Abstract

The Indian economy is currently passing through a critical phase of economic development as its structural transformation in employment has stalled, whilst both the youth unemployment rate and the number of youths “Not in Employment, Education, and Training (NEET)” have increased to an unprecedentedly high level. In the context in which the share of the youth population is continuing to rise despite the declining fertility rate to below the replacement rate, increased educated youth unemployment has caused an upsurge in the Discouraged Labour Force (DLF). This paper explores the trends, composition, and determinants of rising DLF in India using national level employment-unemployment surveys and macro-level panel data. Based on Multinomial logit and System GMM regression results, it is argued that policies aiming to enhance human capabilities through an improved base of technical education and the promotion of industry are necessary to enhance the growth of quality jobs in order to combat the problem of rising educated youth unemployment and DLF. Moreover, these measures could help in the process of harnessing the demographic dividend in India through an increased level of labour productivity in the long run.

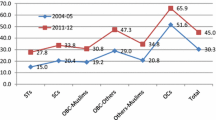

Source: Authors’ calculation and plot using NSS (EUS and PLFS) data

Source: Authors’ calculation and plot using NSS unit level data

Source: Authors’ calculation and plot using NSS and PLFS unit level data

Source: Authors’ calculation and plot using the micro-level regression post estimation results

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This advantage is likely to be over by 2040 and the Indian economy will become an ageing society forever.

As per the National Youth Policy (2014), Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Government of India, the youth population consists of persons belonging to the age group 15 to 29 years.

Although the youth completed education and training but were neither found in jobs nor searched for jobs (actively or passively), this could be partly called the DLF. We classified them as out of labour force. Persons belonging to this category were excluded from our sample to avoid confusion.

These workers consist of women and young male members of the family. They are not the principal breadwinners of the family, but they support and supplement the family income during times of crisis.

Population projection done by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India. Report of the technical group on population projections, November, 2019.

References

Abraham AY, Ohemeng FNA, Ohemeng W (2017) Female labour force participation: evidence from Ghana. Int J Soc Econ 44(11):1489–1505. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-06-2015-0159

Agbola FW (2005) Integrating hidden unemployment in the measurement of unemployment in selected OECD countries. Appl Econ Int Dev 5(2):91–108

Akankwasa K, Ortmann GF, Wale E, Tushemereirwe WK (2013) Farmers’ choice among recently developed hybrid banana varieties in Uganda: a multinomial logit analysis. Agrekon 52(2):25–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2013.798063

Akinyemi BE, Mushunje A (2017) Born free but “NEET”: determinants of rural youth’s participation in agricultural activities in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Int J Appl Bus Econ Res 15(19):521–533

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J Econom 68(1):29–51

Bairagya I (2018) Why is unemployment higher among the educated? Econ Polit Wkly 53(7):43–51

Bălan M (2015) Methods to estimate the structure and size of the “neet” youth. Proc Econ Financ 32:119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01372-6

Batini F, Corallino V, Toti G, Bartolucci M (2017) NEET: a phenomenom yet to be explored. Interchange 48(1):19–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-016-9290-x

Becker GS (1975) Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Columbia University Press, Columbia

Becker GS (1985) Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. J Labor Econ 3(1):33–58

Benati L (2001) Some empirical evidence on the ‘discouraged worker’effect. Econ Lett 70(3):387–395

Bendewald J (2008) Subsistence theory in the US context: a cross‐sectional labor supply estimate, honors projects. In: Paper 7. Economics Department, Macalester College, St. Paul, MN. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/economics_honors_projects/7

Bhattacharyya SS, Nair S (2019) Explicating the future of work: perspectives from India. J Manag Dev 38(3):175–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2019-0032

Bjørnstad R (2006) Learned helplessness, discouraged workers, and multiple unemployment equilibria. J Soc Econ 35(3):458–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.030

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143

Blundell R, Ham J, Meghir C (1998) Unemployment, discouraged workers and female labour supply. Res Econ 52(2):103–131

Carcillo S, Königs S (2015) NEET youth in the aftermath of the crisis: challenges and policies. OECD social, employment and migration working papers, No. 164, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5js6363503f6-en

Caroleo FE, Rocca A, Mazzocchi P, Quintano C (2020) Being NEET in Europe before and after the economic crisis: an analysis of the micro and macro determinants. Soc Indic Res 149:991–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02270-6

Chaudhary R, Verick S (2014) Female labour force participation in India and beyond. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/lang--en/index.htm

Chauhan RK, Mohanty SK, Subramanian SV, Parida JK, Padhi B (2016) Regional estimates of poverty and inequality in India, 1993–2012. Soc Indic Res 127(3):1249–1296

Congregado E, Gałecka-Burdziak E, Golpe AA, Pater R (2021) Separating aggregate discouraged and added worker effects: the case of a former transition country. Oecon Copernic 12(3):729–760

Cuaresma CJ, Lutz W, Sanderson W (2014) Is the demographic dividend an education dividend? Demography 51(1):299–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0245-x

Dernburg T, Strand K (1966) Hidden unemployment 1953–62: a quantitative analysis by age and sex. Am Econ Rev 56(1/2):71–95

Deshpande A (2020) Early effects of lockdown in India: Gender gaps in job losses and domestic work. Indian J Labour Econ 63:87–90

Deshpande A, Kabeer N (2021) Norms that matter: exploring the distribution of women's work between income generation, expenditure-saving, and unpaid domestic responsibilities in India (no. 2021/130). WIDER Working Paper

Dessing M (2008) The S-shaped labor supply schedule: evidence from industrialized countries. J Econ Stud 35(6):444–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443580810916505

Ehrenberg RG, Smith RS (1988) Modem labor economics: theory and public policy. Scott, Foresman, Glenview

European Union Committee (2014) Youth unemployment in the EU: a scarred generation? House of Lords, Great Britain

Evans A (2018) Evidence of the added-worker and discouraged-worker effects in Australia. Int Rev Appl Econ 32(4):472–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2017.1351530

Filatriau O, Reynès F (2012) A new estimate of discouraged and additional worker effects on labor participation by sex and age in OECD countries. OFCE Document de Travail, Paris, p 9

Fuchs J, Weber E (2017) Long-term unemployment and labour force participation: a decomposition of unemployment to test for the discouragement and added worker hypotheses. Appl Econ 49(60):5971–5982. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1368991

Fujita S, Ramey G (2009) The cyclicality of separation and job finding rates. Int Econ Rev 50(2):415–430

Goldin C (1994) The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history.In: NBER working paper no. 4707, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Gong X (2010) The added worker effect and the discouraged worker effect for married women in Australia. In: IZA discussion papers, no. 4816, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn

Hirway I (2012) Missing labour force: an explanation. Econ Polit Wkly 47(37):67–72

Jones EB, Long JE (1979) Human capital and labor market employment: additional evidence for women. J Hum Resour 14(2):270–279

Kannan KP, Raveendran G (2012) Counting and profiling the missing labour force. Econ Polit Wkly 47(6):77–80

Kingdon GG, Unni J (2001) Education and women's labour market outcomes in India. Educ Econ 9(2):173–195

Kollmann R (1994) Hidden unemployment a search-theoretic interpretation. Econ Lett 46(4):351–355

Kotschy R, Urtaza PS, Sunde U (2020) The demographic dividend is more than an education dividend. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117(42):25982–25984. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012286117

Kuch PJ, Sharir S (1978) Added-and discouraged-worker effects in Canada, 1953–74. Can J Econ 11(1):112–120

Laborda L, Sotelsek D (2019) Effects of road infrastructure on employment, productivity and growth: an empirical analysis at country level. J Infrastruct Dev 11(1–2):81–120

Lee GH, Parasnis J (2014) Discouraged workers in developed countries and added workers in developing countries? Unemployment rate and labour force participation. Econ Model 41:90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.04.005

Lundberg S (1985) The added worker effect. J Labor Econ 3(1):11–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/298069

Madheswaran S, Parida JK (2021) Declining labour-force participation in India: does education and training help? India higher education report 2020. Routledge, India, pp 68–88

Maloney T (1991) Unobserved variables and the elusive added worker effect. Economica 58(230):173–187. https://doi.org/10.2307/2554650

Mascherini M, Salvatore L, Meierkord A, Jungblut JM (2012) NEETs-Young people not in employment, education or training: characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe

Mason A (2003) Capitalizing on the demographic dividend. Population and poverty: achieving equity, equality and sustainability, chapter 2. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), New York, pp 39–48

Mehrotra S (2015) Realising the demographic dividend: policies to achieve inclusive growth in India. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mehrotra S, Parida JK (2017) Why is the labour force participation of women declining in India? World Dev 98:360–380

Mehrotra S, Parida JK (2019) India’s employment crisis: rising education levels and falling non-agricultural job growth. In: CSE working paper no. 2019–04. Azim Premji University, Bangalore

Mehrotra S, Parida JK (2021a) Stalled structural change brings an employment crisis in India. Indian J Labour Econ 64:281–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-021-00317-x

Mehrotra S, Parida JK (2021b) Why human development should precede economic growth in the states. Econ Polit Wkly 56(38):54–61

Mehrotra S, Parida J, Sinha S, Gandhi A (2014) Explaining employment trends in the Indian economy: 1993–94 to 2011–12. Econ Polit Wkly 49(32):49–57

Mian AR, Sufi A (2012) What explains high unemployment? The aggregate demand channel (no. w17830). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Mihail DM, Karaliopoulou K (2005) Greek university students: a discouraged workforce. Educ Train 47(1):31–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910510580610

Mitra A, Singh J (2019) Rising unemployment in India: a statewise analysis from 1993–94 to 2017–18. Econ Polit Wkly 54(50):12–16

Mitra A, Verick S (2013) Youth employment and unemployment: an Indian perspective. In: ILO Asia-Pacific working paper series, International Labour Organization, Geneva. Retrieved 3 March 2014

Nardi B, Arimatea E, Giunto P, Lucarelli C, Nocella S, Bellantuono C (2013) Not employed in education or training (NEET) adolescents with unlawful behaviour: an observational study. J Psychopathol 19:42–48

Parola A, Felaco C (2020) A narrative investigation into the meaning and experience of career destabilization in Italian NEET. Mediterr J Clin Psychol 8(2):1–22. https://doi.org/10.6092/2282-1619/mjcp-2421

Pervaiz H, Saleem MZ, Sajjad M (2012) Relationship of unemployment with social unrest and psychological distress: an empirical study for juveniles. Afr J Bus Manag 6(7):2557–2564

Ponomareva N, Sheen J (2010) Cyclical flows in Australian labour markets. Econ Rec 86:35–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2010.00658.x

Prieto-Rodríguez J, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez C (2000) The added worker effect in the Spanish case. Appl Econ 32(15):1917–1925

Rangarajan C, Kaul PI, Seema (2011) Where is the missing labour force? Econ Polit Wkly 46(39):68–72

Richards TJ (2020) Income targeting and farm labor supply. Am J Agric Econ 102(2):419–438

Roodman D (2009) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. Stata J 9(1):86–136

Savitha B, Kumar KN (2016) Non-performance of financial contracts in agricultural lending: a case study from Karnataka India. Agric Financ Rev 76(3):362–377. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-01-2016-0001

Sedai AK, Vasudevan R, Pena AA, Miller R (2021) Does reliable electrification reduce gender differences? Evidence from India. J Econ Behav Organ 185:580–601

Singh S, Parida JK (2020) Employment and earning differentials among vocationally trained youth: evidence from field studies in Punjab and Haryana in India. Millenn Asia 13(1):142–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976399620964308

Tamesberger D, Bacher J (2014) NEET youth in Austria: a typology including socio-demography, labour market behaviour and permanence. J Youth Stud 17(9):1239–1259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.901492

Tano DK (1993) The added worker effect: a causality test. Econ Lett 43(1):111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(93)90142-Y

Tansel A, Ozdemir ZA (2018) Unemployment invariance hypothesis, added and discouraged worker effects in Canada. Int J Manpow 39(7):929–936. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-04-2017-0059

Theeuwes J (1981) Family labour force participation: multinomial logit estimates. Appl Econ 13(4):481–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036848100000014

Van Ham M, Mulder CH, Hooimeijer P (2001) Local underemployment and the discouraged worker effect. Urban Stud 38(10):1733–1751

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have not received any funds for conducting this research. Hence, we declare that we do not have any conflict of interest with any individual or organisation with respect to this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Parida, J.K., Pattayat, S.S. & Verick, S. Why is the size of discouraged labour force increasing in India?. Econ Change Restruct 56, 3601–3630 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-023-09538-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-023-09538-0