Abstract

Preparing the next generation of preschool teachers who can integrate and make use of ICT to capitalise on and develop young children’s digital competences remains a challenging goal for teacher education programmes (TEP). Given the current gaps in the literature, this study aims to expand and deepen our understanding of the extent to which early childhood pre-service teachers encounter ICT during their training and how they are prepared to use digital technologies in their future practices. The empirical data was generated through a focus group study with pre-service teachers and interview with their teacher educators at an institution of higher education in Sweden. The findings of the study suggest that pre-service teachers feel they have not been adequately prepared to integrate ICT into their future educational practices in preschool. Teacher educators, however, demonstrated a completely different perspective, highlighting a variety of initiatives that they were implementing to prepare the next generation of preschool teachers to use digital technologies. It will discuss why pre-service teachers, unlike teacher educators, feel they are not being adequately prepared to use digital technologies in early childhood education. The study also provides a detailed account of the varied procedures involved in preparing pre-service teachers’ digital competences and makes recommendations to teacher educators on how to enhance future preschool teachers’ TPACK.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICT) have been widely introduced as agents of change in educational practices. The ability to use and embed ICT as an integral component in educational practices is increasingly considered an important qualification for preschool teachers and preschools. However, the introduction of such technology does not seem to have transformed educational practices in preschools and schools as originally expected (Brown et al. 2016; Cuban 2018; Player-Koro 2013).

The consistent finding of a growing number of studies suggests that teachers’ beliefs, knowledge and digital skills, as well as the obstacles they perceive to the implementation of such technology, plays a key role in defining the ways teachers integrate digital technologies into early childhood education (cf. Blackwell et al. 2013; Masoumi 2015; Nikolopoulou and Gialamas 2015) and serves as the primary source for teacher’s digital skills in teacher education. It is assumed that an appropriate use of ICT in TEP will contribute to the teaching and learning process and develop pre-service teachers’ digital competences for their own professional growth. Developing the digital readiness of pre-service teachers will, it is argued, help them to promote children’s digital competences (Cuban 2001; Farmer 2016). The Swedish Higher Education Act underlines the integration of ICT as an integral part of any preschool teacher education programme (Government Bill 2009, 2017). Teacher education programmes (TEP), thus, are required to supply evidence of how well the digital competences of the next generation of preschool teachers are developed.

Many Swedish TEPs are implementing a range of initiatives to enhance pre-service teachers’ digital competences (Bakir 2015; Brown et al. 2016; Tondeur et al. 2012). Several measures, including a substantial level of investment in ICT, developing comprehensive policies and strategies to support an innovative use of ICT and developing teacher educators’ digital competences, have been put in place to extend the integration of ICT in TEP (Brevik et al. 2019; Marklund 2015). However, preparing future preschool teachers so they can integrate and make use of ICT to develop children’s digital competences remains a challenging goal for TEP (Brown et al. 2016; Instefjord and Munthe 2017; Scherer et al. 2018; Tondeur et al. 2012).

Teacher education programs, however, fall short in preparing pre-service teachers to integrate technology into their future practice. A close examination of the evidence shows that pre-service teachers have very little confidence in their ability to make use of digital technologies in their future educational practices (Brevik et al. 2019; Brown et al. 2016; Tondeur et al. 2012). Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevik (2018) and Enochsson (2010), for instance, in their study about ICT in initial teacher education, claim that pre-service teachers have very little practical experience of using digital technologies in their educational practices, although they do appear to be confident in using digital technologies for future administrative purposes. In another study, Tømte et al. (2015) found that developing pre-service teachers’ digital competences was not part of TEP in Norway. They also found that, by and large, in Norway there were no comprehensive plans to develop pre-service teachers’ digital competences. Similarly, Davis (2010) and Tondeur et al. (2012) contend that promoting pre-service teachers’ digital competences is not firmly anchored in TEP that featured in their studies. Another study, conducted in the United States by Buss et al. (2015) found that pre-service teachers were concerned with their ability to use ICT effectively in their teaching practices. The findings of Hu and Yelland (2017) further revealed that early childhood pre-service teachers had very limited opportunities to use digital technologies in ways that were based on children’s needs and interests.

Very little research, however, has focused on pre-service teachers and their educators regarding how they, as early childhood pre-service teachers, are prepared to use ICT in their future educational practices. This study, therefore, as a part of a wider project about digitalisation in higher education, examines early childhood pre-service teachers and their teacher educators’ understandings and experiences about the extent and the ways pre-service teachers are prepared to use ICT in their professional careers.

2 Theoretical and empirical foundations

2.1 Context

The preparation of early childhood education teachers in Sweden is structured as a three and a half year bachelor’s programme (210 European credits). During this programme, pre-service teachers are prepared to teach children aged 1–5 in accordance with the Swedish curriculum for preschool. The importance of using digital technologies to create a rich learning environment and stimulates children’s learning and development is underlined in the Swedish curriculum for preschool (The Swedish National Agency for Education 2018).

The Swedish preschool curriculum (2018) introduces a model called ‘educare’, where teachers are expected to integrate safe care and educational practices. This underlines the importance and necessity of developing preschool teachers’ competence in their use of ICT. Given the nature of the educare model, the integration of digital technologies into a preschool’s educational practices, however, is a complex phenomenon. There is an ongoing debate within both popular and scholarly circles about the integration process and what role early childhood TEP and teachers themselves can bring to preschool. As a result, digitalising in preschool is either considered a panacea, which can create opportunities to transform early education and prepare children for the information society (Masoumi 2015), or a threat, which can cause serious problems for young children’s development (Lindahl and Folkesson 2012).

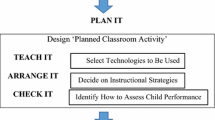

2.2 Developing pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge

The literature suggests that the integration of technology into TEP can determine the extent to which pre-service teachers go on to use ICT in their future educational practices (Blackwell et al. 2013; Kerckaert et al. 2015; Nikolopoulou and Gialamas 2015). With this in mind, TEPs ought to develop pre-service teachers’ digital competences and, as the UNESCO (2011, p. 8) suggests, enable them to design and conduct “innovative ways of using technology to enhance the learning environment, and to encourage technology literacy, knowledge deepening and knowledge creation”.

Teachers’ digital competence in a learning environment can be seen from two perspectives. These are “the teachers’ proficiency in using ICT in a professional context with good pedagogical-didactical judgement and his or her awareness of its implications for learning strategies and the digital Bildung of pupils and students” (Krumsvik 2011, p. 45). Known as ‘digital competence’, this idea includes not only teachers’ own proficiency in using digital technologies; it also refers to the extent to which teachers are comfortable with the use of technology as an educational device (Brevik et al. 2019; Uerz et al. 2018). In other words, developing pre-service teacher digital competence in TEP can be seen as process where TEP enables pre-service teacher to think, interact and implement technological knowledge into future educational practices (Eraut 2010).

This characterisation aligns with the Mishra and Koehler (2006) Technological-Pedagogical-Content-Knowledge (TPACK) framework. It identifies multiple intersections between the core knowledge domains that inform teachers’ ways of teaching: content, pedagogy and technology. TPAK is then defined as “an emergent form of knowledge that goes beyond all three components (content, pedagogy, and technology)” (Mishra and Koehler 2006, p. 1028).

The TPACK framework maps a dynamic process wherein pre-service teachers begin by constructing their knowledge in a teacher education institution. However, teacher education institutions often struggle to develop the rich learning environment required to bring together pre-service teachers’ technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge in this way even though integrating these knowledge domains can help pre-service teachers to understand why digital technologies are important and when and how they can best be integrated into early childhood educational practice (Bakir 2015; Koehler et al. 2014; Player-Koro 2013). Pre-service teachers’ digital competences are best supported when “the content is part of a context that the students can perceive as meaningful, assign value to the subject matter, and develop an understanding of the relation of it with their lives” (Mishra and Koehler 2006: 1034). The knowledge domains of the TPACK framework, therefore, can provide a rich description of the ways teacher education institutions might develop pre-service teacher’s digital competences.

3 Method

This study examines whether or not early childhood education pre-service teachers are prepared to use ICT in their future educational practices and how this process is conducted in TEP. This study was carried out on pre-service teachers in the final year of their 3.5-year long TEP. Four focus group discussions with pre-service teachers and five interviews with teacher educators were carried out.

Focus group studies are frequently used in educational research to collect data relating to a group’s or an individual’s experiences and understandings of a specific topic (Puchta and Potter 2004). They also offer a powerful way of encouraging members of such groups to interact in open and in-depth discussions about the addressed topic (Creswell 2012). Out of the 80 pre-service teachers who were invited to take part in the study, 25 of them volunteered to participate in a semi-structured focus group discussion. The participants had completed all of their taught courses and were working on their undergraduate dissertations. Four focus group discussions were organised: two focus groups consisting of five and seven pre-service teachers respectively in September 2017 and two focus groups with four and nine pre-service teachers respectively in September 2018. In order to reflect potential differences between study mode, students studying on campus and at a distance in both years were included in each focus group.

The focus group discussions were moderated by the researcher and were between 40 to 65 min long. By asking questions, and involving all the participants, the researcher tried to challenge focus group members to share their understandings, experiences and stories of ICT use.

The discussions were guided by seven key questions. The questions focused on the rationale for ICT and the extent to which it had been integrated into teacher education, how pre-service teachers perceived their digital competences, what they found useful and how they proposed to use ICT in their future work as preschool teachers. Other questions related to what they found helpful, what possible challenges and gaps were, as well as ideas for improvement.

Then, in order to contextualize and deepen the analysis of the focus group interviews, five semi-structured interviews were performed with their teacher educators in late 2018 using the same interview questions and guidelines as those used for the focus groups. The interviews and focus group discussions were tape recorded after obtaining informed consent from the participants.

3.1 Data analysis

The collected data were transcribed verbatim into nine (four focus group discussions and five interviews) separate documents. Initially, each of the transcribed documents was read on multiple occasions to identify meaning units. These were the different patterns of reasoning about how the pre-service teachers are prepared during their TEP to use digital technologies in early childhood education. Then the meaning units were inductively coded (Guest et al. 2012). All of the codes were sequenced and no meaning units were left out or used multiple times. The codes were then reviewed and refined and similar codes were grouped together under broad themes. Examples from the recorded interviews and focus group discussions were also extracted to exemplify the themes that emerged.

The interviews and focus group were conducted in Swedish and selected excerpts translated into English by the researcher. The Swedish ethical regulations for research (The Swedish Research Council 2017) were taken into account when conducting this study. The pre-service teachers and teacher educators were given clear information about their participation in the study as well as the terms and conditions for their contribution to it. It was also made clear that the collected empirical data would be used only for academic purposes and that participants’ identities would be protected.

4 Findings

4.1 Pre-service teachers’ perceived digital competences

The pre-service teachers in the focus groups argued passionately for the necessity and importance of developing preschool teachers’ digital competences. They said that digital technologies are an important part of life and education and referred to the Swedish preschool curriculum to make their point. They felt that digital technologies needed to be integrated throughout their TEP. They suggested that preschool teachers’ competence in using digital technologies in preschool could minimise the digital divide and reduce digital inequality amongst young children.

Accordingly, they argued that mastering ICT could contribute to pre-service teachers’ comfort and confident use of digital technologies in preschool educational practices. Their own understanding of digital competences varied from using digital artefacts, such as tablets, computer teaching and documentation and showing animated films, to computer programming (or coding) and choosing the most suitable tools and resources for children’s development. However, a majority of the participating pre-service teachers indicated that they did not feel well prepared to use ICT in a real preschool setting. One focus group participant commented:

I haven’t acquired very many digital competences from the programme. (Jasmin, Focus Group (hereafter FG) 1, 2017)

Another remarked:

I believe that the teacher education programme has not contributed very much to the development of my digital competences. (Camilla, FG 4, 2018)

In similar vein, some of the pre-service teachers commented that their preschool TEP did not provide enough opportunities for them to develop their digital competences and noted that they were eager to deepen their knowledge and skills. Said one:

… to be honest, I don’t have very much experience of digital tools. I don’t feel that I have acquired the necessary skills to use ICT in preschool educational practices in my teacher education either, but I am eager to learn. (Josefine, FG 4, 2018)

In addition, the participants noted that they used a variety of digital tools and applications in their daily life, including Word, PowerPoint and social media applications such as Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat, thus indicating that they had learned these skills on their own, mostly by trial and error. However, they specifically mentioned that being able to use these digital tools/applications was not enough to integrate ICT into preschool educational practices.

I can use a variety of applications such as Word, Excel and PowerPoint, but I am not sure if I can use ICT in preschool educational practices. (Emily, FG 2, 2017)

Another pre-service teacher specifically remarked that:

… we have no idea how tablets can be used to structure preschool activities ... or how we can choose appropriate applications. (David, FG 1, 2017)

These findings suggest that the pre-service teachers in this study had concerns about their ability to use ICT in early childhood education because of the quality of the technology integration in their TEP. These pre-service teachers particularly wanted to develop their technological skills in way that enabled them to use digital technologies effectively in their preschool educational practices.

4.2 Preparing pre-service teachers’ to use digital technologies

All of the pre-service teachers who took part in this study mentioned the importance of providing ICT-infused learning activities during their TEP. The focus group members particularly addressed a few ICT-related initiatives and learning opportunities that they were given throughout their TEP that were designed to develop their digital competences. As the following discussion shows, ICT-related activities did not feature in every course, nor do they seem to have featured prominently.

-

We had nothing [no ICT-related activities] in the first and second terms, in the third term we had some [parts] in art education. What else did we have? Oh yes, we also had some [ICT-related activities] in terms four and six!

-

Well, we had ... yes it was with computers, yes in the third term.

-

No, it was in the fourth term ... and then we had a little bit.

-

Yes, it was the fourth term and then we had some time in term six as well. (Juila, Nina and Allis, FG 3, 2018)

Other students also commented on the frequency and nature of the ICT-related activities they had encountered on their TEP courses:

… we focused on using ICT twice, including a lecture about the interactive whiteboard and in the art education course on designing, editing and making slow-motion pictures. (Gustave, FG 2, 2017)

In the last course we had language and maths. Information technologies are included in [the courses] language and maths. But in our previous courses we didn’t have such practices. (Josefine, FG 4, 2018)

We had a lecture about programming with BlueBots [programmable floor robot], maybe for one hour, … but those activities were not compulsory. (Maria, FG 4, 2018)

Some of the focus group members talked more positively about the opportunities they had while on their field placements to observe how preschool teachers used ICT in their educational activities. For instance, when acknowledging her supervisor’s digital competences, one of the pre-service teachers said that

my supervisor was used to working with some applications she thought could contribute to children’s learning and development. Once, when I was in the teachers’ planning meeting, they discussed the ways in which an application could be selected. (Monica, FG 2, 2017)

Other pre-service teachers similarly commented that:

To be honest, my last field placement was more creative. My supervisor was responsible for ICT issues in the preschool; thus, I got a lot of great ideas [about how ICT could be used in preschools]. (Elina, FG 2, 2017)

I was lucky to do my field placement with a supervisor who was an ICT teacher, that is, responsible for ICT issues in the preschool. She had started to do programming and I think that is something that is missing. (Nik, FG 3, 2018)

However, several of the pre-service teachers said that their field placement supervisors did not use ICT in their educational practices, which meant that they did not get as much out of their field placements as they had hoped in terms of developing their digital competences. One student remarked:

In the preschool in which I did my field placement, ICT was only used as a documentation tool. (Tina, FG 1, 2017)

Another pre-service teacher commented that:

… in my field placement the school may have worked with ICT in some lessons, but I didn’t see too much of it during my time there. (Gustave, FG 2, 2017)

Ensuring working with and access to practical demonstrations of the ways in which digital technologies can be used in early childhood education does not seem to have been a requirement for pre-service teachers’ field placements. As a result, the chances of locating pre-service teachers with digitally competent supervisors was highly unpredictable.

The teacher educators interviewed in this study, further, stressed the importance of developing early childhood pre-service teachers’ digital competences. They felt this was an essential aspect of their early childhood teacher education programme and emphasized “it is what we try to achieve” (Teacher Educator 3, hereafter TE). The educators understood that the integration of digital technologies into teacher education programmes was one of the educational goals addressed in the Swedish national curriculum for early childhood (2018). According to the curriculum, they were required to “make visible and integrate ICT in the TEP’s syllabus” (TE-1, 2018) and, as a result, the educators claimed, “pre-service teachers’ digital competences are addressed in number of courses” (TE-2, 2018).

The teacher educators studied here felt they paid sufficient attention to the preparation of pre-service teachers to use digital technologies in their future practices in early childhood education. One of the teacher educators said that:

There are a number of the course-specific goals in our TEP which are focused on using ICT…. For instance, in the courses provided in the early semesters, you can find course-specific goals which are focused on developing pre-service teachers’ digital competences including a course about documentation where they are prepared to collect, analyse and report children’s development using digital technologies. In another course about the aesthetic learning process in the third semester, the pre-service teachers are expected to design and develop an educational film/animation using iMovie or another application. Then, in the following semesters, we have learning goals and practices that focus on developing pre-service teachers’ digital competences…. Further, we provide a number of optional workshops about using digital technologies based on the pre-service teachers’ needs and interests (TE-3, 2018).

The teacher educators argued that they used digital technologies in their teaching practices. Referring to the technological infrastructure as in digital learning lab, for example, teacher educators illustrated some of the specific initiatives they were taking to prepare pre-service teachers to use digital technologies in their future educational practices. The ICT vision and polices of the university where this programme was based provided the basis for these initiatives. For instance, the teacher educators mentioned that they were using Learning Management System (LMS), educational films, and desktop presentation software to teach, communicate and share teaching materials with students. One of the teacher educators stated that:

through using the technologies ourselves, we try to exemplify how teaching in early child education can be facilitated by using technologies…. In a course about literacy and mathematics in early childhood education, there are educational practices that demonstrate how technologies can be integrated into the teaching of mathematics in early childhood education (TE-4, 2018).

By using such initiatives, teacher educators suggested that they were making visible to students how subject knowledge using digital technologies could be taught in preschools.

When reflecting on how digital technologies were embedded in their TEP, the teacher educators stated that there was no compulsory course specifically about digital technologies in early childhood education and, thus, that there were few assignments that centred on using digital technologies in educational practices. In the same vein, TE-1 (2018) pointed out that in their previous teacher education programme, there had been specific course/s aiming to enhance teacher students’ digital competences. She suggested that there was no reason why similar optional course/s could not be run in the present curriculum, alongside other activities.

It was assumed that digital competences would be embedded in all of the modules and the educational activities that went with them. TE5, for example, argued that every module on a TEP should have a concrete strategy to promote teacher students’ digital competences, not just the TEP as a whole. It may be that the integration of digital technologies into a TEP mostly depends on the individual teacher educators’ way of running a course.

In terms of teacher educators’ TPACK, the interviewed teacher educators acknowledged that some of their colleagues might not themselves have adequate digital competences and admitted that some of their colleagues see the use of digital technologies in early education as pure destruction. However, all of the interviewees explicitly stated that developing pre-service teacher digital competences should be and was a priority. They were conscious that there were challenges to this process which should be embraced and complications which they needed to try to overcome.

4.3 Preparing pre-service teachers to use digital technologies: Challenges and ways forward

The pre-service teachers and teacher educators in this study were both asked to identify what they thought were some of the challenges facing the further implementation of digital technologies in TEPs and how pre-service teachers might be better prepared to use these resources in their future preschool practice.

4.3.1 Introducing “basic” technology courses as part of the teacher education programme

A number of the pre-service teachers indicated that providing a standalone course - or at least a significant part of a course - on digital technology as part of the preschool education programme would give students a broader understanding of digital technologies and the ways in which it could be used in early childhood education practices.

It would be great if we could have a basic course that provided a deep and broad understanding of information technologies in the preschool. Such knowledge could then be developed and integrated into other courses and into subjects such as language, maths etc. (Emily, FG 2, 2017)

One of the participants (Allis, FG 3, 2018) acknowledged that the focus of such an introductory course should not only be on ICT in general, but on the specific use of these technologies in preschool practices.

I think it is important to have some kind of course, such as a 3 ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) or something like that. Many of the [teacher-education] students are really uncertain about [what ICT is and how it could be used]. (Johanna, FG 3, 2018).

Some of the focus group members also suggested that introducing pre-service teachers to the reference literature on ICT in preschool and encouraging them to use it, through, for example, linked assessments, could help them to actively pursue ways of developing their skills.

Teacher educators, although they endorsed the importance of providing an introductory course or part of the course about digital technology in early childhood TEPs, however, argued that

… providing a single course may not solve the problem; students should have opportunities and time to design and practice using technologies (TE-2, 2018).

They made the pedagogical point that learning about a specific technology or application may not actually change pre-service teachers practices nor enable them to integrate these technologies in their future practices.

4.3.2 Integrating digital technologies throughout the TEP

Both teacher educators and pre-service teachers highlighted the suggestion that digital technologies should be integrated across the TEP. TE-4 argued that there was no well-defined guideline about the extent to which digital technologies should be integrated in the early childhood TEP. He suggested that teacher educators could “map a ladder of digital competences that describes the process of a pre-service teacher’s digital competence development”. Pre-service teachers made a number of practical suggestions that would increase the number of opportunities they had during their TEP to design and use digital technologies. As the participants in FG4 pointed out:

-

The use of digital technologies should be embedded in the courses, rather than just being regarded as a technological tool. ICT should be seen and acted on as a common principle/value etc.

-

It should be part of the fabric and that we use it in the same way as we use the curriculum.

-

Part of the fabric, yes.

-

Integrated… (Josefine, Camilla, Maria, and Jenifer, FG 4, 2018)

The participants particularly underlined that by integrating digital technologies in this way, pre-service teachers would be able to build up their confidence in using ICT.

4.3.3 Providing examples of best practices

Both TEs and pre-service teachers pointed out the importance of developing and providing concrete and handy examples to demonstrate how digital technologies could be used in early childhood education and what a challenge this might be. The pre-service teachers indicated that they did not have much practical experience with using digital technologies in preschools.

We need to have first-hand experiences of and opportunities to use information technologies in the TEP. (Elina, FG 2, 2017)

[We really need] more practical experiences.... I enjoy the courses when we are doing practical things, instead of just reading, I think that doing things is fun (Mary, FG 1, 2017).

Another pre-service teacher addressing this challenge, suggested that

It [developing teacher-education students’ digital competences] shouldn’t be about creating a PowerPoint presentation... but about how these tools [ICT] can be used in the preschool. (Nina, FG 3, 2018).

Teacher educators agreed that the pre-service teacher should be given more practice-based teaching and learning opportunities. They specifically suggested that more concrete examples of how digital technologies could be used in the preschool, such as developing books, creating animated films and documenting early childhood education practices would help pre-service teachers to visualise and develop their own ideas. Providing such best practice, as TE-4 expressed it, however depends on local technological support.

4.3.4 Initiating more compulsory teaching and learning opportunities

In Swedish higher education, students’ participation in teaching activities, such as lectures, is not compulsory; it is only a requirement to take part in those educational activities that are examined and graded, such as attending seminars and submitting assessable work. Non-participation in non-compulsory parts of a course can therefore have an impact on pre-service teachers’ competences and digital competences. Providing more (non-compulsory) opportunities to learn about digital technologies would likely not ensure that students would engage with the subject more. As the participants in one focus group pointed out, many pre-service teachers did not take part in activities that were not considered part of their course assessment:

-

… one of the concerns is that some students do not take part in the teaching activities. Only a few students attend some seminars …

-

Those that are compulsory?

-

Perhaps the teacher needs to make their teaching activities more attractive and fun …

-

There might be other motives ...

-

For instance, a large number of students didn’t attend a lecture about programming [coding], because it wasn’t compulsory …

-

I think it is due to a lack of commitment, it is not only the case in digital technology activities, but in the whole of our programme too. It is sad to see, some pay for the education and take out a loan and then do not use the education [to develop their competences beyond the bare requirements]. (David, Maria, Camilla, and Josefine, FG 4, 2018)

This group argued for greater compulsion and increasing the number of graded parts in each course so that all pre-service teachers are encouraged to actively engage in essential training. As another pre-service teacher put it, “for students like me who are not interested in or use information technologies all that much, I really need a push that helps me to explore how and where I can use information technologies (Jasmin, FG 1, 2017).”

4.3.5 Promoting teacher educators’ technological-pedagogical knowledge

The teacher educators’ technological-pedagogical knowledge and skills was another issue that was underlined by both the teacher educators’ and pre-service teachers’ comments alike. TE-2 (2018) asserted that

a number of the teacher educators seem … don’t feel the confidence to teach or model ICT integration in their teaching practices.

TE-4 (2018) explained that “when I have no idea about what and how digital applications in preschool, such as Unikum [an educational management tool] can be used, how I can exemplify the potential of the technologies? … I never got the opportunity to develop my digital skills”. Similarly, TE-3 stated that “we simply cannot make the time [to develop our digital skills], we have a lot to do”.

It is consistent with the pre-service teachers’ observations that some of the TEs did not appear to have the knowledge and skills needed to effectively integrate digital technology into their teaching. One of the participants (FG 4, 2018) noted that in some of teaching situations they had experienced, the students had to help the teacher educators to use the digital technologies. Another remarked:

[The teacher educators] should know how to use ICT and be trained in it, so that they know how it can be used in their own courses. (Josefine, FG 4, 2018)

The teacher educators were themselves aware that they needed, as a profession, more opportunities to develop develop their technological-pedagogical skills so that ICT could be more effectively integrated into their educational practices.

5 Discussion

This study aims to expand and deepen our understanding of the ways early childhood pre-service teachers are prepared to use digital technologies in their future practices. Although numerous studies examine pre-service teachers’ digital preparedness, most of them are based on pre-service teachers’ perspectives. By examining the early childhood pre-service teachers and their teacher educators’ understandings and experiences side by side, this study makes a new contribution to this knowledge field.

The findings of this study suggest that pre-service teachers and teacher educators alike believe passionately in the necessity and importance of developing preschool teachers’ digital competences. However, pre-service teachers feel that during their TEP they are not adequately prepared to integrate ICT into their future educational practices in preschool. The evidence from their focus group discussions suggests that they were given relatively few opportunities to develop their digital competences throughout their TEP.

The evidence from the teacher educators, on the other hand, paints a completely different picture. The teacher educators interviewed here highlighted a variety of initiatives that they were providing to prepare the next generation of preschool teachers to use digital technologies. For example, they cited a workshop they had run on the learning software BlueBots and the initiatives they had taken on number of courses, such as “literacy and mathematics in early childhood education”, “aesthetic learning processes” and “pedagogical documentation” where technology had been integrated across various subject domains in order to support pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge.

The question, thus, is why pre-service teachers, unlike teacher educators, feel they are not being adequately prepared to use digital technologies in early childhood education. This could be understood in different ways.

-

1)

The TEP does provide a sufficient learning experience, but the students.

-

A)

do not attend and are not engaged in the scheduled teaching events because they are not compulsory.

-

B)

do not fully understand what is taught during the TEP. The results show that the pre-service teachers seemed not to recognise the number of opportunities to “meet” ICT in the TEP that the teacher educators say exists for them. Such encounters could be made much more visible and consciously examined. Enabling pre-service teachers to see the ways their learning contributes to their TPACK knowledge and skills can give them the confidence that they do have sufficient training and are able to use digital technologies in supportive and pedagogical ways. Creating such educational opportunities can offer further valuable intersections for pre-service teachers to make connections between what they learned in their TEP and the reality of using technologies in an actual preschool environment (Admiraal et al. 2017; Røkenes and Krumsvik 2016).

-

C)

have in fact learned a great deal but still do not feel comfortable using these technologies looking forward. Developing early childhood pre-service teachers’ TPACK is a complex process involving various factors that eventually informs not only the pre-service teachers’ understandings, values and skills but their actual use of digital technologies in preschool. The pre-service teachers may actually have the knowledge and skills they require to integrate digital technologies into their educational practices, but this “does not necessarily lead a teacher to believe in the value of the technology for her teaching practices” (Blackwell et al. 2013, p. 311).

-

A)

-

2)

It is not possible for pre-service teachers to become fully comfortable with digital technologies and how to teach them at the TEP stage, because they have reached the extent of what it is possible to learn in a TEP and only at the next level of learning, the contextualised learning that takes place in-situ, will their understanding develop further.

-

3)

The TEP does not provide a sufficient learning environment to develop teacher students’ TPACK at the same time as developing pre-service teachers’ TPACK is not firmly anchored in TEP. Teacher educators have a dual responsibility in this regard. Not only should they integrate digital technologies into their own practices and act as role models for pre-service teachers, but they also need to maintain, if not grow, their professional digital competence so that they can effectually communicate this competence (TPACK) to the next generation of early childhood teachers. According to the data collected here, the expertise of teacher educators and mentors varies considerably; some do not appear to have the necessary technological, pedagogical and content knowledge to form a technology-rich learning environment. Despite having access to a range of technologies and approaches, a number of teacher educators were reported as not being able to make full use of digital technologies because of a lack of time, technological support or simply because they were not confident in using these technologies themselves. This suggests that it is important to provide more in-service education, technological support, time and resources to integrate technologies into the teacher educator’s educational activities.

The general consensus from the research reviews (cf. Bakir 2015; Blackwell et al. 2013; Instefjord and Munthe 2017; Nikolopoulou and Gialamas 2015; Voogt and McKenney 2017) suggests that developing pre-service teachers’ digital competences can be shaped by the teacher educators’ values and their technological-pedagogical skills, the nature of the institution they attend, the infrastructure of their preschool field placement (such as the availability of technologies and software on site), the technological and pedagogical support they receive while in training, as well as the models or strategies that the TEP uses to prepare pre-service teachers to integrate digital technologies into their future practices.

The data collected as part of this study suggests that the pre-service teachers were all familiar with and used a range of technological artefacts, including social media, MS Office and learning management systems (LMS) in their everyday lives. It may be significant that the new generation of pre-service teachers are increasingly developing their technological knowledge (TK), but their technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPK) still needs to be strengthened. Drawing on previous studies (Enochsson, 2010), this study highlights the point that being familiar with and using digital technologies does not automatically enable pre-service teachers to take advantage of them in the preschool setting. However, past mastery experiences with TK and a positive perception of the usefulness of digital technologies can contribute to their greater use in early childhood education (Nikolopoulou and Gialamas 2015).

In addition, the pre-service teachers appreciated field placement experiences where they had the opportunity to realise and make use of the ICT they had encountered on their TEP. Endeavouring to secure placement environments where digital technologies were routinely put in place could be a potential solution to the problems students face when moving from theory to practice. These findings are supported by Lim (2012) and Kay (2007) who indicate the importance of problematising and modelling the use of ICT in preschools for student teachers. Providing practical field experiences in preschools that are linked to their coursework can enhance their effective use of ICT as trained professionals. Pairing up pre-service preschool teachers with digitally competent field placement supervisors who know how to integrate ICT in their educational practices is a challenging process. The preschools in which pre-service teachers do their fieldwork may not have access to the necessary digital technologies. The pre-service teachers mentioned that providing a stand-alone course - or at least part of a course - on ICT might give them a better picture of why, what and how technologies can be integrated into early childhood educational practices. This would no doubt be helpful but it would likely not be sufficient to allow pre-service teachers to use digital technologies in pedagogically meaningful ways in preschools (cf. Bakir 2015; Kay 2007). Developing a more integrated and connected experience could help future early childhood teachers to integrate technologies into early childhood education.

6 Conclusion

Policymakers, national curriculums, and other actors place particular importance on developing pre-service teachers’ digital competences as the means to develop young children’s capacity to engage with the digital world. By addressing how well pre-service teachers are prepared to integrate ICT into early childhood education, the study draws attention to a more pervasive problem by suggesting that developing pre-service teachers’ digital competence is more than just the acquisition of a particular set of linked skills.

The evidence gathered here shows that pre-service teachers and teacher educators have had rather different understanding about how pre-service preschool teachers’ digital competences are developed during TEP. The pre-service teachers think they are not adequately prepared enough, while the TEs think they are providing a variety of educational opportunities to develop pre-service teachers TPACK. This issue can be more challenging when current teacher educators are also struggling to develop their competence in a constantly changing yet newly compulsory area of content in the early childhood education teaching programme. This study, accordingly, supports the provision of more support to help teacher educators/mentors and pre-service teachers explore the interface between TPACK and early years educational practices.

Data availability

All collected data are available.

References

Admiraal, W., van Vugt, F., Kranenburg, F., Koster, B., Smit, B., Weijers, S., & Lockhorst, D. (2017). Preparing pre-service teachers to integrate technology into K–12 instruction: Evaluation of a technology-infused approach. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 26(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2016.1163283.

Bakir, N. (2015). An exploration of contemporary realities of technology and teacher education: Lessons learned. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 31(3), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2015.1040930.

Blackwell, C. K., Lauricella, A. R., Wartella, E., Robb, M., & Schomburg, R. (2013). Adoption and use of technology in early education: The interplay of extrinsic barriers and teacher attitudes. Computers and Education., 69, 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.07.024.

Brevik, L. M., Gudmundsdottir, G. B., Lund, A., & Stromme, T. A. (2019). Transformative agency in teacher education: Fostering professional digital competence. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86(102875), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.005.

Brown, C. P., Englehardt, J., & Mathers, H. (2016). Examining preservice teachers' conceptual and practical understandings of adopting iPads into their teaching of young children. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.018.

Buss, R. R., Wetzel, K., Foulger, T. S., & Lindsey, L. (2015). Preparing teachers to integrate technology into K–12 instruction: Comparing a stand-alone technology course with a technology-infused approach. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 31(4), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2015.1055012.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Cuban, L. (2001). Oversold and underused : Computers in the classroom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cuban, L. (2018). The flight of a butterfly or the path of a bullet? : Using technology to transform teaching and learning. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Davis, N. (2010). Technology in preservice teacher education. In P. Penelope, B. Eva, E. B. B. McGaw, P. Peterson, & M. Barry (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (Third ed., pp. 217–221). Oxford: Elsevier.

Enochsson, A.-B. (2010). ICT in initial teacher training: Swedish report. Retrieved from Paris: OECD.

Eraut, M. (2010). Knowledge, working practices, and learning. In S. Billett (Ed.), Learning through practice: Models, traditions, orientations and approaches (pp. 37–58). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Farmer, L. (2016). Incorporating information literacy into instructional design within pre-service teacher programs. In Information Resources Management Association (Ed.), Professional development and workplace learning : Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications. Hershey: Business Science Reference, An Imprint of IGI Global.

Government Bill. (2009). Regeringens proposition 2009/10:89: Bäst i klassen – en ny lärarutbildning Stockholm: (in Swedish).

Government Bill. (2017). Stärkt digital kompetens i skolans styrdokument. Stockholm: (in Swedish).

Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2018). Newly qualified teachers’ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 214–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1416085.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Data reduction techniques. In G. Guest, K. M. MacQueen, & E. E. Namey (Eds.), Applied thematic analysis (pp. 129–159). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Hu, X., & Yelland, N. (2017). An investigation of preservice early childhood teachers’ adoption of ICT in a teaching practicum context in Hong Kong. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 38(3), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2017.1335664.

Instefjord, E. J., & Munthe, E. (2017). Educating digitally competent teachers: A study of integration of professional digital competence in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.016.

Kay, R. H. (2007). A formative analysis of how preservice teachers learn to use technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 23(5), 366–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00222.x.

Kerckaert, S., Vanderlinde, R., & van Braak, J. (2015). The role of ICT in early childhood education: Scale development and research on ICT use and influencing factors. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 23(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2015.1016804.

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Kereluik, K., Shin, T. S., & Graham, C. R. (2014). The technological pedagogical content knowledge framework. In M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. J. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 101–112). New York: Springer.

Krumsvik, R. J. (2011). Digital competence in Norwegian teacher education and schools. Högre Utbildning, 1(1), 39–51.

Lim, E. M. (2012). Patterns of kindergarten children’s social interaction with peers in the computer area. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(3), 399–421.

Lindahl, M. G., & Folkesson, A.-M. (2012). ICT in preschool: Friend or foe? The significance of norms in a changing practice. International Journal of Early Years Education, 20(4), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2012.743876.

Marklund, L. (2015). Preschool teachers’ informal online professional development in relation to educational use of tablets in Swedish preschools. Professional Development in Education, 41(2), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.999380.

Masoumi, D. (2015). Preschool teachers use of ICTs: Towards a typology of practice. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood (CIEC), 16(1), 5–17.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Nikolopoulou, K., & Gialamas, V. (2015). Barriers to the integration of computers in early childhood settings: Teachers’ perceptions. Education and Information Technologies., 20, 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-013-9281-9.

Player-Koro, C. (2013). Hype, hope and ICT in teacher education: A Bernsteinian perspective. Learning, Media and Technology, 38(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2011.637503.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice. London: SAGE.

Røkenes, F. M., & Krumsvik, R. J. (2016). Prepared to teach ESL with ICT? A study of digital competence in Norwegian teacher education. Computers & Education, 97, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.02.014.

Scherer, R., Tondeur, J., Siddiq, F., & Baran, E. (2018). The importance of attitudes toward technology for pre-service teachers’ technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge: Comparing structural equation modeling approaches. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.003.

The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2018). Curriculum for the preschool- Lpfö 18. Stockholm: Skolverket.

The Swedish Research Council. (2017). God forskningssed. Vetenskapsrådets rapportserie, 1. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Tømte, C., Enochsson, A.-B., Buskqvist, U., & Kårstein, A. (2015). Educating online student teachers to master professional digital competence: The TPACK-framework goes online. Computers & Education, 84, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.01.005.

Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., Sang, G., Voogt, J., Fisser, P., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2012). Preparing pre-service teachers to integrate technology in education: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Computers & Education, 59(1), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.009.

Uerz, D., Volman, M., & Kral, M. (2018). Teacher educators’ competences in fostering student teachers’ proficiency in teaching and learning with technology: An overview of relevant research literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 70, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.005.

UNESCO. (2011). UNESCO ICT competency framework for teachers. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000213475.

Voogt, J., & McKenney, S. (2017). TPACK in teacher education: Are we preparing teachers to use technology for early literacy? AU - Voogt, joke. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 26(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2016.1174730.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Prof. Göran Fransson for his contributions and encouragement in the development of this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gävle. The author wishes to thank the University of Gävle, Sweden, that funded the present study (Net-based learning project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest.

Code availability

Custom code.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masoumi, D. Situating ICT in early childhood teacher education. Educ Inf Technol 26, 3009–3026 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10399-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10399-7