Abstract

This paper analyses the determinants of civil litigation in Spain drawing on the Law and Economics approach. Using a panel data for 50 Spanish provinces, this study makes a first exploratory approach to empirically investigate the effect of the 2000 Civil Procedural Law Reform on the demand for civil justice over the period 1995–2010, controlling for other determinants of litigation such as the economic growth, the expansion of the Bar, the number of judges, and other socio-demographic characteristics. According to the results, the growing number of civil cases filed in Spain in recent years seems to be a consequence of the combination of the law reform, relevant socio-economic factors, and most importantly the economic recession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For more details see Sect. 3.

For a briefly review of the literature, see Sect. 2.

See Sect. 4.

See Posner (1992), Cooter and Ullen (1997), Shavell (2004). For a comprehensive analysis of the empirical literature on litigation in civil courts see Kessler and Rubinfeld (2007). A description on the determinants of civil litigation in Spain is presented in Cabrillo and Pastor (2001), and Pastor (2007).

For a recent survey of the literature, see Maclean (2010).

Following Coelho and Garoupa (2006), "In no-fault fault grounds for divorce, divorce proceedings can be initiated without any proof of wrongdoing, neither spouse is considered responsible for the breakup of the marriage, and neither spouse has to prove that the other spouse did something wrong. A fault divorce is one in which one party blames the other for the failure of the marriage by citing wrongdoing. Fault divorce is more common when abuse is a factor. Abandonment, desertion, inability to engage in sexual intercourse, insanity, and imprisonment are other causes for fault divorce".

No-fault rules decrease the costs of getting divorce, so one can intuitively expect an increase in divorce rates. See, among others, Allen (1998), Brining and Buckley (1998), Friedberg (1998), Binner and Dnes (2001), Gruber (2004), Rasul (2006), Coelho and Garupa (2006), González-Val and Marcén (2012), Jiménez-Rubio et al. (2016).

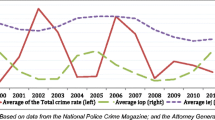

Where Civil Litigation Rate = (civil cases filed ÷ population) * 1000, excluding family cases.

Filed Civil Cases shows the same pattern. See Fig. 2a of Appendix 1.

See Sect. 3.1.

For a comprehensive descriptive analysis of litigation in all jurisdictions in Spain see Pastor (2007).

“[u]n conjunto de instrumentos encaminados a lograr un acortamiento del tiempo necesario para una definitiva determinación de lo jurídico en los casos concretos, es decir, sentencias menos alejadas del comienzo del proceso, medidas cautelares más asequibles y eficaces, ejecución forzosa menos gravosa para quien necesita promoverla, y con más posibilidades de éxito en la satisfacción real de los derechos e intereses legítimos” (Exposición de motivos. Ley 1/2000 de Enjuiciamiento Civil, apartado I.2).

Information about procedures duration is scarce. In Judicial Statistic there is no data disaggregated by courts. The General Council of the Judiciary publishes information about the average length in different jurisdictions in its annual report (The Spanish Judiciary in Figures). The average length of procedures in Civil First-Instance Courts in 1999 was 9.36 months, being 7.7 months in 2010.

When the amount of debt is greater than 6000 euros the process continues through an Ordinary Proceeding.

See Martin-Pastor (2012).

See Djankov et al. (2003) and Mora-Sanguinetti (2010). In Spain, there is no precise information about procedures duration by province. The General Council of the Judiciary publishes every year an approximation to procedures duration based on the information about cases admitted, resolved and in process. Consequently, in this article we don’t analyze the law effects on procedures duration.

For more details on the Judicial Organization in Spain see Garoupa et al. (2012).

Spanish Bar Association (http://www.cgae.es/portalCGAE/home.do).

See Fig. 2c of Appendix 1.

See Posner (1997).

For more details on the legal service markets see Hadfield (2000).

Ginsburg and Hoetker (2006), Buonanno and Galizzi (2014) find that the number of lawyers does exert a positive and statistically significant effect on the litigation rate. Posner (1997) and Clemenz and Gugler (2000) find a positive but no statistically significant effect, while Hanssen (1999) finds a negative and statistically significant effect on the demand for justice.

Spanish Bar Association (http://www.cgae.es/portalCGAE/home.do). For more details about the characteristics of the Spanish market of lawyers see Mora-Sanguinetti and Garoupa (2015).

See Fig. 2d of Appendix 1.

See Fig. 2e of Appendix 1.

See Fig. 2f of Appendix 1.

See Hanssen (1999) who found that population density has a positive and significant correlation with the Annual Civil Filings per 1000 population in Trial Courts. Given that over the period studied the size of provinces have not changed much in Spain, population density actually measures the impact of changes in population. Therefore, we have reported our results using population. Using population density instead does not substantially alter the results.

Family cases have been excluded from the analysis given that to the law passed in 2005 intended to speed up divorce processes (“Express Divorce Law”).

The New Civil Procedural Law was enacted in 2000, but it came effective in 2001.

For log transformed variables the coefficients can be directly interpreted as elasticities. However, for unemployment and education the coefficients can be interpreted as the impact (in percentage terms) of a 1 per cent point increase on education and unemployment.

Under the null hypothesis that regressors are uncorrelated with the error term, the random effects provide more efficient estimates than the fixed effect model.

This is consistent with the findings of Daniels (1982).

Abbreviations

- NCPA:

-

New Civil Procedure Act

References

Allen, D. W. (1998). No-fault divorce in Canada: Its causes and effect. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27, 129–149.

Avraham, R. (2007). An empirical study of the impact of tort reforms on medical malpractice settlement payments. Journal of Legal Studies, 36, 183–229.

Bebchuk, L. (1984). Litigation and settlement under imperfect information. The Rand Journal of Economics, 15(3), 404–415.

Binner, J. M., & Dnes, A. W. (2001). Marriage, divorce and legal change: New evidence from England and Wales. Economic Inquiry, 39(2), 298–306.

Brining, M., & Buckley, F. H. (1998). No-fault laws and at-fault people. International Review of Law and Economics, 18, 325–340.

Buonanno, P., & Galizzi, M. (2014). Advocatus et non Latro? Testing the excess of litigation in the Italian courts of justice. Review of Law & Economics, 10(3), 285–322.

Cabrillo, F., & Pastor, S. (2001). Reforma Judicial y Economía de Mercado. Madrid: Círculo de Empresarios.

Clemenz, G., & Gugler, K. (2000). Macroeconomic development and civil litigation. European Journal of Law and Economics, 9(3), 215–230.

Coelho, C., & Garoupa, N. (2006). Do divorce law reform matter for divorce rates? Evidence from Portugal. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 3(3), 525–542.

Cooter, R., & Rubinfeld, D. (1989). Economic analysis of legal disputes and their resolution. Journal of Economic Literature, 27, 1067–1097.

Cooter, R., & Rubinfeld, D. (1990). Trial courts: An economic perspective. Law and Society Review, 24, 533–546.

Cooter, R., & Ullen, T. (1997). Law and economics. Reading: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.

Daniels, S. (1982). Civil litigation in Illinois Trial Courts. An exploration of rural–urban differences. Law & Policy Quarterly, 4(2), 190–214.

De Andrés Irazabal, C. (comp). (2006). Comentarios a la Ley de Enjuiciamiento Civil, Cinco años de vigencia. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez De Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Courts. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 453–517.

Ellman, I. M., & Lohr, S. L. (1998). Dissolving the relationship between divorce laws and divorce rates. International Review of Law and Economics, 18(3), 341–359.

Farhang, S. (2009). Congressional mobilization of private litigants: Evidence from the Civil Rights Act of 1991. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 6(1), 1–34.

Friedberg, L. (1998). Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 88(3), 608–627.

Garoupa, N., Gilli, M., & Gomez-Pomar, F. (2012). Political influence and career judiciary: An empirical analysis of administrative review by the Spanish Supreme Court. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 9, 795–826.

Ginsburg, T., & Hoetker, G. (2006). The unreluctant litigant? Analysis of Japan’s turn to litigation. The Journal of Legal Studies, 35, 31–59.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2012). Breaks in the breaks: An analysis of divorce rates in Europe. International Review of Law and Economics, 32(2), 242–255.

Gould, J. (1973). The economics of legal conflicts. The Journal of Legal Studies, 2, 279–300.

Gruber, J. (2004). Is making divorce easier bad for children? the long run implications of unilateral divorce. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(4), 799–833.

Hadfield, G. (2000). The price of law: How the market for lawyers distorts the justice system. Michigan Law Review, 98(4), 953–1006.

Hanssen, F. A. (1999). The effect of judicial institutions on uncertainty and the rate of litigation: The election versus appointment of state judges. The Journal of Legal Studies, 28, 205–232.

Jiménez, C., & Pastor, S. (2004). Informe sobre la Justicia Civil. Madrid: Observatorio Justicia y Empresa, Universidad Complutense de Madrid-Instituto de Empresa.

Jiménez, C., & Pastor, S. (2007). Aportaciones sobre Justicia y Empresa. Pamplona: Editorial Aranzadi.

Jiménez-Rubio, D., Garoupa, N., & Rosales, V. (2016). Explaining divorce rate determinants: New evidence from Spain. Applied Economics Letters, 23(7), 461–464.

Kessler, D., & Rubinfeld, D. (2007). Empirical study of the civil justice system. Handbook of law and economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Landes, W. (1971). An economic analysis of the courts. Journal of Law and Economics, 14, 61–107.

Lledó Yagüe, F. (2000). Comentarios a la Nueva Ley de Enjuiciamiento Civil. Madrid: Dykinson.

Lorca Navarrete, A. M. (2000). Comentarios a la Nueva Ley de Enjuiciamiento Civil. Valladolid: Lex Nova.

Maclean, M. (2010). Families. In P. Cane & H. M. Kritzer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of empirical legal research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martin-Pastor, J. (2012). Estudio Estadístico sobre el Éxito de los Procesos Monitorios y su Contribución a la Minoración de los Costes de la Administración de Justicia. Revista de Derecho Procesal, 2, 229–246.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2010). A characterization of the judicial system in Spain: analysis with formalism indices. Economic Analysis of Law Review, 1(2), 210–240.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S., & Garoupa, N. (2015). Do lawyers induce litigation? Evidence from Spain, 2001–2010. International Review of Law and Economics, 44, 29–41.

Paik, M., Black, B., & Hyman, D. A. (2013a). The receding tide of medical malpractice litigation: Part 1—National trends. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 10(4), 612–638.

Paik, M., Black, B., & Hyman, D. A. (2013b). The receding tide of medical malpractice litigation: Part 2—Effect of damage caps. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 10(4), 639–669.

Paik, M., Black, B., Hyman, D. A., & Sage, W. M. (2012). How do the elderly fare in medical malpractice litigation, before and after tort reform? Evidence from Texas. American Law and Economic Review, 14(2), 561–600.

Pastor, S. (1993). ¡Ah de la Justicia! Política Judicial y Economía. Madrid: Civitas.

Pastor, S. (2007). Litigiosidad Ineficiente. In La Sociedad Litigiosa. Cuadernos de Derecho Judicial, 13. Madrid: Consejo General del Poder Judicial.

Pastor, S., & Robledo, J. (2006). Buenas Prácticas en Gestión de Calidad, Información, Transparencia y Atención al Ciudadano. Madrid: Eurosocial.

Posner, R. (1973). An economic approach to legal procedure and judicial administration. The Journal of Legal Studies, 2, 399–458.

Posner, R. (1992). Economic analysis of law. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Posner, R. (1997). Explaining the variance in the number of tort suits across U.S. states and between the United States and England. The Journal of Legal Studies, 26, 477–489.

Priest, G. L., & Klein, B. (1984). The selection of disputes for litigation. The Journal of Legal Studies, 13, 1–55.

Rasul, I. (2006). Marriage markets and divorce law. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 22(1), 30–69.

Rubinfeld, D., & Scotchmer, S. (1993). Contingent fees for attorney: An economic analysis. The Rand Journal of Economics, 24(3), 343–356.

Sanders, J. (1990). The interplay of micro and macro processes in the longitudinal study of courts: Beyond the Durkheimian tradition. Law and Society Review, 241–256.

Shavell, S. (1982). Suit, settlement, and trial: A theoretical analysis under alternative methods for the allocation of legal costs. The Journal of Legal Studies, 11, 55–81.

Shavell, S. (2004). Foundations of economics analysis of law. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce law raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1802–1820.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. London: The MIT Press.

Yoon, A. (2001). Damage caps and civil litigation: An empirical study of medical malpractice litigation in the south. American Law and Economic Review, 3(2), 199–227.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank D. Ildefonso Villán Criado for his valuable help with the Judicial Statistics of the Spanish Council of the Judiciary. We gratefully acknowledge the advice of David Epstein, Sabela Oubiña, and valuable comments made by EJLE referees, Giovanni Ramello, Alessandro Melcarne and participants in the Economic Analysis of Litigation Workshop (Torino, 2015). Authors thank the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology (Research Grants ECO2011-29445 and ECO2010-17049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosales, V., Jiménez-Rubio, D. Empirical analysis of civil litigation determinants: The Case of Spain. Eur J Law Econ 44, 321–338 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9543-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9543-2