preceding discussion, including the question of how far the current argument generalizes.

2 Preliminaries

Let us start by getting more precise about our subject matter: reductionism about grounding. I take grounding to be the relation that is involved in or invoked by various non-causal explanations, such as the following:

-

The glass g is brittle (disposed to shatter if struck) in virtue of having the chemical composition it does.

-

The Parthenon is colored because it is white.

-

The desk d in front of me exists due to the arrangement of its parts a1-an.

Friends of grounding universally take it to be closely connected with metaphysical (or non-causal) explanation, either by being identical to metaphysical explanation or by being the worldly relation that backs successful metaphysical explanations (analogous to the way the causal relation is thought by many causal realists to be the worldly relation that backs successful causal explanations). For the purposes of this article, nothing hinges on the question of whether grounding is or merely backs metaphysical explanation, so I will not be terribly careful about that distinction. Furthermore, I will treat grounding as a relation between facts, where facts are complex structured entities, built out of e.g. objects, properties and relations, logical items, and sometimes even further facts.Footnote 1 (I will employ the common convention of using square brackets to form names of facts. Thus e.g. “[Caesar is emperor]” names Caesar’s being emperor.) On this treatment, the connection between grounding and explanation comes out such that when some facts [P1], … [Pn] fully ground another fact [Q], [Q] obtains (fully) because [P1], … [Pn] jointly obtain.Footnote 2

So much for grounding, for now. What is reductionism about grounding? I take a reduction of grounding to be a (purported) explanatory account of what grounding consists in. There are slightly different ways this could be interpreted. One might think of it as revealing the metaphysical analysis of a relation into further component relations and/or properties, structured in a certain way.Footnote 3 Or one might think of it as a matter of uncovering the essence of a relation – the identity or the real definition of what it is to be that relation (Fine, 1994). The details will not matter for our current purposes. What does matter is that on any such conception of reduction, a reductive account of grounding is distinct in kind from a conceptual analysis of grounding. It seems highly likely that there is no informative analysis of our concept of grounding into simpler, more basic concepts from which it is defined. But this is compatible with there being something more fundamental which grounding – the phenomenon picked out by our concept – consists in. (Compare e.g. with how a given color concept might not be conceptually analyzable, even though the property expressed by that concept reduces to certain physical properties.) With these preliminaries out of the way, it is time to move on.

3 Opaque Grounding

In this section, I will introduce the kind of opaque grounding cases that make trouble for the proposed reductions of grounding available. Although I will not be attempting to provide an explicit definition of the notion, I will outline the central features that characterize cases of opaque grounding.Footnote 4 To this end, I will be considering a traditional form of moral non-naturalism. Some qualifications are, however, in order. Firstly, although moral non-naturalists typically also espouse some characteristic views in moral semantics and moral epistemology, I will here focus exclusively on the metaphysical commitments of the view. Secondly, some of the central concepts used in the contemporary metaphysics literature (including in the discussion over grounding reductionism) – such as e.g. grounding, essence, building, and fundamentality – were either not in common usage or at least not as salient when some of the most important non-naturalist accounts were formulated. For example, while G. E. Moore often talks of part/whole relations, we are unlikely to find him speaking of building relations in general. After all, Moore made his most significant contributions before even the great 20th century breakthroughs in the study of modality, and considerably ahead of the hyperintensional turn that metaphysics is currently undergoing. But this is not to say that Moore’s work is irrelevant to issues formulated in terms of the tools we now employ, or that the ideas he was trying to capture are not amenable to elaboration with the help of those tools (perhaps even to some theoretical benefit). Some of my characterization of non-naturalism will thus take the form of a partial reconstruction of what a non-naturalist should say, given (i) their typical commitments and theoretical goals, and (ii) the metaphysical machinery we now have at our disposal to formulate theses and capture said commitments.

With these clarifications out of the way, let us start by considering the central commitments of non-naturalism. Moral non-naturalism entails metaphysical realism about moral phenomena (such as moral properties, relations, and facts) – i.e. the view that those phenomena exist and that their existence, instantiation, and (for facts) obtaining is a constitutively mind-independent matter. This is a view shared by moral naturalists, who hold that moral phenomena are simply part of the mind-independent natural world. Non-naturalism, however, includes a commitment to the deep metaphysical separation of the natural and the moral domains. Thus, in providing a basic characterization of non-naturalism, Pekka Väyrynen writes:

The distinctive claim of non-naturalist moral realism is that these moral properties, and perhaps normative properties in general, are sui generis – significantly different in kind from any other properties. […] To spell this out a bit, the non-naturalist thinks that at least some normative properties aren’t identical to any natural or supernatural properties, nor do they have a real definition, metaphysical reduction, or any other such tight metaphysical explanation wholly in terms of natural or supernatural properties. Normative properties are, in short, discontinuous with natural and supernatural properties. (Väyrynen, 2018: 171)Footnote 5

For simplicity, let us focus in the first instance on non-naturalism as a view which takes moral properties, relations, and facts to be non-natural, setting issues of normativity more broadly to the side. The kind of non-naturalism we are here concerned with holds that any pure moral property or relation M must satisfy certain conditions. (By speaking of pure moral properties and relations, I intend to exclude e.g. conjunct properties built out of both moral and natural conjunct properties, such as being virtuous and over 6 feet tall, as well as properties picked out by thick moral concepts, such as being courageous. There may be further types of properties and relations that should be excluded from the scope of the conditions. It seems that a moral non-naturalist can accept that such impure moral properties and relations are exceptions to the strict metaphysical separation of the moral and the natural without compromising the core of their view, as long as they take the central pure moral properties and relations to satisfy the conditions to be outlined here. In the following, I will often leave this qualification implicit.)Footnote 6 The first condition the non-naturalist takes any pure moral property or relation M to satisfy is fairly straightforward:

Distinctness: M is numerically distinct from every natural property/relation.

Väyrynen furthermore attributes to non-naturalists the idea that some moral properties and relations lack a reduction or other tight metaphysical explanation in terms of natural properties (or relations). The motivating impulse behind this idea is that moral properties and relations have some normative feature – e.g. their having a special kind of authority over agents, or their providing categorical reasons for action, or that they involve objectively binding standards for conduct – which no natural property or relation could possibly possess.Footnote 7 Consequently, non-naturalists think that moral properties and relations cannot be reduced to or otherwise built out of any natural components, since any such combination of components would fail to exhibit the relevant normative features.Footnote 8 In this vein, Stephanie Leary writes

[N]ormative properties would be of the same kind as paradigm non-normative properties if they were ultimately “built up” out of such properties. But if a normative property is not ultimately built up out of such properties, then it’s something “over and above” all other properties. And since paradigm non-normative properties include scientific ones, this implies that there is some feature of reality that is not ultimately built up out of scientific features. [This characterization of moral non-naturalism] thus speaks to and elucidates the non-naturalist’s pre-theoretical claims that normative properties are sui generis and incompatible with a purely scientific worldview […]. (Leary, 2022: 805)

I propose to capture this commitment (applied to an arbitrary pure moral property or relation M) with the help of the following thesis:

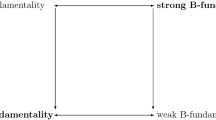

Fundamentality: M is either absolutely fundamental, or any property or relation F such that M is reducible to or otherwise built out of F is a non-natural moral property or relation.

I take on board the recently popular idea that facts about relative fundamentality (and, in turn, the distribution of absolute fundamentality) derive from patterns of building or construction relations, such as e.g. set formation, composition, constitution, and fact-grounding (Bennett, 2017). (I will have more to say about building in Sect. 4.1 below). Since non-naturalists think that moral relations and properties cannot be reduced to or built out of natural phenomena, the basic moral relations and properties must on their view be as fundamental as the most fundamental natural properties and relations. Fundamentality is, however, compatible with the view that although moral phenomena are in this way not reducible to or constructed out of any natural phenomena, there is metaphysical structure within the moral domain. A non-naturalist might think e.g. that moral rightness reduces to moral value or that all the other moral properties and relations are ultimately built out of the moral reason relation, which is itself unbuilt. In the first case, moral rightness would not be an absolutely fundamental property; in the second case, the reason relation would be the only absolutely fundamental moral property or relation.

Another important commitment which showed up in Väyrynen’s characterization of non-naturalism above concerns the essences of moral properties and relations. For a moral non-naturalist will hold that the discontinuity between the moral and the natural is reflected also in what it is to be certain moral properties and relations, the identity of those properties and relations, as captured by the relevant real definitions. It would not make much sense to insist on the fundamental metaphysical discontinuity between the natural and the moral and then go on to hold that it is possible to give an exhaustive account of what it is to be, say, moral rightness or the reason relation in terms of natural properties and relations.Footnote 9 Unfortunately, spelling out the exact details of this is difficult. It is tempting to think, at a first glance, that a non-naturalist account should simply ban any natural property or relation from figuring in the essence of the relevant pure moral property or relation M. But it has been pointed out that even a strict non-naturalist may accept that some natural properties or relations can figure in the essence of a moral property or relation that lacks a tight metaphysical explanation in terms of anything natural (Leary, 2017: 96). For even a non-naturalist might think that it is part of what it is to be moral rightness to be a property of actions, or to be self-identical (both of these presumably being natural properties). It is hard to say anything perfectly general about which kinds of natural properties and relations can acceptably occur in the essence of a pure moral property or relation without violating the spirit of moral non-naturalism. To be able to make at least some progress, it will help to take a temporary detour over another aspect of non-naturalism.

All three of the commitments thus far discussed capture some aspect of the metaphysical discontinuity or separation that non-naturalists believe characterizes the relationship between the natural world and at least the core part of the moral domain. Despite this belief, most non-naturalists (like most philosophers generally) still accept the supervenience of the moral upon the natural, i.e. that there can be no moral difference without some natural difference. But they do not stop at this merely modal thesis – and, in fact, doing so would be puzzling in the extreme. Suppose a non-naturalist accepts hedonistic utilitarianism in normative ethics. They will then hold that moral rightness in actions supervenes on happiness-maximization – there can be no difference with respect to moral rightness without a corresponding difference with respect to happiness-maximization. But surely they will not think that this mere pattern of modal covariation exhausts what there is to be said about the metaphysical relations between an action’s maximizing happiness and its being morally right. For they will additionally think that a token action’s a being morally right is due to its maximizing happiness; that a is morally right in virtue of its being happiness-maximizing; that a’s maximizing happiness makes it morally right. Mere supervenience does not suffice to license such explanatory talk. This is especially clear in the case of the hedonistic utilitarian, since she will hold that being happiness-maximizing and being morally right are necessarily co-extensive. On this account, happiness-maximization supervenes on moral rightness just as much as moral rightness supervenes on happiness-maximization – there can be no difference with respect to moral rightness without a corresponding difference with respect to happiness-maximization, but equally there can be no difference with respect to happiness-maximization without a corresponding difference with respect to moral rightness. Nevertheless, the explanatory connection runs only in one direction: from the fact that a token action a is happiness-maximizing to the fact that a is morally right.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the explanatory claims made here are not causal: it’s not that the action a is first happiness-maximizing at t1, and then only at some later time t2 comes to be morally right. Rather, according to the hedonistic utilitarian non-naturalist, the action’s being morally right is non-causally or metaphysically explained by its being happiness-maximizing. For all the metaphysical discontinuity they ascribe to the relationship between the natural and the moral, non-naturalists thus still think particular moral facts are grounded in natural facts. Moral non-naturalists are consequently committed to any pure moral property or relation M satisfying the following condition in addition to Distinctness and Fundamentality:

Groundedness: Necessarily, for any fact f of the form [M(x1…xn)], there are some facts [N1] … [Nm] such that each of [N1] … [Nm] is a natural fact, and [N1] … [Nm] jointly ground f.

This formulation of Groundedness leaves it open whether the relevant natural facts fully ground the moral fact in question. Since the accounts of grounding I will be investigating are all accounts of full grounding, I will initially be working under the simplifying assumption that the moral non-naturalist takes the moral facts in question to be fully grounded by natural facts. In Sect. 5 below, I will address how the question of reductionism is affected if the moral non-naturalist is interpreted as taking moral facts to be merely partially grounded in natural facts.

The Groundedness commitment seems to have been present even in early incarnations of non-naturalism in analytic philosophy. In an exchange, C. D. Broad asks for clarification on Moore’s conception of the relationship between the moral and non-moral properties of an object:

I am inclined to think that the fact which Moore has in mind here is that goodness, in the primary sense, is always dependent on the presence of certain non-ethical characteristics which I should call “good-making.” If an experience is good (or if it is bad), this is never an ultimate fact. It is always reasonable to ask: “What makes it good?” or ”What makes it bad?” as the case may be. And the sort of answer that we should expect to get is that it is made good by its pleasantness, or by the fact that it is a sorrowfully toned awareness of another’s distress, or by some other such non-ethical characteristic of it. We might, therefore, distinguish the characteristics of a thing into the following two classes, viz., ultimate and derivative. Goodness would certainly fall into the class of derivative characteristics. (Broad, 1942: 60)Footnote 11

To this, Moore replies:

It is true, indeed, that I should never have thought of suggesting that goodness was “non-natural,” unless I had supposed that it was “derivative” in the sense that, whenever a thing is good (in the sense in question) its goodness (in Mr. Broad’s words) “depends on the presence of certain non-ethical characteristics” possessed by the thing in question: I have always supposed that it did so “depend,” in the sense that, if a thing is good (in my sense), then that it is so follows from the fact that it possesses certain natural intrinsic properties, which are such that from the fact that it is good it does not follow conversely that it has those properties. (Moore, 1942: 588)

In light of Moore’s commitment to the indefinability of “good”, he cannot be taken to intend anything like logical or analytical entailment by “follows from”. The asymmetrical relation of depending on or following from at stake here is plausibly (the converse of) grounding.Footnote 12

Having formulated Groundedness, I can now go back to propose the following non-naturalist constraint on the essence of any pure moral property or relation M:

Essential Isolation: For any natural facts [N1] … [Nm] such that [N1] … [Nm] jointly ground a fact of the form [M(x1…xn)], there is no natural property or relation F such that (i) F is instantiated in at least one of [N1] … [Nm], and (ii) F is part of the essence of M.

If a natural property or relation F is instantiated in the grounds of a moral fact of the relevant kind, Essential Isolation blocks F from being part of the essence of the property or relation M instantiated in the moral fact.Footnote 13 Arguably, further constraints are needed to fully capture everything a non-naturalist would want to say about the essences of moral properties and relations – the non-naturalist would plausibly want further natural properties and relations to be blocked from the essence of M beyond just those figuring in the grounds of instantiations of M. But Essential Isolation at least avoids the problems mentioned above, while capturing the core non-naturalist idea that identifying the natural conditions in virtue of which things are morally right, valuable (and so on) does not amount to uncovering what it is to be right or valuable. And it is this idea that is important in opaque grounding cases. Support for something like Essential Isolation is voiced by Gideon Rosen, who characterizes the difference between naturalist and non-naturalist realists in ethics in the following way:

Ethical naturalism is not the view that the normative supervenes on the non-normative. G. E. Moore and his twenty-first-century followers, including Parfit […] and Scanlon, all accept Supervenience, but they are not ethical naturalists just for that. The nonnaturalist’s distinctive claim is that even if there are true propositions that specify naturalistic necessary and sufficient conditions for each moral feature – as there must be given Supervenience if we allow infinitary conditions – these principles do not tell us what it is for an action to be, say, right. They are rather metaphysically synthetic laws that connect a normative feature, moral rightness, with utterly distinct nonnormative features, the so-called “right-making” features. The naturalist’s distinctive claim must therefore be that not only do such principles exist: they tell us what it is for an action to be right. (Rosen, 2020: 212)Footnote 14

According to the hedonistic utilitarian, an action’s being morally right must be grounded in its maximizing happiness. Maximizing happiness is thus a sufficient condition for being morally right. But if our hedonistic utilitarian is a moral non-naturalist, she will insist that the essence of moral rightness does not involve this sufficient condition in any way. To borrow a metaphor used by Fine (2012: 75) in a different case, the essence of moral rightness (according to the non-naturalist’s view) knows nothing of happiness-maximization.

With these conditions in place, let us take a step back and illustrate their combination. Suppose you subscribed to classical hedonistic utilitarianism in normative ethics and non-naturalism in metaethics. You would then think that what makes any specific action morally right is its maximizing happiness, i.e. you would take (for a token action a) [a maximizes happiness] to ground [a is morally right] – [a is morally right] obtains because [a maximizes happiness] obtains, and not the other way around (that’s an instance of Groundedness). At the same time, you would hold that the property of being morally right is numerically distinct from every natural property and relation – including the property of maximizing happiness (i.e. you would accept an instance of Distinctness). Furthermore, since you would rule out moral rightness being reducible to or built out of any natural property (including the property of maximizing happiness), you’d take it to either be an absolutely fundamental property in its own right, or at most constructed out of other non-natural moral properties and relations (such as the moral reason relation). That’s Fundamentality. Finally, while you might accept that the essence of moral rightness involves some fairly mundane natural properties (such as that of being a property of actions), you would deny that the property of maximizing happiness plays any part in what it is to be morally right. Though the property of maximizing happiness is instantiated in the ground of the fact [a is morally right], the non-naturalist would think that moral rightness lacks a real definition in terms of that property. That’s Essential Isolation.

This kind of moral non-naturalism is a paradigm case of a theory that is committed to what I call opaque grounding. If the theory is correct, we are here dealing with a situation where facts of a certain kind (moral facts) are grounded in facts of a different kind (natural facts), yet there are no relations of reduction, building, or essential involvement relating the properties or relations instantiated in the grounded fact to the properties or relations instantiated in the grounds. In a metaphor: even if God had perfect and complete knowledge of everything the properties of being morally right and of maximizing happiness consisted in – their essences, what they reduced to, and how they were metaphysically constructed – she would not thereby be able to predict that the fact [a maximizes happiness] grounds [a is morally right]. In a sense, the grounding connection in such cases is less intimate than in a typical, “transparent” case of grounding.

While I have now explored moral non-naturalism at length in order to be able to outline what characterizes cases of opaque grounding, I do not think it is the only view that plausibly fits this pattern. In the first instance, the same treatment is easily extended to analogous non-naturalist views about other kinds of normativity. An aesthetic non-naturalist may e.g. take beauty to be a sui generis, irreducible property lacking a real definition or reduction in terms of natural properties but still think that instantiations of that property must be grounded in instantiations of certain natural properties. But there is no reason to think that the patterns at work here need only be applicable within the metaphysics of normativity. The notion of opaque grounding could e.g. be employed in the philosophy of mind to articulate a certain kind of property dualism. For on the one hand, there is some undeniable appeal to the idea that phenomenal properties and any material properties (such as neurological or functional properties) have fundamentally different and discontinuous natures. At the same time, it is highly implausible to think that my current phenomenal state is metaphysically independent of my material state, and one might wish to deny the possibility of so-called zombie worlds, where creatures materially indiscernible from us exist without any phenomenal activity whatsoever. But equipped with a notion of opaque grounding, a property dualist can take phenomenal properties to necessarily be instantiated in virtue of instantiations of material properties, while simultaneously taking their natures to be so radically different that no phenomenal property is reducible to, built out of, or has a real definition in terms of any material property. Such a view could constitute a potentially interesting alternative to both physicalism and a more radical Cartesian substance dualism.Footnote 15

From these examples, one might get the impression that opaque grounding can only ever be at stake when we’re dealing with the spooky metaphysics of the non-natural or the immaterial. But I do not think that is right. Very roughly put, the core of the idea of opaque grounding is grounding without reducibility, but that idea does not in and of itself come with any anti-naturalist or anti-physicalist bias. Plausibly, even if metaphysical naturalism and/or physicalism is true, some natural phenomena are reducible to and built out of others, while some are irreducible and bedrock. For a possible example of a naturalist opaque grounding view, consider a kind of non-reductive moral naturalism. One might e.g. think that even though moral properties and relations (or some subset thereof) are not reducible to or built out of any other natural properties, they are perfectly respectable natural properties in their own right by virtue of possessing some characteristic feature of the natural (such as e.g. bestowing certain causal powers on their bearers). Just like the non-naturalist, the naturalist could take [a is morally right] to be grounded in e.g. [a maximizes happiness] without taking the property of being morally right to be built out of, reducible to, or to have a real definition in terms of, the property of maximizing happiness. On this naturalist view, moral rightness could still be part of the patterns of the natural world, perhaps causally tending to the stability and frequency of certain forms of social arrangements as compared to others, and there might be a more straightforward story to tell about how we come to know that property (and facts involving it) than on a non-naturalist theory.Footnote 16 While there is obviously much more work to be done to assess the ultimate viability of such a view, the sketch here provided goes some way towards illustrating that there is no necessary connection between opaque grounding and what some would consider ‘spooky’ metaphysics.Footnote 17 With this out of the way, it is time to move on to consider how opaque grounding spells trouble for reductionism about grounding.

4 Reductionism about Grounding

In this section, I will go through four representative hyperintensionalist reductions of grounding that have been offered in the literature and demonstrate that they cannot accommodate the possibility of opaque grounding cases. Conveniently, these accounts divide into two groups: building-based accounts and essence-based accounts.

4.1 Building-based Reductionism

Recently, the notion of a building relation has attracted a great deal of attention in metaphysics. As a first characterization, building relations (or construction relations) are those relations whereby more fundamental entities give rise to or generate less fundamental entities. Common examples of building relations are composition, constitution, set formation, and realization. The current wave of interest in building relations as a family, as well as the terminology of “building”, originates in the work of Karen Bennett.Footnote 18 Once the notion of a building relation is on the table, the issue of whether building and grounding are connected becomes salient. One attractive option would be to reduce one of the phenomena to the other – and this idea has indeed been explored in the grounding literature. (Bennett herself includes the relation of fact grounding among the building relations. On such a treatment, the issue at stake here is whether grounding and the other building relations are connected in any interesting way, e.g. by grounding reducing to the other relations. But for convenience, I will in this section be talking as if grounding is antecedently excluded from the list of building relations. When I henceforth talk of building relations, I should thus be understood as talking about the class of building relations except grounding.)

Cases of opaque grounding, however, constitute a general problem for building-based accounts of grounding. Given Fundamentality, opaque grounding cases will amount to the grounding of facts involving properties and relations which are either absolutely fundamental – and thus not metaphysically built at all – or built out of properties and relations which are not involved in the ground(s) of the fact. To return to the previous example: a moral non-naturalist might hold that [a maximizes happiness] grounds [a is morally right] even though the property of being morally right is either absolutely fundamental, or only reducible to or built out of other moral properties. On that view, there will be no building relations holding between constituents of the ground (which are entirely natural) and the grounded fact available to serve as a reduction base. Nor will there, as we will see, plausibly be any building relations holding directly between the ground and the grounded fact themselves.

The most worked out building-based account of grounding available in the literature is due to Wilsch (2015; 2016). Wilsch articulates and defends a deductive-nomological account of grounding, on which grounding consists in determination in accordance with metaphysical laws. This account is then combined with a specific model of how metaphysical laws work: the constructional conception of metaphysical laws. Wilsch takes the deductive-nomological account of grounding to be in principle independent of any specific conception of the content of metaphysical laws. But for our current purposes, I will treat the account as a package deal, and only later consider what decoupling the constructional conception from the deductive-nomological account might entail.

As the name suggests, the constructional conception of metaphysical laws treats the metaphysical laws as principles governing the behavior of building relations, relations whereby “the constructing entities are more basic than the constructed entity, and the constructed entities exist in virtue of the constructing entities.” (Wilsch, 2015: 3300) According to the constructional conception, there are two different kinds of metaphysical laws, each of which plays a different role. Ontological principles regulate the conditions entities must satisfy in order to generate a further entity via a particular building relation. Thus, suppose the organicist theory of composition is correct. There is then an ontological principle for composition determining that for any plurality xx, if the activities of the xx constitute a life, there is an entity y which is composed out of the xx. Suppose a1-an are all the parts of Bo the badger. [Bo exists]’s being determined by [The activities of a1-an constitute a life] together with the ontological principle for composition then explains why [The activities of a1-an constitute a life] grounds [Bo exists]. Wilsch calls the way a less fundamental entity is derived from more fundamental entities via an ontological principle its “constructional history”. Principles belonging to the other kind of metaphysical law, linking principles, determine facts about which properties built entities instantiate based on (i) the constructional histories of those entities and properties, together with (ii) facts about their constructors. Thus, for a simple (and somewhat idealized) example, consider constitution. There is a linking principle for constitution determining that for any objects x and y and properties X, if x was constructed out of y via the constitution relation, and y instantiates X, then x instantiates X.Footnote 19 So since [Goliath weighs 2 kg] is determined by [Lumpl constitutes Goliath] and [Lumpl weighs 2 kg] together with the linking principle for constitution, [Lumpl constitutes Goliath] and [Lumpl weighs 2 kg] jointly fully ground [Goliath weighs 2 kg].

There is much about Wilsch’s sophisticated discussion of building relations and metaphysical laws that I have had to simplify or ignore here in the interest of brevity. But I hope to have sketched the background needed for the reader to grasp the following statement of Wilsch’s account of grounding, which I call “Building I”:

Building I:

[P1] … [Pn] fully ground [Q] if, and only if:

- (i)

[P1] obtains and … [Pn] obtains;

- (ii)

[Q] is determined by [P1] … [Pn] in accordance with an ontological principle or a linking principle.

(For convenience, I have formulated Building I as a biconditional. But it should be read as a reductive account of what grounding consists in, as outlined in Sect. 2 above. The same will be the case for all the accounts I will be discussing in the following.) I have above sketched some examples of grounding which Building I handles comfortably. But it cannot deal with cases of opaque grounding. Consider again our moral non-naturalist and suppose for simplicity that she is a classical hedonistic utilitarian. She thus takes [a maximizes happiness] to fully ground [a is morally right] (where a is a token action). This is not a matter of determination in accordance with an ontological principle. Ontological principles regulate the conditions under which any xxs give rise to another entity via a particular building relation (such as composition or constitution) and can therefore only be involved when the grounded fact is an existence fact. However, treating the case as an example of determination in accordance with a linking principle is no more plausible. Linking principles play the role of regulating which entities instantiate which properties (or relations) on the basis of the constructional histories of those entities and properties. But since the non-naturalist is committed to Fundamentality as outlined in Sect. 3, she will hold either that moral rightness lacks a constructional history (since it is absolutely fundamental), or that the only properties and relations that figure in its constructional history are other non-natural moral properties and relations (since it is built exclusively out of such properties and relations). And neither entity involved in the ground in the case at hand (the token action a and the property of maximizing happiness) is a non-natural moral property or relation according to the non-naturalist view at hand. So [a maximizes happiness]’s opaquely grounding [a is morally right] cannot be treated as involving determination in accordance with a linking principle either. (I relegate a complication to a footnote.)Footnote 20 Since Building I entails that every case of grounding involves determination in accordance with either an ontological principle or a linking principle, it follows that the account fails to handle opaque grounding cases.

Another complication needs to be mentioned. Building I combines two views which Wilsch takes to be in principle separable: the deductive-nomological account of grounding and the constructional conception of metaphysical laws. Since the arguments above hinged on the fact that our non-naturalist takes moral rightness to be unbuilt (or at least not built out of any natural properties or relations), one might hold out hope for some other conception of the content of metaphysical laws such that the combination of that conception and the deductive-nomological account of grounding handles cases of opaque grounding successfully. Although we should not rule out that possibility, I would also like to point out that Wilsch seems to me to underestimate the work that the constructional conception does for the viability of the deductive-nomological account. For there seems to be nothing in the general idea that grounding is determination in accordance with metaphysical laws that guarantees e.g. that if we start from a given fact [P] and input it into some metaphysical laws, we will never have those laws output [P] itself, or output some [Q] which could then in turn be input into metaphysical laws to output [P] again. (The first case would be a violation of the irreflexivity of grounding, and the second one a violation of the asymmetry of grounding.) The component of Wilsch’s approach that excludes this is instead the assumption that the relevant metaphysical laws all concern building relations, since building relations are partially characterized by their generating less basic entities out of more basic entities. Not just any conception of the content of metaphysical laws will be able to combine with the deductive-nomological approach to achieve that. Thus, I think the issue of whether there is some other plausible conception of metaphysical laws which will allow Wilsch’s deductive-nomological account to handle opaque grounding cases is just a special case of the question of how widely the problem generalizes across other possible reductive accounts of grounding. I will discuss that question in Sect. 5.

Wilsch is not the only philosopher to consider an account of grounding in terms of building relations. Jessica Wilson is a self-professed skeptic about grounding whose central criticism is that generic grounding claims (“Big-G Grounding” claims) add nothing illuminating to claims about more specific relations of what Wilson calls “metaphysical dependence” or “small-g grounding”, by which she seems to have in mind something like what I’ve above called “building relations.” (Wilson, 2014) But regardless of Wilson’s own intentions, one might take her idea as material for a reduction of grounding rather than an elimination. Kris McDaniel has expressed sympathy for the basic thrust of Wilson’s view but uses it to inform his own reductive approach to grounding instead, employing additionally a notion of one thing having a greater degree of being or being more real than another. McDaniel describes his recipe for reducing grounding as follows:

First, do first order metaphysics in order to get an inventory of the various connective relations between facts that are needed for a complete theory. Perhaps this inventory of connective relations will include the relation of entailment (in play when one fact obtains in all the worlds in which another fact obtains), constitution (in play when the existence of a lump of matter constitutes the existence of a statue or a moral fact is constituted by a physical fact), determination (in play when the fact that something is scarlet determines the fact that something is red), disjunction (in play when two facts form their disjunction), and many others. We won’t know what they are independently of doing first-order metaphysics. […] Provided that we have arrived at a suitable list of connecting relations between facts, we could identify grounding (the phenomenon!) with the transitive closure of the disjunction of the conjunctions of connecting relations plus being more real than. (McDaniel, 2017: 239)

We thus get something like the following recursive account:

Building II:

[P1] … [Pn] fully ground [Q] if, and only if:

There is some relation R and some facts [S1] … [Sn] such that.

- (i)

R is a building relation.

- (ii)

[S1] … [Sn] stand in R to [Q].

- (iii)

[S1] … [Sn] are more real than [Q].

- (iv)

each of [S1] … [Sn] is either identical to one of, or fully grounded by, [P1] … [Pn].

McDaniel’s account differs from Wilsch’s in accounting for grounding between facts in terms of building relations between those facts themselves, rather than between their constituents. Both clauses (ii) and (iii), however, seem to render Building II potentially vulnerable to independent lines of objection based on opaque grounding cases. Let us start with (ii). Since McDaniel’s list of “connective relations” is intentionally preliminary and incomplete in anticipation of the complete theory of first order metaphysics, it is a little difficult to say with any firm degree of conviction whether each case of grounding will be associated with some plausible building relation. But McDaniel’s list does not immediately inspire confidence. For one thing, entailment as characterized by McDaniel, being a merely modal relation, does not obviously seem relevant to matters of metaphysical dependence or building. As for the other example relations provided, none of them seem applicable to opaque grounding cases. To begin with the simplest case (and sticking with moral non-naturalism and classical hedonistic utilitarianism as our illustrating theories), [a is morally right] is obviously not the disjunction of [a maximizes happiness], or even the disjunction of that fact and some other natural fact. Nor is it consistent with non-naturalist commitments to take [a maximizes happiness] to stand in a determinate/determinable relationship to [a is morally right]. Determinates stand in specificational relationships to their determinables: e.g., being scarlet is a more specific way of being red (Wilson, 2017). But the non-naturalist cannot accept that a’s maximizing happiness is a more specific way for a to be morally right. If it were, then surely [a maximizes happiness] would be a moral fact, since [a is morally right] is and the former would specify the latter. But it seems implausible on the face of it that [a maximizes happiness] is itself a moral fact – and, at any rate, a moral non-naturalist is particularly unlikely to accept that view. Despite McDaniel actually using the relation between a physical fact and a moral fact as an example of constitution, I think that relation too is unsuited to provide a building-based diagnosis of opaque grounding cases. McDaniel’s two examples of constitution are importantly different. The relation between the lump of clay and the statue is one of material constitution, which earns its status as a building relation (or, in Wilson’s terms, a ‘small-g grounding relation’ or ‘relation of metaphysical dependence’) partially by being (in a metaphor) ‘thicker’ than a mere (‘Big-G’) grounding connection. For example, when the lump materially constitutes the statue, it does not just follow that the statue exists in virtue of the existence and configuration of the lump, but also that the lump and the statue are spatially co-located, that a wide range of properties and relations instantiated by the lump are also instantiated by the statue, and so on. But insofar as a moral non-naturalist can say that e.g. [a maximizes happiness] ‘constitutes’ [a is morally right], there does not seem to be any ‘thicker’ relation attributed than that of [a is morally right]’s simply obtaining in virtue of [a maximizes happiness] – and that’s just the grounding relation. The non-naturalist’s view of the relation between [a maximizes happiness] and [a is morally right] is thus not plausibly diagnosable as involving constitution in any sense needed to satisfy Building II. Although a proponent of Building II could go on to attempt to identify other building (or ‘connective’) relations more plausibly involved in opaque grounding cases, I can only report (for whatever it’s worth) that I have yet to encounter any viable candidate relations in the building literature.Footnote 21

Moving on from this somewhat tentative discussion of (ii), clause (iii) of Building II seems just as unlikely to be satisfied in opaque grounding cases. Admittedly, the kind of views I discussed in Sect. 3 above have typically not been combined with any claims about degrees of being or degrees of reality. But once we introduce that kind of ideology, it seems that the non-reductive character of the views will push their proponents away from accepting the relevant instances of (iii). For example, insofar as a moral non-naturalist recognizes a distinctive notion of degrees of reality, the basic intuitions motivating her view would seem to make it natural to hold that the moral is at least no less real than the natural, and perhaps even that it has a greater degree of reality than many parts of the natural world. Consequently, she will hold that e.g. [a maximizes happiness] grounds [a is morally right] without being any more real than the moral fact. Thus, (iii) provides another illustration of why Building II is ill-equipped to handle opaque grounding cases.

4.2 Essence-based Reductionism

We have seen that building-based reductive accounts fail to accommodate opaque grounding cases. Another prime facie appealing reductive approach is to try to account for grounding in terms of essence. Something’s being essential to a certain entity, on this approach, is not to be thought of as its being merely metaphysically necessary for the existence of that entity. Rather, it’s a matter of being part of what it is to be that entity, part of its identity or real definition. It is metaphysically necessary for my existence that 2 + 2 = 4 (since it’s metaphysically necessary simpliciter that 2 + 2 = 4), but it is not part of my identity, what it is to be me, that 2 + 2 = 4.

However, essence-based accounts of grounding too will struggle to accommodate cases of opaque grounding. The reason is that such cases satisfy instances of the Essential Isolation commitment outlined in Sect. 3. Thus, the moral non-naturalist might e.g. hold that [a maximizes happiness] fully grounds [a is morally right]. Yet at the same time, by Essential Isolation, she will deny that the property of maximizing happiness is involved in the essence of moral rightness. And even though that commitment is formulated in the first instance as a thesis about the essences of moral properties and relations, it plausibly entails an analogous commitment at the level of facts as well. If maximizing happiness is not even part of what it is to be the property of being morally right, then what it is to be the fact [a is morally right] will not involve the fact [a maximizes happiness] either. After all, a fact of this form just is the instantiation of a property by a particular token action. So any essence-based account of grounding that requires the essence of a grounded fact to involve the ground will be incompatible with cases of opaque grounding.

One essence-based reductive account of grounding, which I will call “Essence I”, is provided by Fabrice Correia:

Essence I:

[P1] … [Pn] fully ground [Q] if, and only if:

- (i)

[P1] obtains and … [Pn] obtains;

- (ii)

it is part of the essence of [Q] that: if [P1] obtains and … [Pn] obtains, then [Q] obtains.Footnote 22

Essence I works well for many standard cases of grounding. For example, friends of grounding typically hold that [Caesar exists] grounds [{Caesar} exists]. And it is plausible that it is part of the essence of [{Caesar} exists] that if [Caesar exists] obtains, so does [{Caesar} exists]. For it is plausibly part of what it is to be the singleton set {Caesar} to exist if its member, Caesar, does – and this then transfers over to the essence of the relevant existence fact. Similarly, many think that [The Parthenon is white] grounds [The Parthenon is colored]. It is plausible that it is part of what it is to be the determinable of being colored that anything which instantiates the determinate white also instantiates it. Correspondingly, it is equally plausible that part of what it is to be the fact [The Parthenon is colored] is to obtain if [The Parthenon is white] obtains. So this case too is compatible with Essence I.

However, for the reason outlined above, Essence I is straightforwardly unable to handle cases of opaque grounding. Essence I requires any ground to be involved in the essence of what it grounds. The Essential Isolation condition on opaque grounding precludes exactly such involvement. But Zylstra (2019) has developed an account of grounding in terms of essence that avoids the aforementioned problem for Essence I by not requiring any direct involvement of the ground in the essence of the grounded fact. Zylstra starts from the following essentialist notion of generic existential dependence (where “x” is a singular variable, “X” a plural variable, and “R” ranges over relations):

x is existentially dependent = df. There is some R such that it is essential to x that x exists only if (there are Xs such that x stands in R to the Xs and the Xs exist.)Footnote 23

This defines a notion according to which an entity can be dependent without requiring any specific entity for its existence. Thus, consider the property of being a philosopher under an “Aristotelian” conception of universals, on which only instantiated universals exist. On such a conception, the property of being a philosopher is existentially dependent in the sense defined above, since (let us suppose) it is essential to the property that it exists only if (i) there is some plurality of Xs which the property is related to by the relation of being instantiated by, and (ii) the Xs exist. This notion of existential dependence then forms the basis for Zylstra’s account, which I present here as Essence II:

Essence II:

The facts G fully ground [Q] if, and only if:

There is some R such that.

- (i)

it is essential to [Q] that [Q] exists only if (there are Fs such that [Q] stands in R to the Fs and the Fs exist);

- (ii)

[Q] stands in R to the Gs and the Gs exist.Footnote 24

According to this account, grounding consists in (1) a fact [Q]’s being existentially dependent on there being some Fs standing in some appropriate relation R to it, together with (2) the Gs in fact existing and standing in R to [Q] (thus actually satisfying the condition set up by [Q]’s being existentially dependent). Allow me to illustrate the account by instantiating it. It is a popular idea that instantiations of determinate properties ground instantiations of determinable properties. So, for example, [The Parthenon is white] grounds [The Parthenon is colored]. Essence II handles this case well. For there is a relation – the relation holding between the instantiation of a determinable and the instantiation of any of its determinates, call it D – such that (i) it is essential to [The Parthenon is colored] that it exists only if there is some existing plurality of facts F to which [The Parthenon is colored] is related by D, and (ii) [The Parthenon is colored] stands in D to the existing fact [The Parthenon is white].

Essence II is not subject to the same objection from opaque grounding that I raised against Essence I. For suppose [a maximizes happiness] grounds [a is morally right], as a non-naturalist embracing classical hedonistic utilitarianism would have it. This does not, according to Essence II, entail that the essence of the moral fact involves the natural fact [a maximizes happiness]. As far as essences are concerned, it only entails that the essence of the moral fact involves a generic condition on the existence of the fact, a condition which does not involve any specific natural fact.

However, a distinct problem arises for Essence II in accommodating cases of opaque grounding. For the account entails that whenever [P] grounds [Q], there is a relation R such that (i) it is essential to [Q] to exist only if it stands in R to something, and (ii) [Q] actually stands in R to [P]. The problem now is that in opaque grounding cases, there does not seem to be any suitable relation available to do the job required. In many of the cases Zylstra uses to illustrate Essence II, the salient relation is a building relation (or a relation suitably connected to a building relation). Thus, in the case of [Caesar exists] grounding [{Caesar} exists], it is plausible that it lies in the essence of the latter fact to only exist if it stands in S to some fact – where S is the relation that holds between two facts when the second is the existence fact for the set formed solely out of a given entity and the first is the existence fact for the element in question. And in the case of [The Parthenon is white] grounding [The Parthenon is colored], there is the relation D – the relation holding between the instantiation of a determinable and the instantiation of any of its determinates – such that it has at least some plausibility that it is part of the essence of [The Parthenon is colored] that it exists only if it stands in D to something. As I’ve argued in my discussion of building-based reductionism above, opaque grounding cases do not seem to involve any plausible candidates for building relations holding between the ground(s) and the grounded fact. Return once more to our non-naturalist embracing classical hedonistic utilitarianism in normative ethics. What could be a plausible example of a relation R such that, according to the non-naturalist, it holds between [a maximizes happiness] and [a is morally right], and it is part of the essence of the moral fact – part of its very identity, what it is to be that fact – that the fact only exists if it stands in R to something or other? The only candidate which seems to present itself is the right-making relation, or more precisely the relation R* which holds between a fact [P] and a fact of the form [x is right] whenever [P] makes x right.Footnote 25 Perhaps even a moral non-naturalist could accept that it is essential to a fact like [a is morally right] that it exists only if there is something which stands in R* to it. But the impression of progress here is merely illusory as far as reductionism is concerned. For what is the relation R* which holds between a fact [P] and a fact of the form [x is right] whenever [P] makes x right? I don’t see that there is any more content to a claim that [P] makes x right than that x is right in virtue of the obtaining of [P]. But if that is the case, the natural suspicion is that right-making relation is simply a restriction of the grounding relation to cases where the grounded fact has the form [x is right], and R* is simply the grounding relation. That, however, means that the relevant witness of clause (ii) of Essence II will read “[a is morally right] stands in the grounding relation to [a maximizes happiness], and [a maximizes happiness] exists”. Essence II would fail to be a properly reductive account of grounding. If Essence II can only accommodate opaque grounding cases by failing to be a properly reductive account, Essence II fails.Footnote 26 Consequently, even sophisticated essence-based accounts in the end fare no better than building-based accounts did when it comes to accommodating opaque grounding cases.

5 Further Issues

In this section, I will discuss some general issues pertaining to opaque grounding as a problem for reductionism. The first issue concerns the distinction between full and partial grounding. In the preceding, I have been working under the simplifying assumption that in the example illustrating opaque grounding, a non-naturalist will want to say that a particular moral fact (like [a is morally right]) is fully grounded by some set of particular natural facts. It is time to consider how the argument is affected if we relax this assumption. The example I’ve employed so far is that [a maximizes happiness] fully grounds [a is morally right], but what if the non-naturalist position is construed so that the former fact is only a partial ground for the latter?

Ultimately, I do not think this choice point affects the core of the argument substantially. Let us suppose [a maximizes happiness] merely partially grounds [a is morally right]. The dominant approach to the relationship between full and partial grounding has included a supplementation requirement such that any merely partial ground [P1] for a grounded fact [Q] needs to be supplemented with further merely partial grounds [P2]-[PN] such that [P1]-[PN] jointly fully ground [Q] (Rosen, 2010: 115; Fine, 2012: 50). On this approach, if [a maximizes happiness] merely partially grounds [a is morally right], there must be some further supplementing fact or facts that join up with the natural fact to constitute a full ground for [a is morally right]. If those supplementing facts are just further natural facts, that clearly will not affect the arguments of Sect. 4. An interestingly different non-naturalist position results by taking a particular moral fact like [a is morally right] to be fully grounded only by some set of particular natural facts together with a general moral principle.Footnote 27 While the exact form of such moral principles has been contested, the details need not concern us here. For it is clear that the reductive accounts discussed here will fail to accommodate a non-naturalist view construed in this way too. As we have already seen, the basic metaphysical commitments of moral non-naturalism entail that (e.g.) moral rightness is not built out of or reducible to anything natural, and that the essence of rightness – what it is to be morally right – does not involve the natural properties in virtue of which actions are morally right in any way. Consequently, those commitments will block the non-naturalist from taking [a is morally right] to have [a maximizes happiness] as even a merely partial ground on the reductionist accounts discussed in Sect. 4 above, for those accounts would still require that that natural fact either entered into the essence of the moral fact in question, or that the moral fact was at least partially built from or reducible to that natural fact. And it is exactly such relations of essential involvement and construction between the moral facts and their natural grounds that are ruled out by the basic commitments of non-naturalism, regardless of whether those natural grounds need to combine with further (possibly non-natural) facts to arrive at a properly full ground or not.Footnote 28 The guiding intuition behind this aspect of non-naturalism is that there is a fundamental metaphysical divide between the respective natures of the moral and the natural such that the natural grounds of particular moral facts are blocked from entering into the essence or constructional basis of those facts. Being merely partial grounds would not do anything to help the natural facts in question bridge this divide.

Another question concerns the relevance of my case against reductionism. If I am right, I have identified certain metaphysical theories which are incompatible with all the discussed reductive accounts of grounding. Since the relevant cases implied by those theories are by all appearances non-contradictory and fully conceivable, this would be an outright refutation of any reductive account formulated as a conceptual analysis. But none of the accounts on offer have been proposed as analyses of the concept of grounding, but rather as accounts of what the worldly phenomenon of grounding consists in. Clearly, such an account could be successful even if it rules out some logically conceivable cases of grounding. But there are reasons why reductionists should be uneasy about ruling out the cases of opaque grounding I have discussed.

Firstly, the reductionists I have discussed above typically seem to intend their accounts to be compatible with as wide an array of specific views of what grounds what as possible. When they are presented with apparent counterexamples to their preferred account, the response is to either modify the account, offer a reinterpretation of the cases, or provide a principled reason why the account does not after all need to accommodate them, rather than to flatly reject the cases.Footnote 29 Indeed, there is a general ambition in the grounding literature to try to keep doctrines about the nature and behavior of grounding as neutral as possible with respect to first-order metaphysical theories. In this vein (but in a different context), Shamik Dasgupta writes:

If (1), (2), and (3) are true, then general considerations about the nature of ground suggest that physicalism is false – our unacceptable result. To be clear, physicalism may be false. It might be that thinking about the nature of consciousness – for example, in conceivability arguments, knowledge arguments, and so on – reveals that physicalism is false. But this should not be revealed just by thinking about ground. (Dasgupta, 2014: 561)

This approach seems to speak equally against ruling out theories such as the relevant kind of moral non-naturalism based on purely ground-theoretic considerations. Thus, there is a general reason why reductionists should feel uncomfortable about ruling out opaque grounding cases.

Secondly, even if, in general, reductive accounts may sometimes rule out otherwise respectable first-order theories, one might feel uneasy about excluding some of the specific views committed to opaque grounding cases. Thus, for example, moral non-naturalism is a popular view in metaethics. Ruling it out is not a matter of just dismissing some farfetched point in logical space but renders one’s account of grounding incompatible with one of the main contenders in moral metaphysics. That is a substantive cost. The question of when and to what extent a reductive account should be allowed to restrict first-order metaphysical theorizing is a difficult methodological issue that I will not be able to address properly here. By the standards implicit in the current grounding literature, however, opaque grounding remains a considerable problem for reductionism.

Finally, there is a question about the generality of the problem. I have so far shown that four reductive accounts available in the literature fail to handle opaque grounding cases. While this is an interesting result in its own right, I also think there is good reason to believe that these results generalize sufficiently to constitute a broader problem for reductionism. As I have pointed out, the dominant assumption in the discussion over grounding reductionism has been that grounding needs to be explained in terms of some other heavyweight hyperintensional phenomenon. After all, an important catalyst for the current renaissance of interest in grounding was the realization that grounding could not be equated with purely modal relations like metaphysical necessitation or supervenience. And as we have seen in the discussion above, the relation between a grounded fact and its grounds in an opaque case is, in a sense, very thin: the former obtains because the latter does, but there do not seem to be any more specific and “thick” metaphysical connections (such as e.g. building or essential involvement) between the facts involved or their constituents.Footnote 30 But any hyperintensionalist reduction is likely to proceed by accounting for grounding in terms of phenomena which are taken to be less abstract and imbued with more specific content. It is thus correspondingly likely that any such account will be unable to accommodate opaque grounding cases.

However, there does remain one strategy possibly worth exploring for the reductionist: to give up on the assumption that grounding needs to be accounted for in terms of other hyperintensional phenomena and instead turn to some sophisticated modalist account. For even though grounding cannot be directly identified with any single modal relation, like necessitation or supervenience, it does not follow that it cannot be built out of some more complex collection involving such a relation. Thus, for example, recently McDaniel (2022) has provided an account which reduces grounding to a sophisticated form of minimal necessitation, thus explaining grounding in terms of the modal relation of metaphysical necessitation together with certain structural constraints on the grounds. Such an account of grounding seems to render the relation sufficiently “thin” to be able to handle opaque grounding cases. For example, the moral non-naturalist’s commitment to Distinctness, Fundamentality and Essential Isolation does not seem to present any obstacle to her accepting that [a maximizes happiness] minimally necessitates [a is morally right] (assuming, again, that the former is a full ground for the latter). Of course, it may be that the suspicion with which most grounding reductionists have viewed modalist accounts is warranted, so that there are other forceful objections to McDaniel’s account and other accounts like it. However, the challenge from opaque grounding seems to put pressure on the reductionist to either pay closer attention to the hitherto largely overlooked option of sophisticated modalism or otherwise reconsider their commitment to reductionism.

6 Conclusion

In this article, I have introduced opaque grounding as a problem for four representative hyperintensionalist reductions of grounding presented in the literature. I have argued that this problem likely generalizes to other possible hyperintensionalist accounts and that the problem cannot easily be dismissed, unless the reductionist opts for the largely overlooked strategy of providing some sophisticated account partially in terms of modal phenomena. If the assumption that grounding cannot be accounted for in such terms is upheld, the argument thus indirectly provides support for grounding primitivism, a view which has often taken on the status of unjustified orthodoxy in the grounding literature. I have here only been able to provide a brief sketch of the previously underexplored notion of opaque grounding and how it impacts one important question about the nature of grounding. However, sustained attention to opaque grounding promises to deliver equally interesting consequences in other parts of the discussion over grounding.

Notes

Many facts should perhaps also be thought to include a time to which they are relativized, but for simplicity I will ignore this aspect in what follows.

There are alternative treatments of grounding available – for example treating grounding as a relation between propositions (Rosen, 2010), as a relation between entities of heterogenous ontological categories (Schaffer, 2009), or via a sentential operator (Fine, 2012). I do not think the choice makes a difference to the substance of this article, and it would be tedious to have to constantly qualify grounding claims so as to be neutral on this issue. The substance of my argument should be readily translatable into one’s preferred way of regimenting grounding claims.

For something like this notion of metaphysical analysis, see e.g. Schroeder (2005).

While Väyrynen is right to note that non-naturalism takes moral phenomena to be metaphysically discontinuous with supernatural phenomena (such as divine preferences) just as much as with natural phenomena, I will not make this qualification explicit. The reader is invited to think of “natural” as shorthand for “natural or supernatural” in this context.

I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for encouraging me to discuss this point.

For a critical overview of non-naturalist arguments to this effect, see Paakkunainen (2018).

Naturalist moral realists contest this and attempt to show how properties and relations that possess the distinctively normative features that non-naturalists are concerned with can in fact be built out of wholly natural components that themselves individually lack those features. See e.g. Schroeder (2005: 9–17).

As Leary (2022: 797–98) points out, when Moore speaks of the kind of indefinability he wants to attribute to goodness, he contrasts it with verbal indefinability, and provides examples of the relevant kind of definition applying to things themselves, rather than our words or concepts for those things. (See e.g. Moore ([1903] 1993: 60–61). It thus seems like what Moore has in mind is something like a notion of real definition.

For a classic argument to the effect that supervenience is not sufficient for the kind of explanation theories in normative ethics strive for, see Depaul (1987). Berker (2018: 733–35) argues that early users of “supervenience” terminology in analytic moral philosophy associated with it both ideas of modal covariation and explanation, without always clearly distinguishing these.

Broad’s classification of moral characteristics as derivative should not be taken to imply that moral properties are non-fundamental according to the building-based framework for fundamentality I’m working with here. For nothing of what Broad says in the quoted passage implies that there are any building relations holding between non-moral and moral properties, and as I’ve argued above, a non-naturalist like Moore should deny any such claim anyway. What Broad here seems to be making a claim about is rather grounding connections holding between instantiations of properties, i.e. between facts. So if fact-grounding is a building relation, it is the moral fact [Experience e is good] which is non-fundamental in virtue of being grounded by [Experience e is pleasant], without there being any building relation between the properties instantiated in these two facts.

Similarly, W. D. Ross, another influential non-naturalist, writes: “[W]e may say that the difference between goodness or value and such attributes as yellowness is that whereas the latter are differentiae (i.e. fundamental or constitutive attributes) of their possessors, the former is a property (i.e. a consequential attribute) of them. And in this respect goodness may be compared to the properties that geometry proves to hold good of various types of figure. But if we recognize the affinity, we must also recognize the marked difference between the two cases. […] In the first place, it is quite arbitrary which of the attributes equilaterality and equiangularity is selected as the differentia of the kind of triangle which in fact possesses both; it is just as proper to say that the relative size of the angles determines the relative length of the sides, as vice versa. Value, on the other hand, seems quite definitely to be based on certain other qualities of its possessors, and not the other qualities on the value. In fact the distinction between differentia and property as fundamental and consequential attributes respectively is far more appropriate in this case than in most of those to which it is applied, since this is one of the comparatively few cases in which one of the attributes is objectively fundamental and the other objectively consequential. We might call value a genuine as opposed to an arbitrarily chosen resultant (or property).” (Ross, [1903] 2002: 121)

A property F being instantiated in a ground should be clearly distinguished from F being instantiated by a ground. The property of being a fact is instantiated by [a maximizes happiness] without being instantiated in that fact, whereas the property of maximizing happiness is instantiated in the fact while arguably not being instantiated by the fact.

In a similar vein, Leary (2022) provides an elaborate characterization of the naturalist/non-naturalist divide in ethics which she sums up as non-naturalists holding that some normative properties “are neither identical to nor have essences that ultimately involve paradigm non-normative properties.” (2022: 805).

Jaegwon Kim attributes to the British emergentists a view according to which “the supervenient, or emergent, qualities [of mind] necessarily manifest themselves when, and only when, appropriate conditions obtain at the more basic level; and some emergentists took great pains to emphasize that the phenomenon of emergence is consistent with determinism. But in spite of that, the emergents are not reducible, or reductively explainable, in terms of their ‘basal’ conditions.” (Kim, 1990: 7) If “determinism” is here intended in a sense according to which instantiations of base properties metaphysically determine the instantiation of emergent properties, the emergentist view Kim describes might well be a historical example of an opaque grounding view. Regardless of what the British emergentists actually believed, an opaque grounding view of the mental seems like an interesting theoretical option.

For a discussion of something like this view, see e.g. Sturgeon (2007).

Obviously, for all the views outlined here beyond moral non-naturalism, the commitments will have to be reformulated to involve different families or domains of properties and relations. This should be straightforward enough to leave as an exercise for the reader, perhaps except for the non-reductive moral naturalism discussed last. Such a view would lack any analogue of Distinctness, and Fundamentality would have to be reformulated to drop the reference to non-natural moral properties and relations.

The central work here is Bennett (2017).

The idealization here involves ignoring the complication that we need some restriction on the range of eligible properties in the principle, since plausibly not all the properties of a constituting object are inherited by the constituted object.