Abstract

Existing studies have measured the effect of video-based feedback on student performance or satisfaction. Other issues are underacknowledged or merit further investigation. These include sociocultural aspects which may shape the design and implementation of video-based feedback, the ways students use technology to engage in feedback, and the processes through technology may transform learning. This study investigates the design and implementation of a video-annotated peer feedback activity to develop students’ presentation skills and knowledge of climate science. It explores how their use of a video annotation tool re-mediated established feedback practices and how the systematic analysis of contradictions in emerging practices informed the subsequent redesign and reimplementation of the approach. Employing a formative intervention design, the researchers intervened in the activity system of a first-year undergraduate education module to facilitate two cycles of expansive learning with an instructor and two groups of Hong Kong Chinese students (n = 97, n = 94) across two semesters. Instructor interviews, student surveys, and video annotation and system data were analysed using Activity Theory-derived criteria to highlight contradictions in each system and suggest how these could be overcome. The findings highlight the critical importance of active instructor facilitation; building student motivation by embedding social-affective support and positioning peer feedback as an integrated, formative process; and supporting students’ use of appropriate cognitive scaffolding to encourage their interactive, efficient use of the annotation tool. Conclusions: In a field dominated by experimental and quasi-experimental studies, this study reveals how an Activity Theory-derived research design and framework can be used to systemically analyse cycles of design and implementation of video-annotated peer feedback. It also suggests how the new activity system might be consolidated and generalised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Feedback is critical to learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2016; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). It has been defined as a process in which students make sense of information from external sources and use this to enhance their work or learning strategies (Carless & Boud, 2018). In contrast, others have conceptualised it as an internal process that involves students monitoring, evaluating and regulating their learning (Nicol, 2019). Evaluating and commenting on the work of others can help students to reflect and generate feedback on their own performance (Nicol, 2019), and develop evaluative judgement (Ajjawi et al., 2018; Tai et al., 2017).

For six decades, video has been used to facilitate feedback on communication skills in a broad variety of disciplines (Hammoud et al., 2012). Traditionally, such approaches have been instructor-led, with instructors controlling the technology and directing feedback processes in in-person learning environments (Fukkink et al., 2011). More recent innovations enable students to record themselves and engage in feedback asynchronously, online, using annotation tools to insert time-stamped comments in specific parts of a recording (Evi-Colombo et al., 2020; Hulsman & van der Vloodt, 2015).

Studies on the use of video for peer feedback tend to focus on the effectiveness of approaches in terms of their impact on student performance or satisfaction. However, other issues are underacknowledged and merit further investigation. Existing literature does not take account of sociocultural factors which can shape the design and implementation of video-based peer feedback, the ways students use technology to engage in these activities, or the ways technology may transform learning. These underacknowledged aspects are crucial in designing effective video-based feedback practices that can promote students’ learning and engagement. Investigating the sociocultural factors that shape the design and implementation of video-based feedback and understanding how students use technology to engage in video-based feedback can help inform the development of feedback practices that align with students’ learning needs and preferences, transforming their learning experience.

This study investigates the design and implementation of a video-annotated peer feedback activity to develop students’ presentation skills and knowledge in an undergraduate general education module in a large public university in Hong Kong. In the activity, students worked in groups to develop a video proposal for a group project. They then used a video annotation tool to provide peer feedback on videos created by other groups. Using Activity Theory and the related concept of expansive learning (Engeström, 2001, 2015), this study analyses how students’ use of the tool transformed or re-mediated traditional feedback practices in Semester 1, 2021–22. It then explores how systematic analysis of contradictions informed the redesign and reimplementation of this approach in Semester 2. It concludes with recommendations for future changes to help instructors to generalise and consolidate video-annotated peer feedback in higher education, further enhancing the approach. In providing insights into the design and implementation of video-based feedback practices, it aims to fill important gaps in the literature. These are highlighted in the following section.

2 Literature review

2.1 Instructor feedback and sequencing

In the existing literature on video-based feedback there is little agreement around the value of instructor feedback and its impact on peer commenting. Several studies have found that while students often value instructor comments more highly than those of their peers, the two sources of feedback can complement each other and support learning (Ritchie, 2016; Simpson et al., 2019; Yoong et al., 2023b). Such studies recommend that instructors provide feedback before peer commenting, so that students can use the peer feedback process to make sense of instructor feedback (Simpson et al., 2019) and offer more personalised feedback than instructors can provide (Yoong et al., 2023a, b). Against this, Murillo-Zamorano and Montanero (2018) argue that instructor feedback can be of limited benefit when compared with video-based peer feedback. The authors conclude that students are more likely to critically reflect on their own work if it has been assessed by a peer, as opposed to an instructor-expert, since comments are more likely to be concise and easy to grasp. Indeed, in Leger et al.’s (2017) study, students reported the same levels of satisfaction and achieved the same learning outcomes when instructor feedback was replaced with peer commenting. The role of the instructor in providing feedback is therefore worthy of further exploration.

2.2 Cognitive scaffolding

There is broad agreement in the literature around the importance of cognitive scaffolding. Particular attention is paid to the role of rubrics in developing students’ feedback literacy and evaluative judgement (Ritchie, 2016) or improving the specificity of peer comments (Anderson et al., 2012), as well as the need to provide instructions and advice to ensure students understand and apply them (Hsia et al., 2016; Nagel & Engeness, 2021; Yoong et al., 2023a, b). Other works stress the benefits of combining rubrics with additional scaffolds, such as training courses, in which students learn about peer feedback (Lai et al., 2020; Li & Huang, 2023) or practise using the rubric to evaluate self-introduction videos or exemplars (Murillo-Zamorano & Montanero, 2018; Zheng et al., 2021). Others still call for alternative scaffolds, such as a peer review form, to invite more open comments (Davids et al., 2015); guided in-person discussions, to foster students’ analytical and reflective skills (Admiraal, 2014); or instructor prompts, to encourage spontaneous discussion (Hunukumbure et al., 2017). In each case, however, the interaction of cognitive scaffolding with the wider sociocultural context is underexplored.

2.3 Motivation

Several studies have explored the impact of grading, or the absence of grading, on motivation. Most scholars agree that students who engage in video-based peer feedback tend to be internally motivated rather than grade-oriented. However, the source of this motivation is unclear. Motivation may derive from a desire to perform better in future summative assessments (Simpson et al., 2019; Toland et al., 2016), perceived improvements in communication skills (Krause et al., 2022), or the satisfaction or challenge of peer review (Hsia et al., 2016). In addition, if the process is formative, and ungraded, students are likely to perceive it as less stressful and therefore more motivating (Yoong et al., 2023b). Nevertheless, it has been argued that grading may play an important role in motivating low-ability students (Nikolic et al., 2018).

Others highlight the impact of affective factors on students’ motivation to engage in video-based peer feedback. These include anxiety and stress (Lewis et al., 2020; Smallheer et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2021), distress (Hunukumbure et al., 2017), vulnerability (Colasante, 2011), fear and intimidation (Näykki et al., 2022), and shame (Herrmann-Werner et al., 2019). However, there is less consensus on how these factors can be mitigated. Studies advocate, on the one hand, in-class peer dialogue (Admiraal, 2014) with the presence of supportive and respectful peers and instructors (Lewis et al., 2020) and, on the other hand, the absence of instructors (Smallheer et al., 2017), or a reduced number of peers (Colasante, 2011). The role of grading, instructor presence and peer group size is worthy of further investigation.

2.4 Efficiency, specificity and feedforward

In the literature there are two strands of opinion on the efficiency of video-annotated peer feedback approaches. The first argues they are more efficient than non-annotated approaches, despite additional student workload, since they result in more deliberate and solutions-focused commenting and more peer feedback overall (Lai et al., 2020). In promoting more specific, contextualised commenting, they can reduce the time students would otherwise spend searching recordings for events that correspond to the feedback provided (Leung & Shek, 2021) and minimise primacy and recency bias (Shek et al., 2021). The second says that video-annotated peer feedback is more cognitively challenging for less experienced or lower-ability students, leading to low engagement (Fadde & Sullivan, 2013; Li & Huang, 2023). For these students, simplified, instructor-guided viewing is likely to be more productive than relying on inherent features of the tool (Fadde & Sullivan, 2013).

Existing works are also divided on the factors that generate specificity and feedforward in video-annotated approaches, with this again attributed to, on the one hand, certain characteristics of the tools (Baran et al., 2023; Rich & Hannafin, 2009), or, on the other, cognitive scaffolds, such as observing or assessing sample videos (Ellis et al., 2015).

2.5 Interactivity, guidance and structure

In the existing literature there is a broad consensus on the interactive, participatory and collaborative nature of video-annotated peer feedback. This is attributed to students being able to author specific, time-stamped comments, resulting in open, authentic communication and critical, constructive feedback (Leung & Shek, 2021); the environment is more interactive as it is less face-threatening, with fewer cultural barriers to knowledge exchange (Evi-Colombo et al., 2020). However, to cultivate interactivity, instructors must both facilitate and contribute to critical dialogue (Shek et al., 2021) and share guidance on giving and receiving constructive feedback (Colasante, 2011; Ellis et al., 2015). It is also suggested that video-annotated peer feedback is more likely to be interactive if it is structured (Näykki et al., 2022; Pless et al., 2021). What is unclear in the literature is the required nature and extent of this guidance and structure.

2.6 Problem statement and research questions

Literature on the use of video and video annotation tools for peer feedback is dominated by experimental and quasiexperimental studies. These cannot take account of the rich variety of interconnected sociocultural factors discussed above, which combine to shape the design of video-based peer feedback activities and students’ experiences of their implementation. In understanding the complex nature of students’ experiences, it is also important to move beyond measures of evaluation based on satisfaction, acceptance and effectiveness in improving performance, and instead examine how students use technology to engage in peer feedback. The themes of efficiency, specificity, and interactivity in experiences of video-annotated peer feedback also merit further exploration. However, rather than seeking deterministic, causal links between these themes and students’ use or non-use of video annotation, the relationships between these themes should be systematically analysed, taking into account the sociocultural context, to understand how student experiences of peer feedback may be re-mediated through their use of the tool. Our first research question is therefore:

-

RQ 1. How does the design and implementation of a video-annotated peer feedback activity to develop students’ presentation skills re-mediate a culturally entrenched activity system?

Our analysis of the literature has highlighted multiple conflicts and tensions in sociocultural factors that shape students’ use of video-based peer feedback, each of which merits further investigation. It is clear that these factors are complex and interrelated, and cannot be studied in isolation; to uncover the contradictions within and between them and explore how these might be overcome in practice, systemic analysis is needed. Similarly, the themes of efficiency, specificity and interactivity, which relate to students’ experiences of video-annotated peer review, are also intertwined. Far from being technologically determined by students’ adoption of an annotation tool, these concepts emerge through the nuanced interplay of the tool with the sociocultural factors outlined above and the systemic contradictions that may be generated. Our second and third research questions are therefore:

-

RQ 2. What systemic contradictions may be generated in the design and implementation of the video-annotated peer feedback activity?

-

RQ 3. How might these contradictions be overcome in future versions of the activity?

3 Theoretical framework

3.1 Activity theory as an analytical tool

Our study uses Activity Theory (Engeström, 2001, 2015) as a framework to analyse the design and implementation of video-annotated peer feedback. It is well suited to researching technology enhanced learning because it can provide a focused perspective on learning contexts, exposing underlying interactions and contradictions to help understand learning technology use (Scanlon & Issroff, 2005). It can reveal how tools shape, or mediate, the way subjects interact with objects within a complex social environment (Bligh and Flood, 2015) .

The activity system, depicted in Fig. 1, is a ‘unit of analysis’ for object-oriented activity. It consists of six interconnected components:

-

subject: the individual or group whose position is chosen as the perspective of the activity-theoretical analysis

-

object: the motive or problem at which the activity is directed

-

tools: the artefacts or instruments that mediate subject-object interaction, turning the object into an outcome

-

community: the individuals and subgroups who share the same general object

-

division of labour: the horizontal division of tasks and responsibilities and vertical division of status and power

-

rules: the explicit or implicit ‘regulations, norms, conventions and standards that constrain actions’ within the activity system (Engeström & Sannino, 2010, p. 6).

In the context of this study, the subject is the student, working towards the object of developing presentation skills, with their activity mediated by tools such as learning technologies and language. Their interactions with the community of peers, facilitated by the instructor, are mediated by rules covering how feedback is given, grading policies and institutional guidelines. The actions of the community are mediated by the division of labour, which determines who is responsible for giving feedback (the instructor, students or both) and whose feedback is seen as the most authoritative.

3.2 Expansive learning

Our study is underpinned by Engeström’s (2015) notion of expansive learning. Expansive learning affords an understanding of how contradictions in social organisations, and participants’ ability to overcome these contradictions, can drive change and development. Contradictions can appear as:

-

primary, within individual parts of the activity system (e.g. in the division of labour);

-

secondary, between two or more nodes (e.g. between a new object and an old tool);

-

tertiary, between a newly established activity and the remnants of a previous mode of activity; or

-

quaternary, between the newly reorganised activity and neighbouring activity systems (Engeström & Sannino, 2010).

Contradictions can drive expansive learning when used as opportunities to identify and develop a new, expanded object and new activity oriented to the new object. Moving from the abstract theoretical concept of the new object to the concrete new activity is achieved through a cycle of specific expansive learning actions (Engeström, 2001). In their ideal form, these actions are:

-

1.

Questioning: challenging, criticising, rejecting some aspects of the accepted practice and existing wisdom;

-

2.

Analysis: historical, to trace the origins and evolution of the situation, and actual-empirical, to explain it by constructing a picture of its inner systemic relations;

-

3.

Modelling: constructing an explicit simplified model of a new explanatory relationship offering a solution to the problematic situation;

-

4.

Examination: running, operating, and experimenting on the model to understand its dynamics, potential or limitations;

-

5.

Implementation: applying the model in practice, enriching and extending it;

-

6.

Process reflection: reflecting, evaluating the process;

-

7.

Consolidation and generalisation: consolidating the outcomes into a stable form of practice (Engeström, 1999; Engeström & Sannino, 2010).

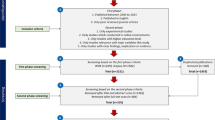

Figure 2 (Engeström, 1999), a diagrammatical representation of the ‘ideal–typical’ expansive learning cycle, highlights how successively evolving contradictions are constructed and resolved, leading to consolidation of new practices (Engeström & Sannino, 2010).

Sequence of actions in an expansive learning cycle (Engeström, 1999). Licence at CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

In using expansive learning in this study, we sought to work with the instructor to develop changes in the object of activity, resulting in a qualitative transformation of all components of the activity system. This would enable us to provoke their reflections on the process, allowing new peer feedback practices to be consolidated and generalised.

3.3 Activity theory-derived criteria for evaluating learning technology use

To analyse the re-mediation of the existing activity system of developing a group project proposal and highlight contradictions in the implementation of video-annotated peer feedback, this study uses Scanlon and Issroff’s (2005) Activity Theory-derived criteria for evaluating learning technology use:

-

Interactivity: How does the novel tool meet subjects’ expectations about interactions between students and instructors (rules) and the division of responsibilities between students and instructors (division of labour)?

-

Efficiency: How can participants use the novel tool to achieve desired outcomes without wasting time or effort?

-

Serendipity: How can subjects’ expectations (rules) affect their perceptions of any accidental discoveries made using the novel tool and how can this influence the dynamics of control (division of labour)?

-

Cost: How do the perceived costs of using the novel tool change the rules of practice?

-

Failure: How can unforeseen problems with the tool affect subjects, the community, rules of engagement or the division of labour? (Scanlon & Issroff, 2005, pp. 434–436)

Like Activity Theory and expansive learning, the evaluation criteria focus on building an understanding of the culture and context of the learning situation. They aim to expose hidden connections and relationships in complex activity systems, paying close attention to sociocultural factors, in order to change teaching and learning practices (Scanlon & Issroff, 2005).

4 Methods

Our research uses a formative intervention design, where participants expansively transform the object of their activity to face historically formed contradictions (Sannino et al., 2016). We intervene in the activity system of an undergraduate general education module to facilitate two cycles of expansive learning.

4.1 Participants, context, and setting

The research setting is a large, public HE institution which was given university status in 1994. The context is a general education module which ‘aims to nurture students’ intellectual capacity, global outlook, communication and critical thinking skills from a multi-disciplinary perspective’ (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, n.d.). The module addresses the issue of climate change. While most students are in Year 1, it is open to undergraduate students from any year of study or subject background. Students’ final grade is based on a project in which students form groups to research a topic of their choice. This involves developing a group proposal and giving a group presentation.

The module was taught by a single instructor, T, to separate groups of students in Semester 1 (n = 97) and Semester 2 (n = 94), 2021–22. T and students were Hong Kong Chinese. In Semester 1, students’ ages ranged from 18 to 21 years (M = 19.7, SD = 3.1), with 53% identified as female. In Semester 2, the age range was 18 to 23 years (M = 20.4, SD = 3.7) with 51% identified as female.

4.2 Research instruments, data collection and procedure

Research instruments included instructor interviews, student surveys, and video annotation and system data. Each of these helped to facilitate expansive learning, as shown in Fig. 3.

4.2.1 Interviews

In Cycle 1, the first of two instructor interviews addressed the stages of questioning, analysis, modelling and examination. Using a semi-structured interview protocol, it explored T’s existing approach to giving feedback on student presentations and the possible problems or challenges involved in this approach. In the same interview, a new activity system in which students’ activity was re-mediated by a video annotation tool was then modelled and examined. The questions were each linked to expansive learning actions and included the following:

-

Questioning: How do students currently receive feedback on their presentation skills in your module? What challenges do they currently experience?

-

Historical analysis: How did this approach to feedback develop?

-

Modelling: How will engaging in video-annotated peer feedback change their learning experience?

-

Examination: How will it work in practice? What challenges might students face in giving and receiving peer feedback using uRewind?

Following implementation, T took part in a second interview focusing on process reflection and consolidation and generalisation. Questions included:

-

Process reflection: What were your overall impressions of how the students used uRewind for peer feedback? What worked well? What did not work so well?

-

Consolidation and generalisation: Would you like to use uRewind again in this module? If so, what would you do differently to ensure the activity was successful?

In Cycle 2, the first interview was used to model and examine an improved activity system. Following implementation, in the second interview, T again reflected on the process and discussed how the model could be generalised and consolidated.

4.2.2 Surveys

In each learning cycle, two student surveys were used. These consisted of eight open-ended questions, as used in previous studies (Gatrell, 2021, 2022), to address different expansive learning actions. The first survey supported questioning and analysis, by exploring the problems and challenges that students might have been experiencing in developing their presentation skills, and modelling and examination, by asking them to think about how the tool might work in practice as part of their peer feedback process and consider its potential and limitations. Questions included:

-

Questioning: What challenges are you currently experiencing in developing your presentation skills?

-

Examination: What do you think you could gain from using uRewind to give peer feedback on other students’ presentations?

In each learning cycle, survey data was then incorporated into models of the planned re-mediated activity systems to further support modelling and examination.

Following implementation, the second survey was used to gather data on students’ perceptions of using the novel annotation tool to engage in peer feedback, to support process reflection and consolidation and generalisation. Questions included:

-

Process reflection: How did using uRewind to engage in peer feedback help you to develop your presentation skills? How else did it benefit you?

-

Consolidation and generalisation: If you did the video-based peer feedback activity again, what aspects of the activity design would you change?

4.2.3 Video annotations and system data

Time-stamped feedback annotations were downloaded to show students’ actual use of the tool. Learning analytics were also downloaded from the video platform, showing the videos students had viewed and the number of minutes they had spent watching them.

4.3 Data analysis

Data from the interviews and surveys was analysed using MAXQDA2022. Transcripts and student responses were assigned codes based on the expansive learning actions and evaluation criteria they related to. In Cycle 1, the coded data was used to represent and then identify problems in the historical system. It was then used to construct and understand the potential and limitations of the new activity system. Finally, it was used to explain students’ experiences of video-annotated feedback in Semester 1 in terms of the evaluation framework, highlighting contradictions in the new activity system. In Cycle 2 the coded data was used to model and examine an improved system, in which the contradictions were resolved. It was then used to explain students’ experiences of video-annotated feedback in Semester 2, highlighting new contradictions that had emerged or old contradictions that had not been addressed. The findings at each implementation stage were triangulated with analysis of annotation and system data. This data revealed the level of interactivity between students and the efficiency of their tool-mediated activity, measured in terms of the specificity of their annotations, words posted, videos viewed, and time spent. To analyse feedback specificity, student annotations were coded using retrospective categories of behaviour, motive, and effect, and prospective categories of suggesting alternative behaviour or describing goals: the proposed consequence of alternative behaviours (Hulsman & van der Vloodt, 2015). The categories were used to identify individual feedback units within comments. These were then counted to provide three measures: a specificity score, showing the total categories addressed in all comments by the same student; the balance the student achieved between the five categories; and a specificity rating for each comment reflecting how many of categories it addressed.

5 Results

This section presents two cycles of expansive learning. It begins with questioning and analysis of the historical activity system of developing a group project proposal, DGPP0. This is followed by modelling and examination of the re-mediated system, DGPP1. It then analyses students’ experiences of how DGPP1 was implemented in Semester 1, identifying how their practices were re-mediated by the annotation tool. The report then illustrates how student and instructor (T) reflections on the process helped to identify contradictions, which informed the second cycle of expansive learning, in Semester 2. It analyses the modelling, examination, and implementation of DGPP2, a more advanced system. It concludes with student and instructor reflections on this process, highlighting further contradictions in the model. The two cycles are shown in Fig. 3.

5.1 Cycle 1: Questioning and analysis

T reflected on the questioning process that had led him to introduce the annotation tool. This made it possible to analyse the historical system DGPP0, identifying three contradictions. These are outlined below and shown in Fig. 4.

Representation of DGPP0, the historical system. Three contradictions are shown: 1. Secondary contradiction between tools and rules: Monitoring participation and the ‘free rider’ problem; 2. Secondary contradiction between community and rules: Limits to ideas exchange and interaction in a changed learning environment; 3. Secondary contradiction between subject and tools: Preference for videos over text

5.1.1 Monitoring participation and ‘free riders’

One key form of questioning that T reported addressed the problem of monitoring participation. Historically students had worked in groups to write a proposal, using Microsoft Word, which they submitted by email for instructor feedback. Though students were asked to state which parts of the proposal they had contributed, it was not always clear who had participated. Students complained of ‘free riders’, members who achieved a grade without contributing to the proposal.

5.1.2 Limits to ideas exchange and interaction online

T explained that the group-based nature of the activity had been shaped by institutional policies:

It’s designed to meet the learning outcomes of general education module: teamwork, develop communication skills, lifelong learning, and social responsibility. I feel a group project is important for them to develop these characteristics. (T, Interview 1a)

He believed that exchanging ideas with peers would be of particular benefit to these students, given the heterogeneity of their subject backgrounds and lack of scientific knowledge.

In early 2020, COVID and the sudden institutional shift to online learning presented challenges to established practice. It became impossible for students to meet in person to exchange ideas around their topics and challenging for them to establish relationships with their group members. This compounded the challenges many students were already experiencing in doing group-based independent research: sourcing relevant, accurate information and supporting evidence, and combining multiple independent parts into a coherent proposal.

In online learning environments, students were found to be less interactive than in traditional classroom settings:

If I ask questions, only a few of them respond. In the classroom they used to speak up, even in a group of 100, but online they just type in the chat. They don’t turn on their microphone. (T, Interview 1a)

Even if students successfully submitted their proposals in writing, they would still need to present their finished research projects to the cohort. T feared that this would prove challenging without opportunities to practise with their group.

5.1.3 Student preferences for video over text

Students appeared less engaged in text-based activities. As T reflected, they expected to not only acquire subject content but also co-create content through video:

It seems this generation of students don’t like reading text and using discussion forums may be a bit boring for them. I think video may have a stronger impact on them. (T, Interview 1a)

5.2 Cycle 1: Modelling and examination

During 2020–21, T had begun exploring the use of video-based peer feedback to develop group project proposals, to address the challenges he had experienced. The new and more culturally advanced activity system, DGPP1, became the focus of modelling and examination in Cycle 1. It is shown in Fig. 5.

5.2.1 Peer learning, proving participation and practice

Using video rather than text for the activity would resolve several contradictions in DGPP0. It would require students to meet synchronously online in videoconferencing platforms to exchange ideas and then record themselves. This would create opportunities for peer learning. It would also address the ‘free rider’ problem, by providing ‘evidence they all participated in developing the proposal’. In addressing generational learning preferences for video content-creation, it would offer students additional practice in presenting their ideas in English, online, before the assessed presentation. It could also give them more exposure to English while building their subject knowledge:

It can expand their horizons beyond the foundation or theoretical knowledge they learn in lectures. Students have experience of learning this way, and it can help with lifelong learning, one of the learning outcomes for this module. I also think using video may develop their confidence. (T, Interview 1a)

5.2.2 Developing presentation skills, sharing thinking

By sharing their video proposal with 15 other groups, peer learning would take place at the level of the whole cohort, not only at group level. This would also allow students to observe diverse approaches to presentations and the dynamics within other groups. Historically, feedback had been instructor-led, but in DGPP1 students would also benefit from peer comments:

Multiple perspectives are better than only mine. They have their own thinking, and they can also contribute a lot to their peers’ learning. I will still leave comments, but it won’t be so teacher centred. (T, Interview 1a)

In-video peer feedback could be a mechanism for students to ‘share their thinking’ about subject content. Not only would this benefit their peers, but it could also provide T with further evidence of learning. Unlike in DGPP0, where his feedback was hidden in a private email, T’s in-video comments would be publicly available to the cohort.

5.2.3 Interactivity and efficiency in hybrid teaching

In Semester 1, 2021–22, the University introduced mixed-mode synchronous or hybrid teaching. Students could once again meet in person, to build relationships with group members, exchange ideas and record proposals. The video approach also offered far greater efficiency for all members of the community. Commenting in videos, rather than commenting on them via email or a forum, would not only be more engaging, but might also save people time due to the ‘convenience’ associated with the tool:

I thought students could make better use of their time outside lectures and tutorials; they can do it anywhere, anytime. I can do it in more efficiently too. I can give all the students comments. (T, Interview 1a)

In a context where students were more likely than before to complain about additional tasks, it was important that peer feedback should be as efficient as possible. Therefore, in designing the activity, he took care to ensure that it was not viewed as a compulsory assignment, offering students a ‘bonus mark’ as an incentive for participation. Pairing groups, so Group 1 would comment on Group 2’s proposal, and vice versa, was also a purposeful decision to minimise students’ workload. It would also ensure each group received a similar amount of feedback.

5.2.4 Limited cognitive scaffolding

Recognising that students were not familiar with the tool, T created a simple how-to guide including screenshots of the platform. He also used lecture time to give students hands-on practice in annotating a video, using the tool. Other potential challenges were acknowledged but not addressed. While T accepted that students had difficulty ‘understanding how a proposal can be good, bad or just average’ and recognised the need to ‘create examples for students to follow’, such cognitive scaffolds were not developed. Rubrics were also not provided.

5.3 Cycle 1: Implementation and process reflection

Scanlon and Issroff’s (2005) Activity Theory-derived evaluation criteria were used to analyse students’ experiences of DGPP1, highlighting contradictions in the new, re-mediated system.

5.3.1 Interactivity

T posted feedback comments on each group’s video before the students commented. He explained:

I felt I could give them ideas on what to write about and help them improve. Most students are not from a science background. (T, Interview 1b)

His approach ensured each group received one instructor comment and these comments were publicly available:

I like the fact I can leave a comment in the video and all students can see. This way, the students and I can communicate with each other. (T, Interview 1b)

Student survey responses indicated expectations had been met. They welcomed opportunities the tool afforded for direct communication with both T and their peers. It ‘linked students together, by giving comments to, or receiving comments from, partner groups.’ Reviewing peers’ proposals allowed students to ‘learn how other groups work… look into different angles’ whilst developing their own proposals. Feedback was seen as constructive and developmental, helping to improve ‘specific aspects’ of ‘topic and content’:

It recorded comments from my teacher and peers that I can look back on. (Student comment, Survey 1b)

Figure 6 shows the interactions between all 16 groups. Two groups, 1 and 5, interacted particularly well, with all members authoring at least one comment. Most of the eight members of Group 1 watched six or more videos, commenting on at least two. In nine other groups, half of the members were active.

Relationship map illustrating the interactions between all groups in Semester 1, numbered 1 to 18. Groups 3 and 16 were not used. Larger circles show that more comments were received by the group, while darker colours indicate that more comments were given. Thicker lines are used to highlight where more comments were given to the target group

However, participation was low overall. Only 61 students viewed peer videos and just 42 posted peer comments. In four groups, despite some evidence of peer video viewing, no one commented; in a further two groups, just one person posted a comment. In many cases, division of labour within groups was unequal. Between the groups, students’ interactions were also unbalanced. Groups 2 and 6 received nine comments each, yet Group 17 received only one comment and Group 10 received none. Only 48 students replayed their own video to access the comments that their peers and T had posted.

T reflected that his approach to feedback might have inhibited students from commenting. On reading his authoritative analysis of their proposal, it is possible that some students felt they had nothing more to add, or that their ideas might conflict with what T, the subject matter expert, had posted. This can be seen as a secondary contradiction between division of labour and object. By leading the feedback process with the desire to guide or support students, T inadvertently prevented some of them from taking on an active role in working towards the object of giving and receiving peer feedback. It can also be interpreted as a tertiary contradiction. In using the tool, T may have been influenced by the historical system, DGPP0, where feedback was provided by the instructor. Students may also have been influenced by instructor-led feedback approaches that they had previously experienced, believing it was the instructor’s responsibility, not theirs, to evaluate students’ work.

T also reflected that the lack of cognitive scaffolding in DGPP1 had made it challenging for many students to engage in peer feedback, particularly since they were in their first year of university study, lacked feedback literacy and were from non-science backgrounds. Not having access to cognitive scaffolds meant that there was a secondary contradiction between subject and object. Many students were unable to complete the activity without this additional tool.

5.3.2 Efficiency

Student survey responses revealed that their use of the tool had helped achieve them achieve their desired outcomes without wasting time and effort. For example, viewing peer videos enabled them to collect ideas from other groups, while peer comments enabled them to improve their presentation skills:

I can get a better understanding on how to improve my presentation and make it easier for the audience to follow. I might be able to deliver a better presentation. (Student comment, Survey 1b)

The students valued the flexibility of asynchronous online learning, which allowed them to ‘view videos anytime’ and ‘take comments into consideration’. Yet, it was the time-stamp functionality in particular that made learning ‘efficient and convenient’ for both feedback providers and recipients. When used, it enabled students to post about specific aspects while viewing. Feedback was therefore perceived to be more contextualised and simpler for recipients to refer to. Time-stamped comments allowed them to quickly ‘locate where to improve,’ and made feedback ‘more meaningful.’

The 42 students who engaged in peer feedback posted an average of 64.2 words and 1.69 comments, viewing peer videos an average of 7.93 times and watching an average of 6.14 min of peer video. Active students were specific in their comments. Within 71 comments, students included 262 specific feedback units, achieving an average specificity score of 3.40 across all posts and a mean specificity rating of 2.85 per post. Feedback was balanced between the five specificity categories with a mean balance score of 0.72. Given that students’ desired outcomes were to develop their proposals and presentation skills by analysing and commenting on peers’ videos, this represents efficient use of the tool. The tool was also efficient in helping students access and understand any feedback received. The 48 students who were motivated to read peers’ comments spent on average 0.72 min doing so, viewing their own video an average of 2.75 times. Given the high specificity of the comments, this represented efficient use of students’ time.

However, students’ use of time-stamping was less efficient. Rather than writing multiple short contextualised comments on specific parts of the proposal, students tended to write single comments covering more than one aspect, as shown in Fig. 7. On this aspect, T reflected that the format of his feedback might have been unhelpful, as it consisted of rather long, overall comments, not a series of time-stamped contextualised posts. Students may have chosen to follow this example. This was a secondary contradiction between the tool, designed for short time-stamped comments, and cultural rules that might have encouraged students to follow the instructor’s lead.

5.3.3 Serendipity

Several students expressed surprise at how the time-stamp function facilitated meaningful interaction and engagement with peers, T and subject content. This made them more willing to participate in a process which had traditionally been instructor-led. Several students exceeded the minimum requirement, not only commenting on the group they had been assigned, but also viewing multiple proposals before selecting a second or even third group to comment on. T was pleased to discover the extent of their peer learning, reflection and critical thinking:

Some students made very constructive comments and raised unexpected questions. They really learned something. (T, Interview 1b)

Even where two groups had investigated the same topic, the activity provided unexpected learning opportunities: analysing a peer group’s video enabled students to consider it from an alternative perspective. Students were also ready to provide social-affective support to peers using the tool, motivating less confident students to take part:

Some are shy to speak up in person. Video comments helped introverted students to develop confidence in public speaking. (T, Interview 1b)

5.3.4 Cost

T reflected that the relatively low number of marks associated with the activity might have discouraged some students from taking part:

I intended it to be a compulsory task, but the students knew it didn’t count for many marks. That might be why they neglected it. (T, Interview 1b)

For this group, the ‘cost’ of participation was that they would have less time to complete other assessments. Other students who chose not to participate described the experience as likely to cause embarrassment, implying a social cost.

In both cases there was a secondary contradiction between the object and rules: those around grading, and cultural rules governing interactions between students in this context.

5.3.5 Failure

Students who did participate were frequently critical of the tool. Not all found the time-stamp function intuitive. Many did not realise they needed to pause the video to comment in a specific location, making their posts appear decontextualised:

I often forgot to pause, so the feedback I posted wasn’t on the time stamp that I wanted to talk about. This might lead to confusion for the owner of the video. (Student comment, Survey 1b)

Students reported that the mobile version of the tool had bugs and ‘the screen was not clear enough, especially the comment function.’ Others found that unreliable home internet connections, another primary contradiction, disrupted their ability to engage ‘anytime, anywhere.’

Furthermore, while T had hoped to increase engagement through using an alternative to email and discussion forums, commenting in the video platform functioned in much the same way, with text-based, asynchronous communication. The tool also lacked a notification feature, further impeding student–student interaction. This primary contradiction can explain why only 29 of 42 active commenters read the comments on their own video and none of the groups replied to a single comment. The tool had been selected precisely because of its value in supporting peer discussion, yet these issues undermined this primary purpose.

5.4 Cycle 2: Modelling and examination

Process reflection from Cycle 1 at the end of Semester 1 was the stimulus for modelling and examination in Cycle 2 at the start of Semester 2. In the first interview, T constructed and explored a more culturally advanced model, DGPP2 (Fig. 8), to address the contradictions that had been inherent in DGPP1 in Semester 1.

5.4.1 Cognitive scaffolding and instructor facilitation

This time, before students used the annotation tool, T would provide additional cognitive support: explicit guidance on writing specific comments. In a change to the division of labour, T would not post feedback until at least one student in the partner group had commented; the process would be ‘instructor-facilitated’ rather than instructor-led. To increase the number of comments, students would comment on two videos. Grading remained unchanged, however, with a ‘bonus mark’ for participation.

5.4.2 Expanded expectations

The pre-task survey revealed that the additional guidance on feedback practices had expanded students’ expectations of how the tool could help them achieve desired outcomes. By facilitating exchanges of ideas and specific comments, it could scaffold reflection. This would allow students both to ‘understand weaknesses, to improve their speaking skills’ and ‘build self-confidence through positive feedback.’ Peer commenting could also enable them to learn from how others had developed their proposal.

5.4.3 Return to remote learning

Students reported that the return to fully online teaching in Semester 2 would make it more difficult to meet in person, establish relationships and develop a coherent proposal:

My groupmates are not very active… I think one of the obstacles is that we need to do the project online instead of face to face. (Student comments, Survey 2a)

5.5 Cycle 2: Implementation and process reflection

DGPP2 was applied in practice in Semester 2. The same framework was used to analyse participants’ experiences of its implementation, allowing any new contradictions to be identified.

5.5.1 Interactivity

In contrast to Semester 1, T gave students time to comment first without intervening. In a departure from DGPP2, he then decided not to comment at all. Sixty students participated, an increase on the previous semester. Eight groups interacted well, with most or all members commenting on at least one proposal. In these groups, the students tended to view several videos before selecting a second group to comment on. In five other groups, around half of the members were active. In only one group did no one comment. The outcome was that group interactions were more balanced than Semester 1, with each group receiving at least three comments. This is shown in Fig. 9. Unlike in Semester 1, when several students viewed peer videos without commenting, most students did comment after viewing.

Student expectations of peer interaction were more fully met. Survey responses reported that online interactions had generated ‘other ideas and perspectives’ that they could ‘incorporate into their final presentation.’ Students felt their peers had watched their video in detail.

However, it is still noteworthy that 34 students did not interact using the tool. This can be explained by three contradictions in DGPP2. Firstly, as T noted, it is possible that not having opportunities to interact in person before using the tool affected the sense of community within the cohort, impeding interactivity. Secondly, it is likely that the absence of instructor feedback meant that some students’ expectations about the division of responsibilities were not met: there was a secondary contradiction between community and division of labour. As T reflected, active facilitation, validation and encouragement could have motivated more students to interact. Lastly, despite T’s clear guidance around feedback provision, students did not have access to a rubric with standardised criteria to scaffold their feedback. This generated a secondary contradiction between tools and subject.

5.5.2 Efficiency

The 60 students who engaged in peer commenting posted an average of 1.68 comments and 78.6 words. In doing so, they viewed peer videos an average of 6.03 times, and watched an average of 5.46 min of video. Active students were also highly specific in commenting. In 101 comments, they included 388 specific feedback units, achieving an average specificity score of 3.08 across all posts, a mean specificity rating of 2.65 per post, and a balance between specificity categories (0.80). This represents efficient use of the tool, albeit marginally less so than in Semester 1. It may be that when a larger proportion of students used the tool, it included more students who were less skilled in giving feedback.

The tool was efficient in helping students access and interpret feedback they received. Over an average of 0.66 min, with an average of 1.77 views, 47 students read their peers’ comments. Given the specificity of the comments, this represents efficient use of students’ time, as in Semester 1. It is noteworthy, however, that only half of the cohort viewed feedback they had received. If their desired outcome had been to use the feedback to develop their proposal and presentation skills, not accessing it at all seems inefficient. Table 1 compares students’ use of the tool between Semesters 1 and 2.

In contrast to Semester 1, most students made effective use of time-stamping, and more comments were contextualised and focused on single aspects. This reflects the increased attention paid to the time-stamp function in the additional guidance T had provided. Students’ survey responses emphasised the efficiency of the tool in enabling them to use the feedback received. Time-stamped comments directed them to ‘exactly what had to be changed’, and were ‘more targeted’ in revealing shortcomings:

Those evaluations can point out deficiencies, such as fluency or pronunciation problems. I can understand weaknesses through multiple evaluations and focus on improving them. (Student comment, Survey 2b)

Students’ responses also yielded insights into how the tool made it more efficient to learn through peer commenting on others’ proposals:

The operation is easy. I can pause and continue while writing comments. (Student comment, Survey 2b)

It made students feel confident that their comments would be read and understood:

Peers know which part we are commenting on by the time shown. (Student comment, Survey 2b)

These processes enabled them to realise desired outcomes:

[It is] helpful to compare our own project proposal with others, as we can know our pros and cons about the project. (Student comment, Survey 2b)

5.5.3 Serendipity

Not commenting on students’ videos allowed T to see what students could accomplish alone. More confident students posted early, enabling peers to follow their examples of good feedback practice. This was an unexpected benefit of this approach to facilitation.

5.5.4 Cost

No feelings of embarrassment were reported by students. It is possible that not knowing others in the cohort, due to the return to online learning, reduced some of the ‘social’ cost students had experienced in Semester 1. However, as T noted, the use of the ‘bonus mark’ may have signalled to some students that the peer feedback process was less important than other assessments and did not merit their full participation. The contradiction from Semester 1 between rules and object remained unresolved, affecting students’ motivation. In contrast, the students who did participate were felt to have been motivated by wider learning objectives and personal growth rather than the attainment of a small grade.

5.5.5 Failure

Students highlighted an additional shortcoming in the design of the tool which inhibited peer discussion: it lacked features such ‘likes’ and emojis that could have allowed them to appreciate aspects of their peers’ work. Such features might have increased participation through removing the ‘costs’ of engagement to students who lacked confidence.

5.6 Consolidation and generalisation

Exploring the contradictions in DGPP2 makes it possible to plan how the outcomes of the intervention may be consolidated into future peer feedback practices in the module, provided that the contradictions (numbered 1–4 in Fig. 10) are resolved. It is then possible to explore how video-annotated peer feedback could be generalised to other activity systems.

Representation of key contradictions inherent in DGPP2: 1 Primary contradictions within the tool: Shortcomings of the tool; 2 Secondary contradiction between community and division of labour: Lack of active facilitation; 3. Secondary contradiction between tools and subject: Lack of rubric to guide peer feedback; 4. Secondary contradiction between rules and object: Participation ‘bonus mark’ did not increase student motivation

5.6.1 Overcome the shortcomings of the tool to promote peer dialogue

The tool has recently been updated to allow users to choose to be notified when another user comments on their video. However, other primary contradictions within the tool (1), such as its reliance on text-based communication, have not been resolved. Students must be given guidance to overcome this through the use of social language in online posts or, if future contexts permit, through in-person discussion. This informal peer dialogue can provide social-affective support, essential for promoting task-focused discussion in contexts where the students are from diverse backgrounds or have not previously met.

5.6.2 Use active facilitation

T accepted the need to manage students’ video-annotated peer feedback more actively, yet without dominating the discussion by providing extensive feedback comments. This could involve writing time-stamped questions or comments to stimulate initial discussion among the less confident groups; acknowledging and developing ideas in more active groups; and contacting inactive groups to remind all members to comment. This approach could resolve the secondary contradiction between community and division of labour (2). However, it would require skill on the part of the instructor, as it would have to be tailored to the needs of each group. Expectations of peer feedback would need to be communicated and managed. Such skills would need to be cultivated by educational developers within the institution.

5.6.3 Develop a rubric and give students practice in applying it

Though he did not provide one in Semester 2, T accepted the importance of providing students with a rubric in order to resolve the secondary contradiction between tools and subject (3). Additionally, students must be given opportunities to practise applying the standardised criteria by assessing exemplar proposals using the annotation tool. Where possible, future activity systems might involve students in developing rubrics, using an assessment for learning approach. In this way, rubrics could be an expression of the students’ own voice, making the activity more motivating.

5.6.4 Use wider learning objectives, not grades, to enhance motivation

Findings from Semesters 1 and 2 led T to note that students could be more motivated to engage in peer feedback if it were viewed as part of the project as a whole, not as a separate activity carrying a ‘bonus mark’. This should underscore the importance of evaluating other proposals and receiving peer comments in developing group ideas. It should also resolve the contradiction between rules and object (4). Where possible, peer feedback must be presented as a formative process, linked to wider learning objectives on the programme.

6 Discussion

6.1 Research questions

-

RQ 1. How does the design and implementation of a video-annotated peer feedback activity to develop students’ presentation skills re-mediate a culturally entrenched activity system?

In this study, T and two cohorts of students used the video annotation tool over two successive cycles of expansive learning to expand the object of their activity system. Traditionally, students had worked in groups to write a project proposal, the purpose of which was to develop their knowledge of climate change. Students had not found the task motivating and complained of ‘free riders’, which T was unable to monitor. It was also challenging for students to interact and exchange ideas online. Under newer versions of the system, re-mediated by the tool, students engaged in peer feedback to develop video proposals, through which they enhanced their presentation skills, self-confidence and, in the most culturally advanced system, feedback literacy and evaluative judgement. Creating video proposals and engaging in annotated peer feedback enabled T to monitor participation. Particularly in Cycle 2, where the T did not post feedback, students experienced the process as interactive. It was also efficient in enabling students to compare their proposal with others, developing their understanding of the required standard, and then quickly access specific, targeted suggestions for future improvement.

-

RQ 2. What systemic contradictions may be generated in the design and implementation of the video-annotated peer feedback activity?

-

RQ 3. How might these contradictions be overcome in future versions of the activity?

Primary contradictions emerged within the tool, impeding the efficiency and interactivity of the activity system. These included the absence of notifications, causing some students not to read peer feedback, and the lack of rich media and social features, which could have reduced barriers to communication. These issues undermined the primary purpose of the tool. Notifications must be enabled and used, while students must be given guidance to overcome barriers through social language online or informal in-person peer dialogue. These social-affective supports should also enable students to overcome cultural barriers to communication online, such as perceived embarrassment.

Secondary contradictions were revealed between community the division of labour, in T’s approach to feedback provision. Providing summary feedback before students had commented, in Cycle 1, inhibited ideas-sharing. Not giving or facilitating feedback in Cycle 2 also impeded discussion, since student expectations of the division of responsibilities were not met. This can be overcome through active facilitation approaches, tailored to the needs of each group, where instructor and student responsibilities are made explicit.

There was also a secondary contradiction between rules and object: ‘bonus’ marks did not increase student motivation, and may have led some to see the activity as unimportant. To overcome this, video-annotated peer feedback must be presented to students (and experienced by them) as a formative process, linked to wider learning objectives on the programme.

Lastly, not providing a rubric to guide peer feedback created a secondary contradiction between subject and tools. This inhibited the development of feedback literacy and evaluative judgement. To overcome this, students must not only have access to rubrics, but also be given opportunities to practise applying standardised criteria by assessing exemplar proposals using the annotation tool. Where possible, students should be involved in developing rubrics, using an assessment for learning approach.

6.2 Contribution to knowledge

Our study highlights the fundamental role of the instructor in video-annotated peer feedback processes. It signposts the negative consequences of, on the one hand, an instructor-led approach in which the instructor is viewed as the ultimate judge of students’ work, and, on the other, the instructor not being present at all. In conceptualising instructor feedback as either beneficial (Ritchie, 2016; Simpson et al., 2019; Yoong et al., 2023b), detrimental (Murillo-Zamorano & Montanero, 2018) or non-essential (Leger et al., 2017), the existing literature overlooks when and why instructor feedback may be less effective in supporting peer feedback and what may happen in specific contexts if it is not provided. It suggests that students benefit from having space to comment, but that interactive, efficient and specific video-annotated peer feedback also requires active instructor facilitation. Rather than presenting themselves as the most important feedback source, instructors ought to focus their time and effort on scaffolding and facilitating peer feedback, fostering feedback literacy and evaluative judgement. This will be critical in settings such this first-year undergraduate module, where students may lack these skills and have limited subject knowledge.

Our study also provides further evidence to support the argument that grading students on their participation is unlikely to increase motivation. It also highlights the need to build social-affective support into task design and implementation. Students who took part in each cycle appeared to be motivated by the opportunity to use ideas gained from viewing peer videos, as well as peer feedback, to improve their presentation skills (Krause et al., 2022) and therefore enhance their performance in the summative task (Simpson et al., 2019; Toland et al., 2016). In contrast to Nikolic et al.’s (2018) findings, grading appeared to have a negative impact on the large numbers of students who did not participate. In addition, it is likely that the lack of active instructor facilitation, and not being able to meet in person, particularly in Cycle 2, negatively affected student motivation because they were unable to overcome feelings of anxiety and stress associated with video-based peer feedback (Lewis et al., 2020; Smallheer et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2021). Student motivation, then, is not simply determined by the use or non-use of grading, by the presence or absence of the instructor, or by the use of in-person versus online learning. Rather, it requires peer feedback to be seen as a formative process linked to summative assessment, actively facilitated by the instructor, with opportunities for students to provide social-affective support.

Lastly, our study highlights why particular forms of cognitive scaffolding can be more or less effective in specific sociocultural contexts, as well as the potential consequences of not providing scaffolding. It also underscores the importance of scaffolding in promoting efficient and interactive peer commenting using the tool. Results from both learning cycles suggest that not using a rubric negatively impacted students’ evaluative judgement (Ritchie, 2016) and feedback specificity (Anderson et al., 2012). The additional guidance given in Cycle 2 around effective feedback contributed to greater interactivity, as reported elsewhere (Colasante, 2011; and Ellis et al. (2015). However, our findings suggest that greater efficiency and specificity in student feedback may require more active forms of scaffolding, such as training or practice in applying rubrics to exemplars (Hsia et al., 2016; Murillo-Zamorano & Montanero, 2018; Nagel & Engeness, 2021; Yoong et al., 2023a, b; Zheng et al., 2021). Whatever the affordances of video annotation tools, video-based feedback processes must be designed and implemented with students’ needs, and therefore appropriate cognitive scaffolding, in mind if students are to take full advantage of them.

7 Conclusion

This paper has investigated how Hong Kong students’ use of a video annotation tool re-mediated an established approach to developing a project proposal in an undergraduate general education module. In a field dominated by experimental and quasiexperimental studies, it used an Activity Theory-derived research design and framework to analyse two cycles of the design and implementation of a video-annotated peer feedback activity. This made it possible to examine how students’ experience of using the tool was shaped by complex, interrelated sociocultural factors. It also suggested how the emerging activity system could be consolidated and generalised if systemic contradictions are overcome by practitioners in practice.

It contributes to several bodies of knowledge. First, it underscores the importance of the instructor’s role in peer feedback: not feedback giver or passive observer, but active facilitator and scaffolder, cultivating internal feedback (Nicol, 2019) and evaluative judgement (Ajjawi et al., 2018; Tai et al., 2017). Second, it highlights the need for peer feedback to be designed and implemented as a formative process, connected to summative assessment tasks and programme learning objectives, rather than an additional graded assessment. Social-affective support is also critical to motivation and must be built into design and implementation. Third, it signposts the centrality of cognitive scaffolding in promoting efficient and interactive peer commenting using the tool. Particularly when working with students with low levels of feedback literacy or evaluative judgement, this must move beyond written guidance to incorporate opportunities for students to practise applying rubrics to exemplars using the tool.

One potential limitation of our research design is that whilst participants were engaged in questioning and analysing the historical activity systems, implementing the new models, and reflecting on the process, their agency in modelling and examining new systems was somewhat limited. As interventionist researchers, we had considerable influence over the activity design in each cycle. The instructor might have benefited from working through each expansive learning action in turn and constructing his own representations of existing and planned systems. Having these activity system diagrams and the time to think through them might have generated richer discussions. Instead, we created the diagrams after each interview had taken place. Furthermore, students’ involvement was restricted to open-ended survey responses. While these did enable us to better understand and analyse their historical challenges, expectations of the re-mediated activity system and experiences of video-annotated peer feedback, the students had no role in constructing the new system: this had been decided on before their survey responses had been collected. Student focus groups or even workshops, using a Change Laboratory approach (Bligh & Flood, 2015), with opportunities for real-time contemplation and collaboration, might have yielded a far richer understanding of their role as subjects in the activity system. This could then have been used to inform the design and implementation of the re-mediated models in each cycle, thus enhancing the findings of the research.

It would also be valuable to study the design and implementation of video-annotated peer feedback in other contexts, including different levels of study, other knowledge domains or other types of communicative skill.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Admiraal, W. (2014). Meaningful learning from practice: Web-based video in professional preparation programmes in university. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 23(4), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2013.813403

Ajjawi, R., Tai, J., Dawson, P., & Boud, D. (2018). Conceptualising evaluative judgement for sustainable assessment in higher education. In Developing Evaluative Judgement in Higher Education (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 7–19). Routledge.

Anderson, K., Kennedy-Clark, S., & Galstaun, V. (2012). Using Video Feedback and Annotations to Develop ICT Competency in Pre-Service Teacher Education. Australian Association for Research in Education (NJ1).

Baran, E., AlZoubi, D., & Bahng, E. J. (2023). Using video enhanced mobile observation for peer-feedback in teacher education. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 39(2), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2023.2180116

Bligh, B., & Flood, M. (2015). The change laboratory in higher education: Research-intervention using activity theory. In Theory and method in higher education research (pp. 141–168). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Colasante, M. (2011). Using video annotation to reflect on and evaluate physical education pre-service teaching practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.983

Davids, L. K., Pembridge, J. J., & Allam, Y. S. (2015). Video-annotated peer review (VAPR): Considerations for development and implementation. In 2015 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition (pp. 26–1701).

Ellis, J., McFadden, J., Anwar, T., & Roehrig, G. (2015). Investigating the social interactions of beginning teachers using a video annotation tool. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 15(3), 404–421.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. Perspectives on Activity Theory, 19(38), 19–30.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive Learning at Work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by expanding. Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educational Research Review, 5(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

Evi-Colombo, A., Cattaneo, A., & Bétrancourt, M. (2020). Technical and pedagogical affordances of video annotation: A literature review. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 29(3), 193–226.

Fadde, P., & Sullivan, P. (2013). Using interactive video to develop pre-service teachers’ class-room awareness. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 13(2), 156–174.

Fukkink, R. G., Trienekens, N., & Kramer, L. J. C. (2011). Video Feedback in Education and Training: Putting Learning in the Picture. Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 45–63.

Gatrell, D. (2021). Learning to serve: Designing and implementing a video-annotated peer feedback activity to re-mediate students’ development of interpersonal communication skills in a service-learning subject. Unpublished manuscript.

Gatrell, D. (2022). Challenges and opportunities: Videoconferencing, innovation and development. Studies in Technology Enhanced Learning, 2(2).

Hammoud, M. M., Morgan, H. K., Edwards, M. E., Lyon, J. A., & White, C. (2012). Is video review of patient encounters an effective tool for medical student learning? A review of the literature. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 3, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S20219

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2016). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Herrmann-Werner, A., Loda, T., Erschens, R., Schneider, P., Junne, F., Gilligan, C., Teufel, M., Zipfel, S., & Keifenheim, K. E. (2019). Face yourself! Learning progress and shame in different approaches of video feedback: A comparative study. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 1–8.

Hsia, L. H., Huang, I., & Hwang, G. J. (2016). Effects of different online peer-feedback approaches on students’ performance skills, motivation and self-efficacy in a dance course. Computers & Education, 96, 55–71.

Hulsman, R. L., & van der Vloodt, J. (2015). Self-evaluation and peer-feedback of medical students’ communication skills using a web-based video annotation system. Exploring content and specificity. Patient Educ Couns, 98(3), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.007

Hunukumbure, A. D., Smith, S. F., & Das, S. (2017). Holistic feedback approach with video and peer discussion under teacher supervision. BMC Medical Education, 17, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1017-x

Krause, F., Ziebolz, D., Rockenbauch, K., Haak, R., & Schmalz, G. (2022). A video-and feedback-based approach to teaching communication skills in undergraduate clinical dental education: The student perspective. European Journal of Dental Education, 26(1), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12682

Lai, C., Chen, L., Yen, Y., & Lin, K. (2020). Impact of video annotation on undergraduate nursing students’ communication performance and commenting behaviour during an online peer-assessment activity. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(2), 71–88.

Leger, L. A., Glass, K., Katsiampa, P., Liu, S., & Sirichand, K. (2017). What if best practice is too expensive? Feedback on oral presentations and efficient use of resources. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1109054

Leung, K. C., & Shek, M. P. (2021). Adoption of video annotation tool in enhancing students’ reflective ability level and communication competence. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 14(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2021.1879187

Lewis, P., Hunt, L., Ramjan, L. M., Daly, M., O’Reilly, R., & Salamonson, Y. (2020). Factors contributing to undergraduate nursing students’ satisfaction with a video assessment of clinical skills. Nurse Education Today, 84, 104244.

Li, L. Y., & Huang, W. L. (2023). Effects of Undergraduate Student Reviewers’ Ability on Comments Provided, Reviewing Behavior, and Performance in an Online Video Peer Assessment Activity. Educational Technology & Society, 26(2), 76–93.

Murillo-Zamorano, L. R., & Montanero, M. (2018). Oral presentations in higher education: A comparison of the impact of peer and teacher feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(1), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1303032

Nagel, I., & Engeness, I. (2021). Peer Feedback with Video Annotation to Promote Student Teachers’ Reflections. Acta Didactica Norden, 15(3), 24. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.8192

Näykki, P., Laitinen-Väänänen, S., & Burns, E. (2022). Student Teachers’ Video-Assisted Collaborative Reflections of Socio-Emotional Experiences During Teaching Practicum. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p. 846567). Frontiers Media SA.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

Nicol, D. (2019). Reconceptualising feedback as an internal not an external process. Italian Journal of Educational Research, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.7346/SIRD-1S2019-P71

Nikolic, S., Stirling, D., & Ros, M. (2018). Formative assessment to develop oral communication competency using YouTube: Self- and peer assessment in engineering. European Journal of Engineering Education, 43(4), 538–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2017.1298569

Pless, A., Hari, R., Brem, B., Woermamm, U., & Schnabel, K. P. (2021). Using self and peer video annotations of simulated patient encounters in communication training to facilitate the re-flection of communication skills: an implementation study. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 38(3).

Rich, P. J., & Hannafin, M. (2009). Video annotation tools: Technologies to scaffold, structure, and transform teacher reflection. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 52–67.