Abstract

We analyze 15 German cartels, focusing on the personal characteristics of the individual participants, the methods and frequency of communication as well as the internal organizational structures within the cartels and their eventual breakup. Our results indicate that cartel members are highly homogeneous and often rely on existing networks within the industry, such as trade associations. Most impressively, only two of the 158 individuals involved in these 15 cartels were female, suggesting that gender plays a role for cartel formation. We further identify various forms of communication and divisions of responsibilities and show that leniency programs are a powerful tool in breaking up cartels. Based on these results we discuss implications for competition policy and further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The prospect of increased market power and profits has motivated collusion and cartel formation for more than a century. As cartels inflict substantial economic damages (see, e.g., Connor, 2014) they have been strictly regulated by competition law and subject to prosecution and severe fines in most jurisdictions for quite some time—the EU alone has imposed over 31 billion Euros in fines since 1990 (European Commission, 2022). And yet, collusion still flourishes. The prevalence of cartels has inspired a large body of empirical and theoretical literature that has identified several determinants of the formation and stability of collusive agreements including industry and market structure, firm and demand characteristics, as well as antitrust law and the macroeconomic environment (e.g., Levenstein & Suslow, 2011, 2006a, Connor & Bolotova, 2006, Feuerstein, 2005).

In the majority of this literature firms are regarded as collective entities with one objective function and the formation and breakdown of cartels are typically explained by the firms’ incentives and corresponding market conditions. The internal organization of cartels is usually treated as a “black box” (Baker & Faulkner, 1993). While this approach has provided valuable insights, it disregards one crucial aspect: Cartels are typically formed by individuals and the stability and persistence are essentially problems of trust between real people. In a stylized way, cartels can be illustrated as Prisoners’ Dilemma where cooperation or collusion can increase both player’s profits, but there are strong incentives to deviate (see, e.g., Tullock, 1985). As cartel agreements cannot be based on enforceable contracts, members always face this risk of deviation, for example through cheating or being reported to competition authorities. In order to overcome this dilemma, cartel members need to develop internal structures that allow them to establish trust and ensure cooperation. Only then, they will be able to maintain a cartel sometimes for years or even decades despite the inherent risks. Put differently, the establishment and maintenance of trust between cartel members are of utmost importance for the functioning of a cartel.

Interestingly and rather surprisingly, the social structures between individual cartel members have only scarcely been analyzed so far and much remains unknown about the particular characteristics of cartelists and how they manage to maintain trust and cooperation. There are a few notable exceptions though, such as Leslie (2003), who discusses several determinants of trust relevant for the establishment and maintenance of collusive agreements and applies them to examples from historical cartels. In more recent research, Jaspers (2017, 2020) identifies the coordination mechanisms of 14 Dutch cartels focusing on the social structures that create trust between cartel members. An analysis of the social organization within recent French cartels conducted by Abate and Brunelle (2022) confirms the relationship between informal industry networks and anti-competitive conduct. Other papers focus on specific cartels or industries, such as Podolny and Scott Morton (1999) who examine how the social status of an entrant firm affected the behavior of firms involved in the historical British shipping cartels, or Baker and Faulkner (1993) who analyze the communication networks of three cartels in the heavy electrical industry in the 1950s. Van Driel (2000) addresses the non-economic factors involved in the formation and persistence of collusion as well focusing on the social conditions and characteristics of executives in four different Dutch shipping markets. In addition, Harrington (2006) has elaborated on the role of organizational structure, allocation of tasks, and communication in cartels.

This research is complemented by controlled laboratory experiments where players simulate firms. The way individuals behave when confronted with the opportunity to collude in the laboratory and the conditions under which they overcome the incentive to defect can help in identifying the mechanisms behind cartel stability. These studies have provided insights on the role of personal characteristics, such as gender, preferences and cultural background, as well as communication, group identity and composition and deterrence policies (see, e.g., Haucap et al., 2022, Boulu-Reshef & Monnier-Schlumberger, 2019, Fonseca & Normann, 2012, Sally, 1995, Cox et al., 1991).

While laboratory experiments allow for the analysis of individual behavior, they cannot capture the complex incentives and motives of firm employees who interact for a longer period of time and who face real-life penalties, including non-monetary sanctions. In general, the sociology of cartels remains an understudied field.

Our paper uses data from 15 German cartels discovered in various industries during the past 20 years to analyze the personal characteristics of cartel members, their methods of communicating and the organizational structure of the cartels, as well as conflicts and the eventual breakup. The results complement the classical analysis of cartel stability and may help to inform both competition law enforcement and advocacy, but also inform the design of compliance programs. In providing additional insights on the inner workings of cartels, this paper may also advise the design of policies to prevent cartel formation in the first place. As our analysis is rather descriptive and highly explorative in nature, we do not want to overly stress any recommendations for public policy. Still, our finding that individual cartelists appear to be somewhat homogeneous and often rely on existing (personal) networks may suggest that cartels could be more likely in industries with homogeneous management groups than in those with more diverse groups of senior executives. Should this prove to be correct in further studies, there may be a “collateral benefit” of management diversity policies for consumers as it might reduce the likelihood of cartel formation among firms.

2 Data and methodology

This study is based on an in depth analysis of 15 cartels that operated in Germany and were fined by the Federal Cartel Office (FCO, in German “Bundeskartellamt”) over the last 20 years. The cases were selected in cooperation with the FCO and vary in the type and duration of the conduct, the number of participating firms and individuals and the industry.Footnote 1 The cases were selected after initial discussions with the Federal Cartel Office (FCO). As the information gathering from the FCO’s internal files involved additional work for the authority, we had to limit ourselves to 15 cases. In order to achieve a higher degree of comparability, we only included horizontal cartel agreements. We focus on cases where the FCO’s files contained more detailed information about the individuals involved and the inner working mechanisms of the cartel, as the amount and quality of information in the FCO’s files is rather heterogeneous in this respect. We also tried to find a rather diverse mix of industries, so as to not only study one particular industry.

The first data source are information provided by the FCO. After a collusive agreement was discovered in an investigation, the authority issues fine notices, which contain some information on the personal characteristics of the participants, their involvement in the cartel as well as a description of the inner workings of the cartel. For data protection reasons these documents are not public though.Footnote 2 In order to access this data while ruling out inference about participants’ identities, the FCO has aggregated the information from the confidential notices for this study based on a list of variables which was developed by the authors and modified by the FCO according to the information that was available (see Appendix for the variable list). The results from this analysis are presented in the first parts of each of the following chapters as cartel statistics.

This quantitative analysis is complemented by qualitative data from publicly available case reports and press releases published by the FCO that summarize basic information on the infringement and participants and the verdicts published after a case has been tried in court. If a company or individual does not accept the fine they can appeal to the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht Düsseldorf, OLG). The verdicts from the trials are usually published and include information on the market structure, the way the cartel was established and operated, as well as characteristics of the firms and in some cases individuals, based on statements from witnesses and experts. These documents vary in length and detail depending on the nature of the verdict and the number of plaintiffs and provide an additional insight on the modus operandi of the cartels. Six of the 15 cases in our sample were subject to an appeal. Finally, verdicts from civil lawsuits filed by potentially damaged customers or—as in one case—by a firm against one of their managers who engaged in anti-competitive misconduct were added to the analysis. The documentation of individual cases was analyzed based on the variable list used by the FCO and is summarized in the second part of each chapter to provide deeper insights to the inner workings of the 15 cartels.Footnote 3

Table 1 provides an overview of the 15 cases and lists the number of entities involved in the cartels, the duration in years, the industry, the type of conduct and whether there was an application for leniency before or during the investigation. The continued table furthermore lists the main documentation on the cartel from the FCO and, in the respective cases, the court case numbers are provided. The number of participating entities ranges from three to 24, though in some cases this does not reflect all participants or those who were eventually fined. In the Flour cartel, for example, the competition authority discovered 60 companies involved in the agreement, but the prosecution was limited to 24 firms due to resource constraints (FCO, B11-13/06). In other cases, companies were exempt from fines because they took part in the leniency program and contributed to uncovering the cartel. Leniency applications were submitted in eleven cases, ten of which initiated the investigation. Additionally, in some cases legal entities other than firms participated in the cartel, such as industry associations. The data shown in Table 1 contains all parties prosecuted in the course of the competition authority’s cartel investigation and listed in the public case reports. The duration of the collusive agreements ranges from one year to twelve years with an average of 5.4 years (\(sd=3.9\)). This is in line with international studies that estimate average cartel duration between five and eight years (Levenstein & Suslow, 2011, 2006a). It should be noted that the duration refers to the time period that was proven in the investigation which does not rule out a longer total duration of the collusive agreements. Possible cartel history before the proven conduct is estimated at more than ten years in one case and at least one to six years in seven cases in the aggregated data provided by the Federal Cartel Office.

The majority of cartels in this sample concern construction and the manufacture and processing of materials, such as building materials and metals, followed by processed food. The propensity to cartelization in these industries has been found in other studies as well (Levenstein & Suslow, 2011; Bolotova et al., 2006). The last column lists the type of agreement. This study focuses on so-called “hard core” cartels, which are agreements between competitors aimed at fixing prices or quantities, submitting collusive tenders (bid rigging) or dividing markets. The main infringement is price fixing followed by the restriction of output. This finding is in line with other studies, such as Harrington (2006), who also notes that the most common collusive outcome is characterized by price and supply agreements.

It needs to be noted that our study potentially suffers from a selection bias. The cartels analyzed in this paper have been discovered by the authorities, which might be due to less effective concealment mechanisms or generally lower efficiency compared to cartels that persist and remain undiscovered. The cases analyzed may thus not be representative for the entire cartel population. Empirical research on undiscovered cartels is close to impossible though.Footnote 4 While we cannot rule out that participants in undiscovered cartels have different socio-demographic characteristics than the ones we have studied, we believe that our study already provides valuable insights into the types of individual cartel participants and it provides a starting point for further research on these characteristics.

3 Individual participants

The data provided by the FCO and the court verdicts offer a structural insight to the demographic characteristics of the individual cartel members. In total, 158 individuals were identified and prosecuted as participants of the 15 cartels in this sample. The number of participants depends on how many firms were involved. On average, one or two individuals per firm were associated with a cartel. The following section provides an overview of their gender, age, occupational position and duration of activity in the industry and firm.

3.1 Cartel statistics

As shown in Table 2, the gender distribution in this sample is very clear: Of the 158 individual participants, only two (!) are female. This is in line with results from international cartels, where less than five percent of the executives prosecuted for anti-competitive misconduct were women (Santacreu-Vasut & Pike, 2019) as well as French cartels from the last twelve years, in which only 1.6 percent of the core members were female (Abate & Brunelle, 2022). The low presence of women in cartels is also consistent with studies on corruption and corporate crime which indicate that women are rarely part of conspiracy groups and if so, usually take on minor roles (Decarolis et al., 2023; Steffensmeier et al., 2013). One reason for these results might be differences in the propensity to collude. The evidence is mixed though and behavior strongly depends on the choice environment, such as the associated risk and the frequency of interaction (see, e.g., Mengel, 2018; Balliet et al., 2011). However, in complementary research (Haucap et al., 2022) the authors have analyzed gender differences in a laboratory experiment where individuals could cooperate at the cost of an external third party (e.g., two firms colluding at the expense of consumers). The results showed that female participants were less likely to cooperate than male participants when cooperation caused harm to outsiders.

Another reason is an under-representation of women in positions that offer the opportunity to participate in a cartel (Dodge, 2016; Goetz, 2007). In order to reach and maintain a collusive agreement, participants need to have substantial autonomy and decision rights, for example in pricing policies, sales or even production. This is in line with (Levenstein & Suslow, 2006b), who find that it was typically the top executives who agreed on the initial terms of a cartel. Managers who do not occupy such positions are unlikely to engage in cartels. The majority of individuals (\(n=120\)) in our sample were indeed part of upper hierarchy levels in their companies and were either owners, managing directors or other senior executives. The exact positions of the cartel participants vary with regard to firm type and size. A number of firms are medium-sized businesses in which the owners are part of everyday business. In other cases, the participants were employees of multinational firms or other publicly listed companies. These companies usually have a larger number of hierarchy levels and departments that are managed by one or more executives. In this sample, the majority of cartel participants were heads of departments (often sales) or sales managers, legal representatives of their respective firms or board members.

As such positions are usually only reached after several years of experience, most of the participants (\(n=93\)) were 45–60 years old at the time the prosecution started, 28 were older than 60 years and only 20 participants were younger than 45. This corresponds to the duration of activity in the industry or firm, which was over ten years in 90 cases, five to ten years in ten cases and less than five for six individuals. Lastly, 126 people were born and living in Germany while only six people were living abroad.

3.1.1 Homogeneity and group affiliation

The demographic analysis indicates a high level of homogeneity between the cartel members. Almost all of the individuals are male, older than 45, born in Germany, who have been working in the industry or firm for more than ten years and hold high level positions. While this homogeneity partly stems from the overall structure within the labor force, it cannot fully be explained by it—especially regarding the gender distribution. On average, women occupy 27 percent of the top management positions in Germany’s private sector with the construction and manufacturing industry scoring lowest (11 and 16 percent) and the healthcare and retailing sectors scoring highest (55 and 40 percent) (Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, 2019). While this is still an under-representation of women in the management of firms, it exceeds the share of female cartel participants in this sample which is only 1.3 percent. The homogeneous composition of cartels is thus possibly not only a result of the demographic structure within the labor force, but it might rather be the particularly homogeneous networks that provide fertile ground for anti-competitive agreements. Furthermore, when looking for potential business partners (or accomplices), cartel members likely favor individuals who they identify with (see, e.g., Matsa & Miller, 2011; Akerlof & Kranton, 2000; Regarding the role of shared cultural and geographical background in cartels, see also Connor, 2007, 1997).

In order for an executive to initiate anti-competitive behavior, he or she needs to be confident that such proposals are met with approval and that the agreements will be upheld later on. Shared similar fundamental characteristics, such as age, race, gender and social status positively affect the beliefs and expectations about one another by creating a sense of group affiliation which in turn creates trust (McAllister, 1995; Turner et al., 1987). Trust remains crucial after a cartel is established as members are constantly subject to risks for which they cannot rely on legally binding contracts, such as deviation from agreements by other members, or reporting to the authorities. Only if cartelists expect each other to cooperate continuously, they will uphold collusive agreements, which again emphasizes the role of homogeneity for cartel formation and stability.

Group affiliation is further fostered if individuals have repeatedly interacted in the past and have created personal ties to each other which increases familiarity and positive expectations. Such networks can provide a strong foundation for cartel formation. They further stabilize established agreements by increasing the costs of cheating or exit: If a member decides to deviate or report a cartel, they face the risk of being excluded from their network or weakening their personal bonds within the firm or industry (see also Leslie, 2003; Spar, 1994). The mostly long activity in the industry in this sample supports this notion, as it created several opportunities to meet repeatedly in some cases, for example within industry associations, and create the bonds which then provided a foundation to form collusive agreements.

3.2 Individual cases

The central role of personal ties for cartel formation is illustrated in the verdicts from the appeals to the Higher Regional Court (OLG). A detailed analysis of the individual cases shows how regular exchanges between firm representatives paved the way for anti-competitive agreements and provides insights into the rationale for the misconduct as well as examples on how a group identity was created between cartel members.

3.2.1 Personal relationships

In the majority of cases, cartel members were already well familiar with each other before the agreement started and knew each other from shared work within trade associations or meetings at fairs and conventions. In the Beer cartel, for example, the participants met regularly on several occasions before the cartel was formed. Additionally, they were all high-ranking executives who had similar positions and responsibilities in their firms, which created trust and a general willingness to talk. These executives often complained to each other about the market conditions and while, at first, it was just “general lamentation”, it eventually led them to coordinate their market behavior:

There were a large number of organized meetings such as fairs or conferences which provided the opportunity to talk about the omnipresent topic of prices.[...] People were friendly with each other [...] and were open to conversation.Footnote 5

The credibility [of the exchanged information] was based on the attendees’ mutual trust that they could rely on each other’s word within this circle of executive decision makers (OLG, V-4 Kart 2/16).

Personal relationships were also maintained in the Roasted coffee cartel and the Wallpaper cartel, where meetings of the trade association and the care of shared customers brought the firm representatives together and allowed them to get to know each other and share their opinions, which eventually led to collusion and facilitated the implementation of agreements:

Within the management circles of the producers, contacts in person or over the phone were common. These had the purpose of introducing new members or to coordinate the activity in the trade association. In addition, the members of the lower management level occasionally met on fairs or at client meetings (OLG, V-4 Kart 5/11).

The individuals knew each other well and worked together confidently. They had extensive communication via phone and in person due to the care of shared customers. [...] They could rely on each other to implement the strategies they commonly decided on (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

3.2.2 History of cooperation

Apart from regular interaction within trade associations or customer care, in some cases networks had developed as part of a history of coordinated behavior. The aforementioned Wallpaper cartel, for example, took place in an industry where producers had established two legal cartels in the 1950s.Footnote 6 Even though the agreements were officially terminated in the 1980s, they were resumed in various firms shortly after (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17). Such legal arrangements can create a common mindset in the industry, and allow participants to establish the networks and methods necessary to coordinate behavior beyond the permitted agreements. This is also illustrated in the documentation of the Sweets cartel, in which the Federal Cartel Office had authorized a so-called condition cartel that allowed firms to share the general conditions of their business starting in 1970. The members, however, felt that the development of this cartel was exhausted and started to discuss topics that were not covered by the cartel permission:

[...] It is assumed that the condition cartel had created closeness and a sense of solidarity between its members [...], which is why there was only a low inhibition threshold of crossing its legal limits (OLG, V-4 Kart 6/15).

This legal cartel created a “cultivated atmosphere and trustful cooperation” in the form of regular information exchanges, which were gradually extended to topics that were not covered by the approval of the FCO.

3.2.3 Motivation for agreements

In the aforementioned case, the development was motivated by the challenges the participants faced regarding the opposing market side, which created a sense of solidarity and strengthened their bonds. This observation applies to several other cases in our sample and was typically induced by an increase in market and bargaining power of the retailing industry through which producers often sell their products (Bundeskartellamt, 2014).Footnote 7 The firms of the Sweets cartel, whose profits mainly depended on these sales, were weakened in their bargaining position and felt extorted:

A witness stated that once a year, producers were invited by the retailers to attend the “extortioner-circle”. This notion was shared by another witness, who described how retailers extorted the producers each year [in the negotiations] (OLG, V-4 Kart 6/15).

As a consequence, the sales managers of the firms felt as part of a “community of destiny” with a common adversary, who had to “compensate their disadvantages through an advance in knowledge” (OLG, V-4 Kart 6/15). The pressure induced by the powerful retail firms created a sense of unity in the Beer cartel and the Roasted coffee cartel as well. In both cases, the executives of the corresponding firms felt trapped between the demands of the retailers which were aggravated by increasing input prices and the risks of losses in market shares by unilaterally changing prices:

The [participants] had a sense of solidarity as they were all affected and unified in the tension between economic pressure to increase prices and the paralyzing risks of solo action (OLG, V-4 Kart 2/16).

The tension between the price change of raw materials and the competitive pressure of retail companies demanded the participants to pull together [...] in order to hold their ground in the market (OLG, V-4 Kart 5/11).

In order to mitigate this pressure, the individuals started to share confidential information on firm data and the contents of the yearly negotiations with the retailing firms. As the negotiations are typically conducted without knowledge of the competitors’ conditions, sharing information eliminated the uncertainty of firms and allowed them to coordinate market behavior.

3.2.4 Group identity

The sense of partnership and unity was also expressed in the way cartel participants addressed each other, such as “business partners” (Roasted coffee cartel), “colleagues” (Beer cartel) or “friends” (Rails cartel). Furthermore, the documentation reveals that several cartels had created a distinct identity by giving themselves a name. Studies have shown that such an identity can increase cooperation as it strengthens the feeling of “being a member of the club” which in turn can positively affect expectations about others as well as empathy and cooperative behavior (Goette et al., 2012; Leslie, 2003). In this sample, the members of six cartels had named themselves. This could be an acronym of the corresponding company names (Spectacle lenses cartel), labels for different sub-groups (such as upper and lower table in the Cement cartel) or a simple nickname (Rails cartel).Footnote 8

4 Communication

One central prerequisite of cartel formation and persistence is communication. Communication serves several purposes: Before a cartel is formed, potential participants need to signal their willingness to collude, find partners and then develop and negotiate the terms of the agreement. After the cartel is established, participants may need to exchange information in order to monitor each other and enforce adherence. If a member did cheat on the terms, communication can be used for conflict resolution and prevent cartel breakup. Furthermore, the environment in which cartels operate is not always constant but can be subject to exogenous changes to which members often need to adapt. Communication is usually necessary to discuss and implement these changes in terms.

Besides these organizational purposes, communication plays a significant role in maintaining cartel stability by fostering trust. When individuals talk to each other, they can signal the willingness to cooperate and increase familiarity with each other. This reduces the uncertainty and creates positive expectations. If cartel members trust each other to cooperate and identify with them, the incentives to deviate are mitigated and the agreement is stabilized (Leslie, 2003). A positive impact of communication on cartel formation and stability has been reported in experimental studies, such as Fonseca and Normann (2012) or Cooper and Kühn (2014), as well as in empirical studies, such as Genesove and Mullin (2001) or Levenstein and Suslow (2006b).

While communication is crucial for cartel stability, it is constantly subject to the trade-off between efficiency and secrecy. If the information exchange between cartel members is inaccurate, coordinated market behavior is more difficult and disputes might arise, which can destabilize the cartel from the inside. Efficient and effective communication is crucial to reach agreements, monitor their implementation and adapt to changing circumstances. On the other hand, these information exchanges need to be concealed from outsiders, such as competitors who are not part of the cartel, customers and competition agencies to reduce the risk of being detected and destabilized or prosecuted. Cartel members thus constantly need to ensure secrecy while maximizing the efficiency of their exchange (Baker & Faulkner, 1993). The literature has identified several methods in this regard, which range from code names and encrypted messages to meetings in the context of legal functions or on secret and remote sites to complex implementation strategies to divert suspicion (Leslie, 2021).

4.1 Cartel statistics

These methods were also used in our sample, as the data aggregated by the FCO shows. A general overview of the modes of communication is shown in Table 3.Footnote 9 All 15 cartels used different forms of communication, which varied in intensity depending on the type and duration of agreements. Personal meetings took place in each case and were held from three times or less in four cases up to 15 times a year in one case. The frequency of meetings varies within cases, as several cartels were split into sub-groups that were concerned with different topics and not all company representatives were present in all meetings. The meetings took place in several locations: In nine cases they were embedded in meetings of the industry association and were held in the same or adjacent premises; in eight cases participants met in the context of fairs, two cartels used firm premises and two groups used other locations such as hotels or restaurants. Phone calls were made in at least 14 cases. The exact number of calls is not determined, but in most cases, they were made regularly. The frequency varied with the phase of the cartel agreement, e.g., they were scheduled when a tender was close to being submitted. In one case, cartel members called each other daily, in other cases phone calls were made only a few times during the entire cartel period. In order to conceal their conversations, two cartels used designated prepaid phones or fake names when talking to each other. E-mail exchanges are documented for only seven cases, possibly to reduce traceability. The use of an encryption software is, however, only documented in one case. In another cartel, the members shared passwords for their firm intranet to access each others’ confidential information. Our data does not indicate that the frequency and mode of communication depends on the size or duration of the cartel. It rather depends on the type of agreement, and how often prices or other parameters were adjusted or tenders submitted.

4.2 Individual cases

The adaption of communication methods to different phases and requirements of the cartel is illustrated in the press releases from the FCO and the verdicts from the court appeals. In the majority of documented cases, major decisions such as agreeing on the general terms like the sales quotas or percentages of price increases were made in person. Based on these terms, the modalities of the implementation within the firms and the exchange of information took place via phone or e-mail. Deciding on the fundamentals of an agreement in person reduces the paper trail which might provide proof for the authorities. Furthermore, it is efficient and facilitates the establishment of trust. If the terms of an agreement are complex and require negotiation to account for the interests of all cartel members, face-to-face communication is more flexible and allows participants to react and adapt more quickly than bilateral phone calls or e-mails. In addition, in-person meetings allow to capture subtle cues, such as facial expressions, which can positively affect the expectations of cooperation and in turn build trust. Trust is further strengthened when people are gathered in one room to discuss confidential information, as it creates a sense of community.Footnote 10 After the members of a cartel have successfully signaled their willingness to participate and trust each other to comply with the terms they agreed upon, the final implementation and adjustments can be coordinated via phone or e-mail. These tasks are typically less complex and do not contain a “moral” component which alleviates the need for face-to-face communication (Frohlich & Oppenheimer, 1998). This procedure is also more efficient, as minor adjustments or coordination does not always concern all members of the cartel and can be resolved in smaller circles. Fewer in-person gatherings also reduce the visibility of a cartel and thus increase the level of concealment.

4.2.1 Communication levels and channels

The communication pattern just described was observed in the Beer cartel, for example. The general idea to increase prices was initially discussed between the brand leaders’ executives in person at a trade fair and, following a number of phone calls, the price increase was implemented in the market. Two years later, the firm representatives met again in person at an industry fair which offered the opportunity to update the agreement. A topic that had already been discussed in the past was a coordinated price increase for another product category. One marketing manager who was particularly keen on this extension took the opportunity and invited the other executives to a hotel close to the fair for an exchange. The official topic was inconspicuous and within legal bounds, but the conversation was intended to focus on prices:

From the start, the witness [i.e., the marketing manager] intended to address the supposedly urging question of another price increase, hoping for new stimuli towards coordinated actions. He informed [several] other participants of this plan (OLG, V-4 Kart 2/16).

The official topic was quickly dealt with and the conversation was steered towards prices by the aforementioned marketing manager, who asked each participant in turn about their stance and then proposed an open exchange of opinions and ideas. This exchange did not yield concrete results, however, and the firm representatives left the meeting with disappointment. The marketing manager still pursued the idea of extending the cartel agreement and called the director of sales and marketing of one of his competitors four months later. Together they decided to proceed based on a “division of labor” and contact the other firm representatives to “consequently promote” their plan. The price increase was implemented industry-wide in the beginning of the following year (OLG, V-4 Kart 2/16).

A similar procedure has been documented for the Wallpaper cartel, where the managing directors of the four largest producers in Germany met in person at an industry gathering. After the official part of the meeting was over, the conversation turned towards a possible coordinated price increase. This conversation did not result in a concrete plan, but was rather a confirmation for the participants that they all agreed on the necessity of coordinated behavior. The specific terms were then discussed internally within each firm and later between the corresponding sales managers. As these sales managers did not have the authority to implement a price increase, their conversation had the sole purpose of facilitating the final agreement between the managing directorsFootnote 11:

The exchange was meant to develop a plan for a coordinated price increase and inform their superiors, who planned to meet again [...] shortly after and wanted to reach a quick decision. The meeting furthermore enabled the sales managers to assure and encourage each other that they would follow through with the price increase (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

A few weeks later, the managing directors met again in person and, as the sales managers had already prepared the content of a potential agreement, no discussion was necessary and the price increase was agreed on. In the following weeks, the sales managers observed whether all competitors implemented the terms. As one sales manager did not fully comply, phone calls and e-mail exchanges took place, but the issue could not be resolved (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17). Two years later, an increase in input prices motivated the cartel members to coordinate another price increase, which was again prepared by the sales managers and two weeks later decided by the managing directors in a personal meeting:

One managing director asked the representatives of the major producers to gather in a separate room of the hotel [where an industry assembly took place] during a break of the official conference or after it was over [...] to present his firm’s reaction to the change in input prices. The indented price increase was approved by the other participants and viewed as a valid measure for their firms, which was expressed by approving nods or the lack of objection (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

The price increase was announced by the firms shortly after and implemented in the beginning of following year.

The combination of personal contacts and communication via phone and e-mail is also documented in the Spectacle lenses cartel. Over a period of eight years, the executives of the five leading companies had met regularly to agree on various competition parameters and inform each other about their strategies. These gatherings would take place three to four times a year and added up to at least 30 in total. Between meetings, cartel members exchanged e-mails in which they coordinated the specific information and strategies discussed in the personal meetings or scheduled upcoming events. Additionally, if a member could not participate in one of the meetings, he was called afterwards and informed about the results (FCO, B12-11/08).

Face-to-face communication was also valued in the Roasted coffee cartel, where managers and sales executives of the four largest companies met at least 20 times between 2000 and 2008. These meetings had the purpose of coordinating five price increases for several products. Numerous phone calls concerning the operational implementation of the terms discussed in person took place between these meetings. There was a clear assignment of who would call whom, according to the expertise and the responsibilities of the cartel members (FCO, B11-18/08; OLG, V-4 Kart 5/11). Members of the Rails cartel, who colluded in public and private tenders, also used different forms of communication and complemented their personal meetings with e-mails and phone calls. Bilateral exchanges via phone were the main coordination device and could take place daily if a tender was close to being submitted and the cartel participants needed to clarify who should win the contract (FCO, B12-16/12, B12-11/11).

4.2.2 Trade associations

In order to conceal personal meetings, cartel members often took advantage of their trade associations. These associations regularly host official events, where firm representatives have the opportunity to meet in person. In addition, some trade associations offer committees or work forces designated to specific topics such as marketing, sales or products. These circles meet regularly and give members the opportunity for a professional exchange. While this platform can benefit the industry, it is also at risk of being used for anti-competitive exchanges. If firm executives are used to sharing information and coordinating, for example, public statements or production processes, the reluctance to cross the fine line between legal and illegal information exchange is reduced and the meetings can become a platform for initiating and coordinating cartel agreements. These gatherings also provide a good cover for cartel meetings, as it does not raise suspicion when representatives of competing firms meet in one place and have conversations. Furthermore, such events are efficient, as the members travel to the location regardless of the cartel and do not have to undertake additional efforts to meet their colleagues (see also Leslie, 2021).

The use of trade associations as a platform for communication was observed in nine cases in our sample. A meeting of the trade association was the starting point of the agreement in the Clay roofing shingles cartel for example, where almost all firms in the industry had decided to increase prices for their products by issuing an “energy-price-surcharge” (FCO, B1-200/06). The executives of the 15 leading producers of the Drugstore product cartel were all members of a work force concerning a specific product field within the trade association. The group was founded in the 1990s, but by 2004 they used the five to six yearly meetings to exchange confidential and anti-competitive information which allowed them to coordinate their yearly negotiations with customers and their prices (FCO, B11-17/06). In the Rails cartel, a number of tenders were allocated at meetings of the working group on marketing, which was used as a platform for the cartel five to eight times per year from 2001 to 2008 (FCO, B12-16/12, B12-19/12). In the Wallpaper cartel, the managing directors who agreed on coordinated price increases were all executive board members of the German trade association and would benefit from board meetings to engage in anti-competitive exchanges as well (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17). The members of the Sweets cartel were organized in a committee of sales managers, which was closely linked to the federal trade association, and consisted only of higher-ranking managers to ensure competent contributions and a “trustful cooperation”. Between 2003 and 2008 the content of these meetings, which took place three to four times a year, turned to a systematic exchange of sensitive information on pricing strategies. This led to a change of the committee’s purpose from a general exchange in the interest of the association to a coordination between sales managers. The 20 meetings had a high level of organization and usually took place in hotels and within the premises of the trade association. They were thoroughly prepared by a lawyer who worked for the trade association at that time:

The chief executive of the association asked the members in the invitation to name topics for the agenda of the upcoming meeting. [...] The topics were adopted nearly word-for-word and sent out to the participants. In some cases, additional documents on market data, such as graphs on revenues and sales [...] which were provided by the firm representatives were distributed at the same time (V-4 Kart 6/15).

The agenda was then processed by having each participant comment on the topics in turn. As stated by one witness, each person tried to weigh in so as to be helpful for the community. If somebody did not have anything to say, they refrained from attending the meeting. Typical topics were the yearly negotiations with retailers, discounts and planned price increases.

4.2.3 Concealment of exchanges

Apart from the cover of legal industry meetings, cartel members made use of other methods to conceal their personal exchanges. Usually, the participants chose neutral places for their meetings, as, for example, in the Fire truck cartel, where the chief executives of four firms met 19 times between 2001 and 2009 at Zurich airport:

The venue in Zurich was chosen to conceal the meetings and to elude the German and European competition agencies (FCO, B12-11/09).Footnote 12

No written invites were sent out for the gatherings, and the participants refrained from drawing up agendas and lists of attendees. The date for the next meeting was usually set at the end of the current one. This indicates a high level of secrecy which the cartel members wanted to maintain. The main purpose of these meetings was to set sales quotas for each firm and monitor adherence with the agreement via lists containing current market statistics (FCO, B12-11/09). Meetings abroad also took place in an agreement of the Cement cartel, where cartelists moved their gatherings from Germany mostly to Zurich to “increase protection from cartel investigations” (OLG, VI-2a Kart 2-6/08). The members of the Roasted coffee cartel also valued secrecy and organized their gatherings accordingly. There were no written invitations for the 20 recorded meetings between 2000 and 2008. Instead, participants were invited via phone call, in some cases on short notice with no information on the purpose. The gatherings usually took place in airport hotels and were highly discrete:

From the outside, the meetings had a conspiratorial character. The rooms were only labeled with a company name that did not allow to draw conclusions about the true participants and the purpose of the meeting. There was no agenda, no list of attendees and no protocol (OLG, V-4 Kart 5/11).

A similar method is documented in the Spectacle lenses cartel, whose participants refrained from sending out invitations or writing down protocols or lists of attendees. The agendas were only made available on the meeting, for which the organization alternated between participants (FCO, B12-11/08; OLG, V-4 Kart 5/11).

The concealment of communication on other channels is documented for the Rails cartel, where members used burner phones and code words:

The defendant had ordered the purchase of “neutral phones” by a person who did not work for the company to ensure that the agreements between the sales managers could not be traced back to his firm (LAG, 12 SA 591/17).

As a cover, prices were sometimes communicated as stock prices or lottery numbers (FCO, B12-16/12, B12-19/12).

Code words were also used in a cartel connected to the Fire truck cartel:

To conceal conversations, the sales managers communicated via designated prepaid-phones. After the World Cup 2006, they used a “soccer language” which translated the intended discounts into match results (Bundeskartellamt, 2016).

4.2.4 Indirect communication

Communication is not limited to verbal exchange but can also be indirect, for example through documents that are exchanged between cartel members or posted publicly to inform individuals outside the company, such as suppliers or customers. This method has two advantages: It conceals cartel activity if there is no direct exchange between competitors and it serves as a signal of commitment to the other cartel participants (on the use of public announcements as a coordination device see also Harrington, 2022). This procedure was observed in several cases in our sample and would function as a signaling or monitoring device. After the members of the Roasted coffee cartel, for example, had agreed on the size and timing of the price increase for their main product, the participants exchanged price announcement letters with each other that were to be sent to the retail firms. The motive of this exchange was interpreted as a “mutual reassurance” and a “confidence-building” measure (OLG, V-4 Kart 5/11). Announcement letters were also exchanged in the Wallpaper cartel before they were distributed to the retailers. After the chief executives had agreed on a price increase, the sales and marketing manager of the brand leader shared the document with the other producers in the industry:

This meant to be a signal for the other firms, that the [brand leader] would in fact implement the price increase and assured the other executives to send out their own announcement letters that were drawn up in accordance with the agreement (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

In the following time, the other producers sent out their announcement letters which they also exchanged with each other. The exchange worked as a monitoring device to make sure that all members adhered to the terms they agreed on and showed “cartel discipline”. A public announcement was used as a signal in the Beer cartel as well. The chief executive of the brand leader was initially reluctant to implement a price increase and, therefore, refrained from the meeting between executives on the aforementioned industry fair. This caused caution within the other firm representatives, who were unsure whether a coordinated price increase was viable without the brand leader. In bilateral conversations, the chief executive was convinced though, which he signaled through an announcement in the industry press. This reassured his competitors to also implement the terms they had agreed upon (OLG, V-4 Kart 2/16).

Lastly, if cartel members knew each other well, communication became less important to coordinate and implement agreements. This is documented for the Rails cartel, which lasted at least ten years and allowed its members to develop a well-practiced system in which only a coordination of single projects rather than a general discussion of the agreement was necessary:

An established system had developed over the years, so that the rules of the game dispensed the need for case-by-case agreements for all projects (LG Dortmund, 8 O 19/16). Instead, the system was based on an understanding and mutual trust [between cartel members] across projects (FCO, B12-16/12, B12-19/12).

5 Organization

The development, implementation and adjustment of anti-competitive agreements is usually not straightforward but follows an internal cartel organization. Cartel members face different tasks which can be divided in sophisticated structures. These structures may be hierarchical so that higher and lower management levels are responsible for different stages or parts of the agreements. As Levenstein and Suslow (2006b) argue, such a structure allows cartelists to separate the communication and bargaining of the terms of an agreement from micro-level exchanges and activities. Especially in complex agreements, participants often assign different tasks to employees at different hierarchy levels—e.g., by separating the conclusion of the initial agreement from its execution, fine-tuning and information exchange (Leslie, 2022). Cartels can also be divided into sub-groups where topics and tasks are allocated according to each member’s area of expertise or regional market.Footnote 13 This division of responsibilities does not only increase the efficiency and flexibility of exchanges, but it can also help to conceal them from the outside. As argued by Baker and Faulkner (1993), decentralization reduces the exposure of cartel members and makes it harder for authorities to uncover the entire cartel. The organization between cartel members usually differs from the organization within traditional firms insofar as cartels are not governed by one central authority which allocates tasks, resolves disputes and aligns interests. Instead cartels are self-governed and members need to create their own rules and structures absent a central authority and a legal basis according to the characteristics of their respective agreements (Bertrand & Lumineau, 2016). The internal organization, therefore, varies between cases and strongly depends on the nature of the agreement. It is further affected by the duration of the cartel, as groups that engage for longer periods of time might be able to establish more sophisticated structures compared to short-lived cartels.

5.1 Cartel statistics

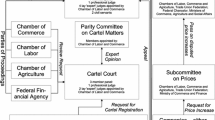

The 15 cases in our sample exhibit three main organizational structures: (i) a division of tasks between different hierarchy levels, which took place in ten cases, (ii) a geographical division, which is documented for two cases, and (iii) the use of an internal or external moderator in seven cases (see Table 4).Footnote 14

5.2 Individual cases

The specific implementation of these organizational structures is described in the individual case documents, which provide further insights on the methods of structuring cartels in order to adapt them to the internal and external environment in which they operate.

5.2.1 Hierarchical organization

Ten of the documented cartels were organized hierarchically, such as the East German part of the Cement cartel which consisted of the so-called “big four”, i.e., the four brand leaders in the region. This cartel was divided into two levels. The so-called “upper table” consisted of board members and general partners, who set sales quotas for each firm. These quantities were forwarded to management executives at lower levels of hierarchy to implement the agreement and to monitor the compliance of the cartel members. In order to do so, the sales managers developed a sophisticated calculation system, which they discussed at meetings of their so-called “lower table”. To improve the flow of information, one member of the “lower table” participated in meetings of the upper hierarchy level (OLG, VI-2a Kart 2-6/08). A division into two levels also took place in the Fire truck cartel. The higher level consisted of the top managers of the four largest manufacturers in Germany. At their yearly meetings, these managers discussed a comprehensive list of market statistics, fixed sales quotas and checked whether each firm adhered to their volume and price increases. A second group was formed between the sales managers of these firms, who coordinated individual tenders based on “project lists” which summarized municipalities, products and dates of the tenders that were to be submitted within the next months (FCO, B12-11/09). The members of the Rails cartel divided the coordination of public tenders in two levels as well:

The meetings of the management level were supposed to create transparency, reach a consensus and set minimum prices as well as discuss fundamental questions [...]. The targets set by the managers were specified and implemented on the lower operational level, who fine-tuned the prices and monitored the compliance with the target quotas (FCO, B12-11/11).

5.2.2 Geographical organization

A cartel division into sub-groups can also be organized geographically, as documented in the Flour cartel, where a total of 60 producers coordinated their prices, customers and quantities. The cartel operated in several “rounds of talk”, with one round being responsible for northern Germany, while the southwest was coordinated by smaller regional groups (FCO, B11-13/06). In order to increase efficiency by adapting general terms to the individual characteristics of different German markets, a regional division took place in the agreements of the Cement cartel concerning northern, western and southern Germany as well.Footnote 15 In a personal meeting, the representatives of the largest producers had decided to eliminate competition and agreed that a successful implementation of the cartel would require the majority of firms in the market to participate. Therefore, the industry leaders of each region were instructed to convince the remaining firms:

All participants were aware that everything else [besides the general agreement to coordinate the market] was to be arranged within the regions. The diverse market structures, especially the different market participants, the role of small and medium sized firms and different market leaders as well as previous cartels rendered it impossible to reach and monitor overarching agreements (OLG, VI-2a Kart 2-6/08).

5.2.3 Moderator

Another common feature of cartels in this sample is the use of a moderator, who would usually be a third party from outside the market. Such a “cartel secretary” can collect and process information and support cartel participants in the implementation and monitoring of terms. They can also stabilize trust, as the information is neutral and less likely to be distorted by individual motives. Lastly, the inclusion of a third party can increase secrecy, as the collection of information and the communication is detached from the cartel participants which reduces the risk of exposure. As described before, the members of the higher organizational level in the Fire truck cartel based their meetings on a comprehensive list of market statistics. This list was originally supposed to be drawn up by a German lawyer, but after the managers became concerned about its legality, a Swiss auditor was contacted who agreed to create an overview of data provided by the cartel members and organize meetings at Zurich airport to discuss these numbers (LG München, 37 O 6039/18). A neutral outsider was also involved in the Cement cartel, where data was stored on a Swiss notary’s computer (OLG, VI-2a Kart 2-6/08), and in the collusion on public tenders in the Rails cartel, which were coordinated by a clearing house based on an Excel file (FCO, B12-11/11).

The position of an independent administrator could be filled by employees of the trade associations, who in some cases actively took part in the cartels by centrally gathering and processing information and organizing meetings between cartel members. This happened in the Steel cartel and the Flour cartel, where a representative of the trade association attended the cartel meetings and supported the members in the coordination of their agreements. This participation resulted in a fine issued by the Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt, 2018; FCO, B11-13/06). An active involvement of the trade association was also uncovered and fined in the Wallpaper cartel. After the cartel members had personally agreed on a price increase, the industry leader X was to send out price announcement letters to the producers that did not participate in the meeting. This letter was drawn up by the chairman of the brand leader’s supervisory board immediately after the meeting and sent to the managing director of the trade association who forwarded it to the other producers. This procedure was efficient, as the trade association was in contact with the firms anyway, and concealed the central role of the brand leader:

This was advantageous for the [representative of X] as he could not be identified as the sender of a letter to his competitors. He knew that the distribution of price announcement letters was an indicator for illegal price agreements. [...] Early on he thus paid attention not to leave many written documents (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

Another participant of the meeting was not content with this procedure, however, and upset that they had given up on the consensus to leave the trade association out of the cartel. The managing director of the trade association was aware that he could not tolerate such agreements, but still took part in it (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

5.2.4 Dynamic structure

Lastly, the organization and moderation of a cartel can be dynamic and change between members, as documented in the agreement on private tenders of the Rails cartel. The market was allocated based on regular customers, who were not approached by other cartel members. The company that was supposed to win a contract coordinated the tendering procedure as a so-called “team captain”, by informing the other cartelists on what prices they needed to submit their bids in order not to be considered for the contracts. This role would alternate between cartel members depending on the customer who would invite a tender and the firm the contract was secretly assigned to (FCO, B12-16/12, B12-19/12).

6 Conflicts and breakup

Even though cartel members manage to develop trust and implement sophisticated organizational structures, they will eventually break up—some after months, others after decades.Footnote 16 Besides the external risk of being detected, cartel stability is constantly subject to internal risks. These can range from conflicts between members to deviation from agreements if a cartel member does not agree with the terms or expects an increase in profits, for example. Such disruptions do not necessarily cause a cartel to break up; in fact some cartels would develop various strategies to prevent the return to competitive conditions (Genesove & Mullin, 2001; Levenstein & Suslow, 2011). These conflicts can, however, undermine the trust between cartelists crucial for cartel stability and, in turn, impede their cooperation.

The biggest threat to cartel stability comes from leniency programs though, which give cartel members an incentive to report their infringement to the authorities by granting reductions in fines. An application for leniency not only terminates the agreement, but the mere option already undermines trust by creating the fear of being betrayed, thereby destabilizing existing cartels as well as preventing them in the first place (Bigoni et al., 2015; Leslie, 2003).Footnote 17 In Germany, the leniency program was introduced in 2000. It offers a reduction in fines or full immunity if a cartel is reported and the FCO is assisted in their investigation. In fact, after its introduction, the leniency program was used frequently by German cartel members: A total of 658 leniency applications were submitted between 2001 and 2016 (Bundeskartellamt, 2016).Footnote 18

6.1 Cartel statistics

Our sample supports the view that leniency programs are important for cartel termination and detection. In eight cases, the cartel broke down after a member had applied for leniency, two cartels were discontinued voluntarily followed by leniency applications, while five were detected by the cartel authority (see Table 5).

6.2 Individual cases

While it is difficult to determine what caused a cartel member to quit and report an agreement, the verdicts provide some insights into the conflicts preceding the termination of cartels in our sample. We find that the introduction of new members can be disruptive if they do not agree with the terms or balance of power within the cartel. Furthermore, the documentation shows that changing market conditions can create incentives to exit or cheat on the agreed terms. Lastly, the data provides insights into how cartel participants perceived their exchanges and how they thought about the risks and costs associated with their misconduct.

6.2.1 Personal conflicts

The Wallpaper cartel, for example, was characterized by a constant power struggle between the two industry leaders X and Q, which other cartel members described as a “rooster fight”. This conflict was intensified when the two managing directors of Q transferred their responsibilities to their sons who then wanted to “position themselves” within the industry and improve the rank of their firm within the producers’ hierarchy. As they were aware of the cartel agreement from their fathers, they initiated a meeting between the competitors which led to a consensus on another price increase. In order to prove their re-empowerment, the two new managers wanted to be the first to announce the price increase, which offended the older and more experienced managing director of the other industry leader X:

He [the older manager] insisted that his firm would announce the increase first, which was also motivated by prestige-reasons. After no consensual solution was found, he stated that his firm would increase the prices as agreed upon and regarding the order of the announcements, all firms should do as they pleased (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

The conversation was then finished and the firms implemented the prices without a particular order. In the subsequent period, the market position of X grew in strength and X began to change prices single-handedly while terminating the communication with his competitors. This behavior created distrust and insecurity within the industry and after the managers of Q had gained knowledge of the magnitude of fines for anti-competitive agreements, they decided to file a leniency application. This decision caused a conflict with the previous management, who had advised against this:

He [the father/uncle and previous manager] could not have imagined that X would report the cartel and thus suggested to simply reduce all contact with competitors to a legal level. The marker was placed without his knowledge and he explicitly stated his regret to have hurt his former negotiating partners. To this day he finds the decision to report outrageous (OLG, 2 Kart 1/17).

While the cartel had already stopped operating, it then fully broke down and there was no (documented) coordination on prices anymore.

6.2.2 Market changes

Changing market conditions were identified as one of the reasons for the collapse in the Cement cartel. When the cartel was formed in the early 1990s, the six largest firms in the industry had agreed on sales quotas in the regional sub-cartels which were mainly based on historical market shares. One of the main members, R, who was part of the agreements in West and East Germany, expanded his production capacities though and wanted to increase the market share. As this would have violated the cartel’s terms, he systematically under-reported his sales to the industry association, were the production was monitored (Harrington et al., 2015). When this deviation came to light, the other cartelists did not break up the cartel, but instead tried to keep it up “by all means” and even supported R in the return to the cartel yet still demanded compensation for the sales lost (OLG, VI-2a Kart 2-6/08):

After the “fraudulent quantities” were discovered, R had to return to the original sales quotas and needed to undertake compensatory measures which had significantly negative consequences for the firm. He [the representative] “clenched the fist in his pocket” but wanted to avoid a competitive confrontation and chose “peace over war” at that time (OLG, VI-2a Kart 2-6/08).

The cartel kept on operating until 2001, when R conducted an internal strategy revision which included an investigation on anti-competitive conduct and decided to leave all cartels. The new chief executive informed the other cartel members on this decision and announced that the firm would leave the industry association. All regional cartels collapsed and communication between participants was terminated. In the investigation that followed shortly after, R filed for leniency and cooperated with the FCO.Footnote 19

6.2.3 Individual perception

Lastly, the documentation offers some insight into the emotional reaction of cartel members to their wrongdoing. In the Sweets cartel, for example, several witnesses later admitted that the conversations about their company strategies had irritated them:

One witness stated that he perceived the open communication between sales managers as unusual, especially since the conditions that were granted to the retailers were not even discussed within the company in such an outspoken manner. Another witness [...] stated that everybody should have known that such conversations were not okay. This topic [of price increases] should have alienated all participants (OLG, V-4 Kart 6/15).

As the two cartel members who represented the industry association were lawyers though, the participants were reassured. Still, nobody ever expressed concern or tried to clarify the situation (OLG, V-4 Kart 6/15).

The participants of the Beer cartel were already used to sharing confidential information and nobody was irritated by the attempt to coordinate prices. On one meeting though, the business unit manager of firm B was temporarily replaced and while the new member saw this exchange as an opportunity at first, he later regretted his actions:

The temporary business unit manager saw the meeting as a chance that would only be offered once in his life to meet the leaders of the large German producers and talk to them at eye level. [...] He let himself get carried away and was one of the first participants who shared confidential information about the pricing strategy of his firm with the competitors. Shortly after the meeting, he realized the unlawfulness of the conversation and had a strongly negative emotional reaction (OLG, V-4 Kart 2/16).

Four years later, firm B filed for leniency and initiated the prosecution of the cartel by the FCO (FCO, B10-105/11). It is not documented though why B reported the cartel. It may be noteworthy though that firm B underwent several ownership changes in the years before the firm filed for leniency. The new owner also filed for leniency in other regional cartels outside Germany in other jurisdictions. Hence, the leniency application in Germany may have been part of a broader compliance strategy of the new multinational owner.

7 Discussion and conclusion

While the extensive empirical and theoretical research on cartels has provided valuable insights into the determinants of cartel formation and stability, the inner workings of cartels have received only little attention so far—even though collusive agreements are reached between individuals, who need to trust each other and develop structures that enable them to coordinate behavior absent legally binding contracts. Therefore, we have conducted a qualitative study of 15 German cartels that operated over the last 30 years based on the documentation of the German Federal Cartel Office and court verdicts. The aim of this paper was to investigate how cartel members have managed to establish trust and ensure cooperation over years or even decades in spite of the external and internal risks. Our analysis provides details on the personal characteristics of participants, their networks and the internal structures of the cartels, as well as the communication necessary to reach and maintain agreements. We also investigate the role of industry associations and potential reasons for cartel breakup.

Our main finding concerns the homogeneity of cartel members and sheds further light not only on the stability of cartels but also their formation—an area which is still not well understood but might become more comprehensible when the personal traits of executives are taken into account. The vast majority of the 158 documented participants are men between the age of 45 and 60. This finding may partially reflect the fact that such individuals dominate higher management positions where they have the necessary information and power that allow them to coordinate firm behavior in the first place. Note, however, that even though females are still underrepresented in these positions, their general share is much higher than the two of 158 active participants in the 15 cartels studied. As indicated by the related literature on factors that create trust, homogeneity positively affects expectations about each others’ behavior and facilitates the establishment of trust necessary to initiate and maintain collusion which potentially makes it a central prerequisite for cartel formation.

We further find that cartels often develop from existing networks within the industry and rely on these structures to coordinate the agreements. Often these networks were embedded in trade associations. Being a member of an association provides firm representatives with the opportunity to regularly meet with competitors and to develop professional and personal bonds. Expanding the topics discussed to anti-competitive contents is only a small step and does not require elaborate—and potentially suspicious—organization. As our data shows, trade associations may not only provide the opportunity to create networks, but sometimes also actively support cartel members in the implementation and monitoring of agreements.

Communication is central in cartels and was documented in varying frequencies and methods in our sample. We find that major decisions, especially fixing or updating the general terms of a cartel, were discussed in person, while the implementation and adjustments would often be coordinated via exchanges on the phone or sometimes in e-mails. This emphasizes the role of trust necessary to form a cartel, which is best achieved in personal exchanges. It also highlights how the need to conceal actions from outsiders whilst ensuring their efficiency affects communication. These two motives apply to the internal organization as well, as most cartels divide responsibilities and tasks between members of different hierarchical or regional groups. The internal structures of cartels in this sample is very heterogeneous though and depends on the nature of the product and market, the duration of the agreement and the previously established structures within the industry.

Lastly, we gained some insights into why conflicts emerge and members would exit a cartel and in some cases report it to competition agencies. As cartels are formed between individuals who trust each other, a disruption in group composition can destabilize an agreement, especially if new members do not agree with the current terms or anti-competitive behavior in general. Finally, individuals—especially in smaller firms without proper compliance programs—may not always realize that their behavior is unlawful and only report a cartel once they become aware that their behavior constitutes a violation of antitrust laws.

While we do not provide quantitative results on the determinants of cartel stability, our analysis does offer detailed insights into the inner workings of German cartels and allows us to draw up recommendations for competition policy. To prevent cartel formation in the first place, the promotion and support of management diversity may help to hinder the formation of homogeneous networks, such as “old boys clubs” that create the personal bonds and trust necessary to engage in illegal conduct. This diversity does not only concern gender, but also characteristics like nationality, language, cultural background, age, and education. Furthermore, competition agencies and also companies might want to increase awareness regarding the unlawfulness of anti-competitive behavior and the associated costs in the establishment and evaluation of compliance programs. Agencies could also take diversity into consideration in the enforcement of competition law and investigate industries that exhibit homogeneous and long-established networks between managers, as they might be especially prone to cartel formation. On that note, the role of trade associations and their committees could be evaluated. While trade associations provide great support for their members and improve the exchange between industry and politics, they are also at risk of facilitating cartel formation. Increased advocacy work and clear guidelines on the legality of exchanges within associations could decrease that risk.

It needs to be noted that our study has several limitations and potential biases. The sample is drawn from the population of detected cartels, which might have had less efficient structures than those who still operate. Furthermore, the prosecution of a cartel depends on the competition agency, which might focus on cases that are most relevant for the larger public, require fewer resources or yield high prospects of success. Additionally, our data is limited, as we do not have full information on all cases. The FCO does not necessarily collect data on all cartel participants and the court verdicts only exist for cases that were appealed. This “dependency on prosecution as a sample selection criterion” (Levenstein & Suslow, 2006a) is a common issue in the research on cartels and misconduct in general and one needs to be cautions in generalizing the results to a larger cartel population (see also Harrington, 2006; Bertrand & Lumineau, 2016).

In order to improve further research on the topic and possibly provide generalizable results, we recommend an increase in the collection of data on the participants and inner structures of cartels prosecuted by competition agencies. If this data was anonymized and made available, future research could provide additional evidence for example on the role of women in cartels and how their presence in the management of firms affects cartel formation. It would also be of interest how collusive agreements are reached and sustained as markets become more globalized and industry networks less concentrated. In this regard, further research could compare recent cartels from different countries or institutional backgrounds and identify how the cultural and geographical environment affect the formation and longevity of collusive agreements. An improvement in the availability of data might also allow to gain more insights on how cartel members react to disruptions and what distinguishes cartels that manage to operate for long periods of time from those who collapse early on. In sum, there are still gaps in the understanding of cartel formation, their functioning and their longevity. Further research could promote the development of more nuanced models and improve competition policy, both in the prevention of cartels as well as in their prosecution.

Notes

Germany is a country of special interest for cartel analysis. While it was once the “land of cartels” it was also the first country in Europe to establish strict anti-cartel laws and now rigorously prosecutes anticompetitive behavior (Haucap et al., 2010) However, there is still little work on cartels in Germany, which we aim to address in this study.

In Germany not only the firms involved in a cartel are fined, but typically the associated individuals are also fined separately.

Note that the extent of the published reports differs between cases. Therefore, the qualitative analysis does not contain information on all variables for each cartel.