Abstract

Theoretical work in behavioral economics aims to modify assumptions of standard neoclassical models of individual decision-making to better comport with observed behavior. The alternative assumptions fall into at least two categories: non-standard preferences and psychological mistakes. Applications of behavioral economics models in law, however, tend to assume that deviations from standard neoclassical models are meant to build in psychological mistakes that produce regrettable choices. Often follow-on policy prescriptions suggest interventions that either help individuals choose correctly or go further to substitute the “correct” choices for those that mistake-prone individuals might choose in error. Such policy prescriptions are ill suited in cases where the applied behavioral economics model assumes non-standard preferences as opposed to psychological mistakes. This essay provides examples of models in each category and examples of mistaken applications of models that assume non-standard preferences rather than psychological mistakes. It also suggests ways to avoid errors when applying behavioral economics theories in law.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I use the terms “neoclassical economics models,” “rational choice theory,” and “standard economics models” interchangeably.

The rise of behavioral economics in law is an example of what Guido Calabresi (2016: 2–5) refers to as “Law and Economics,” the altering of economic theory to fit the reality of legal environments. He contrasts this with “Economic Analysis of Law,” which labels reality as irrational if it does not comport with predictions from theories built up from first principles. For another view on the distinction between “law and economics” and “economic analysis of law,” see Harnay and Marciano (2009).

I use the term “psychological mistakes” to distinguish mistakes caused by psychological influences from those caused by, for example, a lack of perfect information and inability to perfectly predict uncertain future events. Standard economic theory sometimes predicts such non-psychological mistakes or inefficiencies.

Standard models alternatively assume that individuals assign either objective or subjective probabilities to uncertain outcomes (Schoemaker 1982).

For example, if one prefers $110 in 1 month to $100 today, then $110 in 1 year and 1 month is preferred to $100 in 1 year.

The starting point is often referred to as a reference point (Kahneman and Tversky 1979).

Wright and Stone (2012b: 860–861) explain, “Behavioral economics examines ways in which economic actors deviate from predicted conduct under rational choice assumptions—in other words, how and why actors behave irrationally. Behavioral law and economics attempts to apply these insights through policy measures designed to systematically ‘debias’ firms and individuals.” Levinson (2012: n.1) similarly states, “Behavioral law and economics is the study of how cognitive biases or limitations predictably affect decision-makers' behavior in ways that cause the behavior to deviate from what is economically beneficial.”

Thanks to Eyal Zamir for reminding me that scholars might also make the opposite mistake—mistaking theories grounded in psychological mistakes for theories grounded in non-standard preferences. These errors are equally as concerning as those I focus on here. In the same vein, economics and psychologists, in addition to legal scholars, sometimes make mistakes when characterizing assumptions.

It is important to note here that I did not canvas the entire literature to collect sufficient evidence to make claims about the prevalence of mistakes about mistakes. Examples were relatively easy to find, however. In addition, overly narrow definitions and characterizations of the field are quite common (e.g., “Behavioral economics is one of the most significant developments in economics over the past thirty-six years. The field combines economics and psychology to produce a body of evidence that individual choice behavior departs from that predicted by neoclassical economics in a number of decisionmaking situations. These departures from rational choice behavior are said to be the result of the individual’s “cognitive biases,” that is, systematic failures to act in one’s own interest because of defects in one’s decisionmaking process. The documentation of these cognitive biases in laboratory experiments has been behavioral economics’ primary contribution to microeconomics. These biases, behavioral economists assert, demonstrate systematically irrational choice behavior by individuals and firms. This irrational behavior, in turn, breaks the link between revealed preference and individual welfare upon which neoclassical economic theory depends.” (Wright and Ginsberg 2012, p. 1034); “…B[ehavioral] L[aw and] E[conomics] relies, at its core, on the concept that people make predictable errors in judgment.” (Rachlinski 2011, p. 1682).

Opportunity cost is the lost opportunity from forgoing the next best alternative. Marginal cost is the cost incurred when one decides to engage in the next increment of the chosen activity (e.g., the cost of increasing the size of one’s army by one additional soldier). Sunk costs are past expenditures that cannot be undone.

Standard models are framed in terms of decision utility, as described in the text. Behavioral models sometimes employ the notion of experienced utility, which refers to one’s hedonic experience associated with an outcome. Inability to predict how different outcomes might impact our experienced happiness is the basis for some behavioral economics models (see, e.g. Kahneman and Thaler 2006). Behavioral economics has introduced a variety of utilities (e.g., anticipatory utility, diagnostic utility, remembered utility, real-time utility, and residual utility) (see Wilkinson and Klaes 2018: 93–100). These distinctions, while generally important, are outside this essay’s scope.

Less extreme versions are flexible about the nature of the preferences driving choices. For one view of the assumptions’ history and development, see Harrison (1985).

If A and B are the only choices, an individual might prefer A to B, or prefer B to A, or be indifferent between them.

Others exist. The discussion here is meant only to provide examples. Furthermore, it’s important to reiterate that the theoretical and empirical literatures related to each of the examples provided in this Part are vast. Each contains multiple theories, some assuming non-standard preferences and some assuming psychological mistakes. Some theories have found more support in the data than others, but each literature contains multiple theories that are able to explain substantial portions of existing data. Those who import behavioral economics theories into legal scholarship sometimes mistake theories of non-standard preferences for theories of mistakes, and they also fail to acknowledge theories other than the one (or few) they apply and draw normative claims from. Both oversights lead to confusion in legal scholarship.

Willingness to pay is measured by the most amount of money one is willing to exchange to obtain some item. Willingness to accept is measured by the least amount of money one is willing to accept in exchange for giving up an endowed item.

This general phenomenon is commonly known as the “endowment effect.” This term causes confusion, however, because it connotes a particular explanation, that the endowment somehow causes the observed effect. While some theories focus on the endowed nature of the good, several competing theories that focus on other features of the contexts are able to explain large swaths of observed choices. Thus, neutral labels such as “valuation gap” and “exchange asymmetry” are less likely to confuse the reader or compel placing excessive weight on one theory over others.

For a comprehensive review of the literature, see Zeiler (2018). In addition to summarizing the numerous theories that might explain observed reluctance to trade, the review critiques techniques used by empiricist to elicit choices. Such controversies exist in most if not all economics literatures. Unfortunately, scholars who import theories from economics and psychology into legal analyses often gloss over such inherent messiness.

The authors employ an additional set of technical assumptions that are irrelevant for our purposes.

Much evidence suggests that one’s endowment does not impact valuation and thus does not support endowment theory. A substantial portion of existing data, however, supports alternative theories (e.g., Kőszegi and Rabin 2006) that assume that reference points are set by expectations and not endowments (see Zeiler 2018).

None of the works Fried cites to support the claim of irrationality actually claim that reluctance to trade is irrational. In fact, two cited articles (Korobkin 2003: 1280; Korobkin 1998: 666–667) claim that the endowment effect is not per se irrational. Fried (2013: 1260) also refers to loss aversion and reference dependence as “cognitive biases.”

“There have been some interesting semantic discussions of whether or not, even if it exists, the endowment effect is formally irrational. One can argue, for example, that once a person's preference for the item has increased, then acting consistent with that preference is rational. Similarly, one could argue (perhaps tautologically) that seemingly irrational behavior simply reflects rational, utility-maximizing behavior among people who share an unexpectedly odd utility function. Alternatively, one could simply say that observed disparities challenge expected utility theory as a good model for decision making under uncertainty.”

Alternatively, preferences that compel acts that infringe on others’ rights (e.g., A prefers to steal B’s possessions) should be regulated in ways that protect recognized rights. The main point here is that regulatory tactics will differ depending on how we interpret the problems that give rise to the need for intervention.

In support of this normative claim, Fried cites to Arien and Tontrup (2015). Arlen and Tontrup, in their normative discussion, however, assume that reluctance to trade is caused by a preference to avoid feelings of regret and not by loss aversion. Although Arlen and Tontrup (2015: 175–178) do not have loss aversion in mind, they seem to mistakenly characterize regret avoidance as a mistake, describing regret avoidance as a bias in need of a remedy. They (2015: 153) describe actions in the absence of regret aversion as “rational.” They do this despite the fact that the authors of regret theory (Loomes and Sugden 1982: 822), which Arlen and Tontrup cite early on, explicitly characterize the model of regret avoidance as a model of rational choice.

Korobkin (2003: 1265) explains “If the government wishes to promote the efficient use of resources by redistributing rights if and only if the valuation of those rights by the winners exceeds the valuation of the losers, but WTA is considered an illegitimate measure of value, then permitting the community to condemn landowners' rights and requiring it to pay a fixed price determined by the state might be an appropriate policy.” Korobkin (2003: 1280), however, does recognize the possibility that reluctance to trade might not be irrational, stating that “the endowment effect is not obviously ‘irrational’ behavior: a preference for what one has over what one does not have…is no more troublesome than a preference for chocolate ice cream over vanilla.”.

See Mas-Colell et al. (1995: 733–736) for a general description of the standard discounting model.

As with most observations studied in economics, disagreement exists over interpretation and causal mechanisms. Stahl (2013) lists studies that have posed challenges to the validity of experiments reporting evidence of present bias and offering a rational choice theory explanation for observed inconsistent time preference.

This excellent review catalogs difficulties with measuring individual time preferences.

Loewenstein and Prelec (1992) provide one of the earliest lists of anomalies.

The model assumes two selves: a myopic doer, who derives utility only from current consumption, and a planner, who is concerned with lifetime utility. The planner rationally chooses to impose constraints on the doer when the costs of doing so are relatively low.

For example, Loewenstein and Prelec (1992: 595) state, “Our model by no means incorporates all important psychological factors that influence intertemporal choice. For example, like any model with nonconstant discounting, it yields time-inconsistent behavior or ‘myopia’…. However, it cannot explain the high levels of conflict that such myopic behavior often evokes. Intertemporal choice often seems to involve an internal struggle for self-command….At the very moment of succumbing to the impulse to consume, individuals often recognize at a cognitive level that they are making a decision that is contrary to their long-term self-interest. Mathematical models of choice do not shed much light on such patterns of cognition and behavior.” They (1992: 592) do, however, recognize potential conditions for suboptimal choice: “Relative to normative theory, our model suggests that people may tend to prefer plans that sacrifice the medium-range future for the sake of the short and the long term. There is nothing clearly wrong with this, provided that one can commit to an entire plan at the moment of decision. However, if the optimal plan can be recalculated at later points in time, then the planned sacrifice in midrange consumption will not take effect…. As a result, a bias in favor of the long and short runs may in practice yield behavior that is oriented only to the short run.” Furthermore, Loewenstein and Prelec (1992: 581) observe, “The shape and reference point assumption reflects basic psychophysical considerations: extra attention to negative aspects of the environment, decreasing sensitivity to increments in stimuli of increasing magnitude, and cognitive limitations” (emphasis added).

For example, if I cannot use a commitment device to start saving for the future, I might plan to start saving in a year, but when the time comes I chose to consume and not save and make another plan to start saving in the future. And, so on. I never save, which puts my future self in a bind.

While Rizzo and Whitman (2009: 913-914) state, “People who engage in hyperbolic discounting may exhibit time inconsistency: they will make decisions about future trade-offs and then reverse those decisions later…. Behavioral economists take this sort of inconsistency as evidence of irrationality,” the authors do not cite to any authority for this claim. They point the reader, however, to Frederick et al. (2002) to support their definition of hyperbolic discounting. Recall that these authors express doubts over whether inconsistent time preferences should be considered mistakes.

They state, “This curve gives preference a property that most people would call irrational—an innate tendency to switch from better-later goods to poorer-earlier goods simply as the earlier goods become imminently available.” (p. 831).

Specifically, Viscusi (2007: 239–240, fn. 85) states, “Given that people's revealed intertemporal preferences display hyperbolic discounting, should policy prescriptions for discounting practices reflect these preferences? My view is that this form of intertemporal irrationality should not be incorporated into official discounting practices, which instead should be based on the opportunity cost of capital rather than the irrational, myopic concerns embodied in hyperbolic discounting.”

For more on this, see Zeiler (2010).

Klass and Zeiler (2013) focus on endowment theory, but the same argument can be generalized to behavioral economics theory.

References

Ainslie, G., & Monterosso, J. (2003). Will as intertemporal bargaining: Implications for rationality. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 151(3), 825–862.

Angner, E. (2012). A Course in Behavioral Economics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian.

Arien, J., & Tontrup, S. (2015). Does the endowment effect justify legal intervention? The debiasing effect of institutions. Journal of Legal Studies, 44(1), 143–182.

Arkin, R. M., Appelman, A. J., & Burger, J. M. (1980). Social anxiety, self-presentation, and the self-serving bias in causal attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(1), 23–35.

Bayes, T., & Price, R. (1763). An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances. Philosophical Transactions, 53, 370–418.

Bowers, J. (2008). Contraindicated drug courts. UCLA Law Review, 55(4), 783–836.

Buccafusco, C., & Sprigman, C. (2010). Valuing intellectual property: An experiment. Cornell Law Review, 96(1), 1–46.

Calabresi, G. (2016). The future of law and economics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cartwright, E. (2014). Behavioral economics. London: Routledge.

Chung, S., & Herrnstein, R. J. (1967). Choice and delay of reinforcement. Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 10(1), 67–74.

Cohen, J. D., Ericson, K. M., Laibson, D., & White, J. M. (2016). Measuring time preferences. NBER working paper no. 22455. National Bureau of Economic Research, https://doi.org/10.3386/w22455.

Croson, R., & Sundali, J. (2005). The gambler’s fallacy and the hot hand: Empirical data from casinos. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 30(3), 195–209.

Elster, J. (1996). Rationality and the emotions. Economic Journal, 106(438), 1386–1397.

Farber, D. A. (2003). From here to eternity: Environmental law and future generations. University of Illinois Law Review, 2003(2), 289–336.

Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Soane, E., Nicholson, N., & Willman, P. (2010). Thinking, feeling and deciding: The influence of emotions on the decision making and performance of traders. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(8), 1044–1061.

Fischhoff, B. (1975). Hindsight ≠ foresight: The effect of outcome knowledge on judgment under uncertainty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 1(3), 288–299.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 351–401.

Fried, B. H. (2013). But seriously, folks, what do people want? Stanford Law Review, 65(6), 1249–1268.

Fudenberg, D., & Levine, D. K. (2006). A dual-self model of impulse control. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1449–1476.

Gandhi, S. J. (2008). Understanding students from a behavioral economics perspective: How accelerating student loan subsidies generates more bang for the buck. Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy, 17(2), 130–167.

Hanson, J., & Yosifon, D. (2004). The situational character: A critical realist perspective on the human animal. Georgetown Law Review, 93(1), 1–180.

Harnay, S., & Marciano, A. (2009). Posner, economics and the law: From “law and economics” to an economic analysis of law. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 31(2), 215–232.

Harrison, J. L. (1985). Egoism, altruism, and market illusions: The limits of law and economics. UCLA Law Review, 33(5), 1309–1363.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., & Puto, C. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: Violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(1), 90–98.

Jolls, C., Sunstein, C. R., & Thaler, R. (1998). A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanford Law Review, 50(5), 1471–1550.

Jones, O. D., & Brosnan, S. F. (2008). Law, biology, and property: A new theory of the endowment. William and Mary Law Review, 49(6), 1935–1990.

Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D., & Thaler, R. H. (2006). Utility maximization and experienced utility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 221–234.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Klass, G., & Zeiler, K. (2013). Against endowment theory: Experimental economics and legal scholarship. UCLA Law Review, 61, 2–64.

Korobkin, R. (1998). The status quo bias and contract default rules. Cornell Law Review, 83(3), 608–687.

Korobkin, R. (2003). The endowment effect and legal analysis. Northwestern University Law Review, 97(3), 1227–1294.

Kőszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2006). A model of reference-dependent preferences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(4), 1133–1165.

Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 443–477.

Levinson, J. D. (2012). Superbias: The collision of behavioral economics and implicit social cognition. Akron Law Review, 45(3), 591–646.

Loewenstein, G. (2000). Emotions in economic theory and economic behavior. American Economic Review, 90(2), 426–432.

Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (1992). Anomalies in intertemporal choice: Evidence and an interpretation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 573–597.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1982). Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. Economic Journal, 92(368), 805–824.

Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M. D., & Green, J. R. (1995). Microeconomic theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, R. F. (1976). Preferences over time. In R. Keeney & H. Raiffa (Eds.), Decisions with multiple objectives: Preferences and value tradeoffs (pp. 473–514). New York: Wiley.

Mitchell, G. (2005). Libertarian paternalism is an oxymoron. Northwestern University Law Review, 99(3), 1245–1277.

O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2001). Choice and procrastination. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 121–160.

Pidgeon, N., Hood, C., Jones, D., Turner, B., & Gibson, R. (1992). Risk perception. In Risk: Analysis, perception and management (pp. 89–134). The Royal Society.

Pratt, J. W. (1964). Risk aversion in the small and in the large. Econometrica, 32(1–2), 122–136.

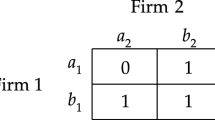

Preston, L. E. (1961). Utility interactions in a two-person world. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 5(4), 354–365.

Rachlinski, J. (2011). The psychological foundations of behavioral law and economics. University of Illinois Law Review, 2011, 1675–1696.

Rizzo, M. J., & Whitman, D. G. (2009). The knowledge problem of new paternalism. Brigham Young University Law Review, 2009(4), 905–968.

Samuelson, P. A. (1937). A note on measurement of utility. Review of Economic Studies, 4(2), 155–161.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1078.

Schoemaker, P. (1982). The expected utility model: Its variants, purposes, evidence and limitations. Journal of Economic Literature, 20(2), 529–563.

Shafir, E., & Le Boeuf, R. A. (2002). Rationality. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 491–517.

Stahl, D. O. (2013). Intertemporal choice with liquidity constraints: Theory and experiment. Economic Letters, 118(1), 101–103.

Stiglitz, J. (1993). Economics. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Strotz, R. H. (1955). Myopia and inconsistency in dynamic utility maximization. Review of Economic Studies, 23(3), 165–180.

Thaler, R. H., & Shefrin, H. M. (1981). An economic theory of self-control. Journal of Political Economy, 89(2), 392–406.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4147), 1124–1131.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1039–1061.

Viscusi, W. K. (2007). Rational discounting for regulatory analysis. University of Chicago Law Review, 74(1), 209–246.

von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1944). Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Walster, E. (1967). ‘Second guessing’ important events. Human Relations, 20(3), 239–249.

Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 806–820.

Wilkinson, N., & Klaes, M. (2018). An introduction to behavioral economics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian.

Wright, J. D., & Ginsberg, D. H. (2012). Behavioral law and economics: Its origins, fatal flaws, and implications for liberty. Northwestern University Law Review, 106(3), 1033–1088.

Wright, J. D., & Stone, J. E. (2012a). Misbehavioral economics: The case against behavioral antitrust. Cardozo Law Review, 33(4), 1517–1554.

Wright, J. D., & Stone, J. E. (2012b). Still rare like a unicorn? The case of behavioral predatory pricing. Journal of Law, Economics, and Policy, 8(4), 859–882.

Yahya, M. A. (2006). Deterring Roper’s juveniles: Using a law and economics approach to show that the logic of Roper implies that juveniles require the death penalty more than adults. Penn State Law Review, 111(1), 53–106.

Zeiler, K. (2010). Cautions on the use of economics experiments in law. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 166(1), 178–193.

Zeiler, K. (2018). What explains observed reluctance to trade?: A comprehensive literature review. In J. Teitelbaum & K. Zeiler (Eds.), Research handbook on behavioral law and economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Eyal Zamir and all conference participants for helpful comments and suggestions. Special thanks go to my colleague Wendy Gordon for insightful comments and for suggesting the title. Thanks also to Megan Smith-Mady and Erica Puccetti for excellent research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zeiler, K. Mistaken about mistakes. Eur J Law Econ 48, 9–27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-018-9596-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-018-9596-5