Abstract

Background and Aims

Gastritis is a common histological diagnosis, although the prevalence is decreasing in developed populations, alongside decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection. We sought to determine the prevalence of the etiology of gastritis in a Swedish population sample and to analyze any associations with symptoms, an area of clinical uncertainty.

Methods

Longitudinal population-based study based in Östhammar, Sweden. A randomly sampled adult population completed a validated gastrointestinal symptom questionnaire (Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire, ASQ) in 2011 (N = 1175). Participants < 80 years of age and who were eligible were invited to undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) (N = 947); 402 accepted and 368 underwent EGD with antral and body biopsies (average 54.1 years, range 20–79 years; 47.8% male) with H. pylori serology.

Results

Gastritis was found in 40.2% (148/368; 95% CI 35.2–45.2%). By rank, the most common histological subtype was reactive (68/148; 45.9%), then H. pylori (44/148; 29.7%), chronic non-H. pylori (29/148; 19.6%), and autoimmune (4/148; 2.7%). Gastritis was significantly associated with older age and H. pylori status (p < 0.01). Gastritis subjects were divided into three histological categories: chronic inactive inflammation, autoimmune gastritis, and active inflammation; there was no difference in the presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms when categories were compared to cases with no pathological changes. Functional dyspepsia or gastroesophageal reflux were reported in 25.7% (38/148) of those with gastritis (any type or location) versus 34.1% (75/220) with no pathological changes (p = 0.32). Epigastric pain was more common in chronic H. pylori negative gastritis in the gastric body (OR = 3.22, 95% CI 1.08–9.62).

Conclusion

Gastritis is common in the population with a prevalence of 40% and is usually asymptomatic. Chronic body gastritis may be associated with epigastric pain, but independent validation is required to confirm these findings. Clinicians should not generally ascribe symptoms to histological gastritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Histological gastritis is a common condition and not always due to Helicobacter pylori infection [1]. Data from developed populations indicates the prevalence of gastritis has declined in recent decades [2]. This is likely explained by the decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection, shown in Europe, Asia, and US [3,4,5,6]. Studies performed in individuals with and without symptoms undergoing elective esophago-gastroduodenoscopy (EGD) report varying rates of gastritis, from 37% to 57% [7,8,9]. While there has been increased recognition of non-H. pylori gastritis, its clinical significance in many cases is not well defined.

There is an established link between H. pylori and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) [10]. However, the relationship with gastroduodenal symptoms is unclear; in outpatient studies H. pylori positive and negative patients with functional dyspepsia had similar symptom profiles [9,10,11]. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are frequent patient complaints seen by physicians [12], yet, few have an established organic cause for their symptoms. While “endoscopic gastritis” may incorrectly be ascribed to epigastric symptoms by clinicians, histological gastritis is generally considered incidental [13].

There are limited current data regarding gastric histology prevalence in the general population and in asymptomatic individuals [3, 9, 14,15,16]. Of the data available, there is not a clear relationship between symptoms and endoscopic findings [9, 14, 15]. However, as most studies in the literature have not been truly population-based with a comprehensive evaluation of the histology, and with H. pylori gastritis now less common, an association between various forms of histological gastritis and symptoms may have been missed. Determining which histological lesions have clinical significance has implications for both practice and management.

We aimed to determine if histological gastritis, including active inflammation (neutrophils) or inactive (chronic) inflammation (lymphocytes, plasma cells), is associated with GI symptoms in a general population. We randomly selected subjects in Östhammar, Sweden and offered an upper endoscopy regardless of symptom status. The sample obtained was representative of the Swedish population [3], so this study represents a unique opportunity to analyze the prevalence of all forms of histological gastritis in a general population, to describe the characteristics of gastritis and to evaluate the relationship of gastric histology with symptoms.

Methods

This study was performed from LongGerd, a longitudinal population-based study of GI symptoms with an EGD performed in 2011/2012; the full details of the study have been presented previously [3, 17, 18]. A validated questionnaire on abdominal and GI symptoms, the Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire (ASQ) [3, 19], was mailed in 1988, 1989, 1995, and 2011 to all adults in Östhammar, Sweden born on day 3, 12, or 24 of each month, a sampling procedure equivalent to random sampling allowing the same participants to be followed over time. In addition, serology and endoscopy results were available for a subset of the 2011/2012 cohort, which are analyzed here.

Setting

2011/2012 Study

In December 2010, Östhammar had 21,373 inhabitants, of whom 92% were Swedish citizens. The distribution of inhabitants living in either urban/rural areas, age, gender, family size, income, and occupation was similar to the national average. The level of education was slightly better than the average.

Procedures

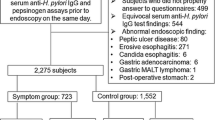

The sampling procedure for the 2011 mail survey and 2012 EGD study is shown in Fig. 1. From a final study population of 1924, 1073 individuals responded to the ASQ and were between 20 and 80 years of age; of these 402 were available and agreed to participate in the EGD study regardless of symptom status, and overall, 368 biopsy-sets of antrum and corpus were available for analysis.

Sampling procedure 2011 mail survey and 2012 population-based endoscopy study. The final study population (n = 1924) was higher than the ASQ mail survey population (n = 1645) because all participants in previous surveys were invited as well even if they had moved from Östhammar. Note all comers were invited for endoscopy. The details of sample selection have been published in detail previously (reference 3). ASQ—Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire. EGD—esophagogastroduodenoscopy

As previously described [3], 688 non-responders were significantly younger, but there were no major differences in the groups otherwise, indicating non-response bias appears to be minimal in the 2011 mail survey and the study cohort is likely representative of the Swedish general population.

Five experienced endoscopists participated. A consensus meeting led by an external expert (Dr. Lars Lundell) reviewed multiple video recordings per the study protocol prior to commencement. Each endoscopist was monitored on the first day by the project leader (LA). The endoscopists were unaware of medical/symptom history and H. pylori status.

Variables

Symptoms

Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (GERS) and functional dyspepsia (FD) were defined based on the ASQ [19], which asks if the participant has experienced the symptom during the last 3 months. GERS was defined as being bothered by heartburn and/or acid regurgitation in the past 3 months with daily or weekly symptoms [20]. FD was defined as the presence of postprandial distress syndrome (PDS)—postprandial fullness and/or early satiety; or epigastric pain syndrome (EPS)—presence of pain or discomfort in the epigastric region only (not relieved by defecation), consistent with the Rome III criteria [21].

Medications

After the EGD findings were recorded and locked, a complete medical history including all medication use was recorded.

H. pylori Serology

Blood samples were taken immediately prior to EGD for a specific enzyme immunoassay (GastroPanel, Biohit PLC, Helsinki, Finland).

Gastric Biopsies

Two biopsies were taken from both the antrum and corpus for haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Warthin Starry (WS) staining and assessed according to the widely used and well accepted Sydney System [22] by three experienced pathologists (MV, LV, and MW). Any discrepancies in gastritis classification between the expert pathology observers was resolved by discussion when double reading the section. The pathologists were blinded to all patient and endoscopic data.

H. pylori gastritis was detected by H&E and WS stain.

Autoimmune gastritis was diagnosed by corpus atrophy with intestinal metaplasia and hyperplasia of endocrine-like cells [23]. Autoantibodies were not measured. Reactive gastropathy was defined by foveolar hyperplasia, prominence of smooth muscle fibers as well as vasodilatation, together with chronic inflammation [22].

Classification of Status of Gastric Mucosa

The findings of gastritis were grouped a priori based on the presence of active inflammation (neutrophils) or inactive (chronic) inflammation (lymphocytes, plasma cells). The categories were: chronic inactive (Group 1—chemical reactive gastritis or chronic not active gastritis), autoimmune gastritis (Group 2), and active with neutrophils (Group 3 –H. pylori gastritis, lymphocytic gastritis). Subjects with no pathological changes served as the comparison group.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA (version 15.1, StataCorp, Texas, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using multiple logistic regression adjusted for age and gender unless otherwise specified. A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to the multiple hypothesis tests reported, p < 0.05 should be considered suggestive of an association rather than definitive and be interpreted in combination with the effect size (odds ratio).

Results

The study group comprised 368 subjects (192 women; 52.2%), with a mean age of 54.1 years (SD 13.2; range 20–79 years).

Gastritis (any type or location) was present in 40.2% (148/368). Antral gastritis was present in 40% (147/368) and body gastritis in 20.4% (75/368). 74 subjects had gastritis in both antrum and corpus, 73 in antrum only, and one in the corpus only (Table 1).

Reactive gastritis was the most common subtype (45.9%, 68/148), followed by H. pylori (29.7%, 44/148) and chronic non-H. pylori gastritis (19.6%, 29/148). Reactive gastritis was restricted to the antrum (69/69), while chronic and H. pylori gastritis mainly affected both antrum and corpus (42/44 and 22/29, respectively).

Twelve subjects had evidence of atrophy—six affecting antrum only, three in corpus only, and three at both sites. Of these, four had autoimmune gastritis, five H. pylori gastritis, and the remaining three had chronic not active gastritis.

Histopathological examination revealed no pathological changes in the corpus and antrum in 59.8% (220/368) (see Table 2).

H. pylori Status and Status of Gastric Mucosa

56/368 subjects (15.2%) had positive serology for H. pylori, of which 47/56 (83.9%) had histological gastritis (OR 9.58, 95% CI 4.47–20.56), mainly H. pylori (42/56) followed by chronic gastritis (3/56).

Forty Four subjects were diagnosed with H. pylori gastritis by H&E, of which three had a negative WS stain and two had negative serology. This was attributed to suppression of the bacteria or possible patchy distribution throughout the stomach. All subjects with reactive gastritis had a negative WS stain and negative H. pylori serology. All subjects with inactive corpus gastritis were negative for H. pylori by histology, however, three subjects had positive serology (probably ex-H. pylori gastritis).

Factors Associated with Gastritis

Age

Compared to subjects with no pathological changes, subjects with gastritis were older: mean age 57.5 years (range 24–79 years; SD 11.9) versus 52.0 years (range 20–78 years; SD 13.6); p = 0.001, Mann–Whitney), notably those with H. pylori gastritis (mean age 60.5 years, SD 11.5; range 29–78). Gastritis prevalence increased with age (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.05) (Fig. 1).

Sex

There was no gender difference in the distribution of histological gastritis; 74/192 (38.5%) of women had gastritis and 74/176 (42.0%) of men (p = 0.47, logistic regression).

Medications

Consumption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (45/368, 12.2%) was not associated with gastritis in either the antrum (OR = 1.54, 95% CI 0.80–2.94) or corpus (OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.39–2.31). Similarly, proton pump inhibitors (PPI) (34/368, 9.2%) were not associated with antral (OR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.45–1.96) or corpus gastritis (OR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.26–1.61).

The presence of other medications potentially contributing to GI symptoms was minimal—four subjects had antibiotics in the previous 3 months, two were taking anti-epileptics, one was taking carbidopa/levodopa, and one subject was taking loperamide.

Association of Status of Gastric Mucosa with Symptoms

Upper GI symptoms (FD or GERS) were reported in 30.7% (113/368); 25.7% (38/148) of those with gastritis (any type or location) reported upper GI symptoms, compared with 34.1% (75/220) of subjects with no pathological changes (p = 0.32).

Gastritis (any type or location) was found in 35.2% (38/108) of subjects with FD, compared with 42.8% of those without FD (112/262) (p = 0.57). Gastritis was found in 31.8% (7/22) of those with GERS, compared with 40.8% of those without GERS (141/346) (p = 0.54). Overall, rates of gastritis were similar with and without symptoms.

In total 34.1% (15/44) of subjects with H. pylori gastritis reported symptoms, compared with 38.3% of those without (124/324) (p = 0.75). Most subjects with atrophy were asymptomatic (75%; 9/12).

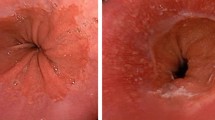

Chronic inactive corpus gastritis was associated with a greater than threefold likelihood of epigastric pain (OR 3.22, 95% CI 1.08–9.62), compared to no pathological changes (Fig. 2, Table 3). Of those with chronic inactive corpus gastritis, only one subject was taking NSAIDs (1/23; 4.3%).

Autoimmune or active gastritis in the corpus, or gastritis of any type in the antrum was not associated with the presence or absence of FD or GERS (Table 3).

Discussion

In our population-based study of 368 individuals with and without symptoms with antral and corpus biopsies taken at EGD, histological gastritis was detected in 40%. The majority of individuals had no histopathological changes, whether symptoms were present or not. Epigastric pain was associated with inactive corpus gastritis with an over three-fold increased risk. Otherwise, we found no clear association between the histological status of the gastric mucosa and the presence of upper GI symptoms.

The overall prevalence of gastritis in our study is consistent with other reports [7,8,9]. However, the proportion of gastritis subtypes varies between studies. We found the most common gastritis subtypes were reactive, H. pylori and chronic non-H. pylori, affecting 19% (68/368), 12% (44/368), and 8% (29/368), respectively. Proportions were slightly higher, but comparable to Wolf et al. [7] where reactive gastropathy was the most common (21%), followed by ex-H. pylori (19%) and H. pylori gastritis (19%). Similarly, a US study of 895,323 individuals who underwent EGD [24] observed H. pylori-associated chronic active gastritis in 22% and reactive gastropathy in 18%. In contrast, Nordenstedt [8] found H. pylori gastritis was more frequent (32%) than non-H. pylori gastritis (8%), likely driven by the population prevalence of H. pylori.

The declining prevalence of gastritis in developed populations [2] is consistent with a decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection [3,4,5,6]. In turn, there has been increased recognition of non-H. pylori gastritis, though its significance is not well defined. Evidence suggests non-H. pylori gastritis is more commonly isolated to one part of the stomach compared to H. pylori gastritis [25]. This was congruent with our findings; reactive gastritis was always found in the antrum, while H. pylori gastritis almost always affected both antrum and corpus. Interestingly, reactive gastritis is negatively correlated with H. pylori [26], emphasizing that reactive gastritis is distinct from H. pylori gastritis. This was reflected in our study, where all subjects with reactive gastritis had negative H. pylori serology. The exact pathophysiology remains unclear.

In our study, 84% of subjects seropositive for H. pylori (15%) had gastritis. All subjects with reactive gastritis were seronegative for H. pylori, while subjects with chronic gastritis negative for bacteria in the antrum and corpus were seropositive in 18% and 13%, respectively, suggestive of ex-H. pylori gastritis. It is known serology cannot differentiate between active and prior infection [27] as anti-H. pylori antibodies can persist after eradication. Thus a combination of at least two diagnostic tests is recommended for diagnosis [27]. In a Swedish population study of 1000 subjects who underwent EGD and H. pylori serology conducted over 20 years ago, 43% were positive for H. pylori, 34% had signs of current infection on histology or culture, and 9% were seropositive with otherwise negative testing [28]. Comparatively, our rate of H.pylori seropositivity was lower at 15%, and 4% were seropositive without histological evidence of H. pylori.

Consistent with the literature, age was associated with increasing gastritis prevalence, with no difference between the sexes. Others [24] found over a lifetime the gastric mucosa became abnormal in 50% of subjects. While we found no sex difference with gastritis overall, there were slightly more men with H. pylori gastritis (58%). The greater likelihood for men to be infected with H. pylori has been demonstrated previously though how sex may affect the acquisition and/or persistence of H. pylori infection is not fully understood [29].

Our results did not support an association between PPIs and gastritis, though this may have been influenced by the low number of cases taking PPIs. Most subjects taking PPIs had no histopathological changes, despite PPI-induced hypertrophy of parietal cells, and the most common gastritis subtypes were reactive (12/27) followed by H. pylori (8/27). PPI use may promote the diagnosis of H. pylori negative gastritis, by masking H. pylori infection [30]. In Nordenstedt’s study [8], PPI or H2 inhibitor use was more common in subjects with H. pylori negative gastritis. Muszynski et al. [25] found subjects with H. pylori gastritis were taking PPIs less often, though this was not significant. Contrastingly, Nasser et al. [30] reported previous PPI exposure decreased the likelihood of H. pylori (OR = 0.22; 95% CI 0.12–0.39).

NSAID use has been linked to reactive gastritis, mainly affecting the antrum [31]. We found of subjects taking NSAIDs who had gastritis, reactive gastritis was the most common (15/21) and affected the antrum only in 14 of 15 cases, however, this was not statistically significant.

In our study, upper GI symptoms were reported in 30.7% (113/368) of subjects (FD 29.2%; GERS 6.0%). Notably, histological gastritis was not associated with functional dyspepsia or gastroesophageal reflux, and numerically gastritis was less likely to be found in these disorders. Though there was no association between most symptoms and gastritis, epigastric pain was associated with chronic H. pylori negative gastritis in the corpus. However, this result needs to be interpreted with caution because of multiple comparison testing despite the large odds ratio over 3 (with wide confidence limits), and may reflect a type I error.

While the potential sequelae of H. pylori infection are known, acute infection is often asymptomatic, and most patients with chronic active infection remain asymptomatic probably for life [32]. Additionally, patients with peptic ulcer disease often have atypical symptoms, or can be asymptomatic [33]. Multiple groups have reported a lack of association between symptoms and histology [9, 14, 15, 26]. For example, Wolf et al. [26] found epigastric symptoms were present in 31.6% of individuals with reactive gastritis, compared with 21.9% in those without. Similarly, 25.7% of our subjects with gastritis reported upper GI symptoms, compared with 34.1% in those without any pathological changes. In a population study of 501 subjects who underwent EGD, Borch et al. [14] found no difference in the frequency of digestive symptoms.

There is evidence that non-ulcer patients with epigastric pain show more benefit from H. pylori eradication than patients with postprandial distress (76% vs. 46%) [34]. While acute inflammation resolves completely after eradication, chronic inflammation is slow to resolve and can be present for up to 12 years [35]. It was not known in our study which subjects had previous eradication therapy. It is possible the presence of chronic corpus gastritis and epigastric pain is related to distant prior H. pylori infection, as 13% (3/23) were seropositive for H. pylori. Regardless, the results suggest chronic gastritis in the corpus may sometimes be associated with epigastric pain. If there is a true association, whether gastric acid secretion is the underlying mechanism remains uncertain, but acid blockers significantly improve epigastric pain in those with dyspepsia who have no peptic ulcer [36]. It is also worthwhile noting the number of subjects diagnosed with autoimmune gastritis in this study was small, therefore limiting any conclusions. For instance, Carabotti et al. [37] reported patients with autoimmune gastritis may experience a number of dyspeptic symptoms, mostly postprandial distress.

Overall, the apparent lack of association between GI symptoms and gastritis poses the question: where are symptoms arising if the stomach is normal? Postprandial distress syndrome (early satiety and/or postprandial fullness) has been linked to increased and degranulating duodenal eosinophils [38, 39], suggesting low-grade inflammation and immune activation may generate symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Duodenal biopsies were not analyzed in this study; however, this would be of interest in future studies.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several strengths including being population-based and applying a validated symptom assessment approach. The subjects were representative of the general population and selection bias is unlikely [3]. While some subjects with upper GI symptoms may have sought help and received treatment, the number taking medications potentially affecting GI symptoms was minimal. We did not have details regarding previous H. pylori eradication, possibly explaining the discrepancy between H. pylori serology and positive histology in a minority. The study sample was very well characterized and true population-based endoscopic studies are rare emphasising the relatively unique nature of the data presented. Gastritis is largely asymptomatic according to the present results and clinicians should not ascribe symptoms to the histologic finding. Although the odds ratio was large (over 3-fold increased), because of multiple comparison testing the finding that epigastric pain syndrome was more common in chronic H. pylori negative gastritis in the gastric body needs independent verification. Whether the study findings can be generalized beyond Sweden is also uncertain.

Conclusion

In this population-based study of 368 individuals with or without symptoms who underwent EGD, we found a gastritis prevalence of 40%, and the most common type was reactive gastritis. The prevalence of H. pylori gastritis in this study is consistent with the downward trend of infection in developed countries. Increasing age was significantly associated with gastritis, however, sex and use of PPIs or NSAIDs were not. While upper GI symptoms were reported in 35% of individuals, histologic gastritis should generally not be ascribed to upper GI symptoms.

References

Odze R, Goldblum J. Inflammatory disorders of the stomach. In: 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009; 285.

Sipponen P, Maaroos HI. Chronic gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:657–667.

Agréus L, Hellström PM, Talley NJ, Wallner B, Forsberg A, Vieth M et al. Towards a healthy stomach? Helicobacter pylori prevalence has dramatically decreased over 23 years in adults in a Swedish community. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:686–696.

Kumagai T, Malaty HM, Graham DY, Hosogaya S, Misawa K, Furihata K et al. Acquisition versus loss of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: results from an 8-year birth cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:717–721.

Ciociola AA, McSorley DJ, Turner K, Sykes D, Palmer JBD. Helicobacter pylori infection rates in duodenal ulcer patients in the United States may be lower than previously estimated. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1834–1840.

Asfeldt AM, Steigen SE, Løchen ML, Straume B, Johnsen R, Bernersen B et al. The natural course of Helicobacter pylori infection on endoscopic findings in a population during 17 years of follow-up: the Sørreisa gastrointestinal disorder study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:649–658.

Wolf EM, Plieschnegger W, Geppert M, Wigginghaus B, Höss GM, Eherer A et al. Changing prevalence patterns in endoscopic and histological diagnosis of gastritis? Data from a cross-sectional Central European multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:412–418.

Nordenstedt H, Graham DY, Kramer JR, Rugge M, Verstovsek G, Fitzgerald S et al. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastritis: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:65–71.

Dooley CP, Cohen H, Fitzgibbons PL, Bauer M, Appleman MD, Perez-Perez GI et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1562–1566.

Talley NJ. Helicobacter pylori and dyspepsia. Yale J Biol Med. 1999;72:145–151.

Veldhuyzen Van Zanten S. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:63–9.

Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1259–1268.

Tytgat GNJ. Role of endoscopy and biopsy in the work up of dyspepsia. Gut. 2002;50:13–16.

Borch K, Jõnsson KÅ, Petersson F, Redéen S, Mårdh S, Franzén LE. Prevalence of gastroduodenitis and Helicobacter priori infection in a general population sample: relations to symptomatology and life-style. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1322–1329.

Johnsen R, Bernersen B, Straume B, Forde OH, Bostad L, Burhol PG. Prevalences of endoscopic and histological findings in subjects with and without dyspepsia. Br Med J. 1991;302:749–752.

Agréus L, Engstrand L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity among Swedish adults with and without abdominal symptoms: a population-based epidemiologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:752–757.

Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671–680.

Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Talley NJ, Jones MP, Tibblin G. Natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional abdominal disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2905–2914.

Agreus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Reproducibility and validity of a postal questionnaire: the abdominal symptom study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1993;11:252–262.

Vakil N, Van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus CME. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920.

Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380–1392.

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated sydney system. International workshop on the histopathology of gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–81.

Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis-pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:529–41.

Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Changes in the gastric mucosa with aging. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2276–2281.

Muszyński J, Ziółkowski B, Kotarski P, Niegowski A, Górnicka B, Bogdańska M et al. Gastritis—facts and doubts. Prz Gastroenterol. 2016;11:286–295.

Wolf EM, Plieschnegger W, Schmack B, Bordel H, Höfler B, Eherer A et al. Evolving patterns in the diagnosis of reactive gastropathy: data from a prospective Central European multicenter study with proposal of a new histologic scoring system. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:847–854.

Lopes AI, Vale FF, Oleastro M. Helicobacter pylori infection—recent developments in diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9299–9313.

Storskrubb T, Aro P, Ronkainen J, Vieth M, Stolte M, Wreiber K et al. A negative Helicobacter pylori serology test is more reliable for exclusion of premalignant gastric conditions than a negative test for current H. pylori infection: a report on histology and H. pylori detection in the general adult population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:302–11.

Ibrahim A, Morais S, Ferro A, Lunet N, Peleteiro B. Sex-differences in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatric and adult populations: systematic review and meta-analysis of 244 studies. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:742–749.

Nasser SC, Slim M, Nassif JG, Nasser SM. Influence of proton pump inhibitors on gastritis diagnosis and pathologic gastric changes. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4599–4606.

Carpenter HA, Talley NJ. Gastroscopy is incomplete without biopsy: clinical relevance of distinguishing gastropathy from gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:917–924.

Katelaris P, Hunt R, Bazzoli F, Cohen H, Fock KM, Gemilyan M, Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, Piscoya A, Quach D, Vakil N, Vaz Coelho LG, LeMair A, Melberg J. Helicobacter pylori world gastroenterology organization global guideline. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57:111–126.

Aro P, Storskrubb T, Ronkainen J, Bolling-Sternevald E, Engstrand L, Vieth M et al. Peptic ulcer disease in a general adult population: the Kalixanda study: a random population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1025–1034.

Lan L, Yu J, Chen YL, Zhong YL, Zhang H, Jia CH et al. Symptom-based tendencies of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3242–3247.

Mera R, Fontham ETH, Bravo LE, Bravo JC, Piazuelo MB, Camargo MC et al. Long term follow up of patients treated for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 2005;54:1536–1540.

Ford A, Mahadeva S, Carbone F, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia. The Lancet 2020;396:1689–1702.

Carabotti M, Lahner E, Esposito G, Sacchi MC, Severi C, Annibale B. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in autoimmune gastritis a cross-sectional study. Med (United States). 2017;96:15784.

Talley NJ, Walker MM, Aro P, Ronkainen J, Storskrubb T, Hindley LA et al. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: an adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1175–1183.

Shah A, Fairlie T, Brown G, Jones MP, Eslick GD, Duncanson K, Thapar N, Keely S, Koloski N, Shahi M, Walker MM, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Duodenal eosinophils and mast cells in functional dyspepsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2229–2242.e29.

Funding

The study was supported by Olympus (Box 1816, 171 23 Solna, Sweden), who supplied study equipment. This research received no other specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Nicholas J. Talley reports non financial support from Norgine (2021) (IBS interest group), personal fees from Allakos (gastric eosinophilic disease) (2021), Bayer [IBS] (2020), Planet Innovation (Gas capsule IBS) (2020), twoXAR Viscera Labs, (USA 2021) (IBS-diarrhoea), Dr Falk Pharma (2020) (EoE), Sanofi-aventis, Glutagen (2020) (Celiac disease), IsoThrive (2021) (oesophageal microbiome), BluMaiden (microbiome advisory board) (2021), Rose Pharma (IBS) (2021), Intrinsic Medicine (2022) (human milk oligosaccharide), Comvita Mānuka Honey (2021) (digestive health), Astra Zeneca (2022), outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Talley has a patent Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) 1998, Biomarkers of IBS licensed, a patent Licensing Questionnaires Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire licensed to Mayo/Talley, a patent Nestec European Patent licensed, and a patent Singapore Provisional Patent “Microbiota Modulation Of BDNF Tissue Repair Pathway” issued, “Diagnostic marker for functional gastrointestinal disorders” Australian Provisional Patent Application 2021901692. Committees: OzSage, Australian Medical Council (AMC) [Council Member]; Australian Telehealth Integration Programme; NHMRC Principal Committee (Research Committee) Asia Pacific Association of Medical Journal Editors, Rome V Working Team Member (Gastroduodenal Committee), International Plausibility Project Co-Chair (Rome Foundation funded), COVID-19 vaccine forum member (by invitation only). Community group: Advisory Board, IFFGD (International Foundation for Functional GI Disorders), AusEE. Editorial: Medical Journal of Australia (Editor in Chief), Up to Date (Section Editor), Precision and Future Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, South Korea, Med (Journal of Cell Press). Dr. Talley is supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to the Centre for Research Excellence in Digestive Health and he holds an NHMRC Investigator grant.

Ethical approval

LongGERD 2010/443 Regional Ethics Board in Uppsala.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A concise commentary on this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08171-1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuzek, R., Potter, M., Talley, N.J. et al. Prevalence of Histological Gastritis in a Community Population and Association with Epigastric Pain. Dig Dis Sci 69, 528–537 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08170-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-023-08170-2