Abstract

This study aims to reveal pre-service teachers’ experience in virtual museum design that they can use in social studies teaching, and their opinions on virtual museum applications. In line with this purpose, phenomenology design was used as one of the qualitative research approaches. Selected by the criterion sampling method, the study sample consisted of a total of 15 pre-service social studies teachers (9 female, 6 male) who were studying in year 4 at the Department of Social Studies Education of a State University in the 2021/22 academic year. During the 9-week virtual museum design process, virtual museums on “epidemics, women’s rights, population, environmental problems, climate, human rights, and migration” were designed through the Artsteps application. The study was executed in a dynamic manner in co-operation and interaction with pre-service teachers based on the principles of design, implementation and evaluation. A semi-structured interview form was used as a data collection tool to determine the opinions of pre-service teachers about virtual museums and the use of virtual museums in social studies teaching. The data was analysed by content analysis. The results revealed that the virtual museum design process positively affected the views of pre-service teachers and that virtual museums are very effective and applicable tools in social studies teaching. This study suggests that virtual museums be used in social studies courses since they offer rich content to achieve meaningful learning in social studies courses owing to easy accessibility, and that future studies focus on examining the effects of popularizing virtual museums designed with gamification and guided content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Out-of-school learning refers to a multidimensional process in which structured learning activities are performed outside a classroom to study in various environments, such as the community and nature (Bunting, 2006) for learning experience that supports and enriches the knowledge and skills students acquire at school and provide opportunities for practical application. Such experience supports students at all levels of education (Yeşilbursa, 2008) with respect to development and learning in cognitive, affective, and kinaesthetic areas (Priest, 1986). By developing the skills of putting theoretical knowledge into practice, in addition to questioning, exploring, experiencing, and researching, out-of-school learning environments (Ainsworth & Eaton, 2010) play a critical role in enabling students to develop intrinsic motivation (Andersson & Johansson, 2013), desirable attitude towards the course (Sturm & Bogner, 2010), academic achievement (Nadelson & Jordan, 2012), and permanent learning (Price, 2017). Along with creativity and self-control skills (Daş et al., 2021), it encourages students to cooperate, thereby contributing to the development of social skills (Orion et al., 1997). The Turkish Ministry of National Education (MoNE, 2018) recommends making use of out-of-school learning experience in the education process in its 2023 education vision with the following statement: “It will be ensured that out-of-school learning environments such as natural, historical and cultural places, science and art centres and museums are used more effectively in line with the intended learning outcomes contained in the curricula”. The idea is that since museums are continuous and permanent institutions in the service of society with their functions of collection, documentation (archiving), conservation (maintenance—repair), exhibition and education [(ICOM International Council of Museums, 2015)], they offer students a unique opportunity for discovery in science, visual arts, mathematics, and social studies courses (McLeod & Kilpatrick, 2001). The main purpose of museums today is not only to collect, display and preserve historical artefacts, but also to use them for learning purposes (Andre et al., 2017). In fact, contemporary museology considers education as its primary function (Çıldır & Karadeniz, 2017). In other words, by updating their educational objectives within the scope of their mission and collections (Grenier, 2010), museums are capable of providing students with knowledge, skills, and experience (Hooper-Greenhill, 2000; Ören, 2023). In this way, museum learning can be achieved by enabling visitors to understand the value of historical artefacts, learn about science, history and art (Andre et al., 2017) and respect different cultures (Karadeniz, 2015). Besides facilitating permanent learning by increasing students’ motivation (Kaschak, 2014; Marcus, 2008; Tran, 2006), museums also offer opportunities for concretization (Harun & Salamuddin, 2010), reflection, questioning and application to life (Hein, 2004). They also support the development of aesthetic and creative thinking (Şişman, 2019), and help students understand historical events and citizenship issues more easily (Kaschak, 2014). The fact that museums are such powerful learning environments is due to their capacity to enable people to establish emotional connections with the past, cultural elements, and their knowledge (Taylor & Neill, 2008). In short, museums are very effective in structuring the future and transferring knowledge and experiences to future generations. Apart from the fact that museums are such effective learning environments, economic reasons, lack of time (Egüz & Kesten, 2012; Siedel & Hudson, 1999), difficulty in controlling the process, security concerns (Yaşar-Çetin, 2021), lack of motivation (Çiçek & Saraç, 2017), decreasing interest and low participation in museums by the younger generation (Crowley et al., 2014), issues regarding parental consent, accident risks (Aladağ et al., 2014), lack of museums suitable for the content of every single course (Şentürk et al., 2020), difficulty of visits in the absence of guidance (Mayer, 2004), bureaucratic obstacles (Çengelci, 2013), besides the limitations in the planning and execution processes of trips can be counted as the reasons why the majority of teachers are unable to visit museums and historical sites (Şimşek & Kaymakçı, 2015) or tend to avoid this responsibility (İnce & Akcanca, 2021). While the real museum experience will always remain important, new technologies make it possible for students to use virtual museum data to have a more comprehensive museum experience without going to the museum (Meirkhanovna et al., 2022). From this standpoint, virtual museums can be a good alternative when real museum visits are not possible for teaching activities (Tatlı et al., 2023).

Museums not only provide access to general information about museums, but also offer web-based services with direct access to their assets, digital collections and online exhibitions (Walsh et al., 2020). One of these web-based services is virtual museums, an online learning platform. Virtual museums, also called online, digital or electronic museums (Schweibenz, 2004), are in a way an extension of the traditional museum, but is composed of multidimensional works and hypermedia based on a network technology (Foo, 2008). Defined in 1947 by Andre Malraux as a concept of a museum without space and spatial boundaries, virtual museums (Styliani et al., 2009) contain information about a particular museum, exhibit its collections online, aim to explore the assets in the museum, provide detailed information about the collections, establish constant communication, and offer worldwide access services (Schweibenz, 2004). Though not new as a concept, virtual museums have been in high demand, especially during the pandemic (COVID-19), when museums were closed and physical access became limited (Aristeidou et al., 2022; Aytekin & Aktaş, 2023; Bohlmeijer, 2024; Cassidy et al., 2024), contributing to cultural experiences in the digital environment (Meirkhanovna et al., 2022), in addition to preserving and distributing cultural content and ensuring cultural interaction (Barbieri et al., 2017). As a matter of fact, transferring cultural heritage to learning environments using technology has become a necessity of our age (Caballero & Aguilera, 2019). Virtual museums which are a communication channel for the transmission of cultural heritage (Taranova, 2020) are actually promising environments for spreading this heritage beyond physical exhibition spaces (Sylaiou et al., 2009). The design and development of museums’ information resources, websites and various digital initiatives has become a key to the success of museums in the digital environment (Barszcz et al., 2023). In other words, virtual museums may also be considered as a digital asset, which enhances and complements or enriches the museum through interactivity, personalization, user experience, and content richness (Sylaiou et al., 2018). However, despite such advantages, research also shows that virtual museums have some disadvantages. One of the disadvantages is based on the idea that visiting museums virtually fail to create the same effect and perception as they do while visiting them physically (Kayapa, 2010). In fact, virtual museums offer a virtual reality, but do not offer the opportunity to interact with objects one-to-one, as they cannot stimulate the senses of touch, feeling and smelling. Besides this, virtual museums are also limited environments in terms of social interaction (Tranta et al., 2021). Moreover, virtual museum experience requires Internet connection, technology access, and technology usage skills. Consequently, technology-related drawbacks such as Internet connection problems, technical errors, and people’s lack of skills in the use of technology can pose a problem in virtual museums (Rautiainen, 2024; Ünal et al., 2022). Furthermore, problems such as complex orientation without maps, poor movement control, inadequate guidance, lack of information points with start and end points also represent the weaknesses of virtual museums (Komarac & Ozretić Došen, 2023). Even when these problems are considered in a deeper sense, the technological aspects of virtual museums still seem to pose challenges not only for the institutions themselves, but also for the participants. This is due to the pricing of experiences, the management of legal rights for the digitisation of artworks, as well as the high costs of virtual reality equipment that may be required for immersive experiences, which can refer to something as simple as a lack of interactivity in the technology components (Dasgupta et al., 2021; Simone et al., 2021). Digitisation and digitalisation have modified the museum’s relationship with its visitors, making it more complex and increasing the expectations of museum visitors due to innovative uses of digitalisation (Fanea-Ivanovici & Pană, 2020). Despite growing expectations of museum visitors for interactive and digital presentations, this leads the museum sector to initiate larger-scale adjustments that could further accelerate the integration of technology into what is being presented and require new skills for the workforce (Dibitonto et al., 2020). This also results in high costs of adapting modern technologies to allow digital visits (Amorim & Teixeira, 2021). In addition, technological failures may occur in the process of converting physical catalogues to digital media, resulting in loss of information, and therefore, some information remains to be not digitalized (Stauffer, 2012). Although it is possible to digitize textual data through high-quality digital photographs, handwritten documents contain errors due to the inability of technology to decipher some handwriting (Sporleder, 2010). The fact that the stores offered by real museums are not available in virtual museums is also considered as a disadvantage in terms of the proper representation of contemporary museum services (Komarac et al., 2019). It can also be considered that this outcome reported in the literature will contribute to the virtual museum design from a different angle.

Virtual museums cannot replace the real experience, though they can greatly enhance our understanding of artefacts (Li & Huang, 2022). Despite some disadvantages of virtual museums, the quality of the activity and the educational outcomes are closely related to how the teacher plans and carries out the process (Yılmaz et al., 2018). It should be noted that real museum experience and virtual museum visit experience are different and both have strengths and weaknesses (Schweibenz, 2019).

Virtual museum offers an effective teaching environment with its three-dimensional and interactive technology (Kim et al., 2006). In fact, by offering an alternative approach to the traditional classroom model, it appears to significantly differentiate the learning environment through their features (Schweibenz, 2004). Table 1 provides the features that distinguish virtual museum-supported learning environments from traditional classroom ones.

As can be seen in Table 1, the opportunities offered by virtual museums to learning environments indeed comply with the constructivist paradigm that shapes and directs the structures of today’s education systems. It is an interactive learning platform that goes far beyond a simple visit (Zhao, 2012). It is also an immersive environment that turns passive visitors into active explorers (Li & Huang, 2022). This environment provides visitors with autonomy (Li, 2022), freedom to be active participants in creating their own virtual tours and paths (Styliani et al., 2009), and interactive learning (Li & Huang, 2022) by increasing students’ learning capacity (Ambusaidi & Al-Rabaani, 2019). Due to their great impact on the transmission of social values (Antonaci et al., 2013) and to offering authentic experiences (Lo Turco et al., 2019), virtual museums have become an important material of the lifelong learning process (Kabapınar, 2014). Since they prepare students for the real museum experience (Kersten et al., 2017), saving methods and costs, and are exciting in the implementation process (Styliani et al., 2009), are also an effective way to develop students’ digital literacy (İlhan et al., 2021) and technological skills (Gılıç, 2020). In addition to all these explanations, virtual museum visits increase the likelihood of a real museum visit (Katz & Halpern, 2015) and facilitate its evaluation (Kersten et al., 2017). Since museums exist to communicate and provide collective access to information, having virtual settings is potentially one of the most effective ways to achieve this goal (Carvajal et al., 2020). Based on this, educational practices in many countries of the world have been integrated with virtual museums (Uslu, 2008). Figure 1 illustrates this integration in different areas.

Research shows that virtual museums, which can be included in teaching in different disciplines ranging from social sciences to science, have gained an important place in the field of education (Fig. 1). Given the framework of the use of virtual museums in the field of education, it appears that virtual museums have been included in the teaching process at different learning levels in K-12 classes [primary school (Çelik & Güllühan, 2022; Fokides & Sfakianou, 2017; Topkan & Erol, 2022), secondary school (Küçükgençay & Peker, 2023), high school (Kaya & Okumuş, 2018)] and university (Castro et al., 2021; Hu & Hwang, 2024). In this teaching process, virtual museums were found to be effective on different variables such as academic achievement (Adıyaman-Kalemkaş, 2023; Ermatita et al., 2023), motivation (Castro et al., 2021), history awareness (Topkan & Erol, 2022), attracting attention (Vera et al., 2024), higher-order thinking skills (Hu & Hwang, 2024), class participation (Yow, 2022), scientific process skills (Adıyaman-Kalemkaş, 2023), as well as sensitivity to cultural heritage (Besoain et al., 2022; Ismaeel & Al-Abdullatif, 2016), twenty-first century skills (Antonaci et al., 2013), and permanent learning (Hu & Hwang, 2024). Virtual museums have been proved to provide significant effects on different variables in different fields, among which social studies course has a very important place (Ambusaidi & Al-Rabaani, 2019). Reasons such as the fact that the social studies course is considered as a monotonous, boring (Yılmaz & Şeker, 2011) and rote-learning-based course (Heafner, 2004) and that there are many abstract concepts (Ünal & Er, 2017) make it inevitable to instruct with alternative practices. Many researchers who are aware of this necessity state that since virtual museums offer fun, interesting solutions for social studies lessons (Çınar et al., 2021) besides economical and practical ones (Zantua, 2017), increase motivation (Kayabaşı, 2005), concretize abstract knowledge (Saraç, 2017), develop the skills of perceiving time and chronology, change and continuity and space, which are all particular to social studies course (İlhan et al., 2021; Tserklevych et al., 2021), and help gain values (Sevi & Er-Türküresin, 2023), it is important to make use of virtual museums in this regard (Tuncel & Dolanbay, 2016). In fact, there is a close relationship between virtual museums and the social studies course (Çınar et al., 2021). However, it appears that reasons such as insufficient knowledge of social studies teachers regarding virtual museums (Aktaş, 2017) and their lack of training cause teachers to fail to use virtual museums efficiently (Egüz & Kesten, 2012). In order to benefit from virtual museum applications, teachers are expected to have the necessary knowledge and skills to create these environments (Çoban & Göktaş, 2013). Considering modern technology and educational understanding, it is important that pre-service teachers are trained during their academic studies and actively encouraged to use virtual museums as a tool while teaching in a social studies course in order to meet this expectation. This will ensure that their students will benefit from this learning tool in the best way when they start their profession. In this respect, the power of the virtual museum application lies in the teachers’ ability to customize it to address students’ learning goals and interests (Aristeidou et al., 2023). Therefore, it is important to increase visitor engagement by designing intriguing learning experiences (Hassan & Ramkissoon, 2017). The fact that designing in virtual environments is a long and demanding task (Çoban & Göktaş, 2013) proves that this aspect of the study is also regarded valuable. However, research shows that the majority of the studies on virtual museums are for evaluation purposes (Avcı & Öner, 2015; Çengelci, 2013), while studies based on virtual museum design experience (İşlek & Danju, 2019) are very limited in number. Since the effective use of information technologies to make creative activities will positively affect the quality of education, it is of great importance that teachers are trained in this field and researchers encouraged. The aim of this study is to eliminate the gap in the literature in this regard and to reveal the pre-service teachers’ experience of the virtual museum design that they can use in social studies teaching and their opinions on virtual museum applications. In line with this purpose, answers to the following questions were sought:

-

What are the meanings that pre-service social studies teachers attribute to the concept of museum and virtual museum?

-

What are their opinions about the importance of virtual museums in social studies teaching?

-

What are their opinions about the interdisciplinary aspect of virtual museums?

-

What are their opinions on popularizing the virtual museums?

2 Method

2.1 Research design

Conducted with a phenomenological qualitative research design, this study aimed to reveal the pre-service teachers’ experience of the virtual museum design process in order to make use of it in social studies teaching, along with their perspectives on the virtual museum application. The phenomenological design is used with the aim of understanding the experiences of the participants regarding a certain phenomenon and the meanings they attribute to it (Van Manen, 2016). Phenomenology is based on the idea that there are multiple ways of interpreting the same experience and that the meaning of the experience for each participant is “what constitutes reality” (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014). Although all qualitative research approaches have this orientation, the philosophy behind phenomenology emphasises experience itself and how experiencing something transforms into consciousness (Merriam, 2013). This emphasis is also stated by many researchers who produce philosophical arguments on phenomenological research (Creswell, 2016).

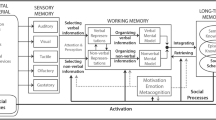

Given the principles and application processes of phenomenology in this study, instructional technologies in social studies education have been described as a sleeping giant for more than twenty years (Martorella, 1997). Despite the fact that social studies education has great potential for instructional technologies, many social studies educators still seem to be hesitant about how and why they should incorporate instructional technologies into their classrooms (Kayaalp & Meral, 2023). They rather tend to make use of any instructional technology into the classroom only if they understand why and how to use it (Doolittle & Hicks, 2003). When considered in terms of the nature of virtual museums, which have an important place in social studies education, virtual museums can be regarded as a digital tool that develops, complements or enriches the museum through interaction, personalisation, user experience, and content richness (Sylaiou et al., 2018). In order to understand why and how virtual museums as a digital tool can provide a learning experience, and likewise, why and how they should be integrated in social studies education, the experiences of many people need to be revealed in detail. Due to this need, the phenomenological approach was selected in the study with the aim of revealing the experiences of a number of pre-service teachers regarding the use of virtual museums in social studies courses in detail. Referring to the common narrative of many people’s experiences about a phenomenon or concept (Creswell, 2016), the main purpose of phenomenology is to reduce individual experiences regarding that phenomenon to a general explanation in order to be able to understand its true nature (Van Manen, 2016, p. 177). For that reason, a phenomenological design was employed in the present study aiming to explore and understand the nature of virtual museums through the experiences of pre-service teachers. Figure 2 below illustrates the methodological process of this study conducted through the phenomenological design.

2.2 Study Sample

Phenomenological research approach requires a heterogeneous study group ranging from 5 to 25 people who directly experience the phenomenon itself (Polkinghorne, 1989). Based on this necessity, the study sample consists of 15 pre-service social studies teachers (9 female, 6 male) studying in their 4th year of college at the Department of Social Studies Education of a state university in the 2021/22 academic year. In the design of the sample, utmost care was taken to create a study sample that would reflect the relevant phenomenon (virtual museum experience) in real terms.

For the purposes of the present study, criterion sampling method was used to determine the study group. In this method, cases / situations that meet the predetermined criteria are included in the sample (Gezer, 2021). The criterion in this study is that the pre-service teachers has already taken art and museum education course or museum education course in addition to the contemporary world problems course in the undergraduate programme of social studies teaching. Table 2 below presents the relevant information about the study sample.

2.3 Virtual museum design process

This study aimed to reveal the pre-service teachers’ direct experience of a virtual museum application to engage in social studies teaching or to enable them to be an active part of the design process and, accordingly, to demonstrate their perspectives on the virtual museum application. Table 3 presents the virtual museum design process in which pre-service social studies teachers were directly involved.

In order to draw attention to epidemics, the participants integrated the historical adventure of such diseases from the past to the present to the virtual museum environment. Figure 3 presents the designed virtual museum content.

As one of the main objectives of the social studies course, the understanding of sustainable development is another topic addressed by pre-service teachers in the present study. Those who wanted to draw attention to the environmental dimension of sustainable development goals presented the contemporary environmental problems in the virtual museum environment, thereby carrying the issue of change in the environment from past to present to the virtual museum environment. Figure 4 below illustrates some of the virtual museum content designed in this study.

In addition to the history of epidemic diseases and environmental problems, the pre-service teachers also involved different contemporary topics in the virtual museum environment. Figure 5 below shows some examples of virtual museums designed by pre-service teachers for varying subject matters.

As can be seen in Fig. 5, the participants designed a virtual museum environment that would best reflect the given topics, and incorporated the visuals they had previously created as well as some explanatory content texts for the visuals, and interesting video examples. The location map would enable the visitors to easily visit the virtual museum.

2.4 Data collection

Apart from the presence of different data sources (observation, documents, pictures, etc.) in the data collection process of phenomenological research, what is generally prioritised is the interview with individuals who directly experience the phenomenon that is the source of the research subject (virtual museum experience in this study) (Creswell, 2016). The reason is that the nature of phenomenological research necessitates obtaining the underlying cause, basic structure or truth of experience (Merriam, 2013). From this standpoint, this study involved a semi-structured interview form as a data collection tool so as to determine the views/experiences of pre-service teachers on the use of virtual museums in the social studies course, and the museum education literature was examined in depth while preparing this form. Based on this theoretical structure, a draft questionnaire was developed and the opinions of a museum education expert- an associate professor at a state university-, who has extensive knowledge and experience in the field of museum education in Türkiye, were obtained about the draft questionnaire. In line with the feedback, necessary arrangements were made on the draft form, which was then finalized and interviews conducted accordingly with 15 pre-service teachers who completed the implementation process of the virtual museum design. Before the interview, the participants were informed that the data obtained from them would only be used in a scientific research and that their identity information would not be revealed (coded as P1, P2, …….. P15). The interview questions used in the study are presented in Table 4 below.

The interviews were conducted using a voice recorder. In qualitative research, it is very important to conduct in-depth interviews in order to reveal the thoughts, perceptions and knowledge of the participants in detail and accurately (Patton, 2014). The same questions were asked to each pre-service teacher in the face-to-face interviews, lasting for approximately 20–30 min.

2.5 Data analysis

This study employed a content analysis method to analyse the qualitative data obtained as a result of the interviews conducted to determine the experiences of pre-service teachers regarding the use of virtual museums in the social studies course. Prior to the content analysis process, the interviews with the pre-service teachers were transcribed and transferred to a Microsoft word file. The views expressed by the pre-service teachers about the virtual museum experience were read many times by the researchers. After the virtual museum experiences of the pre-service teachers were fully understood, the data analysis process was initiated. Data analysis is defined as the process of transferring the meaning of the data or giving meaning to the data (Merriam, 2013). To achieve this, a number of ways are followed. Although different methods have been proposed by different researchers, the data analysis methods of phenomenological research have been involved in this study. In fact, the nature of phenomenological research is based on a data analysis which follows a systematic process that goes from narrow units of analysis to broader units and then describes what and how individuals experience (Moustakas, 1994). It is therefore important to separate the data, present the data and transform the data into a meaningful whole. Taking into account the nature of phenomenological method, the six process steps proposed by Miles and Huberman (2016) were used for the analysis of the data obtained from the views of pre-service teachers. Figure 6 below presents the steps.

In accordance with the nature of phenomenological method, the pre-service teachers’ virtual museum experiences were examined comprehensively and their personal views towards virtual museums were included (Formulation of codes, review of codes, definitions of codes). The naming of the codes was followed by the control coding stage, and the reliability coefficient (Reliability = number of agreement/ (total number of agreement + number of disagreement) was calculated. The reliability coefficient, which is generally recommended to be 90% (Miles & Huberman, 2016), was measured as 96% for this study. In the data analysis, coding time was arranged by paying attention to analyse the data without waiting for the next data. Then, the scope of the analysis of virtual museums was extended to include the reflection of virtual museums on the mental images of pre-service teachers, as well as the place of virtual museums in the social studies course, the interdisciplinary structure of virtual museums, the methods of popularizing the virtual museums and the stakeholders (categories) who can put the methods into practice. In the final stage, what the pre-service teachers experienced and how they did it was gathered around a common theme (virtual museum). As a result, an inductive strategy (Merriam, 2013, p.167) was adopted in the data analysis process (Fig. 7). Depending on the code-category-theme trilogy, the data were transformed into a meaningful whole by expanding from a small unit of analysis to a larger one. Figure 7 illustrates a chart regarding the systematic process followed in data analysis (The complete analysis process is included in the Results section).

2.6 Validity and reliability

The credibility of scientific research depends on two basic criteria (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2011). One of these criteria is validity, which is defined as measuring one characteristic accurately without confusing it with another characteristic (Büyüköztürk et al., 2018), while the other is reliability, which is explained as conducting the same research at different times and reaching similar results (Kaleli-Yılmaz, 2019). Each researcher is expected to apply the data collection tools for validity and reliability tests in order to report them (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2011). The validity and reliability principles followed in this study are presented in Table 5.

2.7 The role of researchers

The researchers were directly involved in all stages of this study (planning, virtual museum design process, data collection and analysis, and reporting), which aims to explain the place of virtual museums in social studies teaching through the experiences of pre-service teachers. They had already been involved as researchers in an important project (TUBITAK-1001) on the use of museums in the social studies course and had experience in virtual museums and museum education by participating in various museum trainings. Such experience has been the source of many publications contributing to the field of museum and virtual museum education besides being effective in structuring the design and implementation process of this study. Since the researchers have been conducting the Contemporary World Problems course for a long time, they have a comprehensive knowledge about the subject contents that form the background of virtual museums. Such accumulation of knowledge led to the execution of the virtual museum applications on a platform where it is appropriate for the purpose and acceptable in terms of scientific knowledge.

2.8 Ethical statement

For the purposes of this study, an ethics committee certificate was obtained from the Educational Sciences Unit of the Ethics Committee of Social and Human Sciences Head Ethics Committee at Atatürk University, with the committee name: “My Museum: Pre-service Social Studies Teachers’ Experience in Designing a Virtual Museum”, with the decision number 15, dated 03.02.2022.

3 Results

This section first demonstrates the meanings that pre-service social studies teachers attributed to the concepts of museum and virtual museum, and then the place of the concept of virtual museum in social studies teaching and its reflections on learning outcomes. Finally, the importance of interdisciplinary approach in virtual museum design and the methods of including different stakeholders in the virtual museum will be discussed from the perspective of pre-service social studies teachers.

3.1 Results regarding the meanings attributed by pre-service teachers to the concepts of museum and virtual museum

The results regarding the meanings attributed to the concept of museum by pre-service social studies teachers are presented in Fig. 8.

The most common meanings attributed to the concept of museum by the pre-service social studies teachers are as follows: history (f = 10), travel-observation (f = 6), cultural transfer (f = 6), concretization (f = 6), historical artefacts (f = 5), active learning (f = 5), learning by doing (f = 5), cultural heritage (f = 5), archaeology (f = 4), art (f = 4), historical consciousness (f = 4), exhibitions and collections (f = 4) curiosity (f = 3), and the act of feeling (f = 3). However, they associated the museum less with the concepts of geography (f = 2), photographs-pictures (f = 2), interaction (f = 2), permanent and effective learning (f = 2), historical places (f = 2), civilization (f = 2), historical empathy (f = 2), architecture (f = 1), archive (f = 1), fun learning (f = 1), museum cards (f = 1), responsibility (f = 1), ethnography (f = 1), out-of-school learning (f = 1).

The participants not only attributed many different meanings to the concept of museum, but they also reflected these multiple perspectives to the concept of virtual museum. Figure 9 below illustrates the meanings attributed by the participants to the concept of virtual museum.

The majority of participants (f = 12) appeared to integrate the concept of virtual museum with the concept of technology. They also associated it with saving time and money (f = 6), distance education (f = 5), digital environment (f = 4), easy accessibility (f = 4), virtual reality (f = 4), interactive learning (f = 4), creativity (f = 4), information network (f = 4), innovation (f = 3), culture (f = 3), globalization (f = 3), contemporary education (f = 3), visuality (f = 2), individual learning (f = 2), digital archive (f = 2), imagination (f = 2), innovation (f = 1), virtual tours (f = 1), active learning (f = 1), virtual visitors (f = 1), and digital competence (f = 1).

3.2 Results regarding the importance of virtual museums in social studies teaching

Figure 10 below shows the results regarding the reflections of virtual museums on learning outcomes in social studies teaching.

As shown in Fig. 10, the participants support both cognitive and affective learning outcomes of virtual museums in social studies teaching. When considered through the direct statements of pre-service teachers, some of the effects mentioned by P6 are as follows: “Visiting the virtual museum gives the feeling of visiting a real museum. Thanks to the virtual museum, students will start to discover new learning possibilities, which will both increase their interest in the lesson and appeal to their visual and auditory intelligence and encourage them to learn more effectively. They will be able to feel as if they are experiencing the events in person and will have the chance to feel as if they have been to and seen that period”, in a way to emphasize the importance of engaging virtual museums in social studies course as a teaching tool. Pointing out that verbal and abstract subjects are predominant in the social studies course: P2 said, “Virtual museums are effective in concretizing the subject learned. In addition, since digital, vibrant and colourful environments attract students, it makes them more eager to learn”. P5, who brought up an important feature of virtual museums, said, “In virtual museums, it is aimed to bring the museum to the classroom environment in a virtual environment. In this way, it provides an opportunity for students to learn by seeing and hearing in the social studies course.” Discussing this feature of virtual museums, P3 said, “When critical phenomena, such as wars and natural disasters, do not only remain on paper, they influence learning positively as students feel them with their senses”, to exemplify the benefits of virtual museums. P9 emphasized a different aspect of virtual museums and said, “Virtual museums teach information to students in a more entertaining, curiosity-inducing, and non-boring manner in a visual-oriented way”. Similarly P12 said, “For those who are bored of listening to lectures in the classroom environment, we can increase students’ interest in the lesson with virtual museums. We can provide them with more efficient and memorable information.”

Associating virtual museums with historical thinking skills, which have an important place in the nature of the social studies curriculum, P3 said, “The use of virtual museums in the social studies course is not only supportive especially in history lessons, but also enables students to establish a connection between the past and the future, to see the lives of people in the past closely, and thus to empathize with them”, stressing the importance of developing historical empathy. Integrating the skill of perceiving change and continuity, which is an important skill in social studies teaching, into the virtual museum, P10 said, “Students build a bridge between the artefacts exhibited in virtual museums and people, so that they can associate the artefacts with people’s lives. This enables them to see the change in people in time by establishing the connection between today’s lives and objects”. Pointing out that it is necessary to protect these artefacts as much as seeing them; P10 stated that virtual museum applications “make students realize that there are different cultures and that they should protect their cultural heritage. They even offer a setting that will enable students to think critically (especially) about the history learning area within the social studies course.”

Evaluating the contributions of developments in instructional technologies to learning environments through virtual museums, P5 said, “Virtual museums eliminate inequality of opportunity and offer the opportunity to experience the museum environment in the classroom. Large museums where people in villages and small towns in the remotest corners of our country do not have the opportunity to go and see are in a way brought to the visitors thanks to the virtual museum environment”, and drew attention to the most striking feature of virtual museums. P11 mentioned the same feature and said, “Not every student can go to museums due to their location. It is difficult for a student from Konya to go to a museum in Istanbul. Although it is not possible to visit and see the virtual museums in person, it is at least as effective and instructive as a museum in terms of being economical and fun when used with virtual museum glasses. The technology of finding oneself in another place with the feeling of wandering inside also emphasizes how important the social studies course is in keeping up with the age and keeping up with technology.” With this explanation, the participant focused attention both on the easy accessibility and the economic aspect of virtual museums.

3.3 Results regarding the interdisciplinary aspects of virtual museums

Figure 11 illustrates the findings obtained from the opinions of pre-service social studies teachers regarding the interdisciplinary approach in virtual museum design.

As seen in Fig. 11, the participants stated that an interdisciplinary approach should be adopted in the design of virtual museums and mentioned which disciplines could be involved. As to how an interdisciplinary context can be established in virtual museum design, P7 said, “There can be interdisciplinary cooperation in virtual museum design. When a museum is being prepared, there can be cooperation between the disciplines of history, archaeology, architecture, and art history.” P4 stated that “interdisciplinary cooperation is absolutely possible in museum or virtual museum design. A single discipline may not be sufficient to design a museum/virtual museum. However, if a collaborative environment is created by bringing different disciplines together, a very successful design is likely to emerge. For this purpose, many different disciplines such as geography, history, architecture, and photography can come together”. In order to evaluate the virtual museum design process comprehensively, P9 stated that “there can be an interdisciplinary cooperation in the design of a museum and a virtual museum. It can be incorporated with disciplines such as palaeography, music, drama, history, archaeology, ethnography, philology, technology, and design. Despite history being the strongest one, other branches of history can also be cited as examples. Philology (linguistics) can also be included”, and to explain how this will happen, the participant further said, “For example, if an ancient tablet is found, philology is used to read it. When money is found, the science of numismatics is used. If we try to read the Gokturk inscriptions, we will benefit from such disciplines too. From such examples, we can see that it is not possible to access information only with knowledge of history. The fields of science such as philology, anthropology and palaeography are very important resources for museums and virtual museums.”

3.4 Results regarding the popularization of virtual museums

The results obtained from the opinions of pre-service social studies teachers regarding the means and methods of popularizing virtual museums or involving different stakeholders in the process are presented in Fig. 12. As seen in Fig. 12, the participants offer a perspective on the process of popularizing virtual museums and the roles of different stakeholders in this process. In this context, P3 said that “virtual museum projects can be developed in cooperation with municipalities. Municipalities can be involved in virtual museums in terms of planning and data. The reason is that the aim of social studies is to raise individuals who are integrated with their environment and aware of what is going on around them. Additionally, families can be made aware with the support of the municipality. Municipalities will have a great impact on reaching students in every corner of our country”, in order to emphasize that the municipality functions as a stakeholder and the projects as a method of popularizing the museums and virtual museums. On the other hand, focusing on parents as a stakeholder to popularize the virtual museums, P11 said, “We can encourage parents to the virtual museums by providing trainings for them. However, it would be time consuming to encourage parents one by one. Therefore, they can be involved in museums or virtual museums by organizing seminars for those participating in community centres or courses.” Pointing out the importance of seeing sample virtual museums and providing information about them, P6 said, “Informative studies about virtual museums can be conducted to engage the stakeholders in education in virtual museums. Information can be disseminated to other stakeholders of education about what the virtual museum is, what it aims, and what kind of contribution it has in teaching. The multidimensionality and accessibility of the virtual museum can be highlighted. Cultural contributions can be explained. In order to achieve this, instructive virtual museum trips can be organized.” Approaching the stakeholders and methods of virtual museum design from a broad framework, P8 said, “By agreeing with non-governmental organizations, a realistic atmosphere can be created in this environment with VR glasses by adding various virtual activities to the end of the virtual museum activity about the issue that needs to be raised awareness. Parents can be made aware of these issues through these virtual glasses and virtual museums. It can also be ensured that municipalities create a high-level virtual museum and virtual education environment to instruct students by authorized persons. For example, students can be trained in a room designed to teach about natural disasters in accordance with the virtual museum they see in VR glasses. Or a special virtual museum can be prepared for parents, in liaison with non-governmental organizations, to provide training on how to educate children or young people about substance abuse, and at the end they can be trained with a simulation to measure how to act with the help of VR glasses.”

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study aimed to reveal the pre-service teachers’ experience in the virtual museum design process that they will themselves use in social studies teaching and their opinions on virtual museums. The results indicate that the participants have a broad perspective on virtual museum applications. This broad perspective is similar to those reported in the studies focusing on virtual museum applications (Aladağ et al., 2014; Çıldır & Karadeniz, 2017; Er & Yılmaz, 2020; Kamçı & Memişoğlu, 2020; Karataş et al., 2016). According to the first result obtained in this study, pre-service teachers attributed different meanings to the concepts of museum and virtual museum from different perspectives, and associated the concept of museum with “history”, “historical artefacts”, “cultural transfer”, “cultural heritage”, and “historical consciousness”. According to Sheppard (2001), museums enable students to understand the value of historical artefacts and cultural assets from the past to the present, to sustain sensitivity towards cultural heritage, and to adopt multiculturalism (as cited in Yılmaz & Şeker, 2011). Such features seem to be contained in the statements of our participants. Çıldır and Karadeniz (2017) demonstrated that pre-service preschool teachers considered the museum as an exhibition space where culture and historical artefacts are exhibited and cultural transfer is achieved. Er and Yılmaz (2020) reported that pre-service teachers addressed the concept of museum in the context of historical reality, highlighted the perception of historical space, and viewed museums as places that reflect the material, spiritual, and cultural characteristics of a society. In a similar manner, Kamçı and Memişoğlu (2020) reported that pre-service teachers explained the concept of museum with the concepts of “historical artefacts” “history”, and “culture”. It seems clear that the pre-service teachers’ statements about the concept of museum in the present study are similar to the results of different studies as they addressed the concept of virtual museum by integrating it with technology-related concepts such as “digital environment”, “distance education”, and “virtual reality”. Virtual museums as digital entities (Sylaiou et al., 2018) and their three-dimensional and interactive technology (Kim et al., 2006) also have a place in the views of pre-service teachers. Furthermore, the meaning that pre-service teachers attribute to the concept of virtual museum significantly overlaps with the expectation emphasized in the following intended learning outcome which reads, “they will acquire the ability to use technology in accessing information by comprehending the development process of science and technology and its effects on social life”, comprised in the social studies course curriculum (MoNE, 2018). In the study conducted on the views of teachers on virtual museums, Karataş et al. (2016) reported that teachers associated the relationship between virtual museums and technology with the opportunities of “exhibiting them visually on the Internet” as well as “having museums in computer environment” and “presenting museums digitally”. Aladağ et al. (2014) demonstrated that pre-service social studies teachers expressed virtual museums as a kind of “teaching material that enables students to visit museums out of reach”, “museums that provide access through the Internet”, and “museums that provide the feeling of visiting a real museum via the Internet”. In the same way, Aktaş (2017) indicated that teachers explained virtual museums as “a museum visit via a computer”, “a museum visit in the Internet environment”, “an interactive museum activity”, and “an online museum visit”. On the other hand, although the results of this study and the literature overlap on the opportunities offered by virtual museums, there are still some disadvantages as reported in the literature such as the necessity of Internet connection, technology access, technology usage skills, lack of interaction with the object in the virtual environment (Güllühan & Bekiroğlu, 2023; Ünal et al., 2022), orientation without a map, poor movement control, lack of starting and ending points, lack of information points (Komarac & Ozretić Došen, 2023). It appears that these shortcomings are not directly related to the virtual museum itself, but to either the hardware or the structure of the related studies. Naturally, drawbacks such as infrastructure problems, inadequacy of materials, and lack of technology usage skills of practitioners have led to the virtual museums not being able to fulfil their functions. Nevertheless, in many studies emphasising their various negative aspects, virtual museums are still reported to be a good alternative for teaching purposes (Gedik, 2023; İlhan & Dolmaz, 2022; Komarac & Ozretić Došen, 2023).

The second result indicates that virtual museums support both cognitive and affective learning outcomes in social studies teaching. According to pre-service teachers, virtual museums make contributions in relation to such aspects as “facilitating learning”, “being easily accessible”, “providing permanent learning”, “concretization”, and “developing higher-order thinking skills”. According to P5, the most remarkable feature provided by virtual museums is that “virtual museums eliminate inequality of opportunity and offer the opportunity to experience the museum environment in the classroom. Large museums where people in villages and small towns in the remotest corners of our country do not have the opportunity to go and see are in a way brought to the visitors thanks to the virtual museum environment”, emphasizing the easy accessibility aspect of virtual museums. Drawing attention to the predominance of verbal, abstract subjects and concepts in the social studies course, P2 emphasized concretization with the statement which reads, “Virtual museums are effective in concretizing the subject learned. Since the digital, vivid and colourful environment will attract students, it makes them more willing to learn.” Since virtual museums facilitate learning by seeing (Aladağ et al., 2014), they enable the concretization of information. According to Katz and Halpern (2015), this situation is expressed by the feeling of reality in the setting. This makes learning process easier (Shim et al., 2003), increases academic achievement (Bilen, 2023; Koca & Daşdemir, 2018), and allows permanent learning (Sungur & Bülbül, 2019). The effects of virtual museums on the mentioned learning outcomes have also been reported in different studies (Çalışkan et al., 2016; Karataş et al., 2016; Ulusoy, 2010). The participants were also of the opinion that virtual museums develop higher-order thinking skills. In this framework, İşlek & Danju (2019) emphasize that virtual museums develop higher-order thinking, and likewise, Kısa and Gazel (2016) point out that they especially develop critical thinking and creativity skills. In addition to matching with the intended learning outcomes, the participants also mentioned the contributions of virtual museums such as “establishing a connection with the past”, “developing historical empathy”, and “developing historical thinking skills”. Having associated historical thinking skills with virtual museums, P3 emphasized historical empathy skills by saying, “While the use of virtual museums in the social studies course is supportive especially in history lessons, museums also enable students to establish a connection between the past and the future, to see the lives of people in the past closely and therefore, to empathize with them”. The views of pre-service teachers on this aspect of virtual museums coincide with the statement given by National Council for the Social Studies which reads, “Historical understanding requires developing a sense of empathy with people in the past whose perspectives may be very different from today” (National Council for the Social Studies [NCSS], 2014, p.42). As another example, Aktın (2017) examined the effect of museum visits on historical thinking skills and grouped such skills as understanding the past, perceiving change and continuity, and historical empathy. Being one of the skills that should be acquired in the social studies curriculum (MoNE, 2018), empathy also includes the phenomenon of historical empathy (Meral et al., 2022). Students need to understand how the past has shaped today’s world and how the past and present are different from each other (Chapman, 2011). With its important contribution to the development of this historical understanding (Barton & Levstik, 2004), historical empathy enables students to critique and analyse historical sources and develop perspectives on experiences throughout history (Huijgen et al., 2017). In the same connection, Çınar et al. (2021) reveal that virtual museums help develop historical thinking skills. Constructed within the framework of qualitative (phenomenological) research, this study is also supported by the findings of quantitative studies on virtual museums in the literature. In an experimental study on the self-adaptive mobile concept mapping-based problem posing (CMPP) approach applied in the context of a virtual museum, Hu and Hwang (2024) have shown that students’ higher-order thinking skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving and metacognitive disposition, can be significantly improved. Asıksoy and İslek (2024) have revealed that virtual museum applications positively affect student achievement levels, and that interaction increases especially with applications containing 360° videos. Ariesta, Maftuh, and Syaodih (2024) have reported in their experimental study that the use of virtual museum environments can make a significant contribution to increasing student participation, developing awareness of cultural heritage, and strengthening students’ sense of nationalism. Similarly, Topkan and Erol (2022) found that virtual museum applications increased the history awareness of 4th grade students at primary school, and Yıldırım and Tahiroğlu (2012) stated that virtual museums had a positive effect on the attitude towards the social studies course. Ermatita et al. (2023) reported that the innovative virtual application developed for cultural education strongly influenced learning in the museum by offering the opportunity to examine museum collections. Kim et al. (2023) showed that immersion and preference increased through the realism of the head-mounted display (HMD)-based multisensory virtual museum and new multisensory experience. In addition, Demirel (2020) reported that the self-efficacy levels of pre-service teachers about guiding the museum visit process, using museums as a learning environment, planning the content of the course or the museum visit process in line with the needs of the students and teaching the courses in museums improved positively after the training. Both qualitative and quantitative results collected from the literature review indicate parallel results with this study, making it clear that virtual museums exert positive effects on both cognitive and affective learning.

Another result shows the pre-service teachers’ common opinion about adopting an interdisciplinary approach in the design of virtual museums and predicting about which ones to adopt. Regarding this, P7 said, “There can be interdisciplinary cooperation in virtual museum design. When a museum is being prepared, there could be cooperation between the disciplines of history, archaeology, architecture, art history.” As a matter of fact, the structure of the social studies course that integrates different disciplines (Deveci, 2009) has always been one of the important issues (Başcı-Namlı et al., 2021). Duplass (2011) stated that “social studies course comprises history, geography, economics, humanities, and philosophy. It is inclusive”, which is an assertion overlapping with the views of pre-service social studies teachers indicating that virtual museums should adopt an interdisciplinary approach. Regarding how the interdisciplinary structure should be, P9 said, “For example, if an ancient tablet is found, the science of philology is used to read this tablet. When money is found, the science of numismatics is used. If we try to read the Gokturk inscriptions, we will benefit from such disciplines too. From such examples, we can see that it is not possible to access information only with knowledge of history. The fields of science such as philology, anthropology and palaeography are very important resources for museums and virtual museums”, to indicate that the pre-service teachers explained the disciplines which virtual museums should be associated with in relation to the interdisciplinary and integrative structure of social studies.

Finally, the last result shows that the participants offered a perspective on the process of popularizing the virtual museums to make them more widespread and the roles of different stakeholders in this process. In this connection, P3 pointed to the necessity to involve different stakeholders and the impact of municipalities, in particular, by saying, “Virtual museum projects can be developed in cooperation with municipalities. Municipalities can be involved in virtual museums in terms of planning and data. The reason is that the aim of social studies is to raise individuals who are integrated with their environment and aware of what is going on around them. Additionally, families can be made aware with the support of the municipality. Municipalities will have a great impact on reaching students in every corner of our country.” The participants drew attention to the use of projects as a method to popularize virtual museums. Çalışkan et al. (2016) demonstrated that pre-service teachers emphasized the use of projects and homework assignments related to virtual museum learning experience. Moreover, the effects of digitalization are also included in participant views. P8 said, “For example, students can be trained in a room designed to teach about natural disasters in accordance with the virtual museum they see in VR glasses. Or a special virtual museum can be prepared for parents, in liaison with non-governmental organizations, to provide training on how to educate children or young people about substance abuse, and at the end they can be trained with a simulation to measure how to act with the help of VR glasses.” Advances in digital technologies enable the production of head-mounted display (HMD)-based digital cultural heritage virtual reality content that provides immersive experiences through audiovisual interaction in a three-dimensional virtual space (Kim et al., 2023). At the same time, museums can combine interfaces such as VR (virtual reality), AR (augmented reality), which offer multi-modal interaction (Liarokapis et al., 2004) with artificial intelligence technology (Alony et al., 2020; Choi & Kim, 2021), as well as mobile application opportunities (Charitonos et al., 2012). It could be possible to achieve positive visitor experiences through the application of gamification in the virtual museum experience, especially to draw visitors in more (Hammady et al., 2016; Markopoulos et al., 2021). Digital public exhibitions, such as those offered by Google Arts & Culture, can be used as common platforms for displaying museum collections in virtual spaces in an easily accessible way (Kamariotou et al., 2021). Thanks to these advanced technologies, it can be suggested that the potential benefits of museums will become much deeper and more interesting (Patias et al., 2008; Vera et al., 2024; Yap et al., 2024).

5 Limitation and suggestions

The limitations of this study is that the participants exhibited the virtual museum examples they had designed in a class environment consisting of their peers. In this sense, employing the designed virtual museums in a class environment consisting of younger age groups may reveal different results. The results of this study consist of the experiences and thoughts of 15 pre-service social studies teachers studying at a state university in Türkiye. It also seems to be possible to obtain further results in different study samples regarding virtual museum design. Despite this limitations, the following suggestions can be made, considering the multiple effects of virtual museums on social studies teaching and the results of this study:

-

Virtual museums were prepared by pre-service social studies teachers in this study in order to allow them to gain design experience. Future studies may focus on expanding the virtual museums designed through gamification and guided content so that their effects can be examined.

-

This study was conducted with pre-service social studies teachers in the context of current world problems within the framework of social studies education. Virtual museum designs can be made based on different courses and different subjects.

-

Further studies are needed to reveal the effects of virtual museum design more clearly. Researchers may conduct studies on different variables to be able to meet this need.

-

This study was conducted in accordance with the phenomenological design on the basis of the experiences of pre-service teachers. Further studies may be conducted with different research approaches to reveal the possible impact of virtual museums.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Ainsworth, H. L., & Eaton, S. E. (2010). Formal, non-formal and informal learning in the sciences. London: Onate Press.

Adıyaman-Kalemkaş, Z. (2023). The effect of science enhanced wıth virtual learning environments on academic achievements, scientific process skills and interests in science of students [Unpublished masters’ thesis]. Sakarya University.

Aksak, E. (2023). Fine Arts High School Museum Education course virtual museum applications activity example (An action research) [Unpublished masters’ thesis]. Erzincan Binali Yıldırım University.

Aktaş, V. (2017). The attitudes of the teachers of social studies about the use of virtual museum [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Marmara University.

Aktın, K. (2017). Development of the historical thinking skills of children with museum education in pre-school period. Mersin University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 13(2), 465–486. https://doi.org/10.17860/mersinefd.304070.

Aladağ, E., Akkaya, D., & Şensöz, G. (2014). Evaluation of using virtual museums in social studies lessons according to teacher’s view. Trakya University Journal of Social Science, 16(2), 199–217.

Albadawi, B. I. (2021). The virtual museum VM as a tool for learning science in informal environment. Education in the Knowledge Society. https://doi.org/10.14201/EKS.23984.

Alden Rivers, B., Armellini, A., Maxwell, R., Allen, S., & Durkin, C. (2015). Social innovation education: Towards a framework for learning design. Higher Education, Skills and Work based Learning, 5(4), 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL0420150026.

Al-Makhadmah, I. M. (2020). The role of virtual museum in promoting religious tourısm in Jordan. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 28(1), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.28121-468.

Alony, I., Haski-Leventhal, D., Lockstone-Binney, L., Holmes, K., & Meijs, L. C. (2020). Online volunteering at DigiVol: An innovative crowd-sourcing approach for heritage tourism artefacts preservation. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(1), 14–26.

Ambusaidi, N. A., & Al-Rabaani, A. H. (2019). The efficiency of virtual museum in development of grade eight students’ achievements and attitudes towards archaeology in Oman. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 4(4), 496–503.

Amorim, J. P., & Teixeira, L. M. L. (2021). Art in the digital during and after Covid: Aura and apparatus of online exhibitions. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 12(5), 1–8.

Andersson, C., & Johansson, P. F. (2013). Social stratification and out-of-school learning. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series a: Statistics in Society, 176(3), 679–701.

Andre, L., Durksen, T., & Volman, M. L. (2017). Museums as avenues of learning for children: A decade of research. Learning Environments Research, 20, 47–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-016-9222-9.

Antonaci, A., Ott, M., & Pozzi, F. (2013). Virtual museums, cultural heritage education and 21st century skills. Learning & Teaching with Media & Technology, 185, 1–14.

Ariesta, F. W., Maftuh, & Syaodih, E. (2024). The effectiveness of virtual tour museums on student engagement in social studies learning in elementary schools. Jurnal Ilmiah Sekolah Dasar, 8(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.23887/jisd.v8i1.67726

Aristeidou, M., Kouvara, T., Karachristos, C., Spyropoulou, N., Benavides-Lahnstein, A., Vulicevic, B., Lacapelle, A., Orphanoudakis, T., & Batsi, Z. (2022). Virtual museum tours for schools: teachers’ experiences and expectations. In I. Kallel, H. M. Kammoun, & L. Hsari (Eds.), 2022 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 201–209). Tunis, Tunisia. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON52537.2022.9766548

Aristeidou, M., Orphanoudakis, T., Kouvara, T., Karachristos, C., & Spyropoulou, N. (2023). Evaluating the usability and learning potential of a virtual museum tour application for schools. INTED2023 Proceedings, 1, 2572–2578. https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2023.0720

Asıksoy, G., & İslek, D. (2024). Evaluation of the effectiveness of museum education in virtual environment with 360° videos. Romanian Journal for Multidimensional Education/Revista Românească pentru Educaţie Multidimensională, 16(1).

Attwood, A. (2021). A study of anecdotal student response to virtual art museums in online history courses. The Northwest eLearning Journal, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.5399/osu/nwelearn.1.1.5599

Avcı, C., & Öner, G. (2015). Teaching with historic places social studies: Social studies teachers’ views and recommendations. Abant Izzet Baysal University Journal of Education Faculty, 15(USBES special issue 1), 108–133.

Aydoğdu, A. S. E., Aydoğdu, M., & Aktaş, V. (2022). Virtual museum use as an educational tool in math class. International Journal of Social Science Research, 11(1), 51–70. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ijssresearch.

Aytekin, H., & Aktaş, G. (2023). Research on virtual museums in Türkiye: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business in The Digital Age, 6(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.46238/jobda.1247086.

Aytekin, H. (2023). Virtual museums from visitors' perspectives: A research with a neuromarketing approach [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Dokuz Eylül University.

Baepler, P., Walker, J. D., & Driessen, M. (2014). It’s not about seat time: Blending, flipping, and efficiency in active learning classrooms. Computers and Education, 78(1), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.006.

Barbieri, L., Bruno, F., & Muzzupappa, M. (2017). Virtual museum system evaluation through user studies. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 26, 101–108.

Barszcz, M., Dziedzic, K., Skublewska-Paszkowska, M., & Powroznik, P. (2023). 3D scanning digital models for virtual museums. Computer Animation and Virtual Worlds, 34(3–4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cav.2154.

Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Routledge.

Başcı-Namlı, Z., Kayaalp, F., & Meral, E. (2021). “The reflection of the meanings attributed to the concept of “social studies literacy” on mind maps. Journal of Computer and Education Research, 9(18), 869–903. https://doi.org/10.18009/jcer.975421.

Besoain, F., González-Ortega, J., & Gallardo, I. (2022). An evaluation of the effects of a virtual museum on users’ attitudes towards cultural heritage. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031341.

Bilen, Ş. (2023). The effect of virtual reality based virtual museum design application on student achievement ın science education [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Necmettin Erbekan Universtiy.

Bohlmeijer, M. W. (2024). Systematic literature review on ınteraction design used for museum learning. [Unpublished bachelor thesis]. University of Twente, Holland. https://purl.utwente.nl/essays/98275

Bolden, E. C., Oestreich, T., Kenney, M. J., & Yuhnke, B. T., Jr. (2019). Location, location, location: A comparison of student experience in a lecture hall to a small classroom using similar techniques. Active Learning in Higher Education, 20(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417742018.

Buldu, F. (2023). The examination of social studies teacher candidates’ perspectives on cultural heritage and virtual museums [Unpublished masters’ thesis]. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University.

Bunting, I. (2006). The higher education landscape under apartheid. In N. Cloete, P. Maassen, R. Fehnel, T. Moja, T. Gibbon, & H. Perold (Eds.), Transformation in higher education Higher Education Dynamics. (Vol. 10). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4006-7_3.

Büyüköztürk, Ş, Kılıç Çakmak, E., Akgün, Ö. E., Karadeniz, Ş, & Demirel, F. (2018). Bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri [Scientific research methods]. Pegem Akademi.

Caballero, P. D. F., & Aguilera, F. J. G. (2019). Evaluation for QR codes in environmental museums. Global Journal of Information Technology Emerging Technologies, 9(2), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjit.v9i2.4268.

Çalışkan, E., Önal, N., & Yazıcı, K. (2016). What do social studies pre-service teachers think about virtual museums for ınstructional activities. Turkish Studies, 11(3), 689–706.

Carvajal, D. A. L., Morita, M. M., & Bilmes, G. M. (2020). Virtual museums. Captured reality and 3D modeling. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 45, 234–239.

Cassidy, A. C., Miller, A., & Cummins, A. (2024). A case study of community visual museums in the age of crisis. In K. Brown, A. Cummins, & A. S. Gonzales Rueda (Eds.), Communities and museums ın the 21th century (Shared histories and climate action) (pp. 221–244). Roudledge.

Castro, K. M. D. S. A., Amado, T. F., Bidau, C. J., & Martinez, P. A. (2021). Studying natural history far from the museum: The impact of 3D models on teaching, learning, and motivation. Journal of Biological Education, 56(5), 598–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2021.1877774.

Çelik, Ö., & Güllühan, N. Ü. (2022). Examinatıon of primary school students’ views and awareness on virtual museum tours of our cultural richness. Milli Eğitim Dergisi, 51(236), 2927–2946. https://doi.org/10.37669/milliegitim.1032552.

Çengelci, T. (2013). Social studies teachers’ views on learning outside the classroom. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 13(3), 1836–1841.

Chan, D. W. M., Lam, E. W. M., & Adabre, M. A. (2023). Assessing the effect of pedagogical transition on classroom design for tertiary education: Perspectives of teachers and students. Sustainability, 15(2), 9177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129177.

Chapman, A. (2011). Taking the perspective of the other seriously? Understanding historical argument. Educar Em Revista, 42, 95–106.

Charitonos, K., Blake, C., Scanlon, E., & Jones, A. (2012). Museum learning via social and mobile technologies: (How) can online interactions enhance the visitor experience? British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 802–819.

Choi, B., & Kim, J. (2021). Changes and challenges in museum management after the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 148.

Çiçek, Ö., & Saraç, E. (2017). Science teachers’ opinions about experience in out of school learning environments. Ahi Evran University Journal of Kırşehir Education Faculty, 18(3), 504–522.

Çıldır, Z., & Karadeniz, C. (2017). The views of prospective preschool teachers on museum and museum education. Milli Eğitim Dergisi, 46(214), 359–383.

Çınar, C., Utkugün, C., & Gazel, A. A. (2021). Student Opinions about the use of virtual museum in social studies lesson. International Journal of Social and Educational Sciences, 16, 150–170. https://doi.org/10.20860/ijoses.1017419.

Çoban, M., & Göktaş, Y. (2013). Üç boyutlu sanal dünyalarda öğretim materyalleri geliştiren tasarımcıların karşılaştıkları sorunlar. Mersin University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 9(2), 275–287.

Compagnoni, I. (2022). The effects of virtual museums on students’ positive ınterdependence in learning Italian as a foreign language. BABYLONIA, 3, 104–109.

Creswell, J. W. (2016). Nitel araştırma yöntemleri (Beş yaklaşıma göre nitel araştırma ve araştırma deseni). [Qualitative Inquiry &Research Desing Choosing among five approaches]. (Trans. Eds. M. Bütün and S. B. Demir). Siyasal Kitapevi.

Crowley, K., Pierroux, P., & Knutson, K. (2014). Informal learning in museums. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 461–478). Cambridge University.

Daş, B. E., Aslan, A., & Yadigaroğlu, E. (2021). The effects of out-of-school learnıng environments on health, development and sustainable development awareness of 4–6 years old children. Journal of Research in Informal Environments (JRINEN), 6(1), 87–124.

Dasgupta, A., Williams, S., Nelson, G., Manuel, M., Dasgupta, S., & Gračanin, D. (2021). Redefining the digital paradigm for virtual museums. In M. Rauterberg (Ed.), Culture and computing. ınteractive cultural heritage and arts. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. (Vol. 12794). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77411-0_23

De Oliveira, M. P., & Alves, L. R. G. (2022). Museus dıgıtaıs e ensıno de cıêncıas: Uma revısão da lıteratura. Investigações em Ensino de Ciências, 27(2), 197–221. https://doi.org/10.22600/1518-8795.ienci2022v27n2p197.

Demirel, İN. (2020). Self-efficacies of classroom teacher candidates towards education applications in museums. Abant İzzet Baysal University Faculty of Education Journal, 20(1), 585–604.

Deveci, H. (2009). Benefitting from culture in social studies course: Examining culture portfolios of teacher candidates. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 8(28), 1–19.

Dibitonto, M., Leszczynska, K., Cruciani, E., & Medaglia, C. M. (2020). Bringing digital transformation into museums: The Mu. SA MOOC case study. Human-Computer Interaction. In Human Values and Quality of Life: Thematic Area, HCI 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 19–24, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 22 (pp. 231–242). Springer International Publishing.

Dinger, K. (2021). Art teacher candidates analysis of the attitudes towards the use of virtual museum [Unpublished masters’ thesis]. Pamukkale University.

Donaldson, M. (2005). A case study of the effects of a virtual biology museum on middle school students' learning engagement and content knowledge (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Porland State University.

Doolittle, P. E., & Hicks, D. (2003). Constructivism as a theoretical foundation for the use of technology in social studies. Theory & Research in Social Education, 31(1), 72–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2003.10473216.

Duplass, J. A. (2011). Teaching elementary social studies: Strategies, standards and internet resources. Wadsworth.

Egüz, Ş, & Kesten, A. (2012). Teachers and students’ opinions regarding learning with museum in social studies course: Case of Samsun. Inonu University Journal of the Faculty of Education, 13(1), 81–104.

Er, H., & Yılmaz, R. (2020). The use of museums through the lens of teacher candidates in social studies. International Journal of New Approaches in Social Studies, 4(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.38015/sbyy.766481.

Eradze, M., Rodríguez-Triana, M. J., & Laanpere, M. A. (2019). Conversation between learning design and classroom observations: A systematic literature review. Education Sciences, 9(2), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020091.

Ermatita, E., Puspasari, S., & Zulkardi, Z. (2023). Improving student’s cognitive performance during the pandemic through a machine learning-based virtual museum. TEM Journal, 12(2), 948. https://doi.org/10.18421/TEM122-41U34T.

Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Pană, M. C. (2020). From culture to smart culture. How digital transformations enhance citizens’ well-being through better cultural accessibility and inclusion. IEEE Access, 8, 37988–38000.

Fatimah, S., & Ningsih, T. Z. (2023). Through virtual field trip technology ıntervention, can museums be a source of historical learning? In Unima International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities (UNICSSH 2022) (pp. 1275–1283). Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-35-0_154.

Fokides, E., & Sfakianou, M. (2017). Virtual museums in arts education. Results of a pilot project in primary school settings. Asian Research Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 3(1), 1–10.

Foo, S. (2008). Online virtual exhibitions: Concepts and design considerations. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 28(4), 22.