Abstract

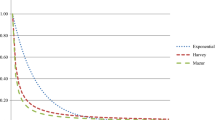

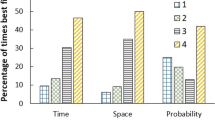

Environmental goods such as carbon abatement or green space development often generate benefit streams that may not occur until far into the future. How individual consumers value such amenities, therefore, depends critically on the discount rate. The usual assumption is that agents discount future values using constant, exponential rate, but there is some evidence from the lab suggesting that discount functions are more likely quasi-hyperbolic. We compare estimates of subjects’ rate of intertemporal time preference for financial rewards and environmental goods using multiple price-list and a new matrix multiple price list approaches. Our objective is to determine if discount functions for environmental and monetary goods differ, and to estimate the structure of discounting in both contexts. We find that financial discount functions are not hyperbolic, but those for environmental goods are. Discount rates for environmental goods are generally lower than for financial rewards, but are still above zero. Consumers, therefore, value long-lived environmental goods differently than financial goods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Cropper and Laibson (1999) and Karp (2005) explain, observed consumption paths of individuals with hyperbolic preferences can be explained by allowing them to play games with each of their “intertemporal selves.” The resulting consumption path for a finite-lived individual can be shown to be a unique, sub-game perfect equilibrium of these games and is observationally equivalent to the consumption path for an individual with exponential time preferences (Cropper and Laibson 1999).

Weikard and Zhu (2005) argue for “dual discounting” or the application of different discount rates for environmental and consumption goods, and provide a theoretical rationale for why dual discounting is appropriate.

It is important to note that students may graduate and some may move from the region before the green space is restored making it highly unlikely that they would benefit from the improvements. That said, the majority of the student-subjects are local and intend to stay in the Puget Sound area.

Previous research shows that 24 months is sufficient to identify the hypothesized curvature in the discount function. Benhabib et al. (2010), for example, use a maximum horizon of 6 months. Any longer than 24 months and the incentive-compatibility of our experimental design would no longer be credible.

Note that these interest rate calculations were not shown to subjects on their choice screen, but are revealed in Table 1 to show the exact discount rates implied by each choice.

Ideally, or maximum delay would be longer than 24 months to identify truly long-term discount rates. However, decisions regarding rewards more than 2-years out are no longer plausibly incentive compatible as subjects are not likely to expect payment after a 2-year delay.

Similar to the MPL, subjects may also exhibit “multiple switch points” (Andersen et al. 2006a) by moving among columns as they move down. However, as Andersen et al. (2006a) explain, such behavior may be due to the subject being indifferent between the options presented, and that the only requirement is that the responses exhibit consistency on average over the responses. Viewed from the perspective of utility theory, “...preferences are only required to be weakly convex rather than strictly convex...” (Andersen et al. 2006a).

The three charitable organizations are: Seattle Parks Foundation for park restoration, Puget Soundkeeper Alliance for storm water quality, and Bonneville Environmental Foundation for reductions of carbon emissions. Each non-profit was detailed at the beginning of the appropriate section of the survey.

This development is based on Benhabib et al. (2010).

Benhabib et al. (2010) specify and estimate perhaps the most general empirical model, but find that their nesting parameter is estimated imprecisely in nearly all specifications with individual-level models. It is not clear from their data how their data are able to identify the separate fixed- and variable-cost effects that they report.

Using the decreasing impatience (DI) criteria for a discount function to capture hyperbolic discounting, it is straightforward to show that the function we choose exhibits DI for \(\alpha >1\), but not for \(\alpha <1.\) Specifically, the second derivative of the log-discount function in our case is \(d^{2}\ln D/dt^{2}=-\alpha (\alpha -1)\delta _{h}t^{\alpha -2},\) which is only negative when \(\alpha >1.\)

This factor is also akin to the “...additive constant...” of Becker and Mulligan (1997).

A reviewer points out that these behaviors are well-known to be addictive, so may be out of the subject’s control. However, according to the rational addiction model of Becker and Murphy (1988), addictive behaviors are fully consistent with individuals who maximize utility, have stable preferences, and discount the future in a rational way. Our including these variables in the model rests on this assumption.

The first-stage function, estimated with non-linear least squares, also consists of a constant term and discount-rate estimate. These parameters, each of which are statistically significant, are available upon request.

References

Andersen S, Harrison GW, Lau MI, Rutstrom EE (2006a) Elicitation using multiple price list formats. Exp Econ 9:383–405

Andersen S, Harrison GW, Lau MI, Rutstrom EE (2006b) Valuation using multiple price list formats. Appl Econ 39:675–682

Andersen S, Harrison GW, Lau MI, Rutsrom EE (2008) Eliciting time and risk preferences. Econometrica 76:583–618

Andreoni J, Sprenger C (2012) Risk preferences are not time preferences. Am Econ Rev 102:3357–3376

Arrow KJ, Cline WR, Maler K-G, Munasinghe M, Squitieri R, Stiglitz JE (1996) Intertemporal equity, discounting and economic efficiency. In Bruce JP, Yi H-S, Haites EF (eds) Climate change 1995: economic and social dimensions of climate change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group III. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK

Arrow KJ, Dasgupta P, Goulder L, Daily G, Ehrlich P, Heal G, Levin S, Maler K-G, Schneider S, Starrett D, Walker B (2004) Are we consuming too much? J Econ Perspect 18:147–172

Becker G, Mulligan C (1997) The endogenous determination of time preference. The Q J Econ 112:729–758

Becker GM, Murphy KM (1988) A theory of rational addiction. J Polit Econ 96:675–700

Benhabib J, Bisin A, Schotter A (2010) Present-bias, Quasi-hyperbolic discounting, and fixed cost. Games Econ Behav 65:209–223

Bohm G, Pfister H (2005) Consequences, morality, and time in environmental risk evaluation. J Risk Res 8:461–479

Cameron AC, Trivedi P (2005) Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Carson RT, Groves T (2007) Incentive and informational properties of preference questions. Environ Resour Econ 37:181–210

Chapman G (1996a) Temporal discounting and utility for money and health. J Exp Psychol 22:771–791

Chapman GB (1996b) Expectations and preferences for sequences of health and money. Org Behav Hum Decis Process 67:59–75

Cropper M, Laibson D (1999) The implications of hyperbolic discounting for project evalulation. Resources for the Future Working paper, Washington

Cutler DD, Glaeser EL (2005) What explains differences in smoking, drinking and other health related behaviors? Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 95:238–242

Gattig A, Hendrickx L (2007) Judgmental discounting and environmental risk perception: dimensional similarities, domain differences, and implications for sustainability. J Soc Issue 63:21–39

Hardisty DJ, Weber EU (2009) Discounting future green: money versus the environment. J Exp Psychol Gen 138:329–340

Harrison GW, Lau MI, Williams MB (2002) Estimating individual discount rates for Denmark: a field experiment. Am Econ Rev 92:1606–1617

Harrison GW, Lau MI, Rutstrom EE, Sullivan MB (2005) Eliciting risk and time preferences using field experiments: some methodological issues. In: Carpenter J, Harrison GW, List JA (eds) Field experiments in economics Greenwich, 10th edn. JAI Press, Research in Experimental Economics, CT

Hendrickx L, Nicolaij S (2004) Temporal discounting and environmental risks: the role of ethical and loss-related concerns. J Environ Psychol 24:409–422

Hoel M, Sterner T (2007) Discounting and relative prices. Clim Change 84:265–280

Karp L (2005) Global warming and hyperbolic discounting. J Public Econ 89:261–282

Laibson D (1997) Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Q J Econ 112:443–477

Loewenstein G, Prelec D (2002) Anomalies in intertemporal choice: evidence and an interpretation. Q J Econ 107:573–597

Lusk JL, Schroeder TC (2004) Are choice experiments incentive compatible? A test with quality differentiated steaks. Am J Agric Econ 86:467–482

Miller KM, Hofstetter R, Krohmer H, Zhang ZJ (2011) How should consumers’ willingness to pay be measured? An empirical comparison of state-of-the-art approaches. J Mark Res 48:172–184

Nicolaij S, Hendrick L (2003) The influence of temporal distance of negative consequences on the evaluation of environmental risks. In: Hendrickx L, Jager W, Steg L (eds) Human decision making and environmental perception. Understanding and assisting human decision making in real-life situations. University of Groningen, Groningen

Nordhaus WD (1994) Managing the global commons: the economics of climate change. MIT Press, Cambridge

Phelps ES, Pollak RA (1968) On second-best national saving and game equilibrium growth. Rev Econ Stud 35:185–199

O’Donoghue T, Rabin M (1999) Doing it now or later. Am Econ Rev 89:103–124

Prelec D (2004) Decreasing impatience: a criterion for non-stationary time preference and “hyperbolic discounting”. Scand J Econ 106:511–532

Svenson O, Karlsson G (1989) Decision-making, time horizons, and risk in the very long-term perspective. Risk Anal 9:385–399

Train, KE (2003) Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge University Press

Thaler RH (1981) Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Econ Lett 8:201–207

Viscusi WK, Huber J, Bell J (2008) Estimating discount rates for environmental quality from utility-based experiments. J Risk Uncertain 37:199–220

Weikard H-P, Zhu X (2005) Discounting and environmental quality: when should dual rates be used? Econ Model 22:868–878

Weitzman ML (1998) Why the far-distant future should be discounted at its lowest possible rate. J Environ Econ Manag 36:201–208

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richards, T.J., Green, G.P. Environmental Choices and Hyperbolic Discounting: An Experimental Analysis. Environ Resource Econ 62, 83–103 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9816-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9816-6