Abstract

The objective of this paper was to explore the impact of social support on the academic achievement of master’s students and the mediating effect of academic emotions in the impact mechanism. This paper collected data from 567 master’s students at J University and analyzed it using SPSS 26.0 and Amos 23.0. The results showed that social support significantly predicted academic achievement. Specifically, all three dimensions of social support (family support, supervisor support and institutional resource support) significantly predicted academic achievement. Positive academic emotions mediated the relationship between social support and academic achievement, with the indirect effect, while negative academic emotions had no significant effect on academic achievement. Therefore, to promote academic achievement of master's students, universities should create a supportive university environment and optimize the mode of postgraduate training and management, and constantly improve the support of supervisors. Additionally, master’s students should cultivate the self-regulation abilities to better stimulate positive academic emotions among them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The quality of graduate education has become a global issue. According to Nature Careers Graduate Survey 2022, pressure and uncertainty bring about the challenges of graduate education, and respondents’ satisfaction with their current program has declined from 71% in 2019 to 62% in 2022 (Woolston, 2022). As a researcher pointed out, “If this keeps up, we aren’t going to be able to produce enough people who are excited about tackling the world’s most difficult problems (Woolston, 2022).” Therefore, investigating the factors that influence academic achievement of graduates is an important research issue. Studies suggest that academic emotions (Dong & Yu, 2010) and social support (Bahar, 2010; Rosenfeld et al., 2000; Ye et al., 2014) are both crucial factors predicting academic achievement. However, further exploration is necessary. Firstly, there are different opinions on the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement in different studies. Ahmed et al. (2010), and Hernandez et al. (2015) contended that there was a positive correlation between perceived social support and academic achievement. Levitt et al. (1994) argued that there was a negative relationship between the two. Crawley (2014) proposed that there was no correlation between the two. Therefore, the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement needs further investigation. Secondly, although studies suggest that social support influences academic emotions (Hong, 2014) and academic emotions impact academic achievement (Dong & Yu, 2010), there is currently a lack of research exploring the relationships among perceived social support, academic emotions and academic achievement of master’s students.

In summary, although researchers have studied the relationship among perceived social support, academic emotions, and academic achievement, there is a need for further exploration of the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement. And there is still a certain gap in the research on the relationship among perceived social support, academic emotions and academic achievement of master’s students. This paper selected master’s students as subjects to investigate the influence of perceived social support on their academic achievement and the role of academic emotions in this influence path. The aim of this study is to elevate the academic achievement levels of master’s students, and enrich the relevant theoretical framework, as well as provide practical countermeasures and suggestions for improving the quality of graduate education and enhance the well-being of master’s students. Based on this, this paper attempts to address the following questions through empirical data: (1) What is the current status of perceived social support, academic emotions and academic achievement of master’s students? (2) How does perceived social support affect the academic achievement of master’s students? (3) Do academic emotions affect the academic achievement of master’s students? (4) Do academic emotions serve as a mediating variable between perceived social support and academic achievement of master’s students?

2 Literature review

2.1 Academic achievement

The academic achievement of master’s students is the sum of their learning results, learning behaviors and learning attitudes during their master’s period (Wang, 2022). Wang et al. (2011) points out that college students' academic achievement includes objective achievement and behavioral performance, to be specific, objective achievement refers to scores and ranking of college students, while behavioral performance includes academic performance, interpersonal promotion and learning dedication. This paper selected master’s students as research subjects. Master’s students engage in self-exploratory research-based learning under the guidance of their supervisors. The division of academic achievement dimensions of master’s students should highlight the characteristics of master’s study. The dimension of “interpersonal promotion” does not reflect the learning characteristics of master’s students and the goal orientation of master’s students’ training. What’s more, it is found that there is no significant relationship between interpersonal relationship and academic achievement (Wu & Wang, 2017). Thus, this paper excluded the dimension of “interpersonal promotion” from the academic achievement of master’s students. Postgraduates’ learning and scientific research ability is an important indicator to measure individual academic performance, so their academic achievement should include academic skills (Ke, 2017). To sum up, this study divides the academic achievement of master’s students into academic performance, academic dedication, academic skills and self-overall performance. Academic performance is master’s students’ performance of completion of learning tasks in learning and scientific research activities. Academic dedication is master’s students’ dedication in the process of academic research, including time and energy invested in learning and scientific research, attitude towards academic research problems, etc. Academic skills measure graduate students’ professional theoretical knowledge and academic research ability level. Self-total performance is master’s students’ course scores, scientific research output and awards.

2.2 Perceived social support and academic achievement

Social support is the social and psychological support that an individual receives or perceives in her or his environment (Lin et al., 1986). Since the 1970s, social support had emerged as a specialized research subject and professional concept within the academic realm. Caplan (1974) considered that social support not only included materials support and cognitive guidance, but also included emotional support. Cobb (1976) provided a psychological definition of social support, highlighting that it was primarily a reflection of individuals’ subjective emotions elicited by interventions from supportive others. Deutsch and House (1983) suggested that social support encompassed emotional caring or concern, material assistance, information support and interpersonal relationships related to self-evaluation. Brownell and Shumaker (1984) proposed that social support referred to the exchange of social resources among two or more individuals, with the aim of enhancing individual well-being, and the giver and the receiver could perceive this exchange. Social support includes received social support and perceived social support (Li et al., 2018a, 2018b). Previous studies have shown that perceived social support s more predictive and functional than actual social support (Li et al., 2018a, 2018b), so this study discusses the perceived social support of master’s students. Scholars divide the dimensions of social support not only based on the types of resources provided but also based on the providers of support (Gou, 2009). Many studies divide the dimensions of perceived social support of college students or master’s students according to the providers of support (Bahar, 2010; Dupont, 2015; Li et al., 2018a, 2018b). This kind of dimension division is helpful to understand the role played by different entities in the process of individual growth and development. This study also divides the dimensions of social support according to the providers of support. Family is a source of social support (Chu et al., 2019). From the perspective of individuals, social interaction first occurs in the family, and with the growth of age, individuals gradually reduce their dependence on the family and join other groups (Bahar, 2010). For college students, school is an important environment for their life, and the support provided by supervisors/teachers (Dupont et al., 2015) and institutions (Lian & Shi, 2020) have an impact on individual development. Therefore, this study divides perceived social support into three dimensions: perceived supervisor support, perceived institutional resource support and perceived family support.

Ecological Systems Theory emphasizes the influence of the environment on individual development, positing that human development is a product of interaction between individuals and their environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Ye et al., 2014). Ecological Systems Theory divided the environment into microsystem, mesosystem, and macrosystem. The microsystem represents the environment of face-to-face interactions in an individual’s daily life (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). From this theoretical perspective, the academic achievement of a master’s student is a dimension of their personal development. Families, educational institutions, and supervisors constitute essential components of the microsystem environment in a master’s student’s life. The support offered by these entities may impact individual development. Bahar (2010) pointed out that social support contributes to individual adaptation to the environment, thereby facilitating students’ academic success. Through empirical research, Rosenfeld et al. (2000) found that students with higher peer, parental, and teacher support tend to exhibit greater school satisfaction, engagement, and self-efficacy. Additionally, their academic achievement surpasses that of students lacking such support. Ye et al. (2014) also pointed out that the higher the level of perceived social support contributes to better learning outcomes. Rueger et al. (2010) have indicated that social support contributes to individuals’ psychological and academic adaptation. Specifically, for the dimension of family support, Hong and Ho (2005) demonstrated that parental-child communication and parental aspiration for children have the most direct, fundamental, and enduring impact on students’ academic achievement. In terms of teacher or supervisor support, Chen (2015) found that teachers consistently stand as a pivotal factor that influencing students’ academic achievement, factors such as teacher expectations, teaching behaviors, teaching styles, and teacher-student relationships have effects on students’ academic achievement. Dupont et al. (2015) found that supervisor support positively influences the academic achievement of master’s students. For the dimension of institutional resource support, Lian and Shi (2020) discovered that institutional support has a direct positive impact on students’ learning behavior, learning interest, and student development. Based on the above, this paper proposed the following research hypothesis.

-

H1: Perceived social support has a positive impact on the academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H1a: Perceived family support positively boosts the academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H1b: Perceived supervisor support positively boosts the academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H1c: Perceived institutional resource support positively boosts the academic achievement of master’s students.

2.3 Academic emotions and academic achievement

Pekrun et al. (2002) pioneered the concept of academic emotions, defining it as emotional experiences (such as joy, anxiety, boredom, etc.) that are directly linked to students’ learning activities. Yu and Dong (2005) provided further elaboration on Pekrun’s propositions. They argued that academic emotions are both outcome-oriented and process-oriented, encompassing not only the emotions derived from academic outcomes but also the emotions experienced during studying and testing processes. Scholars classified academic emotions into different dimensions, including two-dimensional, three-dimensional and four-dimensional theory. The two-dimensional theory categorized academic emotions into positive and negative emotions based on “valence”, which was adopted in the DES questionnaire (Dispositional Emotion Scale). The three-dimensional theory expanded upon this by introducing “neutral emotion”. Pekrun developed the four-dimensional theory by incorporating the dimension of arousal into previous research based on the two-dimensional theory. This theory further subdivided valence into positive and negative, and arousal into high arousal and low arousal. Therefore, academic emotions were classified into four types: positive high-arousal emotions, positive low-arousal emotions, negative high-arousal emotions, and negative low-arousal emotions. Yu and Dong (2005) followed Pekrun’s classification for categorizing academic emotions, with slight variations in specific dimensions. Ma (2008) also adapted her questionnaire based on the work of Pekrun et al. (2002). This general academic emotion questionnaire encompassed a total of ten emotional experiences: positive activating emotions (interest, enjoyment, hope), positive deactivating emotions (pride and relief), negative activating emotions (shame, anxiety, anger) and negative deactivating emotions (hopelessness, boredom). In empirical studies, it’s common to treat positive academic emotions as a whole and treat negative academic emotions as a whole (Liu, 2023; Liu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). This paper also categorizes academic emotions into positive and negative academic emotions.

Control-Value Theory and Affective Event Theory are both helpful to explain the influence of academic emotions on academic achievement. The Control-Value Theory postulates that negative academic emotions consume cognitive resources and impairs cognitive performance needing such resources, while positive academic emotions focus an individual’s attention on the task at hand and benefit cognitive performance, despite consuming cognitive resources (Perkrun, 2006; Zhao, 2013). Positive academic emotions facilitate self-regulation in learning, which fosters better cognitive flexibility, including enhancing the use of metacognitive strategies to adapt to learning goals, whereas negative emotions tend to prompt reliance on external regulation (Perkrun, 2006; Zhao, 2013). Affective Event Theory posits that an individual’s emotions can directly affect behavior or influence behavior through attitudes (Duan et al., 2011; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). It distinguishes between affect-driven behaviors directly propelled by emotions (such as tardiness or absenteeism due to a bad mood) and judgment-driven behavior where emotions affect work attitudes, subsequently influencing behaviors (such as cumulative negative emotional experiences leading to deteriorating job satisfaction, and overall negative job evaluations, eventually resulting in turnover) (Duan et al., 2011; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). According to Affective Event Theory, an individual’s academic emotions can directly influence behavior or gradually accumulate, impacting their evaluation and judgment of academic tasks, thereby altering learning behavior and ultimately affecting academic achievement. Dong and Yu (2010) had provided empirical evidence to demonstrate that academic emotions affected academic achievement both directly and indirectly. Drawing upon empirical research conducted by Bai (2016), it had been demonstrated that positive emotions served as a significant positive predictor of academic achievement, whereas negative emotions exerted a negative predictive effect on academic achievement. Lang et al. (2022) discovered that during the process of online learning among undergraduate students, the interaction between teachers and students could directly have a positive predictive effect on the learning engagement of undergraduate students. Furthermore, this interaction could enable autonomous motivation and positive academic emotions to exert their chain mediating role, thereby enhancing students’ level of learning engagement. Li et al., (2018a, 2018b) pointed out that negative emotions can lower an individual’s cognitive level, subsequently reducing the sensitivity of attention, thereby leading to a decline in his or her work performance. The above studies collectively indicate the existence of a correlation between academic emotions and academic achievement. Consequently, this paper proposed the following research hypothesis.

-

H2: Academic emotions have a predictive effect on academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H2a: Positive academic emotions have a significant positive effect on academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H2b: Negative academic emotions have a significant negative effect on academic achievement of master’s students.

2.4 The mediating role of academic emotions

Academic emotions may serve as a mediator between perceived social support and academic achievement. On one hand, as previously mentioned, academic emotions can influence academic achievement. On the other hand, from the perspectives of the Social Support Theory and the Control-Value Theory, perceived social support might influence academic emotions. The General Benefit Model of the social Support Theory suggests that social support can positively impact individuals by enhancing their well-being, fostering a positive psychological state (Rueger et al., 2016), thereby generating positive academic emotions and inhibiting negative academic emotions. The Control-Value Theory posits that the subjective appraisal of control over academic activities and outcomes, such as one’s belief in mastering learning content, can influence academic achievement (Perkrun, 2006; Zhao, 2013). According to the Stress-buffering Model of Social Support Theory, social support serves to alleviate stress (Rueger et al., 2016). Individuals receiving social support may underestimate the harmfulness of stressful situations, enhancing perceived coping abilities to reduce the appraisal of stress severity (Gou, 2009). Empirical studies have confirmed that perceived social support positively predicts one’s sense of control (Bao et al., 2022). Thus, based on the Stress-buffering Model of Social Support Theory and Control-Value Theory, the level of perceived social support might facilitate an increase in positive academic emotions and a decrease in negative academic emotions.

Hong (2014) found that school climate (including learning climate, peer support, and teacher support) had a positive effect on the generation of positive learning emotions and a negative effect on negative learning emotions. Empirical research by Chen (2017) also supported this viewpoint. Therefore, it could be inferred that as the perceived level of external support increases, individuals’ emotional experiences enhance, which in turn influences their behaviors. Based on the above, this paper proposed the following research hypothesis.

-

H3: Academic emotions play a mediating role in the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H3a: Positive academic emotions play a positive mediating role in the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement of master’s students.

-

H3b: Negative academic emotions play a negative mediating role in the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement of master’s students.

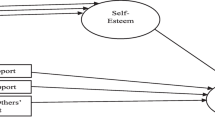

The model of research hypotheses is displayed in Fig. 1.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study is a quantitative cross-sectional study. Firstly, based on the theoretical model, this study directly selected or adapted items from existing validated scales to form the Perceived Social Support Scale, Academic Emotion Scale, and Academic Achievement Scale. The Perceived Social Support Scale drew upon relevant items designed by Jiang (2001), Overall et al. (2011), and the China College Student Survey (Lian & Shi, 2020). And the Academic Emotion Scale referenced items from scales developed by Pekrun et al. (2002), Peng (2013). The Academic Achievement Scale referenced studies conducted by Wang et al. (2011) and Ke (2017). Secondly, we conducted a presurvey to test the reliability and validity of the scales. This paper utilized SPSS 27.0 for item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and reliability tests (Qiu, 2013; Wu, 2010). Thirdly, this paper employed the three validated scales from the presurvey for the formal survey. To test for reliability and validity, this paper used SPSS 27.0 to calculate Cronbach’s α, and this paper conducted a confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 25.0 (Wu, 2013). Fourthly, this paper performed descriptive statistical and difference analysis of variables using SPSS 27.0 (Wu, 2010). Finally, this paper conducted path analysis using AMOS 25.0 (Wu, 2013) to test the hypotheses.

3.2 Research instrument

3.2.1 The perceived social support scale

Based on the literature review on social support and the conceptual definition of perceived social support, this study categorized perceived social support of postgraduate students into three dimensions: perceived family support, perceived supervisor support, and perceived institutional resource support. The measurement items for family support were mainly based on the corresponding items from the adapted questionnaire of the PSSS by Chinese scholar Jiang (2001) which included perceived economic support, perceived emotional support and other aspects, with a total of 5 items. The measurement of supervisor support referred to the scale developed by Overall et al. (2011), consisting of 6 items. Institutional resources support refers to the support provided by the university environment, including the school climate, scholarship system, research facilities, infrastructure, curriculum and so on. This paper used the China College Student Survey (CCSS) as a reference for this measurement (Lian & Shi, 2020). Combining the definition of institutional resource support, we selected six matching items from the CCSS for measuring perceived institutional resource support. This scale constituted a 5-point Likert-type scale (refer to Supplementary Material Table S1 for the scale’s content).

Before the formal survey, this paper conducted a presurvey to assess the reliability and validity of the scales. This paper distributed a total of 122 questionnaires for the presurvey and collected 112 valid questionnaires. After collecting the pre-survey data, this paper conducted initial item analysis, examining item discrimination, item-total correlation, corrected item-total correlation, and Cronbach’s alpha after item deletion (Qiu, 2013; Wu, 2010). This paper employed the extreme group method to assess item discrimination (Qiu, 2013; Wu, 2010). Through examination, all items met the aforementioned criteria (see Table S2).

Subsequently, this paper conducted an exploratory factor analysis (see Table S3). The resul ts indicated that the KMO value for the Perceived Social Support Scale exceeded 0.7, making it suitable for factor analysis (Wu, 2010). Three components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, with the cumulative explained variance over 50%, which was acceptable (Wu, 2010). Furthermore, the factor loadings for each item were all above 0.55 (see Table S3), which was acceptable (Wu, 2010). Therefore, all items met the requirements of the exploratory factor analysis, demonstrating good construction validity of the scale.

Finally, this paper used Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients to assess the reliability of the scale. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for perceived social support, perceived family support, perceived supervisor support, and perceived institutional resource support were 0.917, 0.917, 0.945, and 0.931, respectively, indicating good reliability.

In summary, this scale demonstrates good reliability and validity, so this paper used it in the formal survey.

3.2.2 The academic emotion scale

Based on Academic Emotion Questionnaire developed by Pekrun et al. (2002) and the Graduate Academic Emotions Questionnaire developed by Peng (2013), this study modified a specific academic emotions scale for master’s students. This scale included two dimensions: positive academic emotions (joy, hope, and pride…) and negative academic emotions (disgust, anger, anxiety, and shame…). The scale was a 5-point Likert-type scale and consisted of 13 items (see Supplementary Material Table S1 for the content of the scale). Higher cumulative scores on each subscale indicated a stronger intensity of the corresponding emotions experienced by the participants. Based on the data from the pre-survey, this paper preserved all the items of this scale. And the construct validity of the scale was good (see Supplementary Material Table S4, Table S5, Table S6 and Table S7 for details). Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of positive academic emotions and negative academic emotions were 0.922 and 0.884 respectively, demonstrating a good reliability. Thus, this paper used this scale in the formal survey.

3.2.3 The academic achievement scale

Based on the literature review, the academic achievement scale for master’s students included four dimensions: academic dedication, academic performance, academic skills, and overall self-performance. The items of “academic dedication” and “academic performance” referenced the study by Wang et al. (2011), the items of “academic skills” referenced the study by Ke (2017).The academic achievement scale was a 5-point Likert-type scale and consists of 18 items (see Supplementary Material Table S1 for the content of the scale). Based on the data from the pre-survey, we could preserve all the items of this scale. And the construct validity of the scale was good (see Supplementary Material Table S8 and Table S9 for details). Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of academic achievement, academic dedication, academic performance, academic skills, and overall self-performance were 0.912, 0.940, 0.913, 0.907 and 0.873 respectively, demonstrating a good reliability. Thus, this paper used the scale in the formal survey.

3.3 Population and sample

The population for this study consisted of master’s students from “Project 985” universities in China. Considering some existing research involved selecting a specific institution for random sampling (Cheng et al., 2013) as well as practical limitations, this study opted to conduct random sampling within the master's student at J University, a university of the “Project 985” located in Northeast China. All master’s students at J University resided in two dormitory buildings—one for males and one for females—where each room accommodates four or fewer students. The specific sampling method involved numbering each room in the male and female dormitories starting from 1 respectively, and utilizing random number method to select 125 rooms from each dormitory. During the preliminary survey, we randomly chose 25 rooms from the 125 male dormitory rooms and 25 rooms from the 125 female dormitory rooms. Surveyors (education master’s students who had received specialized training) visited these selected dormitories and recruited 122 volunteers. In the formal survey, surveyors visited 100 rooms from the male dormitory and 100 rooms from the female dormitory that had not been previously selected during the presurvey. We recruited 630 volunteers for the formal survey.

3.4 Data collection procedure

We conducted the presurvey in October 2022, while the formal survey was conducted in December 2022. The Institute of Higher Education of Jilin University approved this study and waived the requirement for written informed consent. We distributed questionnaires in quiet classrooms. We informed participants about the purpose, content, scope of information collected, potential benefits, and risks associated with the research. We also informed them that their participation was voluntary, and they had the right to withdraw at any time. Additionally, we informed all the participants that agreeing to complete the questionnaire was considered as providing informed consent, and we assured them that their answers would be kept confidential. Participants took approximately ten minutes to complete the questionnaires.

3.5 Data analyses

In the presurvey, we distributed 122 questionnaires and collected 112 valid ones. We analyzed the presurvey data through item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and reliability testing, following the methods suggested by Wu (2010) and Qiu (2013). After conducting these tests in the presurvey, we used the selected scales in the formal survey. For the formal survey, we distributed 630 questionnaires and collected 112 valid ones (demographic information of the formal survey sample is presented in Table 1). We conducted confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 25.0 (Wu, 2013) on the formal survey data and assessed reliability by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients using SPSS 27.0 to examine the scale’s validity and reliability. Additionally, we performed intergroup differences analysis for various variables (Wu, 2010). Subsequently, we conducted path analysis using AMOS 25.0 (Wu, 2013) to test the research hypotheses. Additionally, in the mediation analysis, this paper employed the Bootstrap method to estimate the percentage of direct and indirect effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

3.6 Ethical consideration

This paper obtained approval from The Institute of Higher Education of Jilin University, and written informed consent was waived. The reason was that the possibility of harm to participants due to the questionnaire survey was extremely low (Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University, n.d.), while the primary risk in this study was the potential breach of participant privacy, consent forms with participant signatures would elevate the risk of privacy breaches. Therefore, to ensure participant privacy, we did not gather written informed consent. Instead, we orally informed participants about pertinent aspects of informed consent.

4 Results

The collected data were processed and statistically analyzed by SPSS 26.0 and Amos 23.0. In this study, the initial step involved conducting reliability and validity testing on the scales, as well as performing descriptive statistical analysis of each variable. And then, based on the theoretical foundation and research hypothesis, a structural equation model was established. Subsequently, this paper used Amos 23.0 to conduct confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis, aiming to explore the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement of master’s students.

4.1 Reliability and validity testing

This paper tested the reliability and validity of the scales with the formal survey data. We examined the reliability analyzing the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha). For the perceived social support scale, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the whole scale was 0.918, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of perceived family support, perceived supervisor support, and perceived institutional resource support were 0.877, 0.951, and 0.904, respectively. For the academic emotion scale, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of positive academic emotions and negative academic emotions were 0.884 and 0.873, respectively. For the academic achievement scale, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the whole scale was 0.927, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients of academic dedication, academic performance, academic skills, and overall self-performance were 0.924, 0.905, 0.917, and 0.858, respectively. All of the above coefficients surpassed the recommended value of 0.70, indicating good measurement reliability.

This paper examined the composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the scales through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We used Amos 23.0 to construct a structural equation model for validating the research model. According to the CFA result (see Table 2), all the factor loadings were above 0.4, which was acceptable (Yao & Shen, 2007). All the CR values were above 0.6, indicating good composite reliability (Cai, 2021; Yin & Xu, 2017). All the AVE values were above 0.36, indicating acceptable convergent validity (Zhang & Zheng, 2021). The correlation coefficients between variables were smaller than the square root of their corresponding AVE values, indicating good discriminant validity. Overall, the scales in this study had good reliability and validity.

4.2 Difference analysis

The current status and difference analysis results among the research variables were presented in Table 3. From the table, it could be observed that social support, academic achievement, and academic emotions that master’s students perceived are above the average level. We have found significant differences in the perception of social support among different genders, degree types, and academic years. First, the female master’s students could get a higher perception of social support than the males, which could be related to the fact that women are more inclined to engage in emotional expression and communication with others (Shi et al., 2011). Second, academic-oriented master’s students could get a higher perception of social support than professional-oriented master’s students. It was widely recognized that academic master education aimed to cultivate scientific research-oriented talents, while professional master education aimed to train high-level applied talents. Therefore, society and educational institutions placed greater emphasis on academic master programs, bringing a higher perception of actual support to these students. Last, first-year students should get a higher perception of social support than second or third-year students. First-year students are still adapting to the academic demands of the master’s program. Consequently, supervisors and educational institutions tend to offer more support to first-year students compared to second or third-year students.

We have found the following results in difference analysis. First, there was a significant difference in academic achievement among master’s students across different grades. Overall, third-year students exhibited outstanding academic achievement, while compared to first-year or third-year students, second-year students had lower academic achievement, indicating their higher level of academic burnout (Cheng et al., 2008). Second, there were significant differences in positive academic emotions among different degree types and grades of master’s students. Specifically, academic-oriented master’s students exhibited higher levels of positive academic emotions compared to professional-oriented master’s students, and first-year students had higher scores in positive academic emotions compared to students in other grades. Third, there were significant differences in negative academic emotions among different disciplinary categories, with humanities and social sciences students displaying higher levels of negative academic emotions compared to STEM disciplines students. On the whole, the positive academic emotions of master’s students were relatively high. However, negative academic emotions also existed at a moderately high level.

4.3 Path analysis of the perceived social support on academic achievement among master’s students

4.3.1 Construction of structural equation model and overall fitness degree

We constructed a structural equation model to examine the path coefficients and mediating effects. Simultaneously, we calculated fit indices of the structural equation model. The fit indices of the structural equation model for the impact of perceived social support on academic achievement were as follows: χ2/df = 2.631, RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.935. The fit indices of the structural equation model for the sub-dimensions of perceived social support and academic achievement were as follows: χ2/df = 2.636, RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.935. The fit indices of the “perceived social support-positive academic emotions-academic achievement” structural equation model were as follows: χ2/df = 2.917, RMSEA = 0.058, CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.910. The fit indices of the “perceived social support-negative academic emotions-academic achievement” structural equation model were as follows: χ2/df = 2.637, RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.922, TLI = 0.917. These results demonstrated good fit indices for each structural equation model.

4.3.2 Path analysis of the effect of perceived social support on academic achievement

We examined hypothesis H1 by constructing a structural equation model for perceived social support and its dimensions in relation to academic achievement. The path analysis result of the structural equation model for the impact of perceived social support on academic achievement showed that perceived social support had a significant positive effect on academic achievement of master’s students, with the unstandardized coefficient = 0.686 and the standardized coefficient = 0.511 (S.E. = 0.103, T-value = 6.682, P < 0.001). Thus, hypothesis H1 was supported.

The path analysis result of the structural equation model for the sub-dimensions of perceived social support and academic achievement showed that perceived family support had a significant positive effect on academic achievement of master’s students, with the unstandardized coefficient = 0.089 and the standardized coefficient = 0.127 (S.E. = 0.037, T-value = 2.379, P = 0.017). Thus, hypothesis H1a was supported. Perceived supervisor support had a significant positive effect on academic achievement of master’s students, with the unstandardized coefficient = 0.105 and the standardized coefficient = 0.154 (S.E. = 0.039, T-value = 2.691, P = 0.007). Thus, hypothesis H1b was supported. Perceived institutional resource support had a significant positive effect on academic achievement of master’s students, with the unstandardized coefficient = 0.191 and the standardized coefficient = 0.267 (S.E. = 0.041, T-value = 4.610, P < 0.001). Thus, hypothesis H1c was supported.

The data revealed that the perceived institutional resource support had the greatest effect on academic achievement, while the perceived supervisor support had a relatively low effect, the effect of perceived family support was the lowest.

4.3.3 Path analysis of perceived social support and academic emotions on academic achievement

The path analysis result of the structural equation model for “Perceived Social Support—Positive Academic Emotions—Academic Achievement” showed that positive academic emotions had a significant positive effect on academic achievement, with the unstandardized coefficient = 0.310 and the standardized coefficient = 0.468 (S.E. = 0.046, T-value = 6.722, P < 0.001), supporting hypothesis H2a. In addition, the result showed that for the path of perceived social support → positive academic emotions, the unstandardized coefficient = 1.339 and the standardized coefficient = 0.646 (S.E. = 0.168, T-value = 7.988, P < 0.001). And for the path of perceived social support → academic achievement the unstandardized coefficient = 0.285 and the standardized coefficient = 0.208 (S.E. = 0.104, T-value = 2.739, P = 0.006).

The path analysis result of the structural equation model for “Perceived Social Support—Negative Academic Emotions—Academic Achievement” showed that negative academic emotions had no significant negative effect on academic achievement, with the unstandardized coefficient = -0.085 and the standardized coefficient = -0.090 (S.E. = 0.046, T-value = -1.870, P = 0.061), indicating that hypothesis H2b was not supported. In addition, the result showed that for the path of perceived social support → negative academic emotions, the unstandardized coefficient = -0.184 and the standardized coefficient = -0.129 (S.E. = 0.078, T-value = -2.351, P = 0.019). And for the path of perceived social support → academic achievement, the unstandardized coefficient = 0.670 and the standardized coefficient = 0.499 (S.E. = 0.102, T-value = 6.592, P < 0.001).

In summary, positive academic emotions had a significant positive effect on academic achievement, while negative academic emotions had no significant negative effect on academic achievement. Thus, hypothesis H2 was partially supported.

4.3.4 The mediating effect test of academic emotions

The mediating effect of academic emotions in the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement was analysed in two parts.

The first analysis was about the mediating role of positive academic emotions. The paper used the Bias-corrected nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method, testing with 2000 resamples and a 95% confidence interval. The analysis result showed that the unstandardized total effect value = 0.701 (Boot S.E. = 0.131, 95% Boot CI Lower Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.477, 95% Boot CI Upper Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.985). The unstandardized direct effect value = 0.285 (Boot S.E. = 0.140, 95% Boot CI Lower Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.043, 95% Boot CI Upper Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.596). The unstandardized indirect effect value = 0.415 (Boot S.E. = 0.100, 95% Boot CI Lower Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.256, 95% Boot CI Upper Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.648), which indicated that positive academic emotions played a mediating role in the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement, with unstandardized indirect value accounting for 59.2% of the total effect value. Therefore, hypothesis H3a was supported.

The second analysis was about the mediating role of negative academic emotions. The analysis result showed that the unstandardized total effect value = 0.685 (Boot S.E. = 0.127, 95% Boot CI Lower Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.471, 95% Boot CI Upper Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.976). The unstandardized direct effect value = 0.670 (Boot S.E. = 0.126, 95% Boot CI Lower Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.456, 95% Boot CI Upper Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.956); the unstandardized indirect effect value = 0.016 (Boot S.E. = 0.014, 95% Boot CI Lower Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = -0.003, 95% Boot CI Upper Bound in Bias-corrected percentile method = 0.055). Since the Boot CI of indirect effect included 0, hypothesis H3b was not supported. In summary, positive academic emotions played a mediating role in the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement, while negative academic emotions did not have a mediating effect. Thus, hypothesis H3 was partially supported.

5 Discussion

5.1 There are differences in perceived social support and academic emotions among different groups of master’s students

This study found that female master’s students exhibit significantly higher levels of perceived social support compared to male students, which might be related to the shaping of individual gender roles and societal expectations (Shen, 2012). Traditional gender role expectations often demand independence and assertiveness in men while requiring compassion and sensitivity in women (Shen, 2012). When an individual’s behavior aligns with societal expectations, they are likely to receive acceptance and approval. Otherwise, they might face exclusion. Therefore, the gender roles assigned to women provide them with a stronger social support network, whereas men's gender roles usually emphasize independence.

Academic master’s students exhibit significantly higher levels of perceived social support and positive academic emotions compared to professional master’s students. This difference may come from the distinct educational goals and methodologies of these two types of master’s programs. Academic master’s programs tend to nurture academic and research-oriented individuals, while professional master’s programs are more applied in nature. Therefore, academic master’s students may undergo more rigorous academic training, which might contribute to their heightened perception of social support and increased likelihood of fostering positive emotions towards learning and research.

Moreover, in the field of humanities and social sciences, negative academic emotions are notably higher compared to STEM disciplines. This discrepancy could stem from a relatively more relaxed training approach in humanities and social sciences compared to STEM fields. Humanities students might be more prone to fatigue and lethargy, potentially fostering a negative mindset over time.

Third-year master’s students demonstrate significantly higher levels of academic achievement compared to second-year students. This difference may derive from the time required for the development of academic skills, the cultivation of effective study habits, and the generation of academic achievements—all of which necessitate a longer duration. First-year master’s students exhibit significantly higher levels of perceived social support and positive academic emotions compared to second and third-year master’s students. This disparity might be due to the initial adjustment phase that first-year master’s students undergo when adapting to the academic and personal aspects of graduate school. During this period, supervisors and institutions may offer more support to this cohort.

5.2 There is a positive correlation between perceived social support and academic achievement of master’s students

Perceived social support can positively contribute to the academic achievement of master’s students, as higher levels of perceived social support are associated with higher levels of academic achievement. Ecological Systems Theory emphasizes the significant impact of the environment on individual development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), while social support is a crucial component of the environment. The General Benefit Model in Social Support Theory suggests that social support can elevate an individual’s sense of well-being and promote positive psychological states, such as increased self-worth and goal orientation (Rueger et al., 2016). Additionally, the Stress-buffering Model in Social Support Theory posits that social support can alleviate stress (Rueger et al., 2016). Both models emphasize the constructive role of social support in enhancing an individual’s psychological state. Consequently, perceived social support may positively influence learning behaviors by improving an individual’s internal psychological state. Individuals with a higher perception of social support believe that others will provide them with both emotional and tangible assistance when needed, thereby enhancing their confidence and sense of self-worth in interpersonal interactions. In the pursuit of academic achievement, master’s students strive for improved outcomes and gain recognition from others, thereby experiencing a sense of support from those around them. In summary, the perceived social support of master’s students allows individuals to experience a sense of involvement, recognition, and significance, which enhances their satisfaction with their academic achievements. Combining the results of the questionnaire survey and the findings from the relevant research, there are two main reasons why perceived social support promotes academic achievement of master’s degree students. On one hand, a higher level of perceived social support of master’s students signifies a certain level of interconnection between objective social support and subjective social support. This interplay effectively stimulates learning motivation, enhances students’ learning outcomes, and consequently increases the likelihood of achieving better academic performance. On the other hand, as the perceived social support among master’s students increases, their self-learning potential is more likely to be explored, and they exhibit higher levels of enthusiasm and engagement in their studies. Consequently, they are more prone to generating learning initiatives and adopting new learning techniques, which ultimately enhances their academic achievement.

The findings of this study are consistent with the conclusions of existing literature, indicating that perceived social support can enhance individual academic achievement (Bahar, 2010). For example, through empirical research, Rosenfeld et al. (2000) found that students with higher levels of peer support, parental support, and teacher support could get higher academic achievement compared to those without such support. Ye et al. (2014) also noted that higher levels of perceived social support were associated with better learning outcomes, highlighting the significant role of perceived social support in academic achievement. Differing from the aforementioned studies, this research focuses on the master’s student population, an area that has received comparatively less attention in similar studies, and incorporates the dimension of “supervisor support”, a unique aspect specific to the graduate education phase, within the perception of social support.

5.3 Positive academic emotion played a role in mediating the relationship between perceived social support and academic achievement

Positive academic emotions refer to the positive emotional experiences that master’s students generate in their learning and research activities. These emotions facilitate their engagement in learning, foster positive experiences, and enhance their academic pursuit, leading to higher academic achievement. Conversely, negative academic emotions can make students feel frustrated and fatigued in their learning and research activities, thereby hindering their commitment to academic tasks and resulting in lower academic achievements. According to the Control-Value Theory (Pekrun, 2006; Zhao, 2013), individual factors such as perceived control and value cognition play a pivotal role in influencing academic emotions. Additionally, environmental factors indirectly affect academic emotions by influencing individual factors. These environmental factors encompass external support. On the other hand, academic emotions can impact students’ academic achievement in the following ways. First, positive academic emotions allow individuals to focus their attention on emotional objects, thereby reducing the cognitive resources required for emotional regulation. Second, students’ learning emotions serve as triggers and regulators of their learning interest and motivation. Positive academic emotions enhance intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, while negative academic emotions, such as anxiety, diminish their learning interest and intrinsic motivation. Last, positive academic emotions facilitate students’ self-regulated learning. This is because self-regulated learning requires the use of metacognitive, meta-motivational, and other cognitive flexibility strategies to meet one’s learning goals and task requirements. According to the Affective Event Theory, the long-term accumulation of emotions may alter an individual’s attitudes and overall evaluation of work, consequently inducing behavioral changes (Duan et al., 2011; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Therefore, for master’s students, the accumulation of positive academic emotions may alter their attitudes towards the academic process and outcomes, thereby influencing their learning behaviors and subsequently affecting academic achievement.

Based on the results of the questionnaire survey and relevant research findings, the partial mediating role of positive academic emotions can be explained by the following reasons. On the one hand, as demonstrated by the empirical results mentioned earlier, perceived social support plays a positive promoting effect on academic achievement. This is because for master’s students who are sensitive to emotions and experience rapid socio-emotional development, receiving support from others is their primary unmet need. When they perceive a lack of concern from others regarding their academic endeavors or perceive themselves as being in a vulnerable position, their motivation to learn is likely to decrease. Higher levels of perceived social support enable them to experience understanding and respect from family, teachers, peers, thereby transforming their emotional satisfaction into motivation for personal development and then actively participating in their learning activities. On the other hand, the partial mediating role of academic emotions may derive from the interconnected effects of students’ psychological activities between perceived social support and academic achievement. From the perspective of social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is an individual’s belief about his/her ability to produce desired results through his/her own actions, and this factor is able to regulate human functioning through cognitive, motivational, affective, and decision-making processes, which is an important factor influencing an individual’s behavior, and self-efficacy is influenced by social support (Bandura, 2002). Therefore, perceived social support may have a positive effect on an individual’s mental activity by influencing his or her self-efficacy, thus improving students’ learning efficiency and effectively promoting personal development.

5.4 Negative academic emotions had no significant negative effect on academic achievement of master’s students

This paper found that the negative effect of negative academic emotions on academic achievement of master’s degree students was not significant at the level of P = 0.05. This is inconsistent with the findings of existing studies (Dong & Yu, 2010; Sun & Chen, 2010; Bai, 2016), which may be related to the characteristics of the subjects in this study. The existing studies mentioned above used primary and secondary school students as subjects, while the present study used adult master’s students as subjects. An empirical study showed that adolescents are less able to cope with emotional conflicts compared to adults, which may be related to the immaturity of their prefrontal regions related to emotional control (Yang et al., 2023). Therefore, master’s students may be more capable of controlling negative emotions than adolescents, and thus be better able to weaken the impact of negative emotions on academics, resulting in no significant negative impact of negative academic emotions on the academic achievement of master’s degree students.

6 Conclusion

This paper’s principal key conclusions are as follows. (1) Social support significantly predicts academic performance. Specifically, the three dimensions of perceived social support—family support, supervisor support, and institutional resource support—all significantly predict academic achievement. (2) Positive academic emotions mediate the relationship between social support and academic achievement. (3) Negative academic emotions do not significantly impact academic performance. The results of this study suggest that to enhance the quality of master’s student education and promote their well-being, collaborative efforts from families, supervisors, and institutions are essential crucial. They should provide substantial academic support to assist master’s students in achieving academic success. However, this paper has limitations. (1) It is a cross-sectional study, which cannot reveal causality among variables. (2) The sample size is limited, requiring further validation of the conclusions’ generalizability. Recommendations for future research are as follows. (1) Conducting experimental studies on the relationship between perceived social support, academic emotions, and academic achievement among master’s students to clarify causal relationships among these variables. (2) Expanding the participant pool to validate the universality of the research conclusions.

7 Recommendations for advancement

7.1 Establish a supportive institutional environment and optimize the training and management models for master’s students

First, it is necessary to optimize policies related to postgraduate education and facilitate their comprehensive development. On one hand, universities can introduce policies related to research funding, focusing on enhancing financial support for research projects undertaken by master’s students. This not only increases their motivation to engage in research activities but also provides the corresponding financial assistance. On the other hand, universities should continuously optimize the basic infrastructure for scientific research, and provide excellent hardware and software environments for postgraduate students’ learning and research, including enriching academic resources in libraries, improving research conditions, and optimizing network configurations. Additionally, compared to STEM disciplines students, those in humanities and social sciences do not have fixed research laboratories. Therefore, it is necessary to offer certain support to humanities and social sciences students concerning research facilities. Next is to optimize the curriculum for master’s students and emphasize deep learning. It is crucial to improve the quality of classroom teaching for achieving educational objectives. On one hand, it is essential to develop the curriculum system thoroughly, building it on a foundation of core knowledge structure, and organically integrating specialized knowledge, general knowledge, and applied knowledge. On the other hand, a well-designed curriculum can also promote meaningful learning, actively engaging students in the process of knowledge construction and cognitive processing. The last point is to focus on the psychological well-being of master’s students and guide them to foster positive academic emotions. Universities and teachers should actively pay attention to students’ physical and psychological development. In learning activities, they can conduct brainstorming sessions, collaborative discussions, and other activities to strengthen communication among students through collective exploration. Students should also be encouraged to use collaborative methods to solve problems, which enables them to experience more help and support from teachers and peers.

7.2 Enhance supervisors’ sense of responsibility and increase support of supervisors

The first is to optimize the mentorship system to ensure a more effective organizational management approach. The Shimen organization is a supervisor-centered academic management approach and serves as the primary learning and activity domain for master’s students. By attending Shimen meetings, students will experience a “motivational” pressure, as they present regular reports and engage in mutual communication with their peers, which allows them to learn from each other’s strengths and weaknesses through comparisons and discussions. The second is to strengthen supervisors’ support for students’ academic endeavors. For master’s students in the early stages of research, supervisors should provide effective academic guidance to reduce the period of uncertainty during their studies and help them adapt quickly to the academic and research life of postgraduate studies. For second-year master’s students, supervisors can increase the frequency of guidance to mitigate negative emotions related to academic and research challenges. For third-year master’s students, supervisors should actively address the issues students encounter in their graduation thesis and provide assistance in effectively navigating the challenges during the graduation season. The last is to improve the quality of supervisor’s education for students. Supervisors should provide master’s students with general (fundamental or universal) and targeted (personalized) academic resources to further enhance their academic proficiency. Supervisors should also proactively understand the aspects of students’ lives beyond academics, enhancing emotional interaction and showing concern for their academic anxieties, study pressures, and other related issues. By utilizing emotional interaction, supervisors can help alleviate the pressures students face during the learning process, boosting their courage to experiment and resilience, ultimately increasing their academic enthusiasm.

7.3 Cultivate the self-regulation ability of graduate students and foster the positive academic emotions

First, students should exert subjective initiative and enhance their awareness of autonomous learning management. In terms of goal management, students should establish corresponding plans based on their learning progress. By setting goals, students can plan their study time, and diligently monitor and reflect on their learning behaviors. During the interactive learning process with teachers and peers, students should critically absorb others’ viewpoints, thoroughly explore their own thoughts on issues. Meanwhile, students can construct new perspectives and concepts by integrating different viewpoints, which ultimately leads to the adaptation and assimilation of their cognitive structures. Second, students should have a clear understanding of learning adversity and establish a positive attribution model based on it. When facing learning adversity, students should engage in comprehensive and accurate attributions and apply positive psychological adjustments. Meanwhile, students should learn how to maintain a positive mindset, approach problems from different perspectives, and handle setbacks and failures in their studies with a normal attitude. Last, students should recognize the importance of academic pursuits and strive for comprehensive and harmonious development. Students should have a correct understanding of the significance of their academic pursuits, enabling them to maintain higher levels of enthusiasm and self-confidence, and thereby achieve greater learning engagement. Students should also learn to utilize the required knowledge resources and learning strategies, seeking problem-solving approaches through various channels to achieve “happy learning”.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ZR, upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmed, W., Minnaert, A., Van Der Werf, G., & Kuyper, H. (2010). Perceived social support and early adolescents’ achievement: The mediational roles of motivational beliefs and emotions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9367-7

Bahar, H. H. (2010). The effects of gender perceived social support and sociometric status on academic success. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 3801–3805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.593

Bai, H. (2016). Research on the relationship between academic emotions and aca-demic achievement of middle school students. Modern Primary and Secondary Education, 32(01), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.16165/j.cnki.22-1096/g4.2016.01.022

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00092

Bao, X., Huang, J., Li, N, Li, J., & Li, Y. (2022). The Influence of Proactive Personality on Learning Engagement: The Chain Mediating Effect of Perceived Social Support and Positive Emotions. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, (04), 508–514. https://doi.org/10.12139/j.1672-0628.2022.04.011

Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.). (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Brownell, A., & Shumaker, S. A. (1984). Social support: An introduction to a complex phenomenon. Journal of Social Issues, 40(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01104.x

Cai, H. (2021). Research on the correlation of teachers’ e-readiness and students’ learning effect: The mediation effect of learner control and academic emotions. Journal of East China Normal University (Educational Sciences), 39(07), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2021.07.003

Caplan, G. (1974). Support Systems and Community Mental Health. Behavioral Publications.

Chen, L. (2015). A review of empirical research on teacher factors which affect students’ academic achievement. Contemporary Education Sciences, 08, 30–33.

Chen, W. (2017). A study of the impact of social support and psychological capital on academic emotion of vocational college student (Master’s thesis, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China). Retrieved from https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&filename=1018086636.nh. Accessed 23 Nov 2023

Cheng, H. L., Kwan, K. L., & Sevig, T. (2013). Racial and ethnic minority college students’ stigma associated with seeking psychological help: Examining psychocultural correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031169

Cheng, T., Li, S., & Sang, K. (2008). The states of academic burnout and professional commitment and their relationship in students for master’s degree. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 1(02), 91–96.

Chu, X., Li, Y., Wang, X., Wang, P. & Lei, L. (2019). The relationship between family socioeconomic status and adolescents’ self-efficacy: The mediating role of family support and moderating role of gender. Journal of Psychological Science, (04), 891–897. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20190418

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38(5), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

Crawley, M. (2014). An analysis of the impact of social support and selected demographics on physical activity, dietary behavior and academic achievement among middle and high school students. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) Kent State University, Kent.

Deutsch, S., & House, J. S. (1983). Work stress and social support. Contemporary Sociology, 12(3), 329–329. https://doi.org/10.2307/2069001

Dong, Y., & Yu, G. (2010). Effects of adolescents’ academic emotions on their academic achievements. Journal of Psychological Science, (04), 937+945. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2010.04.024

Duan, J., Fu, Q., Tian, X., & Kong, Y. (2011). Affective events theory: contents, application and future directions. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(04), 599–607. Retrieved from https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XLXD201104017.htm

Dupont, S., Galand, B., & Nils, F. (2015). The impact of different sources of social support on academic performance: Intervening factors and mediated pathways in the case of master’s thesis. European Review of Applied Psychology, 65(5), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2015.08.003

Gou, Y. (2009). Overview of basic theoretical research on social support. Theory Research, (12), 74–75. Retrieved from https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LBYT200912034.htm

Hernandez, L., Oubrayrie-Roussel, N., & Prêteur, Y. (2015). Educational goals and motives as possible mediators in the relationship between social support and academic achievement. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 31(2), 193–207. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24763339

Hong, Q. (2014). A study of the multilateral relations among school climate, academic emotions, achievement motivation and academic achievement in junior high school students. (Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China). Retrieved from https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201402&filename=1014236433.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT. Accessed 23 Nov 2023

Hong, S., & Ho, H.-Z. (2005). Direct and Indirect Longitudinal Effects of Parental Involvement on Student Achievement: Second-Order Latent Growth Modeling Across Ethnic Groups. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.1.32

Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University. (n.d.). Informed consent of questionnaire interview of China Family Panel Studies. Retrieved from http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20200615141215123435.pdf2

Jiang, Q. (2001). Understand the social support scale. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science, 10(10), 41–43.

Ke, L. (2017). Research on construction of the evaluation system of graduate student learning outcomes evaluation system. (Master’s thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China). Retrieved from https://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10269-1017074425.htm. Accessed 23 Nov 2023

Lang, Y., Gong, S., Cao, Y., & Wu, Y. (2022). The relationship between teacher-student interaction and college students’ learning engagement in online learning: Mediation of autonomous motivation and academic emotions. Psychological Development and Education, 38(04), 530–537. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2022.04.09

Levitt, M., Guacci-Franco, N., & Levitt, J. (1994). Social support and achievement in childhood and early adolescence: A multicultural study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 15(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0193-3973(94)90013-2

Li, N., Liu, J., & Niu, L. (2018a). Effects of job burnout on safety performance——the chained mediation of negative emotion and mind wandering. Soft Science, 32(10), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2018.10.16

Li, J., Han, X., Wang, W., Sun, G., & Cheng, Z. (2018b). How social support influences university students’ academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.016

Lian, Z., & Shi, J. (2020). Research on the effect mechanism of college support on students’ learning and development: exploration based on the data from “China College Student Survey”(CCSS). Research in Educational Development, 40(23), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.14121/j.cnki.1008-3855.2020.23.003

Lin, N., Dean, A., & Walter, M. E. (Eds.). (1986). Social Support, Life Events and Depression. Academic Press.

Liu, Q., Zhang, W., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The relationship between the future orientation and learning involvement of junior high school students: chain mediation role between positive academic emotion and psychological resilience. Psychological Monthly, 18(10), 72–74+80. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2023.10.021

Liu, Z. (2023). The effect of achievement emotions on the learning engagement of students with hearing impairment: the mediating role of achievement goal orientation. Chinese Journal of Special Education, (05), 49–57. Retrieved from https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZDTJ202305006.htm

Ma, H. (2008). Development of the general academic emotion questionnaire for college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(06), 594–596+593.

Overall, N. C., Deane, K. L., & Peterson, E. R. (2011). Promoting doctoral students’ research self-efficacy: Combining academic guidance with autonomy support. Higher Edu-Cation Research & Development, 30(6), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.535508

Pekrun, R. (2006). The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP37024

Peng, Y. (2013). The graduate students’ academic emotion, and the relation among it and academic self-efficacy: The mediating effect of trait emotional intelligence. (Master’s thesis, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China). Retrieved from https://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/article/cdmd-11078-1014111106.htm

Qiu, H. (2013). Quantitative research and statistical analysis: Analysis of SPSS (PASW) data analysis examples. Chongqing University Press.

Rosenfeld, L. B., Richman, J. M., & Bowen, G. L. (2000). Social support net-works and school outcomes: The centrality of the teacher. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17, 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007535930286

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000058

Shi, B., Xiao, M., Tao, X., & Xu, J. (2011). Subjective well-being, social support and their relationship of contemporary graduate students. Academic Degrees & Graduate Education, (05), 61–66. https://doi.org/10.16750/j.adge.2011.05.013

Shen, J. (2012). College students’ perceived social support and well-being: The mediating roles of self-compassion (Master’s thesis, Suzhou University, Suzhou, China). Retrieved from https://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10285-1012388119.htm

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Sun, F., & Chen, C. (2010). The relationship between academic emotions and academic performance and its influencing factors. Journal of Psychological Science, 33(1), 204–206. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2010.01.046

Wang, S. (2022). A study on the influence of tutoring relationship on the academic achievement of full-time postgraduate students. (Master’s thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China). Retrieved from https://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10532-1023656298.htm

Wang, Y., Li, Y., & Huang, Y. (2011). The relationship between psychological capital, achievement goal orientation and academic achievement of college students. Higher Education Exploration, 06, 128–148.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective Events Theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews, Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Woolston, C. (2022). Stress and uncertainty drag down graduate students’ satisfaction. Nature, 610(7933), 805–808. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03394-0

Wu, F & Wang, X. (2017). The effect of emotional intelligence on academic achievement of college students--An empirical study based on structural equation modeling. Education Research Monthly, (01), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.16477/j.cnki.issn1674-2311.2017.01.007

Wu, M. (2010). Questionnaire statistical analysis practice –SPSS operation and application. Chongqing University Press.

Wu, M. (2013). Structural equation modeling: An advanced practice of Amos. Chongqing University Press.

Yang, M., Zhang, L., Deng, X., & Zeng, S. (2023). Age-related differences in emotional conflict control: A behavioral and ERP study. Journal of Psychological Science, (02), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20230207

Yao & Shen. (2007). The revised scale for teacher autonomy in China. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 13(04), 329–333. Retrieved from https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-YXNX200704008.htm

Ye, B., Hu, X., Yang, Q., & Hu, Z. (2014). The effect mechanism of perceived social support, coping efficacy and stressful life events on adolescents’ academic achievement. Journal of Psychological Science, 37(02), 342–348.

Yin, R., & Xu, H. (2017). Construction of online learning engagement structural model: An empirical study based on Structural Equation Model. Open Education Research, 23(04), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2017.04.010

Yu, G., & Dong, Y. (2005). Study of academic emotion and its significance for students’ development. Educational Research, 10, 39–43.

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., & Yao, B. (2023). the effect of core self-evaluation on normal university students' academic emotion: the mediating role of professional commitment. Journal of Heihe University, (03), 88–91. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-HHXY202303023.htm

Zhang, Z., & Zheng, L. (2021). Consumer community cognition, brand loyalty, and behaviour intentions within online publishing communities: An empirical study of Epubit in China. Learned Publishing, 34(2), 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1327

Zhao, S. (2013). The Research of Academic Emotions based on Control-Value Theory for College Students (Doctor’s dissertation, Zhongnan University, Changsha, China). Retrieved from http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10533-1014395779.htm. Accessed 23 Nov 2023

Funding

Research Project for Humanities and Social Sciences of Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China “‘Breaking the Five Only’: A Study on the Practice and System Optimization of Academic Evaluation Reform in Colleges and Universities” (21YJA880053).

The 2022 Jilin University's Institutional Applied Special Research Project “Research on Several Issues Regarding the High-Quality Development of Graduate Education Under the ‘Double First-Class’ background” (2022XB03).

Research Project of Jilin Provincial Social Science Fund “Research on Early Warning and Prevention System of Ideological Security Risks in Colleges and Universities in Jilin Province” (2023C79).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by Institute of Higher Education, Jilin University. Written informed consent was waived by Institute of Higher Education, Jilin University.