Abstract

We critically reflect on a conservation project in the Ecuadorian Amazon that was designed to promote biodiversity conservation among lowland indigenous communities involved in eco-tourism initiatives by teaching them how to knit a particular set of local animals. We use interpretive qualitative research and draw on social practice theory to examine the ways that participants’ engagement with new knitting in participatory knitting workshops changed the understanding of environmental conservation and social entrepreneurship within an eco-tourism context. Eventually, the intervention pushed participants to adopt new and difficult-to-sustain conservation and entrepreneurial practices. The introduction of these new practices and a focus on a specific list of local species turned animals into commodities and created unsustainable connections with new materials and a disconnect between local and traditional know-how.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: snakes and turtles over hats and gloves

Even though she is not a knitter, Maria Cristina was the co-founderFootnote 1 of a knitting for conservation project for members of lowland indigenous (Kichwa) eco-tourism associations in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In collaboration with her co-authors, she looks back on her experience with this knitting for conservation project. Together we critically reflect on the way the knitting workshops pushed participants towards adopting behaviours and attitudes aimed at conserving a particular set of local species through economic incentives and by developing social-entrepreneurial skills.

The knitting project relied on participatory social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) approaches, which are often billed as ‘bottom-up’, ‘culturally sensitive,’ and ‘inclusive’ (see Lennie & Tacchi, 2013; McKee et al., 2014). Following SBCC standards, knitting workshops were developed around people’s interests to enhance their knitting skills. Simultaneously, the project aspired to change peoples’ behaviours towards particular ‘correct’ forms of conservation and social ‘innovative’ entrepreneurship skills to add to their eco-tourism services and activities. This article presents a different point of view, emphasizing how, at least during its first three years and during the involvement of Maria Cristina (2015–2018), the knitting project brought only certain systems of knowledge—an individual-centrism and embrace of neoliberalism—while unintentionally side-lining longstanding indigenous Kichwa conservation and economic practices surrounding both knitting and human-nature relations.

Accordingly, this article looks at the way the project adopted individual-centred social and behaviour change SBCC strategies and policies to influence project participants, through so-called participatory and inclusive approaches, to do things, and say things in a certain ‘right’ way, which might have largely ignored people’s own systems of knowledge, culture and practices related to social entrepreneurship and environmental conservation (see also Gegeo & Watson-Gegeo, 2002). Specifically, we link Maria Cristina’s personal experiences with the project to Shove’s (2010) critique. Shove’s (2010) critique emphasizes the way that economic and individual-centred approaches and ‘lexicon’ used in environmental-related interventions focus on changing attitudes (A) and behaviours (B), and keep in place prevalent ideas on the role of individual responsibility and choice (C). In other words, people are made responsible for changing their behaviour to achieve environmental conservation, while broader structural concerns are largely ignored. According to Shove et al. (2012), ABC interventions stand in the way of holistically addressing environmental challenges or the systems of inequality and power implicated in SBCC programs.

Shove and colleagues (2012) argue that individual-centred ABC approaches have become too prevalent in environmental policy-making and as such, do not leave room for alternative options to seek change beyond a specific set of attitudes and behaviours or animals and species. By so doing, putatively external, ‘correct’ understandings of what environmental conservation should be—solutions for biodiversity losses are situated in individual attitudes and behaviours—are kept in place (Shove & Walker, 2010). The same can be said about participatory approaches within SBCC interventions. Participatory approaches can, often enough unintentionally, reproduce systems of power and inequalities by directing participants’ capacity to act in a particular space, namely that of individual attitudes and behaviours (see also, Gaynor, 2014; Watson, 2016). In other words, even participatory approaches tend to continue to use preferred institutional arrangements that might not be consistent with participants’ interests and ways of doing things (Mosse, 2001).

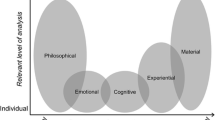

In comparison, Shove (2010) places the social in the ‘praktik’, “a routinized type of behaviour which consists of the use of interconnected elements” (Reckwitz, 2004: 249): meanings, skills and materials. A focus on practices can provide a holistic comprehension of behaviour and social change (Barranquero Carretero & Sáez Baeza, 2017) and a better understanding of the contextual conditions of everyday life (Nicolini, 2012) and culture in relation to the environment. This means that Shove’s three-element-model allows for looking at the intervention from a different perspective. This view examines knitting as a practice comprised of meanings, skills and materials, where “meanings refer to ‘symbolic meanings, ideas, and aspirations’; skills to ‘competences, know-how, and technique’; and materials to ‘things, technologies, tangible physical entities, and the stuff of which objects are made’” (Shove et al., 2012: 14). Moreover, Shove’s model provides an opportunity to question participatory approaches within SBCC interventions and see them as a space where it might be possible to: (1) deconstruct concepts and meanings related to environmental conservation (Arts et al., 2013) and social-entrepreneurship; (2) illustrate how some meanings and understandings related to the environment and social-entrepreneurship become more dominant than others (Shove et al., 2012); and (3) look at the ways in which meanings and understanding related to environmental conservation are linked, embedded and re-enacted in elements of practices within participatory approaches (Arts et al., 2013). Moreover, in agreement with Turnhout et al. (2013), we contend that social practice theory (SPT) can widen the perspective by taking into account aspects of culture and local know-how, which are normally not found in ABC approaches.

Looking at how participants’ engagement with knitting in participatory workshops is shaped by the organizers’ understanding of environmental conservation and social entrepreneurship presented by this program allows us to observe the way that people engage and are influenced into adopting new ways of doing things. In other words, it allows us to uncover how “practices emerge, persist, shift and disappear when connections between elements of these three types are made, sustained or broken” (Shove et al., 2012: 15), for example, when materials such as yarns and particular knitting techniques (skills) shift alongside the meanings linked to conservation and social entrepreneurship. Thus, we can see the role of context and history of, in our case, knitting practices and how they changed over time. Similarly, we can see through the workshops and the way that institutional policies and strategies replicated aspects of neoliberal ideologies through social innovation interventions. Simultaneously, by looking at the project from a different perspective—SPT—we are able to identify and acknowledge local practices according to participants’ shared meanings of ‘conservation’ and ‘social-entrepreneurship’ within a participatory setting, and how they use materials such as pita according to their own skillset (Halkier et al., 2011). Thus, we are able to move beyond the common dominant individual focus. By concentrating on practices and their elements instead of individual behaviours, we demonstrate how the knitting project could have integrated a more holistic and cultural-sensitive approach. This would have allowed the intervention to better include local know-how and steer away from a focus on a particular set of policies, list of animals, and strategies based on priorities developed outside the community, and towards how participants would prefer to tackle environmental changes and, if at all, engage with neoliberal entrepreneurial systems.

2 Study area

The lowland KichwaFootnote 2 in the Amazon are one of the largest language groups in the Napo region (Davidov, 2013). Families from 10 to 100 or more are widely spread throughout the forest (Davidov, 2013). Moeller (2018), Andy Alvarado and colleagues (2012) and Uzendoski (2005) observed that lowland Kichwa communities have profound knowledge and an interlaced relationship with their environment (see also Bilhaut, 2016). The forest is historically and today an important part of their livelihood, in terms of health, shelter, food, handicrafts, etc., with a main source of sustenance being agriculture, fishing, and hunting (Chicaiza-ortiz, 2022). In this context and as Uzendoski (2005) shows, Kichwa life, including economic activities, is centred around the creation and maintenance of social relationships, which is achieved through particular rituals e.g. as they surround marriage and also through orienting all economic decision making towards social reproduction. This orientation has contributed to a complex, often tense, relationship between Kichwa and globally dominant capitalist systems of economic production and consumption and their visions for economic well-being and environmental sustainability (Lyall & Valdivia, 2019; Uzendoski, 2005). Kichwa communities have variously and creatively engaged with these tensions, resisting, for example, oil extraction but also acquiescing to it based on their interests, needs and values and hopes for a sustainable future (Lyall & Valdivia, 2019).

Kichwa communities also negotiate these tensions in an increasingly difficult context. Indigenous territories are significantly showing the effects of not only population growth but also forest degradation, the impact of climate change, and natural resource extraction (Lyall & Valdivia, 2019), and tourism (Marcinek & Hunt, 2015; for other contexts see Fletcher & Neves, 2012). Because of these environmental changes, longstanding local livelihood systems are no longer sufficient to meet Kichwa day-to-day needs, and therefore indigenous communities have been pushed into finding ways to more actively engage with a neoliberal economic system, for example, through eco-tourism associations (Marcinek & Hunt, 2015). In addition, lowland Kichwa communities in the Amazon are being influenced by the creation of biological reserves and the development of new governmental institutions, such as [Sumak]Footnote 3 that is strongly focused on promoting innovation and linking science to community programs (see also Moeller, 2018; Wise & Carrazco Montalvo, 2018). Simultaneously, external actors regularly overlook Kichwa values—their emphasis on social reproduction and human–environment relations—because they don’t fit dominant neoliberal individual-centred policies and strategies, which are normally used in conservation interventions. The knitting project, as discussed in this article, is exemplary of this tension between Kichwa communities and external visions for a sustainable future.

3 Introducing the knitting workshops

When organizing the knitting workshops, Maria Cristina was employed by [Sumak] (created in December 2013). [Sumak] is located in the Amazon right next to the Biological Reserve Colonso Chalupas, established in 2014. As Moeller (2018) describes, [Sumak] was created with the aim of focusing on the education, study, and research of natural resources and biodiversity, especially around the Biological Reserve Colonso Chalupas. Simultaneously, [Sumak] was founded to provide support for the creation of sustainable social-entrepreneurship initiatives with local communities (see Wise & Carrazco Montalvo, 2018; Moeller, 2018).

At the beginning of 2016, right after Maria Cristina joined the cultural centre at [Sumak] (within the community engagement department), the president of a Kichwa community approached Maria Cristina and Caroline Bacquet (the other co-founder) about creating the knitting workshops. He provided the names of people interested in improving their knitting techniques and skills. The community wanted to learn techniques for knitting woollen hats, gloves, carrier bags, house decorations and baby clothes. However, this interest did not fully align with the priorities of [Sumak]. In other words, in order for [Sumak] to support the knitting project, it had to adhere to governmental educational, environmental, innovation and development policies that promoted sustainable environmental conservation and socio-economic transformation and that, in practice, reflected dominant ABC approaches. Hence, rather than improving knitting techniques for hats and carrier bags, Maria Cristina and Caroline had to suggest a conservation-focused programme that aimed at improving participant’s livelihoods through innovative entrepreneurship and for the workshop to influence participants into changing their attitudes and behaviours towards the conservation of a particular list of animals.

Maria Cristina and Caroline assumed different roles in the project. Caroline was hired as part of the Life Sciences Department by [Sumak] to do research in cell and molecular biology and genetics. In her spare time, she knitted. Her advanced amigurumi crochet skills supported the creation of the knitting workshops. In other words, Caroline brought to the project pragmatic knitting skills as well as the particular perspectives of a natural scientist with an interest in environmental conservation (see Bacquet-Pérez & Batres-Quevedo, 2019). In comparison, Maria Cristina was neither a knitter nor a natural scientist. Instead, she approached the workshops from the perspective of policy and strategy implementation and creation, including project coordination, with a background in the social sciences.

Institutional framework and Maria Cristina’s shifting positions substantively influenced the creation, implementation, and evaluation of the knitting workshops. For example, when Maria Cristina was the director of the cultural centre at [Sumak] she focused on policies and strategies to support the creation and implementation of cultural activities such as Ecuadorian cinematography (see also López Pazmiño et al., 2019), combining local art with chemistry, book reading, and others, to engage and empower indigenous communities around and close to [Sumak] (see also Wise et al., 2020). The knitting for conservation workshops were developed around the communication of science to, in particular, non-scientist indigenous communities. However, when Maria Cristina changed positions and joined the innovation department, she shifted to a focus on supporting eco-tourism associations in establishing social-entrepreneurship concepts and services as part of the knitting workshops (see also Etzkowitz, 2002).

Maria Cristina shared the knitting project concept of knitting local animals with the presidents of various eco-tourism associations. They presented the new concept in their monthly community meetings to discuss amongst themselves what they thought about knitting local animals instead of carrier bags and hats, and if they wanted to dedicate time to it. After a couple of weeks of continuous communication and negotiation, the presidents of the three eco-tourism associations approached Maria Cristina to let her know that the people expressed interest in participating in the project. Thereafter, Maria Cristina immediately led fundraising efforts with local businesses to get the materials needed for the knitting workshops and to, later on, support the knitting project by displaying the knitted animals at their business.

In this case, Maria Cristina undertook intercultural dialogue and what she thought were participatory, inclusive, and bottom-up efforts (see also Tufte & Mefalopulos, 2009) to ensure cultural sensitiveness and adequate organization of the knitting workshop according to participants’ interests, needs, and time availability. As SBCC interventions do (see Schramm, 2006), Maria Cristina shared information about the conservation of a particular list of animals and the project through mass media channels including radio, Facebook, and TV. Maria Cristina was told by various communities that they have limited access to Wi-Fi, computers, and cell phone networks, a common challenge for remote indigenous communities (see also Hobbis, 2020). Participants expressed that “the internet culture is very low” (field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018) and does not allow for reliable project engagement and empowerment. Communication, therefore, had to be face-to-face and consider communities’ communication structures.

After setting up the project with indigenous eco-tourism associations, the project implemented an internal [Sumak]-based process with three focus areas: First, environmental education through community engagement (see the other co-founder’s account Bacquet-Pérez & Batres-Quevedo, 2019). [Sumak]’s research studies suggested the need to develop environmental education programs, communication campaigns or interventions around the conservation and protection of slow-moving terrestrials around the Biological Reserve Colonso Chalupas (see also Filius et al., 2020), and local amphibians and reptiles. Secondly, external conservation values were adopted from a national communication campaignFootnote 4 that embedded information from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) “red list” (see also Moeller, 2020). This communication campaign was supported by [Sumak], and thus, motivated both project founders to steer the project’s conservation focus on international conservation values and expand the focus on a particular list of species.Footnote 5 Thirdly, the goal was to empower participants to improve their livelihoods (in particular, women's) with social-entrepreneurial skills, and motivate participants to embed new conservation knowledge through the knitting workshops. Thereafter, the project was aimed at incentivizing the ‘protection’ of the animals with a high conservation value, mentioned on the list, and at allowing for selling the knitted products to tourists through participating communities’ eco-tourism associations (see also Etzkowitz, 2002).

During Maria Cristina’s time at the innovation department of [Sumak], a total of 15 knitting and social-entrepreneurship workshops were organized between June 2016 and June 2018, engaging a total of six different Kichwa communities. Participants ranged between 16 and 50 people maximum per workshop. Out of the six communities, three already had a settled eco-tourism association and the other three were thinking of developing their own eco-tourism associations. For this article, we will focus on those knitting workshops that integrated a social-entrepreneurship approach and a neoliberal approach to conservation for which Maria Cristina was primarily responsible.Footnote 6

For each workshop, Maria Cristina prepared visual communication materials (e.g. flyers and tags) with biologists, while the other co-founder prepared the knitting instructions based on the biological characteristics of the animals on the list. Maria Cristina proceeded with the design, printing and distribution of the flyers, knitting instructions, catalogue, and animal description tags so that participants would learn how to emphasize to tourists the biological characteristics of the local species, together with their ‘high’ economic, conservation and cultural value (see Fig. 1). This is also an example of the way that dominant ABC approaches were replicated in the workshops. In parallel to the knitting workshops Maria Cristina engaged with eco-tourism and community members to establish a brand and its first social media page on Facebook. These communication items were used to establish partnerships with businesses and institutions to sell the products and provide conservation values through sales. Each knitted animal came with detailed information about its conservation value based on IUCN conservation standards. Tourists were told that they could support conservation efforts and Kichwa women’s livelihoods when they bought a knitted animal. In sum, the project combined conservation values with neoliberal economic incentives, which later became part of a broader phenomenon within the United Nations environmental sustainability agenda.Footnote 7

4 Methodology

This paper reflects on how behaviour and economically oriented approaches shape the design and implementation of conservation initiatives such as the knitting workshops by drawing on Maria Cristina’s experiences as a co-founder of the initiative as well as qualitative research with Kichwa participants. Inspired by auto-ethnographic approaches to research, the authors re-think and explore personal experiences and connect them to observations and insights related to a broader set of meanings, understandings, and debates (e.g. see Collins & Gallinat, 2010; Koot, 2016). Doing so, also allows for highlighting previously unseen or taken-for-granted practices that seem to have influenced participants’ interests in adopting the knitting for conservation practice.

In addition, qualitative data on the knitting project were collected through a research affiliation with an Ecuadorian non-profit organization, Colonso, and the support of a research assistant. Through this affiliation, Maria Cristina was able to engage with workshop participants from the three eco-tourism associations participating in the knitting and social-entrepreneurship workshops not just as a co-organizer but also as a researcher. She discussed with them that this research would likely be part of her Ph.D. and that she wanted to publish an article about the experience gained from the knitting program. The three associations gave her their full consent for using information that was observed during the knitting and social-entrepreneurship workshops. Participants further consented to engage in in-depth-semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions including permission to record the interviews (signed consent forms). A local research assistant, whom Maria Cristina trained, supported and conducted some of the in-depth-semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions. A few of the participants expressed that they did not want their names to appear on the paper. She recorded and transcribed the interviews verbatim and translated them from Spanish to English with the support of an English native speaker. She coded and categorized interview data according to themes emerging from discussions. Moreover, she received approval to look at the knitting project from Graham Wise, the vice-president of innovation and governing board member from [Sumak] and President of Colonso. In terms of limitations during data collection, some interviewees participated in the workshops many times, others just once or a few times during the different stages of the knitting program. This might have influenced some participants more than others into adopting external conservation values or combining conservation with neoliberal economic values.

5 Results: do you see what I see?

For our analysis, we contrast Kichwa traditional knitting practice with the new knitting for conservation practice. We critically look at: (1) meanings: the way that the different knitting practices reflected different meanings and understandings associated with ‘knitting’, ‘conservation’, ‘social-entrepreneurship’, and ‘sustainability’; (2) materials: how new materials were introduced (e.g. wool and crochet) and what that did to participants’ own thread (pita) made out of local plants and trees; and (3) skills: how the knitting practice provided new knitting skills by introducing a Japanese way of knitting and new ways to manage economic gains from selling the knitted animals. In other words, we consider how all these three elements shifted because of the new knitting for conservation practice, the way that people became carriers of the new practice, and the sustainability of new practices (Table 1).

5.1 Meanings

Meanings are “symbolic meanings, ideas and aspirations” (Shove et al., 2012: 14). Traditional knitting practices encompass a multiplicity of meanings and understandings for indigenous Kichwa communities in the Ecuadorean Amazon. During the knitting workshops, community members showed project organizers a display of their traditional knitting practice. This varied from knitting fishing cages to jewellery with seeds, hammocks, baskets, nets with pita, and pottery with natural clay. Also, the meaning of knitting has changed over time because of external influences, such as schools or nuns that would visit communities and teach them how to knit differently (Tocancipá-Falla et al., 2018). As one of the participants expressed: “In school, they teach us how to knit carrier nets, and handbags. My mother always with the Shigra (a.k.a carrier bag)” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). When the knitting workshops started, they further shifted participants’ knitting, in this case, from knitting sweaters, carrier bags, and hats that were for personal use to knitting animal toys for tourists for external purposes.

During the workshops, organizers quickly learned that participants gave negative meanings, and thus, assumed they had a negative relationship with certain animals on the list (in particular, the coral snake, Micrurus surinamensisFootnote 8). Maria Cristina saw this as an opportunity to influence participants into changing their negative meanings/relationship with the animals towards more ‘positive’ international policy-driven conservation meanings. She found this confirmed when, after a couple of workshops, participants started to express what, in the eyes of the organizers, seemed to be a ‘positive’ attitude and behaviour change towards the animals with previously negative meanings.

During the focus group discussions and in-depth-semi-structured interviews, one participant described the importance of protecting the Micrurus surinamensis by using natural deterrents (swatches of nettles) to remove coral snakes from homes rather than killing or manhandling them. Another participant expressed a new desire to conserve the animals that they were knitting in the workshops: “To protect the animals... much more, to be conscious and conserve, that we have to keep that kind of animal” (Field interviews, 2018). Another one explained, “I like all the colours, I like to see it, I’m curious” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). Also, “the coral snake is part of oneself. The colours give you much joy. It is a combination of colours that give you a lot of energy . . . that motivation, that desire to knit. The same colours that attract you, also give you much hapiness” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018).

The traditional way of seeing the colour red on the Micrurus surinamensis was related to danger. This meaning shifted from bad luck to good luck, joy, and protection. Another participant added, “The white and red colours mean protection to us. We have to explain to the tourist that it is good luck. The colour it has is so cute” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). Participants showed program organizers that they tried to give new ‘positive’ meanings and conservation attributes of the Micrurus surinamensis and new ways to relate to them—at least in conversations with Maria Cristina as an organizer, and, thus, as representative of these proposed new meanings.

Because she embraced the ABC perspective, Maria Cristina’s evaluations missed the way that participants gave conservation meanings. Those meanings were not based on the criteria that placed the species on the list. Participants have respect for and value their relationships (whether it might be negative or positive) with all the natural elements that surround them:

… we have a strong relationship with those animals. I do not know what each animal means [scientifically] but my parents and my grandparents also told us, I remember little by little that each animal has a relationship with us, and the truth is that now I realize because I love what is the nature and animals and everything that is related to that. I think that if sometimes you identify with an animal or something, it has some connection with you (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018).

This relational emphasis is also echoed in Moeller’s description of indigenous perspectives on animal-human relationships when she notes that “for the Napo Runa, animals and plants and certain inanimate objects are not qualitatively different beings from humans: they have the same subjectivities, they experience the world from an I-point of view. For their survival and well-being, human beings are dependent on making alliances with non-human people” (2020:1). By trying to adhere to ‘external’ dominant policy-driven conservation values to protect certain animals on the list, the workshops blindsided participants’ way of relating to those animals. This means, that the knitting workshops shifted participants’ intricate connection/relationship to not only the environment but also the animals on the list.

Right after the social-entrepreneurship component was added to the workshops, participants were further pushed to feel responsible for protecting the list of species for a financial benefit (Kiik, 2018). For example, participants became carriers of new meanings associated with the Micrurus surinamensis by engaging with tourists so they could support conservation values by buying a knitted animal. The meaning shifted from a relational value (human-animal relations) to a capitalist value (human-capital relations). In other words, by combining conservation with entrepreneurship values, the knitting practice seemed to have replicated meanings associated with eco-tourism practices where they link conservation with tourism (local and foreign) and financial benefits (Wunder, 2000), a meaning that already partially existed because of previous experience with eco-tourism services among participating communities.

We also observed a shift in meanings associated with gender roles linked to the combination of conservation and entrepreneurship. Women were responsible for knitting handicrafts such as the initially desired hats. In comparison, men showed interest in knitting during the workshops because they were knitting animals to sell to tourists. Moreover, the elderly embraced the meaning of the knitting practice. Maria Cristina’s individual-centred perspective caused her to see this acceptance as a sign of project inclusivity of commonly marginalized community groups. The interest shown by the elderly meant that they saw this project as an opportunity to still have an ‘economic-productive’ role in the community. This meant that they could replace hard work on the land by an easier practice such as knitting from home. The same goes for people with disabilities. The knitting practice shifted the meaning of being ‘productive’ among gender roles, the elderly, and people with disabilities in the neoliberal sense, within an eco-tourism association.

5.2 Materials

Materials refer to “things, technologies, tangible physical entities, and the stuff of which objects are made” (Shove et al., 2012: 14). Kichwa communities in the Amazon have a long-lasting knitting tradition with natural materials around them which has been passed on from generation to generation. Traditionally, participants knit Shigras, nets, and hammocks with pita, a thread from a Bromelia known as Aechmea magdalenae (Hornung-Leoni, 2011). Kichwa participants use natural elements (pita, seeds, leaves) that surround them to knit different things (e.g. nets, fishing cages, baskets) (see Fig. 1). The amount of work associated with making pita can take between 4 and 6 hours per thread, depending on how fast the thread can twist on your hands and shins. Additionally, there is a drying and colouring process after the twist.

The traditional knitting practice has adopted new materials over time (e.g. needles, threads, cloths) because of the influence of colonialism, schools and religious institutions (Andy Alvarado et al., 2012). Accordingly, many participants, who were all connected to the three eco-tourism associations, already had experience knitting with needles and wool prior to the knitting for conservation project. However, the project also introduced new materials by providing them in workshops: crochet and synthetic wool. Therefore, participants shifted their use of natural materials (pita) with their hands further to synthetic wool and crochet.

Synthetic wool, a material that lasts a long time and does not require a long preparation time, was adopted quickly during the knitting workshops. This might be because Kichwa communities are looking for alternative, longer-lasting materials because their natural resources are slowly disappearing. Some participants expressed that they see a change in their environment, “we see fewer animals and less biodiversity” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). Also, community members are externally influenced to look for other materials by thinking that, by so doing, they are contributing to conservation efforts while protecting their traditional knowledge. In the words of one participant: “community artisans are looking for ways to replace natural materials, by using artificial materials we can protect nature and preserve traditional knowledge” (Field interview, eco-tourism associate, 2021). However, introducing new materials might eventually also devalue the relationship that participants have with their own natural materials and might no longer support the conservation and production of natural materials (e.g. pita). A participant expressed “since pita is a natural material, when it gets wet it doesn’t last very long. The Colombian plastic thread lasts longer” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018).

Participants also shifted how they obtained materials for their handicrafts as a result of the workshops. Participants used to access materials for free, while wool and crochet need to be purchased at the city centre. This includes the need for transportation costs, negotiations with business owners and purchasing the needed materials (according to specific animal colours). Maria Cristina did not realize that purchasing wool and crochets might cause a big challenge for the sustainability of the knitting project because participants are not used to purchasing wool and crochet. They had to learn how to access these materials. Participants always expressed that they had a hard time finding and purchasing materials but Maria Cristina didn’t see that the process of acquiring materials was different from what the participants were used to. But it was. The knitting project, thus, meant a shift from in some ways unlimited, free access to materials from their surroundings to knitting with materials that were hard to find and pay for. This might jeopardize the project eventually, while simultaneously replicating neoliberal systems within eco-tourism associations.

Another key material shift is linked to the colour schemes of the knitted animals. Biologists deemed it crucial to get the right materials in terms of colours. Each knitted animal had to have the ‘correct’ biological colours, so that the value of the knitted animal would be higher because of its biological accuracy to endangered animals. For example: a colourful knitted turtle or snake that was sold in the market had a value of 3USD while, the biologically accurate turtle or snake could sell for up to 15USD. It couldn’t be a different tone of red for the Micrurus surinamensis, because then the biological and conservation aspect of the species would change, as well as the economic value of the knitting. However, even if there were businesses in town that sold wool, the colour tones that matched the colours of the animals on the list were not always available. The few businesses only sold cheap synthetic wool that better lasted in humid climate, such as the Amazon and that people used for hats, sweaters, etcetera. The costs for natural wool were almost three times higher — 5USD per skein in the capital, as compared with 1.50 to 2USD for synthetic wool. Local businesses did not sell certain colours for a lack of buyers. The crochet hook offered a similar challenge because the right size and handle for knitting the particular size of the new wool would not be available. Because of this, at least initially, the required materials needed to be bought in Quito, the capital. Later, one retail business was able to bring the needed colours and crochets (from the capital and other places within and outside the country), thus, further ensuring an increased dependence on externally produced and only through cash-based economic activities attainable knitting materials.

5.3 Skills

Skills are “competences, know-how, and technique” (Shove et al., 2012). In terms of knitting skills, participants expressed that their traditional knitting know-how is to knit with natural materials and that they learned how to knit with needles, threads, and wool in school. However, the knitting for conservation project introduced new knitting skills, a Japanese knitting technique that combined new knitting patterns and knots using wool and crochet, named Amigurumi (aka Amigurumi: Ami means “woven” and nuigurimi means “stuffed toy”). This technique presented the skill of converting local animals into cute knitted toys (Ramirez Saldarriaga, 2016). One participant expressed: “I have never knitted animals in my life. Only tapestries, flowers, dresses, hats, and little boots for children. Wow! This knitting has been a new big surprise in my life, that presents new things. I love all the knitted animals” (field interview, eco-tourism associate, 2018). Another participant added, “No, those animals no. This is the first time we are seeing [knitting] the manduru machacuy of the Amazon, and now we were thinking of knitting monkeys and also toucans” (field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). In sum, participants shifted their traditional knitting skills with natural materials to knit baskets, shigras, and hammocks to Japanese knitting skills using wool and crochet to knit animals.

When the knitting project introduced ‘the correct’ dominant conservation skills during workshop discussions that focused on the exchange of scientific and traditional knowledge, for example, while participants shared that they did not like coral snakes, the workshops showed how to first identify and then protect fake from venomous coral snakes. Many participants indicated that they learned something new about how to protect the Micrurus surinamensis and their mimics. By giving new information on how to identify and protect the animals on the list, participants were expected to embed these skills and protect the species on the list because of the project organizer’s externally determined and dominant conservation values. Because the knitting project was focused on a specific list of conservation behaviours and the ‘right’ skills she unknowingly dismissed that participants’ conservation skills were attached to participants’ personal relationship with the animals. Reflecting on this perception through SPT, we realized that it is not about focusing on a particular set of animals. Instead, we were able to see that participants’ relationships with animals were part of a much bigger network. Participants would constantly tell Maria Cristina about their relationship with nature and how everything comes together through relationships. But because this explanation didn’t fit within the project evaluation criteria, this information was side-lined.

Moreover, during the workshops, participants had to learn new communication skills. The use of scientific language and new concepts associated with the conservation of the listed animals represented a challenge. Maria Cristina found that some of the words such as ‘innovation’ and ‘science’ did not have an equivalent translation in the Kichwa language, so she looked for alternative words available in the Kichwa language (taripachick: to do research, mushukyachi: to become something new, or iñana: grow) to try to explain the goals of [Sumak]. In addition, participants gave descriptive kichwa names to the animals on the list. For example, the scientific name for the coral snake is Micrurus surinamensis (Aquatic coral snake) and the name in kichwa is Manduru Machakuy which means the snake of ‘achiote’ red colour. Looking at skills and the introduction of new scientific words to describe the species, shows that the participants had different ways of categorizing the listed animals, such as categorizing the coral snake by its red colour.

Additionally, all participants highlighted that while the younger generation communicated better and sometimes only in Spanish, most adults and the elderly preferred to communicate in the indigenous Kichwa language. During the workshops, the knitting instructions were given in Spanish, and scientific language was used to describe the animals on the list. This caused participants to speak to each other in Kichwa and then translate back into Spanish. To change concepts and meanings of conservation, innovation, cultural relationship with animals, and science, participants had to learn new concepts. Besides, a focus on skills showed that participants shifted the way they categorized animals, from a relationship-based meaning to a more dominant external ‘scientific’ way of categorizing animals on the list.

Beyond these conservation and scientific skills, the new skills strengthened Kichwa participation in neoliberal economic practices. By sharing these new skills, eco-tourism associations could offer services that could better attract tourists in conservation efforts. “We have to be careful that we are in tourism, take care of this species, the coral snake, we cannot harm it” (Field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). Now, looking back, we could see that participants only adopted the new conservation skills to involve tourists in conservation efforts and sell the knitted products. In other words, the knitting workshops shifted participants’ conservation skills from a traditional relationship to one adhering to external IUCN conservation skills with the aim to involve tourists in doing conservation and buying their knitted products.

When Maria Cristina introduced social-entrepreneurship skills in the workshops, the aim was to increase the quality and financial economic value of knitted handicrafts to be sold to tourists. Participants were taught how to present the knitting animal to tourists according to the IUCN conservation values of the species. In addition, participants learned how to manage their new income. Most participants did not have a bank account and some shared their earnings with other community members. Some found ways to spend the earned money immediately. One of the participants described the way they managed the money they made after selling some of the knitted animals, “Sometimes we forget how things work here, we do one thing, then another and then something else and then we don’t have money. That is what happens” (field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). The workshops, accordingly, sought to teach participants how to put earned money aside to sustain the need to buy wool, crochets, and print predesigned labels, and to give themselves an income. Participants were trained to put a financial value on knitting time, replicate the biological characteristics and knitting quality (e.g. the pattern had to perfectly be knitted from beginning to end, same pattern and no mistakes in between, and biological accuracy, meaning that the knitted animals had to look identical to the real animals). For example, one participant explained that “I sold my coral snake at $10 [not $15] because I haven’t perfected the quality of the knitting [animals] yet” (field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018).

Crucially, even after various entrepreneurship training sessions, participants always expressed that the biggest challenge in sustaining the knitting project was to have money to buy materials. “We have a problem with wool, because wool does not exist here” (field interviews, eco-tourism associate, 2018). A focus on skills showed that eco-tourism associates had a different way to manage their finances and that the workshops demanded participants to shift their skills on how to manage their products and income according to mainstream business economic systems. To better support project objectives in terms of sustainability, money management and finding materials (wool), the project could have benefited from implementing aspects of local know-how instead of dismissing them, for example, by recognizing and more explicitly drawing on the non-entrepreneurial interests for knitting hats or gloves, as initially requested by participating communities.

6 Discussion

The knitting for conservation project aimed to ‘positively’ change participants’ attitudes, behaviours, and the consequent choices individuals made. Social practice theory (SPT) criticizes such behaviour change interventions for creating unsustainable practices, (knowingly or unknowingly) side-lining aspects of culture and history, and duplicating existing policies and strategies by focusing on single interests and putting the responsibility of change on the individual. By using a practice-based approach to analyse Maria Cristina and participants’ experiences with the knitting workshop between 2015 and 2018, we were able to look back at the project experience and data with a different perspective. This perspective allowed us to obtain a deeper and better understanding of how a knitting for conservation intervention significantly altered indigenous Kichwa practice in such a way that meanings, materials and skills shifted. We found that participants became carriers of new knitting, economic and conservation practices, as well as how the intervention replicated neoliberal values from an eco-tourism setting. In other words, we found that by using dominant individual-centred behaviour change approaches this intervention (unknowingly) created an unintentional cultural disconnect between people from animals, diminished the use of natural local materials, and moved away from people’s interest in knitting for personal purposes to knitting with an entrepreneurial form of conservation, turning animals into economic commodities.

From an ABC perspective, the knitting for conservation project seemed inclusive, culturally sensitive, and bottom-up, endorsing local meanings of knitting, entrepreneurship and conservation and offering an alternative source of income to improve indigenous people’s livelihoods. However, a focus on practices revealed how the intervention, unintentionally, reinterpreted conservation values through new ways of knitting to better align with neoliberal conservation aims (see also Stronza & Gordillo, 2008). In other words, our findings reaffirm broader debates that argue that conservation projects (too often) replicate neoliberal conservation policies and practices (Fletcher, 2015; Fletcher & Neves, 2012; Turnhout et al., 2013; Tang & Gavin, 2016) through individual-centred attitude and behavioural change approaches (Hampton & Adams, 2018). Projects such as the knitting for conservation initiative that we discuss here essentially combine neoliberal values with sustainable conservation and social efforts and, thus, duplicate dominant systems found in local and international policies and institutions. By so doing, they also create (intentionally or unintentionally) a disconnect between already existing local know-how and relationships between individuals and their surrounding biodiversity, instead of achieving the intended sustainable conservation connection.

Concretely, by focusing on shifting meanings, we were able to highlight that through the knitting workshops, participants adopted external concepts related to the IUCN “red list”, institutional research findings, and conservation policies promoted by a national conservation communication campaign to increase the sale of the knitted animals to tourists. Matching tourists’ external ‘right way’ of doing conservation and involving them in conservation efforts by buying the knitted animals did not create a conservation relationship or connection with the local animals. On the contrary, it turned animals into a commodity to be sold.

Our focus on material shifts further affirmed that the knitting for conservation program that meant to conserve a natural environment created the opposite. By introducing wool and crochet, the new knitting practice generated a disconnect with natural materials (e.g. bromelias, pita, and seeds). People were rapidly adopting and substituting natural materials with synthetic materials. This could make people think that they are contributing to conservation efforts, but actually, community members are devaluing the use of their own natural materials available around them and responding to environmental changes as they seek to find alternative ways to sustain their practices (e.g. since natural resources for knitting hammocks and shigras are declining, they are looking for alternative materials that will last longer).

Finally, a focus on shifting skills showed that participants had a great interest in the knitting project when the social-entrepreneurship aspect started to flourish, an aspect that had already become more common through eco-tourism associations that came up with the establishment of the Biological Reserve. However, the knitting project influenced participants in adopting socio-economic systems that were unfamiliar to them. For example, the project did not recognize community-organized economic management systems and aimed to bring new ways of managing income. The knitting project created an argument for shifting knitting into the economic market for tourists, thus, encouraging an explicitly neoliberal meaning of conservation. This has also endangered the sustainability of the programme itself: after having successfully sold knitted products, finding access to financial resources and materials remained difficult.

Hence, our research furthers critiques of social innovation and eco-tourism ventures as pathways to sustainable conservation. Researchers such as Fletcher et al. (2015), Lisetchi and Brancu (2014), Turnhout et al. (2013) and Wunder (2000) argue that neoliberal conservation policies and practices, supported by institutions, tend to replicate the very processes of neoliberal approaches to the environment and economic well-being that have led to biodiversity loss/need for conservation in the first place. Similarly by continuing to impose 'top-down' visions for conservation and tourism under the guise of inadequately implemented 'participatory' approaches, the knitting workshops entrenched the neoliberal model further without substantive reflection on local, indigenous perspectives on human–environment relations. In other words, as social innovation and neoliberal conservation initative, the knitting workshops, at least as they were conceived and implemented during Maria Cristina’s involvement with them, entailed the potential to undermine rather than strengthen long-term environmental sustainability.

A focus on shifting elements also highlighted that the knitting project added previously non-existing challenges to community members by missing various aspects of local know-how, understandings, and use of tools and technologies. Examples include travelling to town, buying synthetic materials, and adopting new economic systems which made the adoption of new practices less sustainable. The knitting for conservation project, furthermore, shifted gender roles, people’s interest from wanting to knit gloves, carrier bags and hats, which is something they wanted for themselves, to knitting animals that participants associated with bad luck with the intention to ‘protect’ them and sell them to tourists. In other words, while the knitting for conservation project may have been able to shift conservation practices according to dominant neoliberal conservation paradigms, shifts in meanings, materials and skills undermined aspects of local culture, knowledge, and know-how which can better support project objectives to preserve biodiversity in the Ecuadorian Amazon through participatory engagement with Kichwa communities, and project sustainability. By so doing, the project contradicted the promise of more genuinely participatory approaches to conservation. As Gegeo and Watson-Gegeo (2002) demonstrate projects that support local initiatives without imposing external perspectives on, and approaches to, socio-economic well-being are more likely to be sustainable, and successful, in the long run.Footnote 9

7 Conclusions: reconfiguring perspectives for environmental sustainability

The knitting for conservation project answered to a combination of international and local governmental policies (e.g. education and environmental sustainability and conservation) and [Sumak] community engagement and environmental education strategies. We focused on the project’s conception period (2015–2018) and demonstrated how during this time these policies and strategies structured thinking and ways of doing things (e.g. ‘conservation’, ‘social-entrepreneurship/innovation’, ‘participation’) in a particular, externally determined ‘correct’ way. The SPT perspective takes culture, context, and history into consideration which allows for a better understanding of the dynamic processes taking place locally and, thus, uncovers some of the limitations embedded in the dominant ABC approaches to conservation.

A practice-based approach further reveals how the economic values of neoliberal conservation may lead to environmental changes and biodiversity loss and indicates how conservation and economic thinking have become entangled through [Sumak] projects. Policies, research findings, and community engagement strategies structured the program in a way that people were told to adhere to what conservationists and tourists want and to learn and adopt new behaviours and practices. If projects want to become sustainable, they should reflect on the difficulty that people have in adopting practices that they do not use and that create challenges in maintaining them and eventually do not work for them.

Using SPT to look at participatory approaches within SBCC interventions opens up new opportunities for evaluation and project intervention within the knitting and comparable programmes. It allowed for uncovering the various ways that ‘participatory’ SBCC approaches fall short of highlighting contextual forms of knowledge, of being inclusive and transformative (see also Hickey & Giles, 2013), and uncovering how participation continues to, knowingly or unknowingly, replicate top-down policies and structures that might be influencing people into doing things and saying things in a way that they are not used to (see also Mosse, 2001; Telleria, 2021; Turnhout et al., 2010).

This means that by focusing on practices and the shifts of materials, skills, and meanings project managers and policymakers can do a better job of developing a holistic intervention that can better consider culture, context, and history. By being careful not to structure ‘participation’ within predetermined problems and policies within a particular list of behaviours and attitudes, programs, institutions, and policies can better reflect, acknowledge and create relevant participatory settings that favour sustainable ways of life. Program organizers can also steer away from replicating particular policies and structures (e.g. combining conservation with economic systems) or provide alternatives that consider people’s cultural relationship with the entire ecosystem instead of side-lining them because they do not fit within a particular policy or strategy. Lastly, institutions can use SPT to develop projects and participatory settings that encourage participants to enhance their own know-how, use of tools and technology, and understandings in a way that can be sustainable and that better fit with people’s ways of living.

Data availability

The ‘raw data’ generated from this project will be made accessible to no one other than myself, in accordance with best practice in Anthropology as established, in the Netherlands, by the Wageningen University and Guidelines for Anthropological Research: Data Management, Ethics and Integrity, published on 30/7/2018 and written by Martijn de Koning, Birgit Meyer, Annelies Moors, Peter Pels.

Notes

For an additional reflection on the project by the other co-founder, Caroline Bacquet, see Bacquet-Pérez & Batres-Quevedo (2019).

Also known as Napo Runa or Kichua.

This is a pseudonym.

National Communication campaign: Alto al Tráfico Ilegal de Animales.

The yellow-spotted Amazon river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis), the Zimmermann's poison frog (Ranitomeya variabilis), and the Woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda).

The co-founder also has her own knitting workshop accounts as she worked with [Sumak] students and other local communities (Bacquet-Pérez & Batres-Quevedo, 2019).

The knitting for conservation project was recognized by its innovative (entrepreneurship), conservation and intercultural value (fourth place) by the United Nations Alliance of Civilization and the Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW) Group Intercultural Innovation Award. Maria Cristina was no longer involved in the project after the award was received, thus this paper does not reflect the analysis of this stage.

Also known as Aquatic coral snake and in kichwa language, manduru machacuy.

Since Maria Cristina’s involvement, the project has evolved further. Most substantively, the initiative is no longer run by [Sumak] and has instead become an independent association. This shift may have led to additional shifts in meanings, materials and skills and potentially addressed some of the shortcomings of the top-down approach that characterized the knitting workshops at their inception. Further research is needed to better understand these more recent shifts and their consequences for the initiative, the involved communities and environmental conservation in the area.

References

Andy Alvarado, P., Calapucha Andy, C., Calapucha Cerda, L., López Shiguango, H., Shiguango Calapucha, K., & Tanguila Andy, A. (2012). Sabiduría de la Cultura Kichwa de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana. In Segunda parte: Area de estudios socioculturales (First, Vol. 2, Issue 9). Univerisdad de Cuenca.

Arts, B., Behagel, J., van Bommel, S., & de Knoning, J. (2013). Forest and nature governance: A practice based approach. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5113-2

Bacquet-Pérez, C. N. O., & Batres-Quevedo, J. A. (2019). Animales tejidos y educación ambiental en comunidades kichwas de Tena. Killkana Social, 3(2), 21–28.

Barranquero Carretero, A., & Sáez Baeza, C. (2017). Latin American critical epistemologies toward a biocentric turn in communication for social change: Communication from a good living perspective. Latin American Research Review, 52(3), 431–445.

Bilhaut, A.-G. (2016). Conversatorio «Miradas cruzadas en el bosque: cultura, derecho, protección». Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’études Andines, 45(45 (1)), 263–267. https://doi.org/10.4000/bifea.7974

Chicaiza-ortiz, C. (2022). Environmental management strategies in Kychwa communities of the Amazon of Ecuador. May. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6582205

Collins, P., & Gallinat, A. (2010). The ethnographic self as resource: An introduction. In A. Collins, P; Gallinat (Ed.), The ethnographic self as resource: Writing memory and experience into ethnography (pp. 1–261). Berghahn Books.

Davidov, V. (2013). Historical foundations and contemporary dimensions of kichwa ecotourism. In Ecotourism and cultural production (p. pp 17–43). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137355386_2

Etzkowitz, H. (2002). Incubation of incubators: Innovation as a triple helix of university-industry-government networks. Science and Public Policy, 29(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/05390184030423002

Filius, J., Hoek, Y., Jarrín-V, P., & Hooft, P. (2020). Wildlife roadkill patterns in a fragmented landscape of the Western Amazon. Ecology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6394

Fletcher, R. (2015). Nature is a nice place to save but I wouldn’t want to live there: Environmental education and the ecotourist gaze. Environmental Education Research, 21(3), 338–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.993930

Fletcher, R., Dressler, W., & Büscher, B. (2015). NatureTM Inc.: Nature as neoliberal capitalist imaginary. In R. L. Bryant (Ed.), The internatinal handbook of political ecology (pp. 359–372). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857936172

Fletcher, R., & Neves, K. (2012). Contradictions in tourism: The promise and pitfalls of ecotourism as a manifold capitalist fix. Environment and Society, 3(1), 60–77. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2012.030105

Gaynor, N. (2014). The tyranny of participation revisited: International support to local governance in Burundi. Community Development Journal, 49(2), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bst031

Gegeo, D. W., & Watson-Gegeo, K. A. (2002). Whose knowledge? Epistemological collisions in Solomon Islands community development. Contemporary Pacific, 14(2), 377–409. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2002.0046

Halkier, B., Katz-Gerro, T., & Martens, L. (2011). Applying practice theory to the study of consumption: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Journal of Consumer Culture, 11(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540510391765

Hampton, S., & Adams, R. (2018). Behavioural economics vs social practice theory: Perspectives from inside the United Kingdom government. Energy Research & Social Science, 46(July), 214–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.07.023

Hickey, S., & Giles, M. (2013). Towards participation as transformation: critical themes and challenges. In Participation: From tyranny to transformation? Exploring new approaches to participation in development (pp. 1–284).

Hobbis, G. (2020). The digitizing family: An ethnography of melanesian smartphones. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34929-5

Hornung-Leoni, C. T. (2011). Progress on ethnobotanical uses of Bromeliaceae in Latin America. Boletin Latinoamericano y Del Caribe De Plantas Medicinales y Aromaticas, 10(4), 297–314.

Kiik, L. (2018). Wilding the ethnography of conservation: Writing nature’s value and agency in. Anthropological Forum, 28(3), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2018.1476222

Koot, S. (2016). Perpetuating power through autoethnography: My research unawareness and memories of paternalism among the indigenous Hai//om in Namibia. Critical Arts, 30(6), 840–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1263217

Lennie, J., & Tacchi, J. (2013). Introduction. In Evaluating communication for development: A framework for social change (1st ed., pp. 1–20). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203078495

Lisetchi, M., & Brancu, L. (2014). The entrepreneurship concept as a subject of social innovation. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 124, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.463

López Pazmiño, N., Gallegos, M. C., & Meneses Játiva, P. E. (2019). Formación de públicos en el cine ecuatoriano. Inventio, 15(35), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.30973/inventio/2019.15.35/7

Lyall, A., & Valdivia, G. (2019). The entanglements of oil extraction and sustainability in the ecuadorian Amazon. In Environment and sustainability in a globalizing world. London: Routledge.

Marcinek, A. A., & Hunt, C. A. (2015). Social capital , ecotourism , and empowerment in Shiripuno, Ecuador. International Journal for Tourism Anthropology, 4(4).

McKee, N., Becker-Benton, A., & Bockh, E. (2014). Social and behavior change communication. In The handbook of development communication and social change (pp. 278–297). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118505328.ch17

Moeller, N. I. (2018). Haphazard knowledge production: Thoughts on ethnography and mess in the urbanising Ecuadorian Amazon. In A. J. Plows (Ed.), Messy ethnographies in action (pp. 33–45). Vernon Press.

Moeller, N. I. (2020). Awakkuna: Knitting for conservation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. [Blog Post]. https://subsistencematters.net/talks/awakkuna-knitting-for-conservation-in-the-ecuadorian-amazon/

Mosse, D. (2001). “People’s knowledge”, participation and patronage: Operations and representations in rural development. In B. Cooke & U. Kothari (Eds.), Participation: The new tyranny? (pp. 16–25). Zed Books Ltd.

Ramirez Saldarriaga, J. (2016). The history of amigurumi. In Amigurumi (pp. 1–84). Aalto University.

Reckwitz, A. (2004). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. Practicing history: New directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn, 5(2), 245–263.

Schramm, W. (2006). What mass communication can do, and what it can “help” to do in international development. In A. Gumucio Dagron & T. Tufte (Eds.), Communication for social change anthology: Historical and contemporary readings (pp. 26–35).

Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environment and Planning A, 42(6), 1273–1285. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282

Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. Sage Publications.

Shove, E., & Walker, G. (2010). Governing transitions in the sustainability of everyday life. Research Policy, 39(4), 471–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.019

Stronza, A., & Gordillo, J. (2008). Community views of ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 448–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.01.002

Tang, R., & Gavin, M. C. (2016). A classification of threats to traditional ecological knowledge and conservation responses. Conservation and Society, 14(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.182799

Telleria, J. (2021). Development and participation: Whose participation? A critical analysis of the UNDP’s participatory research methods. European Journal of Development Research, 33(3), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00287-8

Tocancipá-Falla, J., Gualinga, L., León, H. F., Pardo-Enríquez, D., Nieto, S., & Vargas, S. (2018). Conocimientos, representaciones y cambio sociocultural. El caso de la asociación intercultural “Sinzchi Warmi”, Comunidad Ancestral Puerto Santa Ana, Provincia de Pastaza (Ecuador). Revista de Antropología Social, 27(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.5209/raso.59430

Tufte, T., & Mefalopulos, P. (2009). Participatory communication: A practical guide. World Bank.

Turnhout, E., Van Bommel, S., & Aarts, N. (2010). How participation creates citizens: Participatory governance as performative practice. Ecology and Society. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03701-150426

Turnhout, E., Waterton, C., Neves, K., & Buizer, M. (2013). Rethinking biodiversity: From goods and services to “living with.” Conservation Letters, 6(3), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00307.x

Uzendoski, M. (2005). The Napo Runa of the Amazonian Ecuador. University of Illinois Press.

Watson, M. (2016). Placing power in practice theory. The Nexus of Practices: Connections, Constellations, Practitioners, December 2016, 169–182. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315560816

Wise, G., & Carrazco Montalvo, I. (2018). How to build a regional university: A case study that addresses policy settings, academic excellence, innovation system impact and regional relevance. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 40(4), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1482104

Wise, G., Dickinson, C., Katan, T., & Gallegos, M. C. (2020). Inclusive higher education governance: Managing stakeholders, strategy, structure and function. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1525698

Wunder, S. (2000). Ecotourism and economic incentives - An empirical approach. Ecological Economics, 32(3), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00119-6

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time and effort necessary to review the manuscript. We sincerely appreciate all valuable comments and suggestions. We are especially grateful to the eco-tourism associations, communities, and research assistants involved in the work.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The first author was employed by the institution organizing the knitting workshops at the time of her data collection. However, her research was conducted independently from the institution, during her free time, and using her personal funds. Research participants were aware of her employment situation and provided informed consent. At the time of writing and data analysis, the first author was no longer employed by the institution. The first and fourth author are on the board of directors of the non-profit organization that helped facilitate the qualitative research. They receive no compensation as members of the board of directors. The second and third authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Ethics statement

This research complies with the ethics guidelines of Wageningen University & Research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gallegos, M.C., Buizer, M., Hobbis, S.K. et al. Knitting for conservation: a social practice perspective on a social and behaviour change communication intervention. Environ Dev Sustain 26, 8687–8707 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03066-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03066-7