Abstract

Despite the consensus about the importance of self-regulated learning for academic as well as for lifelong learning, it is still poorly understood as to how teachers can most effectively support their students in enacting self-regulated learning. This article provides a framework about how self-regulated learning can be activated directly through strategy instruction and indirectly by creating a learning environment that allows students to regulate their learning. In examining teachers’ instructional attempts for SRL, we systematically review the literature on classroom observation studies that have assessed how teachers support their students’ SRL. The results of the 17 retrieved studies show that in most classrooms, only little direct strategy instruction took place. Nevertheless, some teachers provided their students with learning environments that require and thus foster self-regulated learning indirectly. Based on a review of classroom observation studies, this article stresses the significance of (1) instructing SRL strategies explicitly so that students develop metacognitive knowledge and skills to integrate the application of these strategies successfully into their learning process, and (2) the necessity of complementing classroom observation research with data gathered from student and teacher self-report in order to obtain a comprehensive view of the effectiveness of teacher approaches to support SRL. Finally, we discuss ten cornerstones for future directions for research about supporting SRL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite a consensus between educational theory and practice about self-regulated learning (SRL) as a key competency for lifelong learning that learners should acquire from early schooling on (Levin 2003), it is still poorly understood as to how students can best be supported in acquiring this competency to self-regulate their learning. SRL refers to learners planning, monitoring, and controlling one’s learning to make their learning more effective (Veenman 2017). SRL theory is built on the idea that the control of the learning rests with the learner, who regulates his/her actions to achieve a certain goal, such as for example task performance (Paris and Paris 2001). From empirical studies, training studies, experiments, theoretical papers, and meta-analyses can be derived that SRL is positively associated with learning behavior, achievement, and motivation (for an overview, see for example, Dignath and Büttner 2008; Donker et al. 2014; Hattie et al. 1996; Veenman 2013). Studies include all age groups of learners and all kinds of contexts, implying that every student should have the chance to learn how to self-regulate one’s learning. Consequently, every teacher should be able to foster and facilitate SRL among her or his students. Recently, the focus of research on SRL shifted from directly training self-regulation in learners to training teachers in supporting their students’ self-regulation of learning (e.g., Kramarski 2018; Kramarski and Kohen 2017). Despite evidence that teaching can improve SRL (e.g., Perry and Rahim 2011), it is still poorly understood how teachers can enhance SRL most effectively. Moreover, little is known about the teachers’ intentions that guide their different approaches of supporting SRL in the classroom (e.g., Dignath and Büttner 2018).

Self-Regulated Learning

Self-regulated learners plan, monitor, and control their learning in order to reach a learning goal by enacting metacognitive strategies that support these regulation activities (e.g., Veenman 2017). In Nelson’s (1996) metacognition model, students’ learning processes are represented as taking place at two levels. On the object level, the learner’s cognitive activities take place that are needed for the execution of a task. At the meta level, metacognitive activities take place that regulate the object level. As a result of monitoring processes, information about the state of the object level flows to the meta level. Based on the outcome of this monitoring information, regulatory commands from the meta level are transmitted back to the object level through control processes. Nelson’s model describes metacognition as a bottom-up process in which monitoring is activated when interferences in task performance are recognized (Nelson 1996). In order to describe the active use of metacognitive strategies, Veenman (2017) extended Nelson’s model by including the perspective of metacognition as a top-down process. Metacognitive activities are not merely triggered by task interferences (bottom-up), but also by a program of self-instructions at the meta level that is activated once the learner is faced with a more or less familiar problem (top-down). Such self-instructions could take place in terms of condition-action-rules, such as, “IF you encounter a task, THEN look for the task assignment and take notice of it” (Veenman 2017). With regard to Nelson’s (1996) and Veenman’s (2017) models, cognitive strategies are applied on the “executional” object level, while metacognitive strategies are positioned on the “executive” meta level (see Fig. 1). Metacognitive strategies can occur throughout the entire learning process (Flavell 1976). According to Zimmerman (1998), a self-regulated learning process involves three phases: (1) a forethought phase in which learners orientate on the task, set goals, and plan learning activities; (2) a performance phase in which learners monitor for errors and mistakes and for progress being made during task execution; and (3) a reflection phase in which learners evaluate their outcomes and reflect on how to proceed. The learners’ conclusions from this reflection phase may have an impact on their self-concept. The outcome of a learner’s self-evaluation affects a subsequent forethought phase, leading to the cyclical nature of the model. Therefore, the SRL process is illustrated in terms of a feedback loop, involving a cyclical process of evaluating the effectiveness of applied strategies, and reacting to this feedback with motivational, behavioral, or metacognitive responses. Feedback can lead to a change in the perception of the learner’s knowledge or self-esteem, thus affecting the learner’s motivation to further engage in strategic behavior. At the behavioral level, it can result in a modification of the cognitive strategy being used (Zimmerman 1990). In addition, monitoring during the performance phase also contributes to the cyclical nature of SRL (Veenman 2013). When a student struggles in the performance phase, monitoring may incite the learner to re-orient on the task at hand and, thus, return to the forethought phase. The same applies to a negative outcome of evaluation in the reflection phase (Veenman 2013).

During the SRL process, application of metacognitive strategies interacts with motivational processes as well as with the use of cognitive strategies (Boekaerts 1999). The use of cognitive strategies serves to facilitate the execution of the task. Hence, cognitive strategies are considered learner activities that are intended to influence how the learner processes information, for example by summarizing the most important information in a text in order to improve text comprehension (Weinstein and Mayer 1986). As metacognition directs cognitive activities, metacognitive activities cannot take place without carrying out cognitive activities (Veenman 2017). Consequently, it is hard to disentangle cognition and metacognition in learner behavior. For example, a learner who is checking the outcomes of a calculation has taken the decision to do so and to choose this cognitive strategy at the meta level. In this example, orientating oneself in order to understand which cognitive strategy has to be applied, and planning to apply the cognitive strategy of checking one’s outcome, are metacognitive strategies. The execution of the chosen cognitive strategy, however, takes place at the object level (see Veenman et al. 2006). Metacognitive strategies influence the choice of an adequate cognitive strategy and serve to control and monitor the application of this strategy. Whereas cognitive strategies are applied to perform a task, metacognitive strategies are needed to understand how the task has to be performed in an orderly way (Garner 1987). Whether cognitive and metacognitive strategies will be used also depends on the motivational conditions. Motivational processes, such as self-efficacy and goal setting, play a role in SRL by influencing the initiation and maintenance of learning behavior (Efklides 2011). Students who are not motivated for, or who do not see the need for using strategies, are not likely to abide with the instruction of those strategies by their teachers. Applying new strategies may cost students more time and effort than their habitual learning would do. It is therefore important for learners to be motivated to use these strategies (Veenman 2013). The motivation of learners to use cognitive and metacognitive strategies will depend on their metacognitive knowledge, i.e., their knowledge about how and when to use a strategy, their awareness of the benefit of strategy use, as well as on their self-efficacy, i.e., feeling able to use a strategy (Veenman 2011). Thus, SRL arises when knowledge about strategies and the motivation to use strategies co-occur (McCombs and Marzano 1989; Paris and Paris 2001).

The Present Study

In order to derive future directions for research about teachers’ promotion of SRL, we pursue two goals in this review article. Firstly, based on theories about direct strategy instruction and powerful learning environments, we present a framework of direct and indirect approaches to activate SRL. More precisely, we discuss theoretical grounds for different ways of direct strategy instruction and we describe instructional elements of the learning environment that foster students’ SRL in an indirect way. Secondly, we provide an overview of classroom observation research regarding teachers’ support of SRL, since there is evidence as to the validity of score interpretations drawn from classroom observations to assess teachers’ instructional practice (e.g., Brophy 2006; Pianta and Hamre 2009; Schaffer et al. 2014). Combining these two goals may provide new insights into different aspects of teacher practices and their competence to foster SRL in relation to student outcomes. As there is a lack of review studies synthesizing research on teachers’ promotion of SRL quantitatively, this overview does not pretend to present a complete state-of-the-art in the field of teachers’ promotion of SRL. As a conceptual paper, it will review specific studies that have applied classroom observations as a method to assess teachers’ SRL practices, which allows for a better comparison between findings of studies. Based on a review of classroom observation studies, this article stresses (1) the significance of instructing SRL strategies explicitly so that students develop metacognitive knowledge and skills to integrate the application of these strategies successfully into their learning process, and (2) the necessity of complementing classroom observation research with data gathered from student and teacher self-report in order to obtain a comprehensive view of the effectiveness of teacher approaches to support SRL.

A Framework on Teacher Approaches to Activate Self-Regulated Learning

In order to enable and to motivate students to self-regulate their learning, teachers can promote strategies directly, and they can indirectly activate SRL by providing a learning environment that incites students to self-regulate their learning. In the following, we will provide an overview of research that has been conducted to investigate the direct promotion of strategies and the indirect activation of SRL in the school context (see Fig. 2).

Direct Instruction of Strategies

Helping students to self-regulate their learning includes teaching them metacognitive strategies directly (Pressley et al. 1992). Intervention studies in the academic context have shown that SRL can be effectively supported by means of strategy training (Dignath and Büttner 2008; Dignath et al. 2008; Donker et al. 2014; Hattie et al. 1996). In order to support learners in transferring their strategy knowledge to the learning context, the integration of strategy instruction with learning content has been endorsed years ago (e.g., Hattie et al. 1996; Veenman et al. 1994; Volet 1991). Such “embedded” instruction allows students to bring the application of metacognitive strategies in line with task demands by deciding which activity needs to be performed when in the context of a specific task (Veenman 2013). Consequently, extracurricular intervention research has rather been replaced by intervention research that has been integrated within the school context (see Dignath et al. 2008). Such research on strategy instruction can be divided into three lines: In a first line of research, the proximity to real-school context has been increased by providing real classroom teachers with materials to implement strategy training in their classrooms, instead of providing students with extracurricular strategy training. Successful intervention indicated that teachers can effectively promote strategies necessary for SRL after being provided with adequate materials that they can use during their teaching (e.g., Askell-Williams et al. 2012; Leidinger and Perels 2012; Perels et al. 2009). In a second line of research, in-service teachers received training on how to foster their students’ SRL, instead of receiving classroom materials. The aim of this line of research has been to support teachers in preparing their instructional material themselves. Such teacher intervention studies have proven successful in preparing teachers to deliver strategy instruction in their classrooms (e.g., Finsterwald et al. 2013; Kramarski and Revach 2009; Perry et al. 2008; Veenman 2018). A third line of research has integrated SRL intervention into initial teacher training in order to activate preservice teachers’ own self-regulation of learning and teaching, and to implement the promotion of SRL already early in teacher education (e.g., Kramarski and Kohen 2017; Kramarski and Michalsky 2010; Perry et al. 2008; Zohar et al. 2001).

The results of strategy instruction research have indicated that direct strategy instruction can be enacted in various ways that differ substantially in the degree of explicitness (e.g., Dignath and Büttner 2008; Veenman 2011. The distinction between explicit and implicit strategy instruction has been introduced by Brown et al. (1981), who differentiated three levels of strategy instruction: on the lowest level, the so-called blind training, students are induced to use a strategy without providing them with any information about the significance of this activity. The students are not told why to use a certain strategy, in which situations this activity is appropriate, or even that this activity is a strategy. The blind training corresponds with implicit strategy instruction. Although this can enhance the children’s use of the intended activity, it might fail to maintain its production in the future and its generalization to similar useful contexts. On an intermediate level, the informed training, students are both induced to apply a certain strategy, but are also provided with information about the significance—i.e., benefits or usefulness—of this strategy (Veenman 2013). This type of training should result in improving the performance, as well as in maintaining this activity when faced with a similar subsequent problem. And finally, the self-control training, the highest level of instruction, combines the informed training with an explicit instruction of how to manage, monitor, check, and evaluate strategy application. This type of training best facilitates the transfer of strategy application to appropriate settings (Brown et al. 1981; Veenman 2018). Informed and self-control training help students to execute and maintain particular metacognitive strategies, with self-control training making students more flexible in applying the strategies to various contexts (Brown et al. 1981). Thus, explicit instruction means that the teacher clearly instructs the students about a strategy by explaining and demonstrating how to execute a particular strategy, clarifying benefits of strategy use, and supporting students in strategy application (see Table 1). This is referred to as the WWW&H rule for strategy instruction, denoting What to do, When, Why, and How (Veenman 2013; Veenman et al. 2006). The teacher provides students with information about the application of a certain strategy in order to help them develop metacognitive knowledge (e.g., Dignath and Büttner 2008; Dignath-van Ewijk et al. 2013).

Implicit instruction can be an effective way of stimulating strategy use once students are already experienced in using a certain strategy (see Table 2). However, students first have to be trained in self-regulation strategies explicitly in order to benefit from implicit instruction and modeling (Harris et al. 2013; White and DiBenedetto 2015). However, research has shown that the instruction of learning strategies does not necessarily improve learning outcomes, strategy use, or motivation. Students also need to receive feedback on their strategy use (Zimmerman 2002), and they need to have metacognitive knowledge about strategies and to reflect on the benefit of using them in order to be able to successfully apply them (Schraw 1998; Veenman et al. 2006). The outcomes of meta-analytic research have demonstrated that enabling learners to reflect on their use of metacognitive strategies leads to larger effects of strategy training (Dignath et al. 2008; Dignath and Büttner 2008; Donker et al. 2014; Hattie et al. 1996). Such metacognitive reflection about strategy use includes two aspects, as learners (1) need to master the skill of applying a learning strategy, and (2) need to have the will to engage in SRL (McCombs and Marzano 1990). (1) More precisely, this means that in order to develop the skills for SRL, learners need to acquire metacognitive knowledge. Thus, they need information about how to use strategies, and about conditions under which a certain strategy is most useful in order to learn the skill (e.g., Butler 2002; Schraw 1998). Through explicit instruction, teachers help students to reflect about their own strategy use on a meta level (see Nelson 1996), and to apply strategies in an effective way (see Veenman 2017). Reflecting on strategy use can also help to transfer the application of a certain strategy to another task or even another subject area (Veenman 2018). (2) Additional to metacognitive strategy knowledge, students need to learn how they benefit from using a certain strategy, thus, to build up a motivation for using strategies. Investing additional time and effort for strategy use requires motivation from the learner (Efklides 2011). This is more likely to happen once students know that it will help them to save time and improve their performance. Once students are prepared for SRL, they need learning environments that allow them to enact and practice SRL (e.g., White and DiBenedetto 2015).

Indirect Activation of SRL

Beside the intervention research on how to instruct strategies, another field of research has been investigating how SRL can be fostered in a subtler way than through direct strategy instruction, namely by creating learning environments that require learners to self-regulate their learning, without providing strategy training (e.g., Perry and Rahim 2011). As SRL draws on social-constructivism, one can assume that learners actively take part of their learning process by constructing their knowledge (Zimmerman 2000). Providing students with constructivist learning environments is therefore essential in helping students to become self-regulated learners (e.g., Hmelo-Silver et al. 2007). A framework for learning environments, which are strongly related to the indirect encouragement of SRL, has been described by De Corte et al. (2004), who derived four aspects of learning environments from constructivist learning theory: (1) activating prior knowledge & creating cognitive conflict, (2) learning in context, (3) cooperative learning, and (4) self-directed learning. In the following, we will show how these aspects are grounded in educational and psychological learning theory, and how they relate to the activation of SRL.

-

(1)

In order to stimulate SRL, learning cannot take place in a passive and receptive way, but through an active construction of associations with one’s prior knowledge (Limón 2001). Prior knowledge is essential for learners to understand the task and the goals of the task (Eilam and Aharon 2003). In this way, the activation of prior knowledge facilitates the learner to monitor (Butler and Winne 1995), and to formulate challenging goals (Dembo and Eaton 2000). In order to encourage active participation in knowledge construction, research has shown that students should work on complex, less structured, or open problems, which can be solved only through a deeper understanding of the topic (Dolmans et al. 2005).

-

(2)

In addition, SRL can be supported when the situatedness of learning is taken into account by providing learning situations that highly correspond to the application (Resnick 1987). Learning situations are often more theoretical and abstract compared to situations of application. This increases the effort of the learner to transfer the knowledge from the learning situation to a real-life application of the knowledge. Therefore, knowledge often remains inert (Renkl et al. 1996). Hence, the situatedness of the learning situation is initially needed for the acquisition of knowledge. Next, the acquired knowledge should be abstracted and detached from the context in which it was initially learned, which serves as a basis of transfer (Salomon and Perkins 1989).

-

(3)

SRL can also be supported by providing cooperative learning environments that stimulate students to exchange about different perspectives toward the learning content (Vosniadou et al. 2001); for example, Jigsaw (Aronson 1978), or Student Teams-Achievement Divisions (STAD; Slavin 1995). Research has shown that cooperative learning can facilitate learning, and in particular SRL (e.g., Souvignier and Mokhlesgerami 2006), especially in complex tasks that produce a high cognitive load. The cognitive resources of several learners can share the burden of the load (Kirschner et al. 2009). Over the last 15 years, new models of socially shared regulation of learning (SSRL; Hadwin et al. 2011; Molenaar et al. 2011) have added the description of social processes to the individual process of SRL. Additional to regulation of task performance, SSRL describes regulatory processes within the interactions between the group members (for a review, see Panadero and Järvelä 2015).

-

(4)

Finally, a student-directed learning environment enables students to participate in the planning, selection, and accomplishment of learning activities (Perry and Rahim 2011). Self-determination flourishes when a more or less structured learning environment allows for effective autonomy in students (Deci and Ryan 1985, 1993). Thus, internal control by the student and external control by the teacher should be balanced. To enable self-determination in students, teachers alternate between guiding through direct instruction and coaching when needed (White and DiBenedetto 2015). In the latter capacity, they monitor the adequacy of student decisions, and they are available for consultation when students face problems. Instructional elements—such as individualized instruction, working with weekly schedules, problem-based learning on projects, or interdisciplinary learning—can offer opportunities for self-determination (Van de Pol et al. 2010).

In line with these approaches to activate SRL indirectly, Perry’s research (e.g., 1998; 2013; 2015) has demonstrated that there are several instructional elements of learning environments that are relevant for students’ engagement in SRL: (a) offering complex and meaningful activities; (b) providing choices about the content, the place, or the cooperation partner while working on an assignment; (c) providing choices about the level of challenge, i.e., about how much to do, at what pace, and with what level of support; and (d) providing evaluation criteria. These instructional elements have proven to distinguish between classrooms that support students in enacting SRL and those that do not (e.g., Perry et al. 2002, 2006). For example, Butler et al. (2013) supported teachers in using more inquiry-oriented or problem-based learning approaches in order to engage their students in authentic learning tasks. This should provide the foundation for students to integrate both content and process learning. They found student achievement gains to be associated with teachers who stimulated independence during learning through inquiry-oriented and problem-based learning (Butler et al. 2013). Contrary to the research area on strategy training described above, these studies did not focus on direct strategy instruction, but on an indirect support of SRL by creating conditions conducive for SRL (see Table 3).

Drawing on research of the instructional quality of classroom teaching, the here-mentioned instructional elements, which are conducive to SRL, can be traced back to generic models of teaching effectiveness that have been derived from meta-analyses (e.g., Scheerens et al. 2007; Seidel and Shavelson 2007), and from longitudinal student assessment studies (e.g., Hiebert et al. 2003; Klieme et al. 2009). Although the support of SRL is not explicitly in the focus of research on high-quality instruction, most frameworks of teaching effectiveness embrace similar concepts, characterized by organizational, social, and instructional processes (Eccles and Roeser 2010), or by teaching decisions regarding classroom management, motivational atmosphere, and curriculum and instruction (Pressley et al. 2001). In line with this categorization, Hamre and Pianta (2009) presented the CLASS framework (Classroom Assessment Scoring System; Pianta et al. 2008) that includes three domains: classroom organization, emotional support, and instructional support. Similarly, Klieme et al. (2009) derived three basic dimensions of teaching quality—classroom management, student support, and cognitive activation—from the data of the TIMSS and PISA studies (see also Praetorius et al. 2018). Classroom management covers how a teacher handles classroom disruptions, discipline, and clarity of rules by identifying and strengthening desirable student behaviors, and preventing undesirable ones (Kounin 1970). Through classroom management, teachers can create effective learning opportunities that enhance time on task (e.g., Seidel and Shavelson 2007) and student motivation (e.g., Rakoczy et al. 2007). Thus, classroom management can be seen as a precondition for the enactment of the constructivist instructional elements mentioned earlier that support SRL. Secondly, teachers’ student support builds on research about classroom climate and social interactions, as well as about teachers’ adaptive support of the learning process (i.e., their diagnostic competence, a positive culture of errors, and individual learning support (Praetorius et al. 2018)). As shown earlier, scaffolding plays an important role in fostering students’ SRL (see Collins et al. 1991). Finally, among the three dimensions, cognitive activation is most closely aligned with the above-mentioned instructional elements to activate SRL. Following constructivist theories of learning, cognitive activation aims at enhancing conceptual understanding as well as students’ engagement with the learning content (e.g., Hiebert et al. 1997) by exploring and building on students’ prior knowledge, by stimulating cognitive conflict, by activating higher-order thinking processes, and by fostering students’ metacognition (e.g., Baumert et al. 2010). Although little research has been carried out to date that has brought together general features of teaching quality with SRL, the few studies available have indicated that these three dimensions of teaching quality are associated with students’ SRL (Rieser et al. 2016), and—inversely—that a professional development course for teachers about promoting SRL not only affects specific instructional elements for SRL but also generic teaching quality (Werth et al. 2012).

Developing Self-Regulated Learners

Several researchers have provided suggestions to support the development of self-regulating learners that can be distinguished in their degree of how explicit the activation of regulation strategies takes place. Most models have in common that they assume the teachers’ efforts in supporting the students to change over time are in accordance with the developmental level of the students (e.g., Schunk 2008; White and DiBenedetto 2015; Zimmerman 2002). Such adaptive scaffolding has been described by Collins et al. (1991), who differentiated among four different aspects of apprenticeship that can serve to instruct strategies: modeling, scaffolding, fading, and coaching (Cognitive Apprenticeship; Collins et al. 1991). In modeling, the students watch the teacher using a certain strategy. The student learns to use the strategy by observing the teacher in terms of modeling (Bandura 1986). Scaffolding implies that the teacher adapts his or her support to the needs of the student who is carrying out a task. In fading, the teacher slowly removes his or her support and gives more and more responsibility to the student. Finally, coaching comprises the whole process of apprenticeship instruction, including the choice of tasks, providing students with hints, scaffolding, giving feedback, and structuring the procedures of the learning process. In the same vein, Zimmerman (2000, 2002)) describes four levels of self-regulation that teachers use in order to support students’ development of SRL: (1) At the observation level, teachers control the pacing of the learning by demonstrating and verbalizing regulatory actions and thoughts. (2) At the emulation level, the students attempt to follow the behavior that has been modeled by their teacher or peer. At this stage, it is the teacher’s role to support and encourage the student and to provide feedback. (3) When students proceed to practice what was learned without further input by teachers, they have entered the level of self-control. At this level, teachers can provide learning environments that allow the students to gradually take over responsibility for their learning and to deliberately practice the use of a learning strategy. (4) At the self-regulation level, the students monitor their behavior, and are able to adjust their learning systematically to changing requirements and conditions. Now the teacher can offer a learning environment that allows the students to perform without teacher supervision, and only provides assistance when requested (Zimmerman 2000, 2002). Both approaches have in common that teacher control of the learning process is reduced as students move to the next self-regulatory level (see also Salonen et al. 2005). Observational learning is supposed to be guided and scaffolded by the teacher (White and DiBenedetto 2015). Nevertheless, the modeling of strategy use can take place implicitly if the teacher supports the student in learning SRL without explicitly addressing strategy use. In this regard, implicit means that the teacher demonstrates a procedure without verbalizing what he or she is doing or without mentioning why a certain strategy is useful. The teacher does not necessarily provide the students with metacognitive information about strategy use and its benefits during modeling. Examples of implicit strategy instruction can be found in Table 1. Modeling, scaffolding, fading, and coaching can be implicitly used, but they may become explicit once the teacher addresses metacognitive aspects of strategy use. Regarding such adaptive scaffolding, there is a consensus that learners first need to learn regulation strategies before they can regulate their learning effectively (Corno 2008). The more students are trained in using self-regulation strategies, the more teachers need to provide learning opportunities that allow students to practice self-regulation. After modeling or observation, students will deliberately practice how to apply regulation strategies. This first take place under the supervision of their teachers, but teachers will gradually fade their scaffolding (Perry and Rahim 2011). The concepts of such constructivist principles require some guidance, at least for learners who are not experienced in self-regulation yet. Complex learning environments that contain much information, but only minimal structure or guidance, will be detrimental for learning since they increase cognitive load (Kirschner et al. 2006). There is evidence that metacognitive support can prevent students from experiencing high cognitive load (e.g., Kuensting et al. 2013), and that constructivist learning environments, such as problem-based learning, are more effective for learning when they provide explicit guidance (Wijnia et al. 2014).

Most research on teachers’ support of SRL has focused on either direct or indirect activation of SRL, although the models of learners’ SRL development described above imply that both are interacting in order to support students’ SRL adaptively (see also Pressley et al. 1992). Based on the framework presented here, we will provide empirical evidence about teachers’ attempts to foster SRL by considering both, direct and indirect approaches of teachers’ SRL practice. To this aim, we review the literature on classroom observation studies about teachers’ direct and indirect instructional practice to support SRL.

Classroom Observations of Teachers’ Approaches to Foster Self-Regulated Learning

The second aim of this paper is to systematically review classroom observation research focusing on teachers’ activation of SRL and to provide an overview of the field. Studies conducted to investigate teaching practice are usually based either on teachers’ self-report or on classroom observation methods. Regarding teachers’ SRL practice, self-report consists mainly of teacher questionnaires that assess how teachers perceive their teaching for SRL (e.g., Lombaerts et al. 2009). Although questionnaires can be administered economically to large groups, and their analyses are efficient regarding time and costs, off-line self-reports can suffer from validity problems (see Veenman 2011, or Veenman and van Cleef 2019 for an overview): First, teachers have to reconstruct their earlier teaching behavior from memory, and their retrieval might fail or be biased. Second, the administered questions might evoke biased answers, either due to social desirability, or because the described teaching behavior might create an illusion of familiarity. And finally, teachers have to value certain teaching activities by comparing themselves to other teachers, but they might vary in the reference point chosen for doing so. The latter likely impedes the comparability of results across teachers, and even within one teacher across several measurement points (Veenman and van Cleef 2019). Thus, self-report data alone has proven insufficient when attempting to understand the complex interplay of SRL in real classroom contexts (Perry and Winne 2006). As an alternative, classroom observations offer more suitable ways to capture teachers’ instructional practice to support SRL (Butler 2002; Perry 2002; Perry et al. 2002). Contrary to offline measures, observations are not relying on introspection and the associated validity problems (Veenman and van Cleef 2019). Classroom observations, however, are also subject to certain limitations. Like other online assessments, they are time-consuming, which hinders the assessment of a larger teacher sample. Moreover, observations only capture the overt behavior, but not the underlying mental processes (Veenman and van Cleef 2019). For instance, Dignath and colleagues (2013) have shown that classroom observations about teachers’ SRL practice were not necessarily associated with teachers’ or students’ estimation about their SRL practice, but teachers overestimated their SRL practice compared to observations and student ratings. Consequently, teachers might have different teaching intentions than what becomes overt in their teaching behavior, and these intentions are not captured by observations only (Dignath et al. 2013). Yet, observations show what teachers actually do in their lessons. Accordingly, classroom observation seems a suitable method to assess teachers’ approaches to foster SRL, but it restricts the sample size and requires supplementary assessment of teachers’ mental processes. To prevent the validity problems associated to self-report data, we restricted our review to studies that have applied classroom observations to assess teachers’ SRL practice. In order to advance research about teachers’ promotion of SRL, this systematical review addressed the following research questions:

(1) How do teachers attempt to promote SRL among their students?

(2) How is teachers’ SRL practice related to student outcomes?

(3) Which teacher characteristics predict teachers’ SRL practice?

Method

Eligibility Criteria

The literature search was restricted to studies that met the following eligibility criteria: Firstly, articles had to provide empirical data from classroom observations focusing on teachers’ SRL practice, as well as quantitative or qualitative analysis of this observation data. Secondly, studies had to be based on theoretical models of SRL or metacognition. Thirdly, studies were to be conducted in an educational setting, such as kindergarten, primary or secondary school, compulsory education, or higher education. Finally, the article’s purpose had to be to investigate teachers’ SRL practice.

Literature Search

Our search was conducted in the databases PsycInfo, ERIC, and Google Scholar, and we combined the keywords teacher, classroom observation, and self-regulated to search for in the whole article. We included recent literature published in the last three decades, as the most cited models of SRL have been published since the year 1990 (see Panadero 2017). Thus, we restricted our search to studies published between 1990 and 2019. Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals as well as in English language were included in the review. The initial search produced 3710 hits that were scanned based on title and abstract whether they meet the eligibility criteria. From this first screening, 20 studies were considered for meeting the criteria and were submitted to a more systematic coding. To this end, we read the whole article in order to decide whether the study was suitable. This more systematic sorting delivered 17 studies that used systematic observation methods to investigate teachers’ attempts to foster SRL and provided quantitative or qualitative data. Other studies had to be sorted out for several reasons. Some articles did not provide data about classroom observations needed for our analyses (e.g., Lau 2012); others did not focus on the SRL of the learners, but instead of preservice teachers’ own SRL (e.g., Buzza and Allinotte 2013), or the classroom observation addressed students’ SRL instead of teachers’ promotion of SRL (e.g., Housand and Reis 2008). This relatively small amount of classroom observation studies in SRL research can be attributed to the high costs of (mostly video-based) observations. Contrary to the research field of teaching effectiveness, where video-based classroom observation has been established successfully as a research method (e.g., Hiebert 2003; Hugener et al. 2009; Stigler et al. 2000), self-reports are the primary tools applied to assess SRL and SRL practice (Dinsmore et al. 2008; Perry and Rahim 2011). The 17 retrieved observation studies were based on different conceptual models (e.g., models on SRL, such as Zimmerman (2000), or models on metacognition, such as Verschaffel et al. (1999), were conducted in different school contexts (primary and secondary school; in-service and preservice teachers), in the context of various school subjects, and focused on different instructional approaches. In accordance with the presented framework, these approaches of studies focused on direct strategy instruction, on indirect activation of SRL, or a combination of both approaches.

Method of Analysis

Following the guidelines by Aveyard (2014), we first derived codes in order to systematically analyze the retrieved studies. To this end, all papers were re-read more in depth, and the following information was coded and provided in a review table (see Table 4 and Table 5). Theoretical model, observation instrument, coding categories of observation instrument, student population, content area (school subject), number of observed teachers, number of observed lessons, number of students, multiple data assessment, main findings, more specifically, findings about direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of SRL, as well as strengths and limitations of the study. In the second step, related codes were grouped together into four themes: conceptual information (theoretical model, observation instrument, coding categories), contextual information (student population, content area, number of teachers and lessons), methodological information (multiple data assessment, strengths, and limitations), and main findings. In the third step, we addressed the four identified themes when discussing each of the three research questions.

Results

General Description of the Studies

The included observation studies have been carried out in a range of countries (Belgium, Canada, Germany, Hong Kong, USA, Switzerland, The Netherlands), and involved in total 541 teachers and 2318 students. Most of the observation studies have been conducted in the context of mathematics (k = 7), while other studies included several subjects with mathematics being part of (k = 6), writing (k = 3), or physics (k = 1). Seven studies investigated primary school classrooms, and 11 investigated secondary school classrooms. On average, a study was based on M = 3.44 classroom observations, while most studies included only single lessons, and only one study was based on 7-month-long weekly observation (Depaepe et al. 2010). Except for Spruce and Bol (2015), all coding of strategy instruction was based on low-inferent ratings of short time intervals (30 s to 1 min) in order to capture teaching time relevant to the instruction of metacognitive strategies. Ratings for the indirect activation of SRL were usually based on high-inferent ratings (e.g., Perry 1998; Michalsky and Schechter 2013).

How Do Teachers Attempt to Promote SRL Among Their Students?

Classroom observation studies differed in their focus on either direct strategy instruction, or indirect activation of SRL, or a combination of both. In the following, the results of this review that addressed teachers’ promotion of SRL will be sorted according to the framework presented above.

Teachers’ Direct Strategy Instruction

As one of the first classroom observation studies about teachers’ attempts to support students’ ways of learning, Moely et al. (1992) investigated the direct strategy instruction of 69 primary school teachers and how this varied as a function of grade level and school subject. As their study was built on models of strategy instruction they assessed teachers’ instruction of metacognitive strategies and of cognitive strategies in language arts and math classrooms, as well as in mixed subjects. The observations yielded that teachers’ suggestion of strategy use occurred only in 2% of the observed intervals. As not all of the strategies that Moely et al. (1992) coded were metacognitive, but rather cognitive (e.g., rote learning), the amount of metacognitive strategy instruction was even smaller. With regard to the activation of metacognitive reflection about learning, they found that only in less than 1% of the observed intervals did teachers provide rationales for strategy use. Only 19 instances were coded for teachers instructing pupils in the generalization of strategies. Finally, 10% of the observed teachers gave no strategy suggestion at all (Moely et al. 1992). Moely et al. (1992) found a significant interaction between grade level and strategy instruction: significantly more strategy instruction was observed in second and third grade than in kindergarten and first grade or in fourth through sixth grade. In a second study, they investigated differences in student performance as a function of teachers’ strategy instruction (Moely et al. 1992). These results will be reported on in the next chapter. In an observation study in middle school classrooms, Hamman et al. (2000) adapted the coding scheme by Moely et al. (1992) and extended the coding of teachers’ suggestions of strategy use by the types and frequency of what they called “teachers’ coaching of learning”, which referred to teachers’ description of cognitive processes to complete a task, suggestions for strategy use, and explanation of a rationale for why the strategy might be effective. For the 11 middle school teachers who were observed, teaching math, science, English, and social studies in grade 6, 7, or 8, coaching of learning was not found to vary as a function of class grade, school subject, or instructional phase. In line with Moely’s observations in primary school classrooms, Hamman et al. (2000) found only 2% of the instruction segments in middle school to consist of teachers’ strategy instruction. While most of the strategies addressed by teachers were cognitive in nature (e.g., rehearsal), only 0.40% of the total instruction was spent on the instruction of metacognitive strategies, and 0.05% on the instruction of time management strategies. In addition to classroom observations, Hamman et al. (2000) combined the teacher observations with their students’ self-reported strategic learning activity, which will be presented in the next chapter. In line with the results of Moely et al. (1992) and Hamman et al. (2000), Veenman et al. (2009) found similarly low amounts of teaching time devoted to the instruction of metacognitive strategies in secondary school classrooms. They observed a sample of 17 middle school classrooms taught by seven teachers in different disciplines with regard to their instruction of metacognitive strategies. Although a few teachers showed multiple implicit strategy use in their lessons, teachers devoted only 4% of their teaching time to explicit metacognitive strategy instruction. Moreover, strategy instruction focused on orientation and planning, rather than on monitoring and evaluation (Veenman et al. 2009). The study by Zepeda et al. (2019) aimed at analyzing teachers’ metacognitive strategy instruction and at combining this with data of students’ learning activity. To this end, they re-analyzed video- and student data that had been gathered in the scope of the MET study (METLDB; Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation 2010) in classrooms from grade 6 through 8. Next to the instruction of metacognitive strategies, Zepeda et al. (2019) differentiated between metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive strategies to be addressed by the teacher. Their results yielded that only 7% of the teachers’ talk was related to support of metacognition. Furthermore, support of metacognition took place almost five times more often during whole-class instruction than during individual learning phases. Moreover, across all classrooms, teachers supported more monitoring and evaluation than planning; and more personal metacognitive knowledge was addressed than strategy knowledge or conditional knowledge. With regard to teachers’ instructional activity when addressing metacognition, more than 80% of all instructional manners were prompting, but still more directives were provided by teachers than modeling statements. In order to examine how teachers’ metacognitive talk is related to class learning outcomes, Zepeda et al. (2019) compared the metacognitive talk of teachers’ in low- and high-conceptual growth classrooms (see next chapter). In the same vein, Depaepe et al. (2010) analyzed teachers’ instruction of metacognitive strategies as well as their statements about metacognitive knowledge. However, rather than analyzing the classroom observations of a single lesson of many teachers, they chose for an in-depth design. In addition to weekly observations in two sixth-grade mathematics classroom for a 7-month-long period, they conducted interviews with the two observed primary school teachers, and assessed the students’ problem-solving skills and their mathematics performance. The classroom coding was based on the metacognitive model for solving mathematical problems by Verschaffel et al. (1999). With regard to metacognitive knowledge, Depaepe et al. (2010) also coded separately what to do, how, and why. In line with Zepeda et al. (2019), Depaepe’s results revealed that the planning phase was hardly addressed in both teachers’ instructional approaches. In general, teachers did not refer to the how and the why aspects of strategy use. Depaepe et al. (2010) found strong differences in the teachers’ intensity of referring and using the metacognitive model, which was also reflected in the teachers’ own understanding of their classroom practice (teacher interview) as well as in a significant difference between their students’ rating of each teacher’s use of the metacognitive model during mathematics lessons. Although these results have been based on a very small sample of two teachers and can thus not be generalized, this study produced highly internally valid results as the classroom observations have been conducted over a very long time period of 7 months, and because the data on teachers’ promotion of SRL has been triangulated with teacher interviews and student ratings. Moreover, pre- and posttests have been conducted in order to investigate effect of teachers’ SRL practice on students’ learning progress. These results will be discussed in the next subchapter regarding the second research question. In a similar study, Spruce and Bol (2015) combined classroom observations and teacher interviews to investigate the instructional practice of ten primary and secondary school teachers with regard to their support of SRL. Drawing on Zimmerman’s process model of SRL and on the regulatory checklist by Schraw (1998), Spruce and Bol (2015) distinguished between teachers’ instruction of metacognitive strategies during the planning phase, the monitoring phase, and the evaluation phase of the SRL cycle. They coded whether, and how often and strongly teachers referred to or directed the activity for such a strategy. The observed teachers activated most SRL among their students during the monitoring phase of learning, but hardly during the planning phase, and even less during the reflection phase of the learning cycle. Moreover, they observed only little direct instruction of metacognitive strategies in the participating classrooms (Spruce and Bol 2015).

Teachers’ Indirect Activation of SRL

Whereas the observation studies described above have investigated the amount of teaching time that teachers devote to metacognitive strategies, other observation studies have focused on the instructional elements that teachers use to activate SRL indirectly. Among the first who investigated the learning environment in real classroom that offer opportunities for SRL, were Perry and her colleagues (Perry 1998; Perry and VandeKamp 2000; Perry et al. 2002, 2006). Perry’s (1998, 2000) observation scheme included seven categories that distinguish high- and low-SRL environments when coding teachers’ speech and actions: (1) types of tasks, (2) types of choice, (3) opportunities to control challenge, (4) opportunities for self-evaluation, (5) support from the teacher, (6) support from peers, and (7) teachers’ evaluation practices. The presence and quality of each category in an observed activity were rated on a three-point rating scale (Perry and VandeKamp 2000). The observation studies conducted by Perry showed that three of the five observed primary school teachers provided many learning opportunities to their first- and second-grade students, which activated SRL. In particular the complexity of tasks was often associated with the opportunities for students to engage in SRL. These teachers provided their students with complex, cognitively demanding activities, and with the explicit instruction and extensive scaffolding of self-regulation strategies. Likewise, their students were capable of motivating themselves and of regulating their writing process (e.g., Perry and VandeKamp 2000). Perry et al. (2006) expanded Perry’s observation research by investigating whether and how preservice teachers can be mentored to design tasks and develop practices that foster SRL in primary school students. To this end, they reported the results of the first 2 years of a 4-year long intervention study with dyads consisting of 37 preservice teachers and their 37 mentors. Classroom observations indicated that many preservice teachers were capable of designing tasks and implementing practices conducive to SRL. Moreover, the complexity of the tasks was strongly predictive of opportunities for students to develop and engage in SRL (Perry et al. 2006). Focusing on classrooms for older students, Bolhuis and Voeten (2001) conducted classroom observations to investigate how secondary school teachers enacted their teaching with regard to process-oriented teaching for SRL (Vermunt and Verschaffel 2000). Among the 68 secondary school teachers, who had each been observed twice in grade 10–12 classrooms, more than 40% of the teaching time was spent on activating students to work independently, while only 5% of the total amount of time was spent on process-oriented teaching, i.e., explaining, asking questions, giving feedback concerning the learning process, and providing students with strategies for SRL. Accordingly, most teachers provided their students with learning environments that required SRL, but only little activation of SRL was observed. Bolhuis and Voeten (2001) stress the general problem that “it seems that students just have to be more independent, but that they are not explicitly taught how to manage this autonomy” (Vermetten et al. 1999, p. 3).

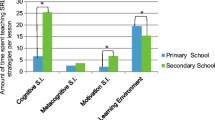

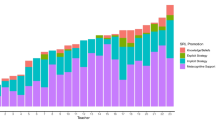

Teachers’ Direct Strategy Instruction and Indirect Activation of SRL

While the studies presented earlier focused on either direct strategy instruction or indirect activation of SRL, some classroom observation studies explored teachers’ direct instruction of strategies as well as their indirect activation of SRL by providing their students with learning opportunities that foster SRL. These studies can offer new insights into the interplay between both—the direct instruction of metacognitive strategies and the learning opportunities that allow students to self-regulate—and allow investigating when teachers apply which approach to foster SRL, and, ideally, how this is related to student outcomes. Kistner et al. (2010) investigated secondary school teachers’ promotion of SRL by re-analyzing 20 video-taped mathematics classrooms from the Swiss-German TIMSS video study (Klieme et al. 2009). The results revealed that on average, only one-tenth of all observed strategy instructions during a lesson focused on metacognitive strategies. The overarching part of incidents, in which teachers addressed strategies, referred to cognitive learning strategies (Kistner et al. 2010). Another study that investigated teachers’ direct and indirect promotion of SRL and its associations with student outcomes was conducted by Dignath-van Ewijk et al. (2013), who observed how secondary school teachers fostered SRL in 17 seventh-grade mathematics classrooms and investigated how their activation of SRL would predict their students’ achievement, and also their students’ SRL. Like the results by Kistner et al. (2010), the largest part of incidents, wherein teachers addressed strategies, was related to cognitive learning strategies, which were closely linked to the learning content of the lessons. Moreover, the instruction of cognitive strategies took place more than six times more often than the instruction of metacognitive strategies. Additionally, the amount of teachers’ explicit strategy instruction was so small that no differentiation in the coding procedure had been possible; thus, Dignath-van Ewijk et al. (2013) only reported implicit strategy instruction. Next to teachers’ direct—though implicit—strategy instruction, Dignath-van Ewijk and colleagues (2013) investigated how teachers designed their learning environment, revealing that teachers scored only low on cooperative, situated, and problem-based learning, and only reached higher ratings regarding the activation of prior knowledge. Furthermore, teachers were significantly more positive than students and observers about their promotion of SRL, scoring up to one rating point higher than the students on a six-point Likert scale. Despite the different estimation of the level for teachers’ SRL practice, for almost all areas, teacher and student ratings correlated significantly, whereas teacher and observer data turned out not to be associated significantly (Dignath-van Ewijk et al. 2013). In another classroom observation study, Dignath and Büttner 2018) compared primary and secondary school teachers’ support of SRL in a video study with 28 mathematics classrooms. Again, altogether most teachers spent substantially more time on the instruction of cognitive strategies than that they addressed metacognitive strategies, and hardly any explicit strategy instruction could be observed. As the results demonstrated, primary and secondary school teachers did not differ in the amount of time spent on addressing metacognitive strategies per lesson. However, in the seventh-grade secondary school classrooms, substantially more support of cognitive and of motivation strategies was observed than in the third-grade primary school classrooms. Conversely, the primary school teachers scored higher with regard to their indirect activation of SRL, mainly regarding the use of cooperative learning and of constructivist elements of teaching Dignath and Büttner (2018) conclude that while the results indicate that teachers acknowledge SRL somehow, the explicitness of strategy instruction is still missing in regular classrooms. Moreover, the results suggest that teachers address SRL differently in primary and secondary school classrooms. Since the data is correlational, no conclusions can be drawn about whether teachers think that self-regulation is rather for older students, or whether they adapt their strategy instruction to the skills of their students. Nevertheless, the instruction of metacognitive strategies is mainly lacking in both age groups (Dignath and Büttner 2018). Michalsky and Schechter (2013) used classroom observations in order to evaluate the effectiveness of a professional development course during the practicum phase of 124 preservice teachers training. For this review, we were only interested in the baseline measure of all groups that took place prior to the intervention. The preservice teachers spent less than 3% of the lesson on the explicit instruction of metacognitive strategies, but twice as much on the implicit instruction of metacognitive strategies. The participants spent slightly more time on the instruction of motivation and cognitive strategies. Altogether, only little explicit strategy instruction was observed. Concerning the indirect activation of SRL, the classroom observations revealed that the preservice teachers applied cooperative learning methods to a certain extent, but they did not provide a very constructivist or student-directed learning environment, and did not specifically account to foster transfer of learning (Michalsky and Schechter 2013). Combining the results of these four observation studies reveals that in-service and preservice teachers had comparably low scores regarding their indirect activation of SRL, promoted strategies rather implicitly, and mainly focused on the instruction of cognitive strategies compared to motivation strategies or metacognitive strategies, although the amount of time spent on cognitive strategy instruction was substantially higher in the mathematics classrooms of the observed in-service teachers (see Dignath-van Ewijk et al. 2013; Dignath and Büttner 2018; Kistner et al. 2010) than in the science classrooms of the observed preservice teachers (Michalsky and Schechter 2013). This difference could be due to teachers’ experience, but also due to the observed school subject, as mathematical learning content often includes mathematical heuristics, thus cognitive strategies.

How Is Teachers’ SRL Practice Related to Student Outcomes?

In order to address this research question, in some of the reviewed studies, additional student data of the observed teachers had been gathered (e.g., Hamman et al. 2000), while others divided classrooms into two groups, either based on student or teacher characteristics, and compared teachers’ SRL practice as a function of students’ learning gains (e.g., Zepeda et al. 2019) or students’ performance as a function of teachers’ SRL practice (e.g., Moely et al. 1992). To this end, Moely et al. (1992) investigated whether students’ performance in a memory task would vary as a function of their 25 teachers’ low or high tendency to suggest strategic activities during learning. The results showed that for high achieving children, the amount of teachers’ strategy instruction did not affect their results in the memory task; they benefitted from a short training session for the recall task and showed a good memory task performance in the posttest. However, for the group of low or moderate achievers, children whose teachers rarely offered strategy suggestions showed little improvement and performed poorly in the posttest, whereas for students whose teachers were high in strategy suggestions, achievement differences did not play a role for students’ recall scores. The authors conclude that teachers’ strategy instruction has an impact on children’s skill (Moely et al. 1992). Hamman et al. (2000) came to similar results, showing that teachers’ coaching of learning was positively associated with students’ self-reported strategy use. However, while students’ use of certain cognitive strategies was found to significantly predict teachers’ coaching of learning, no association was found between teachers’ observed coaching of learning and students’ self-reported use of metacognitive strategies. Zepeda et al. (2019) came to similar conclusions, comparing teachers’ observed instruction of metacognitive strategies in 20 high-conceptual growth classes with that in 19 low-conceptual growth classes. As expected, they found that the support of metacognitive strategies within teacher talk differed between high- and low-conceptual growth classes in the way that high-conceptual growth classrooms had more support of using metacognitive strategies regarding monitoring and evaluation strategies than low-conceptual growth classrooms, except for planning. Although the authors observed significantly more personal metacognitive knowledge statements about one’s abilities and understanding in high-conceptual growth classes, marginally more conditional metacognitive knowledge statements about when and why to apply strategies—were given in low-conceptual growth classes. Finally, no differences in the activation of strategy knowledge were found. Regarding the instructional manner, the results indicated that teachers used more directive talk in the high-conceptual growth classes and marginally more modeling statements in the low-conceptual growth classes. The authors argue that as more metacognitive talk has been found in high-conceptual growth classrooms, this could indicate the positive effect of metacognition on students’ conceptual growth (Zepeda et al. 2019). However, as in the study by Hamman et al. (2000), no causal conclusions can be drawn as teachers might also adapt their strategy instruction to what teachers think their students’ needs are. In their re-analyses of the TIMSS data, Kistner et al. (2010) tested the relationship between teachers’ observed direct and indirect promotion of SRL and students’ achievement gains for the observed teaching unit. They found a significant correlation of students’ learning gains with teachers’ explicit strategy instruction, but not with their implicit strategy instruction. Moreover, their findings suggested that students’ learning gains were substantially associated with constructivist elements of a student-centered learning environment, as well as elements that foster situated learning and transfer, but not with the use of self-directed, independent learning or cooperative settings (Kistner et al. 2010). While this correlational data does not allow to draw causal conclusions, the results indicate that teachers’ different efforts to support students’ SRL may not be equally beneficial to students’ learning gains. Contrary to Kistner et al. (2010), Dignath-van Ewijk et al. (2013) did not find teachers’ observed SRL practice to predict students’ achievement. However, teachers’ observed direct instruction of metacognitive strategies turned out to predict students’ self-reported SRL, while teachers’ observed indirect activation of SRL negatively predicted students’ self-reported SRL. In a similar vein, Depaepe et al. (2010) did not find any differences in learning gains between the two observed classrooms that differed in teachers’ intensity of activation of metacognition. Their results showed that students in both classrooms made significant progress in mathematics over the 7-month-long period, but they differed in their use of the metacognitive strategies, indicating that students applied metacognitive strategies more frequently when the teacher regularly stressed what, how, and why to apply a strategy (Depaepe et al. 2010). Drawing on the findings by Perry and colleagues (1998; Perry and VandeKamp 2000), Lau (2012) applied Perry’s (1998) observation scheme to examine teachers’ SRL practice in secondary school language classrooms in Hong Kong. The analyses of six tenth-grade classrooms suggested that the teachers’ direct instructional support was strongly associated with their students’ use of self-regulation strategies, as well as with their students’ learning motivation, while teachers’ indirect activation of SRL, measured as the degree of autonomy, was negatively associated with their students’ reading performances (Lau 2012). Driven by bringing together different instructional elements that foster SRL, Pauli et al. (2007) re-analyzed the mathematics classrooms of 79 secondary school teachers from the Swiss TIMSS video study (Hiebert et al. 2003) with regard to classroom elements that provide students with independent learning opportunities on the one hand, and classroom elements that foster conceptual understanding and cognitive activation on the other hand. Against their assumptions, Pauli and colleagues (2007) did not discover any effects of neither independent learning opportunities, nor cognitive activation on the development of students’ achievement and interest over the course of the school year. However, they found both instructional elements to be independent of one another, since an increased use of independent learning opportunities did not emerge at the costs of learning opportunities that fostered cognitive activation and conceptual understanding (Pauli et al. 2007).

Which Teacher Characteristics Predict Teachers’ SRL Practice?

Beyond the association between teachers’ SRL practice and student outcomes, some studies investigated how specific teacher characteristics are related to their SRL practice by gathering additional self-report data from teachers that can provide insights into teachers’ beliefs and concepts about SRL and its promotion. In order to accomplish the information gained from their classroom observations, Depaepe et al. (2010) conducted supplementary teacher interviews, which revealed that teachers’ beliefs about the usefulness of a systematic approach affected their strategy instruction positively. Accordingly, teachers’ rating the degree of their reference to the metacognitive model in their teaching reflected the results of the classroom observations: the teacher, who rarely addressed metacognition during his teaching, rated his reference to the model as low, while the other teacher, who received high scores in the classroom observations, rated her reference to the model as high (Depaepe et al. 2010). To the same end, Kistner et al. (2015) investigated associations between the teachers’ instruction of metacognitive strategies, as observed in the TIMSS sample published in an earlier paper (Kistner et al. 2010), and their constructivist beliefs, showing that teachers with more constructivist beliefs addressed more metacognitive planning strategies during their lessons. No associations between teachers’ beliefs and any other type of strategy instruction were identified (Kistner et al. 2015). Also re-analyzing TIMSS data, Pauli and colleagues (2007) investigated whether teachers’ constructivist beliefs are associated with their provision of opportunities for independent problem-solving and of opportunities for SRL. However, they only performed correlation analyses between teacher beliefs and teachers’ self-reported promotion of SRL, but not with the observation data. As both perspectives on teachers’ indirect promotion of SRL were significantly associated, this is a proxy for the observed SRL practice. They found a significant association for teachers’ constructivist beliefs with teachers’ provision of opportunities for independent problem-solving but not with teachers’ provision of opportunities for SRL (Pauli et al. 2007). Spruce and Bol (2015) aimed to link teachers’ beliefs and knowledge about SRL to their SRL practices in the classroom by combining teacher observations with teacher interviews. As their findings revealed, teacher knowledge, beliefs, and SRL practice were not consistently aligned. Although the ten observed teachers held positive beliefs about SRL, their knowledge of SRL and their promotion of SRL in the classroom were generally low. Most teachers had only a vague idea about SRL as related to monitoring activities, but hardly addressed any planning or evaluation in their explanation of SRL. This was also reflected in their observed SRL practice (Spruce and Bol 2015). Similarly, Dignath and Büttner (2018) did not find teachers’ beliefs about SRL to be associated with teachers’ observed or self-reported promotion of SRL. Most teachers reported very positive views about SRL, in particular for the instruction of cognitive and of motivation strategies. However, many teachers struggled with an explanation of metacognitive strategies. Although many teachers reported finding the promotion of SRL important, they rated their own strategy instruction rather low, in particular for metacognitive strategies, which was also reflected in their limited strategy instruction in the observed lessons (Dignath and Büttner 2018).

Discussion

To sum up, the results indicated that teachers focused mainly on the instruction of cognitive strategies, and hardly addressed metacognitive strategies—the most important strategy type to regulate one’s learning (Corno 2008) in the classroom. Among the instruction of metacognitive strategies, hardly any strategies from the planning phase were addressed (Depaepe et al. 2010; Spruce and Bol 2015; Zepeda et al. 2019). This goes in line with the fact that hardly any explicit instruction of strategies took place (see Dignath-van Ewijk et al. 2013, Dignath and Büttner 2018; Bolhuis and Voeten 2001; Depaepe et al. 2010; Kistner et al. 2010, 2015; Spruce and Bol 2015). Thus, most teachers in these studies have allocated only a small amount of teaching time to the explicit instruction of metacognitive strategies. Whereas meta-analyses have shown that training self-regulation strategies gets particularly effective when providing learners with conditional metacognitive knowledge about how, when, and why to apply a certain strategy, most of the studies included in this review have indicated that teachers rarely discuss this with their students; and this results was consistent across primary and secondary school classrooms (Veenman et al. 2009, 2013, Dignath and Büttner 2018; Depaepe et al. 2010; Hamman et al. 2000; Kistner et al. 2010; Michalsky and Schechter 2013; Moely et al. 1992; Zepeda et al. 2019).

Besides, research on instructional teaching elements for SRL has indicated that there are specific instructional elements, which are conducive to SRL, but not every instructional element that supports students’ autonomy is necessarily activating SRL (Perry et al. 2002). Comparable to the results of observation research on strategy instruction, teachers’ SRL practice that explicitly addressed students’ strategies represented less than 10% of the teaching time (Bolhuis and Voeten 2001). Moreover—although there are elements that distinguish classrooms of highly self-regulating students from others—no empirical associations between these elements and students’ achievement outcomes have been demonstrated yet (Pauli et al. 2007). Contrary to the observation studies that focused on direct strategy instruction, these studies were all based on high-inferent coding to rate the learning environment during or after observation.

When looking at classroom characteristics that could be responsible for the variation in teachers’ SRL practice, neither the overall comparison of the studies presented in this review nor the single studies that investigated differences in teachers’ SRL practice between different subjects or grades (e.g., Moely et al. 1992; Hamman et al. 2000) suggest that teachers’ promotion of SRL differs as a function of the school subject or the school grade. However, most studies that delivered data on this indicated that teachers’ promotion of SRL was associated with students’ achievement. This could either mean that teachers’ promotion of SRL affects students’ learning, or that teachers take their instructional decisions with regard to SRL in adaptation to their students’ learning and achievement, but independently of students’ age.

Beyond the description of teachers’ strategy instruction, the results suggest that, on the one hand, teachers’ strategy instruction is associated partly with teachers’ beliefs about learning (Depaepe et al. 2010; Kistner et al. 2015; Spruce and Bol 2015; c.f., Dignath-van Ewijk et al. 2013, Dignath and Büttner 2018), and, on the other hand, with positive learning outcomes of the students (Hamman et al. 2000; Zepeda et al. 2019). However, more specifically, some studies revealed positive associations with student outcomes only for teachers’ explicit strategy instruction (Kistner et al. 2010). Moreover, certain instructional elements, which had been found to be effective for high-quality teaching in general—such as cognitive activation—had been found to be associated with positive student achievement in earlier studies (e.g., Kunter et al. 2013), but in the studies incorporated in this review, this result could not be replicated for all the instructional elements that teachers used to activate SRL, such as cooperative or self-directed learning.

In order to overcome the validity challenges of teachers’ self-report, this review was restricted to studies that assessed teachers’ promotion of SRL by means of classroom observation. While this can be considered as a strength to this review study, at the same time this criterion has reduced the amount of studies that were eligible. Consequently, this review is based on a rather small amount of studies, and so the generalizability of the results is limited. More classroom observation in different educational contexts is needed in order to provide a valid overview of studies on teachers’ SRL practice, which allows for general conclusions. Second, the studies from this review are all based on single moments of assessment and thus offer only correlational data. Longitudinal studies, in particular quasi-experimental or experimental studies, are needed in order to test a causal relationship between teachers’ SRL practice and students’ learning outcomes.

General Discussion

Summary and Implications