Abstract

Electricity and water tariffs are undergoing significant changes due to smart metering, retail competition, and regulatory changes. Consumers now have to choose between different tariffs which are getting more and more complex. Theoretically, these new tariffs aim to use more cost-reflective pricing to incentivise consumers to adopt the right behaviours. However, empirical evidence from real pricing shows that consumers are confused by the complexity. Based on a lab experiment, this paper investigates how electricity and water consumers adopt more or less complicated tariffs and adapt their behaviours accordingly. We show that subjects prefer simple tariffs over complex ones. However, when they receive adequate information about tariffs and appropriate behaviours, they choose more complex tariffs. These results argue in favour of self-selection of tariff forms, in order to account for consumers’ different abilities to respond to the price signal. Lastly, we discuss the appropriateness of using a price mechanism to incentivise consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Active demand response refers to the new options given to electricity consumers by smart meters to make the electricity system flexible and thus flatten peak demand. Consumers can shift consumption away from peak-demand times when electricity is costly and polluting to produce, by running their washing machines or tumble-dryers or charging their electric vehicles in off-peak periods (when the electricity rate is cheaper). This saves energy and increases system efficiency through reduced grid infrastructure investment and better system management.

Non-monetary incentives complement monetary incentives. They refer to personal feedback (information, advice) and social feedback (comparisons with other households consumption). They are based on behavioural economics and psychological theories (Thaler and Mullainathan 2000).

New electricity dynamic tariffs (such as real-time pricing, critical peak pricing, and peak-time rebates) are more cost-reflective than the three tariffs considered since they are time-based tariffs. They are used to stimulate active demand response in the electricity sector.

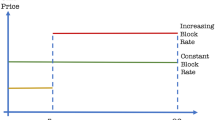

A standard result in utility regulation originally developed by Coase (1946) is that efficiency requires two-part tariffs with marginal prices set to marginal costs and fixed fees equal to each customer’s share of fixed costs

Loi n. 2013-312 du 15 Avril 2013 visantà préparer la transition vers un système énergtique sobre et portant diverses dispositions sur la tarification de l’eau et sur leséoliennes

Rational choice models assume that consumers engage in economically rational information-processing and decision-making from the perspective of maximising personal gain.

According to Coase (1946), the two-part tariff has two components, a volumetric charge, and a fixed monthly fee. In the optimal two-part tariff, the volumetric charge is set equal to marginal cost, and the fixed monthly fee has to be set equal to each customer’s share of fixed costs.

It is also worth noting that the majority of electricity consumers are traditionally relatively price-inelastic.

In this paper, we focus on the behavioural biases linked to limited rationality, ignoring the other two types of biases-bounded willpower and bounded-self-interest-identified by Thaler and Mullainathan (2000).

See Hobman et al. (2016) for a detailed review of the behavioural biases involved in the uptake and usage of cost-reflective electricity pricing and the practical solutions that can be proposed to reduce the distortions induced by each type of bias.

According to the utility theory of Von Neuman and Morgenstern (1944), the optimal decision for a rational individual is the one that maximises the utility function, weighted by the probabilities of the occurrence of different alternatives. Nevertheless, as shown in many studies since the seminal paper of Kahneman and Tversky (1979), actual behaviour does not follow expected utility maximisation, and individuals estimate the welfare consequences of their choices according to different behavioural elements. Thus, individuals may make such estimations based on changes implied by their decisions compared to a given individual reference point, which might be impacted by various features: past experiences, social norms, or how the alternative is presented (framing effect).

Faruqui et al. (2010) show that time-variable pricing creates transaction costs for customers, who must track price changes and respond accordingly.

Hartman et al. (1991) find exciting results regarding the status quo effect in electricity consumption. They use contingent valuation survey data to empirically investigate the existence of a status quo effect in consumer valuations of a particular unpriced product, the reliability of residential electricity service (i.e. Power outage). They find a strong status quo effect which corroborates the contingent valuation literature on consumer “irrationality”.

The picture is somewhat more complex, since until now there has been a regulated tariff that remains the default tariff offered by the incumbent and serves as a reference point (inducing a potential framing effect). For a discussion of the implications of this coexistence of regulated and non-regulated tariffs, see Martimort et al. (2020).

Our experimental design is similar to the one used in Robin et al. (2018). However, our paper focuses on conservation behaviour whereas they also address active demand response. Consequently, we consider only three time-independent tariffs (leading to six decisions) while they also consider dynamic pricing (testing for up to thirty decisions based on the different specifications of each tariff (in terms of the level of the fixed part and expected value)). The originality of our experiment lies in the fact that we consider two goods (electricity and water) and aim at investigating a potential “good effect”.

Detailed procedure and instructions are available upon request.

We recruited participants in the experiment representing a variety of consumers, selecting them according to various household characteristics (age, gender, household composition, address (Paris or suburb), type of housing (individual house or multiple dwelling) and other socio-economic variables). They had to declare that they were actually paying their electricity and water bills to avoid including participants who had no clue as to what choosing a tariff for electricity or water means.

The survey is based on the interactive tool provided by electricity and water suppliers as well as the guides published by French Agency for the environment and energy saving, Ademe (Agence de l’environnement et de la maitrise de l’ énergie).

Consumption expressed through a confidence interval and not as an average. This point is significant because, on the one hand, it allows the introduction of risk into the choice, and on the other hand, it ensures that the experiment is not reduced to a mental arithmetic contest.

Articles L. 224-3 et L. 224-7 du code de la consommation.

In France (2017, from INSEE Data): 36,2% (1 person), 32;6% (2 persons), 13,7% (3 persons), 11,5% (4 persons), 5,9% (>4 persons)

Integrating the income variable directly into the model did not appear relevant because the income gap can be huge between people living in the Paris region, with a similar profession.

See Hobman et al. (2016) for a review on behavioural economics-inspired solutions.

References

Ascarza, E., Lambrecht, A., & Vilcassim, N. (2012). When talk is free: The effect of tariff structure on usage under two-and three-part tariffs. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(6), 882–899.

Buckley, P. (2020). Prices, information and nudges for residential electricity conservation: A meta-analysis. Ecological Economics, 172(1), 106635.

Carlin, B. I. (2009). Strategic price complexity in retail financial markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 91(3), 278–287.

Coase, R. H. (1946). The marginal cost controversy. Economica, 13(51), 169–182.

Crampes, C., & Lozachmeur, J. M. (2014). Tarif progressif, efficience et équité. Revue d’économie industrielle, 148, 133–160.

Dütschke, E., & Paetz, A. G. (2013). Dynamic electricity pricing-which programs do consumers prefer? Energy Policy, 59, 226–234.

Eckel, C. C., Grossman, P. J., Johnson, C. A., de Oliveira, A. C., Rojas, C., & Wilson, R. K. (2012). School environment and risk preferences: Experimental evidence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 45(3), 265–292.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2017). Tackling environmental problems with the help of behavioural insights.

Faruqui, A., Hajos, A., Hledik, R., & Newell, S. (2010). Fostering economic demand response in the midwest iso. Energy, 35(4), 1544–1552.

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42.

Gaubert, J. (2020). National energy ombudsman-2018 activity report. Report.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments.

Harding, M., & Sexton, S. (2017). Household response to time-varying electricity prices. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 9, 337–359.

Hartman, R. S., Doane, M. J., & Woo, C. K. (1991). Consumer rationality and the status quo. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(1), 141–162.

Hobman, E. V., Frederiks, E. R., Stenner, K., & Meikle, S. (2016). Uptake and usage of cost-reflective electricity pricing: Insights from psychology and behavioural economics. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 57, 455–467.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Ito, K. (2014). Do consumers respond to marginal or average price? Evidence from nonlinear electricity pricing. American Economic Review, 104(2), 537–63.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Loewenstein, G., & Thaler, R. H. (1989). Anomalies: Intertemporal choice. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3(4), 181–193.

Malin, E., Martimort, D. (2001). Les limites à la discrimination par les prix. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique, pp. 209–249.

Martimort, D., Pouyet, J., & Staropoli, C. (2020). Use and abuse of regulated prices in electricity markets:“how to regulate regulated prices?’’. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 29(3), 605–634.

Mayol, A. (2017). Social and nonlinear tariffs on drinking water: Cui bono? empirical evidence from a natural experiment in France. Revue d’économie politique, 127(6), 1161–1185.

Mayol, A., & Porcher, S. (2019). Tarifs discriminants et monopoles de l’eau potable: une analyse de la réaction des consommateurs face aux distorsions du signal-prix. Revue économique, 7, 213–247.

Miravete, E. J. (2003). Choosing the wrong calling plan? ignorance and learning. American Economic Review, 93(1), 297–310.

Robin, S., Lesgards, V., Mihut, A., & Staropoli, C. (2018). Linear vs. non-linear pricing: What can we learn from the lab about individual preferences for electricity tariffs? Mimeo. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:hal:journl:hal-01822956

Shin, J. S. (1985). Perception of price when price information is costly: Evidence from residential electricity demand. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 67, 591–598.

Simon, H. A. (1976). From substantive to procedural rationality. In 25 years of economic theory, pp. 65–86. Springer.

Thaler, R. (1981). Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Economics Letters, 8(3), 201–207.

Thaler, R. H., & Mullainathan, S. (2000). Behavioral Economics. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge. New Haven, CT, London: Yale University Press.

Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization. London: MIT Press.

Von Neuman, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior. New York: Wiley.

Acknowledgements

The experiments were conducted in the Laboratoire d’Economie Experimentale de Paris (LEEP), Université Paris 1 - Paris School of Economics. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Chaire EPPP (IAE Paris), BETA (Université de Lorraine) and the ARIANE Projet from the Grand Est region. We thank Maxim Frolov for his excellent assistance with programming the software and help with running the sessions. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Extended table: marginal effects from probit model without incentives

See Table 6.

1.2 Extended table: marginal effects from the probit model with incentives

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayol, A., Staropoli, C. Giving consumers too many choices: a false good idea? A lab experiment on water and electricity tariffs. Eur J Law Econ 51, 383–410 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09694-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09694-6