Abstract

Background

The optimal antibiotic therapy duration for cholangitis is unclear. Guideline recommendations vary between 4 and 14 days after biliary drainage. Clinical observations and some evidence however suggest that shorter antibiotic therapy may be sufficient.

Objective

To compare the effectiveness and safety of short-course therapy of ≤ 3 days with long-course therapy of ≥ 4 days after biliary drainage in cholangitis patients.

Methods

We searched the databases PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and trial registers for literature up to August 5, 2020. RCTs and observational studies including case series reporting on antibiotic therapy duration for acute cholangitis were eligible for inclusion. Two reviewers independently evaluated study eligibility, extracted data, assessed risk of bias and quality of evidence. A meta-analysis was planned if the included studies were comparable with regard to important study characteristics. Primary outcomes included recurrent cholangitis, subsequent other infection, and mortality.

Results

We included eight studies with 938 cholangitis patients. Four observational studies enrolled patients treated for ≤ 3 days. Recurrent cholangitis occurred in 0–26.8% of patients treated with short-course therapy, which did not differ from long-course therapy (range 0–21.1%). Subsequent other infection and mortality rates were also comparable. Quality of available evidence was very low.

Conclusion

There is no high-quality evidence available to draw a strong conclusion, but heterogeneous observational studies suggest that antibiotic therapy of ≤ 3 days is sufficient in cholangitis patients with common bile duct stones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute cholangitis is a life-threatening infection which is managed with adequate source control (biliary drainage) and antibiotic therapy (ABT) [1, 2]. The optimal ABT duration for cholangitis is unclear. The Tokyo Guidelines (TG) 2018 recommend 4 to 7 days of ABT for cholangitis after biliary drainage [3]. If a bacteremia with gram-positive cocci is present, this guideline recommends a minimum duration of 14 days. The Dutch national sepsis guideline recommends a maximum of 3 days of ABT for cholangitis after biliary drainage [4]. Similarly, the optimal ABT duration for complicated intra-abdominal infections has been debated. A RCT and two post-hoc analyses showed that 4 days of ABT resulted in similar outcomes when compared with longer duration in patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections (of which 10.8% suffered from biliary tree infection) [5,6,7]. As a result, the revised Surgical Infection Society guidelines recommend to limit ABT to 4 days after source control [8], and the World Society of Emergency Surgery guidelines suggest a short course of 3–5 days for complicated intra-abdominal infections [9]. In contrast, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines are more conservative and recommend ABT for 7–10 days for most serious infections and sepsis [10].

Clinicians hesitate to shorten ABT because consensus and harmonized guidelines are lacking for cholangitis, which leads to a wide variety of ABT duration based on personal preference instead of evidence [11]. Additionally, we assume they fear recurrent infections or insufficient treatment of cholangitis complicated by bacteremia. But recurrent infections are often due to inadequate biliary drainage and may not be preventable with longer ABT [5]. While prolonged ABT does increase the risk of side-effects, mortality and antimicrobial resistance, and causes an extra financial burden on the healthcare system [12,13,14,15,16].

So far, one systematic review on this topic has been published by Tinusz et al.[17] In their review, four studies were included with a total of 205 cholangitis patients, and short-course ABT was defined as a shorter ABT duration than suggested by the available guidelines, which resulted in a diversified short-course therapy (SCT) group ranging from 3 to 14 days. In our opinion, it was necessary to reexamine the effectiveness and safety of a real short-course ABT (SCT of ≤ 3 days) versus long-course therapy (LCT) of ≥ 4 days after biliary drainage in cholangitis patients, and considering that new studies have emerged.

Methods

We registered the protocol of this systematic review on PROSPERO (CRD42020175393). We reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) Statement [18].

Eligibility Criteria

We considered RCTs and observational studies including case series eligible for inclusion. Case reports (less than five cases), conference abstracts, and reviews were excluded. Studies written in English were eligible if they reported on patients with acute cholangitis who received biliary drainage, in which duration of ABT was reported, and with a follow-up of at least 30 days. Primary outcomes—as defined by the authors of individual studies—were recurrent cholangitis, subsequent other intra-abdominal or extra-abdominal infection, and mortality. Secondary outcomes included ABT duration, total length of hospital stay, adequacy of empirical therapy (empirical ABT covered the causative organisms found in a blood culture), subsequent infection with highly resistant micro-organisms (HRMO), and Clostridioides difficile infection.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

A clinical librarian searched the electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library up to 5 August 2020, using a combination of text words and controlled vocabulary. Two reviewers (S.H. and M.W.) checked the trial registers ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN registry, EU Clinical Trials Register and WHO ICTRP for ongoing/unpublished trials and scanned reference lists of included studies. The search strategies are shown in Appendix 1 in Supplementary Materials.

Study Selection, Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (S.H. and M.W.) independently evaluated study eligibility, extracted data, assessed risk of bias and quality of evidence. Disagreements were solved by consensus. Authors of ongoing trials were contacted and asked for the availability of data. We extracted the following data: publication details, study design, eligibility criteria, patient characteristics, sample size, details of the intervention, outcome measures and follow-up duration. We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool version 2, the ROBINS-I tool and the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessment of risk of bias (at outcome level) in randomized studies, observational intervention studies, and the observational single-arm study, respectively.[19,20,21] A score of 8–9 stars in the NOS was considered as low risk of bias, 6–7 stars as moderate, and 0–5 stars as high. We rated the quality of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Statistical Analysis

We aimed to compare SCT with LCT, with SCT defined as ≤ 3 days and LCT as ≥ 4 days. In case these data could not be extracted, we planned to compare SCT and LCT as defined by the authors of individual studies. We planned to summarize the data descriptively. We also planned to provide summary measures (risk ratios for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes) and to perform a meta-analysis if the included studies were comparable with regard to important study characteristics.

Results

Study Selection

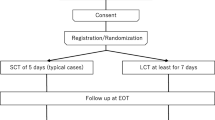

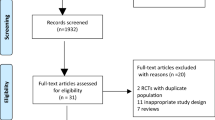

The electronic database search yielded 2439 records, and 8 records were identified from trial registers. After removal of duplicates, 1766 records were screened for relevance. Three eligible ongoing studies were identified of which the data was not yet available [22,23,24]. We retrieved 41 full-text articles, of which eight met all inclusion criteria (Fig. 1) [11, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Study Characteristics

The study characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. Two RCTs were included, one prospective single-arm study, and five retrospective studies with a total of 938 patients. In five out of eight studies, acute cholangitis was defined according to the diagnostic criteria of the TG. More than 80% of patients suffered from cholangitis due to common bile duct stones (CBDS). Patients with different etiologies were enrolled in 5 out of 8 studies [25, 26, 28,29,30]. Haal et al. and Satake et al. compared SCT (≤ 3 days) with LCT (≥ 4 days) [11, 31]. In the single-arm study of Kogure et al. ABT was stopped after temperature was < 37 °C for 24 h.[26] Van Lent et al. compared SCT (≤ 3 days) with medium-course therapy (MCT; 4/5 days) and LCT (> 5 days) [30]. The short ABT-regimens in the remaining studies were longer than 3 days and were considered LCT in this review. The short ABT group of Doi et al. was treated for ≤ 7 days [25], and of Netinatsunton et al. until temperature was below 38 °C for 72 h.[27] Park et al. assigned patients to early oral antibiotic switch or to conventional intravenous (IV) regime, but all patients received ABT for 14 days [28]. Uno et al. compared patients treated before May 2013 (ABT: 14 days) and after May 2013 (ABT < 14 days) [29]. All patients received empirical ABT intravenously. Some patients switched to oral ABT after initial recovery. Types of ABT prescribed were penicillins, a combination of a penicillin with a aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone, cephalosporins, a combination of a cephalosporin with a aminoglycoside or metronidazole, a fluoroquinolone or a carbapenem. The ERCP was performed as soon as possible in the study of Kogure et al.[26] In the other studies, the time between admission and the ERCP ranged from within 24 h, [11, 25, 27,28,29] to a maximum of 4.5 days [30, 31]. The timing of the drainage differed significantly between the study groups in the studies of Haal et al., Satake et al., and Doi et al. [11, 25, 31]. Follow-up duration ranged between 4 weeks and 6 months.

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Table 2a–c shows the results of the risk of bias assessments. All studies had methodological limitations. The two RCTs were at low risk of bias in three out of five domains, while two out of five domains raised some concerns [27, 28]. We considered the observational intervention study of Doi et al. to be at moderate risk of bias [25], and the four other observational intervention studies to be at serious risk of bias, especially due to a high risk of confounding [11, 29,30,31]. We judged the prospective single-arm study of Kogure et al. to be at moderate risk of bias [26].

Quality of Evidence

The quality of evidence was very low for all outcomes. Main reasons for down rating the evidence were design limitations of the included studies, indirectness (different study populations, and only a minority of patients treated for ≤ 3 days), and imprecision (only small studies, and few events).

Results of Individual Studies

Tables 3 and 4 show the individual study results regarding primary and secondary outcomes.

Recurrent Cholangitis

All studies assessed recurrent cholangitis. Haal et al. reported recurrence rates of 7.3% and 11.3% in the SCT (≤ 3 days) and LCT groups (≥ 4 days), respectively (p = 0.238) [11]. In the study of Kogure et al., none of the 18 patients developed recurrent cholangitis (median ABT: 3 days) [26]. Satake et al. reported rates of 9.1% and 1.4% in the SCT (≤ 3 days) and LCT groups (≥ 4 days), respectively (p = 0.13) [31]. Van Lent et al. reported rates of 26.8%, 21.1% and 20% in the SCT (≤ 3 days), MCT (4/5 days) and LCT groups (> 5 days), respectively (p = 0.80) [30]. Doi et al. reported rates of 6.5% and 7.9% in patients treated for ≤ 7 days and ≥ 8 days (p = 0.69) [25]. In the study of Netinatsunton et al., recurrent cholangitis did not occur in the fever-based group (mean ABT: 4.6 days), compared to one recurrence (6.3%) in the 14-day group (p = 0.485) [27]. Park et al. reported rates of 3.4% in the early oral switch group, and 0% in the conventional IV group (p = 0.50) [28]. Uno et al. reported four recurrences (13.3%) in the group treated for 14 days (median ABT: 14.5 days), and zero in the group treated for < 14 days (median ABT: 10 days; p = 0.036) [29].

Subsequent Other Intra-abdominal or Extra-abdominal Infection

Three studies assessed this outcome [11, 25, 26]. Haal et al. reported six patients (4.3%) with a local infectious complication in the SCT group, compared with seven patients (4.4%) in the LCT group (p = 0.992) [11]. In the study of Kogure et al. none of the patients developed complications related to cholangitis or needed re-administration of ABT [26]. In the study of Doi et al., four patients (5.6%) treated for ≤ 7 days developed bacteremia, liver abscess or other complications related to cholangitis, compared with 12 patients (9.1%) treated for ≥ 8 days (p = 0.43) [25].

Mortality

Six studies assessed mortality [11, 25, 28,29,30,31]. The studies of Kogure et al. and Netinatsunton et al. did not report mortality as outcome but we assessed rates of 0%, because all patients visited the outpatient clinic or were contacted by telephone [26, 27]. Haal et al. reported mortality rates of 0% and 2.5% in the SCT and LCT groups, respectively (p = 0.13) [11]. Satake et al. reported rates of 0% and 2.7% in the SCT and LCT groups (p = 1) [31]. Van Lent et al. reported rates of 14.6%, 10.5% and 5% in the SCT, MCT and LCT groups (no p value reported) [30]. In the study of Doi et al., mortality rates were 4.7% and 5.7% in patients treated for ≤ 7 days and ≥ 8 days (p = 0.74) [25]. No deaths were observed in the study of Park et al.[28]. Uno et al. reported two deaths (5.7%), and both patients were treated before May 2013 (p = 0.179) [29].

ABT Duration

Five studies reported total ABT duration which are show in Table 4 [24,25,26,27,29]. In these studies, most patients received biliary drainage within 24 h after admission. Haal et al. and Satake et al. reported both total and ABT duration after biliary drainage [11, 31], while van Lent et al. only after biliary drainage (timing unknown) [30].

Total Length of Hospital Stay

Five studies assessed hospital stay [11, 27,28,29, 31]. Haal et al. reported a median hospital stay of 6 days for SCT, and 7 days for LCT (p = 0.03) [11]. Satake et al. reported a mean hospital stay of 19.5 days in the SCT, and 21.3 days in the LCT group (p = 0.73) [31]. In the study of Netinatsunton et al., mean hospital stay did not significantly differ (5.8 days vs 6.4 days; p = 0.467) [27]. Park et al. reported a mean hospital stay of 10.8 days in the early oral switch group and 12.3 days in the conventional IV group (p = 0.02) [28]. Uno et al. reported a median hospital stay of 14 days and 17.5 days in the groups treated after and before May 2013 (p < 0.001) [29].

Adequacy of Empirical Therapy

Two studies assessed adequacy of empirical therapy [25, 29]. Doi et al. reported rates of adequate empirical ABT of 96% and 87% in the groups treated for ≤ 7 days and ≥ 8 days (p = 0.02) [25]. Uno et al. reported rates of 90% and 75% in the groups treated after and before May 2013 (no p-value reported) [29].

Subsequent Infection with HRMO and C. difficile Infection

None of the enrolled patients developed these outcomes, only assessed by Haal et al.[11]

Synthesis of Results: SCT ≤ 3 Days Versus LCT ≥ 4 Days

Four observational studies included a total of 211 patients treated for ≤ 3 days [11, 26, 30, 31]. Recurrent cholangitis occurred in 0 to 26.8% of patients treated with SCT of ≤ 3 days, which did not differ from LCT (range 0–21.1%). Subsequent other infection (range 0–4.3% vs 4.4%-9.1%) and mortality (range 0–14.6% vs 0–10.5%) were also comparable. Secondary outcomes were scarcely reported. Haal et al. reported a median hospital stay of 6 days in patients with SCT of ≤ 3 days [11], while Satake et al. reported a mean stay of 19.5 days [31]. A wide range was found in patients treated for ≥ 4 days (5.8–21.3 days) [11, 27,28,29, 31]. We did not perform a meta-analysis because the included studies were too heterogeneous. The study populations differed significantly in etiology and severity of cholangitis, and number of patients with bacteremia. Moreover, the definition of ABT duration varied from total versus after drainage.

Discussion

The optimal ABT duration for cholangitis after biliary drainage remains arguable, while appropriate ABT use improves patient outcomes and reduces antimicrobial resistance [12,13,14,15,16]. None of the included studies found significant differences in outcomes between SCT and LCT according to their own definition of SCT and LCT. No evidence was available from RCTs on the effectiveness and safety of SCT of ≤ 3 days in cholangitis patients after biliary drainage. Heterogeneous observational studies of low quality suggest that ABT of ≤ 3 days is sufficient in cholangitis patients with CBDS.

ABT plays an important role in the initial treatment of acute cholangitis [2]. In the included studies, blood cultures appeared to be standard care while bile cultures were done infrequently. As advised by the TG18, blood and bile cultures should be routinely performed to guide and further optimise ABT [1]. Evidence in patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections support the opinion that ABT can be stopped quickly after source control is established [5,6,7]. Still, there is a need for well-designed studies which accurately evaluate the effectiveness and safety of SCT ≤ 3 days after biliary drainage in cholangitis patients.

We are looking forward to the results of three ongoing studies [22, 24]. The FANTASTIC trial might end with a SCT group of ≤ 3 days—as they randomly assigned patients to a fever-based group: ABT is stopped when temperature is below 37 °C for 24 h or to a guideline-based group: ABT for 4–7 days [22]. The group of Doi et al. compares ABT of ≥ 5 days with ABT of ≥ 7 days in a RCT [24], while the third study (retrospective case–control) compares ABT of < 7 days with ABT > 7 days in patients with cholangitis admitted to the intensive care [22].

Strengths of this review are that we aimed to minimize bias by performing a thorough search, by working with two independent reviewers, and by our decision not to pool the data. On the other hand, our review has limitations. First, the majority of included studies was observational. Second, we were not able to draw a strong conclusion about the effectiveness and safety of SCT of ≤ 3 days, because only 211 patients were treated for ≤ 3 days. Third, the variance in reporting ABT duration (after and total) and different enrolled study populations withheld us providing summary measures and performing a meta-analysis. At the same time, we were not able to perform a subgroup analysis due to the limited number of patients with other etiologies than CBDS. Hence, the generalizability of our results is limited. Only van Lent et al. included a high number of patients (64%) with complex causes of cholangitis, which are more dependent on the technical success of drainage [30]. This might explains the high rates of recurrent cholangitis and mortality in all treatment groups. Besides the technical success of the ERCP, timing of biliary drainage has also impact on the outcome of acute cholangitis, regardless of ABT duration [32, 33]. In three included studies, the timing of biliary drainage differed significantly between the SCT and LCT groups [11, 26, 31]. However, in the study of Doi et al. both groups underwent biliary drainage within 24 h. While in the two other studies, biliary drainage was performed on a later time point in the SCT group. Hence, it unlikely that the effectiveness and safety of SCT were positively affected by the variance in timing of biliary drainage.

In conclusion, currently, there is no high-quality evidence available to draw a strong conclusion about the optimal ABT duration for cholangitis after biliary drainage. Prospective studies are awaited to confirm the results of observational studies which suggest that ABT of ≤ 3 days is sufficient in cholangitis patients with CBDS.

References

Miura F, Okamoto K, Takada T et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018;25:31–40

van den Hazel SJ, Speelman P, Tytgat GN, Dankert J, van Leeuwen DJ. Role of antibiotics in the treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent cholangitis. Clin Infect Dis 1994;19:279–286

Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2018;25:3–16

Sieswerda E, Bax HI, Hoogerwerf JJ, et al. The Dutch Working Party on Antibiotic Policy (SWAB) guidelines for emperical antibacterial therapy of sepsis in adults. 2020. https://swab.nl/nl/sepsis. Accessed December 2020.

Sawyer RG, Claridge JA, Nathens AB et al. Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1996–2005

Hassinger TE, Guidry CA, Rotstein OD et al. Longer-duration antimicrobial therapy does not prevent treatment failure in high-risk patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017;18:659–663

Rattan R, Allen CJ, Sawyer RG et al. Patients with complicated intra-abdominal infection presenting with sepsis do not require longer duration of antimicrobial therapy. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:440–446

Mazuski JE, Tessier JM, May AK et al. The surgical infection society revised guidelines on the management of intra-abdominal infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2017;18:1–76

Sartelli M, Chichom-Mefire A, Labricciosa FM et al. The management of intra-abdominal infections from a global perspective: 2017 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg 2017;12:29

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:304–377

Haal S, Ten Böhmer B, Balkema S et al. Antimicrobial therapy of 3 days or less is sufficient after successful ERCP for acute cholangitis. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2020;8:481–488

Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, Goossens H, Pringle M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:13

Marston HD, Dixon DM, Knisely JM, Palmore TN, Fauci AS. Antimicrobial resistance. JAMA 2016;316:1193–1204

Riccio LM, Popovsky KA, Hranjec T et al. Association of excessive duration of antibiotic therapy for intra-abdominal infection with subsequent extra-abdominal infection and death: a study of 2,552 consecutive infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014;15:417–424

Sartelli M, Weber DG, Ruppe E et al. Antimicrobials: a global alliance for optimizing their rational use in intra-abdominal infections (AGORA). World J Emerg Surg 2016;11:33

Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1308–1315

Tinusz B, Szapáry L, Paládi B et al. Short-course antibiotic treatment is not inferior to a long-course one in acute cholangitis: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:307–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5327-6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed January 2020.

Ruynosuke H, Yousuke N. Fever-based versus guideline-based antiobiotic therapy for acute cholangitis following successful endoscopic biliary drainage: a multicenter randomized trial (FANTASTIC trial). UMIN000019814. https://rctportal.niph.go.jp/en/detail?trial_id=UMIN000019814. Accessed August 2020.

Garret C. Is short antibiotherapy duration after drainage suitable for patients admitted in the intensive care medicine with a sever acute cholangitis? (CASCAD) NCT04173286. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04173286. Accessed August 2020

Iwata K, Doi A, Oba Y et al. Shortening antibiotic duration in the treatment of acute cholangitis: rationale and study protocol for an open-label randomized controlled trial. Trials 2020;21:97

Doi A, Morimoto T, Iwata K. Shorter duration of antibiotic treatment for acute bacteraemic cholangitis with successful biliary drainage: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24:1184–1189

Kogure H, Tsujino T, Yamamoto K et al. Fever-based antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis following successful endoscopic biliary drainage. J Gastroenterol 2011;46:1411–1417

Netinatsunton N, Limmathurotsakul D, Attasaranya S et al. Short duration versus 14-day antibiotic treatment in acute cholangitis due to bile duct stone: a randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res 2019;8:3020–3024

Park TY, Choi JS, Song TJ et al. Early oral antibiotic switch compared with conventional intravenous antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis with bacteremia. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:2790–2796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-014-3233-0.

Uno S, Hase R, Kobayashi M et al. Short-course antimicrobial treatment for acute cholangitis with Gram-negative bacillary bacteremia. Int J Infect Dis 2017;55:81–85

van Lent AU, Bartelsman JF, Tytgat GN, Speelman P, Prins JM. Duration of antibiotic therapy for cholangitis after successful endoscopic drainage of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:518–522

Satake M, Yamaguchi Y. Three-day antibiotic treatment for acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis with successful biliary duct drainage: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2020;96:343–347

Du L, Cen M, Zheng X et al. Timing of performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and inpatient mortality in acute cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2020;11:e00158

Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L et al. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 2019;51:472–491

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinical librarian F.S. van Etten-Jamaludin for her help with the search strategy.

Funding

The authors did not receive external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haal, S., Wielenga, M.C.B., Fockens, P. et al. Antibiotic Therapy of 3 Days May Be Sufficient After Biliary Drainage for Acute Cholangitis: A Systematic Review. Dig Dis Sci 66, 4128–4139 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06820-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06820-3