Abstract

Free-riding is often associated with self-interested behaviour. However, if there is a global pollutant, free-riding will arise if individuals calculate that their emissions are negligible relative to the total, so total emissions and hence any damage that they and others suffer will be unaffected by whatever consumption choice they make. In this context consumer behaviour and the optimal environmental tax are independent of the degree of altruism. For behaviour to change, individuals need to make their decisions in a different way. We propose a new theory of moral behaviour whereby individuals recognise that they will be worse off by not acting in their own self-interest, and balance this cost off against the hypothetical moral value of adopting a Kantian form of behaviour, that is by calculating the consequences of their action by asking what would happen if everyone else acted in the same way as they did. We show that: (a) if individuals behave this way, then altruism matters and the greater the degree of altruism the more individuals cut back their consumption of a ‘dirty’ good; (b) nevertheless the optimal environmental tax is exactly the same as that emerging from classical analysis where individuals act in self-interested fashion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In a recent paper assessing the challenges that policy-makers and society face in addressing climate change, Galarraga and Markandya (2009) point out the key ethical and welfare considerations that need to be taken into account – in particular the intra-and inter-generational impact of the damage that climate change may bring.

While economists frequently consider these ethical considerations in terms of the formulation of the appropriate welfare objective for policy-makers to pursue, an equally important issue is how far individuals themselves take these factors into account when deciding what actions to take and what policies they are willing to support. This raises the important question of the extent to which policy action might be needed if individuals themselves are willing to alter their behaviour as they recognise the potential harm that their actions might cause.

As both Stern (2007) and Galarraga and Markandya (2009) point out, climate change represents one of the largest externalities that society has had to face, and, like all externalities, the fundamental need for policy intervention arises from free-riding behaviour—in this case not just by individuals and companies but also by governments.

In the classical analysis of externalities, free-riding arises because individuals are purely self-interested, and so perceive that, while they bear all the costs of changing their consumption behaviour, they may get only a very small gain in terms of the reduced damage that they themselves will suffer. In the extreme case, individuals may calculate that their emissions are so insignificant relative to the total, that total emissions and hence any damage that they (and others) might suffer will be unaffected by whatever consumption choices they make.Footnote 1 In these circumstances individuals make their consumption choices ignoring any effect these choices have on climate change and the damage it will cause.Footnote 2 The classic prescription is the introduction of a Pigovian tax (equal to social marginal damage) so that individuals face the full economic cost of their consumption decisions.

It is sometimes thought that if individuals are not self-interested, but instead are altruistic and so take account of the effect of their actions on others, this may overcome free-riding behaviour. However, as we will show, as long as individuals continue to believe that total emissions are completely unaffected by whatever they do, then however much they care about others, their behaviour will not change, and the optimal policy is to impose exactly the same tax as if individuals were self-interested.

For individual behaviour to change, individuals need to make their consumption decisions in a different way. While there have been a number of theories of pro-social behaviour, these typically involve individuals obtaining some kind of utility gain from behaving morally. In this paper we propose a new theory of moral behaviour whereby individuals recognise that they will be worse off by not acting in their own self-interest, and balance this cost off against a hypothetical moral value of adopting a Kantian form of behaviour, that is by calculating the consequences of their action by asking what would happen if everyone else acted in the same way as they did. We show that

-

(i)

Individuals behaving this way will adjust their behaviour to take account of the impact of their decision on themselves and others.

-

(ii)

If individuals behave in this way, then altruism matters and the greater the degree of altruism the more individuals cut back their consumption of a ‘dirty’ good.

-

(iii)

Nevertheless the optimal environmental tax is exactly the same as that emerging from the classical analysis where individuals are purely self-interested.

A key result of this paper is that the existence of altruistic and ‘moral’ behaviour does not change the socially optimal tax on an environmentally harmful good. Johansson (1997) previously modelled the socially optimal tax on an externality for different types altruism and compared it to the standard Pigovian tax level. Contrary to our results he finds that depending on the type of altruism analysed, the socially optimal tax on the externality can be higher, lower, or equal to the Pigovian tax. However, Johansson (1997) uses a different approach to analysing the case where individual’s behaviour is driven by something other than maximising their utility (Genuine Altruism), and finds that the optimal tax is lower than under standard theory.Footnote 3

The paper will proceed as follows. In Sect. 2 we conduct a brief discussion of the literature on pro-social behaviour and altruism. Section 3 then develops the model, starting with standard theory excluding any form of altruism in Sect. 3.1. This serves as counterfactual to the remaining analysis. We then proceed in Sect. 3.2 to layer on a type of Pure Altruism that will be defined carefully in what follows. Section 3.3 then turns to the central element of this paper by developing the theory of moral behaviour. Finally, Sect. 4 will present a brief discussion of the model and the results.

2 Review of Literature

As described in the introduction, pro-social (and pro-environmental) behaviour is usually at odds with standard economic analysis, which predicts that in a non-cooperative setting, individuals only make negligible contributions to public goods. For example, Andreoni (1988) shows that in large populations the share of individuals making contributions to a public good tends to zero as the free-riding effect dominates.Footnote 4 However, when contributing to the public good also yields some utility benefit to the individual, voluntary contributions can be consistent with standard economic models. Andreoni (1989, 1990) models the individual’s utility not just as a function of the consumption of the private and public goods, but also of the individual’s contribution to the public good itself. This is commonly referred to as the ‘warm-glow’ effect and describes a form of Impure Altruism.Footnote 5 ‘Warm-glow’ can also be interpreted as a self-image gain from contributing to the public good.Footnote 6 While Andreoni makes no assumptions regarding the psychological cause of this ‘warm-glow’, various other authors have developed more sophisticated models with regard to the underlying motivation. These models usually work on the premise that individuals derive intrinsic value from a self-image desire or social norms. Bénabou and Tirole (2006), for example, model a “reputational payoff” (p. 1656) from contribution to a public good, which is also a function of the belief others have regarding the type of consumer this individual is. In a model by Ellingsen and Johannesson (2008) the level of social approval depends on whether the individual himself approves of the person who approves him. Nyborg et al. (2006) also construct a model where individuals are motivated by a concern for self-image. However, this self-image is a function of the total benefit a ‘green’ good yields to the population, as well as their perception of what share of the population is choosing to consume the ‘green’ option.Footnote 7 This means the consumer’s intrinsic incentive to be pro-social increases as the share of the population acting that way increases.Footnote 8 On the other hand, Brekke et al. (2003) develop a model where individuals are able to make a more sophisticated calculation of the “morally ideal effort” (p. 1971). This is achieved by evaluating the socially optimal contribution to a public good if they and everybody else were to make the same choice. The individual then derives self-image value depending on how close their contribution is to that socially optimal level, while trading off the self-image gain against the utility benefit from consumption.Footnote 9

Essentially most of the contributions discussed above capture a form of Impure Altruism where, to some extent, the contribution itself matters to an individual’s utility. However, altruism is instead often viewed as a concern for the welfare of others.Footnote 10 The two main types of altruism that capture an individual’s concern for others’ welfare are Pure Altruism and Paternalistic Altruism. Pure Altruism uses the idea that an individual’s utility may to some degree be a function of others’ utility, but not just a specific component of it. Applications of this type of altruism are often used with smaller settings, such as the family where one might care about the welfare of specific individuals (for example Becker (1974, 1981)). In large-scale contexts it can also be assumed that an individual cares for the total or average welfare of all other individuals in the population (see Hammond 1987; Johansson 1997 for examples).Footnote 11 Paternalistic Altruism differs from Pure Altruism in that it does not assume that an individual’s utility is a function of others’ utility as such, but a specific component of that utility (see Archibald and Donaldson 1976). In an environmental context, this component may be the damage experienced by others from the environmentally harmful good. While Impure Altruism only takes into account the individual’s contribution to the externality, Paternalistic Altruism means that the individual is affected by others’ experience of the externality, regardless of the individual’s contribution. All these types of altruism still assume that individuals maximise their utility when acting pro-socially. Genuine Altruism as defined by Kennett (1980), on the other hand, requires that individuals’ behaviour is driven by some function other than maximising their utility. For example, the individual may make the consumption choice by maximising a function consisting of their own utility and everybody else’s utility, but by doing so will incur a loss in utility compared to standard economic behaviour.Footnote 12 Since this implies a deviation from ‘rational’ behaviour driven by self-interest economists usually assume, it is the most drastic form of altruism.

Johansson (1997) models the socially optimal tax on an externality for all four types of altruism described above and compares it to the standard Pigovian tax level.Footnote 13 He finds that under Pure Altruism the optimal level of tax is equal to the standard Pigovian level in large populations.Footnote 14 However, with a form of Genuine Altruism where individuals maximise a function of the weighted sum of their own utility and everybody else’s utility, Johansson (1997) finds that the optimal tax is lower than the Pigovian tax. The socially optimal level of consumption is unchanged from the standard level as this type of altruism does not affect it, but the individual will demand this lower level of consumption due to the function maximised and therefore the requirement on the tax level is reduced. If the weight in the maximisation were equal between the individual’s utility and all others’ utility, the tax rate would drop to zero.Footnote 15 In his analysis Johansson (1997) recognises that Genuine Altruism is the most controversial of all types of altruism as it contradicts mainstream economic theory. Yet the traditional model has already for a long time drawn fundamental criticism. Sen (1977) describes why the economist prefers to assume the existence of a selfish being: “It is possible to define a person’s interests in such a way that no matter what he does he can be seen to be furthering his own interests in every isolated act of choice.” (p. 322). Indeed it means that every action can be explained simply through the concept of revealed preferences. This saves the economist from having to take a closer look at what constitutes preferences and utility, or as Sen (1977) puts it: “...a robust piece of evasion.” (p. 323). Sugden (1982) further argues that assuming utility-maximising behaviour in the traditional sense may be too constricting and different people might indeed maximise very different functions in order to determine their consumption choice.

The criticism presented here does not seek to suggest that the utility-maximising model is without value, and the critical literature usually acknowledges the usefulness of the traditional model, especially in market-exchange situations. But in the context of this paper it has to be recognised that environmental issues are often subject to strong moral views.Footnote 16 As Frey (1999) summarises, contrary to the utilitarian perspective, a moralist views the environment with unique value and believes that it should be protected purely for ethical reasons and with little or no regard to any trade-offs. Furthermore, Arrow (1986) argues that rationality as the economist defines it often only occurs through market exchange, rather than through the intrinsic motivation of an individual. However, as Shogren and Taylor (2008) point out, environmental resources are frequently not subject to the market exchange required for consistent choices. Furthermore, we put forward that when individuals realise that the government is not able to set the incentives correctly, they may also recognise that the result will be far from optimal for themselves and everybody else without a change in behaviour. This may, in turn, lead to moral motivation that requires a different type of model to explain. Along the lines of Harsanyi (1955), Sen (1977) develops the idea that people may have two preference relations working at the same time.Footnote 17 Utility-maximising behaviour with some consideration for the utility of others he labels as ‘sympathy’, while actions driven only by their moral value with no consideration of utility he calls ‘commitment’.Footnote 18 The latter is very much in line with Kant’s concept of ‘duty’.Footnote 19

Laffont (1975) develops the idea of a Kantian approach to behaviour where individuals consider what would be optimal if they and everybody else were to make the same choice.Footnote 20 However, Laffont (1975) assumes that individuals are identical, with all individuals applying this rule equally. In his model this implies that individuals will correctly anticipate that everybody else will indeed behave the same way, meaning that ultimately individuals still maximise their personal utility. Our approach differs to that of Laffont (1975) in that we model individuals having no expectations regarding the behaviour of others and they assume that all others continue to behave in the utility-maximising way. Individuals therefore recognise that acting morally means they will suffer a loss of personal utility. The central aspect of our approach is that individuals assess the intrinsic ‘moral value’ of their action by comparing the utility they actually get to the utility they would get if everyone else were to make the same choice as this individual.Footnote 21 Individuals then trade of this hypothetical ‘moral value’ of the action against the associated utility cost when making their consumption choice.

In addition to the modelling of ‘moral value’, we also consider that individuals may have altruistic concern for others’ utility (Pure Altruism). In line with Hammond’s (1987) definition, we model that people may exhibit altruistic concern for the utility of all other individuals as a collective. Specifically, our model assumes that an individual’s utility function is the sum of their direct utility from consumption and the total utility of all other individuals weighted by the degree of altruistic concern.Footnote 22 While Johansson (1997) also models this form of Pure Altruism, we differ by explicitly modelling a continuum of individuals in order to capture the atomistic nature of individuals’ consumption choice in the context of large-scale environmental problems such as climate change. Such an individual would recognise the atomistic nature of their choice and hence, when making their consumption decision, takes average and total levels of consumption, welfare as well as damage from the externality as given. It is noteworthy that both the discrete and continuous approaches are widely used in the literature depending on the issue to be addressed. Finally, by modelling a combination of two different types of altruism, ‘Pure Altruism’ (the concern for others’ utility) and ‘Genuine Altruism’ (the propensity to act morally through non-utility-maximising behaviour), we capture the idea that people may be concerned about the welfare of others but may also have some propensity to act morally despite their inability to influence the impact of the environmentally harmful good.

Of course a distinction between Kant’s categorical imperative and our model is that Kant sees moral duties as absolute that completely supersede any considerations of utility. Our model, on the other hand, does not use such a binary approach, but allows the individual’s propensity to act morally to determine in how far they are driven by the moral value of the action relative to the associated loss in utility. Only individuals with full propensity to act morally will completely disregard their own utility and act in a fully Kantian fashion. At the same time, individuals with no propensity to act morally will not take into account the moral value at all and thus act in a standard utility-maximising way. The propensity to act morally is assumed to be an exogenous parameter that is distributed across different types of individuals in the economy. Since we make no assumption regarding what this distribution may look like, we do not argue that people necessarily have a certain propensity to act morally but we simply evaluate the consequences for the socially optimal tax on an environmentally harmful good if some people do act this way.

3 The Model

3.1 Standard Theory

We start with a population consisting of a continuum of potentially different types of individuals. These types are indexed by \(k\in [{0,1}], 0\le k\le 1\). The distribution is given by the density function

Each individual has the same initial endowment of income \(y>0\) and chooses between a ‘clean’ good \(x\) and a ‘dirty’ good \(z\). The clean good is a numeraire good with a price of 1 and therefore represents the expenditure on all other goods but \(z\). Its consumption is assumed to generate no externalities. On the other hand, the dirty good generates one unit of emissions per unit consumed, which is a negative externality to all individuals. Further, let \(\zeta (.)\) denote the function that assigns to an individual of type \(k\) their chosen consumption of the dirty good, \(\zeta (k)\ge 0\), and let \(\bar{z}\) denote the average consumption of the dirty good. The size of the population is measured by \(M>0\) and therefore total emissions \(E\) are

Each individual derives utility from the personal consumption of the two goods. For simplicity we assume that preferences over the two goods are the same across all types and as such all individuals have identical utility functions.Footnote 23 Additionally, utility is assumed to be linear in consumption of the clean good in order to avoid issues of income distribution.Footnote 24 This means as long as consumers always consume a positive amount of the clean good, the marginal utility of income is constant and welfare losses that may arise are not due to inequality but inefficiencies.

Utility derived from the consumption of the two good takes the following form:

The damage from emissions experienced by individuals is captured by the damage function \(D(E)\). It is a strictly increasing and convex function for all positive levels of emissions. Furthermore, \(\phi (z)\) describes the private gross benefit gained from consumption of the dirty good and is strictly increasing and strictly concave in \(z\).

The dirty good is produced by a perfectly competitive industry operating with constant unit costs \(c>0\). At the same time, the government imposes an emissions tax \(t\ge 0\) on the consumption of \(z\). The tax revenue is redistributed to the individuals through a lump-sum transfer \(\sigma \) that is identical for all individuals. Therefore the government budget constraint is defined by

Using the definition of emissions provided in (1) and the government budget constraint, we can now derive the utility from personal consumption and emissions as a function that only depends on the individual’s consumption level of the dirty good, and the average consumption of the dirty good:

In line with the idea of atomistic consumption, in all stages of the analysis we use the standard Nash assumption that the individual always takes the consumption by everyone else as given when making the choice over consumption of the dirty good. This means that the individual treats average emissions as independent of \(z\) because their choice of consumption of the dirty good has no influence on average and total emissions. Indeed, based on the definition of total emissions as shown in (1), even if every other individual of the same type as this one were to change their consumption simultaneously, it would still not impact the level of average or total emissions.

Using this basic setup, the individual chooses \(z\) to maximise their direct personal utility as given by (4). Under standard utility-maximising behaviour the chosen level of consumption of the dirty good can therefore be characterised by

As we would expect, the left hand side of (5) describes the marginal gross benefit of consumption of the dirty good and the right hand side describes the private marginal cost of consumption. Further, as we would expect given the atomistic nature of the consumption choice in this model, the damage incurred from the dirty good is not a factor in determining the chosen consumption level under standard theory.

Given this we can determine that for any tax rate t and any dirty good assignment function \(\zeta (.)\), social utility across all individuals in the population is

Since individuals have identical, and strictly concave utility functions, the socially optimal consumption level requires that everyone consume the same amount of the dirty good. This common level, \(\hat{z}\), is defined as

As we can see, the social planner takes account of the link between the taxes paid on the dirty good and the lump-sum transfer received by consumers through the government budget constraint. This means that the socially optimal level of consumption is independent of the tax rate \(t\). In addition, the social planner also takes into account the connection between the consumption of the dirty good and total emissions. As we would expect, this means that the social planner can fully internalise the externality. The socially optimal level of consumption of the dirty good \(\hat{z}\) is then implicitly defined by

This shows that, from a social planner’s perspective, the social marginal cost of consumption consists of the direct marginal cost of production of the dirty good, as well as the social marginal damage created by the emissions externality, \({\textit{MD}}^{{\prime }}(M\hat{z})\), but not the tax on the dirty good since the revenues are entirely redistributed to the individuals.

From (5) and (8) it is also straightforward to see that the government can achieve the socially optimal consumption level by setting the tax on the dirty good equal to the social marginal damage of consumption (the standard Pigovian tax). Denoting this optimal tax rate by \(\hat{t}\), it follows that

So far we have only described the basic model setup and laid out the results under standard theory. These will serve as a counterfactual for the remaining analysis.

3.2 Pure Altruism

As discussed in the introduction, Pure Altruism in this model means that individuals may put some weight on the total utility of all other individuals in the population. Individuals will therefore not only maximise their own private utility from consumption, but the (weighted) sum of their own private utility and the total utility of all others. For simplicity we will assume that the degree of altruistic concern does not vary across different types of individuals.Footnote 25 The weight given to the total utility of others is denoted \(\alpha \ge 0\) for all \(k\). Then the total welfare of an individual who consumes an amount \(z\) of the dirty good isFootnote 26

Given the atomistic nature of consumption, the total utility of all other individuals in the population is simply equal to the social utility as defined in (6). Furthermore, individuals still treat the consumption of all other individuals as given when making their consumption choice over the dirty good. This means individuals treat the assignment function \(\zeta (k)\), and hence the average consumption level \(\bar{z}\), as well as the level of social utility \(S(.)\), as given. Indeed this means that individuals do not just take as given the damage they themselves suffer from the externality, but also the damage that everyone else suffers.

It follows that, with atomistic consumption, if the individual chooses the level of consumption of the dirty good that maximises total individual welfare, then, independent of the level of altruistic concern, consumption will be the same as the level that maximises their utility as characterised by (5).

Since we assumed a constant level of \(\alpha \) for all types of individuals, we still have identical personal welfare functions for all individuals. Using (10) it is then straightforward to derive that, for any given tax rate \(t\) and assignment function \(\zeta (.)\), the total welfare of all individuals, or social welfare, is given by

This shows that the level of altruistic concern across the population only scales up the total level of welfare, but the socially optimal level of consumption is still one in which everyone consumes the same amount of the dirty good as determined by standard theory. Consequently the level of \(\hat{z}\) is still defined by (8) and the optimal tax inducing everyone to consume the socially optimal level is still described by (9). This result leads us to the first proposition.

Proposition 1

In a world of atomistic consumption, with every individual choosing their consumption by maximising their utility, altruistic concern for the utility of others has no impact on the optimal level of consumption for the individual, the socially optimal level of consumption or the socially optimal tax level.Footnote 27

Proof

By maximising individual welfare as shown in (10), it is straightforward to derive that \(\phi ^{\prime }(z)=c+t\), which is the same as derived without altruism in (5). Similarly, maximising the social welfare function as shown in (11), we derive that \(\phi ^{\prime }(\hat{z})=c+{\textit{MD}}^{\prime }(M\hat{z})\), the same level as under standard theory in (8). Combining these two findings it is also evident that \(\hat{t}={\textit{MD}}^{{\prime }}\left( {M\hat{z}} \right) \) induces everyone to consume the same socially optimal amount, the same as shown under standard theory without altruism.

So far we have established the results with and without altruistic concern for the utility of others based on standard utility-maximising behaviour. We will now turn to the key part of this paper and develop the theory of moral behaviour.

3.3 Moral Behaviour

We start by assuming that initially everyone consumes \(\tilde{z}(t)\), which is the chosen consumption level consistent with standard theory as derived in Sect. 3.1. And since we want to investigate whether moral behaviour can make up for a shortfall in government policy, we further begin with the assumption that the tax on the dirty good is below the socially optimal level, i.e. \(t<\hat{t} \), and therefore we also have \(\tilde{z} (t)>\hat{z}\).

The model of moral behaviour developed here assumes that individuals recognise that if they deviate from the consumption level \(\tilde{z} (t)\), they will incur a loss in personal welfare. This means that individuals still know that the rational choice for them and everyone else would be to choose \(\tilde{z} (t)\) (given the atomistic nature of consumption). However, they may also be driven by moral concerns for the environment and recognise that the overall outcome will be far from optimal for themselves and everyone else as long as the government continues to set the wrong tax. This may induce some individuals to act differently. Such an individual may measure a hypothetical moral value of deviating from the standard consumption level without expecting any personal benefit from this moral action.Footnote 28

Our model measures the hypothetical moral value of the choice through a type of ‘Kantian’ calculation as discussed in Sect. 2. This means that an individual with some propensity to act morally will assess how much better off they and everyone else would be if they and everyone else were to choose the same level of consumption, \(z\).Footnote 29 As already mentioned, the individual recognises that deviating will entail a cost to personal welfare, but may balance off this cost against the moral value, depending on their propensity to act morally. We assume that different types of individuals may differ in their propensity to act morally. Some individuals may only be concerned with the moral value of their action and not take any account of the loss of personal welfare they will incur. Yet other individuals may give no weight to the moral value but fully take account of the personal welfare cost associated with deviating from \(\tilde{z} (t)\). In addition to the propensity to act morally, the model recognises that individuals may still exhibit altruistic concern for others’ utility as modelled in the previous section. The previous results have shown that altruistic concern does not have any influence on the consumption choice under utility-maximising behaviour so the question arises whether this changes when individuals have some propensity to act morally.

The first step is to quantify the level of welfare loss associated with deviating from the initial consumption level. Let \(\zeta (t)\) be the assignment function that assigns everyone the initial level of consumption \(\tilde{z} (t)\). Therefore the average consumption of the dirty good is also \(\tilde{z} (t)\). For an individual of type k who gives altruistic weight \(\alpha \ge 0\) to the utility of other individuals, this gives an initial welfare level of

However, if the individual chooses a different level of consumption such that \(\hat{z}\le z\le \tilde{z} (t)\), but everyone else carries on consuming \(\tilde{z} (t),\) this generates the following level of welfare for the individual:

Combining (12) and (13) leads us to the welfare cost of choosing a different level of consumption of the dirty good, \(z\), as opposed to the initial level, \(\tilde{z} (t)\):

It is noteworthy that in the calculation of the welfare cost everything that depends on what the other individuals do, and therefore anything associated with the level of altruistic concern, has cancelled out. In addition, since an individual’s choice has no impact on the total level of emissions, the damage function has also cancelled out. The welfare cost is purely driven by the difference in the private benefit and cost elements of the dirty good. Were the individual to minimise this cost they would choose \(\phi ^{\prime }(z)=c+t\) and then we would be back at the standard level of consumption where \(z=\tilde{z} (t)\). Intuitively, in order to minimise the cost of deviating from the initial consumption level, one would not deviate at all.

The next step is to derive a measurement of the hypothetical moral value of choosing a different level of consumption. As already mentioned, this moral value is assessed by evaluating the welfare the individual would obtain if they and everyone else were to choose that same level of consumption. For an individual who places an altruistic weight \(\alpha \ge 0\) on the welfare of all other individuals this would yield the following level of welfare:

where \(\zeta ^{K}(z)\) is the ‘Kantian’ assignment function that assigns everyone else the same level of consumption of the dirty good as that chosen by the individual.

There are two factors the individual will incorporate when making this calculation. First, the individual sees that if they and everyone else choose the same level of \(z\), then the lump-sum transfer to the individual from the government tax revenues will equal the tax paid on the dirty good, rendering the tax rate irrelevant for the level of welfare obtained. Second, the individual takes account of the impact the choice of \(z\) has on total emissions and therefore the damage associated with it. Since it is a specific calculation of the level of welfare if everyone were to choose the same level of the dirty good, the individual effectively makes the same calculation a social planner would make. This means that the individual does not just evaluate the moral value for themselves, but also the benefit to everyone else in the population. Therefore, the moral value of choosing a level of consumption, \(z\), as opposed to the initial level, \(\tilde{z} (t)\), is

From here it is easy to see that were an individual to simply maximise the hypothetical moral value, the individual would choose the socially optimum level of consumption \(\hat{z}\) regardless of their level of altruistic concern for the utility of others.

We can now put together the moral value and welfare cost of deviating from the initial level by assuming an individual will make the consumption choice putting some weight on the moral value of deviating and balancing this off against the associated loss in personal welfare. Let this propensity to act morally be measured by \(\mu \). For simplicity we assume that individuals will choose their consumption by maximising the weighted difference between the moral value and the associated personal welfare cost:

Substituting (14) and (16) into (17), we see that for an individual with \(0\le \mu \le 1\), consumption of the dirty good will be chosen to

At this point it is noteworthy that, due to the linear nature of the choice function, the initial level of consumption \(\tilde{z} (t)\) is irrelevant to the consumption choice and could indeed be at any level.

Now, if we let

then it is straightforward to derive from (18) that the individual’s consumption choice can be characterised by

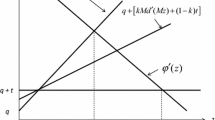

The parameter \(k\) is a combined parameter capturing both the individual’s propensity to act morally \(\mu \), and the level of altruistic concern for others’ utility \(\alpha \). This parameter can be thought of as the overall level of ‘virtue’ individuals may exhibit, where \(0\le k\le 1\). Examining (20), we see that if \(k=1\) the individual will choose a level of consumption equal to the socially optimal level \(z=\hat{z}=c+{\textit{MD}}^{{\prime }}(Mz)\). On the other hand, if \(k=0\), the individual will choose a consumption level of the dirty good equal to the conventional choice, \(z=\tilde{z}(t)=c+t\). Of course the level of \(k\) can be anywhere between \(0\) and \(1\) and the level of \(z\) will vary accordingly between \(\tilde{z} (t)\) and \(\bar{z}\). Figure 1 illustrates the potential level of consumption for an individual with a value of \(k\) such that \(0<k<1\).

Next, let us take a closer look at the determinants of \(k\). Suppose the individual has no altruistic concern for others’ utility (\(\alpha =0)\). Then it follows that \(k=\mu \). This means that for an individual with no altruistic concern, behaviour only depends on the their propensity to act morally. However, if \(\mu =1\), the individual will still cut down consumption of the dirty good to \(\hat{z}\) regardless of the level of \(\alpha \). Indeed we find that even if \(\alpha =0\), an individual with \(\mu >0\) will choose a lower consumption level of the dirty good relative to the standard level. It follows that altruistic concern for others’ utility is not a necessary component of this type of behaviour.

Now suppose that the individual has no propensity to act morally (\(\mu =0)\). Then, it is straightforward to see that \(k=0\) regardless of the value of \(\alpha \). Effectively, if \(\mu =0\), we are back to the case where people choose consumption of dirty good by maximising their welfare function which means that individuals will choose \(\tilde{z} (t)\) regardless of their level of altruistic concern. Using these insights, we can set out the next proposition.

Proposition 2

Altruistic concern for others’ utility is neither necessary nor sufficient to induce people to cut back consumption of the dirty good, but a propensity to act morally is both necessary and sufficient.

Proof

From (20) we know that \(z\) is a decreasing function of \(k\) for any \(t<\hat{t} \). From (19) we can further determine that if \(\mu =1 \rightarrow k=1\), if \(\mu =0 \rightarrow k=0\), and \(\frac{\partial k}{\partial \mu }=\frac{1+\alpha M}{(1+\mu \alpha M)^{2}}>0\) for any value of \(\alpha \). Therefore \(\alpha \) is neither necessary nor sufficient, but \(\mu \) is both necessary and sufficient to induce a decrease in \(z\).

However, let us now look at the case where individuals have some, but not full propensity to act morally (\(0<\mu <1)\). Then \(k\) is an increasing function of \(\alpha \). This means that the level of altruistic concern can affect the consumption choice even though people recognise that their consumption of the dirty good has no effect on total emissions and anybody else’s welfare. This is because, in calculating the hypothetical moral value of the action, people take into account their level of altruistic concern for others’ utility and therefore the impact their choice will have on everybody else’s utility, but the associated utility cost of the consumption choice is independent of the level of altruistic concern. Yet we should also note that, even if \(\alpha =1\), as long as \(\mu <1\), an individual will never cut down consumption of the dirty good all the way to \(\hat{z}\). This leads us to the next proposition:

Proposition 3

If individuals have some, but not full propensity to act morally, an individual with a higher level of altruistic concern for others will reduce consumption of the dirty good if the government sets the tax on the dirty good too low, but never all the way to the socially optimal level.

Proof

From (19) we can derive that \(\frac{\partial k}{\partial \alpha }=\frac{\mu M(1-\mu )}{(1+\mu \alpha M)^{2}}>0\) for any \(0<\mu <1\). Therefore \(k\) is an increasing function of \(\alpha \). Furthermore, we know from (20) that \(z\) is a decreasing function of \(k\) for any \(t<\hat{t}\). Therefore an increase in \(\alpha \) will lead to a reduction in the consumption of the dirty good for any \(0<\mu <1\). However, to achieve \(z=\hat{z}\), we require \(k=1\). As per the definition of \(k\) in (19), this is only the case when \(\mu =1\) and therefore \(z=\hat{z}\) can never be achieved for any \(0<\mu <1\) regardless of the value of \(\alpha \).

Next, suppose that the individual has some level of altruistic concern and some propensity to act morally (i.e. \(\alpha >0\), and \(\mu >0\)). Then we can see that \(k\) is also an increasing function of the size of the population, \(M\). It shows that the larger the population of people affected, the more people will cut back their consumption of the dirty good. The size of the population does not just influence the level of \(k\) though. Taking a closer look at (20) it is easy to see that for individuals with some propensity to act morally (i.e. \(k>0\)), there is another channel through which an increase in \(M\) will cause individuals to cut back their consumption of the dirty good. An increase in \(M\) increases the social marginal damage of consumption and therefore reduces the socially optimal level of consumption \(\hat{z}\).Footnote 30 The population size \(M\) impacts the social marginal damage because, (a) it increases the number of people affected, and (b) it increases the total level of emissions which leads to increasing marginal damage since damage is convex in \(z\) (ie \(D^{{\prime }{\prime }}>0)\). We can now state the following general proposition.

Proposition 4

If the government fails to set the tax that would be optimal given the usual economic behaviour and the usual conception as to what constitutes welfare, then, to the extent that individuals have some propensity to act morally, private action will to some extent compensate for the lack of government action and drive consumption of the dirty good down towards the optimal level.

Proof

For any \(0<\mu \le 1\) we have \(0<k\le 1\) as per the definition of \(k\) in (19). Using this and comparing (20) with (5) and (8), it is straightforward to see that we must have \(\phi ^{{\prime }}\left( {\hat{z}} \right) \ge \phi ^{{\prime }}\left( z \right) >\phi ^{\prime }[\tilde{z} (t)]\) and therefore we also know that \(\hat{z}\le z<\tilde{z} (t)\).

We further know that although people may behave according to a different set of rules, individuals’ welfare is still determined by the altruistic welfare function as defined in (10). The government recognises this and therefore still uses the same social welfare function given in (11) to determine the socially optimal allocation of welfare. Similarly, the social utility function \(S(.)\) is also still the same as described in (6). It is then straightforward to see that the socially optimal tax level for the government is still the standard Pigovian tax rate \(\hat{t} \), the same that would be optimal if the population had no propensity to act morally (i.e. \(\mu =0\) for all types). Indeed, by examining (20) while plugging in the Pigovian tax as shown in (9), we can easily determine that each individual will choose consumption level \(\hat{z}\) regardless of the level of \(k\). This means with a tax rate equal to \(\hat{t} \) we can still achieve the first-best solution where everyone consumes the same amount of the dirty good and the damage is fully internalised. This leads us to the final proposition.

Proposition 5

Although individuals may to some extent compensate for the government’s failure to set the optimal tax, this does not imply that the government should not set the optimal tax.

Proof

From (20) we can derive that by increasing \(t\) to \(\hat{t} ={\textit{MD}}^{{\prime }}\left( {M\hat{z}} \right) \) everyone will consume \(\hat{z}\) as characterised by (8). This raises social welfare because (a) aggregate consumption of the dirty good is socially optimal and (b) consumption is equalised across consumers.

Initially we assumed that the government set the tax on the dirty good below the optimal level (\(t<\hat{t} )\). Now suppose that the government actually sets the tax rate too high, so \(t>\hat{t} \) and therefore \(\tilde{z} (t)<\hat{z}\). Because the initial level of consumption is now lower than the socially optimal level, an individual with some propensity to act morally will actually increase their consumption of the dirty good in order to bring it closer to the socially optimal level. The benchmark for an individual with some propensity to act morally is always the socially optimal level of consumption and depending on the weight they give to the moral value, they will choose a consumption level of the dirty good that moves closer to \(\hat{z}\). This point illustrates that the propensity to act morally does not necessarily imply a reduction in the consumption of an environmentally harmful good. Rather, an individual with some propensity to act morally will change consumption in order to get closer to the social optimum in the absence of the correct tax on the dirty good.Footnote 31

4 Discussion

The aim of this paper was to develop an alternative model of moral behaviour and altruism in an environmental context and evaluate what implications such behaviour may have for environmental policy. We have shown that when people have some propensity to act morally they will cut back consumption of an environmentally harmful good. At the same time, altruistic concern for the utility of others can contribute to the amount that individuals cut consumption, but only if they also have some propensity to act morally. The optimal tax on the dirty good remains the same as under standard theory and the first-best solution can be achieved. A key reason for this is that, even though some individuals may cut consumption towards to socially optimal level for moral reasons, we are still only dealing with market failure, which the Pigovian tax can correct for all individuals. However, this result hinges on individuals correctly making the (sophisticated) calculation of the moral value when acting in this genuinely altruistic way. We mentioned earlier that the individual recognises both the link to the government budget constraint as well as the impact on total emissions when making this calculation. Suppose instead that the individual fails to take account of the connection to the government budget constraint. It is then straightforward to show that an individual with full propensity to act morally (\(\mu =1\rightarrow k=1)\) will actually overcompensate and consume less than the socially optimal level. At the same time, a tax at the Pigovian level means that every individual with some propensity to act morally (\(k>0)\) will consume less than the socially optimal level. Indeed, we are no longer able to find a tax rate that induces the first-best solution where everyone consumes the same amount of the dirty good. This is because we are now dealing with a behavioural failure as well as a market failure, which cannot both be corrected with a single instrument. We would need a separate mechanism to correct the behavioural failure.Footnote 32

Another key assumption in our model is that the propensity to act morally for each type of individual is a given and static parameter. There are two questions that develop from this observation. First, where does the propensity to act morally come from?Footnote 33 And second, can the propensity to act morally be influenced by extrinsic incentives on the dirty good? The latter addresses whether the propensity to act morally can be crowded-in or crowded-out by extrinsic incentives. Crowding of intrinsic motivation has received a lot of attention in the literature on pro-social behaviour due to its potential policy relevance.Footnote 34 Extensions to our paper could investigate how the model can be adapted to give further insights on this issue.

Notes

We will refer to this inability to influence the total level of the externality as ‘atomistic’ consumption.

Echoes of such free-riding behaviour can be found in a paper by Longo et al. (2012) reporting on a study conducted in the Basque Country on people’s willingness to pay for the ancillary benefits of climate change mitigation. They note that, as in many such studies, while many people reveal a positive willingness to pay, there is group of “protestors” who say they do not want to pay for these benefits, either because they do not think the proposed policy actions will be effective, or because they feel that others should contribute.

Johansson (1997) is not analysing a Kantian type of behaviour and therefore uses a different type of choice function that includes the individual’s and everybody else’s utility. He further assumes that all individuals are identical in terms of their degree of altruism or morality.

Also see Bergstrom et al. (1986).

Andreoni’s development of warm-glow giving is based on the analysis of the provision of impure public goods by Cornes and Sandler (1984). The analysis of impure public goods also has importance in the area of environmental policy. For example, Markandya and Rübbelke (2004) analyse ancillary benefits of climate policy and argue that policymakers should consider these more thoroughly. Further, Markandya and Rübbelke (2012) look at the under-provision of impure public technologies in an environmental context while Altemeyer-Bartscher et al. (2014) take into account that climate policy is an impure public good in their analysis of tax-transfer schemes in relation to international public goods. However, Impure Altruism and impure public goods are not the same concept. Impure public good means that the good itself has some private characteristics and this may impact individuals’ contribution to the public good. Whether a public good is a pure or impure public good depends on the characteristics of the good, and is independent of how the good is funded. However, Impure Altruism relates to the decision individuals make regarding the funding for the provision of the public good, and, in particular, to the relative weights they place on the benefits to themselves and to others in making that decision. For example, a public good may of a pure nature (i.e. both non-excludable and non-rivalrous) and confer no private benefits of the type mentioned above. An altruistic individual will value the benefits that the provision of this good brings to others but may, in addition, derive some utility gain (warm-glow) from knowing that they are taking an action (contributing) that gives benefits to others. The label ‘impure’ therefore refers to the nature of utility derived from an altruistic action, but not to the properties of the public good the individual is contributing to.

Also note that Andreoni refers to the case of an individual who only cares about the total supply of the public good as Pure Altruism. However, although the total supply of a public good also affects others, we, as well as other literature on altruism, use the term Pure Altruism to refer to an individual’s direct concern for the utility of others. We will provide a more detailed description of how we model Pure Altruism later in this section.

To some extent this also captures the idea of a social norm or peer pressure.

Because what matters in their model is the individual’s perception of what others do, Nyborg et al. (2006) further argue that policy makers may be able to influence this perception, for example through advertising. Also, a temporary tax on the environmentally harmful good could move the population to a permanent ‘green’ equilibrium even when the tax is later removed.

Another area of the literature where individuals may have utility gains from behaving in pro-environmental ways looks at individuals’ concern for relative consumption. An example relevant to the analysis of global public goods such as climate protection is the work by Aronsson and Johansson-Stenman (2014), who look at optimal provision of national and global public goods when individuals care about relative consumption levels.

The literature on altruism is very rich and we will only make a superficial survey as relevant to this paper. For more detail, Fontaine (2008) provides a summary of the history of the concept of altruism in economics.

Also see Nyborg and Rege (2003) for basic modelling approaches to public good provision including Pure and Impure Altruism.

See Johansson (1997).

Johansson (1997) uses a model of discrete, identical consumers, who choose between a ‘clean’ good and a ‘dirty’ good, which in turn causes the externality. The government imposes a tax on the dirty good, but tax revenues are distributed back to the consumer.

This result is driven by the assumption that the size of altruistic concern has to be small relative to the private consumption utility in order to maintain realistic proportionality of the utility function.

Furthermore, for Paternalistic Altruism Johansson (1997) finds that the tax is higher than the Pigovian tax because, as individuals take into account others’ experience of the externality, the socially optimally level of the externality is reduced and therefore the optimal tax level increases. For the case of Impure Altruism, the optimal tax is exactly equal to the Pigovian tax. Although the socially optimal level of consumption is lower than the standard level, this shift is exactly the amount that occurs due to the ‘warm glow’ from the individual’s contribution to the externality. Therefore, the optimal tax level does not need to be higher in order to achieve the socially optimal level of consumption.

Also see Bergstrom (2009) for a discussion of the links between moral rules and utility.

The model developed in this paper can also be thought of as capturing the idea of two different preference sets to some extent. However, combining two preference sets into a conventional model usually assumes that one supersedes the other or individuals follow certain rules (see Thaler and Shefrin 1981 for an example). The model we present in this paper assumes that individuals trade-off moral preferences against utility preferences depending on their propensity to act morally.

Sen (1977) also points out that the resulting behaviour may well be the same as the utility-maximising one, but that this may not have been the individual’s motivation.

White (2003) provides a good summary of the essentials of Kant’s philosophy as relevant to an economist and discusses linking it to the traditional model of economic behaviour.

Such an approach (a version of which is also used in our model) is generally inspired by Kant’s Formula of Universal Law (a version of the categorical imperative) which states: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.” (Kant 1875, p. 421).

This type of ‘Kantian’ calculation is similar to the one used by Brekke et al. (2003), although they link the moral value of this Kantian behaviour to a concern for self-image instead.

Although for simplicity reasons we assume that the degree of altruistic concern is the same for all individuals in the population, it is possible to generalise the result to allow for varying degrees of altruism for different types of individuals without affecting the main conclusions from our analysis.

Although individuals have identical utility functions, different types of individuals will later be defined by their propensity to act morally.

Income distribution is of course an important element in the analysis of environmental externalities. However, in order to isolate the effect of altruism and moral behaviour on individuals’ consumption choice, we have kept issues of income distribution out of this analysis.

This assumption makes it more straightforward to isolate the key drivers of behaviour when we develop the model of moral behaviour. It is, however, possible to allow the degree of altruism to vary across different types without altering the key results of this paper.

We will refer to the utility that includes the effect of altruistic concern as ‘welfare’. This is simply done to separate the direct type of utility from the altruistic type.

Note that this result does depend on the functional form used for the individual’s welfare function described in (10). However, this result can be generalised to other functional forms, for example the case where individual’s welfare takes the form \(w\left( {z;\zeta ,t,\alpha } \right) =U\left( {z;\bar{z} ,t} \right) [S\left( {\zeta ,t} \right) ]^{\alpha }\).

It is crucial to emphasize that moral value does not mean the individual derives any benefit (or utility) from the moral action.

This is of course a simplification of Kant’s Formula of Universal Law. For the purposes of this analysis, and in line with other literature using a Kantian approach as discussed in Sect. 2, we translate the categorical imperative in the sense that a Kantian calculation asks what would be optimal if everyone acted the same way (also see Laffont (1975); Brekke et al. (2003)).

This impact of M on the socially optimal level of consumption is of course not an exclusive feature of moral behaviour as modelled here, but can also be observed in the characterisation of the socially optimal level of consumption as shown in (8).

Buchholz et al. (2012) also analyse a case of public good provision where the subsidy may be too high.

See Shogren and Taylor (2008) for a discussion on the existence of both market and behavioural failures in an environmental economics context.

This question is researched in a number of disciplines including psychology, sociology, neuroscience and evolutionary biology (see for example Heinrichs et al. 2013 for a variety of contributions on moral motivation from different fields of research). Extensions to this paper could make more detailed links between the insights from those disciplines and the model developed in this paper.

References

Altemeyer-Bartscher M, Markandya A, Rübbelke DTG (2014) International side-payments to improve global public good provision when transfers are refinanced through a tax on local and global externalities. Int Econ J 28(1):71–93

Andreoni J (1988) Privately provided public goods in a large economy: the limits of altruism. J Public Econ 35:57–73

Andreoni J (1989) Giving with impure altruism: applications to charity and ricardian equivalence. J Polit Econ 97:1447–1458

Andreoni J (1990) Impure altruism and donations to public goods: a theory of warm-glow giving. Econ J 100:464–477

Archibald GC, Donaldson D (1976) Non-paternalism and the basic theorems of welfare economics. Can J Econ 9:492–507

Aronsson T, Johansson-Stenman O (2014) When Samuelson met Veblen abroad: national and global public good provision when social comparisons matter. Economica 81:224–243

Arrow KJ (1986) Rationality of self and others in an economic system. J Bus 59:385–399

Becker GS (1974) A theory of social interactions. J Polit Econ 82:1063–1093

Becker GS (1981) Altruism in the Family and Selfishness in the Market Place. Economica 48:1–15

Bénabou R, Tirole J (2006) Incentives and prosocial behavior. Am Econ Rev Econ Rev 96:1652–1678

Bergstrom T (2009) Ethics, evolution, and games among neighbors. The selected works of Ted C. Bergstrom 106:1–18

Bergstrom T, Blume L, Varian H (1986) On the private provision of public goods. J Public Econ 29:25–49

Brekke KA, Kverndokk S, Nyborg K (2003) An economic model of moral motivation. J Public Econ 87:1967–1983

Buchholz W, Cornes R, Rübbelke D (2012) Matching as a cure for underprovision of voluntary public good supply. Econ Lett 117:727–729

Cornes R, Sandler T (1984) The theory of public goods: non-nash behaviour. J Public Econ 23:367–379

Ellingsen T, Johannesson M (2008) Pride and prejudice: the human side of incentive theory. Am Econ Rev 98:990–1008

Fontaine P (2008) Altruism, history of the concept. In: Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) The new palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd edn. Palgrace MacMillan, London

Frey BS (1997) Not just for the money? An economic theory of personal motivation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Frey BS (1999) Morality and rationality in environmental policy. J Consum Policy 22:395–417

Galarraga I, Markandya A (2009) Climate change and its socioeconomic importance. Basque centre for climate change (BC3). Bilbao, Spain

Hammond PJ (1987) Altruism. In: Eatwell J, Milgate M, Newman P (eds) The new Palgrave: a dictionary of economics, 1st edn. Palgrace Macmillan, London

Harsanyi JC (1955) Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. J Polit Econ 63:309–321

Heinrichs K, Oser F, Lovat T (2013) Handbook of moral motivation: theories, models, applications, vol 1. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam

Johansson O (1997) Optimal Pigovian taxes under altruism. Land Econ 73:297–308

Kant I (1875) Grounding for the metaphysics of morals, 3rd edn. Hackett, Indianapolis

Kennett DA (1980) Altruism and economic behavior, I: developments in the theory of public and private redistribution. Am J Econ Sociol 39:183–198

Laffont J-J (1975) Macroeconomic constraints, economic efficiency and ethics: an introduction to kantian economics. Economica 42:430–437

Longo A, Hoyos D, Markandya A (2012) Willingness to Pay for ancillary benefits of climate change mitigation. Environ Resour Econ 51:119–140

Markandya A, Rübbelke DTG (2004) Ancillary benefits of climate policy. J Econ Stat 224(4):488–503

Markandya A, Rübbelke DTG (2012) Impure public technologies and environmental policy. J Econ Stud 39:128–143

Nyborg K, Rege M (2003) Does public policy crowd out private contributions to public goods. Public Choice 115:397–418

Nyborg K, Howarth RB, Brekke KA (2006) Green consumers and public policy: on socially contingent moral motivation. Resour Energy Econ 28:351–366

Sen AK (1977) Rational fools: a critique of the behavioral foundations of economic theory. Philos Public Aff 6:317–344

Shogren JF, Taylor LO (2008) On behavioral-environmental economics. Rev Environ Econ Policy 2:26–44

Stern N (2007) Stern review of the economics of climate change. HM Treasury, London

Sugden R (1982) On the economics of philanthropy. Econ J 92:341–350

Thaler R, Shefrin HM (1981) An economic theory of self-control. J Polit Econ 89:392–406

White MD (2003) Can homo economicus follow Kant’s categorical imperative? J Socio Econ 33:89–106

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Marc Daube gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/J500136/1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Daube, M., Ulph, D. Moral Behaviour, Altruism and Environmental Policy. Environ Resource Econ 63, 505–522 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9836-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9836-2