Abstract

This paper evaluates the effectiveness of short-time work (STW) schemes for preserving jobs and reducing the segmentation between stable and unstable jobs observed in dual labour markets. For this purpose, we develop and simulate an equilibrium search and matching model considering the situation of the Spanish 2012 labour market reform as a benchmark. Our steady-state results show that the availability of STW schemes does not necessarily reduce unemployment and job destruction. The effectiveness of this measure depends on the degree of subsidization of payroll taxes it may entail: with a 33 % subsidy, we find that STW is quite beneficial for the Spanish economy because it reduces both unemployment and labour market segmentation. We also perform a cost-benefit analysis that shows that there is scope for Pareto improvements when STW is subsidized. Again, the STW scenario with a 33 % subsidy on payroll taxes seems the most beneficial because more than 57 % of workers improve. These workers also experience a significant increase in annual income that could be used to compensate the losers from this policy change and the State for the fiscal balance deterioration. This reform saves the highest number of jobs and has the lowest deadweight costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In fact, the gap between the severance payments of workers with PCs (45 days of wages per year of seniority (p.y.o.s.) for unfair dismissal) and temporary workers (8 days of wages p.y.o.s.) accounts for almost 61 % of total job destruction over the 2008-2012 period, when temporary contracts (TCs) were used as the basic adjustment mechanism (see Bentolila et al. 2012).

External flexibility also increased in 2012 through a reduction in the severance cost gap for unfair dismissals, from 37 to 21 days of wages p.y.o.s. The indemnity of workers with PCs decreased from 45 to 33 days of wages p.y.o.s. and became closer to the mean OECD compensation, which is 21 days of wages p.y.o.s (see OECD 2013), whereas the indemnity of workers with TCs increased from 8 to 12 days of wages p.y.o.s.

Other flexibility measures introduced by these reforms involved the possibility of unilaterally modifying working conditions, such as hours worked and wages for economic, technical or productivity reasons, and redistributing \(10\,\%\) of weekly hours on a yearly basis.

First, priority has been given to firms’ own collective agreements; second, opt-out clauses have been introduced for firms experiencing economic difficulties; and third, the automatic extension of collective agreements once they expire has been reduced to one year.

Lazear (1990) notes that if contracts were perfect, severance payments would be neutral. If the government forced employers to make payments to workers in the case of dismissal, perfect contracts would undo those transfers by specifying opposite payments from workers to employers. Thus, for severance pay to have an effect, some form of incompleteness is needed. Most studies have avoided this problem by modelling dismissal costs as firing taxes; thus, the effects cannot be undone by private arrangements.

According to the European Labour Force Survey, the share of temporary workers over total employment in the last decade was 32.1 % in Spain, whereas it was only 14.4 % in the European Union.

Downward wage rigidity is modelled here as a lower bound on the outcome of the wage negotiations. We need to impose a wage floor to prevent too much internalisation of severance payments.

Part-time wages are adjusted accordingly, that is, they are reduced in the same proportion as hours worked.

Cole and Rogerson (1999) show that an equilibrium always exists when wages do not depend on the unemployment rate but only on the idiosyncratic shock. The intuition is that, given free entry, vacancies adjust to the number of unemployed, and the relevant variable becomes the ratio of unemployed workers to vacancies.

See García-Pérez and Osuna (2014) for a discussion on the robustness of this choice.

In the 2004–2011 period, the monthly average unemployment benefits and coverages are, respectively, 758 euros and 31 %. The sources of these data are the Bulletin of Labour Statistics edited by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, the Spanish Labour Force Survey, and the National Employment Office.

Procedural wages are those wages associated with the interim period between a workers dismissal, contested in court, and the judges decision declaring it unfair.

The distribution of dismissals is taken from the Bulletin of Labour Statistics.

The number of days actually agreed upon is not made public, but this number is presumed to be very close to the legal limit. In contrast, the 2002 reform (Law 45/2002) abolished the firm’s obligation to pay procedural wages when dismissed workers appeal to labour courts as long as the firm acknowledges the dismissal as unfair and deposits the corresponding severance pay within two days of the dismissal.

To obtain the equation displayed in the text, one needs to rearrange terms in the following expression: \(s^{pc}=7\,\% \left[ 45\frac{w}{365}(d-1)+ 60\frac{w}{365}\right] + 20.9\,\%\left[ 45\frac{w}{365}(d-1) + 60\frac{w}{365}\right] + 57.6\,\%\left[ 45\frac{w}{365}(d-1)\right] + 14.5\,\% \left[ 74.3\,\% (45\frac{w}{365}(d-1) +60\frac{w}{365}) + 25.7\,\% (20\frac{w}{365}(d-1)\right] \), which takes into account all the information provided above.

Based on the fact that most firings in the past reached an amount very close to the legal limit, we have set 33 days of wages p.y.o.s, for every firing regardless of whether the dismissal is fair or unfair.

For a robustness exercise concerning parameter values the interested reader can look at the FEDEA Working Paper (http://documentos.fedea.net/pubs/eee/eee2015-06).

For comparability with the data, which include only workers affiliated with social security, we have computed the unemployment rate by excluding from the employment series public servants who do not contribute to social security (those affiliated with MUFACE, the special regime for public servants).

This underestimation may be because, in reality, some low productivity matches may be destroyed immediately once their productivity is realised and not after one year, as assumed in our model.

These effects are probably an upper bound because the model does not allow for changes in bargaining power once the policy is implemented.

References

Abowd, J. M., & Lemieux, T. (1993). The effects of product market competition on collective bargaining agreements: The case of foreign competition in Canada. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(4), 983–1014.

Abraham, K., & Houseman, S. (1994). Does employment protection inhibit labor market flexibility? Lessons from Germany, France, and Belgium. In R. Blank (Ed.), Social protection versus economic flexibility: Is there a trade-off? (pp. 59–94). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Albert, C., García-Serrano, C., & Hernanz, V. (2005). Firm-provided training and temporary contracts. Spanish Economic Review, 7(1), 67–88.

Arpaia, A., Curci, N., Meyermans, E., Peschner, J., & Pierini, F. (2010). Short time working arrangements as response to cyclical fluctuations. European Economy Occasional Papers, No. 64, Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

Bellmann, L., & Gerner, H. D. (2011). Reversed roles? Wage and employment effects of the current crisis. Research in Labor Economics, 32, 181206.

Bentolila, S., Cahuc, P., Dolado, J. J., & Le Barbanchon, T. (2012). Two-tier labour markets in the great recession: France versus Spain. Economic Journal, 122, F155F187.

Boeri, T., & Bruecker, H. (2011). Short-time work benefits revisited: Some lessons from the great recession. Economic Policy, 26(66), 697–766.

Brenke, K., Rinne, U., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2012). Desempleo parcial, la respuesta alemana a la Gran Recesin. Revista Internacional del Trabajo, 132–2, 325–344.

Burdett, K., & Wright, R. (1989). Unemployment insurance and short-time compensation: The effects on layoffs, hours per worker, and wages. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1479–1496.

Cahuc, P., & Carcillo, S. (2011). Is short-time work a good method to keep unemployment down? Nordic Economic Policy Review, 1(1), 133–165.

Calavrezo, O., Duhautois, R., & Walkowiak, E. (2010). Short-time compensation and establishment exit: An empirical analysis with French data, IZA Discussion Paper No. 4989.

Caliendo, M., & Hogenacker, J. (2012). The German labor market after the Great Recession: successful reforms and future challenges, IZA Journal of European Labor Studies, 1:3, pp. 1–24, http://www.izajoels.com/content/1/1/3

Cole, H., & Rogerson, R. (1999). Can the Mortensen-Pissarides matching model match the business-cycle facts? International Economic Review, 40, 933–959.

Contesi, S., & Li, L. (2013). Translating Kurzarbeit. Louis, Economic Synopses No: Federal Reserve Bank of St. 17.

Costain, Jimeno, J. F., & Thomas, C. (2010). Employment fluctuations in a dual labour market, Documento de trabajo 1013, Banco de España.

Dolado, J. J., Ortigueira, S., & Stucchi, R. (2012). Do temporary contracts affect TFP? Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 8763.

Eichhorst, W., & Marx, P. (2009). Reforming German labor market institutions: A dual path to flexibility, IZA Discussion Paper No. 4100.

FitzRoy, F., & Hart, R. (1985). Hours, layoffs and unemployment insurance funding: Theory and practice in an international perspective. Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, 95(379), 700–713.

García-Pérez, J. I., & Osuna, V. (2011). The effects of introducing a single open-ended contract in the Spanish labour market, UPO Working Paper Series, WP 11-07.

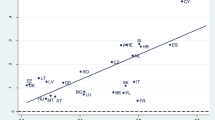

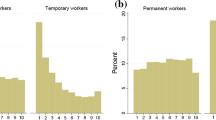

García-Pérez, J. I., & Osuna, V. (2014). Dual labour markets and the tenure distribution: Reducing severance pay or introducing a single contract. Labour Economics, 29, 1–13.

Güell, M., & Petrongolo, B. (2007). How binding are legal limits? Transitions from temporary to permanent work in Spain. Labour Economics, 14–2, 153–183.

Hijzen, A., & Martin, S. (2012). The role of short-time working schemes during the global financial crisis and early recovery: A cross-country analysis, OECD Social, employment and migration working papers, No. 144, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k8x7gvx7247-en

Hijzen, A., & Venn, D. (2011). The role of short-time work schemes during the 2008–2009 recession, OECD social, employment and migration working papers, No. 115, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kgkd0bbwvxp-en

Lacuesta, A., Puente, S., & Villanueva, E. (2012). The schooling response to a sustained increase in low-skill wages: Evidence from Spain 1989–2009, Bank of Spain Working Paper No. 1208.

Lazear, E. (1990). Job security provisions and employment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105, 699–726.

Möller, J. (2010). The German labor market response in the world recession: De-mystifying a miracle. Journal for Labor Market Research, 42, 325336.

Mortensen, D., & Pissarides, C. (1994). Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. Review of Economic Studies, 61, 397–415.

OECD. (2013). The 2012 labour market reform in Spain: A preliminary assessment, http://www.oecd.org/els/emp/SpainLabourMarketReform-Report

OECD. (2014). OECD economic surveys: Spain 2014. OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/eco_surveys-esp-2014-en.

Osuna, V. (2005). The effects of reducing firing costs in Spain. In Contributions to macroeconomics (Vol. 5(1), pp. 1–29). The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, Berkeley Electronic Press.

Rinne, U., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2012). Another economic miracle? The German labor market and the great recession, IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 1:3, pp. 1-21, http://www.izajoelp.com/content/1/1/3

Rosen, S. (1985). Implicit contract: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 23, 1144–1175.

Scholz, T. (2012). Employers selection behavior during short-time work, IAB Discussion Paper No. 18/2012.

Tauchen, (1986). Statistical properties of generalized method-of-moments estimators of structural parameters obtained from financial market data. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, American Statistical Association, 4(4), 397–416.

Vroman, W., & Brusentsev, V. (2009). Short-time compensation as a policy to stabilise, Department of Economics, University of Delaware Working Paper, Vol. 2009-10.

Walsh, S., London, R., McCanne, D., Needels, K., Nicholson, W., & Kerachsky, S. (2007). Evaluation of short-time compensation programs, Berkeley Planning Associates / Mathematica Policy Research Inc., Final Report for the U.S. Department of Labor, March 2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We gratefully acknowledge the support from research projects PAI-SEJ513, PAI-SEJ479, P09-SEJ4546, ECO2012-35430, P09-SEJ688 and ECO2013-43526-R. The usual disclaimer applies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osuna, V., García-Pérez, J.I. On the Effectiveness of Short-time Work Schemes in Dual Labor Markets. De Economist 163, 323–351 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-015-9256-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-015-9256-x

Keywords

- Permanent and temporary contracts

- Duality

- Severance costs

- Short-time work

- Unemployment

- Tenure distribution

- Job destruction